eHealth Literacy and Trust in Health Information Sources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Timing

2.2. Study Participants and Sampling

2.3. Sampling Frame and Recruitment

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Data Collection Tool

2.5.1. Demographic Variables

2.5.2. Measuring eHealth Literacy

2.5.3. Identifying the Main Source Used for Health Information

2.5.4. Evaluating the Trust in Health Information Sources

2.6. Statistical Analysis

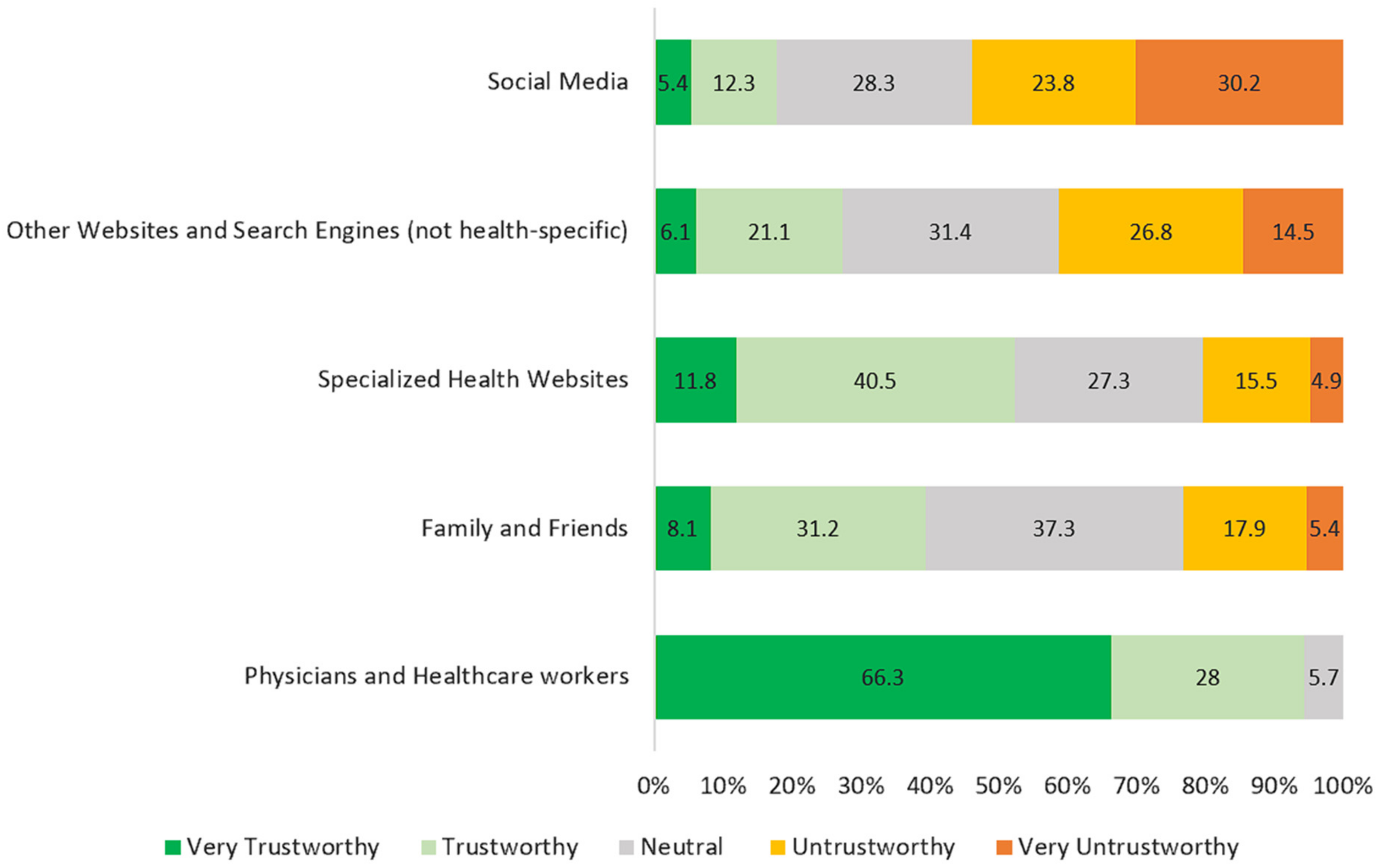

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, X.; Pang, Y.; Liu, L.S. Online Health Information Seeking Behavior: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1740. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alduraywish, S.A.; Altamimi, L.A.; Aldhuwayhi, R.A.; AlZamil, L.R.; Alzeghayer, L.Y.; Alsaleh, F.S.; Aldakheel, F.M.; Tharkar, S. Sources of Health Information and Their Impacts on Medical Knowledge Perception Among the Saudi Arabian Population: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. Orig. Pap. 2020, 22, e14414. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Communications and Information Technology Commission (CITC). “Statistical Yearbook”. Available online: https://www.cst.gov.sa/ar/indicators/PublishingImages/Pages/saudi_internet/saudi-internet-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e27. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Qi, H. A Comprehensive Analysis of E-Health Literacy Research Focuses and Trends. Healthcare 2021, 10, 66. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanti, A.; Chan, D.N.S.; Parut, A.A.; So, W.K.W. Determinants and outcomes of eHealth literacy in healthy adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291229. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brørs, G.; Norman, C.D.; Norekvål, T.M. Accelerated importance of eHealth literacy in the COVID-19 outbreak and beyond. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 458–461. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulec, H.; Kvardova, N.; Šmahel, D. Adolescents’ disease- and fitness-related online health information seeking behaviors: The roles of perceived trust in online health information, eHealth literacy, and parental factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, S.R.; Krieger, J.L.; Stellefson, M.L. The Influence of eHealth Literacy on Perceived Trust in Online Health Communication Channels and Sources. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 53–65. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellefson, M.L.; Shuster, J.J.; Chaney, B.H.; Paige, S.R.; Alber, J.M.; Chaney, J.D.; Sriram, P.S. Web-based Health Information Seeking and eHealth Literacy among Patients Living with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1410–1424. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, E. The Relation Between eHealth Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. Rev. 2023, 25, e40778. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Schulz, P.J.; Chang, A. Addressing the role of eHealth literacy in shaping popular attitudes towards post-COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese adults. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, S.K.; Jungmann, S.M.; Gropalis, M.; Witthöft, M. Conceptualizations of Cyberchondria and Relations to the Anxiety Spectrum: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, F.; Malik, N.I.; Atta, M.; Ullah, I.; Martinotti, G.; Pettorruso, M.; Vellante, F.; Di Giannantonio, M.; De Berardis, D. Relationship between Health-Anxiety and Cyberchondria: Role of Metacognitive Beliefs. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2590. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zayat, A.; Namnkani, S.A.; Alshareef, N.A.; Mustfa, M.M.; Eminaga, N.S.; Algarni, G.A. Cyberchondria and its Association with Smartphone Addiction and Electronic Health Literacy among a Saudi Population. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 162–168. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobryn, M.; Duplaga, M. Does Health Literacy Protect Against Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study? Telemed. E-Health 2024, 30, e1089–e1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yu, X.; Han, C.; Liu, P. Does Internet use aggravate public distrust of doctors? Evid. China Sustain. 2022, 14, 3959. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, E.; Lo, B.; Pollack, L.; Donelan, K.; Catania, J.; Lee, K.; Zapert, K.; Turner, R. The impact of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: National U.S. survey among 1.050 U.S. physicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, e17. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangler, J.; Jansky, M. General practitioners’ challenges and strategies in dealing with Internet-related health anxieties-results of a qualitative study among primary care physicians in Germany. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2020, 170, 329–339. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Qin, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.; Huang, P.; Xie, W. The Effect of Online Health Information Seeking on Physician-Patient Relationships: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. Rev. 2022, 24, e23354. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhuwail, D.; Abdulsalam, Y. Assessing Electronic Health Literacy in the State of Kuwait: Survey of Internet Users from an Arab State. J. Med. Internet Res. Orig. Pap. 2019, 21, e11174. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ruzzieh, M.A.; Al-Helih, Y.M.; Al-Soud, Z. e-Health literacy and online health information utilization among Jordanians: A population-based study. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241288380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhodaib, H. E-health literacy of secondary school students in Saudi Arabia. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 30, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardus, M.; Keriabian, A.; Elbejjani, M.; Al-Hajj, S. Assessing eHealth literacy among internet users in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221119336. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Hero, J.O. Public trust in physicians—U.S. medicine in international perspective. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1570–1572. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, D.J.; Cavanaugh, G.; Thomas-Purcell, K.B.; Caballero, J.; Waldrop, D.; Ayala, V.; Davenport, R.; Ownby, R.L. E-health literacy scale, patient attitudes, medication adherence, and internal locus of control. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2023, 7, e80–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, M.; Brinton, C.; Wiljer, D.; Upshur, R.; Gray, C.S. The impact of eHealth on relationships and trust in primary care: A review of reviews. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Authority of Statistics. Monsha’at Bussiness Atlas. GSATA. Available online: https://atlas.monshaat.gov.sa/ar/profile/region/tabuk (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Wångdahl, J.; Dahlberg, K.; Jaensson, M.; Nilsson, U. Arabic Version of the Electronic Health Literacy Scale in Arabic-Speaking Individuals in Sweden: Prospective Psychometric Evaluation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24466. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J.D.; Dillman, D.A.; Christian, L.M.; Stern, M.J. Comparing check-all and forced-choice question formats in web surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2006, 70, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, P.; Bravo, G.; Poletto, M.; De Odorico, A.; Conte, A.; Brunelli, L.; Arnoldo, L.; Brusaferro, S. Correlation Between eHealth Literacy and Health Literacy Using the eHealth Literacy Scale and Real-Life Experiences in the Health Sector as a Proxy Measure of Functional Health Literacy: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e281. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, V.R.; Majid, S.; Chang, Y.K.; Foo, S. Assessing the influence of health literacy on health information behaviors: A multi-domain skills-based approach. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1038–1045. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsutake, S.; Shibata, A.; Ishii, K.; Oka, K. Associations of eHealth Literacy with Health Behavior Among Adult Internet Users. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e192. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Yu, M.; Yu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Own, C.-M. The Impact of e-Health Literacy on Risk Perception Among University Students. Healthcare 2025, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Biddle, C.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kaphingst, K.; Orom, H. Health Literacy and Use and Trust in Health Information. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 724–734. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Social Media Use for Health Purposes: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17917. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Du, X.; Li, J.; Hou, R.; Sun, J.; Marohabutr, T. Factors influencing digital health literacy among older adults: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1447747. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Tak, S.H. Factors associated with eHealth literacy focusing on digital literacy components: A cross-sectional study of middle-aged adults in South Korea. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221102765. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, K.B.; Tilahun, B.C.; Endehabtu, B.F.; Gullslett, M.K.; Mengiste, S.A. E-health literacy and associated factors among chronic patients in a low-income country: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | n (%) | eHealth Literacy Mean (SD) | Test Statistics | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 407 | 27.17 (5.98) | ||||

| Age | 18–25 | 79 (19.4) | 28.63 (5.99) | r = −0.254 | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 99 (24.3) | 28.39 (5.90) | |||

| 36–45 | 115 (28.3) | 27.57 (4.51) | |||

| 46–55 | 77 (18.9) | 26.01 (5.86) | |||

| 56–65 | 34 (8.4) | 22.11 (7.49) | |||

| >65 | 3 (0.7) | 20.00 (6.93) | |||

| Gender | Male | 220 (54.1) | 26.58 (5.99) | t = −2.160 | 0.031 |

| Female | 187 (45.9) | 27.86 (5.85) | |||

| Education | High School or Below | 68 (16.7) | 25.18 (5.08) | r = 0.234 | <0.001 |

| Diploma | 39 (9.6) | 22.82 (7.71) | |||

| Bachelor’s | 244 (59.9) | 28.06 (5.52) | |||

| Master’s, PhD | 56 (13.8) | 28.71 (5.71) | |||

| Work | Public Sector | 291 (71.5) | 27.18 (5.97) | F (4,402) = 5.51 | <0.001 |

| Private Sector | 25 (6.1) | 28.36 (6.59) | |||

| Student | 46 (11.3) | 28.34 (5.02) | |||

| Retired | 27 (6.6) | 22.56 (6.33) | |||

| Not Working | 18 (4.4) | 29.28 (3.43) | |||

| Chronic Diseases Status | Yes | 106 (26) | 28.42 (6.22) | t = 2.529 | 0.012 |

| No | 301 (74) | 26.73 (5.84) | |||

| Currently on Medications | Yes | 138 (33.9) | 28.37 (6.23) | t = 2.944 | 0.003 |

| No | 269 (66.1) | 26.55 (5.76) | |||

| Not useful at all | Not useful | Unsure | Useful | Very useful | |

| How useful do you find the internet when making decisions about your health? | 36 (8.8%) | 38 (9.3%) | 131 (32.2%) | 175 (43%) | 27 (6.6%) |

| Not important at all | Not important | Unsure | Important | Very important | |

| How important is it for you to be able to access health resources on the internet? | 40 (9.8%) | 31 (7.6%) | 132 (32.4%) | 179 (44%) | 25 (6.1) |

| Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I know what health resources are available on the internet. | 3.23 | 0.97 |

| 2 | I know where to find helpful health resources on the internet. | 3.29 | 1.02 |

| 3 | I know how to find helpful health resources on the internet. | 3.33 | 0.97 |

| 4 | I know how to use the internet to answer my questions about health. | 3.54 | 0.86 |

| 5 | I know how to use the health information I find on the internet to help me. | 3.54 | 0.92 |

| 6 | I have the skills I need to evaluate the health resources I find on the internet. | 3.47 | 0.92 |

| 7 | I can tell high-quality health resources from low-quality health resources on the internet. | 3.60 | 0.83 |

| 8 | I feel confident about using information from the internet to make health decisions. | 2.96 | 1.01 |

| Source | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians and healthcare workers | 206 | 51.9% |

| Family and friends | 32 | 8.1% |

| Specialized health websites (Mayo Clinic, altibbi, etc.) | 61 | 15.4% |

| Other websites and search engines (not health-specific) | 72 | 18.1% |

| Social media (WhatsApp, Instagram, X, etc.) | 26 | 6.5% |

| Health Information Source | B | SE | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians and healthcare workers | 0.864 | 0.460 | 0.061 |

| Family and friends | 0.065 | 0.281 | 0.818 |

| Specialized health websites | 1.845 | 0.321 | <0.001 |

| Other websites and search engines (not health-specific) | 0.291 | 0.055 | 0.241 |

| Social media | −0.641 | 0.238 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhewiti, A. eHealth Literacy and Trust in Health Information Sources. Healthcare 2025, 13, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060616

Alhewiti A. eHealth Literacy and Trust in Health Information Sources. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060616

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhewiti, Abdullah. 2025. "eHealth Literacy and Trust in Health Information Sources" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060616

APA StyleAlhewiti, A. (2025). eHealth Literacy and Trust in Health Information Sources. Healthcare, 13(6), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060616