Ways of Coping with Stress in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Tool

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analyses

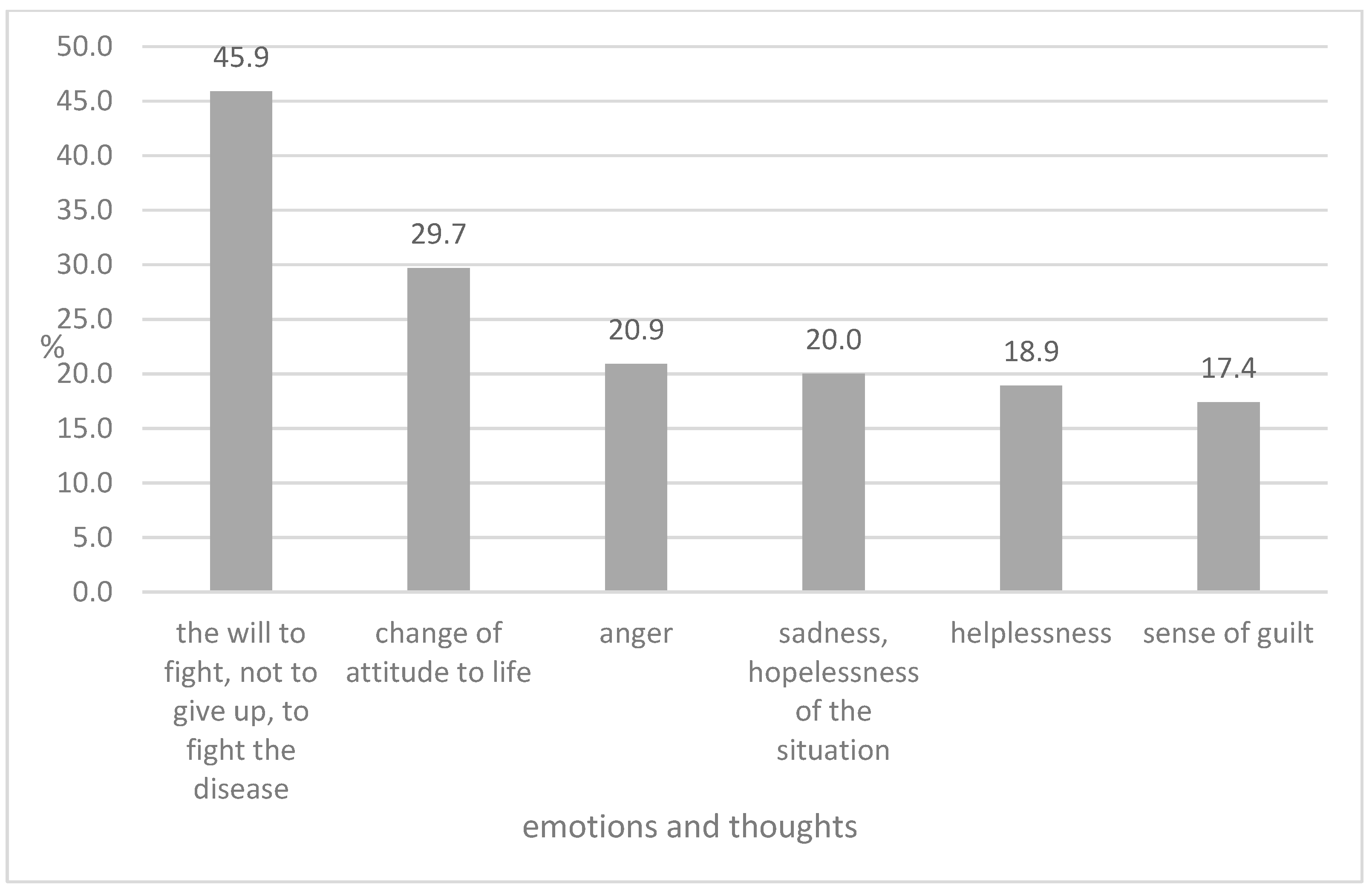

3. Results

3.1. Study Group

3.2. Cancer

3.3. Strategies for Coping with Stress According to Mini-COPE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Technique | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | A type of psychotherapy that helps patients identify and change negative thoughts and behaviors. | Reduces anxiety, depression, and stress; improves coping skills and overall quality of life. |

| Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | A program that incorporates mindfulness meditation to help patients focus on the present moment. | Reduces stress, anxiety, and depression; enhances emotional regulation and overall well-being. |

| Support Groups | Group meetings where patients can share experiences and receive emotional support from peers. | Provides emotional support, reduces feelings of isolation, and improves coping strategies. |

| Exercise | Physical activities such as walking, yoga, or tai chi, tailored to the patient’s abilities. | Improves physical health, reduces fatigue, and enhances mood and overall quality of life. |

| Relaxation Techniques | Techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery. | Reduces stress and anxiety, promotes relaxation, and improves sleep quality. |

| Art Therapy | Creative activities such as drawing, painting, or music therapy to express emotions. | Provides a non-verbal outlet for emotions, reduces stress, and enhances emotional well-being. |

| Educational Interventions | Providing patients with information about their disease, treatment options, and coping strategies. | Reduces uncertainty, empowers patients, and improves adherence to treatment and overall outcomes. |

References

- World Health Organization. Breast Cancer. Key Fact. March 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Riesling, S.; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Cancer Information System. Available online: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Barrios, C.H. Global challenges in breast cancer detection and treatment. Breast 2022, 62 (Suppl. 1), S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GLOBOCAN 2022, Breast Cancer Fact Sheet. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/20-breast-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- National Cancer Registry. Available online: https://onkologia.org.pl/pl/raporty (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Borgi, M.; Collacchi, B.; Ortona, E.; Cirulli, F. Stress and coping in women with breast cancer: Unravelling the mechanisms to improve resilience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 119, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska, U.; Barańska, K.; Michałek, I.; Olasek, P.; Miklewska, M.; Didkowska, J.A. Biuletyn Nowotwory Złośliwe w Polsce w 2020 Roku, Cancer in Poland in 2020; Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie National Institute of Oncology—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dafni, U.; Tsourti, Z.; Alatsathianos, I. Breast Cancer Statistics in the European Union: Incidence and Survival across European Countries. Breast Care 2019, 14, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, Y.; Fang, K.; Xue, Z.; Hao, X.; Wang, Z. The use of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavarani, A.M.; Marz Abadi, E.A.; Kalkhoran, M.H. Stress: Facts and Theories through Literature Review. Int. J. Med. Rev. 2015, 2, 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Aschbacher, K.; O’Donovan, A.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Su, Y.; Epel, E. Good stress, bad stress, and oxidative stress: Insights from anticipatory cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1698–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, M.J.; Riba, M.B.; Spiegel, D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoleń, E.; Jarema, M.; Hombek, K.; Słysz, M.; Kalita, K. Acceptance and adaptation to the disease in patients treated oncologically. Nurs. Probl./Probl. Pielęgniarstwa 2018, 26, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, R.; Agosta, M.; Fellman, B.; Reddy, A.; Baldwin, S.; Arthur, J.; Haider, A.; Carmack, C.; Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Coping Strategies and Associated Symptom Burden Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2024, 29, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahane, V.; Deshpande, Y. Examining the Role of Resilience, Coping Strategies, Psychological Distress, and General Well-being Among Cancer Patients: A Serial Multiple Mediator Model. Indian J. Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. Mini-COPE: Inventory for Measuring Coping with Stress. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP. Available online: https://www.practest.com.pl/sklep/test/Mini-COPE (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Notice of the Marshal of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland of September 27, 2011, on the Announcement of the Consolidated Text of the Act on the Professions of Doctor and Dentist. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20112771634 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Yan, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, M.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zou, Z. Chronic stress in solid tumor development: From mechanisms to interventions. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.S.; de Haes, J.C. Denial in cancer patients, an explorative review. Psychooncology 2007, 16, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbach, S.; Kowalski, C.; Enders, A.; Pfaff, H.; Ernstmann, N.; Nakata, H. Psycho-oncology care in breast cancer: Determinants of use and need over the course of the disease. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27 (Suppl. 3), ckx189.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fopka-Kowalczyk, M. Providing Support and Spiritual Care to People with Chronic Diseases. Paedagog. Christ. 2020, 2, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Huang, Q.; Yuan, C. Profiles of instrumental, emotional, and informational support in Chinese breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A latent class analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, M.; Białczyk, K. Coping Styles and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvillemo, P.; Bränström, R. Coping with Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durosini, I.; Triberti, S.; Savioni, L.; Sebri, V.; Pravettoni, G. The Role of Emotion-Related Abilities in the Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuné-Boyle, I.C.V.; Stygall, J.; Keshtgar, M.R.S.; Davidson, T.I.; Newman, S.P. The Impact of a Breast Cancer Diagnosis on Religious/Spiritual Beliefs and Practices in the UK. J. Relig. Health 2010, 50, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, D.; Cognetta, C.; Repetto, C.; Serino, S.; Toniolo, D.; Scanzi, F.; Riva, G. Promoting Emotional Well-Being in Older Breast Cancer Patients: Results From an eHealth Intervention. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joaquín-Mingorance, M.; Arbinaga, F.; Carmona-Márquez, J.; Bayo-Calero, J. Coping strategies and self-esteem in women with breast cancer. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2019, 35, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, A.; Çavuşoğlu, E. The Effect of Spiritual Therapies on the Quality of Life of Women with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Relig. Health 2025, 64, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska, I.; Szot, L. Preference for Religious Coping Strategies and Passive versus Active Coping Styles among Seniors Exhibiting Aggressive Behaviors. Religions 2021, 12, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougle, L.; Konrath, S.; Walk, M.; Handy, F. Religious and Secular Coping Strategies and Mortality Risk among Older Adults. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 123, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G.; Al Zaben, F. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 56, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, T.L.; Guirguis-Younger, M. Religious and Spiritual Coping: Current Theory and Research. J. Relig. Health 2019, 58, 2201–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, A.; Krzemkowska, E.; Rhone, P. Acceptance of Illness after Surgery in Patients with Breast Cancer in the Early Postoperative Period. Pol. Przegl. Chir. 2015, 87, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulchycki, M.; Halder, H.R.; Askin, N.; Rabbani, R.; Schulte, F.; Jeyaraman, M.M.; Sung, L.; Louis, D.; Lix, L.; Garland, A.; et al. Aerobic Physical Activity and Depression Among Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2437964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Yu, J.; Huang, H. Effect of resistance exercise on physical fitness, quality of life, and fatigue in patients with cancer: A systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1393902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-H.; Lai, C.-H.; Hou, Y.-J.; Kuo, L.-T. The Efficacy of Music Intervention in Patients with Cancer Receiving Radiation Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, F.; Martin, Z.-S.; Hertrampf, R.-S.; Gäbel, C.; Kessler, J.; Ditzen, B.; Warth, M. Music Therapy in the Psychosocial Treatment of Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witte, M.; Pinho, A.D.S.; Stams, G.J.; Moonen, X.; Bos, A.E.R.; van Hooren, S. Music Therapy for Stress Reduction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, L.J.L.; Tavares, V.B.; Carneiro, S.R.; Neves, L.M.T. The effect of physical activity on markers of oxidative and antioxidant stress in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, L.M.; Park, C.L.; Hingorany, P. The Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Conscious. Theory Res. Pract. 2023. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Rozmiarek, M.; Sobczyk, K.; Działach, E.; Górski, M.; Kobza, J. The Level of COVID-19 Anxiety among Oncology Patients in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Białek-Dratwa, A. The Impact of the Epidemiological Situation Resulting From COVID-19 Pandemic on Selected Aspects of Mental Health Among Patients with Cancer-Silesia Province (Poland). Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 857326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Działach, E.; Buczkowska, M.; Górski, M.; Nowara, E. Feelings Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Patients Treated in the Oncology Clinics. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.E.; Zelinski, E.L.; Toivonen, K.I.; Flynn, M.; Qureshi, M.; Piedalue, K.A.; Grant, R. Mind-Body Therapies in Cancer: What Is the Latest Evidence? Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustian, K.M.; Alfano, C.M.; Heckler, C.; Kleckner, I.R.; Kleckner, A.S.; Leach, C.R.; Mohr, D.; Palesh, O.; Peppone, L.J.; Piper, B.F. Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainal, N.Z.; Booth, S.; Huppert, F.A. The Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Mental Health of Breast Cancer Patients: A Meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, H.; Schuler, M.; Richard, M.; Heckl, U.; Weis, J.; Küffner, R. Effects of Psycho-Oncologic Interventions on Emotional Distress and Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleta-Pilarska, A. Acceptance of disease in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann. Acad. Med. Siles. 2022, 76, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/esmo-clinical-practice-guidelines-breast-cancer (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. Available online: https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/22/5/article-p331.xml (accessed on 27 February 2025).

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of women | 111 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 45.6 ± 10.76 |

| Age category | |

| 21–44 years | 49 (44.14%) |

| 45–67 years | 62 (55.86%) |

| Marital status | |

| married | 72 (64.9%) |

| single | 24 (22.5%) |

| divorced | 15 (10.8%) |

| Having children | 78 (70.3%) |

| Age at breast cancer diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 41.9 ± 12.23 |

| Highest number of diagnoses at age | |

| 46 years | 9 (7.77%) |

| 55 years | 9 (7.77%) |

| 56 years | 9 (7.77%) |

| Type of cancer | |

| malignant | 103 (92.8%) |

| benign | 8 (7.2%) |

| Strategies for Coping with Stress | Arithmetic Mean | SD | Min. | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active coping | 1.29 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Planning | 1.12 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Positive revaluation | 1.22 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Acceptance | 1.60 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Sense of humor | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 2.50 |

| Turning to religion | 1.07 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Seeking emotional support | 2.12 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| Seeking instrumental support | 2.06 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| Dealing with something else | 1.95 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| Denying | 1.75 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Discharge | 1.55 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

| Using psychoactive substances | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.50 |

| Cessation of activities | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.50 |

| Blaming yourself | 1.22 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.50 |

| Strategies for Coping with Stress | Age | Arithmetic Mean | SD | Min. | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Max. | Mann–Whitney U Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active coping | 1 2 | 1.42 1.19 | 0.85 0.71 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 1.19 p = 0.24 |

| Planning | 1 2 | 1.22 1.03 | 0.77 0.62 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 0.95 p = 0.37 |

| Positive revaluation | 1 2 | 1.20 1.23 | 0.67 0.61 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −0.02 p = 0.98 |

| Acceptance | 1 2 | 1.63 1.57 | 0.55 0.56 | 1.00 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 0.57 p = 0.57 |

| Sense of humor | 1 2 | 0.37 0.24 | 0.51 0.32 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.00 | 0.50 2.00 | 2.50 1.50 | Z = 1.06 p = 0.29 |

| Turning to religion | 1 2 | 0.79 1.29 | 0.85 0.67 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 1.00 | 0.50 1.00 | 1.00 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −3.74 p < 0.001 |

| Seeking emotional support | 1 2 | 2.15 2.10 | 0.58 0.55 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 0.64 p = 0.52 |

| Seeking instrumental support | 1 2 | 2.01 2.10 | 0.51 0.44 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −1.05 p = 0.29 |

| Dealing with something else | 1 2 | 1.99 1.91 | 0.58 0.55 | 0.50 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 0.75 p = 0.46 |

| Denying | 1 2 | 1.66 1.81 | 0.81 0.65 | 0.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.50 | 1.50 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −1.01 p = 0.31 |

| Discharge | 1 2 | 1.55 1.56 | 0.49 0.47 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.50 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 3.00 | Z = 0.20 p = 0.84 |

| Using psychoactive substances | 1 2 | 0.19 0.34 | 0.35 0.56 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.00 1.50 | Z = −1.41 p = 0.16 |

| Cessation of activities | 1 2 | 0.85 0.93 | 0.52 0.52 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.50 | Z = −0.75 p = 0.45 |

| Blaming yourself | 1 2 | 1.23 1.21 | 0.65 0.54 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 2.50 2.50 | Z = 0.18 p = 0.86 |

| Strategies for Coping with Stress | Having Children | Arithmetic Mean | SD | Min. | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Max. | Mann–Whitney U Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active coping | 1 2 | 1.23 1.44 | 0.71 0.92 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −1.04 p = 0.30 |

| Planning | 1 2 | 1.03 1.32 | 0.64 0.79 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −1.66 p = 0.10 |

| Positive revaluation | 1 2 | 1.20 1.26 | 0.63 0.66 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −0.55 p = 0.59 |

| Acceptance | 1 2 | 1.56 1.70 | 0.55 0.56 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 3.00 2.50 | Z = −1.48 p = 0.14 |

| Sense of humor | 1 2 | 0.31 0.27 | 0.46 0.31 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 | 2.50 1.00 | Z = −0.14 p = 0.89 |

| Turning to religion | 1 2 | 1.24 0.67 | 0.79 0.67 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.00 | 1.00 0.50 | 2.00 1.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 3.55 p < 0.001 |

| Seeking emotional support | 1 2 | 2.10 2.17 | 0.58 0.53 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −0.77 p = 0.44 |

| Seeking instrumental support | 1 2 | 2.07 2.03 | 0.46 0.51 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 0.34 p = 0.74 |

| Dealing with something else | 1 2 | 1.89 2.08 | 0.58 0.50 | 0.50 1.00 | 1.50 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = −1.63 p = 0.10 |

| Denying | 1 2 | 1.83 1.55 | 0.67 0.81 | 0.50 0.00 | 1.50 1.00 | 2.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 | 3.00 3.00 | Z = 1.94 p = 0.05 |

| Discharge | 1 2 | 1.53 1.61 | 0.49 0.45 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.00 1.50 | 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 | 3.00 2.50 | Z = −0.85 p = 0.40 |

| Using psychoactive substances | 1 2 | 0.29 0.23 | 0.43 0.40 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.50 1.50 | Z = 0.61 p = 0.54 |

| Cessation of activities | 1 2 | 0.91 0.85 | 0.46 0.64 | 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.50 | Z = 0.68 p = 0.50 |

| Blaming yourself | 1 2 | 1.24 1.17 | 0.55 0.69 | 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 | 2.50 2.50 | Z = 0.55 p = 0.58 |

| Strategies for Coping with Stress Active Coping | Marital Status | Arithmetic Mean | SD | Min. | Lower Quartile | Median | Upper Quartile | Max. | Mann–Whitney U Test | Dunn–Bonferroni Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Active coping | 1 2 3 | 1.32 1.25 1.28 | 0.84 0.72 0.75 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.50 1.50 | 3.00 2.50 3.00 | H = 2.95 p = 0.40 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Planning | 1 2 3 | 1.18 0.92 1.10 | 0.76 0.63 0.66 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.50 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.00 1.50 | 3.00 2.00 3.00 | H = 4.26 p = 0.23 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Positive revaluation | 1 2 3 | 1.16 1.08 1.26 | 0.66 0.51 0.66 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 1.75 | 3.00 2.00 3.00 | H = 1.11 p = 0.77 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Acceptance | 1 2 3 | 1.66 1.50 1.60 | 0.61 0.48 0.55 | 0.50 1.00 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.00 3.00 | H = 1.73 p = 0.63 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Sense of humor | 1 2 3 | 0.32 0.25 0.31 | 0.28 0.58 0.43 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.25 0.50 | 1.00 2.00 2.50 | H = 3.49 p = 0.32 | 0.88 1.00 | 0.88 1.00 | 1.00 100 |

| Turning to religion | 1 2 3 | 0.56 1.13 1.19 | 0.49 1.03 0.75 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.25 0.50 | 0.50 0.75 1.00 | 1.00 2.00 2.00 | 1.50 3.00 3.00 | H = 15.68 p = 0.001 | 0.45 0.003 | 0.45 1.00 | 0.003 1.00 |

| Seeking emotional support | 1 2 3 | 2.08 2.17 2.13 | 0.54 0.58 0.56 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 3.00 | H = 2.36 p = 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Seeking instrumental support | 1 2 3 | 1.98 2.08 2.07 | 0.49 0.42 0.48 | 1.00 1.50 1.00 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.00 2.25 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 3.00 | H = 3.36 p = 0.34 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Dealing with something else | 1 2 3 | 2.04 2.04 1.90 | 0.54 0.50 0.56 | 1.00 1.50 0.50 | 2.00 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 2.00 2.00 | 2.50 2.50 2.50 | 3.00 3.00 3.00 | H = 4.22 p = 0.24 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Denying | 1 2 3 | 1.68 1.58 1.83 | 0.71 0.56 0.73 | 1.00 1.00 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.75 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 2.50 | 3.00 2.50 3.00 | H = 4.78 p = 0.19 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Discharge | 1 2 3 | 1.58 1.42 1.56 | 0.43 0.42 0.50 | 0.50 0.50 0.50 | 1.50 1.25 1.00 | 1.50 1.50 1.50 | 2.00 1.50 2.00 | 2.00 2.00 3.00 | H = 4.00 p = 0.26 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Using psychoactive substances | 1 2 3 | 0.18 0.08 0.35 | 0.38 0.29 0.44 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.00 0.00 0.75 | 1.50 1.00 1.50 | H = 7.40 p = 0.06 | 1.00 0.77 | 1.00 0.37 | 0.77 0.37 |

| Cessation of activities | 1 2 3 | 0.84 0.92 0.90 | 0.62 0.42 0.50 | 0.00 0.00 0.00 | 0.50 0.75 0.50 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 2.50 1.50 2.00 | H = 0.55 p = 0.91 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

| Blaming yourself | 1 2 3 | 1.24 1.04 1.26 | 0.69 0.78 0.50 | 0.00 0.00 0.50 | 1.00 0.25 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 1.00 | 1.50 1.75 1.50 | 2.50 2.00 2.50 | H = 3.75 p = 0.29 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 | 1.00 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wypych-Ślusarska, A.; Ociepka, S.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Głogowska-Ligus, J.; Oleksiuk, K.; Słowiński, J.; Yanakieva, A. Ways of Coping with Stress in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060609

Wypych-Ślusarska A, Ociepka S, Krupa-Kotara K, Głogowska-Ligus J, Oleksiuk K, Słowiński J, Yanakieva A. Ways of Coping with Stress in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060609

Chicago/Turabian StyleWypych-Ślusarska, Agata, Sandra Ociepka, Karolina Krupa-Kotara, Joanna Głogowska-Ligus, Klaudia Oleksiuk, Jerzy Słowiński, and Antoniya Yanakieva. 2025. "Ways of Coping with Stress in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Study" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060609

APA StyleWypych-Ślusarska, A., Ociepka, S., Krupa-Kotara, K., Głogowska-Ligus, J., Oleksiuk, K., Słowiński, J., & Yanakieva, A. (2025). Ways of Coping with Stress in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Healthcare, 13(6), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060609