Bulwark Effect of Response in a Causal Model of Disruptive Clinician Behavior: A Quantitative Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact in Japanese General Hospitals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminary Survey

2.2. Procedures and Participants

2.3. Survey Items

2.4. Study Design and Setting

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of Differences Between Hospitals

3.2. Confirming the Reliability of the Indicators

3.3. Compression of Indicators

3.4. Validation of DCB Triggers and Impact

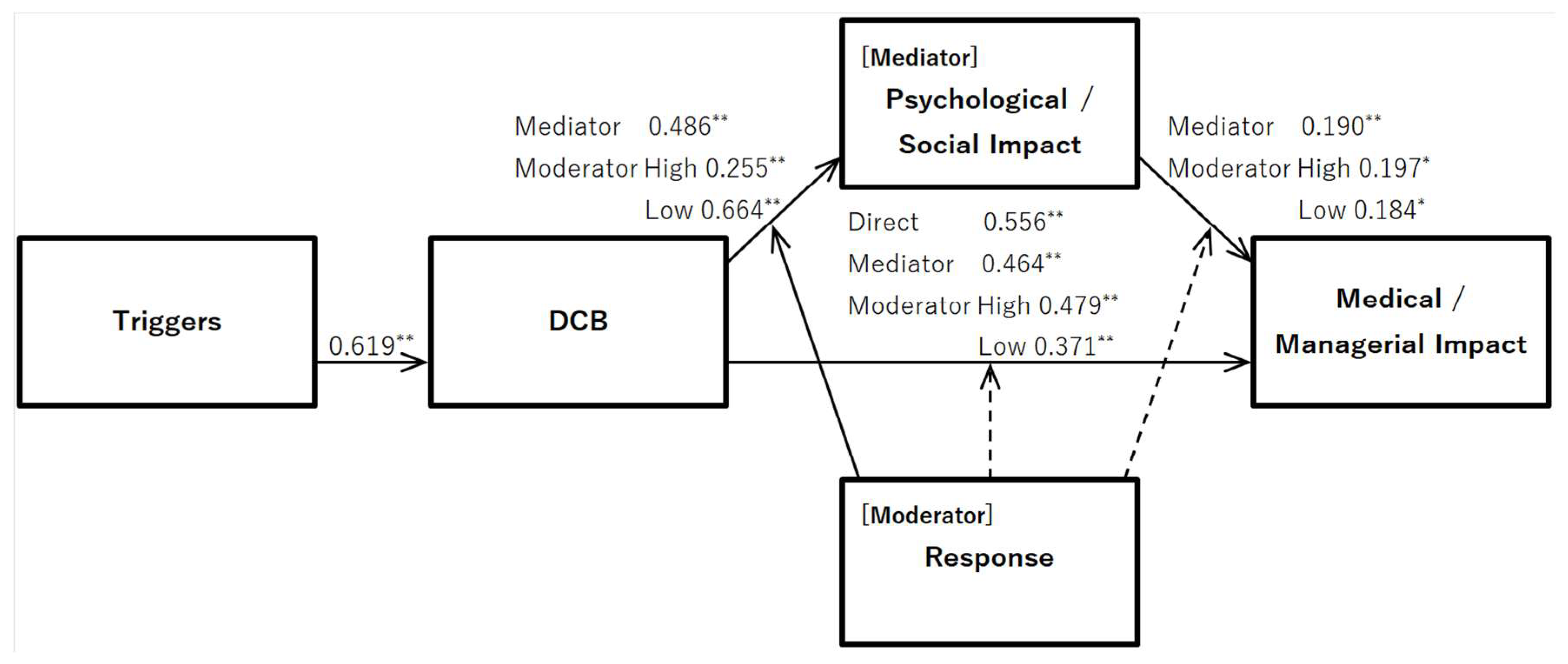

3.5. Examining the Indirect Effects of Psychological/Social Impact

3.6. Verification of Moderate Effects of Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCB | Disruptive clinician behavior |

References

- Rosenstein, A.H. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. Am. J. Nurs. 2002, 102, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, W.; Pichert, J.W.; Hickson, G.B.; Braddy, C.H.; Brown, A.J.; Catron, T.F.; Moore, I.N.; Stampfle, M.R.; Webb, L.E.; Cooper, W.O. Qualitative content analysis of coworkers’ safety reports of unprofessional behavior by physicians and advanced practice professionals. J. Patient Saf. 2021, 17, e883–e889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, A.H. Disruptive and unprofessional behaviors. In Physician Mental Health and Well-Being; Brower, K.J., Riba, M.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, A.H.; Naylor, B. Incidence and impact of physician and nurse disruptive behaviors in the emergency department. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 43, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. Understanding and managing physicians with disruptive behavior. In Enhancing Physician Performance-Advanced Principles of Medical Management; Ransom, S.B., Pinsky, W.W., Tropman, J.E., Eds.; American College of Physician Executives: Tampa, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, M.A.; Scholl, A.T. Why we need a single definition of disruptive behavior. Cureus 2018, 10, e2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, M.; Shimamura, M.; Miyazaki, H.; Inaba, K. Development of a Psychological Scale for Measuring Disruptive Clinician Behavior. J. Patient Saf. 2023, 19, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert: Behaviors That Undermine a Culture of Safety. 2008. Updated 2021. pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea-40-intimidating-disruptive-behaviors-final2.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- The Joint Commission. LD_Code of Conduct Policy. July 2020. Available online: https://store.jcrinc.com/assets/1/7/POLB_Behavioral_Sample_Pages.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Nagao, Y. The relationship between disruptive behavior and the quality of medical care in surgical treatment in Japan (Honpou no syujutusinryo niokeru disruptive behavior to iryonoshitu no kankei in Japanese). Uehara Meml. Fund. Rep. 2012, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein, A.H.; O’Daniel, M. A Survey of the Impact of Disruptive Behaviors and Communication Defects on Patient Safety. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2008, 34, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, D.; Bae, S.-H.; Karlowicz, K.A.; Kim, M.T. Do clinician disruptive behaviors make an unsafe environment for patients? J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2016, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, M.; Shimamura, M.; Inaba, K. Influence of disruptive behaviors in Japanese medical setting. J. Clin. Ethics 2021, 9, 29–40. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, O. Disruptive Physician Behavior; American College of Physician Executives: Tampa, FL, USA, 2011; Available online: https://kff.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/03/quantiamd_whitepaper_acpe_15may2011.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Braun, K.; Christle, D.; Walker, D.; Tiwanak, G. Verbal abuse of nurses and non-nurses. Nurs. Manag. 1991, 22, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.L.; Diedrich, A.; Phelps, C.L.; Choi, M. Bullies at work: The impact of horizontal hostility in the hospital setting and intent to leave. J. Nurs. Adm. 2011, 41, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, H.J.; Abu Shosha, G.M.; Al-Kalaldeh, M.T.; Oweidat, I.A.; Al-Mugheed, K.; Alsenany, S.A.; Farghaly Abdelaliem, S.M. Perceived Relationship Between Horizontal Violence and Patient Safety Culture Among Nurses. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2023, 16, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, R. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida, K. Introduction to Confucianism (Jyukyo Nyumon in Japanese); Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Latessa, R.A.; Galvin, S.L.; Swendiman, R.A.; Onyango, J.; Ostrach, B.; Edmondson, A.C.; Davis, S.A.; Hirsh, D.A. Psychological safety and accountability in longitudinal integrated clerkships: A dual institution qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergerich, E.; Boland, D.; Scott, M.A. Hierarchies in interprofessional training. J. Interprofessional Care 2019, 33, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Nyberg, D.; Walrath, J.M.; Kim, M.T.; Graham, G. Development and validation of the Johns Hopkins Disruptive Clinician Behavior Survey. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2014, 30, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, J.V.; Thompson, N.; Sostre, G.; Deitte, L. The cost of disruptive and unprofessional behaviors in health care. Acad. Radiol. 2013, 20, 1074–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. The impact of interprofessional incivility on medical performance, service and patient care: A systematic review. Future Healthc. J. 2023, 10, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, C.S.; Kovner, C.T.; Obeidat, R.F.; Budin, W.C. Positive work environments of early-career registered nurses and the correlation with physician verbal abuse. Nurs. Outlook 2013, 61, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunger, J.A.; Maben, J.; Abrams, R.; Wright, J.M.; Mannion, R.; Pearson, M.; Jones, A.; Westbrook, J.I. Drivers of unprofessional behaviour between staff in acute care hospitals: A realist review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstein, A.H. Physician disruptive behaviors: Five year progress report. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 3, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisah, C.; Williams, B.; Hockey, P.; Lees, P.; Wright, D.; Rosenstein, A. Pragmatic Systemic Solutions to the Wicked and Persistent Problem of the Unprofessional Disruptive Physician in the Health System. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessey, J.A.; Demarco, R.F.; Gaffney, D.A.; Budin, W.C. Bullying of staff registered nurses in the workplace: A preliminary study for developing personal and organizational strategies for the transformation of hostile to healthy workplace environments. J. Prof. Nurs. 2009, 25, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafranca, A.; Hamlin, C.; Enns, S.; Jacobsohn, E. Disruptive behaviour in the perioperative setting: A contemporary review. Les comportements perturbateurs dans le contexte périopératoire: Un compte rendu contemporain. Can. J. Anaesth./J. Can. D’anesthesie 2017, 64, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, S.; Muhonen, T. Factors influencing the behavior of bystanders to workplace bullying in healthcare-A qualitative descriptive interview study. Res. Nurs. Health 2022, 45, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Jones, L.; Harvey, C.; Munday, J. Workplace bullying, burnout and resilience amongst perioperative nurses in Australia: A descriptive correlational study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.H.; Benham-Hutchins, M. The Influence of Bullying on Nursing Practice Errors: A Systematic Review. AORN J. 2020, 111, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. New graduate registered nurses’ exposure to negative workplace behaviour in the acute care setting: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonson, C.; Zelonka, C. Our Own Worst Enemies: The Nurse Bullying Epidemic. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2019, 43, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, D.J.; Cohen, R.R.; Burke, M.J.; McLendon, C.L. Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Leal, P.; Leal-Costa, C.; Díaz-Agea, J.L.; Jiménez-Ruiz, I.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; De Souza Oliveira, A.C. Disruptive Behavior at Hospitals and Factors Associated to Safer Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, H. The Little Book of Restorative Justice; Good Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetti, G.; Schaufeli, W.B. The impact of engaging leadership on employee engagement and team effectiveness: A longitudinal, multi-level study on the mediating role of personal- and team resources. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, L.B.; Van Dijk, E.; De Cremer, D.; Wilke, H.A.M. Undermining trust and cooperation: The paradox of sanctioning systems in social dilemmas. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interpersonal aggression | ||

| Ignoring a | ||

| Incivility b | ||

| Physical violence | ||

| Psychological aggression | ||

| Intimidation a | ||

| Abusive language b | ||

| Reproof | ||

| Threat c | ||

| Job-related aggression | ||

| Mismanagement practice | ||

| Non-supportive coercion c | ||

| Arbitrary decision | ||

| Passive aggression | ||

| Hospital A | Hospital B | |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | 20 (23.8%) | 11 (6.4%) |

| Nursing professional | 38 (45.2) | 101 (58.7) |

| Paramedic | 21 (25.0) | 38 (22.1) |

| Non-medical professional | 5 (6.0) | 22 (12.8) |

| Female | 48 (57.1) | 123 (71.5) |

| Male | 35 (41.7) | 44 (25.6) |

| Unanswered | 1 (1.2) | 5 (2.9) |

| Age (years) 20s | 14 (16.7) | 21 (12.2) |

| 30s | 21 (25.0) | 40 (23.3) |

| 40s | 25 (29.8) | 51 (29.7) |

| 50s | 17 (20.0) | 36 (20.9) |

| 60s | 5 (6.0) | 16 (9.3) |

| Unanswered | 2 (2.4) | 8 (4.7) |

| Total | 84 | 172 |

| M | SD | w | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCB | 1st principal component contribution rate 35.03% | 0.933 | |||||

| Ignoring | 1st principal component loading | 0.605 | 2.51 | 1.50 | |||

| Incivility | 0.751 | 3.25 | 1.57 | ||||

| Reproof | 0.839 | 3.03 | 1.50 | ||||

| Threat | 0.837 | 3.79 | 1.50 | ||||

| Intimidation | 0.739 | 2.67 | 1.44 | ||||

| Abusive language | 0.845 | 3.50 | 1.54 | ||||

| Physical violence | 0.351 | 1.24 | 0.69 | ||||

| Non-supportive coercion | 0.684 | 1.77 | 1.02 | ||||

| Arbitrary decision | 0.810 | 2.30 | 1.22 | ||||

| Passive aggression | 0.746 | 2.41 | 1.31 | ||||

| Triggers | 1st principal component contribution rate 35.03% | 0.789 | |||||

| Perpetrator competence | 1st principal component loading | 0.575 | 2.80 | 1.47 | 0.753 | ||

| The perpetrator lacked knowledge or experience in the job | 2.44 | 1.45 | |||||

| The perpetrator lacked competence and aptitude for the job | 3.17 | 1.80 | |||||

| Perpetrator’s personality | 1st principal component loading | 0.669 | 3.84 | 1.43 | 0.651 | ||

| The perpetrator had communication and socialization problems | 4.28 | 1.59 | |||||

| The perpetrator had a lax and inconsiderate personality | 3.40 | 1.74 | |||||

| Victim’s competence | 1st principal component loading | 0.477 | 2.64 | 1.29 | 0.859 | ||

| The victim lacked knowledge or experience in the job | 2.75 | 1.44 | |||||

| The victim lacked competence or aptitude for the job | 2.53 | 1.32 | |||||

| Victim’s personality | 1st principal component loading | 0.556 | 1.93 | 0.99 | 0.782 | ||

| The victim had problems with communication and socializing | 2.16 | 1.21 | |||||

| The victim had a lax and inconsiderate personality | 1.70 | 0.99 | |||||

| Press of business | 1st principal component loading | 0.518 | 3.42 | 1.76 | 0.878 | ||

| There was a regular shortage of staff at the workplace | 3.46 | 1.89 | |||||

| Busy or urgent situation | 3.38 | 1.84 | |||||

| Normalization | 1st principal component loading | 0.721 | 4.02 | 1.53 | 0.681 | ||

| There was no one around to blame | 4.45 | 1.65 | |||||

| Disruptive behavior was the norm in the workplace | 3.59 | 1.85 | |||||

| Response | 1st principal component contribution rate 34.91% | 0.868 | |||||

| Direct action by the victim | 1st principal component loading | 0.488 | 2.90 | 1.52 | 0.854 | ||

| The victim tried to solve the problem by confronting the perpetrator and the problem | 2.95 | 1.61 | |||||

| The victim tried to clear up the perpetrator’s misunderstanding | 2.85 | 1.64 | |||||

| Requested instrumental support | 1st principal component loading | 0.824 | 3.06 | 1.51 | 0.669 | ||

| The victim told others about the harm | 3.24 | 1.81 | |||||

| The victim asked for help from others | 2.88 | 1.70 | |||||

| Requested emotional support | 1st principal component loading | 0.764 | 3.73 | 1.53 | 0.784 | ||

| The victim talked to others | 3.82 | 1.70 | |||||

| The victim got emotional support from others | 3.64 | 1.68 | |||||

| Avoidance | 1st principal component loading | 0.156 | 3.90 | 1.42 | 0.480 | ||

| The victim distanced themself from the perpetrator | 4.03 | 1.79 | |||||

| The victim tried not to care | 3.78 | 1.72 | |||||

| Servile submission | 1st principal component loading | −0.031 | 3.26 | 1.60 | 0.733 | ||

| The victim had no choice but to give up | 3.58 | 1.83 | |||||

| The victim did what the perpetrator wanted them to do | 2.94 | 1.79 | |||||

| Direct action by others | 1st principal component loading | 0.797 | 2.05 | 1.29 | 0.890 | ||

| Others systematically took remedial measures | 2.05 | 1.37 | |||||

| Others tried to solve the problem by confronting the perpetrator and the problem | 2.05 | 1.35 | |||||

| Arbitration | 1st principal component loading | 0.791 | 1.86 | 1.19 | 0.812 | ||

| Others intervened between the perpetrator and the victim and tried to mediate | 1.92 | 1.37 | |||||

| Others pacified the perpetrator | 1.81 | 1.24 | |||||

| Adulation | 1st principal component loading | 0.081 | 2.28 | 1.32 | 0.782 | ||

| Others did what the perpetrator wanted them to do | 2.60 | 1.57 | |||||

| Others sympathized with the perpetrator | 1.95 | 1.36 | |||||

| Psychological/social impact | 1st principal component contribution rate 80.33% | 0.923 | |||||

| Psychological state | 1st principal component loading | 0.919 | 4.13 | 1.52 | 0.801 | ||

| Became physically and mentally unwell | 3.99 | 1.69 | |||||

| Lost motivation to work | 4.26 | 1.65 | |||||

| Quality of care | 1st principal component loading | 0.852 | 3.00 | 1.61 | 0.789 | ||

| Became confused and unable to think calmly | 3.29 | 1.83 | |||||

| Impaired ability to provide medical care | 2.70 | 1.73 | |||||

| Interpersonal relationships | 1st principal component loading | 0.917 | 3.96 | 1.51 | 0.755 | ||

| Communication became difficult | 4.54 | 1.52 | |||||

| Difficulty staying in the workplace | 3.39 | 1.84 | |||||

| Medical/managerial impact | 1st principal component contribution rate 69.47% | 0.875 | |||||

| Quality of medical care | 1st principal component loading | 0.892 | 3.31 | 1.62 | 0.768 | ||

| The workload increased because of staff shortages | 3.09 | 1.83 | |||||

| Hindered the organization’s improvement in medical quality and safety | 3.53 | 1.78 | |||||

| Hospital management | 1st principal component loading | 0.785 | 2.36 | 1.34 | 0.749 | ||

| Damaged the hospital’s social credibility and reputation | 2.66 | 1.68 | |||||

| Caused financial damage to hospital management | 2.05 | 1.34 | |||||

| Workplace relations | 1st principal component loading | 0.820 | 3.90 | 1.61 | 0.914 | ||

| Deteriorated the workplace atmosphere | 4.06 | 1.66 | |||||

| Workplace teamwork deteriorated | 3.75 | 1.69 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujimoto, M.; Shimamura, M.; Miyazaki, H. Bulwark Effect of Response in a Causal Model of Disruptive Clinician Behavior: A Quantitative Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact in Japanese General Hospitals. Healthcare 2025, 13, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050510

Fujimoto M, Shimamura M, Miyazaki H. Bulwark Effect of Response in a Causal Model of Disruptive Clinician Behavior: A Quantitative Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact in Japanese General Hospitals. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050510

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujimoto, Manabu, Mika Shimamura, and Hiroaki Miyazaki. 2025. "Bulwark Effect of Response in a Causal Model of Disruptive Clinician Behavior: A Quantitative Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact in Japanese General Hospitals" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050510

APA StyleFujimoto, M., Shimamura, M., & Miyazaki, H. (2025). Bulwark Effect of Response in a Causal Model of Disruptive Clinician Behavior: A Quantitative Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact in Japanese General Hospitals. Healthcare, 13(5), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050510