Development and Validation of the Pregnancy Guilt Assessment Scale (PGAS): A Specific Tool for Assessing Guilt in Pregnancy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Conceptualization of Guilt During Pregnancy

1.3. Need for a Specific Measure of Guilt During Pregnancy

1.4. Objectives of the Study

1.5. The Present Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.1.1. Phase 1—Item Generation and Comprehension Review

- Focus Groups (n = 17)

- Cognitive Debriefing (n = 8)

2.1.2. Phase 2—Expert-Based Content Evaluation (n = 3)

2.1.3. Phase 3—Preliminary Examination of the Underlying Factor Structure (n = 85)

2.1.4. Phase 4—Factor Structure Replication, Reliability, Group Comparisons, and Validity Testing (n = 171)

2.2. Measures

- Guilt in pregnancy

- Antenatal depression

- Prenatal distress

- Positive and negative affect

- Self-esteem

- Perceived social support

- Dispositional guilt

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Phase 1—Item Generation (Focus Groups and Cognitive Debriefing)

2.3.2. Phase 2—Expert-Based Content Evaluation (CVI and Modified Kappa Criteria)

2.3.3. Phase 3—Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

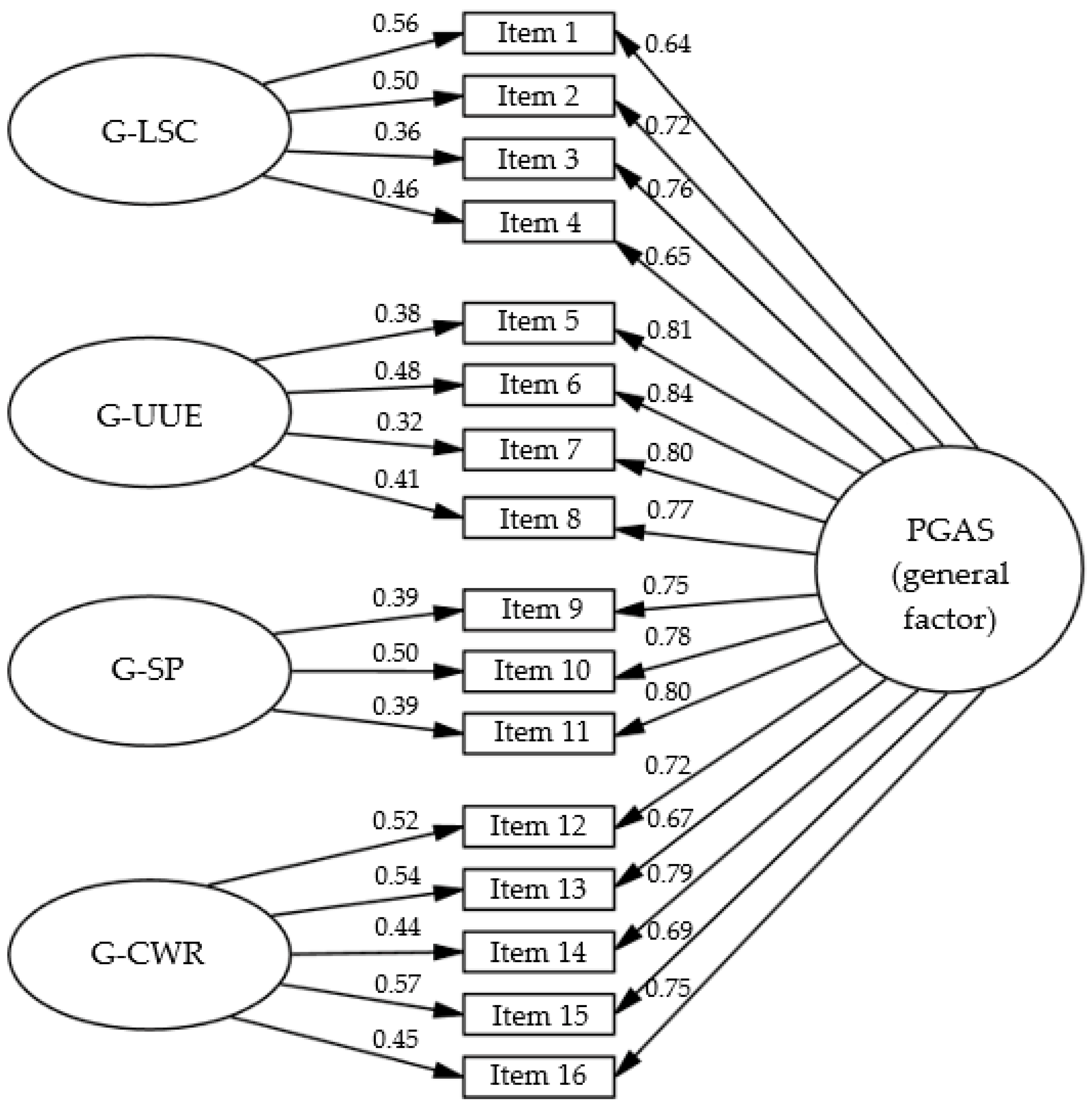

2.3.4. Phase 4—Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Further Validation

3. Results

3.1. Results of Phase 1—Item Generation and Comprehension Review

3.2. Results of Phase 2—Expert-Based Content Evaluation

3.3. Results of Phase 3—Examination of the Underlying Factor Structure

3.4. Results of Phase 4—Factor Structure Replication, Reliability, Group Comparisons, and Validity Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bjelica, A.; Cetkovic, N.; Trninic-Pjevic, A.; Mladenovic-Segedi, L. The phenomenon of pregnancy—A psychological view. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá, P.; Peñacoba, C.; Écija, C.; Gutiérrez, L.; Meireles, L.G.V. Psychological Needs in Spanish Pregnant Women During the Transition to Motherhood: A Qualitative Study. Societies 2025, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.; O’Donoghue, E.; Helm, J.; Gentilcore, R.; Hussain, A. ‘Some Days Are Not a Good Day to Be a Mum’: Exploring Lived Experiences of Guilt and Shame in the Early Postpartum Period. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 3019–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotkirch, A.; Janhunen, K. Maternal Guilt. Evol. Psychol. 2010, 8, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, J. Mothering, Guilt and Shame. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.; Meredith, P.; Whittingham, K.; Ziviani, J. Shame and guilt in the postnatal period: A systematic review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2021, 39, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer-Can, S.; Yildiz, S.; Torun, R.; Omeroglu, I.; Golbasi, H. Levels of anxiety, depression, self-esteem, and guilt in women with high-risk pregnancies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.A.; Bogossian, F.; Morawska, A.; Wittkowski, A. “I just feel like I am broken. I am the worst pregnant woman ever”: A qualitative exploration of the “at odds” experience of women’s antenatal distress. Health Care Women Int. 2017, 38, 658–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S.K.; Reynolds, K.A.; Hardman, M.P.; Furer, P. How do prenatal people describe their experiences with anxiety? A qualitative analysis of blog content. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Jesus, J.V.; Sánchez, O.D.R.; Rodrigues, L.; Faria-Schützer, D.B.; Serapilha, A.A.A.; Surita, F.G. Stigma, guilt and motherhood: Experiences of pregnant women with COVID-19 in Brazil. Women Birth 2022, 35, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T. Postpartum Depression: A Metasynthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalegui, L. Una escala para medir culpabilidad (SC-35). Miscelánea Comillas 1993, 51, 485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Yali, A.M.; Lobel, M. Coping and distress in pregnancy: An investigation of medically high risk women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 20, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Perra, O.; Alderdice, F.; Lynn, F.; Lobel, M.; García-García, I.; Peralta-Ramírez, M.I. Psychometric validation of the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ) in pregnant women in Spain. Women Health 2019, 59, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Esteve, L.; Ascaso, C.; Ojuel, J.; Navarro, P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 75, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D.S.; King, D.W.; King, L.A. Focus groups in psychological assessment: Enhancing content validity by consulting members of the target population. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Basic and Advanced Focus Groups; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.B.; Míguez, M.C. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for depression in Spanish pregnant women. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargurevich, R. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión internacional de la Escala de Afecto Positivo y Negativo-forma corta (I-Spanas SF) en estudiantes universitarios. Persona 2010, 13, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Albo, J.; Núñiez, J.L.; Navarro, J.G.; Grijalvo, F. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and validation in university students. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landeta, O.; Calvete, E. Adaptación y validación de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido. Ansiedad Estrés 2002, 8, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T.R. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S. V Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada [Exploratory factor analysis of items: A practical guide, revised and updated]. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. ‘It just gives me a bit of peace of mind’: Australian women’s use of digital media for pregnancy and early motherhood. Societies 2017, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facca, D.; Hall, J.; Hiebert, B.; Donelle, L. Understanding the tensions of “good motherhood” through women’s digital technology use: Descriptive qualitative study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2023, 6, e48934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppes, A. Do women need to have children in order to be fulfilled? A system justification account of the motherhood norm. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutawtah, M.; Campbell, E.; Kubis, H.-P.; Erjavec, M. Women’s experiences of social support during pregnancy: A qualitative systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, M.K. The impact of social comparison via social media on maternal mental health, within the context of the intensive mothering ideology: A scoping review of the literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, H.; Özkan, H. Problematic social media use and its relationship with breastfeeding behaviors and anxiety in social media-native mothers: A mixed-methods study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, N. Pregnant field student’s guilt. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2006, 42, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, A.; Bessett, D.; Steinberg, J.R.; Kavanaugh, M.L.; De Zordo, S.; Becker, D. Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’s Health Issues 2011, 21, S49–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, S.; Leal, I.; Maroco, J. The role of psychological adjustment in the decision-making process for voluntary termination of pregnancy. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2013, 14, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martín-Sánchez, M.B.; Martínez-Borba, V.; Catalá, P.; Osma, J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Suso-Ribera, C. Development and psychometric properties of the maternal ambivalence scale in spanish women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce-Selvi, Ü.; Kantaş, Ö. The psychometric evaluation of the maternal employment guilt scale: A development and validation study. Isg. J. Ind. Relat. Hum. Resour. 2019, 21, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, E.; Granger, C. Maternal guilt and shame: Relationship to postnatal depression and attitudes towards help-seeking. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockol, L.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal women. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, J.; Gemmill, A.W. Screening for perinatal depression. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 28, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.E.; Staud, R.; Price, D.D. Pain Measurement and Brain Activity: Will Neuroimages Replace Pain Ratings? J. Pain 2013, 14, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase and Approach | Objective | Procedure | Sample | Scale Items Retained Per Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Mixed–mainly qualitative) | Item generation and comprehension review | Focus groups with pregnant women to explore guilt-related experiences, followed by research team item development and cognitive debriefing with pregnant participants. | Pregnant women (focus groups: n = 17; cognitive debriefing: n = 8) | From 30 to 22 items |

| 2 (Mixed–mainly quantitative) | Expert-based content evaluation | Expert panel to evaluate content validity via CVI. | Experts (n = 3) | From 22 to 19 items |

| 3 (Quantitative) | Underlying factor structure examination | Preliminary EFA to examine the factor structure and guide item reduction. | Pregnant women (n = 85) | From 19 to 16 items |

| 4 (Quantitative) | Factor structure replication, reliability, group comparisons and validity testing | CFA, internal consistency analyses, t-tests, bivariate correlations, and multiple linear regression. | Pregnant women (n = 171) | 16 items |

| Item Wording | Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | I blame myself for not eating in a completely healthy way during my pregnancy. [Me culpo por no alimentarme de manera completamente saludable durante mi embarazo.] | G-LSC |

| 2. | I feel I am not taking good enough care of my body for my baby’s well-being. [Siento que no estoy cuidando lo suficiente mi cuerpo para el bienestar de mi bebé.] | G-LSC |

| 3. | I reproach myself when I do not follow all medical recommendations to the letter. [Me reprocho cuando no sigo todas las recomendaciones médicas al pie de la letra.] | G-LSC |

| 4. | I reproach myself for not doing enough exercise or physical activity during pregnancy. [Me reprocho por no hacer suficiente ejercicio o actividad física durante la gestación.] | G-LSC |

| 5. | I feel guilty for not enjoying every moment with my baby the way other mothers seem to. [Siento culpa por no disfrutar cada momento con mi bebé como otras madres parecen hacerlo.] | G-UEE |

| 6. | I blame myself for not enjoying every moment of my pregnancy the way I am expected to. [Me culpo por no disfrutar cada momento de mi embarazo como se espera que lo haga.] | G-UEE |

| 7. | I feel guilty for not always feeling happy or grateful during my pregnancy. [Me siento culpable por no sentirme siempre feliz o agradecida durante mi embarazo.] | G-UEE |

| 8. | I feel responsible and guilty for not being able to manage all the emotions associated with pregnancy in a positive way. [Me siento responsable por no poder manejar todas las emociones asociadas con el embarazo de manera positiva.] | G-UEE |

| 9. | I feel bad and guilty if I decide not to follow family traditions or advice about pregnancy. [Me siento mal si decido no seguir tradiciones familiares o consejos sobre el embarazo.] | G-SP |

| 10. | I reproach myself when other people give their opinions about my pregnancy and I think they are right. [Me reprocho cuando otras personas opinan sobre mi embarazo y creo que tienen razón.] | G-SP |

| 11. | Sometimes I feel pressured by other people’s opinions about what I should do and/or feel during my pregnancy, and I blame myself for not following their advice. [A veces me siento presionada por las opiniones de otras personas sobre lo que debería hacer y/o sentir durante mi embarazo, y me culpo por no seguir sus consejos.] | G-SP |

| 12. | I blame myself for not performing at work as I did before because of my pregnancy. [Me culpo por no rendir en el trabajo como antes debido a mi embarazo.] | G-CWR |

| 13. | I feel bad and guilty if I consider taking time off work for my own well-being. [Me siento mal si considero tomar un descanso laboral por mi bienestar.] | G-CWR |

| 14. | I blame myself for not being able to meet all my work responsibilities because of my physical or emotional state. [Me culpo por no poder cumplir con todas mis responsabilidades laborales debido a mi estado físico o emocional.] | G-CWR |

| 15. | I feel guilty when I cannot meet my work goals because of the challenges of pregnancy. [Me siento culpable cuando no puedo cumplir con mis objetivos laborales debido a los desafíos del embarazo.] | G-CWR |

| 16. | Sometimes I feel guilty for not being able to balance my work responsibilities and the demands of pregnancy effectively. [A veces me siento culpable por no poder equilibrar mis responsabilidades laborales y las demandas del embarazo de manera efectiva.] | G-CWR |

| 19-Item Solution | 16-Item Solution (After Removing Low-Loading or Cross-Loading) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | F1 Loadings | F2 Loadings | F3 Loadings | F4 Loadings | R2 | Complexity | F1 Loadings | F2 Loadings | F3 Loadings | F4 Loadings | R2 | Complexity |

| 1 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.24 | −0.12 | 0.59 | 1.29 | 0.98 | −0.13 | 0.06 | −0.17 | 0.71 | 1.10 |

| 2 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.28 | −0.04 | 0.73 | 1.42 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.71 | 1.18 |

| 3 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 1.24 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.60 | 1.13 |

| 4 | 0.06 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 2.09 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.67 | 0.10 | −0.17 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 1.43 | 0.63 | 0.12 | −0.19 | 0.22 | 0.57 | 1.52 |

| 6 | 0.14 | 0.83 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.76 | 1.09 | −0.07 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 1.03 |

| 7 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.79 | 1.24 | 0.15 | 0.79 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.77 | 1.08 |

| 8 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.63 | 1.14 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.64 | 1.03 |

| 9 | 0.10 | 0.88 | −0.15 | −0.10 | 0.68 | 1.12 | −0.09 | 0.93 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.71 | 1.03 |

| 10 | −0.39 | 0.75 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 1.79 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.17 | −0.03 | 0.80 | −0.05 | 0.70 | 1.10 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.72 | −0.01 | 0.66 | 1.07 |

| 12 | 0.15 | −0.11 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.69 | 1.20 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.70 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 1.12 |

| 13 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 1.13 | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 1.05 |

| 14 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 1.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 1.01 |

| 15 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 1.10 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 1.09 |

| 16 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 1.01 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 1.02 |

| 17 | −0.15 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 2.25 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.16 | 0.93 | 0.74 | 1.08 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 1.05 |

| 19 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 1.16 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 1.10 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |||||

| r with F2 | 0.45 | - | - | - | 0.66 | - | - | - | ||||

| r with F3 | 0.42 | 0.52 | - | - | 0.58 | 0.34 | - | - | ||||

| r with F4 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.51 | - | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.65 | - | ||||

| Explained variance | 13% | 19% | 13% | 19% | 15% | 19% | 13% | 23% | ||||

| No previous children (n = 98) | Previous children (n = 73) | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | d | |

| PGAS. G-LSC | 3.18 | 1.38 | 2.85 | 1.33 | 1.6 | 0.111 | 0.25 |

| PGAS. G-UEE | 2.97 | 1.48 | 2.88 | 1.49 | 0.37 | 0.709 | 0.06 |

| PGAS. G-SP | 2.38 | 1.21 | 2.32 | 1.39 | 0.32 | 0.751 | 0.05 |

| PGAS. G-CWR | 2.73 | 1.43 | 2.64 | 1.42 | 0.44 | 0.663 | 0.07 |

| PGAS. Total score | 2.84 | 1.15 | 2.69 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 0.431 | 0.12 |

| Not considered pregnancy termination (n = 118) | Considered pregnancy termination (n = 53) | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | d | |

| PGAS. G-LSC | 2.81 | 1.3 | 3.55 | 1.36 | −3.3 | <0.001 | −0.55 |

| PGAS. G-UEE | 2.51 | 1.35 | 3.87 | 1.33 | −6.13 | <0.001 | −1.00 |

| PGAS. G-SP a | 2.07 | 1.12 | 2.99 | 1.41 | −4.2 | <0.001 | −0.75 |

| PGAS. G-CWR | 2.36 | 1.34 | 3.43 | 1.34 | −4.82 | <0.001 | −0.79 |

| PGAS. Total score | 2.46 | 1.06 | 3.49 | 1.17 | −5.48 | <0.001 | −0.94 |

| Scores Range | M | SD | PGAS. G-LSC | PGAS. G-UEE | PGAS. G-SP | PGAS. G-CWR | PGAS. Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGAS. G-LSC | 1–6 | 3.04 | 1.36 | - | 0.67 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.82 *** |

| PGAS. G-UEE | 1–6 | 2.93 | 1.48 | - | - | 0.66 *** | 0.65 *** | 0.88 *** |

| PGAS. G-SP | 1–6 | 2.36 | 1.29 | - | - | - | 0.65 *** | 0.82 *** |

| PGAS. G-CWR | 1–6 | 2.69 | 1.43 | - | - | - | - | 0.87 *** |

| PGAS. Total score | 1–6 | 2.77 | 1.19 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age | 20–45 | 34.25 | 4.98 | −0.14 | −0.16 * | −0.15 | −0.07 | −0.15 |

| Educational level | 1–7 | 4.99 | 1.10 | 0.25 *** | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.16 * | 0.18 * |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 1–39 | 21.36 | 10.21 | −0.25 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.17 * | −0.33 *** | −0.17 * |

| Time to conception (months) | 0–50 | 7.39 | 9.94 | −0.04 | −0.18 * | −0.06 | −0.088 | −0.11 |

| Hours of sleep | 4–14 | 7.56 | 1.35 | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.16 * | −0.08 | −0.12 |

| Perceived sleep quality | 1–5 | 2.61 | 0.92 | 0.17 * | 0.17 * | 0.064 | 0.14 | 0.17 * |

| Planned pregnancy (no/yes) | 0–1 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Pregnancy complications (no/yes) | 0–1 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.22 ** | 0.17 * | 0.17 * | 0.22 ** | 0.23 ** |

| Dispositional guilt | 5–20 | 12.60 | 3.83 | 0.38 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.47 *** |

| Positive affect | 6–25 | 16.61 | 3.92 | −0.18 * | −0.17 * | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.12 |

| Negative affect | 5–24 | 12.10 | 4.59 | 0.50 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.57 *** |

| Self-esteem | 10–40 | 29.68 | 6.18 | −0.42 *** | −0.53 *** | −0.47 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.53 *** |

| Perceived social support | 12–42 | 32.80 | 6.84 | −0.14 | −0.22 ** | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.18 * |

| Antepartum depression | 10–39 | 20.50 | 6.46 | 0.51 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.60 *** |

| Prenatal distress | 12–50 | 29.77 | 7.58 | 0.55 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.65 *** |

| Antepartum Depression | Prenatal Distress | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | p | Δ Adj. R2 | p | β | p | Δ Adj. R2 | p |

| Step 1 | 0.017 | 0.084 | 0.059 | 0.002 | ||||

| Age | −0.168 | 0.030 | −0.096 | 0.202 | ||||

| Educational level | 0.055 | 0.470 | 0.258 | <0.001 | ||||

| Step 2 | 0.068 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.033 | ||||

| Gestational age | −0.218 | 0.004 | −0.147 | 0.052 | ||||

| Planned pregnancy | −0.057 | 0.446 | 0.035 | 0.639 | ||||

| Pregnancy complications | −0.150 | 0.048 | −0.136 | 0.070 | ||||

| Step 3 | 0.569 | <0.001 | 0.260 | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative affect | 0.786 | <0.001 | 0.534 | <0.001 | ||||

| Step 4 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.273 | ||||

| Perceived social support | −0.192 | <0.001 | −0.071 | 0.273 | ||||

| Step 5 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.148 | <0.001 | ||||

| PGAS. G-LSC | 0.004 | 0.952 | 0.061 | 0.453 | ||||

| PGAS. G-UEE | 0.213 | 0.002 | 0.175 | 0.055 | ||||

| PGAS. G-SP | 0.103 | 0.102 | 0.303 | <0.001 | ||||

| PGAS. G-CWR | −0.090 | 0.132 | 0.017 | 0.829 | ||||

| Total adjusted R2 | 0.722 | 0.500 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luque-Reca, O.; Peñacoba, C.; Catalá, P. Development and Validation of the Pregnancy Guilt Assessment Scale (PGAS): A Specific Tool for Assessing Guilt in Pregnancy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243241

Luque-Reca O, Peñacoba C, Catalá P. Development and Validation of the Pregnancy Guilt Assessment Scale (PGAS): A Specific Tool for Assessing Guilt in Pregnancy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243241

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuque-Reca, Octavio, Cecilia Peñacoba, and Patricia Catalá. 2025. "Development and Validation of the Pregnancy Guilt Assessment Scale (PGAS): A Specific Tool for Assessing Guilt in Pregnancy" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243241

APA StyleLuque-Reca, O., Peñacoba, C., & Catalá, P. (2025). Development and Validation of the Pregnancy Guilt Assessment Scale (PGAS): A Specific Tool for Assessing Guilt in Pregnancy. Healthcare, 13(24), 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243241