Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Data Sources and Searches

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Study Design

2.3.2. Population

2.3.3. Interventions

2.3.4. Comparators

2.3.5. Outcome Measures

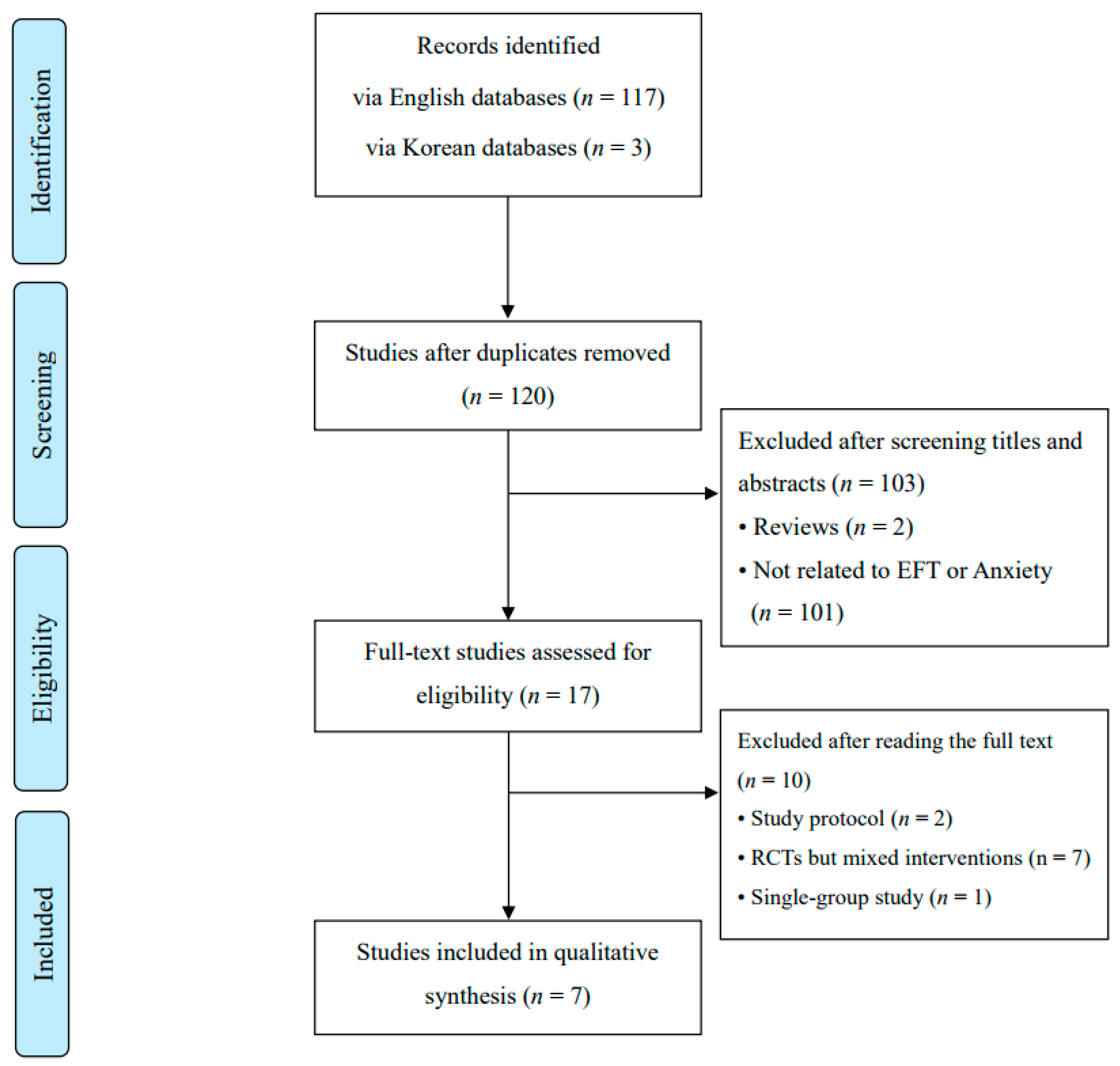

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction Process

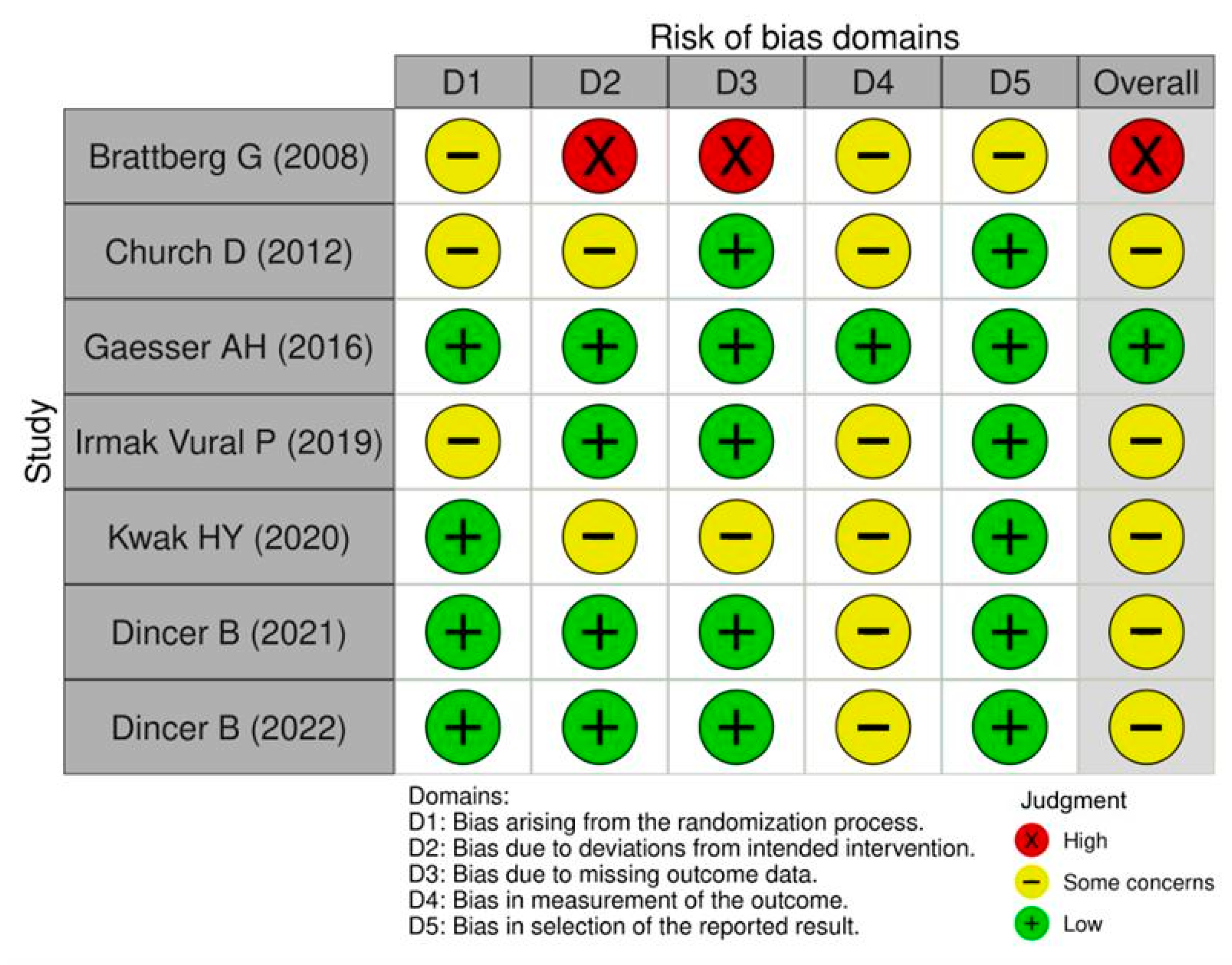

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Participants

3.3. EFT Interventions

3.4. Control Interventions

3.5. Effects of EFT

3.5.1. Primary Outcome

Anxiety Outcome

3.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

Psychological Indicators (Depression and Anger)

Self-Efficacy

Cortisol Levels

Quality of Life

Adverse Events

3.6. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Implications

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

4.3. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clond, M. Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, S.F.; Hashim, I.J.; Hashim, M.J.; Stip, E.; Samad, M.A.; Al Ahbabi, A. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders: Global Burden and Sociodemographic Associations. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.J.; Scott, K.M.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Global Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino, F.M.; da Silva, C.N.; Jerônimo, J.S.; Mulling, E.S.; da Cunha, L.L.; Weymar, M.K.; Alt, R.; Caputo, E.L.; Feter, N. Prevalence of Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of over 2 Million People. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 318, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Stein, M.B.; Eley, T.C.; Milad, M.R.; Holmes, A.; Rapee, R.M.; Wittchen, H.-U. Anxiety Disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.B.; Kirst, N.; Shultz, C.G. Diagnosis and Management of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 91, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Simon, N.M. Anxiety Disorders: A Review. JAMA 2022, 328, 2431–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, T.C.; Stamatakis, E.; Hamer, M.; Starr, J.M.; Kivimäki, M.; Batty, G.D. Association between psychological distress and mortality: Individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2012, 345, e4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubovski, E.; Johnson, J.A.; Nasir, M.; Müller-Vahl, K.; Bloch, M.H. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Dose-Response Curve of SSRIs and SNRIs in Anxiety Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, J.K.; Andrews, L.A.; Witcraft, S.M.; Powers, M.B.; Smits, J.A.J.; Hofmann, S.G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety and Related Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollon, P. Psychoanalytic Energy Psychotherapy; Karnac Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Vasudevan, A.; O’Keefe, T. Clinical EFT as an Evidence-Based Practice for the Treatment of Psychological and Physiological Conditions: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.; Groesbeck, G.; Stapleton, P.; Sims, R.; Blickheuser, K.; Church, D. Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) Improves Multiple Physiological Markers of Health. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2019, 24, 2515690X18823691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelms, J.A.; Castel, L. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized and Nonrandomized Trials of Clinical Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) for the Treatment of Depression. Explore 2016, 12, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Vasudevan, A.; De Foe, A.; Lovegrove, R. Money Attitudes after Clinical Emotional Freedom Techniques: Psychological Change in a Virtual vs In-Person Group. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2023, 37, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, B.; Nelms, J. The Effectiveness of Emotional Freedom Techniques in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Explore 2017, 13, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association; DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, G. The EFT Manual, 2nd ed.; Energy Psychology Press: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattberg, G. Self-Administered EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) in Individuals with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Trial. Integr. Med. 2008, 7, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Church, D.; Yount, G.; Brooks, A.J. The Effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on Stress Biochemistry: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012, 200, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaesser, A.H.; Karan, O.C. A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Emotional Freedom Technique and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy to Reduce Adolescent Anxiety: A Pilot Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak Vural, P.; Aslan, E. Emotional Freedom Techniques and Breathing Awareness to Reduce Childbirth Fear: A Randomized Controlled Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 35, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.Y.; Choi, E.J.; Kim, J.W.; Suh, H.W.; Chung, S.Y. Effect of the Emotional Freedom Techniques on Anger Symptoms in Hwabyung Patients: A Comparison with the Progressive Muscle Relaxation Technique in a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Explore 2020, 16, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B.; Inangil, D. The Effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on Nurses’ Stress, Anxiety, and Burnout Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Explore 2021, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dincer, B.; Özçelik, S.K.; Özer, Z.; Bahçecik, N. Breathing Therapy and Emotional Freedom Techniques on Public Speaking Anxiety in Turkish Nursing Students: A Randomized Controlled Study. Explore 2022, 18, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munder, T.; Barth, J. Cochrane’s Risk of Bias Tool in the Context of Psychotherapy Outcome Research. Psychother. Res. 2018, 28, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Mollon, P.; Feinstein, D.; Boath, E.; Mackay, D.; Sims, R. Guidelines for the Treatment of PTSD Using Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques). Healthcare 2018, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Choi, Y.E.; Kwon, O.; Kwon, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, H. Emotional Freedom Technique versus Written Exposure Therapy versus Waiting List for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Protocol for a Randomised Clinical MRI Study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.S.; Soumerai, S.B.; Lomas, J.; Ross-Degnan, D. Evidence of Self-Report Bias in Assessing Adherence to Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1999, 11, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hek, K.; Direk, N.; Newson, R.S.; Hofman, A.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Mulder, C.L.; Tiemeier, H. Anxiety Disorders and Salivary Cortisol Levels in Older Adults: A Population-Based Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łoś, K.; Waszkiewicz, N. Biological Markers in Anxiety Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Pieh, C.; Probst, T. Metabolomic Biomarkers in Anxiety Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Jain, A.; Gautam, M.; Vahia, V.N.; Gautam, A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Panic Disorder (PD). Indian J. Psychiatry 2017, 59 (Suppl. 1), S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunan, M.B.; Suwarni, L.; Setiawati, L.; Mardjan, M. EFT (Emotional Freedom Technique) as an Alternative Therapy to Reduce Anxiety Disorders and Depression in People Who Are Positive for COVID-19. J. Psiko. Stud. 2022, 11, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, M.; Sunder, G.; Kadam, S.; Abhyankar, A. A Perspective on Digital Health Platform Design and Its Implementation at National Level. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1260855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Lam, S.U.; Simonsson, O.; Torous, J.; Sun, S. Mobile Phone-Based Interventions for Mental Health: A Systematic Meta-Review of 14 Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLOS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Sabot, D. App-Based Delivery of Clinical Emotional Freedom Techniques: Cross-Sectional Study of App User Self-Ratings. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author (Year) Country | Patients’ Disease, Gender (M/F), Age (M ± SD), Sample Size (Randomized/Analyzed) | EFT Intervention | Control Intervention | Outcome Measurements | Main Results (Between-Group Difference, Mean ± SD) | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brattberg G (2008) Sweden [21] | Fibromyalgia women with anxiety Gender: 0/62 Age: 43.8 ± 8.8 Sample: 86/62 | EFT, n = 26, total 56 sessions (once a day for 8 weeks) | No intervention, n = 36 |

| 1.

| (E) No AEs occurred (C) No AEs occurred |

| Church D (2012) United States [22] | Non-clinical people with anxiety Gender: 17/66 Age: 51.3 ± 12.02 Sample: 83/83 | EFT (n = 28), total 1 session | (C1) Supportive interviews, n= 28, total 1 session (C2) No intervention, n = 27 |

| 1.

| n.r. |

| Gaesser AH (2016) United States [23] | Students with anxiety Gender: 18/45 Age: 10–18 Sample: 63/62 | (E) EFT, n = 20, total 3 sessions (5 months) | (C1) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, n = 21, total 3 sessions (5 months) (C2) No intervention, n = 21 |

|

(E vs C2) p < 0.01, (C1 vs C2) NS (p = 0.12) | (E) No AEs occurred (C) No AEs occurred |

| Irmak Vural P (2019) Turkey [24] | Pregnant women with anxiety Gender: 0/120 Age: (E) 27.29 ± 3.97 (C1) 27.51 ± 4.65 (C2) 27.36 ± 4.19 Sample: 120/120 | (E) EFT (n = 35), total 9 sessions (latent phase; the intervention was delivered three times during each of the active and transition phases) | (C1) Breathing Therapy (n = 35), total sessions: n.r. (The intervention was administered as needed whenever uterine contractions occurred) (C2) No intervention (n = 50) |

| 1.

| n.r. |

| Kwak HY (2020) South Korea [25] | Hwabyung * patients with anxiety Gender: 3/28 Age: (E)50 ± 13.31, (C)49.67 ± 12.20 sample: 40/31 | EFT, n = 15, total 4 sessions (once a week for 4 weeks) | Progressive muscle relaxation, n =16, total 4 sessions (once a week for 4 weeks) |

| 1.

| (E) No AEs occurred (C) No AEs occurred |

| Dincer B (2021) Turkey [26] | Nurses with anxiety Gender: 8/64 Age: 33.45 ± 9.63 Sample: 80/72 | EFT (n = 35), total 1 session | No intervention (n = 37) |

| 1.

| n.r. |

| Dincer B (2022) Turkey [27] | Students with anxiety Gender: 8/68 Age: 20.36 ± 0.81 Sample: 78/76 | EFT (n = 25), total 1 session | (C1) Breathing Therapy (n = 26), total 1 session (C2) No intervention (n = 25) |

| 1.

| n.r. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, S.H.; Sung, S.-H.; Lee, G. Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172180

Choi SH, Sung S-H, Lee G. Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172180

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Seong Hun, Soo-Hyun Sung, and Gihyun Lee. 2025. "Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172180

APA StyleChoi, S. H., Sung, S.-H., & Lee, G. (2025). Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(17), 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172180