Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor for Visuospatial Ability in Healthy Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Apparatus and Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire

2.4.2. Neuropsychological Tests

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Control Task

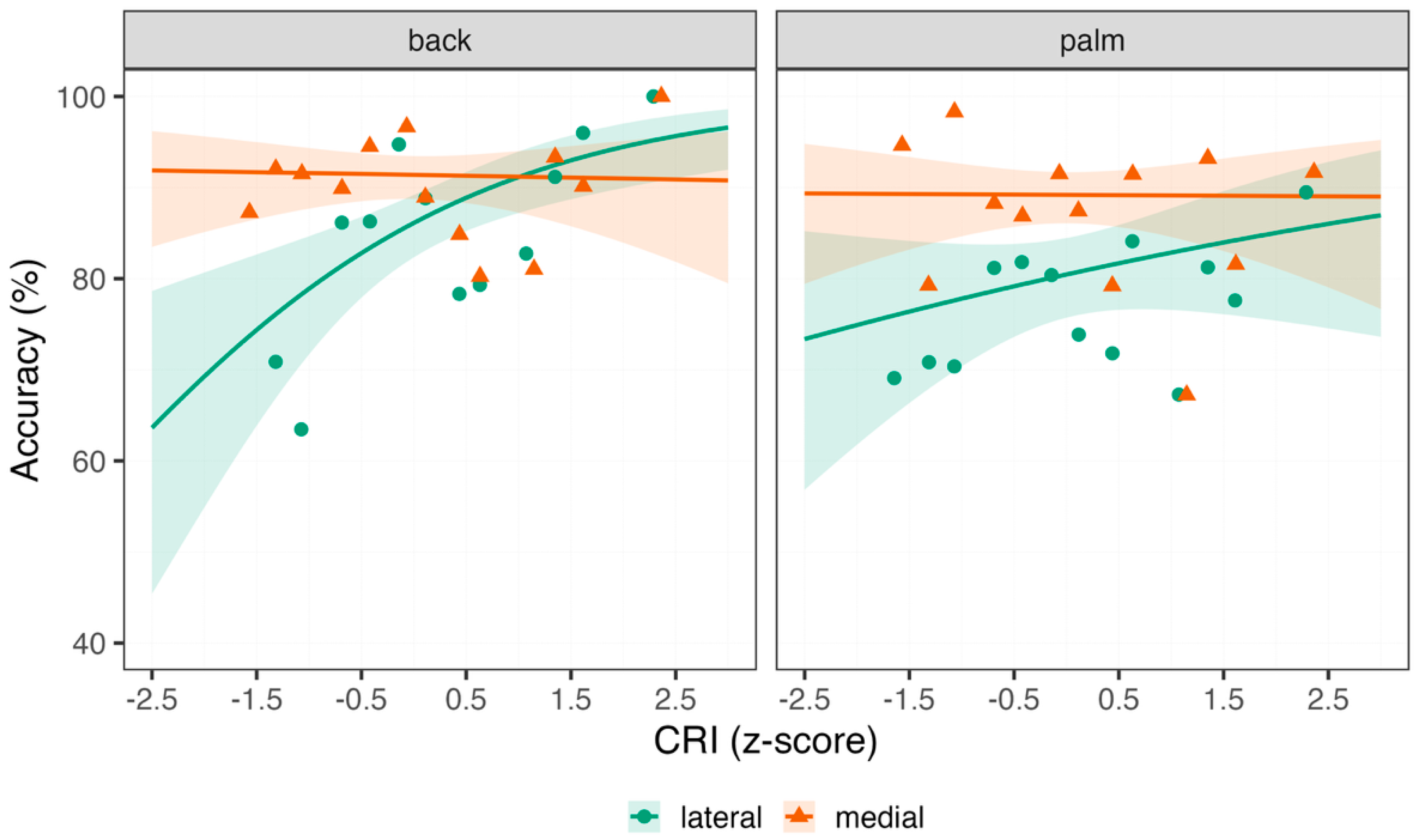

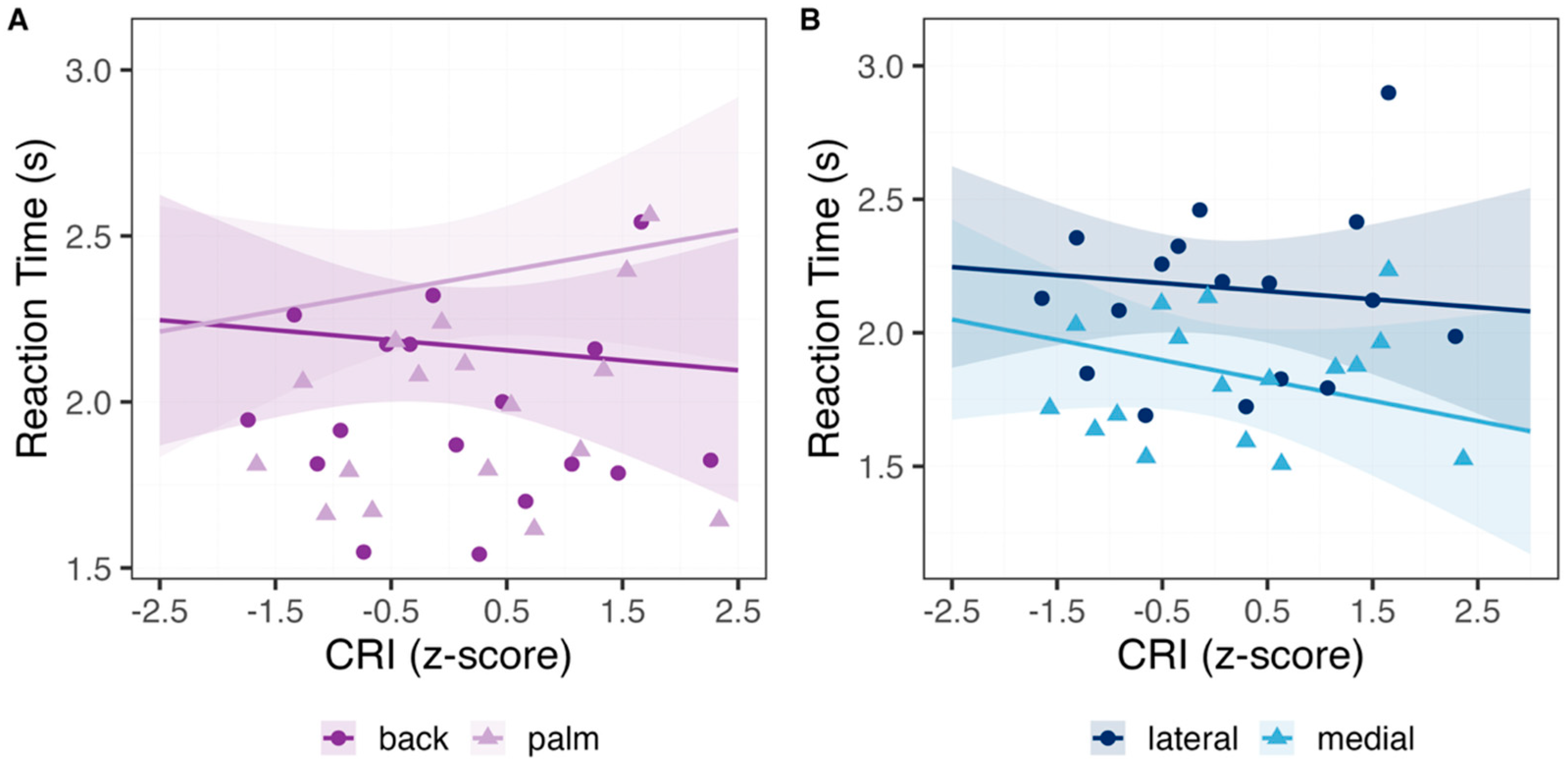

3.2. Hand Laterality Task

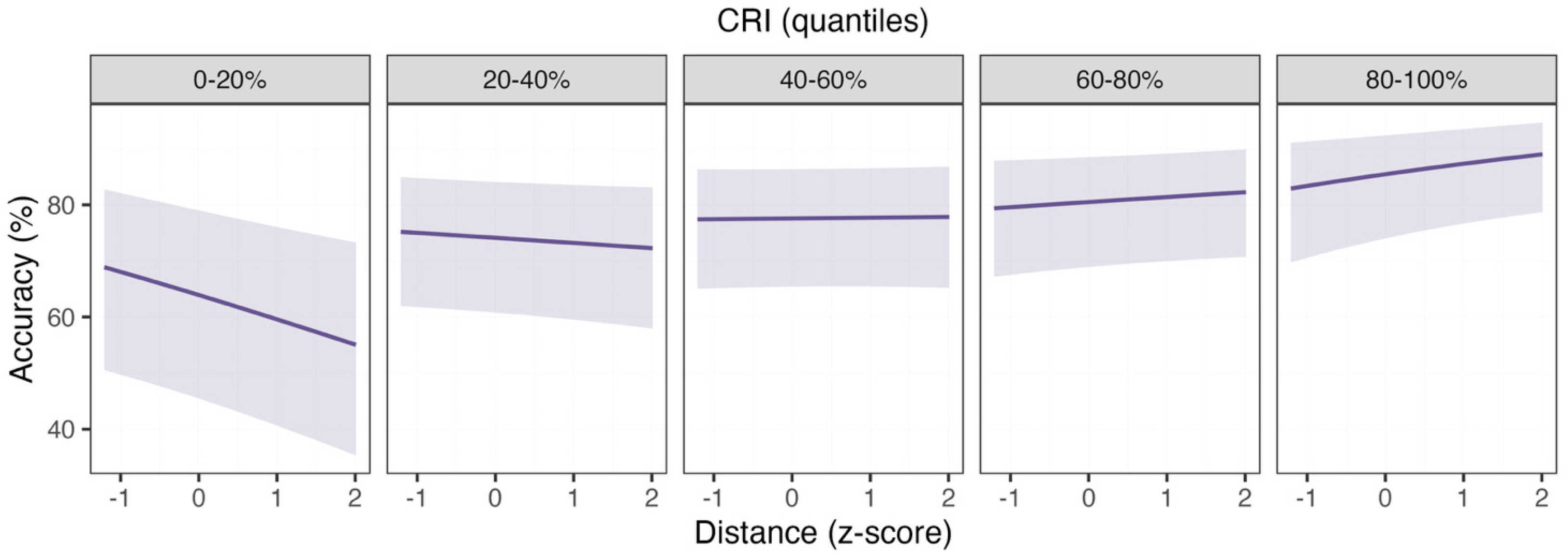

3.3. Letter Congruency Task

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

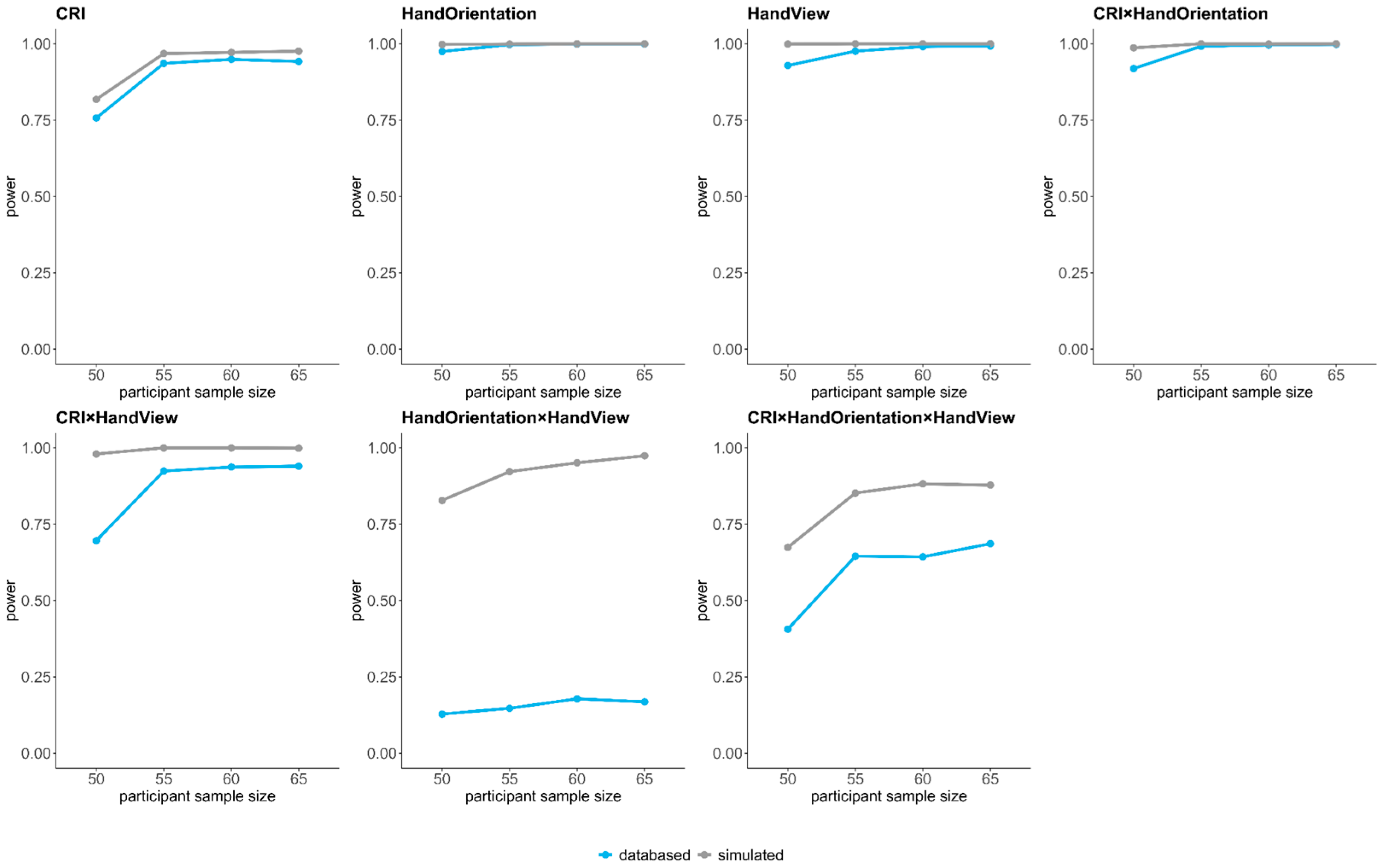

Appendix A.1. Post Hoc Simulation Based on Generalized-Linear Mixed Effect Models to Estimate Power Given Different Sample Sizes

| Predictors | Type | N = 50 | N = 55 | N = 60 | N = 65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRI | databased | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Hand Orientation | databased | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hand View | databased | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| CRI × Hand Orientation | databased | 0.92 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 |

| CRI × Hand View | databased | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Hand Orientation x Hand View | databased | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| CRI × Hand Orientation × Hand View | databased | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| CRI | simulated | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Hand Orientation | simulated | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hand View | simulated | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CRI × Hand Orientation | simulated | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CRI × Hand View | simulated | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hand Orientation × Hand View | simulated | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| CRI × Hand Orientation × Hand View | simulated | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

Appendix A.2. Participant’s Descriptive Demographic and Neuropsychological Tests Score

| Variable | Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 67.16 ± 7.34 |

| Sex | 23 M (36 F) |

| Criq (total) | 134.72 ± 14.06 |

| CRIq (education) | 115.34 ± 12.49 |

| CRIq (working activity) | 117.33 ± 17.46 |

| CRIq (leisure time activities) | 148.24 ± 18.96 |

| MoCA | 25.55 ± 2.09 |

| CPM | 32.28 ± 3.02 |

| TMT | 56.81 ± 33.29 |

| Digit Span Forward | 5 ± 1.1 |

| Digit Span Backward | 3 ± 1.02 |

References

- Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hou, W.; Li, H. Cognitive Decline Associated with Aging. In Cognitive Aging and Brain Health; Zhang, Z., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P. The adaptive brain: Aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Selective review of cognitive aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deary, I.J.; Corley, J.; Gow, A.J.; Harris, S.E.; Houlihan, L.M.; Marioni, R.E.; Penke, L.; Rafnsson, S.B.; Starr, J.M. Age-associated cognitive decline. Br. Med. Bull. 2009, 92, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedden, T.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Insights into the ageing mind: A view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salthouse, T.A. Influence of age on practice effects in longitudinal neurocognitive change. Neuropsychology 2010, 24, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Bach, J.; Evans, D.A.; Bennett, D.A. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A.; Ferrer-Caja, E. What needs to be explained to account for age-related effects on multiple cognitive variables? Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daselaar, S.; Dennis, N.A.; Cabeza, R. Ageing: Age-related changes in episodic and working memory. In Clinical Applications of Functional Brain MRI; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hinault, T.; Lemaire, P. Aging effects on brain and cognition: What do we learn from a strategy perspective? In The Cambridge Handbook of Cognitive Aging: A Life Course Perspective; Thomas, A.K., Gutchess, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borella, E.; Meneghetti, C.; Ronconi, L.; De Beni, R. Spatial abilities across the adult life span. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, N.; Bryant, D.C.; MacLean, J.N.; Gonzalez, C.L.R. Assessing visuospatial abilities in healthy aging: A novel visuomotor task. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Ying, H.; Liu, Y. Corrigendum: Vestibular dysfunction is an important contributor to the aging of visuospatial ability in older adults–Data from a computerized test system. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1166687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, R.N.; Metzler, J. Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science 1971, 171, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacks, J.M. Neuroimaging studies of mental rotation: A meta-analysis and review. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2008, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, K.; Heinze, H.-J.; Lutz, K.; Kanowski, M.; Jäncke, L. Cortical activations during the mental rotation of different visual objects. NeuroImage 2001, 13, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milivojevic, B.; Hamm, J.P.; Corballis, M.C. Functional neuroanatomy of mental rotation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2009, 21, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.M. Imagined spatial transformation of one’s body. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1987, 116, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.M. Temporal and kinematic properties of motor behavior reflected in mentally simulated action. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1994, 20, 709–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneiser, J.; Jahn, G.; Grothe, M.; Lotze, M. From visual to motor strategies: Training in mental rotation of hands. NeuroImage 2018, 167, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyek, N.; Di Rienzo, F.; Collet, C.; Creveaux, T.; Guillot, A. Hand mental rotation is not systematically altered by actual body position: Laterality judgment versus same–different comparison tasks. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2014, 76, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumiati, R.I.; Tomasino, B.; Vorano, L.; Umiltà, C.; De Luca, G. Selective Deficit of Imagining Finger Configurations. Cortex 2001, 37, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasino, B.; Toraldo, A.; Rumiati, R.I. Dissociation between the mental rotation of visual images and motor images in unilateral brain-damaged patients. Brain Cogn. 2003, 51, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, A.L.; Wilson, P.H. Adult age differences in the ability to mentally transform object and body stimuli. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2010, 17, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sang, L.; Li, P.; Yan, R.; Qiu, M.; Liu, C. Aging changes effective connectivity of motor networks during motor execution and motor imagery. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimpont, A.; Pozzo, T.; Papaxanthis, C. Aging affects the mental rotation of left and right hands. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, L.; Tomasino, B.; Marusic, N.; Eleopra, R.; Rumiati, R.I. The effects of healthy aging on mental imagery as revealed by egocentric and allocentric mental spatial transformations. Acta Psychol. 2013, 143, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasino, B.; Rumiati, R.I. Effects of strategies on mental rotation and hemispheric lateralization: Neuropsychological evidence. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Della Sala, S.; Gherri, E. Age-associated delay in mental rotation. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, I.; Takeda, K.; Harada, Y.; Mochizuki, H.; Shimoda, N. Age-related differences in strategy in the hand mental rotation task. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 615584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002, 8, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive Reserve and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Arenaza-Urquiljo, E.M.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Belleville, S.; Cantillon, M.; Chetelat, G.; Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Kempermann, G.; Kremen, W.S.; et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmeas, N.; Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve: Implications for diagnosis and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2004, 4, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldan, A.; Pettigrew, C.; Albert, M. Cognitive reserve from the perspective of preclinical Alzheimer disease. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 36, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Yu, L.; Lamar, M.; Schneider, J.A.; Boyle, P.A.; Bennett, D.A. Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology 2019, 92, e1041–e1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andel, R.; Silverstein, M.; Kåreholt, I. The role of midlife occupational complexity and leisure activity in late-life cognition. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2015, 70, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.L.; Gibbons, L.E.; Rentz, D.M.; Carvalho, J.O.; Manly, J.; Bennett, D.A.; Jones, R.N. A life course model of cognitive activities, socioeconomic status, education, reading ability, and cognition. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.E.; Jester, D.J.; Petkus, A.J.; Andel, R. Cognitive reserve, Alzheimer’s neuropathology, and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2021, 31, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.L.; Sajjad, A.; Bramer, W.M.; Ikram, M.A.; Tiemeier, H.; Stephan, B.C.M. Exploring strategies to operationalize cognitive reserve: A systematic review of reviews. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2015, 37, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdebeeck, C.; Martyr, A.; Clare, L. Cognitive reserve and cognitive function in healthy older people: A meta-analysis. Aging, Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2016, 23, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.J.; Bates, T.C.; Deary, I.J. Is education associated with improvements in general cognitive ability, or in specific skills? Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Tapia, L.; García, J.; Cánovas, R.; León, I. Cognitive reserve, age, and their relation to attentional and executive functions. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2012, 19, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker-Drob, E.M.; Johnson, K.E.; Jones, R.N. The cognitive reserve hypothesis: A longitudinal examination of age-associated declines in reasoning and processing speed. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, C.; Soldan, A. Defining cognitive reserve and implications for cognitive aging. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauti, M.; Monachesi, B.; Taccari, G.; Rumiati, R.I. Facing healthy and pathological aging: A systematic review of fMRI task-based studies to understand the neural mechanisms of cognitive reserve. Brain Cogn. 2024, 182, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Barnes, C.A.; Grady, C.; Jones, R.N.; Raz, N. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: Operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 83, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, V.; Hidalgo, V.; Salvador, A. Linking cognitive reserve to neuropsychological outcomes and resting-state frequency bands in healthy aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1540168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.; Kaltner, S. Object-based and egocentric mental rotation performance in older adults: The importance of gender differences and motor ability. Aging, Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2014, 21, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumle, L.; Võ, M.L.-H.; Draschkow, D. DejanDraschkow/Mixedpower, Version v1.0; Mixedpower: A Library for Estimating Simulation-Based Power for Mixed Models in R; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, J.; Grapsas, S.; Poorthuis, A.M.G.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Thomaes, S. Coming of age in a warming world: A self-determination theory perspective. Child Dev. Perspect. 2025, 19, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, R.C.; Weigard, A.S.; Sripada, C.; Jonides, J.; Klump, K.L.; Burt, S.A.; Hyde, L.W. Efficiency of evidence accumulation as a formal model-based measure of task-general executive functioning in adolescents. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2025, 134, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameira, A.P.; Guimarães-Silva, S.; Werneck-Galvão, C.; Junior, A.P.; Gawryszewski, L.G. Recognition of hand shape drawings on vertical and horizontal display. Psychol. Neurosci. 2008, 1, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.D.; Stankov, L. Age differences in the realism of confidence judgements: A calibration study using tests of fluid and crystallized intelligence. Learn. Individ. Differ. 1996, 8, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The montreal cognitive assessment, moca: A brief screening tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.; Raven, J.C.; Court, J.H. Raven Manual: Section 4, Advanced Progressive Matrices, 1998 ed.; Oxford Psychologists Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised: Manual; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, R. Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R.; Davidson, D.; Bates, D. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.C.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.J.; Levy, R.; Scheepers, C.; Tily, H.J. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 2013, 68, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuschek, H.; Kliegl, R.; Vasishth, S.; Baayen, H.; Bates, D. Balancing Type I error and power in linear mixed models. J. Mem. Lang. 2017, 94, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, S.G. Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satterthwaite, F.E. An approximate distribution of estimates of variance components. Biom. Bull. 1946, 2, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V.; Piaskowski, J.; Banfai, B.; Bolker, B.; Buerkner, P.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Hervé, M.; Jung, M.; Love, J.; Miguez, F.; et al. Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/emmeans.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Malinowski, J.C. Mental rotation and real-world wayfinding. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2001, 92, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saariluoma, P. Visuo-spatial interference and apperception in chess. In Advances in Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 80, pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, R.; Reiner, M. Shared mechanisms underlie mental imagery and motor planning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G.; Braithwaite, F.A.; Edwards, L.M.; Causby, R.S.; Conson, M.; Stanton, T.R. The effect of handedness on mental rotation of hands: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Res. 2021, 85, 2829–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenmolen, N.L.; Overdorp, E.J.; Fasotti, L.; Claassen, J.A.; Kessels, R.P.; Oosterman, J.M. Memory Strategy Training in Older Adults with Subjective Memory Complaints: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2018, 24, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.J.; Bates, T.C.; Der, G.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. Education is associated with higher later life IQ scores, but not with faster cognitive processing speed. Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.; Johnson, B.W.; Corballis, M.C. One good turn deserves another: An event-related brain potential study of rotated mirror–normal letter discriminations. Neuropsychologia 2004, 42, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Peña, M.I.; Aznar-Casanova, J.A. Mental rotation of mirrored letters: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Brain Cogn. 2009, 69, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.A.; Shepard, R.N. Chronometric Studies of the Rotation of Mental Images. In Visual Information Processing; Chase, W.G., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankaoua, M.; Luria, R. One turn at a time: Behavioral and ERP evidence for two types of rotations in the classical mental rotation task. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Li, C.; Xue, J.; Yue, J.; Zhang, C. Mirror-normal difference in the late phase of mental rotation: An ERP study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schiff, S.; Amodio, P.; Bisiacchi, P. The effect of age, educational level, gender and cognitive reserve on visuospatial working memory performance across adult life span. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2020, 27, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhuis, E.J.; Slade, K.; Smith, E.; May, P.J.C.; Nuttall, H.E. Getting the brain into gear: An online study investigating cognitive reserve and word-finding abilities in healthy ageing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, D.J.; Bennett, I.J.; Song, A.W. Cerebral white matter integrity and cognitive aging: Contributions from diffusion tensor imaging. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2009, 19, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrencic, L.M.; Churches, O.F.; Keage, H.A.D. Cognitive reserve is not associated with improved performance in all cognitive domains. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2018, 25, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.; O’Leary, E. Depression, cognitive reserve and memory performance in older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-P. Classification of cognitive reserve in healthy older adults based on brain activity using support vector machine. Physiol. Meas. 2020, 41, 065009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, N.; Monaco, M.R.L.; Fusco, D.; Vetrano, D.L.; Zuccalà, G.; Bernabei, R.; Brandi, V.; Pisciotta, M.S.; Silveri, M.C. The role of cognitive reserve in cognitive aging: What we can learn from Parkinson’s disease. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 877–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Amenedo, E.; Sanchez, J.L.; Diaz, F. Cognitive reserve, age, and neuropsychological performance in healthy participants. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2006, 29, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiaco, F.; Iannuzzo, F.; Genovese, G.; Lombardo, C.; Silvestri, M.C.; Celebre, L.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A. Cognitive effects of brief and intensive neurofeedback treatment in schizophrenia: A single center pilot study. AIMS Neurosci. 2024, 11, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barulli, D.; Stern, Y. Efficiency, capacity, compensation, maintenance, plasticity: Emerging concepts in cognitive reserve. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suemoto, C.K.; Bertola, L.; Grinberg, L.T.; Leite, R.E.P.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Santana, P.H.; Pasqualucci, C.A.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Nitrini, R. Education, but not occupation, is associated with cognitive impairment: The role of cognitive reserve in a sample from a low-to-middle-income country. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, S.; Rumiati, R.I.; Pucci, V.; Nucci, M.; Mondini, S. Cognitive reserve can impact trajectories in ageing: A longitudinal study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, P.; Contador, I.; Stern, Y.; Fernandez-Calvo, B.; Sánchez, A.; Ramos, F. Influence of cognitive reserve in schizophrenia: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Huang, C.-M.; Fan, Y.-T.; Liu, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Lee, T.M.-C.; Lee, S.-H. Cognitive Reserve Moderates Effects of White Matter Hyperintensity on Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Function in Late-Life Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, J.A.; Cañadas-Pérez, F.; García-García, J.; Roldan-Tapia, M.D. Cognitive Reserve and Anxiety Interactions Play a Fundamental Role in the Response to the Stress. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Gallén, S.; Soler, M.D.; Albu, S.; Pachón-García, C.; Alviárez-Schulze, V.; Solana-Sánchez, J.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Tormos, J.M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Cattaneo, G. Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor of Mental Health in Middle-Aged Adults Affected by Chronic Pain. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 752623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Gallucci, M.; Costantini, G. A practical primer to power analysis for simple experimental designs. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumle, L.; Võ, M.L.-H.; Draschkow, D. Estimating power in (generalized) linear mixed models: An open introduction and tutorial in R. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 2528–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Predictor | β | SE | CI (2.5%; 97.5%) | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.83 | 0.15 | 1.54; 2.11 | 12.5 | <0.001 |

| CRI | 0.51 | 0.14 | 0.22; 0.79 | 3.53 | <0.001 |

| Medial | 0.54 | 0.11 | 0.32; 0.76 | 4.75 | <0.001 |

| Palm | −0.41 | 0.1 | −0.61; −0.21 | −4.06 | <0.001 |

| CRI × Medial | −0.53 | 0.11 | −0.75; −0.31 | −4.68 | <0.001 |

| CRI × Palm | −0.35 | 0.1 | −0.54; −0.15 | −3.54 | <0.001 |

| Medial × Palm | 0.16 | 0.15 | −0.14; 0.46 | 1.03 | 0.3 |

| CRI × Medial × Palm | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.07; 0.66 | 2.39 | 0.02 |

| Predictor | β | SE | CI (2.5%; 97.5%) | t-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.17 | 0.09 | 1.99; 2.35 | 24.19 | <0.001 |

| CRI | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.17; 0.11 | −0.43 | 0.67 |

| Medial | −0.31 | 0.04 | −0.38; −0.24 | −8.86 | <0.001 |

| Male | −0.23 | 0.15 | −0.51; 0.06 | −1.53 | 0.13 |

| Palm | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.12; 0.27 | 5.24 | <0.001 |

| CRI × Palm | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05; 0.13 | 4.05 | <0.001 |

| Medial × Male | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.09; 0.27 | 3.85 | <0.001 |

| Medial × Palm | −0.19 | 0.04 | −0.28; −0.11 | −4.39 | <0.001 |

| Male × Palm | −0.19 | 0.05 | −0.28; −0.1 | −4.05 | <0.001 |

| CRI × Medial | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.09; −0.00 | −2.03 | 0.04 |

| Predictor | β | SE | CI (2.5%; 97.5%) | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.25 | 0.31 | 0.65; 1.86 | 4.06 | <0.001 |

| Distance | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07; 0.1 | 0.24 | 0.81 |

| Mirror | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.39; 0.61 | 9.06 | <0.001 |

| CRI | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.1; 0.6 | 2.75 | 0.006 |

| Male | −0.03 | 0.2 | −0.42; 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.9 |

| Distance × Mirror | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.02; 0.23 | 2.29 | 0.02 |

| Distance × CRI | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.03; 0.17 | 2.85 | 0.004 |

| Mirror × CRI | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.17; 0.03 | −1.34 | 0.18 |

| Distance × Male | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.05; 0.17 | 1.09 | 0.28 |

| CRI × Male | −0.2 | 0.19 | −0.58; 0.18 | −1.04 | 0.3 |

| Distance × CRI × Male | −0.1 | 0.05 | −0.21; 0.00 | −1.91 | 0.06 |

| Predictor | β | SE | CI (2.5%; 97.5%) | t-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.25 | 0.14 | 1.98; 2.51 | 16.49 | <0.001 |

| Distance | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06; −0.00 | −2.12 | 0.03 |

| Mirror | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.24; 0.32 | 13.48 | <0.001 |

| CRI | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.21; 0.1 | −0.69 | 0.49 |

| Distance × Mirror | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.12; −0.04 | −4.12 | <0.001 |

| Distance × CRI | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04; 0.00 | −1.68 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauti, M.; Allegretti, E.; Rumiati, R.I. Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor for Visuospatial Ability in Healthy Aging. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233162

Mauti M, Allegretti E, Rumiati RI. Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor for Visuospatial Ability in Healthy Aging. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233162

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauti, Marika, Elena Allegretti, and Raffaella I. Rumiati. 2025. "Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor for Visuospatial Ability in Healthy Aging" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233162

APA StyleMauti, M., Allegretti, E., & Rumiati, R. I. (2025). Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor for Visuospatial Ability in Healthy Aging. Healthcare, 13(23), 3162. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233162