Perception Versus Actual Weight: Body Image Dissatisfaction as a Stronger Correlate of Anxiety and Depression than BMI Among Romanian Health Sciences Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To investigate the relationship between subjective body image concerns (measured with EDE-Q), objective body size (BMI), and symptoms of anxiety and depression (measured with HADS) in a sample of Romanian health sciences students.

- To test the hypothesis that subjective body image concerns are more strongly associated with anxiety and depression than is BMI.

- To explore potential differences in these variables between medical and nursing students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Study Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

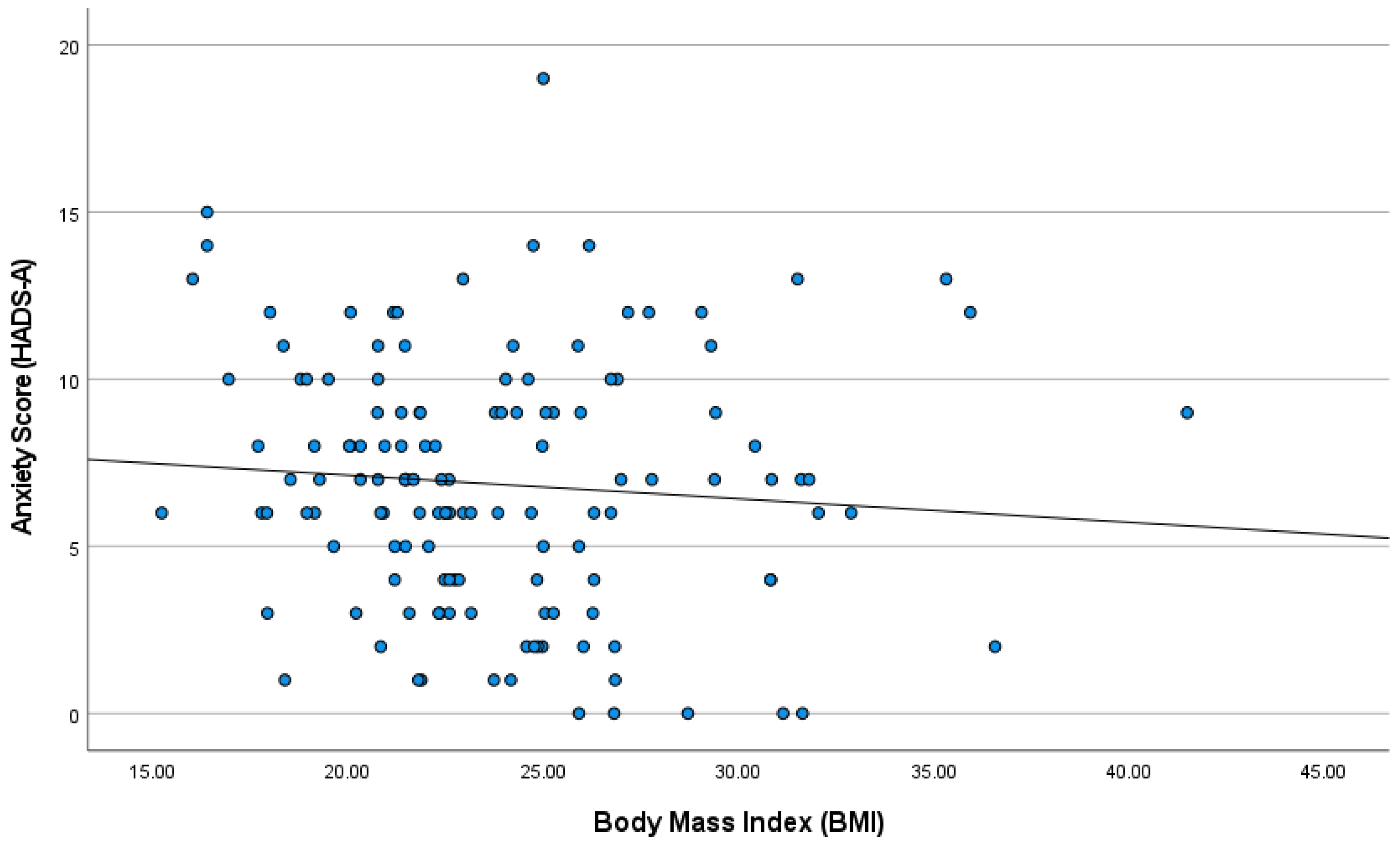

3.2. Correlations Between Body Image, BMI, and Psychological Distress

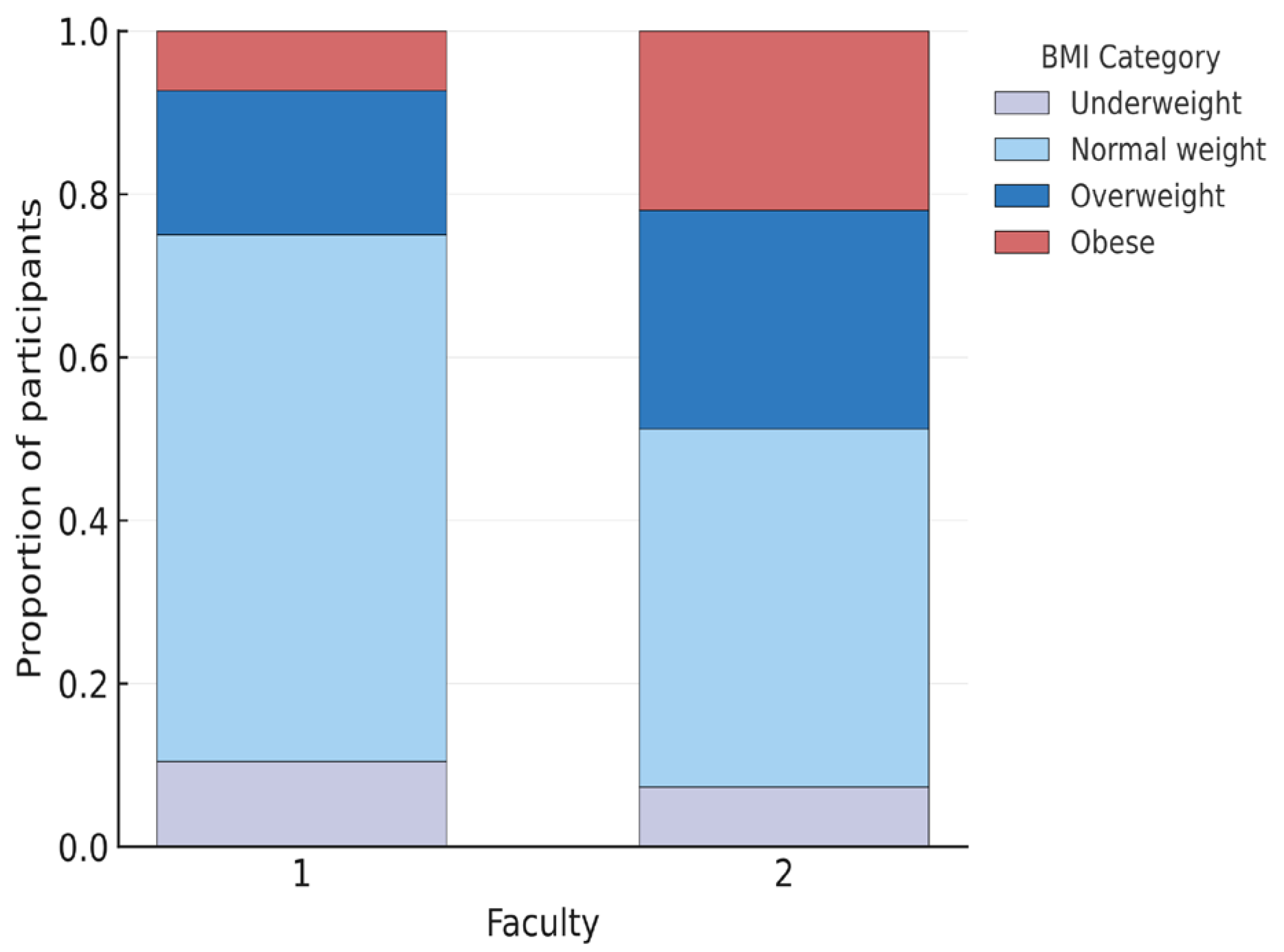

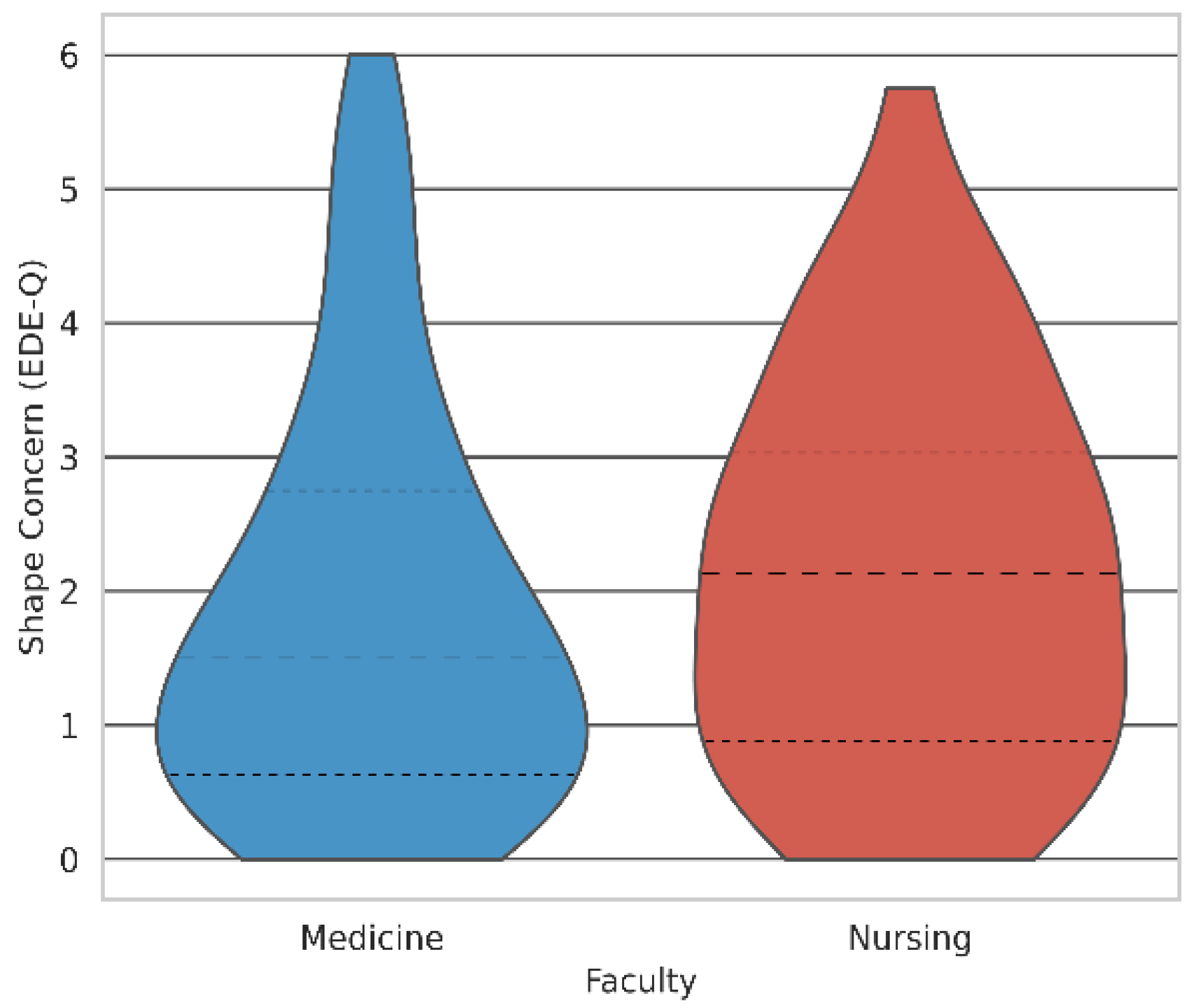

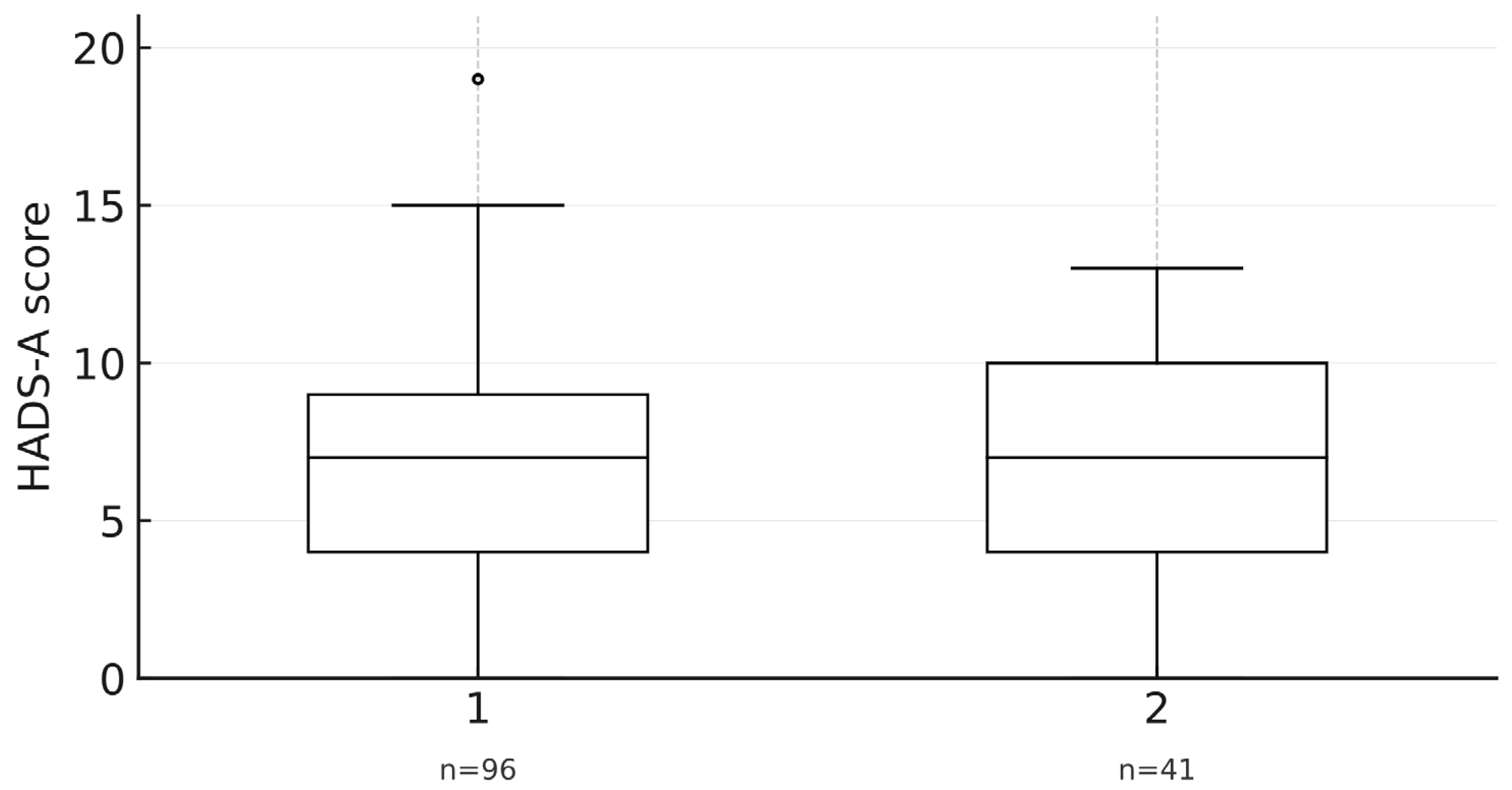

3.3. Descriptive Statistics for Medicine and Nursing Students

3.4. Group Comparisons Between Medicine and Nursing Students

4. Discussion

4.1. The Primacy of Perception in the Context of Global Literature

4.2. Regional Novelty: Body Image in the Eastern European Context

4.3. Implications for University Mental Health in Romania

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Future Research Directions and Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Zeng, N.; Liu, Y.; Huo, T.; Liu, X.; et al. Global, Regional and National Burden of Anxiety and Depression Disorders from 1990 to 2021, and Forecasts up to 2040. J. Affect. Disord. 2026, 393, 120299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dou, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, X.; Ma, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, W. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Mental Disorders among Adolescents and Young Adults, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Transl Psychiatry 2025, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongjun, Z.; Mingyue, W.; Xinqi, L.; Lina, W.; Jiali, W.; Mengyao, J. Trends in Depressive and Anxiety Disorders among Adolescents and Young Adults (Aged 10–24) from 1990 to 2021: A Global Burden of Disease Study Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 387, 119491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisie, V.; Puiu, M.G.; Manea, M.; Pacearcă, I.A. Predictors of Changes in Quality of Life of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder—A Prospective Naturalistic 3-Month Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, U.; Cortese, S.; Flor, M.; Moncada-Parra, A.; Lecumberri, A.; Eudave, L.; Magallón, S.; García-González, S.; Sobrino-Morras, Á.; Piqué, I.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Disorder Symptoms among University Students: An Umbrella Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 175, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, L.; Alayo, I.; Vilagut, G.; Mortier, P.; Almenara, J.; Cebrià, A.I.; Echeburúa, E.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; Lagares, C.; et al. Predictive Models for First-Onset and Persistence of Depression and Anxiety among University Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnink, M.; Ballester, L.; Vilagut, G.; Alayo, I.; Mortier, P.; Almenara, J.; Cebrià, A.I.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; Lagares, C.; et al. Depression and Anxiety: A 3-Year Follow-up Study of Associated Risk and Protective Factors among University Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 391, 120058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Cai, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Z. Multidimensional Stressors and Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents: A Network Analysis through Simulations. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Limas, K.; Miranda-Barrera, V.A.; Muñoz-Díaz, K.F.; Novales-Huidobro, S.R.; Chico-Barba, G. Body Dissatisfaction, Distorted Body Image and Disordered Eating Behaviors in University Students: An Analysis from 2017–2022. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, B.S.; Huchchannavar, R.; Doddamani, A.; Manjula, A.; Alok, Y.; Kini, B.S.; Anusha Bhat, N.; Krishnan, A. Mirror, Mirror on the Coast: Exploring Body Image Perception and Its Nexus with Self-Esteem, Mental Well-Being among Student Population at an Education Hub in South-India. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon-Krakus, S.; Sabiston, C.M.; Brunet, J.; Castonguay, A.L.; Maximova, K.; Henderson, M. Body Image Self-Discrepancy and Depressive Symptoms Among Early Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; Abhyankar, P.; Dimova, E.; Best, C. Associations between Body Dissatisfaction and Self-Reported Anxiety and Depression in Otherwise Healthy Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.E.; Latner, J.D.; Hayashi, K. More than Just Body Weight: The Role of Body Image in Psychological and Physical Functioning. Body Image 2013, 10, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darimont, T.; Karavasiloglou, N.; Hysaj, O.; Richard, A.; Rohrmann, S. Body Weight and Self-Perception Are Associated with Depression: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2016. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Kersbergen, I.; Sutin, A.; Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Does Perceived Overweight Increase Risk of Depressive Symptoms and Suicidality beyond Objective Weight Status? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 73, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Truong Thi Khanh, H.; Lizińczyk, S.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lipowska, M.; Gulbicka, A. Body Dissatisfaction, Restrictive, and Bulimic Behaviours among Young Women: A Polish–Japanese Comparison. Nutrients 2020, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Túry, F.; Szabó, P.; Dukay-Szabó, S.; Szumska, I.; Simon, D.; Rathner, G. Eating Disorder Characteristics among Hungarian Medical Students: Changes between 1989 and 2011. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 9, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K. Sociocultural Appearance Standards and Risk Factors for Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Women of Various Ages. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.; Szpakowska, I.; Swami, V. Weight Discrepancy and Body Appreciation among Women in Poland and Britain. Body Image 2013, 10, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babosová, R.; Matejovičová, B.; Langraf, V.; Kopecký, M.; Sandanusová, A.; Petrovičová, K.; Schlarmannová, J. Differences in the Body Image Based on Physical Parameters among Young Women from the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godina, E.Z.; Sineva, I.M.; Khafizova, A.A.; Okushko, R.V.; Negasheva, M.A. Gender and Regional Differences in Body Image Dissatisfaction in Modern University Students: A Pilot Study in Two Cities of Eastern Europe. Coll. Antropol. 2020, 44, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Slobodskaya, H.R.; Kaneko, H. Adolescent Mental Health in Japan and Russia: The Role of Body Image, Bullying Victimisation and School Environment. Int. J. Psychol. 2024, 59, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motorga, R.; Ionescu, M.; Nechita, F.; Micu, D.; Băluțoiu, I.; Dinu, M.M.; Nechita, D. Eating Disorders in Medical Students: Prevalence, Risk Factors, Comparison with the General Population. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1515084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.L.S.; Chow, P.P.K.; Wong, F.M.F.; Ho, M.M. Associations among Stressors, Perceived Stress, and Psychological Distress in Nursing Students: A Mixed Methods Longitudinal Study of a Hong Kong Sample. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1234354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Liu, C.; Du, Q.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, S.; Dad, O.; Tian, Y.; Li, K. Source of Stress-Associated Factors Among Medical and Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2025, 2025, 9928649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R.; Nadolu, D.; David, G. Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duica, C.L.; Negoita, S.I.; Pleșea-Condratovici, A.; Moroianu, L.-A.; Ignat, M.D.; Nicolcescu, P.; Ciubara, A.; Robles-Rivera, K.; Mititelu-Tartau, L.; Pleșea-Condratovici, C. Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A Novel Web-Based Method for Running Online Questionnaires and Reaction-Time Experiments. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A Software Package for Programming Psychological Experiments Using Linux. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire 2011; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020.

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, M.; Machado, D.B.; Jin, H.; Scherer, N.; Sun, W.; Sha, F.; Smythe, T.; Ford, T.J.; et al. Dose-Dependent Association Between Body Mass Index and Mental Health and Changes Over Time. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, E.; De Stavola, B.L.; Kellock, M.D.; Kelly, Y.; Lewis, G.; McMunn, A.; Nicholls, D.; Patalay, P.; Solmi, F. Longitudinal Pathways between Childhood BMI, Body Dissatisfaction, and Adolescent Depression: An Observational Study Using the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drosopoulou, G.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Mastorakos, G.; Vlachopapadopoulou, E.; Michalacos, S.; Tzavara, C.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsitsika, A. Psychosocial Health of Adolescents in Relation to Underweight, Overweight/Obese Status: The EU NET ADB Survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C. Self-Esteem and Body Image Perception in a Sample of University Students. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2016, 16, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ping, S.; Liu, X. Gender Differences in Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among College Students: A Longitudinal Study from China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Cai, H.; Bai, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Liu, R.; et al. Gender Differences in Body Appreciation and Its Associations with Psychiatric Symptoms Among Chinese College Students: A Nationwide Survey. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 771398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Du, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, G. Relationships between Physical Activity, Body Image, BMI, Depression and Anxiety in Chinese College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielewska, M.K.; Godzwon, J.M.; Gargul, K.; Nawrocka, E.; Konopka, K.; Sobczak, K.; Rudnik, A.; Zdun-Ryzewska, A. Comparing Students of Medical and Social Sciences in Terms of Self-Assessment of Perceived Stress, Quality of Life, and Personal Characteristics. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 815369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; AlKaabi, J.; Trabelsi, K.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Saif, Z.; Seeman, M.V.; Vitiello, M.V. The Worldwide Prevalence of Self-Reported Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms in Medical Students: An Umbrella Review and Meta-Analysis of Meta-Analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 173, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, J.; Jermann, F.; Ghisletta, P.; Rudaz, S.; Bondolfi, G.; Tran, N.T. Psychological Distress and Well-Being among Students of Health Disciplines: The Importance of Academic Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Body Image Concerns and Body Weight Overestimation Do Not Promote Healthy Behaviour: Evidence from Adolescents in Lithuania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hricová, L.; Orosová, O.; Benka, J.; Petkeviciene, J.; Lukács, A. Body Dissatisfaction, Body Mass Index and Self-Determination among University Students from Hungary, Lithuania and Slovakia. Ceska A Slov. Psychiatr. 2015, 111, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bosnic, Z.; Miletic, M.; Volaric, N.; Holik, D.; Volaric, M.; Majnaric, L.T. The Lack of an Association between Body Image Satisfaction and Self-Esteem in High School Students in Eastern Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Study. 2020; preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Möri, M.; Mongillo, F.; Fahr, A. Images of Bodies in Mass and Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction: The Role of Internalization and Self-Discrepancy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1009792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.; Furdui, R.; Gavreliuc, A.; Greenfield, P.M.; Weinstock, M. The Effects of Sociocultural Changes on Epistemic Thinking across Three Generations in Romania. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V.; Frederick, D.A.; Aavik, T.; Alcalay, L.; Allik, J.; Anderson, D.; Andrianto, S.; Arora, A.; Brännström, Å.; Cunningham, J.; et al. The Attractive Female Body Weight and Female Body Dissatisfaction in 26 Countries Across 10 World Regions: Results of the International Body Project I. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid-Cagigal, A.; Kealy, C.; Potts, C.; Mulvenna, M.D.; Byrne, M.; Barry, M.M.; Donohoe, G. Digital Mental Health Interventions for University Students with Mental Health Difficulties: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2025, 19, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 137 | 26.02 (10.21) | 18–53 |

| Gender | 137 | ||

| Female | 106 (77.4%) | ||

| Male | 31 (22.6%) | ||

| Study programme | 137 | ||

| Medicine | 95 (69.0%) | ||

| Nurse | 42 (31.0%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 137 | 24.10 (7.19) | 15.22–41.5 |

| Score HADS-Anxiety | 137 | 6.39 (3.76) | 0–19 |

| Score HADS-Depression | 137 | 4.17 (2.95) | 0–13 |

| EDE-Q Form Concern | 137 | 1.84 (1.67) | 0–6 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern | 137 | 1.63 (1.69) | 0–6 |

| EDE-Q Alimentation Concern | 137 | 0.81 (1.18) | 0–5.6 |

| BMI Categories | 137 | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 13 (9.5%) | ||

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9) | 76 (55.5%) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 32 (23.4%) | ||

| Obese (≥30.0) | 16 (11.7%) | ||

| Anxiety Categories (HADS-A) | 137 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 80 (58.4%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 32 (23.4%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 25 (18.2%) | ||

| Depression categories (HADS-D) | 137 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 118 (86.1%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 13 (9.5%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 6 (4.4%) | 18–53 |

| Variable | BMI | EDE-Q Restraint | EDE-Q Alimentation Concern | EDE-Q Form Concern | EDE-Q Weight Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score HADS-A | |||||

| ρ | −0.127 | 0.121 | 0.334 | 0.320 | 0.318 |

| p | 0.138 | 0.160 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Score HADS-D | |||||

| ρ | 0.065 | 0.099 | 0.267 | 0.199 | 0.247 |

| p | 0.448 | 0.248 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.004 |

| Variable | N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 95 | 21.58 (5.13) | 18–38 |

| Gender | 95 | ||

| Female | 67 (70.5%) | ||

| Male | 28 (29.5%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 95 | 23.02 (4.27) | 15.22–41.5 |

| Score HADS-Anxiety | 95 | 6.97 (3.64) | 0–19 |

| Score HADS-Depression | 95 | 4.08 (2.80) | 0–13 |

| EDE-Q Form Concern | 95 | 1.87 (1.52) | 0–6 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern | 95 | 1.61 (1.48) | 0–6 |

| EDE-Q Alimentation Concern | 95 | 0.83 (1.17) | 0–5.6 |

| BMI Categories | 95 | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 10 (10.5%) | ||

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9) | 59 (62.1%) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 20 (21.1%) | ||

| Obese (≥30.0) | 6 (6.3%) | ||

| Anxiety Categories (HADS-A) | 95 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 55 (57.9%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 26 (27.4%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 14 (14.7%) | ||

| Depression categories (HADS-D) | 95 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 82 (86.3%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 10 (10.5%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 3 (3.2%) |

| Variable | N | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 | 36.32 (11.64) | 19–53 |

| Gender | 42 | ||

| Female | 39 (92.86%) | ||

| Male | 3 (7.14%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 42 | 25.73 (4.54) | 18.00–36.57 |

| Score HADS-Anxiety | 42 | 6.60 (4.01) | 0–13 |

| Score HADS-Depression | 42 | 4.08 (3.09) | 0–12 |

| EDE-Q Form Concern | 42 | 2.17 (1.46) | 0–5.75 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern | 42 | 1.71 (1.45) | 0–5.8 |

| EDE-Q Alimentation Concern | 42 | 0.92 (1.18) | 0–4.2 |

| BMI Categories | 42 | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 3 (7.1%) | ||

| Normal Weight (18.5–24.9) | 17 (40.5%) | ||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 12 (28.6%) | ||

| Obese (≥30.0) | 10 (23.8%) | ||

| Anxiety Categories (HADS-A) | 42 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 25 (59.5%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 6 (14.3%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 11 (26.2%) | ||

| Depression categories (HADS-D) | 42 | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 36 (85.7%) | ||

| Borderline (8–10) | 3 (7.1%) | ||

| Abnormal (≥11) | 3 (7.1%) |

| Variable | Medicine Mean (IQR) | Nurse Mean (IQR) | U-Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.36 (4.72) | 24.98 (6.73) | 1354.0 | 0.004 |

| Score HADS-A | 7 (5) | 7 (7) | 1942.0 | 0.902 |

| Score HADS-D | 4 (4) | 4 (5) | 1960.5 | 0.972 |

| EDE-Q Form Concern | 1.50 (2.12) | 2.13 (2.50) | 1665.5 | 0.155 |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern | 1.20 (2.20) | 1.60 (2.00) | 1819.0 | 0.483 |

| EDE-Q Alimentation Concern | 0.40 (1.40) | 0.40 (1.60) | 1883.0 | 0.685 |

| Country/Region | Sample | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | Medical students | High risk of eating disorders (37.1%), higher than in the general population. Family pressure is a stronger predictor than media pressure. | [23] |

| Poland | University students | High body dissatisfaction; women are more willing to diet. Only 1 in 5 students is fully satisfied with their appearance. Greater tolerance for overweight than for underweight. | [18,19] |

| Czech Republic | Adolescents | Females with normal BMI want to lose weight. Women are more critical of their bodies. Criticism from others (parents, peers) amplifies dissatisfaction. | [20] |

| Slovakia | Adolescents | Over 35% of girls perceive themselves as “too fat.” Weight-control behaviours are common but do not necessarily align with actual obesity. | [20] |

| Lithuania | Adolescents | Higher BMI and weight overestimation are associated with greater body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Body dissatisfaction does not promote healthy behaviours. | [43] |

| Hungary | University students | Linear relationship between body dissatisfaction and BMI in both men and women. Low self-determination is associated with greater dissatisfaction. | [44] |

| Moscow/Tiraspol | University students | Similar levels of dissatisfaction in both sexes (69% men, 67% women), but for different reasons: men due to underweight, women due to overweight. | [21] |

| Croatia | High school students | Lack of an association between low self-esteem and self-evaluation of appearance, possibly due to traditional values. | [45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pleșea-Condratovici, C.; Dionisie, V.; Moroianu, L.-A.; Serban, P.-S.; Plesea-Condratovici, V.; Arbune, M. Perception Versus Actual Weight: Body Image Dissatisfaction as a Stronger Correlate of Anxiety and Depression than BMI Among Romanian Health Sciences Students. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233118

Pleșea-Condratovici C, Dionisie V, Moroianu L-A, Serban P-S, Plesea-Condratovici V, Arbune M. Perception Versus Actual Weight: Body Image Dissatisfaction as a Stronger Correlate of Anxiety and Depression than BMI Among Romanian Health Sciences Students. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233118

Chicago/Turabian StylePleșea-Condratovici, Catalin, Vlad Dionisie, Lavina-Alexandra Moroianu, Petrut-Stefan Serban, Victor Plesea-Condratovici, and Manuela Arbune. 2025. "Perception Versus Actual Weight: Body Image Dissatisfaction as a Stronger Correlate of Anxiety and Depression than BMI Among Romanian Health Sciences Students" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233118

APA StylePleșea-Condratovici, C., Dionisie, V., Moroianu, L.-A., Serban, P.-S., Plesea-Condratovici, V., & Arbune, M. (2025). Perception Versus Actual Weight: Body Image Dissatisfaction as a Stronger Correlate of Anxiety and Depression than BMI Among Romanian Health Sciences Students. Healthcare, 13(23), 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233118