Psychometric Validation of the Arabic FRAIL Scale for Frailty Assessment Among Older Adults with Colorectal Cancer

Highlights

- The FRAIL-AR scale demonstrated good internal consistency and good test–retest reliability.

- FRAIL-AR scores in elderly Colorectal Cancer patients significantly correlated with function, as well as their quality of life.

- The FRAIL-AR is a reliable and culturally appropriate tool enabling geriatricians and oncologists to perform rapid frailty screening in Arabic-speaking older adults with Colorectal Cancer.

- Implementation of the validated FRAIL-AR scale can support personalized treatment planning and the development of targeted interventions to ultimately improve outcomes for CRC patients.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

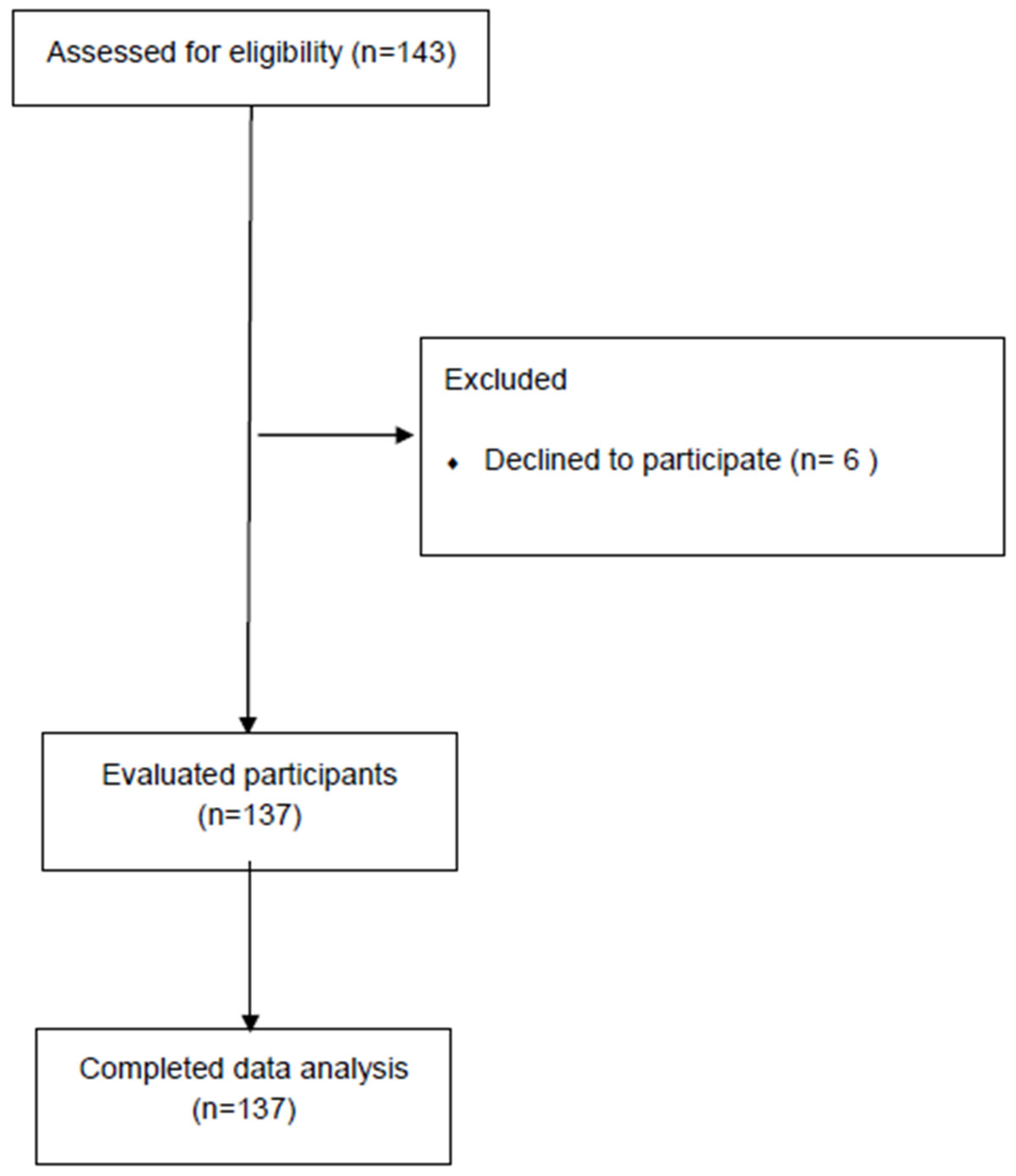

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Outcome Measures and Procedure

2.3.1. Five-Point Indicators Frailty Scale

2.3.2. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (Version 3.0)

2.3.3. Timed up and Go (TUG)

2.3.4. Five Times Sit to Stand Test (5xSTS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Reliability Analysis

2.4.2. Floor and Ceiling Effects

2.4.3. Validity Analysis

- FRAIL-AR scores will be significantly greater among CRC patients ≥ 75 years compared to those aged 65–74 years.

- Among older CRC patients, women will have higher FRAIL scores than men.

- Among older adult CRC patients, those with a severe CCI score (≥5) will demonstrate greater FRAIL-AR scores in comparison to those with a moderate CCI (3–4).

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Reliability

3.3. Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| FRAIL-AR scale | Arabic FRAIL scale |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go Test |

| 5xSTS | Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test (used in Methods and Results) |

| KR-20 | Kuder-Richardson formula 20 |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| KFSHRC-Jeddah | King Faisal Specialist Hospital Research Center in Jeddah |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 |

| QOL | Quality of Life |

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimate from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. What You Need to Know About Cancer of the Colon and Rectum; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud Maturana, M.; English, W.J.; Nandakumar, M.; Li Chen, J.; Dvorkin, L. The impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic literature review. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Gao, Z.; Liao, J.; Jiang, Y.; He, Y. Frailty affects prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1017183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.W.; Tang, W.R.; Chen, S.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Chen, J.S.; Hung, Y.S.; Chou, W.C. Association of frailty and chemotherapy-related adverse outcomes in geriatric patients with cancer: A pilot observational study in Taiwan. Aging 2021, 13, 24192–24204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lan, J.; Yu, F.; Liu, J. Frailty worsens long-term survival in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1326292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.A.; Logan, B.; Reid, N.; Gordon, E.H.; Ladwa, R.; Hubbard, R.E. How frail is frail in oncology studies? A scoping review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, R.; Okoye, C.; Antognoli, R.; Pompilii, I.M.; Taverni, I.; Landi, T.; Ghilli, M.; Roncella, M.; Calsolaro, V.; Monzani, F.; et al. Multidimensional Oncological Frailty Scale (MOFS): A New Quick-To-Use Tool for Detecting Frailty and Stratifying Risk in Older Patients with Cancer-Development and Validation Pilot Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pélissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunello, A.; Fontana, A.; Zafferri, V.; Panza, F.; Fiduccia, P.; Basso, U.; Copetti, M.; Lonardi, S.; Roma, A.; Falci, C.; et al. Development of an oncological-multidimensional prognostic index (Onco-MPI) for mortality prediction in older cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 142, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellan van Kan, G.; Rolland, Y.M.; Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B. Frailty: Toward a clinical definition. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellan van Kan, G.; Rolland, Y.; Bergman, H.; Morley, J.E.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Vellas, B. The I.A.N.A Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Rivera, A.F.; Alves de Oliveira Lucchesi, P.; Andrade Anziani, M.; Lillo, P.; Ferretti-Rebustini, R.E.L. Psychometric Properties of the FRAIL Scale for Frailty Screening: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Yu, R.; Wong, M.; Yeung, F.; Wong, M.; Lum, C. Frailty Screening in the Community Using the FRAIL Scale. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Jing, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Cao, L.; Yang, X.; Xu, L.; et al. A Pilot Study of the FRAIL Scale on Predicting Outcomes in Chinese Elderly People with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 714.e7–714.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.A.; Mishra, G.D.; Dobson, A.J. Validity and responsiveness of the FRAIL scale in a longitudinal cohort study of older Australian women. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2025, 16, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Grüneberg, C.; Thiel, C. German translation, cross-cultural adaptation and diagnostic test accuracy of three frailty screening tools: PRISMA-7, FRAIL scale and Groningen Frailty Indicator. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 51, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Qiao, X.; Tian, X.; Liu, N.; Jin, Y.; Si, H.; Wang, C. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the FRAIL Scale in Chinese Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.I. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: Clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Carrasco, O.; Cruz-Arenas, E.; Parra-Rodríguez, L.; García-González, A.I.; Contreras-González, L.H.; Szlejf, C. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the FRAIL Scale to Assess Frailty in Mexican Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, B.A.; Nasser, T.A. Assessment of frailty in Saudi community-dwelling older adults: Validation of measurements. Ann. Saudi Med. 2019, 39, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocarnik, J.M.; Hua, X.; Hardikar, S.; Robinson, J.; Lindor, N.M.; Win, A.K.; Hopper, J.L.; Figueiredo, J.C.; Potter, J.D.; Campbell, P.T.; et al. Long-term weight loss after colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with lower survival: The Colon Cancer Family Registry. Cancer 2017, 123, 4701–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Caan, B.J.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Weltzien, E.; Xiao, J.; Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Kroenke, C.H.; Castillo, A.; Kwan, M.L.; Prado, C.M. The deterioration of muscle mass and radiodensity is prognostic of poor survival in stage I-III colorectal cancer: A population-based cohort study (C-SCANS). J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aapro, M.; Scotte, F.; Bouillet, T.; Currow, D.; Vigano, A. A Practical Approach to Fatigue Management in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, D.E.; Pătraşcu, T.; Georgescu, T.F.; Tulin, A.; Mosoia, L.; Bacalbasa, N.; Stiru, O.; Georgescu, M.T. Diabetes Mellitus as a Prognostic Factor for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Vivo 2021, 35, 2495–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Baleiras, M.; Dias Domingues, T.; Severino, E.; Vasques, C.; Neves, M.T.; Ferreira, A.; Vasconcelos de Matos, L.; Ferreira, F.; Miranda, H.; Martins, A. Prognostic Impact of Type 2 Diabetes in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cureus 2023, 15, e33916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jameel, H.; Hameed, W.; Alshagroud, M. An evaluation of the demographic transition and health status of the elderly population in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4704–4711. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, B.A.; Alenazi, A.M.; Alshehri, M.M.; Osailan, A.M.; Alsubaie, S.F.; Alqahtani, M.A. Prevalence of frailty and associated factors among Saudi community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, B.A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Alenazi, A.M. Psychometric analysis of the Arabic (Saudi) Tilburg Frailty Indicator among Saudi community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 90, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodhayani, A.A.; Alsaad, S.M.; Almofarej, N.; Alrasheed, N.; Alotaibi, B. Frailty, sarcopenia and health related outcomes among elderly patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, S.M.; Alghamdi, K.A.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Alsahli, N.A.; Alshamrani, S.A.; Alodhayani, A.A. Frailty and its associated factors among hospitalized older patients in an academic hospital using the FRAIL scale. Int. J. Gerontol. 2022, 16, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Alessa, A.M.; Khan, A.S. Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e64564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hoore, W.; Bouckaert, A.; Tilquin, C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, G.; AlAnsari, A. Reliability and Validity of the Arabic Version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 Questionnaires. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 3045–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijer, H.A.; Sagherian, K.; Tamim, H. Validation of the Arabic version of the EORTC quality of life questionnaire among cancer patients in Lebanon. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Alsulaiman, R.; Doodson, L.; El Ayoubi, H.R. An assessment of reliability and validity of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 among breast cancer patients in Qatar. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2017, 6, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwood, J.; Rybicki, K. Assessment of Gait Speed and Timed Up and Go Measures as Predictors of Falls in Older Breast Cancer Survivors. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 15347354211006462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, S.; Huisman, M.G.; Ghignone, F.; Vigano, A.; de Liguori Carino, N.; Farinella, E.; Girocchi, R.; Audisio, R.A.; van Munster, B.; de Bock, G.H.; et al. Timed up and go test and long-term survival in older adults after oncologic surgery. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Kumar, S.; Dhekale, R.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Mahajan, S.; Daptardar, A.; Ramaswamy, A.; Noronha, V.; Gota, V.; Banavali, S.; et al. Timed Up and Go as a predictor of mortality in older Indian patients with cancer: An observational study. Cancer Res. Stat. Treat. 2022, 5, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzioğlu, Ö.; Dinçer, S.; Özdemir, A.E.; Öztürk, Ö. Physical performance tests have excellent reliability in frail and non-frail patients with prostate cancer. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Measurement of sit-to-stand among older adults. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2012, 28, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmet, H.; Yang, A.W.H.; Robinson, S.R. What is the optimal chair stand test protocol for older adults? A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, S.L.; Wrisley, D.M.; Marchetti, G.F.; Gee, M.A.; Redfern, M.S.; Furman, J.M. Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: Validity of data for the Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, J.; Rybicki, K. Physical function measurement in older long-term cancer survivors. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2021, 6, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R. A note on the estimation of test reliability by the Kuder-Richardson formula (20). Psychometrika 1949, 14, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N. On correlation coefficients and their interpretation. J. Orthod. 2022, 49, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Wang, R.; Wei, J.; Zan, Q.; Shang, L.; Ma, J.; Yao, S.; Xu, C. Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the Japan Frailty Scale. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1257223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; Frutos-Vivar, F.; Moro-Tejedor, M.N.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.M.; Romero-de, S.P.E.; Santana-Padilla, Y.G.; Via-Clavero, G.; Villar-Redondo, M.D.R.; Frade-Mera, M.J.; Juncos-Gozalo, M.; et al. Validity of the FRAIL-España scale for critically ill patients. Med. Intensiva Engl. Ed. 2025, 502259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoogdt, N.; De Groef, A.; Hendrickx, A.; Damstra, R.; Christiaansen, A.; Geraerts, I.; Vervloesem, N.; Vergote, I.; Van Kampen, M. Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL): Reliability and validity. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Leung, J.; Morley, J.E. Comparison of frailty indicators based on clinical phenotype and the multiple deficit approach in predicting mortality and physical limitation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, Z.; Flicker, L.; Almeida, O.P.; Hankey, G.J.; McCaul, K.A.; Chubb, S.A.; Yeap, B.B. Low free testosterone predicts frailty in older men: The health in men study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3165–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, D.; Flicker, L.; Dobson, A. Validation of the frail scale in a cohort of older Australian women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Mou, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, M.; Wang, K. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the FRAIL-NH scale for Chinese nursing home residents: A methodological and cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 105, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, T.; Kishimoto, H.; Susaki, Y.; Kumagai, S. Development of a Fried Frailty Phenotype Questionnaire for Use in Screening Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 272–276.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwipa, L.; Apandi, M.; Utomo, P.P.; Hasmirani, M.; Rakhimullah, A.B.; Yulianto, F.A. Adaptation and validation of the Indonesian version of the FRAIL scale and the SARC-F in older adults. Asian J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 16, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, I.; Cezar, N.O.C.; Izbicki, R.; Lin, S.M.; Paulo, D.L.V.; Fattori, A.; Biella, M.M.; Jacob Filho, W.; Yassuda, M.S. Screening for Frailty With the FRAIL Scale: A Comparison With the Phenotype Criteria. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprahamian, I.; Lin, S.M.; Suemoto, C.K.; Apolinario, D.; Oiring de Castro Cezar, N.; Elmadjian, S.M.; Filho, W.J.; Yassuda, M.S. Feasibility and Factor Structure of the FRAIL Scale in Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 367.e11–367.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Nicholl, B.I.; Hanlon, P. Ethnicity and frailty: A systematic review of association with prevalence, incidence, trajectories and risks. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 109, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susanto, M.; Hubbard, R.E.; Gardiner, P.A. Validity and Responsiveness of the FRAIL Scale in Middle-Aged Women. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellas, B.; Balardy, L.; Gillette-Guyonnet, S.; Abellan Van Kan, G.; Ghisolfi-Marque, A.; Subra, J.; Bismuth, S.; Oustric, S.; Cesari, M. Looking for frailty in community-dwelling older persons: The Gérontopôle Frailty Screening Tool (GFST). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexell, J.E.; Downham, D.Y. How to assess the reliability of measurements in rehabilitation. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 84, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkes, M.; Cai, Y.; Trotta, V.; Policicchio, P.; Wen, S.; Dzwil, G.; Davis, N.; Stout, N.L. Predictors of distress among individuals with cancer reporting physical problems. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B.; van Kan, G.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bauer, J.M.; Bernabei, R.; Cesari, M.; Chumlea, W.C.; Doehner, W.; Evans, J.; et al. Frailty consensus: A call to action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, G.M.; Donoghue, O.A.; Horgan, F.; O’Regan, C.; Cronin, H.; Kenny, R.A. Using timed up-and-go to identify frail members of the older population. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Ryoo, J.H.; Campbell, C.; Hollen, P.J.; Williams, I.C. Exploring the challenges of medical/nursing tasks in home care experienced by caregivers of older adults with dementia: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.S.; Feinglass, J.; Thompson, J.; Baker, D.W. In search of ‘low health literacy’: Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.A.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Bartlett, D.B.; Jackson, T.A.; Duggal, N.A.; Lord, J.M. Multisystem physiological perspective of human frailty and its modulation by physical activity. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1137–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, K.; Vetrano, D.L.; Padua, L.; Romano, V.; Rivoiro, C.; Scelfo, B.; Marengoni, A.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Frailty Syndromes in Persons with Cerebrovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Francis, M.D.; Bologna, C.; Moncaglieri, F.; Riva, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Allegrini, P.; Isu, A.; Vigo, B.; Guerriero, F.; et al. Performance of Edmonton Frail Scale on frailty assessment: Its association with multi-dimensional geriatric conditions assessed with specific screening tools. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, K.; Gąsowski, J. Risk Factors for Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases: Are They the Same? In Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases; Veronese, N., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Altshuler, R.D.; Daschner, P.; Salvador Morales, C.; St Germain, D.C.; Guida, J.; Prasanna, P.G.S.; Buchsbaum, J.C. Older adults with cancer and common comorbidities-challenges and opportunities in improving their cancer treatment outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, D.E.; Georgescu, M.T.; Bobircă, F.T.; Georgescu, T.F.; Doran, H.; Pătraşcu, T. Synchronous Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer with Clinical Complete Remission and Important Downstaging after Neoadjuvant Radiochemotherapy—Personalised Therapeutic Approach. Chirurgia 2017, 112, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piringer, G.; Ponholzer, F.; Thaler, J.; Bachleitner-Hofmann, T.; Rumpold, H.; de Vries, A.; Weiss, L.; Greil, R.; Gnant, M.; Öfner, D. Prediction of survival after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer—A retrospective analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1374592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis Statement | Hypothesized Correlation (Spearman) | Calculated Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Hypothesis Confirmed? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convergent Validity Hypothesis (1–18) | ||||

| 1–6 | The overall scores of FRAIL-AR scales and its five domains (fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, and weight loss) would show a weak negative correlation with EORTC QLQ-C30 physical function score (n = 6) | (−0.20 to −0.39) | −0.15 to −0.38 ** | Yes |

| 7–12 | The overall scores of FRAIL-AR scales and its five domains (fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, and weight loss) would show a moderate positive correlation with TUG scores (n = 6). | (0.40–0.59) | 0.40–0.75 ** | Yes |

| 13–18 | The overall scores of FRAIL-AR scales and its five domains (fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, and weight loss) would show a moderate positive correlation with 5xSTS scores (n = 6) | (0.40–0.59) | 0.40–0.63 ** | Yes |

| Discriminate validity hypotheses (19–21) | Hypothesized Test Result (p-value) | Calculated p-value | ||

| 19 | The FRAIL-AR scores would be significantly greater among the participants ≥ 75 years with CRC compared to those aged 65–74 years. | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

| 20 | Older CRC patients would have higher FRAIL scores for women than for main | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

| 21 | Among older adult patients with CRC, those with a severe CCI score (≥5) demonstrated greater FRAIL-AR scores in comparison to those with a moderate CCI (3–4). | p < 0.05 | p < 0.05 * | Yes |

| Variables | Total (n = 137) | 60–74 yrs (n = 101) | Age ≥ 75 yrs (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs Mean (SD) | 68.04 ± 6.99 | 64.78 ± 4.53 | 77.19 ± 3.83 |

| Gender Female Male | 51(37.20%) 86(62.80%) | 39(38.60%) 62(61.40%) | 12(33.30%) 24(66.70%) |

| Marital status Married Single/Divorce/Widowed | 103(75.20%) 34(24.80%) | 82(81.20%) 19(18.80%) | 21(58.30%) 15(41.70%) |

| Education Primary school Intermediate/Secondary school University/higher degree | 56(40.90%) 36(26.30%) 45(32.80%) | 37(36.60%) 28(27.70%) 36(35.70%) | 19(52.80%) 8(22.20%) 9(25.00%) |

| Employment status Employed/self-employed. Unemployed/retired | 38(27.70%) 99(72.30%) | 29(28.70%) 72(71.30%) | 9(25.00%) 27(75.00%) |

| Residential place Urban Rural | 98(71.50%) 39(28.50%) | 29(28.70%) 72(71.30%) | 10(27.80%) 26(72.20%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) <25 ≥25 | 59(43.10%) 78(56.90%) | 47(46.50%) 54(53.50%) | 12(33.30%) 24(66.70%) |

| Smoking Yes No | 29(21.20%) 108(78.80%) | 10(9.90%) 91(90.10%) | 19(52.80%) 17(47.20%) |

| Cancer type Colon Rectal | 90(65.70%) 47(34.30%) | 78(77.20%) 23(22.80%) | 12(33.30%) 24(66.70%) |

| Tumor stage I–II III–IV | 62(45.26%) 75(54.74%) | 51(50.50%) 50(49.50%) | 11(30.60%) 25(69.40%) |

| Cancer duration <3 years ≥3 years | 99(72.30%) 38(27.70%) | 90(89.10%) 11(10.90%) | 9(25.00%) 27(75.00%) |

| Type of intervention Surgery Chemotherapy Radiotherapy Surgical + chemotherapy Chemo + radiotherapy Surgical + chemo + radiotherapy | 20(14.60%) 17(12.40%) 11(8.00%) 28(20.40%) 6(4.40%) 55(40.10%) | 19(18.80%) 14(13.90%) 11(10.90%) 23(22.80%) 4(4.00%) 30(29.70%) | 1(2.80%) 3(8.30%) 0 5(13.90%) 2(5.60%) 25(69.40%) |

| Co-morbidities Mild risk (1–2) Moderate risk 3–4 Sever risk ≥ 5 | 0 80(58.40%) 57(41.60%) | 0 50(49.50%) 51(50.50%) | 0 30(83.30%) 6(16.70%) |

| Domain | Item-To-Total Spearman Correlation (r) (95% CI) | α | ICC2.1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 0.67(0.49–0.71) ** | - | 0.85 (0.71–0.93) ‡ |

| Resistance | 0.71(0.58–0.76) ** | - | 0.89 (0.79–0.95) ‡ |

| Ambulation | 0.71(0.61–0.78) ** | - | 0.71 (0.48–0.85) ‡ |

| Illnesses | 0.48(0.45–0.71) ** | - | 0.94 (0.87–0.97) ‡ |

| Loss of weight | 0.60(0.50–0.79) ** | - | 0.80 (0.62–0.90) ‡ |

| Overall FRAIL score | - | 0.80 (0.73–0.85) | 0.89 (0.77–0.94) ‡ |

| FRAIL-AR Scale | Fatigue | Resistance | Ambulation | Illnesses | Weight Loss | Overall FRAIL Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | rs | rs | rs | rs | rs | |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 Physical function scale | −0.24 * | −0.29 * | −0.32 * | −0.15 * | −0.22 * | −0.38 * |

| TUG score | 0.50 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.75 ** |

| 5xSTS score | 0.40 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.63 ** |

| FRAIL-AR Scale | Age Group (Years) ^ | Gender ^ | CCI Scores ^ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–74 (n = 101) | ≥75 (n = 36) | Male (n = 86) | Female (n = 51) | Moderate 3–4 (n = 80) | Severe ≥ 5 (n = 57) | |

| Robust (score = 0) | 39 (38.60%) | 7(19.44%) | 31(36.05%) | 12(23.50%) | 26(32.50%) | 11(19.30%) |

| Prefrail (score 1–2) | 29(28.70%) | 8(22.22%) | 25(29.07%) | 15(29.40%) | 25(31.30%) | 15(26.30%) |

| Frail (score ≥ 3) | 33(32.70%) | 21(58.34%) ** | 30(34.88%) | 24(47.10%) * | 29 (36.20%) | 31(54.40%) * |

| Effect size (95%CI) (Overall FRAIL score) | 0.38 * (0.1–0.67) | 0.45 * (0.15–0.84) | 0.49 * (0.1–0.79) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omar, M.T.A.; Alamri, B.N.M.; Mesfer, A.M.; Al-Malki, M.H.; Allehebi, A.; Ibrahim, Z.M.; Gwada, R.F.M. Psychometric Validation of the Arabic FRAIL Scale for Frailty Assessment Among Older Adults with Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233117

Omar MTA, Alamri BNM, Mesfer AM, Al-Malki MH, Allehebi A, Ibrahim ZM, Gwada RFM. Psychometric Validation of the Arabic FRAIL Scale for Frailty Assessment Among Older Adults with Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233117

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmar, Mohammed T. A., Bader Nasser M. Alamri, Ahmed Mohammed Mesfer, Majed Hassan Al-Malki, Ahmed Allehebi, Zizi M. Ibrahim, and Rehab F. M. Gwada. 2025. "Psychometric Validation of the Arabic FRAIL Scale for Frailty Assessment Among Older Adults with Colorectal Cancer" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233117

APA StyleOmar, M. T. A., Alamri, B. N. M., Mesfer, A. M., Al-Malki, M. H., Allehebi, A., Ibrahim, Z. M., & Gwada, R. F. M. (2025). Psychometric Validation of the Arabic FRAIL Scale for Frailty Assessment Among Older Adults with Colorectal Cancer. Healthcare, 13(23), 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233117