Relationship Satisfaction and Body Image-Related Quality of Life as Correlates of Sexual Function During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

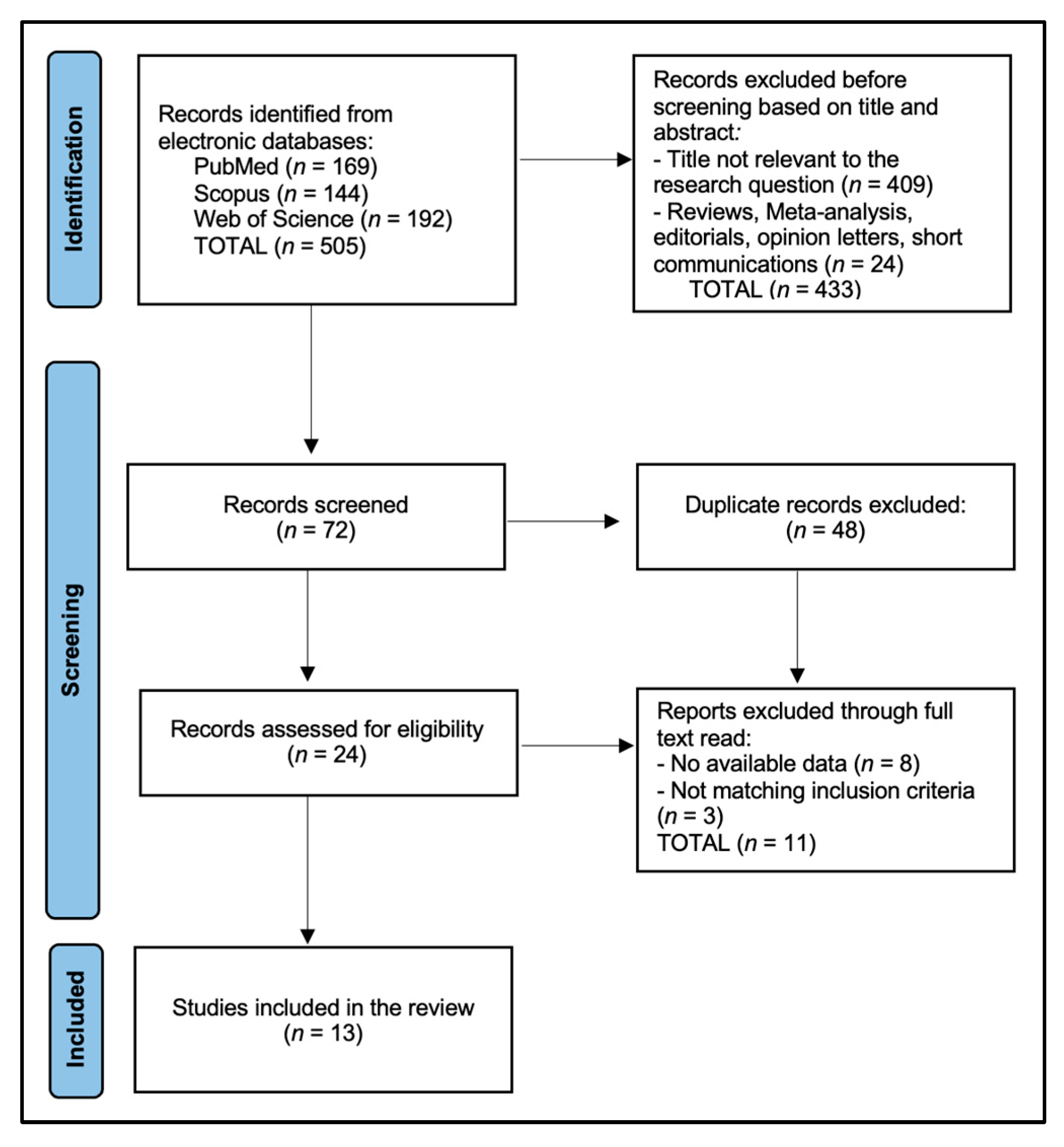

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting Framework

2.2. Review Question and PICO

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Information Sources

2.5. Data Items and Extraction

2.6. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Douglas, J.M., Jr.; Fenton, K.A. Understanding sexual health and its role in more effective prevention programs. Public Health Rep. 2013, 128 (Suppl. S1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narasimhan, M.; Gilmore, K.; Murillo, R.; Allotey, P. Sexual health and well-being across the life course: Call for papers. Bull World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 750–750A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Mitchell, K.R.; Lewis, R.; O’Sullivan, L.F.; Fortenberry, J.D. What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e608–e613, Erratum in Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shuai, H.; Cai, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Krabbendam, E.; Liu, S.; et al. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer, E.B.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Toledo, A.F.Â.; de Siqueira, M.R.; Ferreira, M.E.C.; Neves, C.M. Body Image Assessment Tools in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagl, M.; Jepsen, L.; Linde, K.; Kersting, A. Measuring body image during pregnancy: Psychometric properties and validity of a German translation of the Body Image in Pregnancy Scale (BIPS-G). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fernandes, H.M.; Soler, P.; Monteiro, D.; Cid, L.; Novaes, J. Psychometric Properties of Different Versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire in Female Aesthetic Patients. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hodgkinson, E.L.; Smith, D.M.; Wittkowski, A. Women’s experiences of their pregnancy and postpartum body image: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meston, C.M. Validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with female orgasmic disorder and in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2003, 29, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pereira, A.T.; Barbosa, B.; Lima, R.; Araújo, A.I.; Marques, C.; Pereira, D.; Macedo, A.; Pinto Gouveia, C. Scale for Body Image Concerns During the Perinatal Period—Adaptation and validation. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67 (Suppl. S1), S159–S160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Lawrence, E.; Rothman, A.D.; Cobb, R.J.; Rothman, M.T.; Bradbury, T.N. Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Basson, R. A model of women’s sexual arousal. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2002, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitnick, D.M.; Heyman, R.E.; Smith Slep, A.M. Changes in relationship satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alleva, J.M.; Tylka, T.L.; Kroon Van Diest, A.M. The Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS): Development and psychometric evaluation in U.S. community women and men. Body Image 2017, 23, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daniluc, R.I.; Craina, M.; Thakur, B.R.; Prodan, M.; Bratu, M.L.; Daescu, A.C.; Puenea, G.; Niculescu, B.; Negrean, R.A. Comparing Relationship Satisfaction and Body-Image-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Planned and Unplanned Pregnancies. Diseases 2024, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daescu, A.-M.C.; Navolan, D.-B.; Dehelean, L.; Frandes, M.; Gaitoane, A.-I.; Daescu, A.; Daniluc, R.-I.; Stoian, D. The Paradox of Sexual Dysfunction Observed during Pregnancy. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Karaahmet, A.; Sule Bilgic, F.; Yilmaz, T.; Dinc Kaya, H. The effect of yoga on sexual function and body image in primiparous pregnant Women: A randomized controlled single-blind study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 278, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senobari, M.; Azmoude, E.; Mousavi, M. The relationship between body mass index, body image, and sexual function: A survey on Iranian pregnant women. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2019, 17, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aksoy Derya, Y.; Gök Uğur, H.; Özşahin, Z. Effects of demographic and obstetric variables with body image on sexual dysfunction in pregnancy: A cross-sectional and comparative study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauls, R.N.; Occhino, J.A.; Dryfhout, V.L. Effects of pregnancy on female sexual function and body image: A prospective study. J. Sex Med. 2008, 5, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoš, S.N.; Vraneš, H.S.; Šunjić, M. Limited role of body satisfaction and body image self-consciousness in sexual frequency and satisfaction in pregnant women. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effati-Daryani, F.; Jahanfar, S.; Mohammadi, A.; Zarei, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. The relationship between sexual function and mental health in Iranian pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalesi, Z.B.; Bokaie, M.; Attari, S.M. Effect of pregnancy on sexual function of couples. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gumusay, M.; Erbil, N.; Demirbag, B.C. Investigation of sexual function and body image of pregnant women and sexual function of their partners. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2021, 36, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, K.; Lehnig, F.; Treml, J.; Nagl, M.; Stepan, H.; Kersting, A. The trajectory of body image dissatisfaction during pregnancy and postpartum and its relationship to Body-Mass-Index. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karamidehkordi, A.; Roudsari, R.L. Body image and its relationship with sexual function and marital adjustment in infertile women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2014, 19 (Suppl. S1), S51–S58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Şolt Kırca, A.; Dagli, E. Sexual attitudes and sexual functions during pregnancy: A comparative study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2023, 19, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ninivaggio, C.; Rogers, R.G.; Leeman, L.; Migliaccio, L.; Teaf, D.; Qualls, C. Sexual function changes during pregnancy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałązka, I.; Drosdzol-Cop, A.; Naworska, B.; Czajkowska, M.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. Changes in the sexual function during pregnancy. J. Sex Med. 2015, 12, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallwiener, S.; Müller, M.; Doster, A.; Kuon, R.J.; Plewniok, K.; Feller, S.; Wallwiener, M.; Reck, C.; Matthies, L.M.; Wallwiener, C. Sexual activity and sexual dysfunction of women in the perinatal period: A longitudinal study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 295, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassis, C.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Morris, E.; Giarenis, I. What happens to female sexual function during pregnancy? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 258, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçükdurmaz, F.; Efe, E.; Malkoç, Ö.; Kolus, E.; Amasyalı, A.S.; Resim, S. Prevalence and correlates of female sexual dysfunction among Turkish pregnant women. Turk. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peivandi, S.; Habibi, A.; Hosseini, S.H.; Khademloo, M.; Motamedi-Rad, E. Sexual function of overweight pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuchs, A.; Czech, I.; Sikora, J.; Fuchs, P.; Lorek, M.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V.; Drosdzol-Cop, A. Sexual Functioning in Pregnant Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, K.; Lehnig, F.; Nagl, M.; Stepan, H.; Kersting, A. Course and prediction of body image dissatisfaction during pregnancy: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahrami_Vazir, E.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Kamalifard, M.; Ghelichkhani, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Mirghafourvand, M. The correlation between sexual dysfunction and intimate partner violence in young women during pregnancy. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2020, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, M.; Aminshokravi, F.; Zayeri, F.; Azin, S.A. Effect of Sexual Education on Sexual Function of Iranian Couples During Pregnancy: A Quasi Experimental Study. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2018, 19, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Study (Year, Country) | Design and N | Timing | Relationship Measure(s) | Body-Image/BI-QoL Measure(s) | Sexual/Other Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniluc et al., 2024 (Romania) [17] | Cross-sectional; N = 144 | All trimesters | PQMR | BESAQ | FSFI |

| Dăescu et al., 2023 (Romania) [18] | Repeated-measures cohort; N = NR | T1–T3 | NR | BESAQ | FSFI, FSD |

| Yıldız Karaahmet et al., 2022 (Turkey) [19] | RCT; N = 140 | Mid-pregnancy | NR | BESAQ | FSFI pre/post |

| Senobari et al., 2019 (Iran) [20] | Cross-sectional; N = 206 | T2–T3 | NR | MBSRQ/BIS | FSFI domains |

| Aksoy Derya et al., 2020 (Turkey) [21] | Cross-sectional; N = 472 | All trimesters | NR | Body Image Scale | FSFI, FSD |

| Pauls et al., 2008 (USA) [22] | Prospective cohort; N = 107 (63 complete) | T1 → T3 → 6 mo pp | Relationship items | BESAQ | FSFI, sexual frequency |

| Radoš et al., 2014 (Croatia) [23] | Cross-sectional; N = 150 | T3 | PQMR | BASS/BISC | Sexual frequency/satisfaction |

| Effati-Daryani et al., 2021 (Iran) [24] | Cross-sectional; N = 437 | All trimesters (COVID-19) | Marital satisfaction (single-item/scale) | NR | FSFI, DASS-21 |

| Khalesi et al., 2018 (Iran) [25] | Cross-sectional couples; N = NR | All trimesters | Marital/partner items | NR | FSFI (women), IIEF (men) |

| Gümüşay et al., 2021 (Turkey) [26] | Cross-sectional couples; N = 254 women + 254 partners | Trimester-stratified | NR | BIS | FSFI; ASEX-Male |

| Linde et al., 2024 (Germany) [27] | Longitudinal cohort; N = 136 | Early → late preg → 8 wk → 1 yr pp | NR | BSQ | BMI trajectory |

| Karamidehkordi & Roudsari, 2014 (Iran) [28] | Cross-sectional; N = 130 infertile women | Non-pregnant | DAS | Modified Body Image Questionnaire | FSFI |

| Şolt Kırca & Dağlı, 2023 (Turkey) [29] | Cross-sectional; N = 200 | All trimesters; Turkish & Syrian | Sexual attitudes | NR | FSFI |

| Study | Relationship Satisfaction (Numeric) | Body-Image/BI-QoL (Numeric) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniluc et al., 2024 (Romania) [17] | PQMR item means (planned + unplanned pooled): Comfort/Warmth 3.90 ± 1.12; Unwilling to confide 2.58 ± 1.09; Relationship strain 2.44 ± 1.11; Arguing 2.55 ± 1.10 | BESAQ: Planned pregnancy β = −0.273 (p = 0.007); 3rd trimester β = −0.280 (p = 0.019); # children β = +0.317 (p = 0.007) (higher = poorer BI-QoL) | Planned pregnancy and later trimester associated with better BI-QoL; more children worse. |

| Dăescu et al., 2023 (Romania) [18] | NR | Higher BESAQ increased FSD risk ~4.24-fold | Repeated-measures: rising BI-exposure anxiety linked to FSD odds. |

| Yıldız Karaahmet et al., 2022 (Turkey) [19] | NR | BESAQ: no significant pre-post change in either arm | RCT yoga—no BI-QoL change despite FSFI gains. |

| Senobari et al., 2019 (Iran) [20] | NR | MBSRQ/BIS subscales reported; correlations to FSFI domains | Body satisfaction domains measured; select domain–FSFI links reported. |

| Aksoy Derya et al., 2020 (Turkey) [21] | NR | Body Image Scale associated with FSD (see OR below) | Each unit change ~OR 0.98 for FSD (direction protective with higher body image). |

| Pauls et al., 2008 (USA) [22] | Relationship items collected; no numeric PQMR | BESAQ worsened postpartum vs. pregnancy (p = 0.01) | BI during sexual activity declined postpartum; see sexual function trajectory. |

| Radoš et al., 2014 (Croatia) [23] | PQMR: body satisfaction and BISC had limited roles after controlling for partnership satisfaction | BASS/BISC used; numerics NR | N = 150; controlled analyses emphasized partnership satisfaction. |

| Effati-Daryani et al., 2021 (Iran) [24] | Higher marital satisfaction predicted higher FSFI (GLM) | NR | Model R2 ≈ 35.8% with marital satisfaction, stress, spouse job, income, residence, gestational age. |

| Khalesi et al., 2018 (Iran) [25] | Couple relationship items; numerics NR | NR | Couples design; sexual function affected across pregnancy. |

| Gümüşay et al., 2021 (Turkey) [26] | NR (focus on couple function) | BIS positively correlated with women’s FSFI; negatively with partners’ sexual function | N = 254 pairs; trimester differences described. |

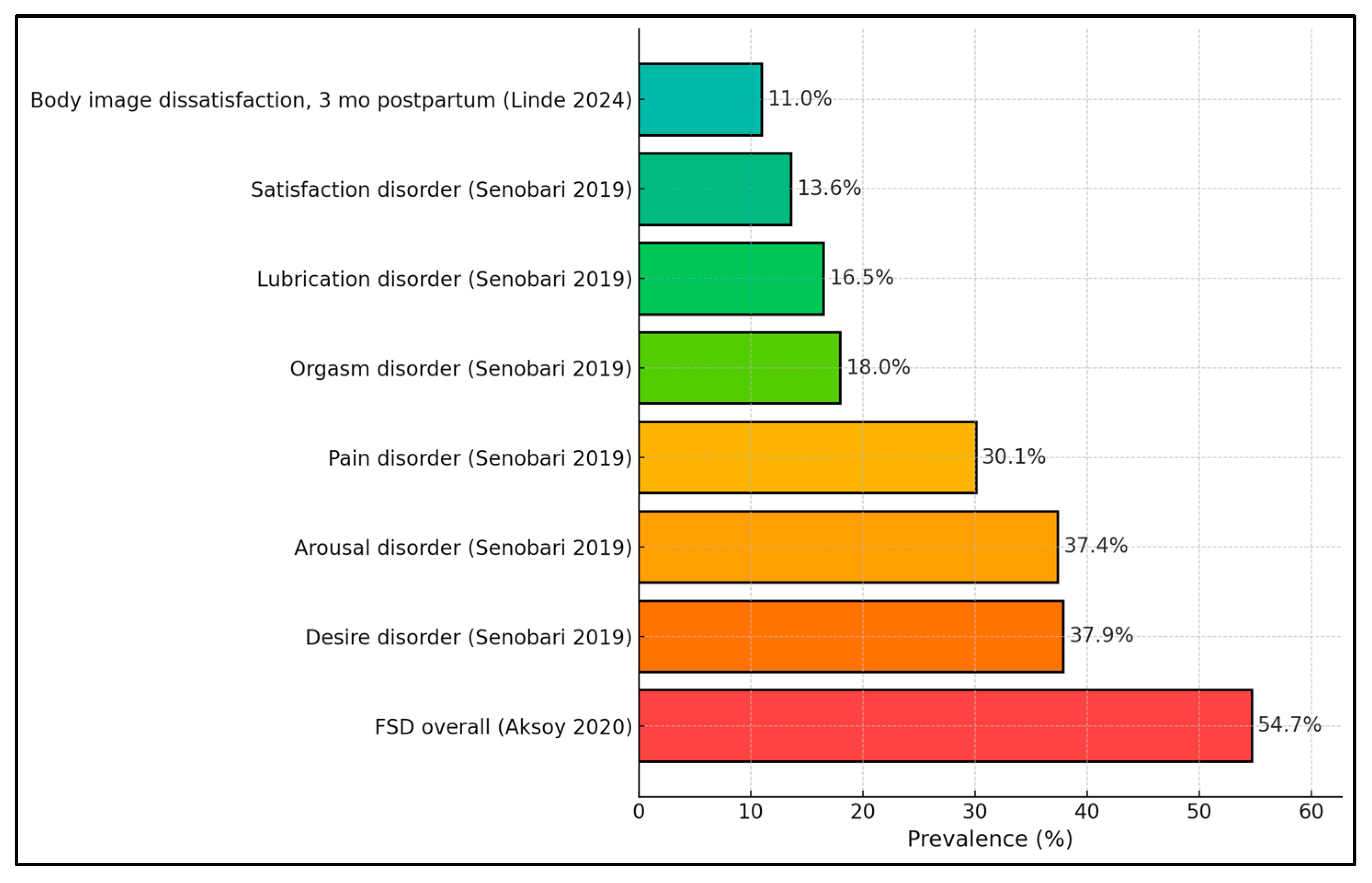

| Linde et al., 2024 (Germany) [27] | NR | BSQ > 100 prevalence: T1 6.6%; T2 2.9%; T3 11.0%; 1 yr pp 10.3% | Weight/shape concern rises by late pregnancy/postpartum. |

| Karamidehkordi & Roudsari, 2014 (Iran) [28] | DAS total 113.8 ± 19.73 | Body image 308.1 ± 45.8 | Infertile women; higher body image associated with higher DAS and FSFI subscales. |

| Şolt Kırca & Dağlı, 2023 (Turkey) [29] | Sexual attitudes measured; relationship satisfaction NR | NR | Comparative (Turkish vs. Syrian) sexual attitudes with FSFI. |

| Study | FSFI Total (Mean ± SD)/Domains | FSD/Sexual Outcomes | Modifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniluc et al., 2024 (Romania) [17] | NR | FSFI used; detailed domain means NR | Predictors of BESAQ: planned pregnancy (β = −0.273), trimester 3 (β = −0.280), # children (β = +0.317). Relationship items reported (see T2). |

| Dăescu et al., 2023 (Romania) [18] | NR | FSD odds ↑ ~4.24× with higher BESAQ | Repeated measures across trimesters; direction robust. |

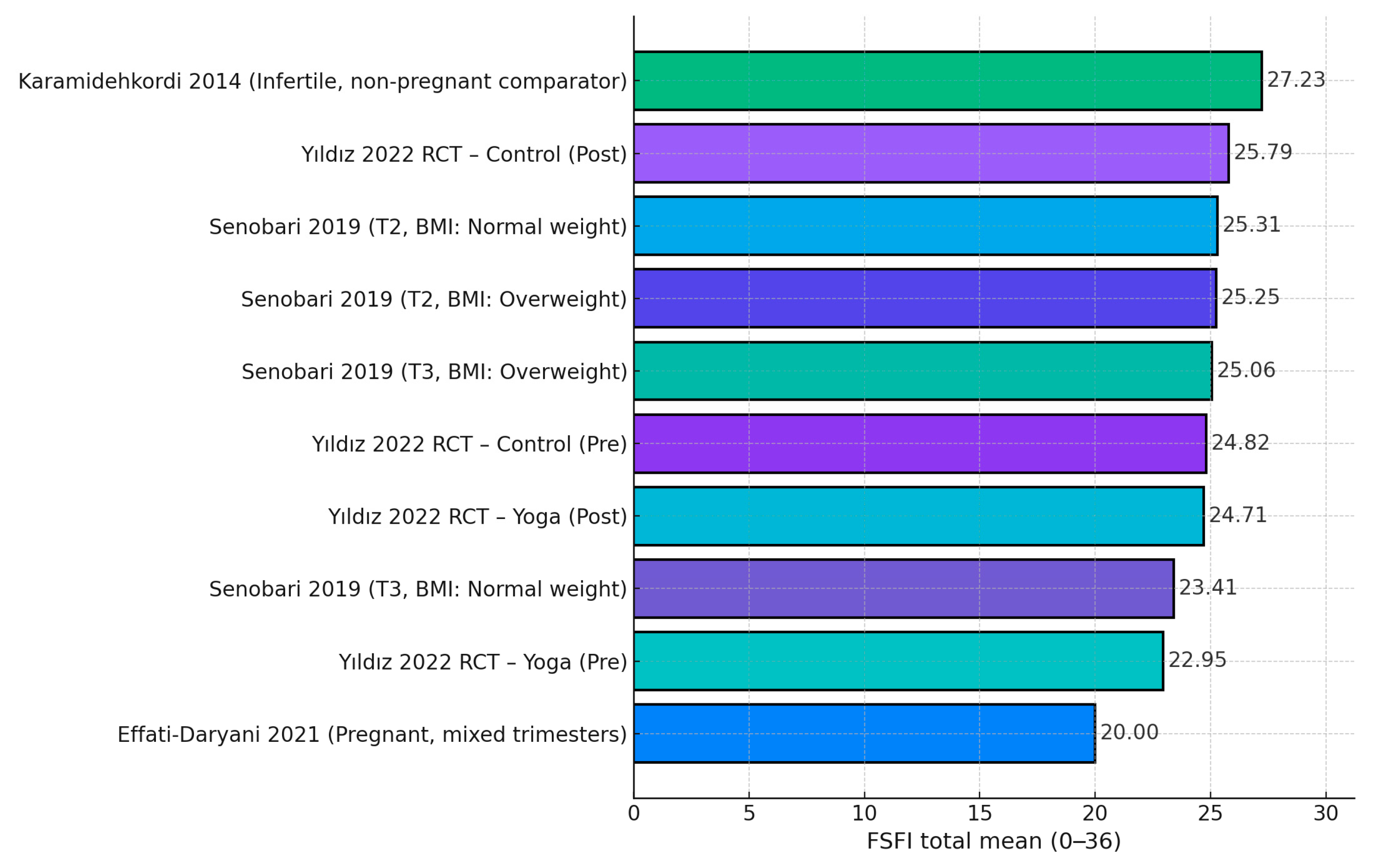

| Yıldız Karaahmet et al., 2022 (Turkey) [19] | Yoga: 22.95 ± 4.14 → 24.71 ± 3.48 (p = 0.002). Control: 24.82 ± 6.15 → 25.79 ± 2.47 (p = 0.181). | Improved sexual function in yoga group; no BESAQ change | FSFI ↔ BESAQ correlations ns (r ≈ −0.10; p > 0.21 both pre/post). |

| Senobari et al., 2019 (Iran) [20] | T2 FSFI: 25.31 ± 4.61 (NW) vs. 25.25 ± 4.45 (OW); T3: 23.41 ± 6.61 (NW) vs. 25.06 ± 5.00 (OW). Domains (T2): desire ~3.4; lubrication ~4.5; satisfaction ~4.8; etc. | Disorder prevalence: Desire 37.9%, Pain 30.1%, Lubrication 16.5%, Satisfaction 13.6%, Orgasm 18.0%, Arousal 37.4% | Trimester and BMI effects small; domain-specific differences non-significant (p > 0.17–0.95 range). |

| Aksoy Derya et al., 2020 (Turkey) [21] | NR | FSD prevalence 54.7% | Body image OR ≈ 0.98/unit; residence, trimester, parity related to FSD. |

| Pauls et al., 2008 (USA) [22] | NR totals | Sexual function declined across pregnancy (p = 0.017); frequency highest pre-pregnancy (p < 0.0005) | BESAQ worsened postpartum (p = 0.01). |

| Radoš et al., 2014 (Croatia) [23] | NR | Sexual satisfaction/frequency predicted more by partnership satisfaction than body image self-consciousness | Third trimester sample (N = 150). |

| Effati-Daryani et al., 2021 (Iran) [24] | FSFI total 20.0 ± 8.50 | Lower FSFI with higher distress | FSFI vs. stress r = −0.203; anxiety r = −0.166; depression r = −0.234 (all p ≤ 0.001); GLM predictors explained 35.8% of variance. |

| Khalesi et al., 2018 (Iran) [25] | NR | Couples’ sexual function affected during pregnancy | Women’s FSFI and partners’ function both change; numerics NR. |

| Gümüşay et al., 2021 (Turkey) [26] | NR | Women’s FSFI highest in 2nd trimester, lowest in 3rd; partners’ dysfunction more frequent in 3rd | Positive correlation: women’s BIS ↔ female FSFI; negative: women’s BIS ↔ partners’ function. |

| Linde et al., 2024 (Germany) [27] | NR | Sexual function not measured | BSQ > 100 rises late pregnancy/postpartum. |

| Karamidehkordi & Roudsari, 2014 (Iran) [28] | FSFI 27.23 ± 3.80 | (Infertile women, contextual) | Higher body image associated with higher FSFI domains and higher DAS. |

| Şolt Kırca & Dağlı, 2023 (Turkey) [29] | NR | FSFI used; comparative attitudes (Turkish vs. Syrian) | Attitudes related to sexual function; numerics NR. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniluc, R.-I.; Craina, M.; Tischer, A.A.; Bondar, A.-C.; Stelea, L.; Bica, M.C.; Stana, L. Relationship Satisfaction and Body Image-Related Quality of Life as Correlates of Sexual Function During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233020

Daniluc R-I, Craina M, Tischer AA, Bondar A-C, Stelea L, Bica MC, Stana L. Relationship Satisfaction and Body Image-Related Quality of Life as Correlates of Sexual Function During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniluc, Razvan-Ionut, Marius Craina, Alina Andreea Tischer, Andrei-Cristian Bondar, Lavinia Stelea, Mihai Calin Bica, and Loredana Stana. 2025. "Relationship Satisfaction and Body Image-Related Quality of Life as Correlates of Sexual Function During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233020

APA StyleDaniluc, R.-I., Craina, M., Tischer, A. A., Bondar, A.-C., Stelea, L., Bica, M. C., & Stana, L. (2025). Relationship Satisfaction and Body Image-Related Quality of Life as Correlates of Sexual Function During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(23), 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233020