The Effectiveness of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review of RCTs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Benefits of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD

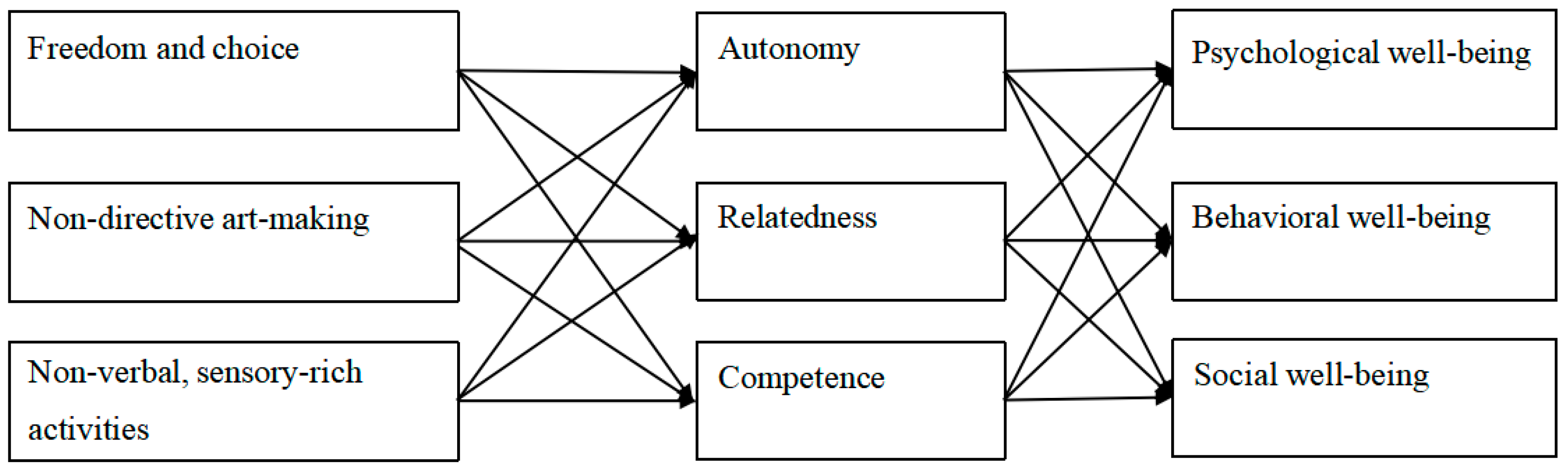

1.2. A Theoretical Framework for Art Therapy in ASD

1.3. Research Gap and Research Questions

- What outcomes have been identified in art therapy for children and adolescents with ASD?

- How effective is art therapy in promoting positive developmental outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD?

- What theoretical frameworks have guided the design of art therapy for children and adolescents with ASD?

- What intervention strategies—regarding art modality and format (e.g., individual vs. group)—are associated with positive outcomes?

- What is the methodological rigor of existing art therapy studies for children and adolescents with ASD?

2. Methods

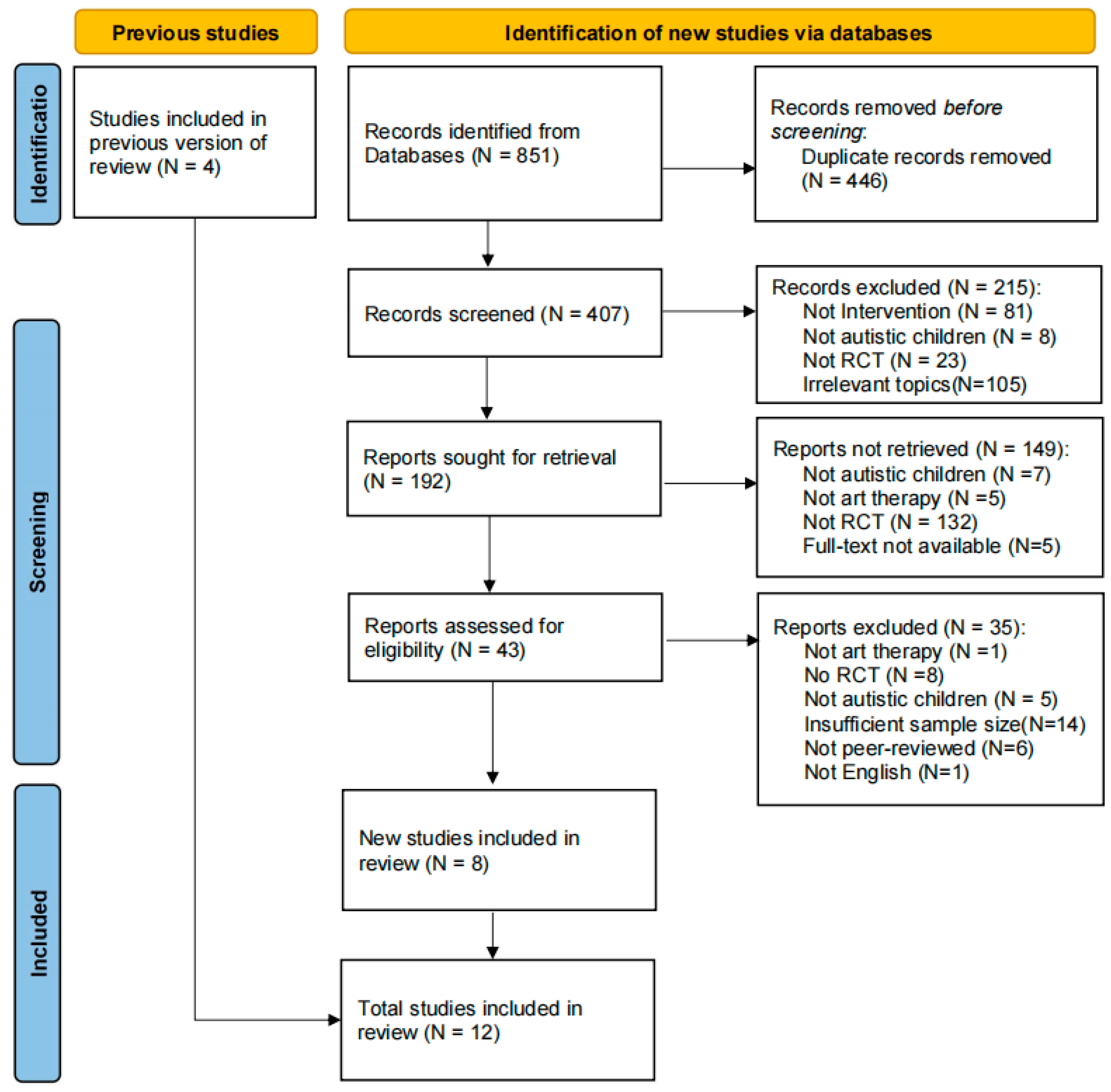

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Rigor

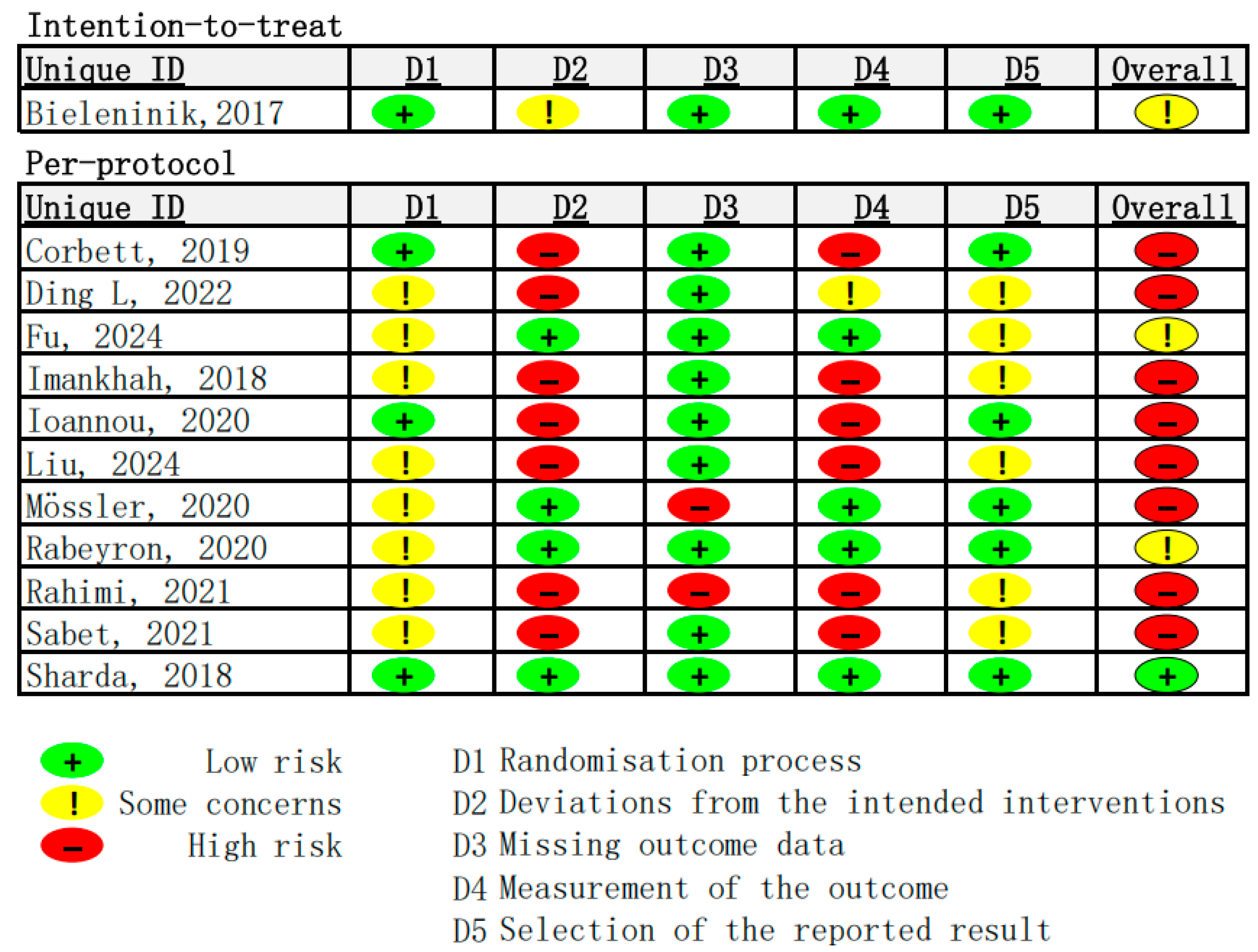

2.4.1. Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (ROB 2.0)

2.4.2. Delphi List with Four Additional Items

3. Results

3.1. Effectiveness of Art Therapy

3.2. Intervention Format

3.3. Theoretical Underpinnings Guiding Intervention

3.4. Methodological Rigor

3.4.1. Risk of Bias

3.4.2. Methodological Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Children and Adolescents with ASD

4.2. Theoretical Frameworks Have Guided the Design of Art Therapy

4.3. Intervention Formats of Art Therapy for Children and Adolescents with ASD

4.4. Methodological Rigor of Existing Art Therapy Studies for Children and Adolescents with ASD

4.5. Implications for Research and Practice

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Terms

Appendix B. Definitions of Different Types of Art Therapy

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Art therapy | Art therapy is a holistic therapeutic approach that integrates principles from mental health, human development, and psychological theory with various art modalities—such as visual art, music, movement, drama, and creative writing—to promote individual and community well-being [18]. |

| Visual art therapy | Visual art therapy is defined as a “therapeutic process based on spontaneous or prompted creative expression using various art materials and art techniques such as painting, drawing, sculpture, clay modeling and collage” [78]. |

| Music therapy | Music Therapy is the clinical & evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program [79]. |

| Dance/movement therapy | The psychotherapeutic use of dance, movement, body awareness, and embodied communication to foster healing and well-being for all individuals, families, and communities [80]. |

| Drama therapy | Drama therapy is one form of art therapy, which utilizes methods and techniques from the performing arts with principles of psychotherapy that promote transformation and evolution. Drama therapists employ a range of artistic techniques through methods such as storytelling, Greek myths, play scripts, puppetry, masks, and improvisation [81]. |

| Poetry/writing therapy | Poetry therapy is the use of language, symbol, and story in therapeutic, educational, growth, and community-building capacities. It relies upon the use of poems, stories, song lyrics, imagery, and metaphor to facilitate personal growth, healing, and greater self-awareness. Bibliotherapy, narrative, journal writing, metaphor, storytelling, and ritual are all within the realm of poetry therapy [82]. |

| Intermodal or Multimodal approaches | Intermodal expressive arts therapy involves the intentional use and integration of multiple artistic modalities within a therapeutic or growth-oriented process. These modalities may include visual arts (such as painting, photography, and crafts), movement and dance, voice, rhythm, sound, and music, as well as drama, enactment, and various forms of writing including poetry and storytelling. Additionally, intermodal practice may incorporate guided meditation, imaginative processes, and nature-based activities to facilitate self-expression, healing, and transformation [83]. |

Appendix C. List of Quality Rating Items

| Items | Yes | No | Don’t Know |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was a method of randomization performed? | □ | □ | □ |

| 2. Was the treatment allocation concealed? | □ | □ | □ |

| 3. Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | □ | □ | □ |

| 4. Were the eligibility criteria specified? | □ | □ | □ |

| 5. Was the outcome assessor blinded? | □ | □ | □ |

| 6. Was the care provider blinded? | □ | □ | □ |

| 7. Was the clients blinded? | □ | □ | □ |

| 8. Were point estimates and measures of variability presented for the primary outcome measures? | □ | □ | □ |

| 9. Did the analysis include an intention-to-treat analysis? | □ | □ | □ |

| 10. Was a sample size justification or power calculation provided? | □ | □ | □ |

| 11. Was the follow-up period sufficiently long (i.e., >3 months) and adequately reported? | □ | □ | □ |

| 12. Was the trial registered? | □ | □ | □ |

| 13. Were the statistical analysis methods clearly described, justified, and appropriate? | □ | □ | □ |

Appendix D. The Results of Quality Rating Scale

| (i) Research Design | (ii) Participants Recruitment | (iii) Intervention Protocol and Follow-Up | (iv) Statistical Appropriateness and Outcome Reporting | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 9 | Item 4 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | Item 8 | Item 13 | |||

| No. | Study | Randomization Reported | Allocation Concealment | Baseline Comparability | Participants Blinding | Providers Blinding | Assessors Blinding | ITT Analysis | Eligibility Criteria | Sample Size Justification | Follow-Up Reported | Trial Registration | Variability Reported | Statistical Appropriateness | |

| 1 | Bieleninik, 2017 [47] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 2 | Corbett, 2019 [48] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 3 | Ding, 2022 [49] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | Fu, 2024 [50] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 5 | Imankhah, 2018 [51] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | Ioannou, 2020 [52] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 7 | Liu, 2024 [53] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 8 | Mössler, 2020 [54] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| 9 | Rabeyron, 2020 [55] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 10 | Rahimi, 2021 [56] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | Sabet, 2021 [57] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 12 | Sharda, 2018 [58] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, T.; King, B.H. Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA 2023, 329, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Shohaimi, S.; Jafarpour, S.; Abdoli, N.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantseva, O.I.; Romanova, R.S.; Shurdova, E.M.; Dolgorukova, T.A.; Sologub, P.S.; Titova, O.S.; Kleeva, D.F.; Grigorenko, E.L. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1071181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, F.D.; Costanzo, A.A.; Finocchiaro, M.; Stimoli, M.A.; Zuccarello, R.; Buono, S.; Ferri, R.; Zoccolotti, P. Academic Skills in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, E.; Chandler, S.; Baird, G.; Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A.; Loucas, T.; Charman, T. The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanouni, P.; Quirke, S.; Blok, J.; Casey, A. Independent living in adults with autism spectrum disorder: Stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, S.; Breitenstein, S.M.; Tucker, S.; Havercamp, S.M.; Ford, J.L. Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Rural Areas: A Literature Review of Mental Health and Social Support. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 61, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentani, H.; de Paula, C.S.; Bordini, D.; Rolim, D.; Sato, F.; Portolese, J.; Pacifico, M.C.; McCracken, J.T. Autism spectrum disorders: An overview on diagnosis and treatment. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2013, 35, S62–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Norton, A.H.; Shkedy, G.; Shkedy, D. How much compliance is too much compliance: Is long-term ABA therapy abuse? Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1641258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, S.; Peters, J.K.; Benner, L.; Hopf, A. A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Social Skills Interventions for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2007, 28, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbank, M.; Bottema-Beutel, K.; Crowley LaPoint, S.; Feldman, J.I.; Barrett, D.J.; Caldwell, N.; Dunham, K.; Crank, J.; Albarran, S.; Woynaroski, T. Autism intervention meta-analysis of early childhood studies (Project AIM): Updated systematic review and secondary analysis. BMJ 2023, 383, e076733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Ratcliff, K.; Hilton, C.; Fingerhut, P.; Li, C.-Y. Art Interventions for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 76, 7605205030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bololia, L.; Williams, J.; Macmahon, K.; Goodall, K. Dramatherapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic integrative review. Arts Psychother. 2022, 80, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Escribano, C.; Orío-Aparicio, C. Creative arts therapy for autistic children: A systematic review. Arts Psychother. 2024, 91, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S.W.; Mullins, K.L.; Kumar, S. Art therapy for children and adolescents with autism: A systematic review. Int. J. Art. Ther. 2025, 30, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N. The Creative Connection: Expressive Arts as Healing; Science & Behavior Books: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Expressive arts therapy and multimodal approaches. In Handbook of Art Therapy, 6th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 106–119. [Google Scholar]

- Versitano, S.; Tesson, S.; Lee, C.-W.; Linnell, S.; Perkes, I. Art therapy with children and adolescents experiencing acute or severe mental health conditions: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2025, 59, 863–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, C.; Knorth, E.J.; Spreen, M. Art therapy with children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A review of clinical case descriptions on ‘what works’. Arts Psychother. 2014, 41, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Song, W.; Yang, M.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Effectiveness of music therapy in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 905113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isserow, J. Looking together: Joint attention in art therapy. Int. J. Art. Ther. 2008, 13, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.; Chiu, W.C. Joint Painting for Understanding the Development of Emotional Regulation and Adjustment Between Mother and Son in Expressive Arts Therapy. In Arts-Based Research, Resilience and Well-Being Across the Lifespan; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lith, T. Art therapy in mental health: A systematic review of approaches and practices. Arts Psychother. 2016, 47, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Grolnick, W.S.; La Guardia, J.G. The Significance of Autonomy and Autonomy Support in Psychological Development and Psychopathology. In Developmental Psychopathology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 795–849. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. Integrative emotion regulation: Process and development from a self-determination theory perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W. Teacher autonomy support reduces adolescent anxiety and depression: An 18-month longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Pérez, B.; Zuffianò, A. Children’s and Adolescents’ Happiness Conceptualizations at School and their Link with Autonomy Competence, and Relatedness. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkibi, H.; Ronen, T. Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction Mediates the Association between Self-Control Skills and Subjective Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, C.; Spreen, M.; Knorth, E.J. Exploring What Works in Art Therapy With Children With Autism: Tacit Knowledge of Art Therapists. Art. Therapy 2017, 34, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Spicer, L.; Wilson, M. Schema therapists’ perceptions of the influence of their early maladaptive schemas on therapy. Psychother. Res. 2022, 32, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, C.; Fisher, S. Do Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Share Fairly and Reciprocally? J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2714–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, K.M. Outcome-Based Evaluation of a Social Skills Program Using Art Therapy and Group Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum. Child. Sch. 2008, 30, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisvaser, S. Moving Along and Beyond the Spectrum: Creative Group Therapy for Children With Autism. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogindroukas, I.; Stankova, M.; Chelas, E.-N.; Proedrou, A. Language and Speech Characteristics in Autism. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. Volume 2022, 18, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sasson, A.; Gal, E.; Fluss, R.; Katz-Zetler, N.; Cermak, S.A. Update of a Meta-analysis of Sensory Symptoms in ASD: A New Decade of Research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4974–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chu, S.Y.; Lin, L.-Y. Emotion Dysregulation Mediates the Relationship Between Sensory Processing Behavior Problems in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Jia, Z.; Huang, X.; Lui, S.; Kuang, W.; Sweeney, J.A.; Gong, Q. Brain structural abnormalities in emotional regulation and sensory processing regions associated with anxious depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 94, 109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindle, K.; Moulding, R.; Bakker, K.; Nedeljkovic, M. Is the relationship between sensory-processing sensitivity and negative affect mediated by emotional regulation? Aust. J. Psychol. 2015, 67, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, G.; Fu, N.; Ben, Q.; Wang, L.; Bu, X. The effectiveness of music therapy in improving behavioral symptoms among children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1511920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, A.P.; de Vet, H.C.W.; de Bie, R.A.; Kessels, A.G.H.; Boers, M.; Bouter, L.M.; Knipschild, P.G. The Delphi List. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. Lancet 2025, 405, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieleninik, L.; Geretsegger, M.; Mössler, K.; Assmus, J.; Thompson, G.; Gattino, G.; Elefant, C.; Gottfried, T.; Igliozzi, R.; Muratori, F.; et al. Effects of Improvisational Music Therapy vs Enhanced Standard Care on Symptom Severity Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA 2017, 318, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.A.; Ioannou, S.; Key, A.P.; Coke, C.; Muscatello, R.; Vandekar, S.; Muse, I. Treatment Effects in Social Cognition and Behavior following a Theater-based Intervention for Youth with Autism. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2019, 44, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. Application of drama performance in intervention of children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Danub. 2022, 34, 909–913. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Tian, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Li, H. Improvement of symptoms in children with autism by TOMATIS training: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1357453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imankhah, F.; Hossein Khanzadeh, A.A.; Hasirchaman, A. The Effectiveness of Combined Music Therapy and Physical Activity on Motor Coordination in Children With Autism. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2018, 16, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, S.; Key, A.P.; Muscatello, R.A.; Klemencic, M.; Corbett, B.A. Peer Actors and Theater Techniques Play Pivotal Roles in Improving Social Play and Anxiety for Children With Autism. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, C.; Yao, C.; Ying, F. Effects of Auditory Integration Training Combined with Music Therapy on Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; IOS Press Ebooks: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mössler, K.; Schmid, W.; Aßmus, J.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Gold, C. Attunement in Music Therapy for Young Children with Autism: Revisiting Qualities of Relationship as Mechanisms of Change. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 3921–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeyron, T.; Robledo del Canto, J.-P.; Carasco, E.; Bisson, V.; Bodeau, N.; Vrait, F.-X.; Berna, F.; Bonnot, O. A randomized controlled trial of 25 sessions comparing music therapy and music listening for children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordanjani, S.R. Effectiveness of Drama Therapy on Social Skills of Autistic Children. Pract. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 9, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, S.; Gholami, H.A.Z. The effect of art therapy on motor skills of children with autism. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2021, 8, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sharda, M.; Tuerk, C.; Chowdhury, R.; Jamey, K.; Foster, N.; Custo-Blanch, M.; Tan, M.; Nadig, A.; Hyde, K. Music improves social communication and auditory–motor connectivity in children with autism. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; Goode, S.; Heemsbergen, J.; Jordan, H.; Mawhood, L.; Schopler, E. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. In PsycTESTS Dataset; APA PsycNet: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, D.A.; Arick, J.; Almond, P. Behavior Checklist for Identifying Severely Handicapped Individuals with High Levels of Autistic Behavior. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1980, 21, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopler, E.; Reichler, R.J.; DeVellis, R.F.; Daly, K. Childhood Autism Rating Scale. In PsycTESTS Dataset; APA PsycNet: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, M.; Petersen, G.; Vu, H.M.; Baudry, M.; Lynch, G. L-phenylalanyl-L-glutamate-stimulated, chloride-dependent glutamate binding represents glutamate sequestration mediated by an exchange system. J. Neurochem. 1987, 48, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J.N.; Davis, S.A.; Todd, R.D.; Schindler, M.K.; Gross, M.M.; Brophy, S.L.; Metzger, L.M.; Shoushtari, C.S.; Splinter, R.; Reich, W. Social Responsiveness Scale. In PsycTESTS Dataset; APA PsycNet: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, B.A.; Schupp, C.W.; Simon, D.; Ryan, N.; Mendoza, S. Elevated cortisol during play is associated with age and social engagement in children with autism. Mol. Autism 2010, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Rotatori, A.F.; Helsel, W.J. Development of a rating scale to measure social skills in children: The matson evaluation of social skills with youngsters (MESSY). Behav. Res. Ther. 1983, 21, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, D.V.M. The Children’s Communication Checklist—2; The Psychological Corporation: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, P.C.; Goes, T.C.; da Silva, L.C.F.; Teixeira-Silva, F. Trait vs. state anxiety in different threatening situations. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2017, 39, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, J.A.; Spirito, A.; McGuinn, M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000, 23, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S.S. Vineland adaptive behavior scales. In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2618–2621. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, W. The Lincoln-Oseretsky Motor Development Scale. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 1955, 51, 183–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gesell, A. Developmental schedules. In The Mental Growth of the Pre-School Child: A Psychological Outline of Normal Development from Birth to the Sixth Year, Including a System of Developmental Diagnosis; MacMillan Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1925; pp. 362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, D.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed.; (PPVT-4); Pearson: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schopler, E.; Lansing, M.D.; Reichler, R.J.; Marcus, L.M. Psychoeducational Profile: PEP-3: TEACCH Individualized Psychoeducational Assessment for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders; Pro-Ed: Austin, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2011, 2, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Parekh, S.; Hooper, L.; Loke, Y.; Ryder, J.; Sutton, A.; Hing, C.; Kwok, C.; Pang, C.; Harvey, I. Dissemination and publication of research findings: An updated review of related biases. Health Technol. Assess. 2010, 14, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.-W.; Song, F.; Vickers, A.; Jefferson, T.; Dickersin, K.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krumholz, H.M.; Ghersi, D.; van der Worp, H.B. Increasing value and reducing waste: Addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014, 383, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avrahami, D. Visual Art Therapy’s Unique Contribution in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. J. Trauma. Dissociation 2006, 6, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Music Therapy Association. What is Music Therapy? 2005. Available online: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- American Dance Therapy Association. What is Dance Therapy? 2025. Available online: https://www.adta.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Leather, J.; Kewley, S. Assessing Drama Therapy as an Intervention for Recovering Substance Users: A Systematic Review. J. Drug Issues 2019, 49, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for Poetry Therapy. Promoting Growth and Healing Through Language, Symbol, and Story. Available online: https://poetrytherapy.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- International Expressive Arts Therapy Association. What is Intermodal Expressive Arts? Available online: https://www.ieata.org/what-is-intermodal-expressive-arts/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

| Study Background | Participants | Aims | Intervention | Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Author (Year) | Region (s) | EXP n (% M) | CTRL n (% M) | Mean Age | Arts Modality + Components in EXP Group | Sessions | Length | Group vs. Individual | Theory | ASD Sx. (Overall) | Social | Psych. | Beh. | Physical | Language | Neuron Dev. | |

| 1 | Bieleninik, 2017 [47] | Multisite | 182 (94%) | 182 (81.9%) | 5.5 | Evaluate the effectiveness of improvisational music therapy in general social communication skills of children with ASD. | Improvisational music therapy vs. Enhanced standard care (ESC) Joint singing or musical instruments playing, and use of improvisation techniques such as synchronizing, mirroring, or grounding. | 60 sessions (high intensity) 30 sessions (Low IMT) | 5 mths | Individual led by qualified music therapist | NA | ✘ (ADOS-Social Affect; SRS) | ||||||

| 2 | Corbett, 2019 a [48] | USA | 44 (66.7%) | 33 (73.1%) | 10.9 | Evaluate the effectiveness of treatment in cooperative play and verbal interaction during peer interaction in children with ASD. | SENSE Theater vs. Waitlist control (WLC) Theater games, role playing, improvisation, and character development, while putting on a final play. | 10 | 10 weeks | Peer led Group | Social Learning Theory | ✔ (Sig. in Cooperative Play; PIP) | ✔ (Sig. in verbal ability; ToM-Verbal Interactions) | |||||

| 3 | Ding, 2022 [49] | China | 30 (NA) | 30 (NA) | -- | No Information. (Examine effectiveness of drama therapy in sleep quality and mental health in children with ASD.) | Drama Therapy vs. Treatment as usual (TAU) Drama performance. | NA | 3 mths | Group | Analytical psychology | -- | -- | ✔ (Sig, in Perceived pressure; CPSS) | ✔ (Sig. in Sleeping habit; CSHQ) | |||

| 4 | Fu, 2024 [50] | China | 15 (86.6%) | 15 (80%) | 6.9 | Examine effectiveness of TOMATIS training in improving autism- related symptoms in children with ASD. | TOMATIS vs. Music Listening Only Listening to 4 different pieces of music 1–2 times a day for 1–2 h with sound settings of different frequencies, strength of air conduction, bone conduction, and the processing time delay. | 2 (Each session lasted 10 days) | 27 days, divided into two 10 days sessions with 7 rest days | Individual led by TOMATIS trainers | Auditory Integration Theory | ✔ (CARS; ABC) | ||||||

| 5 | Imankhah, 2018 [51] | Iraq | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 6–11 | Explore the effect of music therapy along with physical activity on motor coordination behaviors of children with ASD. | Multimodality (Music therapy and movement) vs. Blank Control Using images for contact, eye contact, singing familiar songs, teaching rhythm through body movements, and engaging in balance board games and rhythmic motor games. | 15 | 7.5 week | Group led by Psychologists | NA | -- | -- | ✔ (Sig. in Motor Skills; LOMST) | ||||

| 6 | Ioannou, 2020 [52] | USA | 44 (66.7%) | 33 (73.1%) | 10.8 | Investigate the effectiveness of SENSE Theatre in enhancing social play and decreasing anxiety levels. | SENSE Theater vs. WLC Mock auditions, theater games, imaginative play, character development, role-play, and rehearsals; Video modeling for home practice; Public performances | 10 four-hour sessions (Daily) | 10 weeks | Group; with Trained peers | NA | ✔ (Sig. in group and self-play; PIP) | ✔ (Sig. In trait anxiety) ✘ (Non-Sig in state anxiety; STAI-C) | |||||

| 7 | Liu, 2024 [53] | China | 40 (70%) | 40 (62.5%) | 5.58 | Examine the effectiveness of Music Therapy with Auditory Integration Training (AIT) in the overall development of children with ASD. | Music Therapy + AIT vs. AIT only MT: Improvisational Performance, Instrument Selection, Instrumental Performance, and activities with peers. AIT: Oral training with pinyin imitation, vocalization using animated feedback, vocalization training, perceptual coordination by adjusting pitch, memory training by recalling previously learned sounds and interpreting silent animations. | 72 | 6 mths | Individual; led by music therapist | Auditory Integration Theory | ✔ (ABC) | ✔ (ATEC) | ✔ (Sig in. Language ability; PEP-3) | ✔ (GDS) | |||

| 8 | Mössler, 2020 [54] | Multisite | 50 (84%) | 51 (84%) | 5.4 | Examine the effectiveness of musical and emotional attunement in improving core ASD traits in children with ASD; and the relationship between therapy intensity and the level of attunement achieved. | Improvisational Music Therapy (High Intensity vs. Low intensity) Joint singing or musical instruments playing, and use of improvisation techniques such as synchronizing, mirroring, or grounding. | High intensity (max. 60 sessions) Low intensity (20 sessions) | 5 mths | Individual; led by qualified music therapist | NA | ✘ (AQR) | -- | |||||

| 9 | Rabeyron, 2020 [55] | France | 19 (87%) | 18 (87%) | 7.9 (0.79) | Examine the effectiveness of music therapy in improving clinical ASD symptoms in children with ASD. | Music Therapy vs. Music listening Only Playing instrumental and vocal music, Instrumental and vocal improvisation. | 25 (30 min per session) | 8 mths | Group; led by a music therapist, a co-therapist and clinical psychology trainee. | NA | ✔ (CGI; ABC) ✘ (CARS) | -- | -- | ||||

| 10 | Rahimi, 2021 b [56] | Iran | 20 (NA) | 20 (NA) | 10.03 (3.14) | Examine the effectiveness of drama therapy in enhancing the social skills dimensions of children with ASD. | Drama Therapy vs. TAU Stretching, memory exercises, group games, and five senses exercises, puppet shows, behavioral& participatory training, and animal play. Appling learned skills in previous sessions for social interactions. | 12 | 12 weeks | Group; Led by trained researchers & therapeutic assistants. | NA | -- | ✔ (MSSQ) | |||||

| 11 | Sabet, 2021 [57] | Iran | 15 (NA) | 15 (NA) | 6–12 | Examine whether painting-based art therapy can improve fine and gross motor skills among Children with ASD. | Painting-based art therapy vs. TAU Painting with contrasting colors, tearing and crumpling paper, working with pottery, making handicrafts, cutting lines with scissors, and purposeful coloring. | 18 | 6 weeks | Individual; led by Psychologist | NA | -- | -- | ✔ (Sig. in fine motor skills, balance; flexibility; LOMST) | ||||

| 12 | Sharda, 2018 [58] | Canada | 26 (80.8%) | 25 (88%) | 10.30 (1.91) | Investigate the effectiveness of a music-based intervention in improving social communication, and functional brain connectivity in school-age children with ASD. | Music Therapy vs. Treatment as usual Musical instruments, songs, and rhythmic cues to enhance communication, turn-taking, sensorimotor integration, social appropriateness, and musical interaction. | 8–12 | 8–12 weeks | Individual; led by accredited music therapist | Reward-based cortical modulation and sensoria-motor integration. | -- | ✔ (Sig. in prag. communication; CCC-2) ✘ (Non-sig. in social responsiveness; SRS) | ✘ (Non-sig. in mal-adaptive behavior; VABS) | ✘ (Non-sig. in vocab. reception; PPVT-4) | ✔ (Sig. in increasing brain connectivity) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, S.; Lai, A.H.Y.; Ho, H.W.H. The Effectiveness of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review of RCTs. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222960

Wei S, Lai AHY, Ho HWH. The Effectiveness of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review of RCTs. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222960

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Shijuan, Angel Hor Yan Lai, and Howard Wing Hong Ho. 2025. "The Effectiveness of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review of RCTs" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222960

APA StyleWei, S., Lai, A. H. Y., & Ho, H. W. H. (2025). The Effectiveness of Art Therapy on Children and Adolescents with ASD: A Systematic Review of RCTs. Healthcare, 13(22), 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222960

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)