Abstract

Background/Objectives: Social media has become a key activity in adolescents’ lives, with potential implications for their health and well-being. Because of this, the objective was to examine the influence of social media on the eating behavior and sleep quality of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years. Methods: The PubMed, Scopus, Proquest, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases were reviewed following the PRISMA protocol. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: a sample of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years without a baseline clinical diagnosis and research objectives related to social media and its influence on eating behavior or sleep quality. A total of 24 articles were included at the end of the search. Due to heterogeneity in measurement formats, a single pooled analysis was not feasible. Instead, two partial random-effects meta-analyses of continuous outcomes were performed (sleep and eating behaviours). Results: Qualitative synthesis revealed consistent associations between problematic social media use, poor sleep quality, and disordered eating. The meta-analyses showed a small-to-moderate and statistically significant association on sleep quality (r = 0.36) while the pooled estimate for eating behaviours was imprecise and not significant (r = 0.35), reflecting the very limited number of eligible studies. Conclusions: Excessive social media use is associated with poorer sleep and eating outcomes among adolescents. These findings highlight the need for educational and preventive strategies promoting healthy digital habits and psychological well-being. This systematic review elucidates the implications of social media use for health promotion at this development stage.

1. The Importance of Social Media Use in Adolescent Health

Social media use significantly influences aspects of adolescents’ psychological and physical development, as well as the construction of their identity.

It is important to understand the relationship adolescents have with social media, as it can have both positive and negative effects on their mental and physical health. The positive effects are related to increased social connection, greater access to information, and the creation of spaces that offer the opportunity to share new experiences, while the negative effects are related to addiction, a loss of control, cyberbullying, sleep disorders, and social comparisons, which are especially linked to body dissatisfaction.

2. Introduction

In recent years, social media use has grown exponentially among adolescents, becoming one of the most common activities in their daily lives [1]. Platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Facebook, and YouTube provide a space for socialization and identity building, where adolescents can both consume and create content [2].

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as the period between 10 and 19 years of age [3], the age range from 13 to 18 years is often considered a critical stage for social and emotional development, during which adolescents become especially sensitive to social feedback, peer approval, identity formation and mental health problems [4].

Social media provides an environment where adolescents can explore and express their identity, interact with their peers, and participate in various social activities [5]. However, continuous interaction can also lead to overexposure and dependence on social validation, affecting young people’s self-esteem and emotional well-being [4].

It is well known that intensive use of social media by adolescents is associated with some negative consequences for health and development in adolescence. According to the WHO HBSC report, 11% of adolescents exhibit problematic social media use, characterized by symptoms such as addiction (difficulty controlling their use and abandoning other activities in their daily lives). The same report and various studies highlight other risk factors such as social comparison, cyberbullying, less sleep quality, increased anxiety, and depressive symptoms [2,6].

Given these dynamics, it is necessary to further investigate the risk factors associated with social media use. Constant exposure can affect self-esteem and body image perception, which can lead to eating disorders [7], as well as anxiety and stress, factors that negatively affect sleep quality [8].

Furthermore, considering that both eating and sleeping share similar behavioural and psychological responses to factors such as stress, major life changes or social difficulties, it is important to examine adolescents’ habits related to nutrition and sleep [9]. Disruptions in either domain are often interrelated, as emotional distress or stressful experiences can lead to irregular eating patterns or sleep disturbances [10].

Therefore, from a health promotion perspective, it is necessary to consider the impact of social media use on adolescents, as well as to understand its relationship with eating habits and sleep quality at this stage of life. Based on these premises, this study aims to conduct a systematic review of the current scientific literature with the objective of examining the influence of social media on the eating behavior and sleep quality of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years.

3. Methods

This research was based on a systematic review following the PRISMA protocol [11]. The search protocol was registered in PROSPERO on 18 July 2025 (registration number CRD420251107338).

3.1. Research Question and Study Review Process

The research question was formulated following the participant, intervention, and outcome (PIO) structure, as follows: “What is the influence of social media use on the eating behavior and sleep quality of adolescents aged 13 to 18?” The research process included three phases: the initial database search (1), document screening in Covidence (2), and analysis of studies that met the inclusion criteria (3).

3.2. Search Strategy

Searches were conducted in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Proquest, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The MeSH terms “adolescence,” “social media,” “eating behavior,” and “sleep quality” were used, along with the descriptors “eating” and “sleeping,” in combination with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and “OR.” Time filters (2020–2025) or age filters (13 to 18 years) were used whenever this was an option within the search system. Specifically in PubMed, time filters were used to narrow down the results to the age range 13–18. Table 1 shows the search formulas plus the initial results.

Table 1.

Search formulas.

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Considering that social media platforms are highly dynamic and continuously evolving, all articles published between 1 January 2020, and 18 July 2025 were considered in order to capture the most recent and relevant evidence written in Spanish or English on the topic.

The eligible age range for inclusion was set between 13 and 18 years. However, studies including broader age ranges were also considered if they clearly reported separate findings for the adolescent subgroup or if their mean participant age fell within the 13–18 range, as these samples were deemed representative of the adolescent population.

Studies focusing on adolescents aged 13 to 18 years without a baseline clinical diagnosis (such as eating disorders or addiction to the Internet or social media) and that established research objectives related to social media and its influence on eating behavior or sleep quality were taken into account. While studies that included children or adults without separating the sample by age, that weren’t focused on the influence of social media use on eating behavior or sleep quality, or that had a sample of adolescents who were athletes or had psychiatric disorders or chronic diseases were excluded.

Regarding the type of study, qualitative studies and other systematic reviews or meta-analyses were excluded from this review. Qualitative articles were not considered relevant to the specific research question, as they did not provide quantitative data applicable to the outcomes of interest. In the case of systematic reviews or meta-analyses, their reference lists were examined to identify original studies meeting our inclusion criteria, and only those primary articles were incorporated when appropriate.

3.4. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists (JBI), with disagreements being resolved by a third reviewer [12]. The Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies Version 2 (ROBINS-I V2) tool was employed in order to evaluate the risk of bias at review level. This assessment allows for a consistent evaluation across different domains: study eligibility, identification and selection, data extraction and quality appraisal, as well as the synthesis and reporting of results [13]. The tool was applied independently and using a double-blind procedure.

3.5. Quantitative Synthesis (Meta-Analysis)

A single pooled meta-analysis was not feasible due to variability in the measurement instruments and outcomes across studies. Therefore, in addition to the qualitative synthesis, two partial random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to quantify the association between social media use and adolescent health outcomes.

Analyses were conducted by grouping studies into two domains (sleep and eating), only for studies that reported continuous outcomes allowing the computation of correlation coefficients. All analyses were performed using JASP (version 0.19, University of Amsterdam) [14], under the Classical Meta-Analysis module, applying a Der Simonian–Laird random-effects model.

Effect sizes were expressed as Pearson’s r, and correlations for analysis were Fisher z-transformed and back-transformed for interpretation. Effect sizes were extracted directly from the original studies or derived from verifiable numerical results following standard meta-analytic procedures.

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q, τ2, and I2 statistics, and publication bias was explored through residual funnel plots and leave-one-out diagnostics.

4. Results

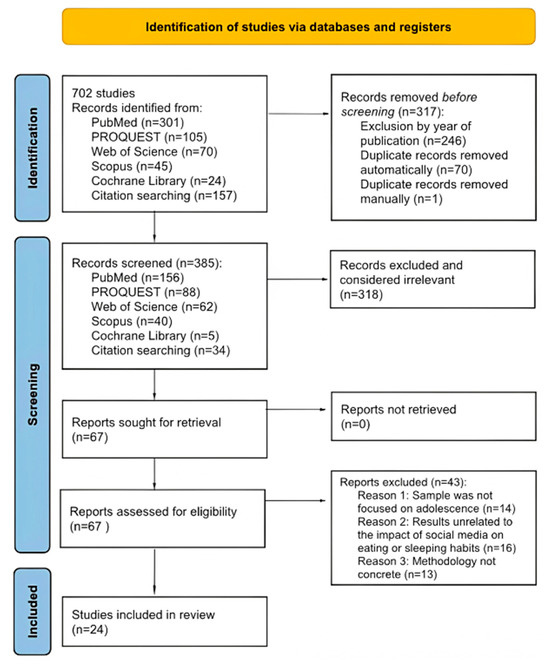

Throughout the process, decisions regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies were verified by two members of the research team. A total of 702 records were identified through database searches. Out of this initial number, 246 studies were excluded for having been published more than five years ago and 71 duplicates were identified. This resulted in 385 articles being examined by title and abstract, of which 318 studies were excluded. Finally, 67 full-text articles were analysed, of which 43 were excluded for the following reasons: having a child or adult sample (n = 14), not focusing on the impact of social media on eating habits or sleep quality (n = 16), or not having a methodology design appropriate for the research objective (n = 13). More detailed information on this process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for systematic reviews. Note: Resource extracted from Page MJ et al. [15]. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ URL (accessed on 22 July 2025).

4.1. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Table 2 and Table 3 show the characteristics of the 24 studies included in this study. Of the 24 studies, 9 investigated the impact of social media on eating habits [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], while 14 focused on sleep quality [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and only 1 study included both health factors [39]. The tables represent these findings in a separate manner, classified by studies that focused on eating behaviours (Table 2) and studies that focused on sleep quality (Table 3). The study that included both health factors appears on both tables with separate findings.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the selected studies that focused on eating behaviours. (n = 10).

Table 3.

Main characteristics of the selected studies that focused on sleep quality (n = 15).

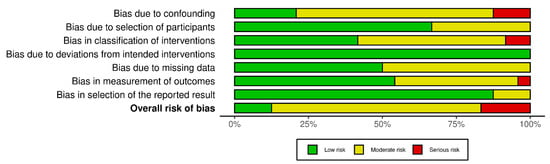

Using the ROBINS-I V2 tool, an overall consensus of 85.11% was reached among the three reviewers, with most studies being rated as having a moderate overall risk of bias [13] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment. Note: This figure was produced employing the ROBINS-I V2 assessment tool [13].

4.2. Qualitative Synthesis: Social Media Use and Platforms Effect on Health

During adolescence, social media use is higher than among the adult population [16]. In some cases, it accounts for more than half of the day [17] making it very difficult to limit time spent on these platforms [18].

Khan et al. conducted a study involving 40 countries and found that all participants used social media, with women using it more frequently [20]. Meanwhile, Maksniemi et al. found that the younger the adolescents, the greater the difficulties in managing time online, suggesting that this population is particularly vulnerable in their social media use [38].

Several studies found specific relationships that affect health associated with the use of particular social platforms: TikTok use is associated with lower well-being, reduced academic participation, and procrastination in going to sleep [21], night time use of YouTube affects sleep quality [22], intensive use of Instagram causes eating problems [23], and use of Facebook or Snapchat causes sleep disturbances [18,24]. However, the main factor determining the impact of social media use on health is not related to the platform, but the content to which the adolescent is exposed [24,39]. Therefore, it is essential to analyze the content that is viewed within each social platform.

4.2.1. Impact of Social Media on Eating Habits

The studies included emphasize that social media influences eating habits through multiple factors. Among the most common associations, it has been observed that social media use encourages more restrictive eating behaviours such as avoiding new foods, reducing or eliminating fruit and vegetable consumption, avoiding foods due to fear of expiration dates, and skipping meals [25,26]. Likewise, social media use has been linked to increased consumption of less healthy foods, preferences for fast food, and high consumption of sugary drinks, soft drinks, or caffeine [26,39].

Multiple studies have found an association between social media use and a higher likelihood of suffering from eating disorders [16,23,31,32,33,34], being more relevant in secondary school students than in adult populations [16]. No differences have been found with regard to gender, as both are affected similarly [31,34], although some studies have found a higher probability in women [22], and others in men [16].

4.2.2. Impact of Social Media on Sleep Quality

Problematic and continuous use of social media has been associated with poorer sleep quality [18,20,21,22,24,35,36,37,38]. In addition, these platforms were associated with shorter sleep duration, nightmares, insomnia, difficulty falling asleep, and going to bed later [17,27,36]. Adolescents’ daily functioning was also affected, manifesting as daytime sleepiness, fatigue, emotional exhaustion, behavioural and emotional problems, conflicts with peers, and attention difficulties [19,38].

4.2.3. Risk and Protective Factors for Social Media Use in Adolescence

In addition to analysing the prevalence and types of problems associated with social media that relate to eating and sleeping problems in adolescents, the included studies highlight that the origin of risk and protective factors is multifactorial, encompassing personal, social, and emotional aspects.

4.2.4. Risk Factors for Social Media Use

Firstly, heavy use of social media was described as the most worrying risk factor in adolescents [18,20,21,23,26,31]. Although some studies conclude that time spent online is not associated with problems that interfere with adolescents’ daily lives [20,37], frequent use of these platforms is considered the beginning of problematic behavior, so the amount of time spent using them should be considered a warning sign [26,28,36].

Secondly, the social environment is considered another important factor [22,38,40]. Poor relationships with family/friends that encourage social comparisons increase the likelihood of health problems related to social media use [23,29]. Similarly, low self-esteem is associated with both sleep and eating problems [28,29,32].

In eating disorders, these risks include: obsessive thoughts about physical appearance [29,34], the need to edit photos before posting them [16], restrictive diets inspired by online content, overexposure to unhealthy eating information [33,39], and social interaction dependence through social media platforms [33].

With regard to sleep, the associated risk factors are: not turning off mobile devices before bed [38], high use of social media during day and night [17,24], and poor academic performance, which could be considered both a cause and a consequence of problematic social media use [21,30].

4.2.5. Protective Factors for Social Media Use

To prevent harmful use of social media from affecting eating and sleeping habits, it is essential to promote a series of protective factors mentioned in the studies:

Firstly, it’s recommended to use social media platforms and the Internet for less than 5 h a day [29,36], avoiding night time use and establishing parental restrictions [37]. Secondly, training in emotional management is recommended, as continued use of social media can cause symptoms of anxiety and stress and the need to be constantly connected, so it is essential to learn to control these feelings to facilitate participation in other activities [31]. Thirdly, acquiring adequate digital skills will promote the ability to self-regulate the content consumed on social media, as well as self-reflection and solid self-esteem [29,32], which can reduce the presence of eating and sleeping problems by acquiring the ability to separate the digital world from the personal world [19,31]. Finally, promoting a quality social environment in which adolescents feel supported and can participate in various activities will reduce harmful use of social media [33,38].

4.3. Quantitative Synthesis: Meta-Analysis Results

A single pooled meta-analysis was not feasible due to substantial variability in measurement instruments and outcome formats across studies. Therefore, two partial random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to quantify the association between social media use and adolescent health outcomes in the domains of sleep and eating behaviours, using only studies that reported continuous outcomes from which correlation coefficients could be derived.

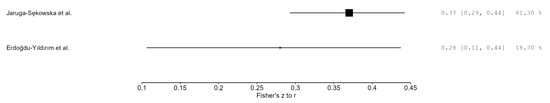

- Eating (continuous outcomes): Jaruga-Sękowska, 2025 [16]; Erdoğdu Yıldırım, 2025 [21].

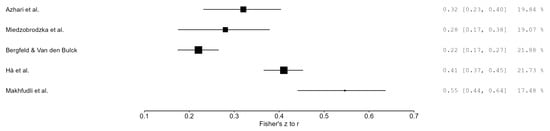

- Sleep (continuous outcomes): Azhari et al. (2022) [34]; Miedzobrodzka et al. (2024) [33]; Bergfeld & Van den Bulck (2021) [35]; Hà et al. (2023) [32]; Makhfudli et al. (2020) [29].

In the eating behavior domain, the random-effects model showed a pooled correlation of r = 0.35, with a wide confidence interval (95% CI: –0.13 to 0.70, p = 0.067), indicating no statistically significant association between social media use and eating-related outcomes. Between-study heterogeneity was not detectable (Q(1) = 0.97, p = 0.326; I2 = 0%), although the precision of these estimates is limited due to the very small number of included studies (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of correlations between social media use and disordered eating indicators (random-effects model) [16,21]. Note: Each square represents an individual study, and the diamond indicates the pooled effect size (r), with 95% confidence intervals.

Regarding sleep quality, higher social media use was moderately associated with poorer sleep quality across the five studies reporting continuous sleep indicators. The meta-analysis yielded a pooled effect of r = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.51, p = 0.005, with high heterogeneity (I2 = 92.07%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of correlations between social media use and sleep quality (random-effects model) [29,32,33,34,35]. Note: Each square represents an individual study, and the diamond indicates the pooled effect size (r), with 95% confidence intervals.

5. Discussion

Adolescence is a crucial stage in development, characterized by a multitude of physical, psychological, and social changes that can have lasting repercussions on health and well-being. When problems arise during this period and are not addressed appropriately, the transition to adulthood can be compromised. In this context, it is essential to analyse the factors that influence adolescent health, among which the use of social media has become increasingly relevant [41,42].

The present review aimed to answer the following question: “What is the influence of social media use on the eating behavior and sleep quality of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years?”. The results indicate that social media use represents a challenge in intervention with major implications for the health and well-being of adolescents. The quantitative synthesis included only analyses based on continuous correlations due to heterogeneity in how outcomes were reported across studies. The meta-analysis of sleep quality revealed a small-to-moderate and statistically significant association, suggesting that more frequent or intensive social media use is reliably linked to poorer sleep quality across diverse adolescent samples. This result aligns with theoretical expectations related to sleep displacement, emotional arousal, and nighttime screen exposure, and indicates that sleep may be one of the most consistently affected health domains.

In contrast, the evidence regarding eating-related outcomes was much more limited. Although the pooled effect size was numerically similar, the confidence interval was wide and included zero, and only two studies met criteria for inclusion. Consequently, this association cannot be interpreted as reliable or robust. Instead, these results highlight a promising but currently inconclusive pattern that requires further research with standardized measures and larger samples.

Together, these findings suggest that while sleep disruptions appear to be a more firmly established correlate of adolescent social media use, the relationship with eating behaviours remains preliminary. Future studies should aim to harmonize measurement approaches and report sufficient statistical details to enable more comprehensive meta-analytic evaluations.

On the other hand, on the qualitative synthesis, evidence from large-scale population-based studies corroborates the patterns observed in smaller-scale investigations. For instance, both pan-European and Japanese studies involving tens of thousands of participants report associations consistent with those found in smaller, school-based or regional samples, suggesting that the observed relationships are not merely artifacts of limited sample sizes or local contexts [26,36].

Moreover, potential cultural differences should be acknowledged. Across diverse countries, girls generally report slightly higher social media use than boys, along with somewhat greater sleep-related difficulties, characteristics that may reflect broader sociocultural norms and gendered expectations surrounding technology use and well-being and that may have become more prevalent since the collective increase in mental health problems in adolescents of these last few years [43].

Nevertheless, it is important to consider that the observed associations between social media use, sleep quality, and eating behaviours may be partially influenced by additional variables that were not consistently controlled across studies. Several studies did not adjust for relevant confounders such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, BMI, socioeconomic status, parental supervision, or nighttime screen exposure, all of which are known to affect sleep and eating patterns in adolescents. In addition, the included studies were conducted in diverse cultural contexts across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and South America, where cultural norms regarding body image, family routines, and technology use differ. Therefore, contextual and psychosocial factors may modulate the strength of the association. However, despite variability in confounding control and cultural context, all studies consistently showed the same direction of association.

Although the use of social media can have a positive impact on adolescence by facilitating social contact, promoting independence in seeking information, and developing creativity [44], the main finding of this systematic review was that social media affects eating habits and sleep quality due to factors such as time spent using it, platform content, and social influence.

5.1. Eating Habits

In relation to food, other studies have confirmed that multiple factors, such as food price, taste, product availability, social context, peer group relationships and influence, and exposure to online content, condition the acquisition of eating habits [45]. Intensive and continuous use of social media has been associated with low self-esteem, increased social comparison, and pressure to acquire an idealized body image, sometimes through the use of filters or digital retouching [11]. These dynamics favour the emergence of risky eating behaviours, which could lead to the development of an eating disorder, as well as the development of unhealthy eating habits such as skipping breakfast, consuming sugary drinks and fast food, and reducing vegetables and fruit intake [21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Taking into account the impact social media has on eating habits, some recommendations in order to promote adolescents’ health could be as follows:

- Maintain regular meal times and avoid eating in front of screens.

- Involve adolescents in food preparation to strengthen their connection to real food.

- Promote a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables and proteins, avoiding excessive consumption of ultra-processed foods or caffeinated drinks.

- Recognition of the emotional impact of digital content (social comparisons, likes, beauty filters, etc.).

5.2. Sleep Quality

Sleep has been extensively studied, concluding that adequate rest is beneficial for strengthening cognitive skills and emotional well-being in adolescence [46]. However, it has been shown that sleep quality is poorer when social media is used at night, as well as when it is used under pressure to stay constantly connected [17,24]. This situation affects academic performance, causes emotional exhaustion and daytime sleepiness, thus increasing the risk of mental health problems [47].

Considering the impact social media has on sleep quality, some recommendations in order to promote adolescents’ rest are:

- Set a “disconnection hour” at least 30–60 min before bed without screens.

- Establish a consistent sleep routine leaving the phone outside the bedroom or in airplane mode overnight.

- Replace night scrolling with soothing activities (reading, listening to soft music, breathing exercises).

- Identify whether they wake up due to notifications or feel compelled to check social media.

5.3. Recommendations for Health in Adolescence

The implications of these findings are wide-ranging. On the one hand, they confirm that continued use of social media can be a significant risk factor for adolescents’ overall health, hindering participation in other activities and the formation of social bonds. Studies agree that adolescents’ vulnerability increases due to high exposure to content and social exposure online [48,49].

From a clinical perspective, these results suggest a series of protective factors and recommendations for health promotion, including age restrictions for access to platforms, parental controls on mobile devices, digital education for adolescents, and the importance of community spaces that encourage activities to strengthen personal and interpersonal relationships outside online platforms.

In the educational and healthcare fields, professionals should pay attention to how adolescents use social media to obtain early indicators of possible eating and sleeping disorders.

Some actionable steps that could be taken in order to address this social problem from a preventive approach could be:

- 1.

- Regulation and control access to social media: implementing measures that encourage responsible and conscious use of social media.

- 2.

- Promotion of healthy eating and sleeping habits: educating adolescents about self-care and helping them understand the importance of nutrition and rest.

- 3.

- Digital education and emotional literacy: covering aspects such as developing critical evaluation skills of online information or online safety limits.

- 4.

- Encouraging healthy community and social spaces: coordinating efforts to create healthy environments that reinforce a sense of belonging, cooperation and well-being.

- 5.

- The role of professional support: mental health and primary care professionals, along with families, play a key role in the early detection of problematic social media use. Some warning signs to watch for include sudden weight changes or excessive concern with appearance for eating habits and frequent complaints of tiredness or poor academic performance for sleep quality.

For this reason, it is recommended that prevention programs be implemented in schools, colleges, universities, health centers, community spaces, leisure and sports clubs, etc., including activities related to digital literacy, emotional self-regulation, and strengthening self-esteem.

With regard to public policy, the results obtained point to the importance of including awareness campaigns on the risks of excessive use of social media and the impact of different types of online content on adolescents.

Finally, as possible lines of future research, the need to conduct more in-depth longitudinal studies to explore differences between platforms and content over time has been identified, as well as preventive interventions aimed at strengthening digital health in adolescence.

6. Limitations

Most of the included studies have a cross-sectional design (n = 20), which may influence our understanding of the impact of social media use on eating habits and sleep quality in adolescents over time. The inclusion of additional databases, the review of grey literature, or the expansion of the search to encompass studies published in a broader range of languages could further improve the scope and comprehensiveness of this systematic review.

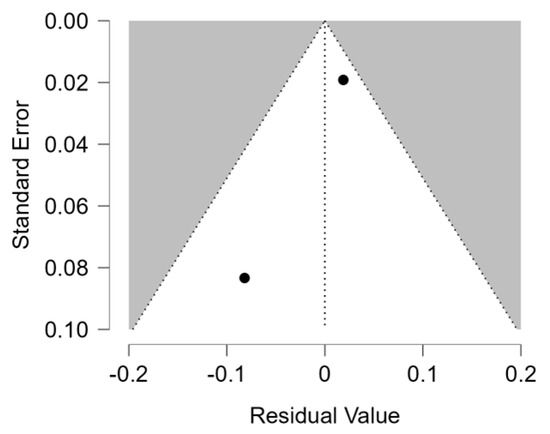

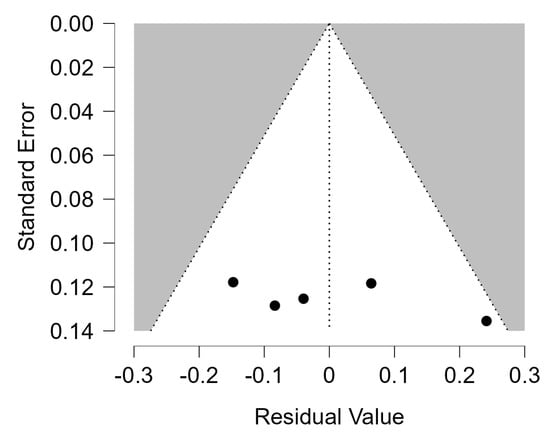

Although two partial meta-analyses were performed, it was not possible to include all studies in a single quantitative synthesis due to the diversity of measures and outcomes. Moreover, the number of studies included in each partial meta-analysis was small (2–4 studies), which limits the precision of the pooled estimates and the assessment of publication bias. Only studies reporting continuous outcomes that allowed the computation of correlation coefficients were included quantitatively. Several potentially relevant studies could not be incorporated into the meta-analyses due to heterogeneity in outcome formats or lack of extractable numerical data, which may reduce the comparability of findings.

Moreover, high heterogeneity was observed in the sleep meta-analysis, indicating that results may vary meaningfully depending on the operationalization of social media use and sleep constructs. The very small number of included studies, especially in the eating domain, also limits the assessment of publication bias: with only two studies, funnel plots and influence diagnostics cannot be reliably interpreted, and even in the sleep domain, high heterogeneity complicates their evaluation.

While self-reported measures were used across studies, many relied on validated standardized instruments (e.g., EAT-26, SCOFF, PSQI), which reduces measurement bias. However, control of confounding variables was inconsistent. Some studies adjusted for relevant covariates (e.g., age, sex, BMI, socioeconomic status, mental health), whereas others performed only bivariate analyses without multivariable adjustment. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, important confounders such as parental supervision, nighttime screen use, and psychological distress were frequently not considered, which may lead to an over- or underestimation of the true associations.

Furthermore, studies were conducted across heterogeneous cultural contexts (Asia, Europe, Middle East, North and South America). Cultural norms regarding social media use, body image, family routines, and sleep hygiene differ substantially, which may moderate the strength and direction of the associations and limit cross-context generalizability.

7. Conclusions

Problematic social media use during adolescence poses a significant challenge to mental health and well-being at this stage of development. The studies reviewed provide a comprehensive overview of the risk factors, impact, and consequences of using these platforms during adolescence.

While further research into this phenomenon is essential in order to design more effective intervention strategies tailored to the specific characteristics of different groups of adolescents, the relationship between social media and eating disorders or sleep quality should be considered a priority area for research and preventive interventions. Addressing these issues could help mitigate the long-term negative effects on young people’s health. The results from the meta-analyses specially show the need for more research focused on how social media affects eating behaviours.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13222962/s1. Table S1: Summary of confounding control and cultural context across all included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-H. and S.C.-L.; methodology, A.C.-H., A.C.-G., S.C.-L. and O.I.F.-R.; literature research, A.C.-H., A.C.-G. and S.C.-L.; study selection, A.C.-H., A.C.-G. and S.C.-L.; quantitative analysis (meta-analyses), O.I.F.-R.; data curation, ACH, A.C.-G., S.C.-L. and O.I.F.-R.; quality evaluation, A.C.-H., A.C.-G. and O.I.F.-R.; validation, A.C.-H., A.C.-G. and O.I.F.-R.; formal analysis, A.C.-H. and A.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-H. and A.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-H., A.C.-G. and O.I.F.-R.; supervision, O.I.F.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Complementary Tables

This material contains the detailed statistical output of the two partial random-effects meta-analyses described in Section 4.3. of the main manuscript.

Table A1.

Results of the random-effects meta-analysis (Der Simonian–Laird method) for disordered eating (continuous outcomes).

Table A1.

Results of the random-effects meta-analysis (Der Simonian–Laird method) for disordered eating (continuous outcomes).

| Disordered Eating (Continuous Outcomes) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | 95% PI Lower | 95% PI Upper | p |

| Pooled effect (r) | 0.354 | −0.129 | 0.701 | −0.129 | 0.701 | 0.067 |

| τ (tau) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.272 | — | — | — |

| τ2 (tau-squared) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 5.162 | — | — | — |

| I2 (%) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 99.898 | — | — | — |

Note. Correlations were Fisher z-transformed before analysis and back-transformed for interpretation.

Table A2.

Results of the random-effect meta-analysis (Der Simonian-Laird method) for sleep quality (continuous outcomes).

Table A2.

Results of the random-effect meta-analysis (Der Simonian-Laird method) for sleep quality (continuous outcomes).

| Sleep Quality (Continuous Outcomes) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | 95% PI Lower | 95% PI Upper | p |

| Pooled effect (r) | 0.355 | 0.186 | 0.505 | −0.036 | 0.652 | 0.005 |

| τ (tau) | 0.131 | 0.072 | 0.433 | — | — | — |

| τ2 (tau-squared) | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.187 | — | — | — |

| I2 (%) | 92.073 | 77.820 | 99.218 | — | — | — |

Note: The pooled correlation coefficient (r) was obtained under a Der Simonian–Laird random-effects model using Fisher’s z transformation.

Appendix A.2. Complementary Figures

This material contains more detailed statistical output of the two partial random-effects meta-analyses described in Section 4.3. of the main manuscript.

Figure A1.

Residual funnel plot for meta-analysis of correlations between social media use and disordered eating indicators. Note. Each point represents an individual study; no marked asymmetry was observed.

Figure A2.

Residual funnel plot for the meta-analysis of correlations between social media use and sleep quality. Note. Each point represents a study; the vertical line corresponds to the pooled effect size, and the dashed lines indicate pseudo 95% confidence limits.

This material forms an integral part of the main publication and follows the PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines [15].

References

- Guinta, M.R.; John, R.M. Social Media and Adolescent Health. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 44, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chassiakos, Y.L.R.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Media, C.O.N.C.A.N.D.; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; et al. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media on Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, V. Social Media: A Digital Social Mirror for Identity Development during Adolescence. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 22170–22180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M.P.; Newton, A.S.; Chisholm, A.; Shulhan, J.; Milne, A.; Sundar, P.; Ennis, H.; Scott, S.D.; Hartling, L. Prevalence and Effect of Cyberbullying on Children and Young People: A Scoping Review of Social Media Studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanzari, C.M.; Gorrell, S.; Anderson, L.M.; Reilly, E.E.; Niemiec, M.A.; Orloff, N.C.; Anderson, D.A.; Hormes, J.M. The Impact of Social Media Use on Body Image and Disordered Eating Behaviors: Content Matters More than Duration of Exposure. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, L.H.; Dollar, J.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; Shanahan, L.; Wideman, L. Emotional Eating in Adolescence: Effects of Emotion Regulation, Weight Status and Negative Body Image. Nutrients 2021, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, M.; Bacaro, V.; Natale, V.; Tonetti, L.; Crocetti, E. The Longitudinal Interplay between Sleep, Anthropometric Indices, Eating Behaviors, and Nutritional Aspects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.L.; Triplett, O.M.; Morales, N.; Van Dyk, T.R. Associations Among Sleep, Emotional Eating, and Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute, J.B. Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies; Joanna Briggs Institute: North Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.; Higgins, J.; Hernán, M.; Reeves, B.; Savović, J.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions, Version 2 (ROBINS-I V2). 2024. Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/social-community-medicine/images/centres/cresyda/ROBINS-I_detailed_guidance.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Love, J.; Selker, R.; Marsman, M.; Jamil, T.; Dropmann, D.; Verhagen, A.J.; Ly, A.; Gronau, Q.; Šmíra, M.; Epskamp, S.; et al. JASP: Graphical Statistical Software for Common Statistical Designs. J. Stat. Softw. 2019, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaruga-Sękowska, S.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Woźniak-Holecka, J. The Impact of Social Media on Eating Disorder Risk and Self-Esteem Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Psychosocial Analysis in Individuals Aged 16–25. Nutrients 2025, 17, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Shin, K. How Does Adolescents’ Usage of Social Media Affect Their Dietary Satisfaction? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Jang, H.; Oh, H. Smartphone Usage Patterns and Dietary Risk Factors in Adolescents. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2109–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Hawes, T.; Scott, R.A.; Campbell, T.; Webb, H.J. Adolescents’ Online Appearance Preoccupation: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study of the Influence of Peers, Parents, Beliefs, and Disordered Eating. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.J.; Kim, D.B.; Ko, J.; Lim, J.H.; Park, E.-C.; Shin, J. Association between Watching Eating Shows and Unhealthy Food Consumption in Korean Adolescents. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdodu Yildirim, A.B.; Gündogdu, Ü.; Eroglu, M. Myths Regarding Gender Differences in Eating Disorders in Adolescents. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2025, 36, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livet, A.; Boers, E.; Laroque, F.; Afzali, M.H.; McVey, G.; Conrod, P.J. Pathways from Adolescent Screen Time to Eating Related Symptoms: A Multilevel Longitudinal Mediation Analysis through Self-Esteem. Psychol. Health 2024, 39, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieiro, P.; González-Rodríguez, R.; Domínguez-Alonso, J. Self-Esteem and Socialisation in Social Networks as Determinants in Adolescents’ Eating Disorders. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4416–e4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, A.R.; Bussey, K.; Fardouly, J.; Griffiths, S.; Murray, S.B.; Hay, P.; Mond, J.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. Protect Me from My Selfie: Examining the Association between Photo-Based Social Media Behaviors and Self-Reported Eating Disorders in Adolescence. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, K.; Chen, S.; Rothmann, S.; Dhir, A.; Pallesen, S. Investigating the Relation among Disturbed Sleep Due to Social Media Use, School Burnout, and Academic Performance. J. Adolesc. 2020, 84, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Thomas, G.; Karatela, S.; Morawska, A.; Werner-Seidler, A. Intense and Problematic Social Media Use and Sleep Difficulties of Adolescents in 40 Countries. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, N.E.; Santoro, E.; Lugo, A.; Madrid-Valero, J.J.; Ghislandi, S.; Torbica, A.; Gallus, S. The Role of Technology and Social Media Use in Sleep-Onset Difficulties Among Italian Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e20319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümen, A.; Evgin, D. Social Media Addiction in High School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Its Relationship with Sleep Quality and Psychological Problems. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 2265–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhfudli; Nastiti, A.A.; Pratiwi, A. Relationship Intensity of Social Media Use with Quality of Sleep, Social Interaction, and Self-Esteem In Urban Adolescents In Surabaya. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 783–788. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.H.; Al-Shatari, S.A.E. The Impact of Using the Internet and Social Media on Sleep in a Group of Secondary School Students from Baghdad. AL-Kindy Coll. Med. J. 2023, 19, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaveepojnkamjorn, W.; Srikaew, J.; Satitvipawee, P.; Pitikultang, S.; Khampeng, S. Association between Media Use and Poor Sleep Quality among Senior High School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. F1000Research 2021, 10, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hà, T.A.; Tran, M.A.Q.; Lin, C.-Y.; Nguyen, Q.L. Facebook Addiction and High School Students’ Sleep Quality: The Serial Mediation of Procrastination and Life Satisfaction and the Moderation of Self-Compassion. J. Genet. Psychol. 2023, 184, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedzobrodzka, E.; Du, J.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M. TikTok Use versus TikTok Self-Control Failure: Investigating Relationships with Well-Being, Academic Performance, Bedtime Procrastination, and Sleep Quality. Acta Psychol. 2024, 251, 104565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A.; Toms, Z.; Pavlopoulou, G.; Esposito, G.; Dimitriou, D. Social Media Use in Female Adolescents: Associations with Anxiety, Loneliness, and Sleep Disturbances. Acta Psychol. 2022, 229, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergfeld, N.S.; Van den Bulck, J. It’s Not All about the Likes: Social Media Affordances with Nighttime, Problematic, and Adverse Use as Predictors of Adolescent Sleep Indicators. Sleep Health 2021, 7, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, Y.; Kaneita, Y.; Itani, O.; Matsumoto, Y.; Jike, M.; Higuchi, S.; Kanda, H.; Kuwabara, Y.; Kinjo, A.; Osaki, Y. The Association between Internet Usage and Sleep Problems among Japanese Adolescents: Three Repeated Cross-Sectional Studies. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Geurts, S.M.; Ter Bogt, T.F.M.; van der Rijst, V.G.; Koning, I.M. Social Media Use and Adolescents’ Sleep: A Longitudinal Study on the Protective Role of Parental Rules Regarding Internet Use before Sleep. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksniemi, E.; Hietajärvi, L.; Ketonen, E.E.; Lonka, K.; Puukko, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Intraindividual Associations between Active Social Media Use, Exhaustion, and Bedtime Vary According to Age-A Longitudinal Study across Adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Chen, S.; Jiménez-López, E.; Abellán-Huerta, J.; Herrera-Gutiérrez, E.; Royo, J.M.P.; Mesas, A.E.; Tárraga-López, P.J. Are the Use and Addiction to Social Networks Associated with Disordered Eating Among Adolescents? Findings from the EHDLA Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 22, 3775–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, A.; Nehra, R.; Sahoo, S.; Grover, S. Prevalence of Loneliness and Its Correlates among Patients with Schizophrenia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, J.S.; Doshmangir, L.; Khoshmaram, N.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Abdolahi, H.M.; Khabiri, R. Key Factors Affecting Health Promoting Behaviors among Adolescents: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, W. The Research on Risk Factors for Adolescents’ Mental Health. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, I.; Majumder, J.; Bagepally, B.S.; Ray, S.; Saha, A.; Chakrabarti, A. Burden of Mental Health Disorders and Synthesis of Community-Based Mental Health Intervention Measures among Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic in Low Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 89, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, A.; Ward, N.; Yu, R.; O’Dea, N. Positive Effects of Digital Technology Use by Adolescents: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, A.N.; O’Sullivan, E.J.; Kearney, J.M. Considerations for Health and Food Choice in Adolescents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, G.M.; Lokhandwala, S.; Riggins, T.; Spencer, R.M.C. Sleep and Human Cognitive Development. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 57, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattu, V.K.; Manzar, M.D.; Kumary, S.; Burman, D.; Spence, D.W.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. The Global Problem of Insufficient Sleep and Its Serious Public Health Implications. Healthcare 2019, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, M.; Wright, M.; Naslund, J.; Miers, A.C. How Technology Use Is Changing Adolescents’ Behaviors and Their Social, Physical, and Cognitive Development. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16466–16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orben, A.; Meier, A.; Dalgleish, T.; Blakemore, S.-J. Mechanisms Linking Social Media Use to Adolescent Mental Health Vulnerability. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 3, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).