The Use of Infographics to Inform Infection Prevention and Control Nursing Practice: A Descriptive Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Background

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Data Awareness

3.1.1. Importance of Data Awareness

They are important (referring to data) because they make us reflect on our practices (…) if we see that the results are not so good, it might lead us to reflect that we, as professionals of an institution, may need to do better (…). Bringing it out to the open, for awareness, I think it leads us to that, to reflection.(P1)

I think it has everything to do with awareness, because the more we know, the more we become aware.(P12)

With this data we have tools to try and make a difference, to improve, for the coming years. Because we know where we have been, where we are, and where we want to go. And with this kind of documents, we can understand our evolution.(P2)

I think that only data makes us change the way we work, to improve (…) What can be changed? That’s the importance (…) it kind of brings us back to reason.(P6)

They are important (referring to data) because they are evidence that either we are doing things correctly in terms of practice care, or, really, something is failing in our practice (…) the connection between practice and evidence ends up being demonstrated through the results.(P11)

3.1.2. Dissemination Methodologies

Between having a report with 20 or 30 pages, and having an infographic, I think it’s much easier to see something that is simple and explicit than, for example, going to the compute or flipping through a document... you know, you lose some time reading. One thing is having a report (…) another thing is having the information in a strategic place where you can go and see the information.(P1)

The information gets to the ward, but then, (…) the way it is shared with the team, the one’s that really matter… well, it is said: ‘There is information on the intranet, check it out because these data are important for you to see’. Given the workload people have, and sometimes even their interest, not everyone does it (check the intranet), obviously.(P13)

(…) less time-consuming for nurses, because they don’t have to go through a document with many pages (…) here (referring to the infographic) we have all the information, organized, easy to interpret, and then it’s easy to pass it on to others, to peers.(P2)

(...) that’s when the information really reached us, because until then, maybe the data was available, but we wouldn’t go looking for it, and there was no visibility. And this way, it came to us.(P3)

(…) the way the results are shown to the teams, through images. That is important. In the past, it was just the written report that was sent, and there you go, sometimes it didn’t get to the team. It was difficult.(P13)

3.1.3. Data Awareness Impact

(…) for knowing that there was an increase in central venous catheter associated infections, it even led me to do more research on the topic (…) it kind of pushed me to look into it, to update myself.(P1)

The fact that I saw the incidence of urinary tract infection in our hospital made me rethink this practice and what needs to be changed to improve this infection rate. Because being in practice, I see the complications this brings to the patients.(P7)

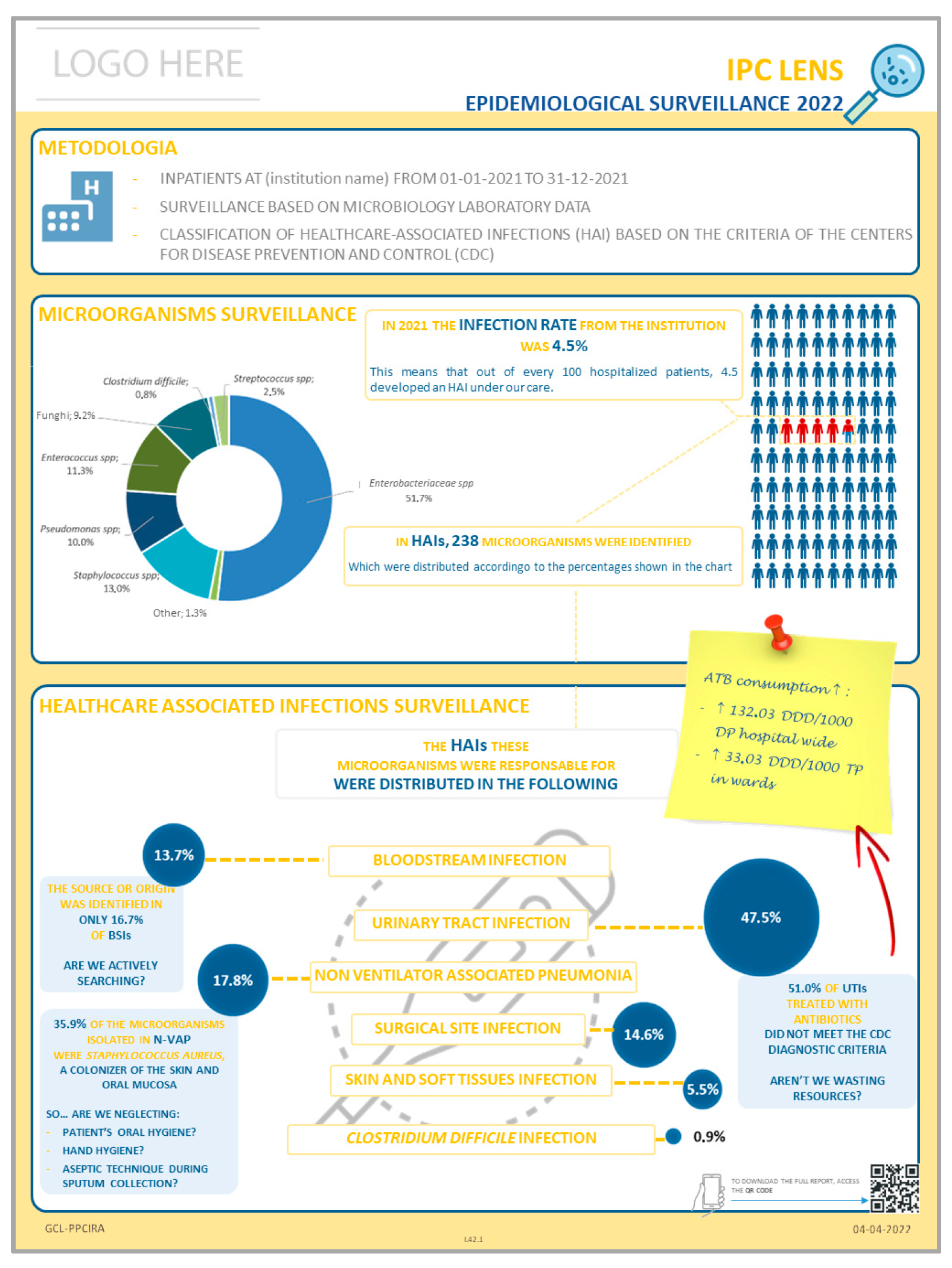

(…) the data on respiratory infections that you put there, ‘Are we neglecting oral hygiene?’ caught my attention (…) and being able to connect everything, it’s definitely an important improvement in my ward.(P8)

It allows us to create improvement projects, within our own wards, by seeing what we’re really not doing so well, and so, focus on the problem and implement actions to correct it.(P10)

3.2. Infographic Use

3.2.1. Accessibility of Information

(…) through the posters (the infographics) people have easy access, they don’t need to go looking anywhere because it’s right there, visible, and if they’re interested … it’s in front of us, we don’t have to do anything, just be interested.(P3)

It’s even more perceptible than actually reading the report, isn’t it? It takes less effort, you look at the diagram and all the information is there in a systematic way. I think that, without a doubt, this might be the main reason why people now give more value, or pay more attention, in this case, to the report data (…) it’s a very innovative way, it’s easily perceptible and visible.(P11)

(…) these latest forms of information, I think they were easier, it was an easier way to reach colleagues. Because it’s something that isn’t hidden and that we don’t have to go looking for. And so people are more likely, even if just to look and see what it is, and they end up reading it and sometimes even getting interested in finding more information. So, I think there was an evolution, really a way to reach team members.(P13)

We live in a time where we no longer have time. We no longer have time for deep reflections, we want to avoid complexity, having more work. Infographics, in a simplified way, really allow us to implement solutions (…) this really speaks to us, it truly appeals to our common sense, honestly, and we immediately get the idea (…) it’s about wanting to improve.(P10)

(…) I didn’t like that it was placed behind the door. I don’t think it’s an appropriate spot.(P8)

It needs to be clearly visible (…) it has to be displayed so that colleagues can notice and see it. The location is very important. It’s not behind a door that we just stick it.(P13)

Then, since it has the QR code, we can download the Institution’s entire report.(P10)

(…) the information has to be delivered in an objective way. It has to be really concise because, considering all the hustle we deal with and the concerns related to the ward, it needs to be something very concise. It has to be there and ready. And if we have any doubts, we can access through the QR code, and that helps a lot.(P13)

3.2.2. Readability and Interpretability

It’s a method that, in my opinion, is more inviting to read.(P1)

We’re able to read it in a summarized and easy way (…) here we have all the information organized, easy to interpret, and then it’s easy to pass it on to others, to our peers.(P2)

It’s something we can do in the meantime, in a little bit of time we may have during worktime, it’s quick to read (the infographic), easy to interpret, it has the most relevant and most important information. I think that’s what makes it easier and makes the message get across.(P7)

3.2.3. Visual Design

It’s simple and clearly laid out with inviting colors.(P1)

The colours, they’re ok, it’s not all one colour. There’s something that stands out, so it helps us filter out some more relevant information. And presenting graphs also helps.(P3)

The colour palette is pleasant (…) It’s visually attractive and so, you can immediately get a summary and everyone sees it.(P10)

(…) even the images in the diagrams end up being appealing. They could just be lines, but no, everything has its purpose and its reason. And I think that is, without a doubt, an added value.(P11)

(…) I think that if we mix too many colours, it also gets a bit confusing. I don’t know… it becomes noisy.(P1)

(…) the simpler, the better.(P5)

The reflections, at the end of the data, the reflections (…) I think sometimes make us think a bit about things (…) It’s essentially that question—What can we do, isn’t it? It’s not just about looking at the data. Are we neglecting something?(P8)

(…) and the reminders on the side, that are placed there (on the infographic) and that make us cross-reference the information to what is the most important.(P10)

3.3. Team Engagement

3.3.1. Motivation

I think that sometimes there isn’t much interest in knowing the data. It’s not that it isn’t provided, because it is, but sometimes I don’t really see much interest.(P3)

(…) the knowledge or lack of knowledge of each professional depends on what we set out to do (…) you can send the reports, you can give access to all kinds of documents, but there has to be interest from the professionals.(P6)

3.3.2. Complementary Strategies for Dissemination

If the infographic is transformed into some kind of information delivered through the mobile phone or an app, specific to the healthcare professional, who can access it in a schematic way like the paper infographic, but in the form of an app.(P11)

(…) to know the general opinion, like using a mini-survey to know what people became aware of, or whether the location chosen was appropriate, if they were aware of it, or not (…) sometimes we might think it’s in the most suitable place, but maybe it’s not.(P1)

(…) at the end of the shift handover, dedicate a little time to the infographic and explain what it is, what is the objective, what are the results (…) even the IPC link nurses should take a more active role in sharing this information.(P3)

Elevate the infographic and explain (…) I would like to have access to the data from the ward, my ward in particular.(P8)

As soon as the results came out, we could do a training session, a short training session. The IPC link nurses should do it.(P4)

Maybe that data could be shared with the rest of the team, maybe the failure also lies a bit with the IPC link nurses not doing it, or at least trying to get those alerts across, right?(P12)

The IPC link nurses need dedicated time to be able to work this data within the wards themselves, and act more effectively and in close connection with the IPC team. And I think that from there, things would be disseminated differently.(P10)

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Awareness

4.2. Infographic Use

4.3. Team Engagement

Infographics as Catalysts for Quality Improvement Initiatives

4.4. Implications for Practice and Research

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-154992-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, B.G.; Russo, P.L. Preventing Healthcare-Associated Infections: The Role of Surveillance. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.M. Reflexos da Tecnologia Digital no Processo de Comunicação da Ciência. In Una Mirada a La Ciencia de La Información desde Los Nuevos Contextos Paradigmáticos de La Posmodernidad; Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências: Marília, Portugal, 2017; pp. 179–196. ISBN 978-85-7983-904-7. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.J.; Turnquist, A.; Groot, B.; Huang, S.Y.M.; Kok, E.; Thoma, B.; Van Merriënboer, J.J.G. Exploring the Role of Infographics for Summarizing Medical Literature. Health Prof. Educ. 2019, 5, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.; Fawkner, S.; Oliver, C.; Murray, A. Why Healthcare Professionals Should Know a Little about Infographics. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1104–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiciklas, M. The Power of Infographics: Using Pictures to Communicate and Connect with Your Audiences; Que Pub: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-7897-4949-9. [Google Scholar]

- Balkac, M.; Ergun, E. Role of Infographics in Healthcare. Chin. Med. J. 2018, 131, 2514–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrorie, A.; Donnelly, C.; McGlade, K. Infographics: Healthcare Communication for the Digital Age. Ulster Med. J. 2016, 85, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siricharoen, W.V.; Siricharoen, N. Infographic Utility in Accelerating Better Health Communication. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2018, 23, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, R. Infographics, Assessment and Digital Literacy: Innovating Learning and Teaching through Developing Ethically Responsible Digital Competencies in Public Health. In Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education 2019; Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education: Tugun, Australia, 2019; pp. 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmarini, E.; Marciano, L.; Schulz, P.J. The Effectiveness of Visual-Based Interventions on Health Literacy in Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Retamero, R.; Cokely, E.T. Designing Visual Aids That Promote Risk Literacy: A Systematic Review of Health Research and Evidence-Based Design Heuristics. Hum. Factors 2017, 59, 582–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butdisuwan, S.; Annamma, L.M.; Subaveerapandiyan, A.; George, B.T.; Kataria, S. Visualising Medical Research: Exploring the Influence of Infographics on Professional Dissemination. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 5422121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Patel, C.; Oreper, J.; Patel, H.; Sajedeen, A. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Infographics Within Medical Information Response Letters. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Muñoz, E.-M.; Valera-Gran, D.; García-Campos, J.; Lozano-Quijada, C.; Hernández-Sánchez, S. Enhancing Evidence-Based Practice Competence and Professional Skills Using Infographics as a Pedagogical Strategy in Health Science Students: Insights from the InfoHealth Project. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kgatla, M.N.; Ramavhoya, T.I.; Rasweswe, M.M.; Mulaudzi, F.M. Using Infographics to Empower Nursing Students on Integrating Ubuntu, HIV/AIDS and TB at a Selected University, South Africa. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Monroy, A.; Rivas-Paterna, A.B.; Orgaz-Rivas, E.; García-González, F.J.; González-Sanavia, M.J.; Moreno, G.; Pacheco, E. Use of Infographics for Facilitating Learning of Pharmacology in the Nursing Degree. Nurs. Open 2022, 10, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, K.; Yaghoubi, A.; Kholousi, S.; Yousofzadeh, M.; Zanganeh, A.; Gharayi, M.; Namazinia, M. Comparative Study on the Impact of ‘Infographic versus Video Feedback’ on Enhancing Students’ Clinical Skills in Basic Life Support. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslin, R.; Alhabsyi, F.; Mashuri, S. Semi-Structured Interview: A Methodological Reflection on the Development of a Qualitative Research Instrument in Educational Studies. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2022, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.R.; Murray, A.D.; Wordie, S.J.; Oliver, C.W.; Murray, A.W.; Simpson, A.H.R.W. Maximising the Impact of Your Work Using Infographics. Bone Jt. Res. 2017, 6, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcia, A.; Suero-Tejeda, N.; Bales, M.E.; Merrill, J.A.; Yoon, S.; Woollen, J.; Bakken, S. Sometimes More Is More: Iterative Participatory Design of Infographics for Engagement of Community Members with Varying Levels of Health Literacy. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2016, 23, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições 70: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; ISBN 978-85-62938-04-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DoH-Oct2013.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Surveillance of Health Care-Associated Infections at National and Facility Levels: Practical Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-010145-6. [Google Scholar]

- Birgand, G.; Johansson, A.; Szilagyi, E.; Lucet, J.-C. Overcoming the Obstacles of Implementing Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gause, G.; Mokgaola, I.O.; Rakhudu, M.A. Technology Usage for Teaching and Learning in Nursing Education: An Integrative Review. Curationis 2022, 45, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control In-Service Education and Training Curriculum; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-009412-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.M. A Primer on How to Create a Visual Abstract. J. Trauma Nurs. 2016. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/journaloftraumanursing/Documents/VisualAbstract_Primerv1.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Sheth, B.R.; Young, R. Two Visual Pathways in Primates Based on Sampling of Space: Exploitation and Exploration of Visual Information. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Sonnenberg, L.; Riis, J.; Barraclough, S.; Levy, D.E. A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, F.; Calzavarini, F.; Bianco, P.; Vecchietti, R.G.; Macor, A.F.; D’Orazio, A.; Dragonetti, A.; D’Alfonso, A.; Belletrutti, L.; Floris, M.; et al. A Nudge Intervention to Improve Hand Hygiene Compliance in the Hospital. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acker, A.; Bowler, L.; Pangrazio, L. Guest Editorial: Special Issue—Perspectives on Data Literacies. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2024, 125, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Vyas, P.; D’Agostino, F.; Wieben, A.; Coviak, C.; Mullen-Fortino, M.; Park, S.; Sileo, M.; Brown, S.; De Souza, E.N.; et al. Data Literacy and Data Science Literacy for Nurses: State of the Art Literature Review. In Innovation in Applied Nursing Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B. A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Claremont, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2009; ACM: Claremont, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, M.J. Infographics and Communicating Complex Information. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Users and Interactions; Marcus, A., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9187, pp. 267–276. ISBN 978-3-319-20897-8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filipe, S.; Borges, M.M.; Castilho, A.; Bastos, C. The Use of Infographics to Inform Infection Prevention and Control Nursing Practice: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222961

Filipe S, Borges MM, Castilho A, Bastos C. The Use of Infographics to Inform Infection Prevention and Control Nursing Practice: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222961

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilipe, Susana, Maria Manuel Borges, Amélia Castilho, and Celeste Bastos. 2025. "The Use of Infographics to Inform Infection Prevention and Control Nursing Practice: A Descriptive Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222961

APA StyleFilipe, S., Borges, M. M., Castilho, A., & Bastos, C. (2025). The Use of Infographics to Inform Infection Prevention and Control Nursing Practice: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(22), 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222961