Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Reluctance to Access Psychological Support and Wellness Resources During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

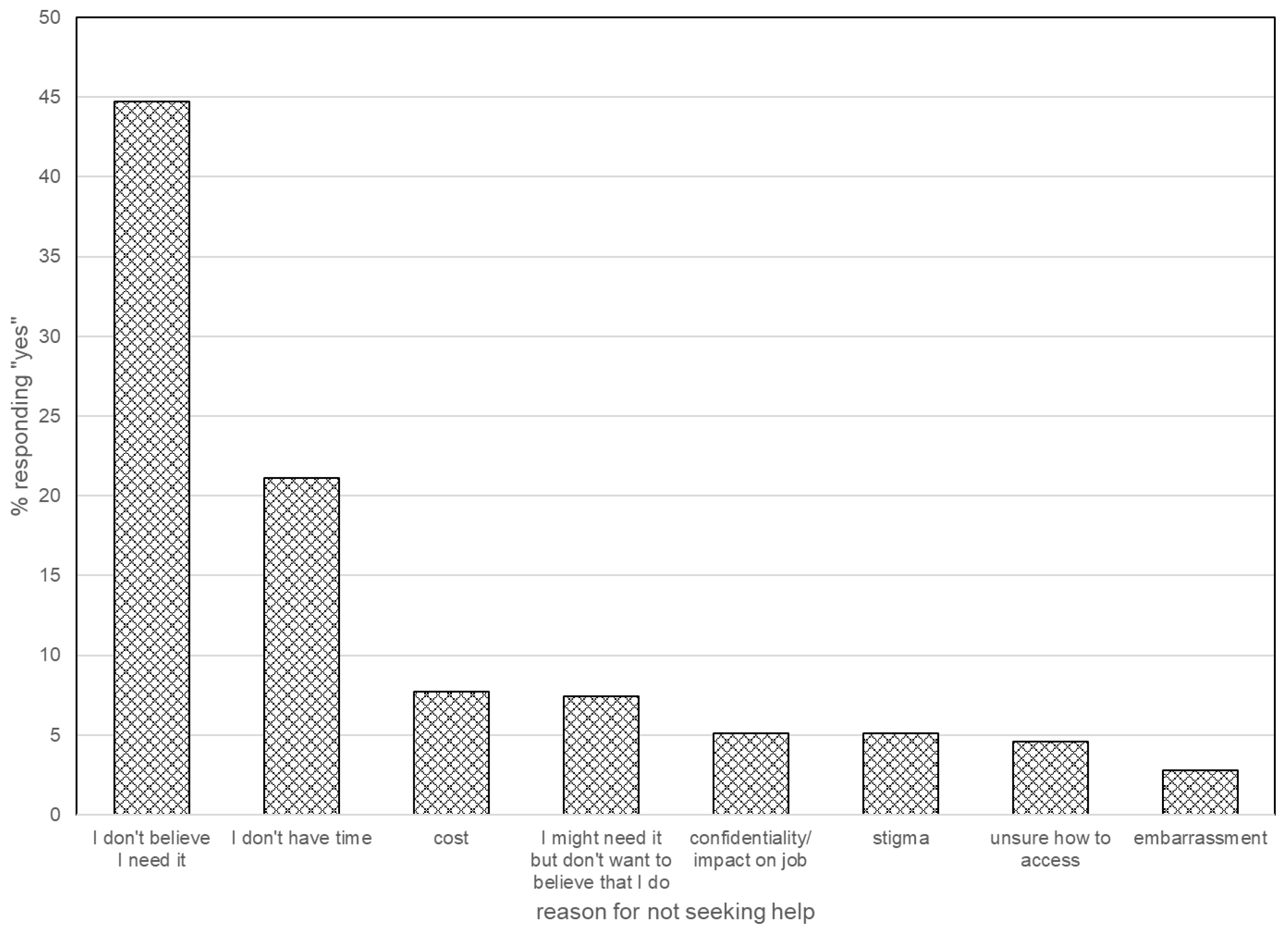

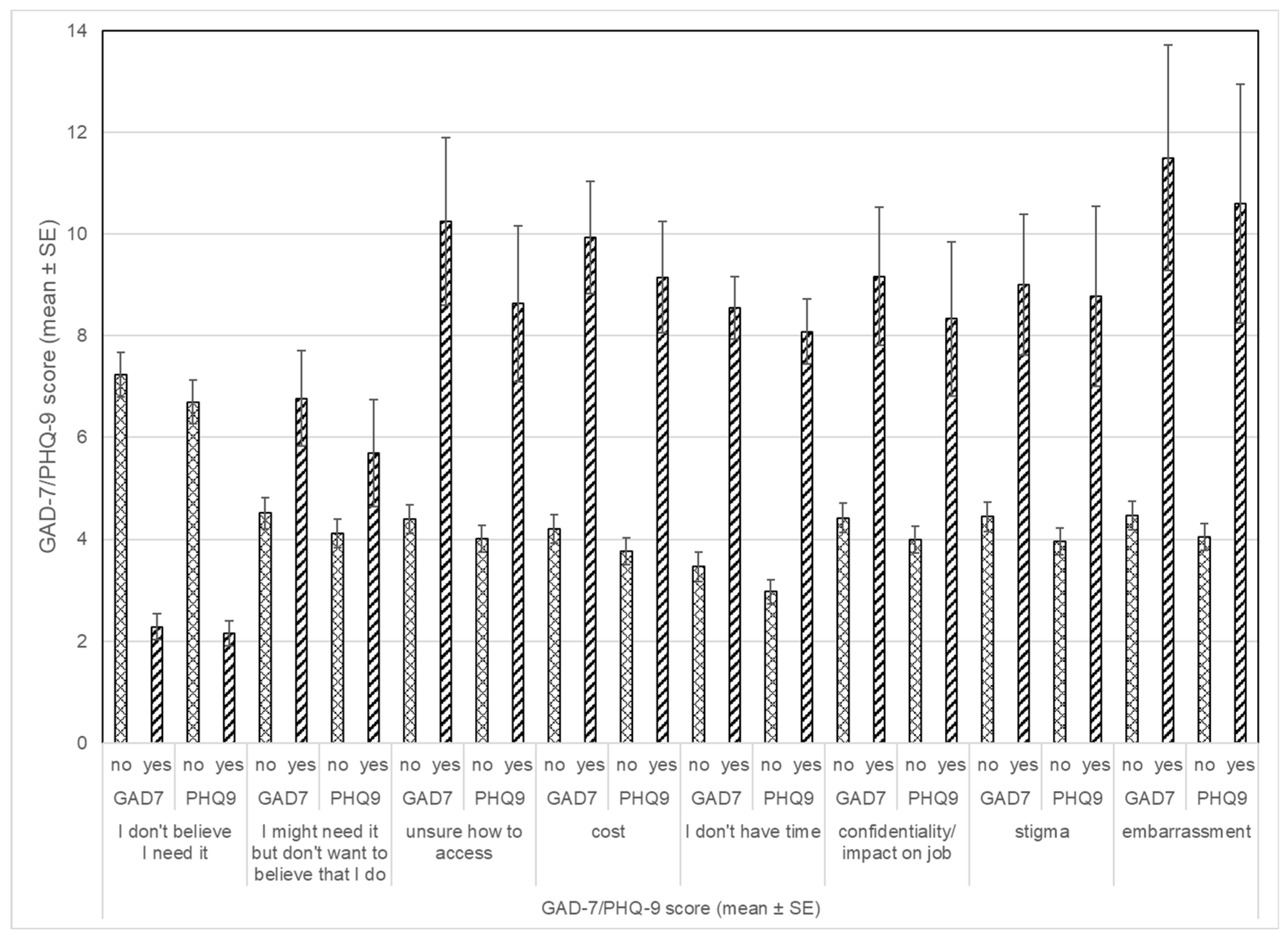

3. Results

3.1. Overall Study Sample

3.2. Findings for Individuals with Signs of Emotional Distress

4. Discussion

4.1. Anxiety and Depression Among ED Staff Compared to Others

4.2. Burnout

4.3. Actively Sought Support

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Emergency Department |

| HCW | Healthcare Workers |

| ACEP | American College of Emergency Physicians |

| PHQ9 | Patient Health Questionnaire—9 Item |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale—7 Item |

References

- Müller, N. Infectious diseases and mental health. In Comorbidity of Mental and Physical Disorders; Sartorius, N., Holt, R.I.G., Maj, M., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Z.; Han, M.F.; Luo, T.D.; Ren, A.K.; Zhou, X.P. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2020, 38, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Ferrand, J.; Fried, J.; Robinson, K. Healthcare workers’ mental health and quality of life during COVID-19: Results from a mid-pandemic, national survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 72, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.; Chew, N.W.; Lee, G.K.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Yeo, L.L.; Zhang, K.; Chin, H.-K.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.E.; Styra, R.; Gold, W.L. Mitigating the psychological effects of COVID-19 on health care workers. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E459–E460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Peng, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chang, J.; Chan, C.-H.; Yang, D.-Y. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.H.; Pacella-LaBarbara, M.L.; Ray, J.M.; Ranney, M.L.; Chang, B.P. Healing the Healer: Protecting Emergency Health Care Workers’ Mental Health During COVID-19. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butun, A. Healthcare staff experiences on the impact of COVID-19 on emergency departments: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 24, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The US Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Noseworthy, J.H. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.; Jacobs, B.; Manfredi, R.A. Moral Injury: The invisible Epidemic in COVID Health Care Workers. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willan, J.; King, A.J.; Jeffery, K.; Bienz, N. Challenges for NHS hospitals during COVID-19 epidemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, E.D.; Mohr, D.; Lempa, M.; Joos, S.; Fihn, S.D.; Nelson, K.M.; Helfrich, C.D. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometric evaluation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; Ferrand, J.; O’sUllivan, D.M.; Robinson, K. Healthcare worker mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19: Mid-Pandemic Survey Results. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 924913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Medical School, 2007. National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Data Table 2: 12-Month Prevalence DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI Disorders by Sex and Cohort. 21 August 2017. Available online: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Kulkarni, A.; Khasne, R.W.; Dhakulkar, B.S.; Mahajan, H.C. Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Results of a Questionnaire-based Survey. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgantini, L.A.; Naha, U.; Wang, H.; Francavilla, S.; Acar, Ö.; Flores, J.M.; Crivellaro, S.; Moreira, D.; Abern, M.; Eklund, M.; et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health among Emergency Physicians. American College of Emergency Physicians. 2020. Available online: www.emergencyphysicians.org/globalassets/emphysicians/all-pdfs/acep20_mental-health-poll-analysis.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Raja, S.; Stein, S.L. Work-life balance: History, costs, and budgeting for balance. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2014, 27, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Single-Item Burnout Measure | Yes | No |

| I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout. | 42 (12%) | 309 (88%) |

| Occasionally I am under stress, and I don’t always have as much energy as I once did, but I don’t feel burned out. | 157 (45%) | 194 (55%) |

| I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion. | 82 (23%) | 269 (77%) |

| The symptoms of burnout that I’m experiencing won’t go away. I think about frustration at work a lot. | 21 (6%) | 330 (94%) |

| I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help. | 8 (2%) | 343 (98%) |

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of Support | Yes | No |

| Family | 248 (71%) | 103 (29%) |

| Friends | 210 (60%) | 141 (40%) |

| Work leadership | 100 (29%) | 251 (72%) |

| Work peers | 175 (50%) | 176 (50%) |

| Specialized work programs | 11 (3%) | 340 (97%) |

| Religious groups | 20 (6%) | 331 (94%) |

| Private therapist/mental health provider | 22 (6%) | 329 (94%) |

| Other | 4 (1%) | 347 (99%) |

| None | 16 (5%) | 335 (95%) |

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Have you actively sought psychological or emotional support during this time? | 38 (13%) | 248 (87%) |

| Type of Support | ||

| Reading articles | 20 (6%) | 331 (94%) |

| Phone call to support system | 10 (3%) | 341 (97%) |

| Attending webinars targeting wellness/emotional health | 8 (2%) | 343 (98%) |

| Video appointments with behavioral health specialist | 18 (5%) | 333 (95%) |

| In-person appointments with behavioral health specialist | 10 (3%) | 341 (97%) |

| Voluntary participation in groups | 3 (0.9%) | 348 (99%) |

| GAD-7 | PHQ-9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping Behaviors | rho | p | n | rho | p | n |

| Time with family | 0.215 | <0.001 | 281 | 0.274 | <0.001 | 283 |

| Time with friends | 0.131 | 0.029 | 279 | 0.200 | 0.001 | 281 |

| Exercise | 0.176 | 0.003 | 278 | 0.273 | <0.001 | 280 |

| TV/Computer | −0.037 | 0.541 | 277 | 0.005 | 0.938 | 279 |

| Dining out | −0.011 | 0.860 | 276 | −0.003 | 0.956 | 278 |

| Bars/Nightlife | −0.026 | 0.667 | 275 | 0.037 | 0.538 | 277 |

| Drinking at home | −0.229 | <0.001 | 275 | −0.187 | 0.002 | 277 |

| Reading | 0.067 | 0.265 | 276 | 0.070 | 0.247 | 278 |

| Sleeping | 0.064 | 0.287 | 276 | 0.057 | 0.342 | 278 |

| Working more | −0.187 | 0.002 | 277 | −0.172 | 0.004 | 279 |

| Working less | −0.055 | 0.368 | 271 | −0.030 | 0.622 | 273 |

| Traveling/Vacation | 0.043 | 0.479 | 274 | 0.118 | 0.051 | 276 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; Ferrand, J.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Robinson, K. Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Reluctance to Access Psychological Support and Wellness Resources During COVID-19. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222887

Young KP, Kolcz DL, Ferrand J, O’Sullivan DM, Robinson K. Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Reluctance to Access Psychological Support and Wellness Resources During COVID-19. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222887

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Kevin P., Diana L. Kolcz, Jennifer Ferrand, David M. O’Sullivan, and Kenneth Robinson. 2025. "Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Reluctance to Access Psychological Support and Wellness Resources During COVID-19" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222887

APA StyleYoung, K. P., Kolcz, D. L., Ferrand, J., O’Sullivan, D. M., & Robinson, K. (2025). Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Reluctance to Access Psychological Support and Wellness Resources During COVID-19. Healthcare, 13(22), 2887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222887