Providing Compassionate Care: A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue Among Midwives and Gynecologists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

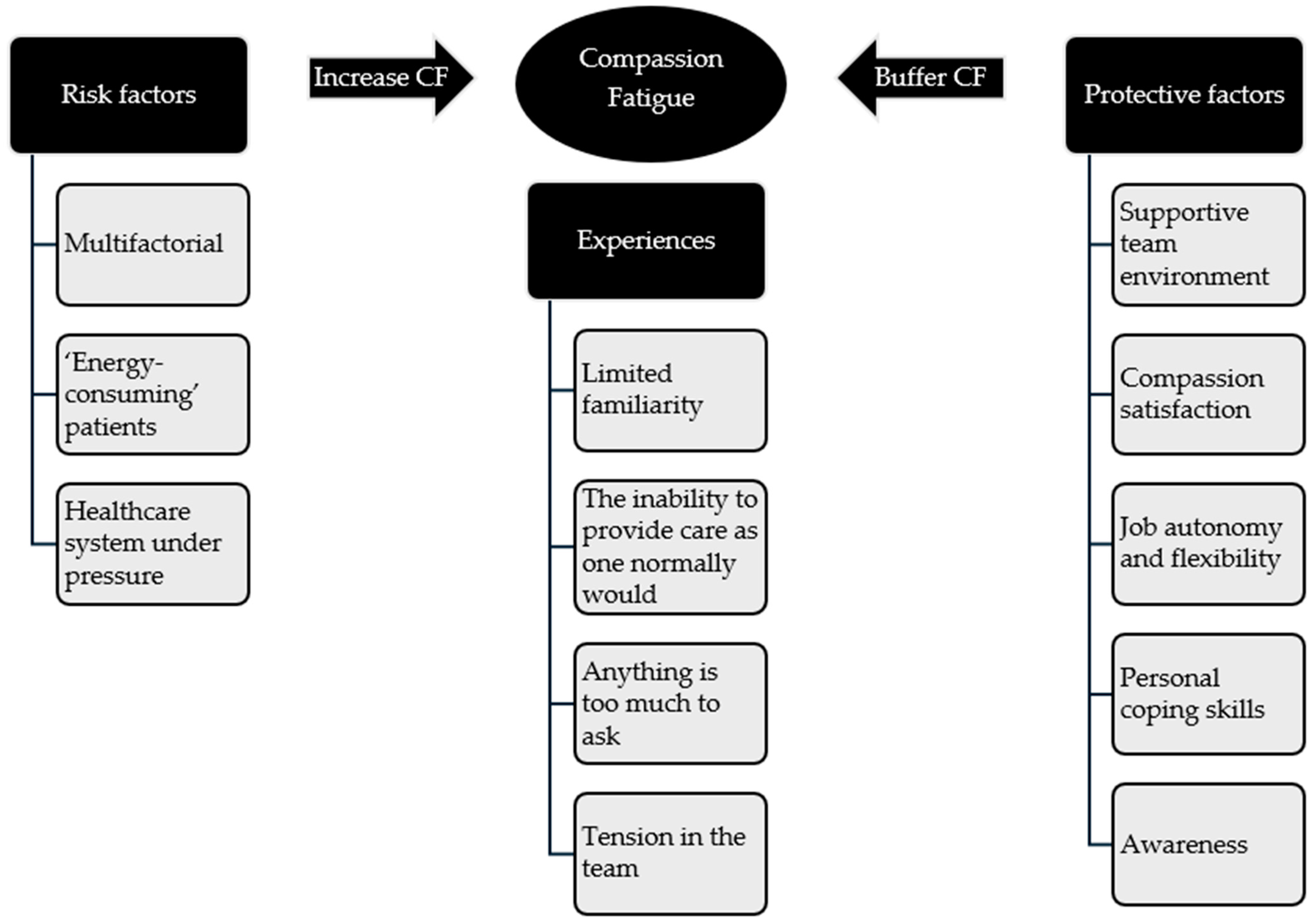

3.2. Experiences

3.2.1. Limited Familiarity

3.2.2. The ‘Inability to Provide Care as One Normally Would’

3.2.3. Anything Is Too Much to Ask

3.2.4. Tension in the Team

3.3. Risk Factors

3.3.1. Multifactorial

3.3.2. ‘Energy-Consuming’ Patients

3.3.3. Healthcare System Under Pressure

3.4. Protective Factors

3.4.1. Supportive Team Environment

3.4.2. Compassion Satisfaction

3.4.3. Job Autonomy and Flexibility

3.4.4. Personal Coping Skills

3.4.5. Awareness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Compassion fatigue |

| CS | Compassion satisfaction |

| STS | Secondary traumatic stress |

| MSc | Master of Science |

References

- Day, J.R.; Anderson, R.A. Compassion fatigue: An application of the concept to informal caregivers of family members with dementia. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 408024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, A.G.; Downing, C.; Temane, A.; Hastings-Tolsma, M. Compassion fatigue in nurses: A metasynthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4364–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, S.K.; Klopper, H.C. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2010, 12, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E. Compassion fatigue in nursing: A concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2018, 53, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Treating Compassion Fatigue; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Venturato, L.; Mijovic-Kondejewski, J.; Smith-MacDonald, L. Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 69, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misouridou, E. Secondary posttraumatic stress and nurses’ emotional responses to patient’s trauma. J. Trauma Nurs. 2017, 24, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinheiser, M. Compassion fatigue among nurses in skilled nursing facilities: Discoveries and challenges of a conceptual model in research. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 44, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabo, B.M. Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2011, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, S.; Chen, H.-C.; Maughan, D.; Heaston, S. Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2015, 47, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E. Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, T.; Shah, H.; Falconieri, N.; Timmerman, D.; Lees, C.; Wright, A.; Lumsden, M.A.; Regan, L.; Van Calster, B. Burnout, well-being and defensive medical practice among obstetricians and gynaecologists in the UK: Cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman-Martos, N.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Vargas-Román, K.; Ramirez-Baena, L.; Ortega-Campos, E.; De La Fuente-Solana, E.I. Prevalence and predictors of burnout in midwives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheen, K.; Spiby, H.; Slade, P. Exposure to traumatic perinatal experiences and posttraumatic stress symptoms in midwives: Prevalence and association with burnout. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsantoni, K.; Zartaloudi, A.; Papageorgiou, D.; Drakopoulou, M.; Misouridou, E. Prevalence of compassion fatigue, burn-out and compassion satisfaction among maternity and gynecology care providers in Greece. Mater. Sociomed. 2019, 31, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.; Watt, F.; Jansen, B.; Coghlan, E.; Nathan, E.A. Minimising compassion fatigue in obstetrics/gynaecology doctors: Exploring an intervention for an occupational hazard. Australas. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirik, D.; Sak, R.; Şahin-Sak, İ.T. Compassion fatigue among obstetricians and gynecologists. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4247–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasse, M.; Schroll, A.M.; Karro, H.; Schei, B.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Van Parys, A.S.; Ryding, E.L.; Tabor, A.; On Behalf of the Bidens Study Group. Prevalence of experienced abuse in healthcare and associated obstetric characteristics in six European countries. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmir, R.; Schmied, V.; Wilkes, L.; Jackson, D. Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: A meta-ethnography. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2142–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Yang, Y.Y.; Ang, E. The impact of negative childbirth experience on future reproductive decisions: A quantitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.; Ayers, S.; Bogaerts, A.; Jeličić, L.; Pawlicka, P.; Van Haeken, S.; Uddin, N.; Xuereb, R.B.; Kolesnikova, N.; COST Action CA18211:DEVoTION Team. When birth is not as expected: A systematic review of the impact of a mismatch between expectations and experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harling, M.N.; Högman, E.; Schad, E. Breaking the taboo: Eight Swedish clinical psychologists’ experiences of compassion fatigue. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2020, 15, 1785610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B.H. Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test. In Treating Compassion Fatigue; Figley, C.R., Ed.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N.; Mattern, E.; Cignacco, E.; Seliger, G.; König-Bachmann, M.; Striebich, S.; Ayerle, G.M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternity staff in 2020—A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cass, I.; Duska, L.R.; Blank, S.V.; Cheng, G.; duPont, N.C.; Frederick, P.J.; Hill, E.K.; Matthews, C.M.; Pua, T.L.; Rath, K.S.; et al. Stress and burnout among gynecologic oncologists: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology evidence-based review and recommendations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, L.; Feijen-de Jong, E.I.; Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Jaarsma, D.A.C. Midwives’ occupational wellbeing and its determinants: A cross-sectional study among newly qualified and experienced Dutch midwives. Midwifery 2023, 125, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibazadeh, E.; Namadian, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Rashidian, A.; Nogueira Pileggi, V.; Madeira, S.; Leathersich, S.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Oladapo, O.T.; et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG 2018, 125, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Early, S.F.; Mahrer, N.E.; Klaristenfeld, J.L.; Gold, J.I. Group cohesion and organizational commitment: Protective factors for nurse residents’ job satisfaction, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction and burnout. J. Prof. Nurs. 2014, 30, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missouridou, E.; Karavasopoulou, A.; Psycharakis, A.; Segredou, E. Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among addiction nursing care providers in Greece: A mixed-method study design. J. Addict. Nurs. 2021, 32, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Singh-Carlson, S.; Odell, A.; Reynolds, G.; Su, Y. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses in the United States and Canada. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43, E161–E169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkman, T.; Dijksman, L.M.; Baas, M.A.M.; Evers, R.; van Pampus, M.G.; Stramrood, C.A.I. Traumatic experiences and the midwifery profession: A cross-sectional study among Dutch midwives. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2019, 64, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. The Fearless Organization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangachari, P.; Woods, J.L. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, T.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.P. The effect of resilience and self-efficacy on nurses’ compassion fatigue: A cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2030–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Number | Midwife (M) or Gynecologist (G) | Area of Practice | Years of Professional Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Hospital setting | 13 |

| 2 | M | Community care | 27 |

| 3 | G 1 | Private practice | 30 |

| 4 | M | Hospital setting | 14 |

| 5 | M | Private practice | 15 |

| 6 | M | Hospital setting | 9 |

| 7 | M | Hospital setting and private practice | 6 |

| 8 | M | Hospital setting | 15 |

| 9 | G | Hospital setting | 8 |

| 10 | G | Hospital setting and private practice | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vandekerkhof, S.; Malisse, L.; Steegen, S.; D’haenens, F.; Kindermans, H.; Van Haeken, S. Providing Compassionate Care: A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue Among Midwives and Gynecologists. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222908

Vandekerkhof S, Malisse L, Steegen S, D’haenens F, Kindermans H, Van Haeken S. Providing Compassionate Care: A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue Among Midwives and Gynecologists. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222908

Chicago/Turabian StyleVandekerkhof, Sarah, Laura Malisse, Stefanie Steegen, Florence D’haenens, Hanne Kindermans, and Sarah Van Haeken. 2025. "Providing Compassionate Care: A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue Among Midwives and Gynecologists" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222908

APA StyleVandekerkhof, S., Malisse, L., Steegen, S., D’haenens, F., Kindermans, H., & Van Haeken, S. (2025). Providing Compassionate Care: A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue Among Midwives and Gynecologists. Healthcare, 13(22), 2908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222908