Do Contemplative Practices Promote Trauma Recovery? A Narrative Review from 2018 to 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contemplative Practices: Theoretical Frameworks

1.2. Trauma and Post-Traumatic Symptoms: Recovery Pathways Through Contemplative Practices

1.3. Aims

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

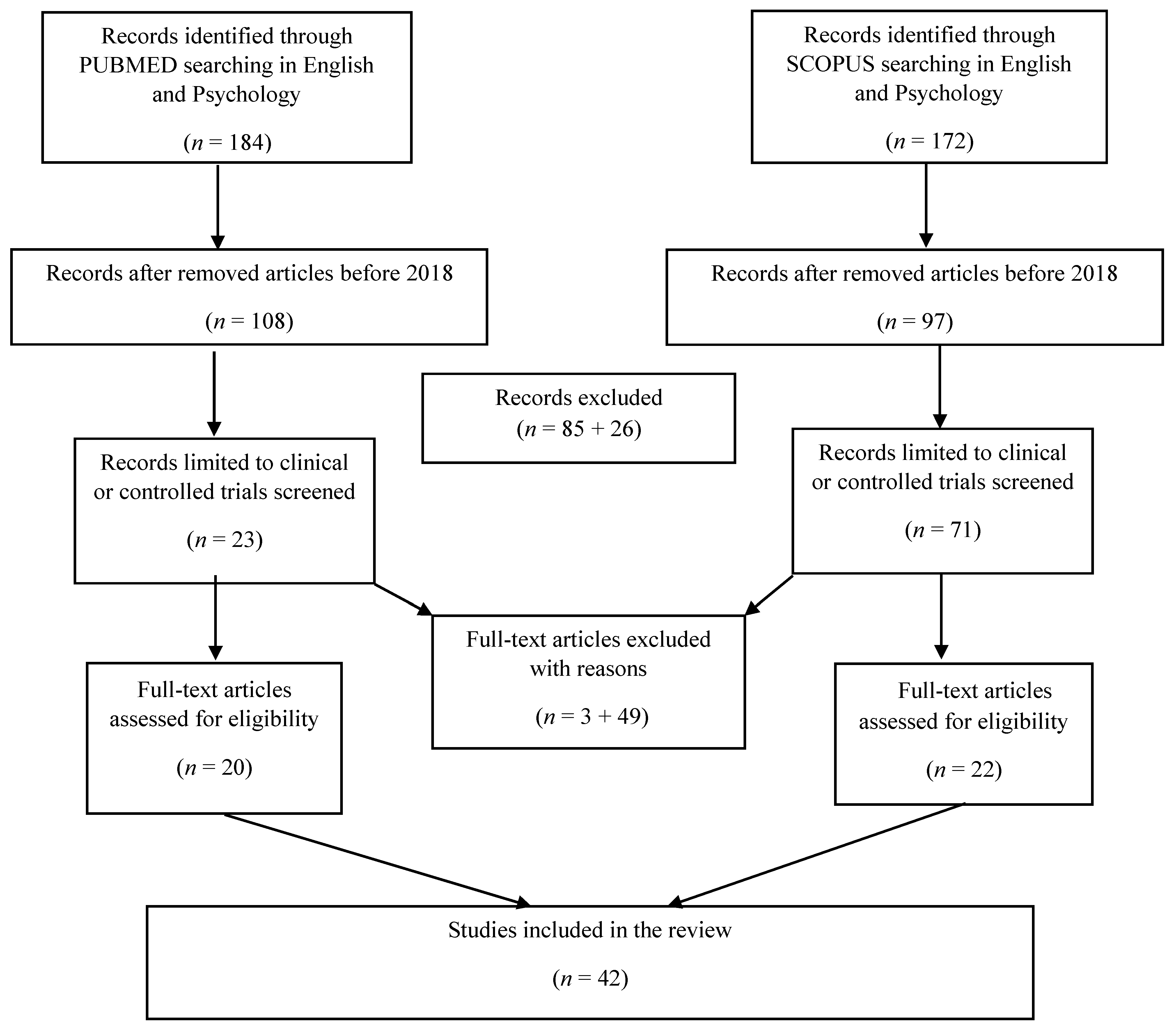

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics: Design and Samples

3.3. Type of Trauma

3.4. Type of Intervention

3.4.1. Contemplative Practices as Single Interventions

3.4.2. Combined Therapeutic Interventions

3.5. Effects of Contemplative Practices on Trauma Recovery

3.6. Measures

3.6.1. Primary Outcome

3.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| General Glossary | |

| AAOc | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-Cancer |

| ANS | Autonomous Nervous System |

| AQoL-8D | Australian Quality of Life (8-dimension) |

| ASI | Addiction Severity Index |

| AUDIT-C | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory-II |

| BEAQ | Brief Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire; |

| BEVS | Bull’s-Eye Values Survey |

| BPM | Brief Problem Monitor |

| BRIEF | Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Function |

| BSI | Brief Symptom Inventory |

| BSI-18 | Brief Symptom Inventory |

| BSSS | Brief Sensation Seeking Scale |

| CAMS-R | Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised |

| CAPS | Clinician-Administered Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Scale |

| CAPS-5 | Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 |

| CARS | Concerns About Recurrence Scale |

| COPE | Coping Orientation to the Problems Experienced |

| CSQ | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| CSQ-8 | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| CTQ-SF | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale |

| DERS | Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale |

| DES | Dissociative Experiences Scale |

| DES’ | Differential Emotions Scale |

| DTS | Davidson Trauma Scale |

| EAC | Emotional Approach Coping scale |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ERQ | Emotion Regulation Questionnaire |

| ERS | Emotion Regulation Scale |

| FCS | fears of compassion scales |

| FFMQ | Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire |

| FMI | Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory |

| FSCRS | Forms of Self-Criticizing/attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale |

| GHQ-28 | General Health Questionnaire |

| HADS-A | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety subscale |

| Ham-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HEBR | Heartbeat-evoked brain response |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| HSCL | Hopkins Symptom Checklist |

| HTQ | The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire |

| IASC | Inventory of Altered Self-Capacities |

| ICG | Impedance Cardiography |

| IES | Impact of Events Scale |

| IES-R | Impact of Events Scale-Revised |

| IIP-32 | Inventory of Interpersonal Problems |

| IMR | Illness Management and Recovery |

| IPDE | International Personality Disorder Examination |

| IPVE | Intimate Partner Violence exposure |

| ISI | Insomnia Severity Index |

| K10 | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale |

| LEC-5 | Life Events Checklist |

| LKM | loving-kindness meditation |

| LKM-S | loving-kindness meditation for self-compassion |

| LSCL-R | Life Stressor Checklist Revised |

| LSI | Leisure Score Index |

| MAAS | Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale |

| MAIA | Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness |

| MBE | Mindful-Breathing Exercise |

| MINI | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NIH PROMIS | National Institutes of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| OAS | Other as Shamer Scale |

| OCSS | Overall Course Satisfaction Survey |

| OLBI | Oldenburg Burnout Inventory |

| PACS | Penn Alcohol Craving Scale |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| PBPT | Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatments |

| PCL-5 | PTSD checklist for DSM-5 |

| PCL-C | PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version |

| PCL-M | PTSD Checklist-Military Version |

| PHLMS | Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PHQ-8 | Patient Health Questionnaire Eight-item version |

| PHQ-9 | Brief Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression |

| PMLD | Postmigration Living Difficulties Scale |

| PROMIS | Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 43-item version |

| PSOM | Positive States of Mind Scales |

| PSQ | Police Stress Questionnaire |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| PSS | PTSD Symptom Scale-Self Report |

| PTSS | The Post-Traumatic Stress Scale |

| PWB | Psychological Well-Being Scale |

| Q-LES-SF | Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire–Short Form |

| RAS | Relationship Assessment Scale |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REDS | Reward-based Eating Drive Scale |

| RMSSD | Root Mean Square of Successive Differences |

| RTSQ | Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire |

| S-Ang | State Anger scale |

| SBC | Scale of Body Connection |

| SCID-I | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV |

| SCL | Skin Conductance Levels |

| SCS | Self-Compassion Scale |

| SCS-R | Social Connectedness Scale–Revised |

| SCS-S | Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form |

| SDQ-20 | Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire |

| SIDES-SR | Structured Interview for Disorders of Extreme Stress, Self-Report version |

| SLESQ | Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire |

| SRET | Self-Referential Encoding Task |

| SRS | Soothing Receptivity Scale |

| SSGS | State Shame and Guilt Scale |

| SSPS | Social Safeness and Pleasure Scale |

| SSS-8 | Eight-item Somatic Symptom Scale |

| SSST | Sing-a-Song Stress Test |

| STAXI-2 | State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory–2 |

| SUD | Subjective Units of Distress Scale |

| TEI | Traumatic Events Inventory |

| TEQ | Toronto Empathy Questionnaire |

| TF | Time Frequency |

| TLFB | Timeline Follow Back |

| TM | Transcendental Meditation |

| TRIER-C | Trier Social Stress Task for Children |

| TSK-11 | Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia |

| UFOV | Useful Field of View Test |

| VAS | Visual Analogue scales |

| VLQ | Valued Living Questionnaire |

| VU-AMS | VU University Monitoring System |

| WAI-SR | Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised |

| WGO-5 | WHO-Five Well-Being Index |

| WHOQOL | World Health Organization Quality of Life, Brief Version |

| WQL-8 | Work Limitations Questionnaire-Short Form |

| WSAS | Work and Social Adjustment Scale |

| Table Glossary | |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| CA-CBT | Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy |

| CBCT | Cognitively-based Compassion Training |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CFT | Compassion Focused Therapy |

| CMT | Compassioned Mind Training |

| HYP | Holistic Yoga Program |

| IIDEA | Intervention for dual problems and early action |

| IE | Integrative exercise |

| IFS | Internal Family System therapy |

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| ITP | Intensive treatment program |

| LKM-S | Listening to the compassion meditation |

| MBCT | Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy |

| MBRP | Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention |

| MBSG | Mind-body skills group |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| MBTR-R | Mindfulness-Compassion Based Trauma Recovery |

| MUSE | Game-based meditation intervention |

| MVA | Motor vehicle accident |

| PCBMT | Primary Care Brief Mindfulness Training |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| TCTSY | Trauma Centered Trauma-Sensitive Yoga |

| TIMBER | Trauma Interventions using Mindfulness-Based Extinction and Reconsolidation |

| TIY | Trauma-informed Yoga |

| TM | Transcendental Meditation |

| TSY | Trauma-sensitive Yoga |

| WLP | Wellness Lifestyle Program |

References

- Bruce, M.M.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Rogers, M.; Anderson, K.M.; Sluys, K.P.; Richmond, T. Trauma Providers’ Knowledge, Views, and Practice of Trauma-Informed Care. J. Trauma Nurs. Off. J. Soc. Trauma Nurses 2018, 25, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Gemignani, A.; Soldani, F. A Systematic Review of a Polyvagal Perspective on Embodied Contemplative Practices as Promoters of Cardiorespiratory Coupling and Traumatic Stress Recovery for PTSD and OCD: Research Methodologies and State of the Art. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparby, T.; Sacchet, M. Defining Meditation: Foundations for an Activity-Based Phenomenological Classification System. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 795077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K. Yoga, Meditation, and Mysticism: Contemplative Universals and Meditative Landmarks; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, W. Search for the Meaning of Life: Essays and Reflections on the Mystical Experience; Liguori/Triumph: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Norbu, N. Il Cristallo e La via Della Luce: Sutra, Tantra e Dzog-Chen; Ubaldini: Rome, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, J. Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory: The Dharma of Natural Systems; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Conversano, C.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Gemignani, A. Mindful-Ness, Age and Gender as Protective Factors Against Psychological Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C.K.; Siegel, R. Wisdom and Compassion in Psychotherapy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Grossman, P.; Hinton, D.E. Loving-Kindness and Compassion Meditation: Potential for Psychological Interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.J.; Strauss, J.L.; Bomyea, J.; Bormann, J.E.; Hickman, S.D.; Good, R.C. The Theoretical and Empirical Basis for Meditation as an Intervention for PTSD. Behav. Modif. 2012, 36, 759–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scafuto, F.; Ghiroldi, S.; Montecucco, N.F.; Presaghi, F. The Mindfulness-Based Gaia Program Reduces Internalizing Problems in High-School Adolescents: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiroldi, S.; Scafuto, F.; Montecucco, N.F. Effectiveness of a School-Based Mindfulness Intervention on Children’s Internalizing and Externalizing Problems: The Gaia Project. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 2589–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafuto, F.; Ghiroldi, S.; Montecucco, N.F.; De Vincenzo, F.; Quinto, R.M.; Presaghi, F. Promoting Well-Being in Early Adolescents through Mindfulness: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzberg, S. Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness. Contemp. Buddhism 2011, 12, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Schneider, S.M.; Kravitz, L.; Mermier, C.; Burge, M. Mind-Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J. Investig. Med. 2013, 61, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G. Optimism, Social Support, and Coping Strategies as Factors Contributing to Posttraumatic Growth: A Meta-Analysis. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietzel, M.T.; Wakefield, J.C. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, A.; Suris, A.; North, C. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, J. Recovery from Psychological Trauma. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1998, 52, S145–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasbi, M.; Sadeghi Bahmani, D.; Karami, G.; Omidbeygi, M.; Peyravi, M.; Panahi, A. Influence of Adjuvant Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) on Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Veterans–Results from a Randomized Control Study. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihai, I.; Kozhevnikov, M. Arousal vs. Relaxation: A Comparison of the Neurophysiological and Cognitive Correlates of Vajrayana and Theravada Meditative Practices. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A.; Stone, L.; West, J.; Rhodes, A.; Emerson, D.; Suvak, M. Yoga as an Adjunctive Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, e559–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.A.; Grant, J.; Daneault, V.; Scavone, G.; Breton, E.; Roffe-Vidal, S.; Courtemanche, J.; Lavarenne, A.S. Impact of Mindfulness on the Neural Responses to Emotional Pictures in Experienced and Beginner Meditators. NeuroImage 2011, 57, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, J. Meditation Research, Past, Present, and Future: Perspectives from the Nalanda Contemplative Science Tradition. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1307, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, U.A.; Evans, D.D.; Baker, H. Determining Psychoneuroimmunologic Markers of Yoga as an Intervention for Persons Diagnosed With PTSD: A Systematic Review. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2018, 20, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, K.E.; Park, C. How Does Yoga Reduce Stress? A Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Change and Guide to Future Inquiry. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzl, L.; Crane-Godreau, M.A.; Payne, P. Movement-Based Embodied Contemplative Practices: Definitions and Paradigms. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S. Interoception and Emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarelli, A.; Scafuto, F.; Crescentini, C.; Matiz, A.; Orrù, G.; Ciacchini, R.; Alfì, G.; Gemignani, A.; Conversano, C. Interoceptive Ability and Emotion Regulation in Mind–Body Interventions: An Integrative Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.W.; Bush, G.; Gollub, R.L.; Fricchione, G.L.; Khalsa, G. Functional Brain Mapping of the Relaxation Response and Meditation. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 1581–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation; Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shannahoff-Khalsa, D. Kundalini Yoga Meditation Techniques in the Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive and OC Spectrum Disorders; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loizzo, J.J. The Subtle Body: An Interoceptive Map of Central Nervous System Function and Meditative Mind-Brain-Body Integration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1373, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S. The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic Substrates of a Social Nervous System. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2001, 42, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopson, D.P.; Hopson, D. The Power of Soul: Pathways to Psychological and Spiritual Growth for African Americans; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, E.; Firehammer, J. Liberation Psychology as the Path Toward Healing Cul-Tural Soul Wounds. J. Couns. Dev. 2008, 86, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVallie, C. Promoting Indigenous Cultural Responsivity in Addiction Treatment Work: The Call for Neurodecolonization Policy and Practice. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2023, 22, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoach, C.D.; Petersen, M. African Spiritual Methods of Healing: The Use of Candomblé in Traumatic Response. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2010, 3, 40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N.M.; Wall, D. African Dance as Healing Modality throughout the Diaspora: The Use of Ritual and Movement to Work through Trauma. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2011, 4, 234–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.J.; Casmar, P.; Hurst, S.; Harrison, T.; Golshan, S.; Good, R. Compassion Meditation for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A Nonrandomized Study. Mindfulness 2017, 11, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Riordan, K.M.; Sun, S.; Davidson, R. The Empirical Status of Mindfulness-Based Interventions: A Systematic Review of 44 Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, J.R.; Fisher, N.E.; Cooper, D.J.; Rosen, R.K.; Britton, W. The Varieties of Contemplative Experience: A Mixed-Methods Study of Meditation-Related Challenges in Western Buddhists. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhi, B. The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Aṅguttara Nikāya; Pāli Text Society in association with Wisdom Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, L.G.; Cann, A.; Tedeschi, R.G. A Correlational Test of the Relationship Be-Tween Posttraumatic Growth, Religion, and Cognitive Processing. J. Trauma. Stress 2000, 13, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.E.; Lanius, R.A.; McKinnon, M. Mindfulness-Based Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of the Treatment Literature and Neurobiological Evidence. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018, 43, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L.A.; Mehling, W.E.; Metzler, T.J.; Cohen, B.E.; Barnes, D.E.; Choucroun, G.J.; Silver, A.; Talbot, L.S.; Maguen, S.; Hlavin, J.A.; et al. Veterans Group Exercise: A Randomized Pilot Trial of an Integrative Exercise Program for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, S.M.; Sheerin, C.M.; Meyer, B. Yoga for Warriors: An Intervention for Veterans with Comorbid Chronic Pain and PTSD. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupe, D.W.; McGehee, C.; Smith, C.; Francis, A.D.; Mumford, J.A.; Davidson, R. Mindfulness Training Reduces PTSD Symptoms and Improves Stress-Related Health Outcomes in Police Officers. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2021, 36, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, L.; Coulange, M.; Reynier, J.C.; Le Quiniat, F.; Molle, A.; Bénéton, F. Comparing Meditative Scuba Diving versus Multisport Activities to Improve Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Pilot, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2022, 13, 2031590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.J.; Malaktaris, A.L.; Casmar, P.; Baca, S.A.; Golshan, S.; Harrison, T. Compassion Meditation for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans: A Randomized Proof of Concept Study. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Lian, Y.; Ma, N. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Influence of Yoga for Women with Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somohano, V.C.; Kaplan, J.; Newman, A.G.; O’Neil, M. Formal Mindfulness Practice Predicts Reductions in PTSD Symptom Severity Following a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Women with Co-Occurring PTSD and Substance Use Disorder. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2022, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Engelmann, M.; Schreiber, C.; Kümmerle, S.; Heidenreich, T.; Stangier, U. A Trauma-Adapted Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness Intervention for Patients with PTSD after Interpersonal Violence: A Multiple-Baseline Study. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1105–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, J.K.; Gordon, J.S.; Hamilton, M. Mind-Body Skills Groups for Treatment of War-Traumatized Veterans: A Randomized Controlled Study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizik-Reebs, A.; Amir, I.; Yuval, K.; Hadash, Y. Candidate Mechanisms of Action of Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees (MBTR-R): Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 90, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren-Schwartz, R.; Aizik-Reebs, A.; Yuval, K.; Hadash, Y. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees on Shame and Guilt in Trauma Recovery among African Asylum-Seekers. Emotion 2023, 23, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.S.; Sponheim, S.R.; Lim, K.O. Interoception underlies therapeutic effects of mindfulness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2022, 7, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, J.N.; Judd, C.M.; Genung, S.; Stanton, A.L.; Arch, J. Intervention and Mediation Ef-Fects of Target Processes in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxious Cancer Survivors in Community Oncology Clinics. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 153, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehling, W.E.; Chesney, M.A.; Metzler, T.J.; Goldstein, L.A.; Maguen, S.; Geronimo, C.; Agcaoili, G.; Barnes, D.E.; Hlavin, J.A.; Neylan, T. A 12-Week Integrative Exercise Program Improves Self-Reported Mindfulness and Interoceptive Awareness in War Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, A.; Lathan, E.C.; Dixon, H.D.; Mekawi, Y.; Hinrichs, R.; Carter, S.; Kaslow, N. Primary Care-Based Mindfulness Intervention for PTSD and Depression Symptoms among Black Adults: A Pilot Feasibility and Acceptability Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 15, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, T.K.; Wen, C.C.; Neelon, B. Predictors of Treatment Completion among Women Receiving Integrated Treatment for Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress and Substance Use Disorders. Subst. Use Misuse 2023, 58, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somohano, V.C.; Bowen, S. Trauma-Integrated Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Women with Comorbid Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use Disorder: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Feasibility and Acceptability Trial. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2022, 28, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possemato, K.; Bergen-Cico, D.; Buckheit, K.; Ramon, A.; McKenzie, S.; Smith, A.R.; Pigeon, W. Randomized Clinical Trial of Brief Primary Care–Based Mindfulness Training versus a Psychoeducational Group for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 84, 44829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classen, C.C.; Hughes, L.; Clark, C.; Hill Mohammed, B.; Woods, P.; Beckett, B. A Pilot RCT of a Body-Oriented Group Therapy For Complex Trauma Survivors: An Adaptation of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. J. Trauma Dissociation 2020, 22, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, A.M.; Heffner, K.L.; Cerulli, C.; Luck, P.; McGuinness, S.; Pigeon, W. Effects of Mindfulness Training on Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms from a Community-Based Pilot Clinical Trial among Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Feng, V.N.; Hodgdon, H.; Emerson, D.; Silverberg, R.; Clark, C. Moderators of Treatment Efficacy in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Trauma-Sensitive Yoga as an Adjunctive Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.W.; Schmid, A.A.; Daggy, J.K.; Yang, Z.; O’Connor, C.E.; Schalk, N. Symptoms Improve after a Yoga Program Designed for PTSD in a Randomized Controlled Trial with Veterans and Civilians. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, L.R.; Falgas-Bague, I.; Ramos, Z.; Porche, M.V. Development of a Cogni-Tive Behavioral Therapy with Integrated Mindfulness for Latinx Immigrants with Co-Occurring Disorders: Analysis of Intermediary Outcomes. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.E.; Hough, C.L.; Jones, D.M.; Ungar, A.; Reagan, W.; Key, M.D.; Porter, L. Effects of Mindfulness Training Programmes Delivered by a Self-Directed Mobile App and by Telephone Compared with an Education Programme for Survivors of Critical Illness: A Pilot Randomised Clinical Trial. Thorax 2019, 74, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Moran, M.; Shomaker, L.B.; Seiter, N.; Sanchez, N.; Verros, M.; Rayburn, S.; Johnson, S.; Lucas-Thompson, R. Health effects of COVID-19 for vulnerable adolescents in a randomized controlled trial. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, B.; Mitrev, L.; Moaddell, R.; Wainer, I. D-Serine Is a Potential Biomarker for Clinical Response in Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Using (R, S)-Ketamine Infusion and TIMBER Psychotherapy: A Pilot Study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2018, 1866, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, M.; Hampton, S.; Brown, K.; Fisher, G.; Steindl, S.R.; Kidd, C.; Kirby, J. Compassionate Mind Training for Ex-Service Personnel with PTSD and Their Partners. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2023, 30, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.J.; Lorenzon, H. Transcendental Meditation for Women Affected by Domestic Violence: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Fam. Violence 2023, 39, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, Z.; Prior, K.N.; Sloan, T.L.; Bond, M.J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Self-Compassion versus Cognitive Therapy for Complex Psychopathologies. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehsen, M.; Stoycheva, V.; Cohen, B.H. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Transcendental Meditation as Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, S.; Williams, H.; Karl, A. Psychophysiological Responses to a Brief Self-Compassion Exer-Cise in Armed Forces Veterans. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 780319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knabb, J.J.; Vazquez, V.E.; Pate, R.A.; Lowell, J.R.; Wang, K.T.; De Leeuw, T.G.; Dominguez, A.F.; Duvall, K.S.; Esperante, J.; Gonzalez, Y.A.; et al. Lectio Divina for Trauma Symptoms: A Two-Part Study. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 2022, 9, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgdon, H.B.; Anderson, F.G.; Southwell, E.; Hrubec, W. Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among Survivors of Multiple Childhood Trauma: A Pilot Effectiveness Study. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2022, 31, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbitts, D.C.; Aicher, S.A.; Sugg, J.; Handloser, K.; Eisman, L.; Booth, L.D.; Bradley, R. Program Evaluation of Trauma-Informed Yoga for Vulnerable Populations. Eval. Program Plan. 2021, 88, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kananian, S.; Soltani, Y.; Hinton, D. Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Plus Problem Management (CA-CBT+) With Afghan Refugees: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Trauma. Stress 2020, 33, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, A.A.T.; Nijhof, K.S.; Scholte, R.; Popma, A. Effectiveness of Game-Based Meditation Therapy on Neurobiological Stress Systems in Adolescents with Posttraumatic Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Stress 2021, 24, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalta, A.K.; Pinkerton, L.M.; Valdespino-Hayden, Z.; Smith, D.L.; Burgess, H.J.; Held, P.; Boley, R.A.; Karnik, N.S.; Pollack, M. Examining Insomnia During Intensive Treatment for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Does It Improve and Does It Predict Treatment Outcomes? J. Trauma. Stress 2020, 33, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandy, C.L.; Dillbeck, M.C.; Sezibera, V.; Taljaard, L.; Wilks, M.; Shapiro, D.; de Reuck, J. Reduction of PTSD in South African University Students Using Transcendental Meditation Practice. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccari, B.; Callahan, M.L.; Storzbach, D.; McFarlane, N.; Hudson, R.; Loftis, J. Yoga for Veterans with PTSD: Cognitive Functioning, Mental Health, and Salivary Cortisol. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, I.; Cashwell, C.S.; Downs, H. Trauma-Sensitive Yoga: A Collective Case Study of Women’s Trauma Recovery from Intimate Partner Violence. Couns. Outcome Res. Eval. 2019, 10, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, K.M.; Noggle Taylor, J.J.; Johnston, J.; Zameer, A.; Cheema, S.; Khalsa, S.B. Kripalu Yoga for Military Veterans With PTSD: A Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbert, T.; Schauer, M.; Neuner, F.; Catani, C. Treating Traumatized Offenders and Veterans by Means of Narrative Exposure Therapy. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robjant, K.; Fazel, M. The Emerging Evidence for Narrative Exposure Therapy in the Treatment of Trauma-Related Mental Illness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiser-Stedman, R.; Smith, P.; McKinnon, A.; Dixon, C.; Trickey, D.; Ehlers, A.; Clark, D.M.; Boyle, A.; Watson, P.; Goodyer, I.; et al. Cognitive therapy as an early treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 58, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, D.; Ventevogel, P.; Rees, S. The Contemporary Refugee Crisis: An Overview of Mental Health an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tol, W.A.; Patel, V.; Tomlinson, M.; Baingana, F.; Galappatti, A.; Panter-Brick, C.; Rahman, A. Scaling up Mental Health Interventions in Low-Resource Settings: A Review of Problem Management Plus (PM+) and Self Help Plus (SH+). Glob. Ment. Health 2020, 7, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe-Johnson, M.K.; Browning, B. Effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Trauma-Related Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2024, 17, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, G.E.; Sanchez, M.; Villalba, K. Acting with Awareness Moderates the Association between Lifetime Exposure to Interpersonal Traumatic Events and Craving via Trauma Symptoms: A Moderated Indirect Effects Model. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, M.; Sparby, T.; Vörös, S.; Jones, R.; Marchant, N. Unpleasant Meditation-Related Experiences in Regular Meditators: Prevalence, Predictors and Conceptual Considerations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, E. Development of a Self-Report Measure of Soothing Receptivity; York University: North York, ON, Canada, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría, M. Effectiveness of a Disability Preventive Intervention for Minority Elders: Six- and Twelve-Month Follow-Up. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, B.V.; Schnurr, P.P.; Mayo, L.; Young-Xu, Y.; Weeks, W.B.; Friedman, M.J. Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e541–e550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges; Constable & Robinson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine, T.P. Vagal Tone, Development, and Depressive Symptoms in Middle Childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Lane, R.D. A Model of Neurovisceral Integration in Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 61, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishith, P.; Resick, P.A.; Griffin, M.G. Pattern of Change in Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive–Processing Therapy for PTSD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A. Annotation: The Role of Prefrontal Deficits, Low Autonomic Arousal, and Early Health Factors in the Development of Antisocial and Aggressive Behavior in Children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blascovich, J. Challenge and Threat Appraisal. In Handbook of Approach and Avoidance Motivation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DeRosa, R.; Pelcovitz, D. Group Treatment for Chronically Traumatized Adolescents: Igniting SPARCS of Change. In Treating Traumatized Children: Risk, Resilience and Recovery; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, T.; Clary, L.K.; Sibinga, E.; Tandon, D.; Musci, R.; Mmari, K. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Trauma-Informed School Prevention Program for Urban Youth: Rationale, Design, and Methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2020, 90, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.B. Promoting Empathy and Reducing Hopelessness Using Contemplative Practices. Teach. Sociol. 2022, 50, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.; Chappell Deckert, J. Contemplative Practices for Self-Care in the Social Work Classroom. Soc. Work 2020, 65, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, E.; Martin, S. Building Nurses’ Resilience to Trauma Through Contempla-Tive Practices. Creat. Nurs. 2020, 26, e90–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A.; Jakobsen, J. Mindfulness: Top–down or Bottom–up Emotion Regulation Strategy? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durà-Vilà, G.; Littlewood, R. Integration of Sexual Trauma in a Religious Narrative: Transformation, Resolution and Growth among Contemplative Nuns. Transcult. Psychiatry 2013, 50, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, S.J. Contemplative Practice, Acceptance, and Healing in Moral Injury. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2022, 28, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Geschwind, N.; Peeters, F. Mindfulness Training Promotes Upward Spirals of Positive Affect and Cognition: Multilevel and Autoregressive Latent Trajectory Modeling Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Vago, D.R.; Barnhofer, T. Introduction to the Special Issue on Mindfulness. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, M.; De Gracia, M.; Rodríguez, R.C.; Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Sánchez-García, Ò.; Demarzo, M.M.P.; Trujols, J.; Carmona, C.; Baños, R.M.; Farré, M. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Substance and Behavioral Addictions: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Bash, H.; Papa, A. Shame and PTSD symptoms. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2014, 6, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, D.; Hopper, E. Mindfulness-Oriented Interventions for Trauma: Integrating Contemplative Practices; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, R.; Lee, D. The Role of Shame and Self-critical Thinking in the Development and Maintenance of Current Threat in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, C.; Lever Taylor, B.; Gu, J.; Kuyken, W.; Baer, R.; Jones, F.; Cavanagh, K. What Is Compassion and How Can We Measure It? A Review of Definitions and Measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 47, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.S.; Sweezy, M.; Schwartz, R. Internal Family Systems Skills Training Manual: Trauma-Informed Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, PTSD & Substance Abuse; PESI Publishing & Media: Eau Claire, WI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany, E.S.; Watson, S.B. Guilt: Elaboration of a Multidimensional Model. Psychol. Rec. 2003, 53, 51–90. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, M.R. Revisiting Shame and Guilt Cultures: A Forty-Year Pilgrimage. Ethos J. Soc. Psychol. Anthropol. 1990, 18, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, W. Mindfulness affected post-traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic growth: Adaptive and maladaptive sides through trauma-related shame and guilt. PsyCh J. 2025, 14, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Authors | Type of Trauma | Type of Contemplative Practices | Duration | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jasbi et al., 2018 [21] | PTSD | MBCT + Citalopram | 8 weekly sessions (60–70 min each) | ↓ PCL-5 (re-experiencing events, avoidance, negative mood and cognition, hyperarousal); ↓ DASS (depression, anxiety, stress). |

| 2 | Goldstein et al., 2018 [47] | PTSD | IE | 36 sessions in 12 weeks (1 h each) | ↓ CAPS-5 total 31 point reduction at post-test; ↓ Subscale of hyperarousal; ↑ LSI (more physical activity); ↑ WHOQOL-BREF greater improvement in the psychological domain but a smaller improvement in the physical domain. Greater number of sessions attended was associated with an improvement in physical quality of life and psychological quality of life. High levels of satisfaction. |

| 3 | Chopin et al., 2020 [48] | PTSD with comorbid chronic pain | Hatha yoga | 10 cohorts (2 to 8 weeks): 90 min each | ↓ PTSD symptoms, kinesiophobia, depression, and anxiety. Follow-up results: ↔ Intrusion and avoidance symptoms; ↑ Social role functioning PROMIS. |

| 4 | Grupe et al., 2021 [49] | Occupational stress | MBSR | 8 weekly sessions | ↓ PSQ operational stress and moderated by gender and years of police experience: younger men showed greater decline in stress also at follow-up; ↓ PCL at post-test and at 5-month follow-up; ↓ Exhaustion subscale of OLBI; ↓ PROMIS anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms; ↓ PANAS negative affect; ↔ PROMIS subscales of pain interference; pain intensity, or physical functioning; ↔ Disengagement subscale of OLBI; ↔ PANAS positive affect; ↔ Physical parameters; ↑ Sleep quality PSQI; ↑ PWB. |

| 5 | Gibert et al., 2022 [50] | PTSD | Scuba diving with mindfulness exercises (the Bathysmed protocol) | 6 days with 10 dives | ↔ PCL-5 at post-test; ↓ Subscale intrusion symptoms (PCL-5) at post-test and 1-month follow-up; ↑ Mindfulness (FMI) at post-test; Large effect size Cohen’s d at 1-month follow-up; ↔ PCL-5 and FMI at 3-month follow-up. |

| 6 | Lang et al., 2019 [51] | PTSD | CBCT | 10 weekly sessions (1 h for each) | ↑ Social connectedness (SCS-R); ↓ PCL-5, PHQ-9, CAPS-5 (subscale hyperarousal), large effect size in hyperarousal, reexperiencing, negative alterations in cognitions. Medium effect size in empathy, mindful awareness, anxiety, rumination. Large effect size in depression. ↔ Differential Emotion Scale (DES): Positive and negative emotions; ↔ Alcohol consumption and all the other variables. |

| 7 | Yi. et al., 2022 [52] | PTSD from MVA | Kripalu yoga | 6 sessions (45 min for each) for 12 weeks | ↓ IES-R at post-test; ↓ Subscales intrusion and avoidance; ↔ Subscale hyperarousal; ↔ IES-R at 3-month follow-up; ↓ DASS-21 at post-test and 3-month follow-up and total score ˂ control; ↓ Subscales depression and anxiety; ↔ Subscale stress. |

| 8 | Somohano et al., 2022 [53] | PTSD-SUD | MBRP | 8 sessions (1 h each) in a 4-week period | Higher duration (i.e., minutes per practice) of formal mindfulness practice → lower PTSD Symptoms (avoidance, arousal, reactivity, negative cognitions and mood in PCL-5) at 6-month follow-up; ↔ Informal practice did not predict any outcomes; ↔ Formal and informal practice did not predict reduction in intrusion symptoms (PCL-5) and craving at 6-month follow-up. |

| 9 | Müller-Engelmann et al., 2019 [54] | Interpersonal violence Childhood sexual or physical abuse Physical violence in adulthood | Trauma-adapted intervention from loving-kindness meditation and MBSR | 8 individual sessions (1.30 h each) | ↓ CAPS-5 at follow-up (especially on avoidance) (9 out of 12 did not meet PTSD criteria); ↓ DTS at post-test and follow-up; ↓ BDI-II at follow-up; ↓ Self-criticism at follow-up; ↔ BSI medium effect sizes; ↑ Mindfulness skills of nonjudging and acting with awareness; ↑ Attention to breath in MBE at follow-up; ↑ Self-compassion at follow-up; ↑ WHO-5 (75%): half of them at post-test. |

| 10 | Staples et al., 2022 [55] | PTSD | MBSG | 10 weeks | ↓ Hyperarousal and avoidance; ↓ PTSD symptoms; ↓ Anger and sleep disturbance; ↔ Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic growth, and health-related quality of life. |

| 11 | Aizik-Reebs et al., 2022 [56] | Traumatized and chronically stressed Forced displacement | MBTR-R | 9 weekly sessions (2.5 h each) | ↓ Post-test change in self-criticism (endorsement and drift rate); ↔ Post-test change in drift rates to self-compassion stimuli; ↑ Post-test increase in self-compassion (endorsement); Type of treatment (MBTR-R; Waitlist) → change of self-criticism (at post-test); → PTSD symptoms (HTQ) and depression (PHQ-9); Type of treatment (MBTR-R; Waitlist) → change of self-compassion (at post-test); → PTSD symptoms (HTQ), but not depression (PHQ-9), |

| 12 | Oren-Schwartz, 2023 [57] | Forced displacement | MBTR-R | 9 weekly sessions (2.5 h each) | MBTR-R, relative to waitlist control → shame (no guilt) at post-test → PTSD symptom severity (HTQ subscale)/depression (PHQ-9) at post-test. |

| 13 | Kang, Sponheim & Lim, 2022 [58] | PTSD from combat | MBSR | 8 weekly sessions | ↓ PCL-5; ↑ Spontaneous alpha power (8–13 Hz) in the posterior electrode cluster but ↔ in the follow-up analysis; ↑ Task-related frontal theta power (4–7 Hz in 140–220 ms after stimulus); ↑ Frontal theta heartbeat-evoked brain responses (HEBR) (3–5 Hz and 265–336 ms after R peak); ↓ CAPS; ↓ PHQ; Type of treatment (MBSR, control) → frontal theta heartbeat evoked brain responses → PCL-5. |

| 14 | Fishbein et al., 2022 [59] | Cancer survivors | ACT | 10 sessions | ↓ Bull’s eye values BEVS (improvement); ↔ VLQ; ACT → SCS, EAC → IES-R; ACT → SCS, EAC, BEVS → CARS and general anxiety HADS-A (marginal mediation); ↑ SCS; ↑ EAC. |

| 15 | Mehling et al., 2018 [60] | PTSD | IE | 36 sessions in 12 weeks (50 min each) | ↓ CAPS-5 (average reduction of 31 points); ↑ FFMQ non-reactivity, pbserving; ↑ MAIA emotional awareness, self-regulation, body listening; ↑ PSOM total, focused attention, restful repose; PSOM and FFMQ non-reactivity → CAPS hyperarousal subscale/psychological WHOQOL (partial mediation). |

| 16 | Powers et al., 2022 [61] | PTSD and chronic trauma exposure to multiple events | Trauma-adapted MBCT group Combined interventions | 8 weekly sessions (1.5 h each) | Good feasibility (75% completers) Good acceptability: high levels of satisfaction (CSQ-8) and several perceived benefits regarding physical state, emotional state, and interpersonal relationships; the most frequently reported barriers (PBPT): participation restrictions, stigma, lack of motivation, no availability of services, emotional concerns, misfit of therapy to needs, time constraints, and negative evaluation. |

| 17 | Killeen et al., 2023 [62] | PTSD; SUD | Trauma-adapted MBRP | 8 weekly sessions | 48 women met the definition of non-completers (attending < 75% sessions); ↓ Lowest rate of completion among unemployed women in the ICS control group, with low FFMQ; ↑ Higher rate of completion in women in TA-MBRP group with low PSS and high FFMQ; ↓ Both the TA-MBRP and ICS groups had low probability of completion for those with high PSS scores. |

| 18 | Somohano & Bowen, 2022 [63] | PTSD-SUD | Trauma-focused and gender-responsive MBRP | 4 weekly sessions (1 h each) | ↓ Craving (PACS) and PTSD symptoms (BSSS) in both conditions over the 12-month follow-up period and effect sizes similar to other PTSD-SUD interventions; ↑ Larger effect of craving and PTSD in both programs after 1 month; ↓ MBRP had lower BSSS at post-test and 1-month follow-up in comparison with TI-MBRP; TI-MBRP acceptability: homework practice was as expected (in both conditions); retention was below the target but 60%; attrition was higher (64%) at post-test and 1-month follow-up in Ti-MBRP than in MBRP. High satisfaction (OCSS). |

| 19 | Possemato et al., 2022 [64] | PTSD | PCBMT | 4 weeks | ↓ PTSD symptoms at post-test; ↓ Depression at 16–24 months follow-up; ↑ Health responsibility; ↑ Stress management, not feeling dominated by symptoms. |

| 20 | Classen et al., 2020 [65] | Childhood trauma, complex PTSD symptoms. | Trauma and the Body Group (TBG) | 20-session program (h for each): | ↑ Body awareness subscale (SBC); ↔ Body dissociation subscale (SBC); ↓ Anxiety (BAI); ↑ Soothing receptivity (SRS); ↔ PCL-5; SDQ-20; DES; PHLMS; IIP-32; ↓ BDI-II. |

| 21 | Gallegos et al., 2020 [66] | In | MBSR | 8 weekly sessions | No statistical power to test between-group differences; Time effects in MBSR group: Improvement but ↔ divided and selective attention (UFOV) ↔ HRV by RMSSD but increase; ↓ DERS; ↓ PCL-5 at post-test and follow-up. Decrease for 50% of the total of participants. |

| 22 | Nguyen-Feng et al., 2020 [67] | PTSD and childhood interpersonal trauma histories | TCTSY | 10 weekly sessions (1 h each) | TCTSY was most efficacious for those with fewer adult-onset interpersonal traumas. Within this subgroup, TCTSY was more effective in reducing PTSD than the active control condition. Clinician-rated PTSD, self-reported PTSD, and emotional control problems, although effects were relatively small-to-moderate. The efficacy of the intervention conditions was less predictable among those with a history of greater adult-onset interpersonal trauma. |

| 23 | Davis et al., 2020 [68] | PTSD | HYP; WLP | 16 weekly sessions | ↓ PCL-5; CAPS-5. |

| 24 | Fortuna et al., 2020 [69] | Dual diagnosis of SUD, depression, anxiety, and chronic stress | IIDEA; CBT + mindfulness Combined interventions | 10 weekly sessions IIDEA trial (1 h each) | Intermediary variables: ↑WAI-SR (alliance), MAAS, and IMR (from a medium-to-small effect size) also at 6-month follow-up; Outcomes: ↓ Urine test and substance use ASI; PCL-10; GAD; PHQ-9; HSCL-20. Qualitative results: Participants found being listened without judgement, learning relaxation and emotional regulation techniques, gaining a sense of self-control, and managing the double diagnosis more useful. |

| 25 | Cox et al., 2019 [70] | Post discharge of critical illness | Mobile and telephone mindfulness program (awareness of breathing; body systems; emotion and mindful acceptance; and awareness of sound) | 4 weekly sessions (1 h each) | Higher drop-out and less CSQ in mobile program. ↓ Similar decrease between mobile and telephone nindfulness in PHQ-9, GAD-7; PTSS at 3 months follow-up; ↓ Education program had a similar impact of mindfulness program on PTSS but less impact than others on PHQ-9 and GAD-7 at 3-months follow-up; ↔ CAMS-R and Brief-COPE. |

| 26 | Miller et al., 2021 [71] | PTSD | Mentoring + mindfulness program (Learning to Breathe, L2B) | 4 mindfulness sessions (30 min each) in 12 weeks | ↓ Child PTSD symptoms; ↓ Emotional impulsivity (DERS-SF); ↓ Difficult in engaging in goal-directed behavior (DERS-SF); ↔ Remaining variables. |

| 27 | Pradhan et al., 2018 [72] | Physical sexual and emotional abuse | TIMBER combined with a single sub-anesthetic dose of ketamine | 12 weekly sessions (1 h each) | ↑ Duration of response in TIMBER-K (compared to TIMBER-Placebo): On average, 34 days with no or minimal PTSD symptoms (PCL, CAPS) (twice longer than the remission with mindfulness therapy alone and 5-fold longer than Ket therapy alone); ↓ PCL and CAPS at relapse were lower than the pre-test; ↔ The average DSR (serine) plasma concentration was lower than basal DSR (but not significant); ↔ Positive correlation, but not significant, between DSR and PTSD severity. |

| 28 | Romaniuk et al., 2023 [73] | PTSD | CMT compared to CFT based on psychoeducational skills | 12 biweekly group sessions (2 h each) | ↓ Fear of compassion (FCS) towards others and self from pre-test to follow-up; ↓ Feelings of self-inadequacy (FSCRS) from pre-test to follow-up; ↓ Levels of external shame (OAS) at follow-up; ↓ PCL-5 in the ex-service personnel; ↓ Anxiety (DASS-21) at follow-up; ↓ Stress (DASS-21) at follow-up; ↔ PCL-5 in the partner group; ↔ Depression (DASS-21); ↑ Social safeness (SSPS) at follow-up; ↑ Quality of life and satisfaction (Q-LES-Q-SF) at post-test but not at follow-up; ↑ Relationship satisfaction (RAS) at post-test but not at follow-up. |

| 29 | Leach & Lorenzon, 2023 [74] | Traumatic experience of domestic violence | TM | 9 individual and group sessions (1–2 h each): total 12 h in 8 weeks | ↓ DASS-21 depression, anxiety, and stress severity scores; ↓ PCL-5 total symptom severity score; ↑ AQoL-8D utility score, superdomain scores, and domain scores (except for pain and senses domain scores). ADVERSE EFFECTS Twelve mild adverse events reported by six participants (i.e., nausea, headache, irritability, weight gain). Two participants self-reported a severe adverse event that they believed was related to the intervention (i.e., cold-sore, body feeling heavy). |

| 30 | Javidi et al., 2023 [75] | PTSD | Self-compassion therapy combined with CBT | 12-session program of individualized CBT-based treatment | ↑ SCS; ↓ K10; ↓ PHQ9; ↓ PCL-C; ↓ WSAS. |

| 31 | Bellehsen et al., 2022 [76] | PTSD | TM | 16 sessions over 12 weeks (1 h each). | ↓ PCL-5; BDI-II; BAI; ISI; ↓ 50% TM group reduced CAPS-5 and 50.0% no longer met the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis after 3 months; ↔ S-anger; ↔ Q-LES/Q-SF. |

| 32 | Gerdes et al., 2022 [77] | PTSD | LKM-S | 1 session audio-taped (1.5 h) | ↓ Self-reported hyperarousal state; ↓ SCL, meaning a reduction in sympathetic arousal; ↔ HRV response was not different from 0, meaning that the intervention may not have increased the parasympathetic activation (unlike what was expected); ↔ Social connectedness; State self-compassion at both pre and post time points were associated with PCL-5, trait self-compassion (SCS), and emotion suppression (ERQ); ↑ HR response (physiological arousal) (not, as expected, a decrease); ↑ HR response to directing compassion towards the self; ↑ Self-compassion state at the end of LKM. |

| 33 | Knabb et al., 2022 [78] | Exposure to crime-related events, physical and sexual experiences, and general disasters | Christian meditative intervention (Lectio Divina) | 2 weeks | ↓ PTSD symptoms; ↔ Positive effect (small effect size); ↔ Christian contentment; ↔ Christian gratitude; ↔ Anxiety, depression, stress (medium effect size). |

| 34 | Hodgdon et al., 2022 [79] | PTSD | IFS Combined interventions | 16 individual sessions (1.5 h each) | ↓ CAPS at post-test and 1-month follow-up; At 1-month follow-up, 92% of participants no longer met criteria for PTSD; ↓ DTS at post-test and 1-month follow-up; ↓ BDI at post-test and 1-month follow-up; ↓ SIDES total score at the 1-month follow-up; ↔ Somatization; ↔ SCS; ↑ Large effect size on trusting and medium effect sizes on attention regulation, self-regulation, and body listening; ↑ Not-sistracting subscale of MAIA just at 1-month follow-up; ↔ No significant time effect for other subscales of MAIA. |

| 35 | Tibbitts et al., 2021 [80] | Not revealed | TIY | From 2 to 10 sessions | ↓ Reported decreased feeling pain or negative emotional states; ↑ Use of self-regulation skills was uniformly higher; ↑ Reported increased awareness of physical sensations (e.g., breathing and muscle movement); ↑ Students in the corrections and reentry sector had the largest benefit after beginning yoga. Adverse effects: For negative emotional states, only a few students reported feeling upset, anxious, or stressed after class. Fewer respondents from substance use treatment retrospectively reported feeling upset and anxious or stressed before yoga class. This group showed the least amount of change in self-regulation skills. |

| 36 | Kananian et al., 2020 [81] | Multiple trauma pre–post displacement | CA-CBT Combined interventions | 12 sessions in 6 weeks (1.30 h each) | ↓ PHQ-9; SSS-8; ↔ PCL-5; ↑ WHOQOL-BREF; ↑ ERS; ↑ GHQ-28 at both follow-up. At 1-year follow-up main effects were maintained |

| 37 | Schuurmans et al., 2021 [82] | PTSD | MUSE | 6 weeks: 2 times a week for 15–20 min | ↓ Basal activity of SNS (sympathetic nervous system); ↔ Reactivity of SNS and PNS (parasympathetic nervous system) to acute stress; ↑ HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) reactivity to acute stress. |

| 38 | Zalta et al., 2020 [83] | PTSD | ITP Combined interventions | 3 weeks: 14 individual sessions of CPT, 13 sessions of group VPT, 13 session group mindfulness adapted from MBSR, and 12 sessions of yoga | ↓ ISI in just 23.4%; ↓ PCL-5-18; PHQ-8; ↔ Baseline ISI did not predict PCL-5 and PHQ-8 across all time points, but larger improvements in ISI were associated with greater improvement in PCL-5 and PHQ. |

| 39 | Bandy et al., 2020 [84] | Several among natural disasters, severe accidents, sexual and criminal victimization, and combat experiences | TM | 4 consecutive days (1.30 h daily) and weekly follow-up meetings and home practices | ↓ PCL-C in experimental group after 15, 60, and 105 days of practice. In this point, PCL-C was not symptomatic anymore; ↓ BDI at both 60 and 105 days; ↓ BDI Depression and PTSD were highly correlated and decreased together through the practice. Regular TM practice predicted. ↓ PCL-C especially during the first 15 days of practice. |

| 40 | Zaccari et al., 2020 [85] | PTSD | Yoga protocol | 10 weeks | ↑ Life satisfaction; ↓ Depression, cortisol; ↔ Cognitive performance. |

| 41 | Ong et al., 2019 [86] | IPV | TSY | 8 weekly sessions (1 h each) | ↓ CAPS-5 (but one for floor effect): reduced number and severity. Enhanced physiological, intrapsychic functioning, emotional benefits, enhanced perceptions of self and others, shift in time perspective, interpersonal relationships, self-care, spiritual benefits, and positive coping strategies. |

| 42 | Reinhardt et al., 2018 [87] | PTSD | Kripalu yoga program | 20 sessions in 10 weeks (1.30 h each) | CAPS-5 up to moderate PTSD symptoms at post-test in yoga group. ↔ Between differences in CAPS, PCL-M, and IES; ↓ Large effect PCL-M (correlated with PCL-C), self-reported PTSD symptoms were reduced in the yoga group (below the cutoff) while marginally increased in the control group, 51% drop out (higher in the yoga group). Self-selectors (from waitlist) improved more than randomized veterans in CAPS and PCL. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scafuto, F.; Quinto, R.M.; Orrù, G.; Lazzarelli, A.; Ciacchini, R.; Conversano, C. Do Contemplative Practices Promote Trauma Recovery? A Narrative Review from 2018 to 2023. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222825

Scafuto F, Quinto RM, Orrù G, Lazzarelli A, Ciacchini R, Conversano C. Do Contemplative Practices Promote Trauma Recovery? A Narrative Review from 2018 to 2023. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222825

Chicago/Turabian StyleScafuto, Francesca, Rossella Mattea Quinto, Graziella Orrù, Alessandro Lazzarelli, Rebecca Ciacchini, and Ciro Conversano. 2025. "Do Contemplative Practices Promote Trauma Recovery? A Narrative Review from 2018 to 2023" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222825

APA StyleScafuto, F., Quinto, R. M., Orrù, G., Lazzarelli, A., Ciacchini, R., & Conversano, C. (2025). Do Contemplative Practices Promote Trauma Recovery? A Narrative Review from 2018 to 2023. Healthcare, 13(22), 2825. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222825