Feasibility of a Person-Centred Nursing Model Targeting Patient and Family Caregiver Needs in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

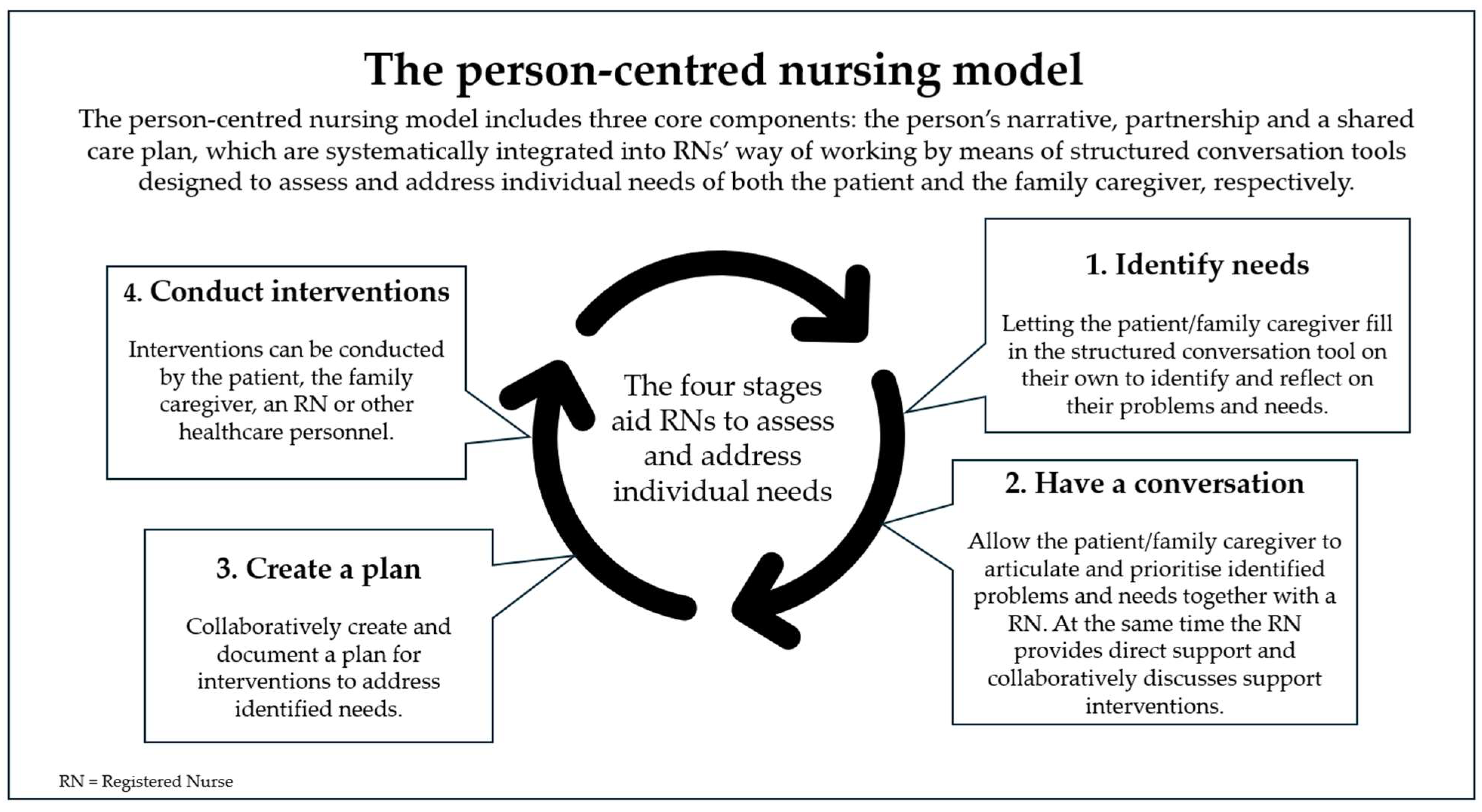

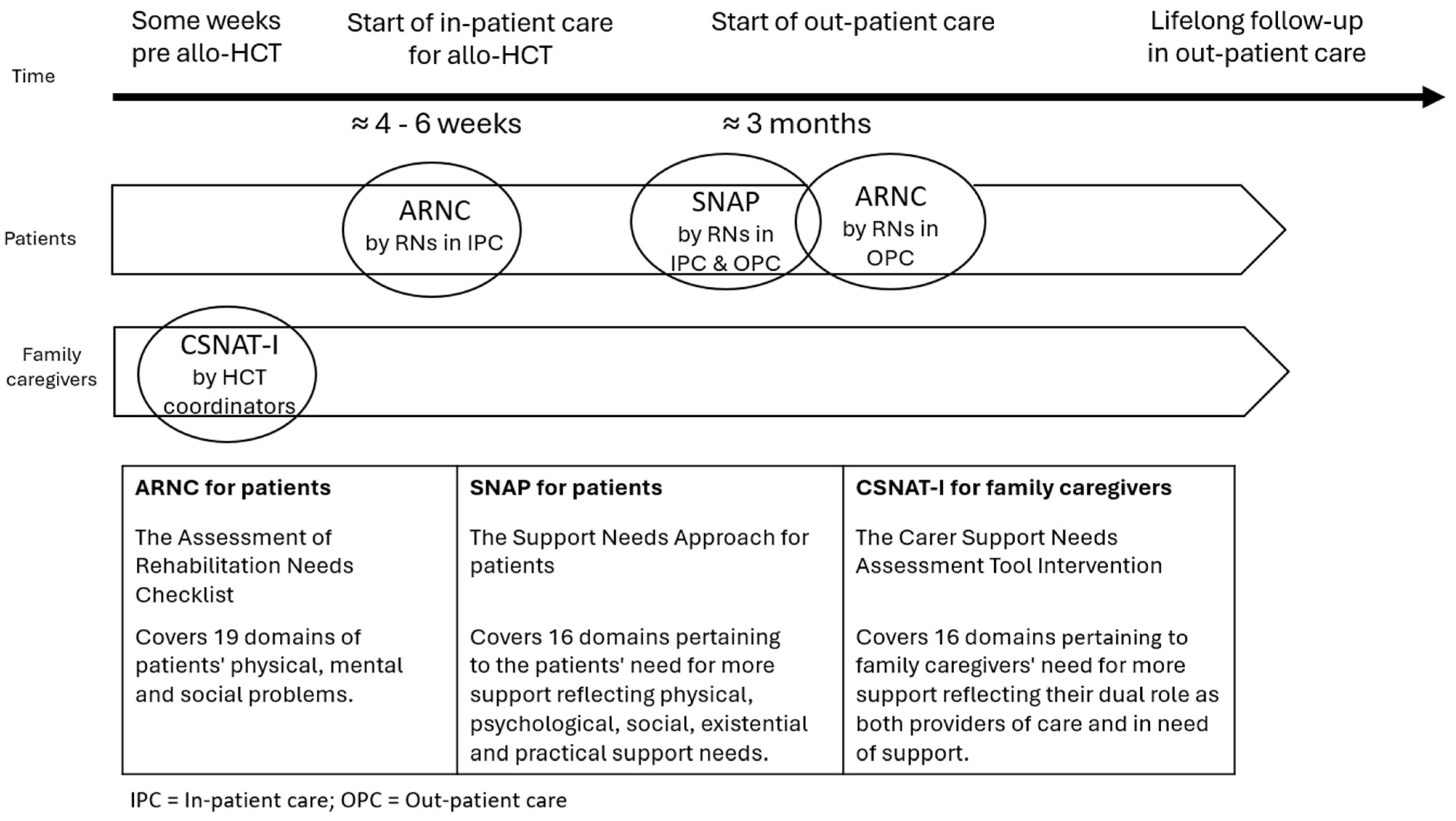

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Procedure

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Practicality of the Model

3.2.1. Practicality of Using the ARNC Tool

3.2.2. Practicality of Using the SNAP Tool

3.2.3. Practicality of Using the CSNAT-I Tool

3.3. Acceptability of the Nursing Model

3.3.1. Overall Experiences of Using the Tools and Subsequent Conversations

3.3.2. Experiences of Using the ARNC Tool

“I think all questions are relevant, I understand why the questions are being asked and feel they are appropriate for the situation.”(Patient 2)

“Needs emerge that would not have been discussed otherwise, or that their biggest problem is not what you thought it would be.”(RN, focus group 2)

“I have heard that they like it a lot, precisely because they are able to sit and reflect on the questions in the tools and become aware of what the real problem is.”(RN, focus group 1)

“It helps you realise which areas you need to focus on, a positive experience of filling in forms, not only important for healthcare but also important for yourself. It makes you think, become more aware of what you should keep an eye on, drinking, urinating, how your skin looks, moving around.”(Patient 17)

“I think that many patients consider sexuality a problem, and that they have a lot of problems in that area, and it feels like an easier approach to that topic, which can perhaps be difficult to bring up, just like that.”(RN, focus group 3)

“The biggest difference I’ve experienced is that you have a lot more conversations about family and relationships, and something that is completely new to me, finances. Something I have never talked to my patients about. Because for me it’s not a problem in inpatient care, but it obviously is.”(RN, focus group 2)

“There are limits to what you are willing to talk about when you have another relative with you, so I felt that it was... a bit of a shame.”(RN, focus group 1)

“It was no help for me to become aware of troublesome problems, probably because I had no problems.”(Patient 24)

“I know one patient who just said no, I don’t have any problems, so... Who thought it wasn’t worth filling in because there’s nothing bothering me.”(RN, focus group 3)

3.3.3. Experiences of Using the SNAP Tool

“It can definitely be a support. I didn’t need it myself, but it’s still good to know how it could have been, good to think for myself whether or not that was the case.”(Patient 16)

“I think the basic idea is very good. I find it a little difficult to put it into a time perspective, when to use it. I think it’s a bit too early, as we’ve been using it right now, during discharge conversations.”(RN, focus group 3)

“It is vague, unclear, I cannot give a precise answer, I do not really understand the purpose of the form, what the aim is, I mostly guess when filling it in. Difficult when leaving hospital, better after six months, a year.”(Patient 2)

“The SNAP tool is perhaps the most difficult to get right. I have tried a few in inpatient care, and I think it ends up completely wrong there. The patients themselves... everyone I have spoken to has said, this is too early, I would like to do this when I get home and have been at home. In outpatient care, I think it should be done a little later, when the patient has been home for a while.”(RN, focus group 1)

3.3.4. Experiences of Using the CSNAT-I Tool

“It was good to be able to put things into words, to talk about what you are thinking about, and the tool felt relevant; I’m sure everyone needs that. I think it’s good that I am involved as a relative and that I have the opportunity for conversation and support.”(Family caregiver 11)

“Yes, it was really great. I think it feels very reassuring to be able to participate in something like this, because then you feel that you are involved in a different way. Yes, well, it’s just that you feel included in some way, perhaps you gain a greater understanding of it because you think a little more about these issues and so on.”(Family caregiver 15)

“Yes, but using this tool provides a good structure. I think it also makes the family caregiver think a little more. That someone puts into words certain things that you might not have thought of otherwise.”(RN, focus group 4)

“It was clear that the family caregivers appreciated having the conversations and feeling that they were seen. Family caregivers were very grateful for having had the conversation and made comments like, ‘yes, but now I have a better understanding of it. Now I feel better.’”(RN, focus group 4)

“It’s about the future, what to expect. That was probably the most... Actually... I think that’s what concerns me the most.”(Family caregiver 12)

“In the best of worlds, two calls would have been best. I wonder if it wouldn’t be better to have a second one afterwards. I get the feeling that they might need more support then.”(RN, focus group 4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendations for Further Research

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Allo-HCT | Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| ARNC | The Assessment of Rehabilitation Needs Checklist |

| EBCD | Experience-based Co-Design |

| CSNAT-I | The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool Intervention |

| GPCC | Gothenburg Centre for Person-centred Care |

| IPC | In-patient care |

| MRC | Medical Research Council |

| OPC | Out-patient care |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| SNAP | The Support Needs Approach for patients |

References

- Karimi-Rozveh, A.; Bishe, E.N.; Mohammadi, T.; Vaezi, M.; Sayadi, L. Preparedness, Uncertainty, and Distress Among Family Caregivers in the Care of Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2025, 52, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, I.d.V.; Kilgour, J.M.; Danby, R.; Peniket, A.; Matin, R.N. “Is this the GVHD?” A qualitative exploration of quality of life issues in individuals with graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplant and their experiences of a specialist multidisciplinary bone marrow transplant service. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, L.V.M.; Holmberg, K.M.; Hagelin, C.L.; Wengström, Y.P.; Bergkvist, K.; Winterling, J. Symptom Burden and Recovery in the First Year After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadfar, N.; Weaver, M.T.; Al-Mansour, Z.; Yi, J.C.; Jim, H.S.; Loren, A.W.; Majhail, N.S.; Whalen, V.; Uberti, J.; Wingard, J.R.; et al. Self-Efficacy for Symptom Management in Long-Term Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cell Survivors. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2022, 28, 606.e1–606.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisch, A.M.; Bergkvist, K.; Alvariza, A.; Årestedt, K.; Winterling, J. Family caregivers’ support needs during allo-HSCT—A longitudinal study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhail, N.S. Long-term complications after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2017, 10, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurkocza, B.; Rezvani, A.; Storb, R.F. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: The state of the art. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2010, 3, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjala, K.L.; Martin, P.J.; Lee, S.J. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3746–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K.; Esser, P.; Scherwath, A.; Schirmer, L.; Schulz-Kindermann, F.; Dinkel, A.; Balck, F.; Koch, U.; Kröger, N.; Götze, H.; et al. Cancer-and-treatment–specific distress and its impact on posttraumatic stress in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lans, M.C.; Witkamp, F.E.; Oldenmenger, W.H.; Broers, A.E. Five Phases of Recovery and Rehabilitation After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Qualitative Study. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, K.; Larsen, J.; Johansson, U.-B.; Mattsson, J.; Fossum, B. Family members’ life situation and experiences of different caring organisations during allogeneic haematopoietic stem cells transplantation-A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloméni, A.; Lapusan, S.; Bompoint, C.; Rubio, M.; Mohty, M. The impact of allogeneic-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on patients’ and close relatives’ quality of life and relationships. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, N.; Moons, P.; Taft, C.; Boström, E.; Fors, A. Observable indicators of person-centred care: An interview study with patients, relatives and professionals. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’sUllivan, A.; Winterling, J.; Kisch, A.M.; Bergkvist, K.; Edvardsson, D.; Wengström, Y.; Hagelin, C.L. Healthcare Professionals’ Ratings and Views of Person-Centred Care in the Context of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Heal. Serv. Insights 2025, 18, 11786329241310735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rafferty, A.M.; Bruyneel, L.; McHugh, M.; Maier, C.B.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; Ball, J.E.; Ausserhofer, D.; et al. Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: Cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlén, J.; Sawatzky, R.; Pettersson, M.; Sarenmalm, E.K.; Larsdotter, C.; Smith, F.; Wallengren, C.; Friberg, F.; Kodeda, K.; Carlsson, E. Preparedness for colorectal cancer surgery and recovery through a person-centred information and communication intervention—A quasi-experimental longitudinal design. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralong, A.; Herling, M.; Holtick, U.; Scheid, C.; Hellmich, M.; Hallek, M.; Pauli, B.; Reimer, A.; Schepers, C.; Simon, S.T. Developing a supportive and palliative care intervention for patients with allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Protocol of a multicentre mixed-methods study (allo-PaS). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donetto, S.; Pierri, P.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. Experience-based Co-design and Healthcare Improvement: Realizing Participatory design in the Public Sector. Des. J. 2015, 18, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E.; Carlsson, J.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Johansson, I.-L.; Kjellgren, K.; et al. Person-centered care--ready for prime time. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson-Nevo, E.; Fogelkvist, M.; Lundqvist, L.-O.; Ahlgren, J.; Karlsson, J. Validation of the Assessment of Rehabilitation Needs Checklist in a Swedish cancer population. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardener, A.C.; Ewing, G.; Mendonca, S.; Farquhar, M. Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP) tool: A validation study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, G.; Austin, L.; Diffin, J.; Grande, G. Developing a person-centred approach to carer assessment and support. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2015, 20, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, G.; Brundle, C.; Payne, S.; Grande, G. The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: A validation study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 46, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelin, C.L.; Holm, M.; Axelsson, L.; Rosén, M.; Norell, T.; Godoy, Z.S.; Farquhar, M.; Ewing, G.; Gardener, A.C.; Årestedt, K.; et al. The Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP): Content validity and response processes from the perspective of patients and nurses in Swedish specialised palliative home care. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvariza, A.; Holm, M.; Benkel, I.; Norinder, M.; Ewing, G.; Grande, G.; Håkanson, C.; Öhlen, J.; Årestedt, K. A person-centred approach in nursing: Validity and reliability of the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisch, A.M.; Bergkvist, K.; Adalsteinsdóttir, S.; Wendt, C.; Alvariza, A.; Winterling, J. A person-centred intervention remotely targeting family caregivers’ support needs in the context of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—A feasibility study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9039–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Venetis, M.K.; Robinson, J.D.; Turkiewicz, K.L.; Allen, M. An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: A meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 77, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, L.; Palacios, L.G.; Pelger, R.; Elzevier, H. Can the provision of sexual healthcare for oncology patients be improved? A literature review of educational interventions for healthcare professionals. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epner, D.E.; Baile, W.F. Difficult conversations: Teaching medical oncology trainees communication skills one hour at a time. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S.; Johnson, C.; Waller, A.; Currow, D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: A review. J. Oncol. Pr. 2013, 9, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, F.; Arnaboldi, P.; Santoro, L.; D’Anna, E.; Beltrami, C.; Mazzoleni, E.; Veronesi, P.; Maggioni, A.; Didier, F. The effects of a multimodal training program on burnout syndrome in gynecologic oncology nurses and on the multidisciplinary psychosocial care of gynecologic cancer patients: An Italian experience. Palliat. Support. Care 2012, 11, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garment, A.R.; Lee, W.W.; Harris, C.; Phillips-Caesar, E. Development of a structured year-end sign-out program in an outpatient continuity practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients n = 36 | Family Caregivers n = 32 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Women | 14 (39) | 24 (75) |

| Men | 22 (61) | 8 (25) |

| Age at allo-HCT | ||

| Median (min-max) | 55 (19–77) | 52 (21–72) |

| The family caregivers’ relationship to the patient | ||

| Partner | 22 (69) | |

| Parent | 3 (9) | |

| Child | 3 (9) | |

| Sibling | 4 (13) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Lower education | 13 (42) | 15 (47) |

| Higher education (College/University) | 18 (58) | 17 (53) |

| Living situation, n (%) | ||

| Living with someone | 22 (71) | 27 (84) |

| Living alone | 7 (23) | 5 (16) |

| Missing | 2 (6) | - |

| Children under 18, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 9 (29) | 9 (28) |

| No | 21 (68) | 22 (69) |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Country of birth, n (%) | ||

| Sweden | 26 (84) | 29 (91) |

| Other | 5 (16) | 3 (9) |

| Positive n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Negative n (%) | Positive & Negative n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARNC | Patients, n = 16 | 7 (44) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (31) | 2 (12.5) |

| RNs, n = 16 | 10 (62.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (37.5) | |

| SNAP | Patients, n = 16 | 2 (12.5) | 5 (31) | 5 (31) | 4 (2.5) |

| RNs, n = 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | |

| CSNAT-I | Family caregivers, n = 16 | 10 (63) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (31) |

| RNs, n = 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kisch, A.M.; Eriksson, L.V.; O’Sullivan, A.; Shahriari, A.; Bergkvist, K.; Hagelin, C.L.; Winterling, J. Feasibility of a Person-Centred Nursing Model Targeting Patient and Family Caregiver Needs in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192463

Kisch AM, Eriksson LV, O’Sullivan A, Shahriari A, Bergkvist K, Hagelin CL, Winterling J. Feasibility of a Person-Centred Nursing Model Targeting Patient and Family Caregiver Needs in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192463

Chicago/Turabian StyleKisch, Annika Malmborg, Linda V. Eriksson, Anna O’Sullivan, Aida Shahriari, Karin Bergkvist, Carina Lundh Hagelin, and Jeanette Winterling. 2025. "Feasibility of a Person-Centred Nursing Model Targeting Patient and Family Caregiver Needs in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192463

APA StyleKisch, A. M., Eriksson, L. V., O’Sullivan, A., Shahriari, A., Bergkvist, K., Hagelin, C. L., & Winterling, J. (2025). Feasibility of a Person-Centred Nursing Model Targeting Patient and Family Caregiver Needs in Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Healthcare, 13(19), 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192463