The Effect of Workplace Mobbing on Positive and Negative Emotions: The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience Among Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Emergency Department Nurses: A High-Risk Group

1.3. Mobbing in Healthcare Settings and Emergency Departments

1.4. Mobbing and Emotional Consequences

1.5. Emotional Experience in Emergency Departments

1.6. Psychological Resilience as a Mediator

1.7. Scope and Aims of the Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Place of Conduct

- High volume of emergency admissions, ensuring exposure to high-stress clinical environments, a factor known to influence workplace behaviors and dynamics [55];

- Presence of full-time ED nursing staff, ensuring consistency in participants’ work settings and minimizing variability due to shift-based or temporary personnel [56];

- Institutional willingness to participate, including administrative approval and ethical clearance, in accordance with standard protocols for healthcare research [57];

2.3. Study Sample

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Were employed full-time in an ED at one of the participating hospitals;

- Were licensed nursing personnel, including registered nurses and nurse assistants [61];

- Had a minimum of six months’ continuous service in their current ED position (to ensure adequate exposure to the environment) [62];

- Had sufficient proficiency in Greek to understand and complete the questionnaire;

- Provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Were on temporary leave, extended absence, or probationary contracts at the time of data collection;

- Held administrative or exclusively supervisory roles with minimal direct patient contact;

- Had less than six months of experience in the ED setting;

- Declined or failed to provide informed consent;

- Had participated in a similar survey within the past year (to reduce survey fatigue and response bias) [63].

2.4. Study Instruments

2.4.1. Workplace Psychological Violence Behavior (WPVB) Questionnaire

2.4.2. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

2.4.3. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)

- Personal competence, high standards, and tenacity—reflecting self-efficacy, persistence, and confidence in one’s problem-solving abilities.

- Trust in one’s instincts and tolerance of negative affect—encompassing adaptive emotional processing and intuitive decision-making.

- Positive acceptance of change and secure relationships—indicating flexibility, adaptability, and the ability to maintain meaningful interpersonal connections.

- Sense of control—measuring one’s perceived influence over life circumstances.

- Spiritual influences—capturing the role of faith or existential beliefs as sources of strength.

2.4.4. Demographic Questionnaire

2.5. Data Collection Process—Research Ethics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- Workplace psychological violence behaviors (WPVB) subscale scores were computed by summing the responses within each domain (item range: 0–5), yielding both domain-specific and total scores, with higher scores reflecting greater exposure to psychological violence in the workplace.

- The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25) total resilience score was derived by summing all 25 items (score range: 0–100), where higher scores indicate greater psychological resilience [5].

- The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scores were calculated separately for the positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) subscales. Each subscale consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “very slightly or not at all” to 5 = “extremely”), with scores ranging from 10 to 50 per subscale. Higher PA scores reflect greater experience of positive emotions, while higher NA scores indicate more frequent negative emotional states [4].

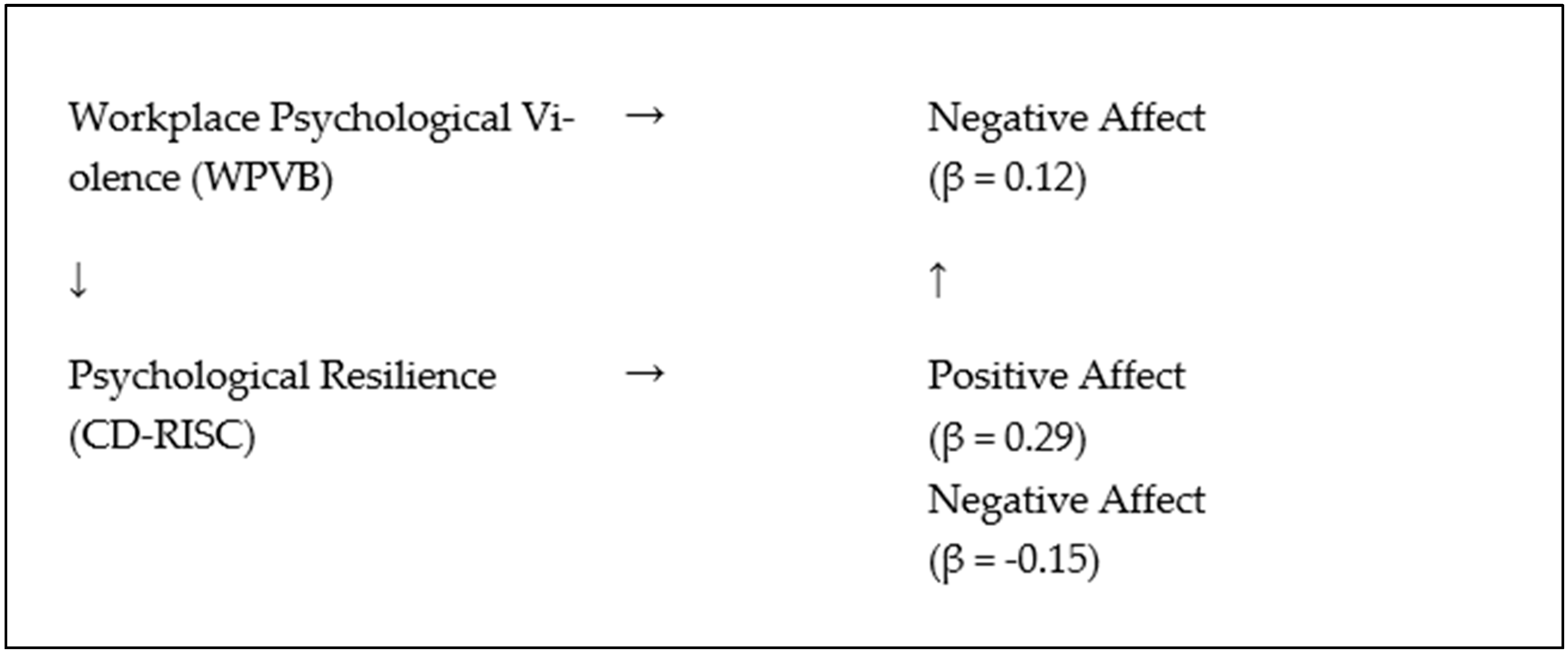

- Workplace psychological violence (WPVB) functions as the independent variable;

- Resilience (CD-RISC-25) serves as the mediating variable;

- Positive and Negative Affect (PANAS) are considered the outcome variables.

3. Results

3.1. Specific Characteristics

3.2. Table 6—Mediation Analysis: Resilience as a Mediator

| Predictor Variable | Indirect Effect (Via Resilience) | 95% CI (Indirect) | Direct Effect | 95% CI (Direct) | Mediation? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total WPVB Score | 0.029 | −0.001 to 0.080 | 0.121 | 0.064 to 0.178 | ✗ Not significant |

| Attack on Personality | 0.088 | −0.010 to 0.214 | 0.409 | 0.218 to 0.601 | ✗ Not significant |

| Attack on Professional Status | 0.098 | 0.008 to 0.246 | 0.319 | 0.136 to 0.502 | √ Partial mediation |

| Individual’s Isolation from Work | 0.077 | −0.008 to 0.237 | 0.310 | 0.157 to 0.463 | ✗ Not significant |

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings of the Study—Summary

4.2. Detailed Discussion of the Research Findings

4.3. Resilience as a Protective Factor

4.4. Impact of Workplace Psychological Violence on Emotional Health

4.5. Sociodemographic and Health Factors Influencing Emotional Affect

4.6. Implications for Practice

4.7. Implications and Strengths

4.8. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD-RISC | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

| DYPE | Regional Health Authority |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| WPVB | Workplace Psychologically Violent Behaviors Questionnaire |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| β | Beta Coefficient (used in regression analysis) |

| α | Cronbach’s Alpha (internal consistency reliability) |

| ρ (rho) | Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient |

| r | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

| p-value | Probability Value (used to assess statistical significance) |

Appendix A

| Attack on Personality | Attack on Professional | Individual’s Isolation from Work | Direct Attack | Total WPVB Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attack on personality | 1.00 | 0.68 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.35 ** | 0.79 *** |

| Attack on professional | 1.00 | 0.61 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.91 *** | |

| Individual’s isolation from work | 1.00 | 0.45 *** | 0.80 *** | ||

| Direct attack | 1.00 | 0.63 *** | |||

| Total WPVB score | 1.00 |

References

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.L.; Rea, R.E. Workplace bullying: Concerns for nurse leaders. J. Nurs. Adm. 2009, 39, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Arcangeli, G.; Mucci, N.; Cupelli, V. Economic stress in the workplace: The impact of fear of the crisis on mental health. Work 2015, 51, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, P.L.; Brannan, J.D.; De Chesnay, M. Resilience in nurses: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Newman, J.; McFann, K.K.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, S.M.; Al-Shatti, A.K.; Kamal, S.; El-Gerges, N.; Al-Raqem, M. Violence against nurses in healthcare facilities in Kuwait. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, J.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Causes and consequences of occupational stress in emergency nurses: A longitudinal study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, S.; Girdler, S.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F. Paediatric nurses’ work-related stress and supportive factors: A scoping review. J. Child Health Care 2013, 17, 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, S.; Tyrrell, M. Stress in emergency departments: Experiences of nurses and doctors. Emerg. Nurse 2011, 19, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purpora, C.; Blegen, M.A. Horizontal violence and the quality and safety of patient care: A conceptual model. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 306948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L. International perspectives on workplace bullying among nurses: A review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2009, 56, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Khatri, N. Bullying among nurses and its relationship with organizational culture and leadership: A review of the literature. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2015, 5, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: An intervention to enhance the effectiveness of nurses’ coping with work-related stress. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2014, 25, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, C.; Miller, K.J.; El-Ansary, D.; Remedios, L.; Hosseini, A.; McLeod, S. Replacing stressful challenges with positive coping strategies: A resilience program for clinical placement learning. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2015, 20, 1303–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, S.R.; Mawn, B. Bullying in the workplace—A qualitative study of newly licensed registered nurses. AAOHN J. 2010, 58, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschgler, K.; Ruiz-Hernández, J.A.; Llor-Esteban, B.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.A. Vertical and lateral workplace bullying in nursing: Development of the Health Workplace Scale. J. Interpers. Violence 2013, 28, 2389–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Mancuso, S.; Fiz Perez, F.; Mucci, N.; Cupelli, V.; Arcangeli, G. Bullying among nurses and its relationship with burnout and organizational climate. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016, 22, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisa, S.; Dziegielewski, S.F. Employee bullying in the workplace: A study of Turkish workers. J. Health Soc. Policy 2009, 22, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.-Q.; Wu, J.; Yuan, L.-X.; Zhang, S.-C.; Jing, M.-J.; Zhang, H.-S.; Luo, J.-L.; Lei, Y.-X.; Wang, P.-X. Workplace Violence and Job Performance among Community Healthcare Workers in China: The Mediator Role of Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14872–14886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Vázquez, I.; Cajachagua Castro, M.; Morales-García, W.C. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of job satisfaction: The mediating role of conflict management in nurses. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1249020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, D.; Rodwell, J. Psychosocial antecedents and consequences of workplace aggression for hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2012, 44, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatuna, I.; Gök, S.; Bozbay, G. Relationship between mobbing exposure and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of psychological resilience. Work 2020, 66, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Aristidou, L.; Mpouzika, M.D.; Karanikola, M.N. Exploration of Workplace Bullying in Emergency and Critical Care Nurses in Cyprus. Connect World Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 13, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, B. Psychological Workplace Violence and Health Outcomes in South Korean Nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2022, 70, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Liang, H.F.; Han, C.Y.; Chen, L.C.; Hsieh, C.L. Professional resilience among nurses working in an overcrowded emergency department in Taiwan. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 42, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Moss, M. A qualitative study of resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Profit, J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Satele, D.V.; Sinsky, C.A.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Tutty, M.A.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Grau, A.L. The influence of personal dispositional factors and organizational resources on workplace violence, burnout, and health outcomes in new graduate nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.L.; Huang, C.T.; Tseng, Y.H. How Emergency Nurses Develop Resilience in the Context of Workplace Violence: A Grounded Theory Study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J.; Riley, K.N. A social-cognitive-behavioral model of academic predictors of adolescents’ life satisfaction. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2008, 23, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Raphael, D.; Mackay, L.; Smith, M.; King, A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Wang, H.H.; Ma, S.C.; Chang, H.Y. The mediating effect of resilience on the relationship between workplace bullying and work-related outcomes among nurses in Taiwan. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2021, 34, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Arrogante, O.; Aparicio-Zaldivar, E. Burnout and Health among Critical Care Professionals: The Mediational Role of Resilience. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2017, 42, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A. The impact of workplace bullying on nurses’ psychological well-being and the mediating role of psychological resilience. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 10, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hegney, D.G.; Rees, C.S.; Eley, R.; Osseiran-Moisson, R.; Francis, K. The contribution of individual psychological resilience in determining the professional quality of life of Australian nurses. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.; Crawford, T.N.; Hulse, B.; Polivka, B.J. Resilience, moral distress, and workplace engagement in emergency department nurses. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şimşek, K. Investigation of the effect of secondary traumatic stress on psychological resilience in emergency nurses: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Chi, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zeng, L.; Peng, H. Experiences of compassion fatigue among Generation Z nurses in the emergency department: A qualitative study in Shanghai, China. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-N.; Jiang, X.-M.; Zheng, Q.-X.; Lin, F.; Chen, X.-Q.; Pan, Y.-Q.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, R.-L.; Huang, L. Mediating effect of resilience between social support and compassion fatigue among intern nursing and midwifery students during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Han, K. Moderating effects of structural empowerment and resilience in the relationship between nurses’ workplace bullying and work outcomes: A cross-sectional correlational study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, K.A. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid. Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest 2020, 158, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, M.S. Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies. Indian J. Dermatol. 2016, 61, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.D.; Kutney-Lee, A.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffield, C.; Diers, D.; O’Brien-Pallas, L.; Aisbett, C.; Roche, M.; King, M.; Aisbett, K. Nursing staffing, nursing workload, the work environment and patient outcomes. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2011, 24, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C.A.; Cummings, G.G.; Grau, A.L. Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: The value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nurs. Econ. 2010, 28, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S.V.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Punnett, L.; Nannini, A. Work environment and nursing staff well-being: An integrative review. Work 2016, 54, 529–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J. Public Health 2005, 27, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, A.; Yildirim, D. Development and psychometric evaluation of workplace psychologically violent behaviours instrument. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 17, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Koinis, A.; Velonakis, E.; Tzavara, C.; Tzavella, F.; Tziaferi, S. Psychometric properties of the workplace psychologically violent behaviors-WPVB instrument. Translation and validation in Greek health Professionals. AIMS Public Health 2019, 6, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 15, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaka, M.A. Guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Wong, C.A.; Grau, A.L. The influence of authentic leadership on newly graduated nurses’ experiences of workplace bullying, burnout and retention outcomes: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Ying, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z. The effectiveness of a workplace violence prevention strategy based on situational prevention theory for nurses in managing violent situations: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023, 23, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Helmreich, I.; König, J.; Chmitorz, A.; Wessa, M.; Lieb, K. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Cooper, C. Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, G.; Jackson, D.; Wilkes, L.; Vickers, M.H. Personal resilience in nurses and midwives: Effects of a work-based educational intervention. Contemp. Nurse 2012, 45, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Guo, N.; Han, Q.; Qian, Y.; Xi, H.; Wang, L. Long-Term Effect of a Comprehensive Active Resilience Education (CARE) Program for Increasing Resilience in Emergency Nurses Exposed to Workplace Violence: A Secondary Analysis of a 12-Week Follow-up Study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, J.A.; Demarco, R.; DiFazio, R. Bullying, harassment, and horizontal violence in the nursing workforce: The state of the science. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2010, 28, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaheri, A.; Bartram, T.; Leggat, S.G. Bullying in the emergency department: Associations with resilience and negative affect. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8504. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D.; Burnard, P.; Coyle, D.; Fothergill, A.; Hannigan, B. Stress and burnout in community mental health nursing: A review of the literature. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2000, 7, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallin, A. Interdisciplinary practice—A matter of teamwork: An integrated literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2001, 10, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.; Dollard, M.F.; Richards, P.J. A National Standard for Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC): PSC 41 as the Benchmark for Low Risk of Job Strain and Depressive Symptoms. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter, M.P.; Laschinger, H.K.; Day, A.; Oore, D.G. The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, G.; Jackson, D.; Wilkes, L.; Vickers, M.H. A work-based mindfulness intervention for nurses: A pilot study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Leiter, M.P.; Day, A.; Gilin, D. Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: Impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males | 15 | 15.7 |

| Females | 75 | 84.3 | |

| Educational level | 2-year college | 6 | 6.7 |

| Technological University | 64 | 71.1 | |

| University | 5 | 5.6 | |

| MSc | 12 | 13.3 | |

| PhD | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Family status | Unmarried | 16 | 17.8 |

| Married | 72 | 80.0 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 2.2 | |

| Have children | No | 23 | 25.6 |

| Yes | 67 | 74.4 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 23 | 34.8 |

| 2 | 37 | 56.1 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9.1 | |

| Living | Alone | 14 | 15.6 |

| With others | 76 | 84.4 | |

| Professional | Nurse | 89 | 98.9 |

| Assistant nurse | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Educational level of nurses | Secondary education | 6 | 6.7 |

| Technological university | 74 | 82.2 | |

| University | 10 | 11.1 | |

| Location | VOLOS | 19 | 21.3 |

| KARDITSA | 25 | 28.1 | |

| LARISSA | 21 | 23.6 | |

| TRIKALA | 24 | 27.0 | |

| Health status | Very poor | 5 | 5.6 |

| Poor | 5 | 5.6 | |

| Not poor. nor good | 10 | 11.1 | |

| Good | 47 | 52.2 | |

| Very good | 23 | 25.6 | |

| Health problems | 19 | 21.1 | |

| If yes, define | Heart problems | 3 | 15.8 |

| Arthritis or rheumatism | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Emphysema or chronic bronchitis | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cataract | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Bone fracture or crack | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Leg problems | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hypertension | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Cancer | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Diabetes | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Stroke | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Chronic mental health problems | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 43.1 | 8.4 | |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | 35.00 | 100.00 | 66.38 (12.83) | 66.5 (58–74) | 0.93 |

| Positive feelings subscale (PANAS) | 13.00 | 46.00 | 33.83 (5.35) | 34.5 (30–37) | 0.85 |

| Negative feelings subscale (PANAS) | 10.00 | 38.00 | 17.8 (6.02) | 17 (13–21) | 0.85 |

| Attack on personality | 0.00 | 29.00 | 4.78 (6.37) | 2 (0–6) | 0.87 |

| Attack on professional | 0.00 | 28.00 | 5.74 (6.51) | 3 (1–8) | 0.86 |

| Individual’s isolation from work | 0.00 | 45.00 | 5.82 (7.61) | 4 (1–7) | 0.89 |

| Direct attack | 0.00 | 19.00 | 1.52 (3.38) | 0 (0–2) | 0.78 |

| Total WPVB score | 0.00 | 110.00 | 17.87 (21.12) | 9 (5–23) | 0.95 |

| Positive Feelings Subscale (PANAS) | Negative Feelings Subscale (PANAS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | r | 0.74 | −0.46 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Attack on personality | rho | −0.02 | 0.32 |

| p | 0.884 | 0.002 | |

| Attack on professional | rho | −0.12 | 0.27 |

| p | 0.258 | 0.011 | |

| Individual’s isolation from work | rho | −0.17 | 0.26 |

| p | 0.108 | 0.015 | |

| Direct attack | rho | −0.08 | 0.37 |

| p | 0.430 | <0.001 | |

| Total WPVB score | rho | −0.13 | 0.33 |

| p | 0.234 | 0.001 | |

| Dependent Variable: Positive Feelings | β+ | SE++ | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Females vs. Males) | −1.45 | 1.05 | 0.173 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.929 |

| Educational level 1 | −0.50 | 0.45 | 0.268 |

| Married (yes vs. no) | −1.49 | 1.34 | 0.268 |

| Have children (yes vs. no) | 0.53 | 1.31 | 0.690 |

| Living (with others vs. alone) | 0.35 | 1.43 | 0.807 |

| Health problems (yes vs. no) | 0.13 | 0.95 | 0.888 |

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | 0.29 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Total WPVB score | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.054 |

| Predictor Variable | β | SE | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Females vs. Males) | −1.25 | 1.49 | 0.403 | — |

| Age | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.343 | — |

| Educational level 1 | −1.38 | 0.63 | 0.031 | Significant − less education = more negative feelings |

| Married (yes vs. no) | −0.37 | 1.89 | 0.844 | — |

| Have children (yes vs. no) | 1.75 | 1.85 | 0.347 | — |

| Living (with others vs. alone) | −1.59 | 2.01 | 0.431 | — |

| Health problems (yes vs. no) | 3.49 | 1.34 | 0.011 | Significant − health issues = more negative feelings |

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | −0.15 | 0.04 | 0.001 | Highly significant − more resilience = fewer negative feelings |

| Total WPVB score | 0.12 | 0.03 | <0.001 | Highly significant − more victimization = more negative feelings |

| Attack on personality | 0.41 | 0.10 | <0.001 | Highly significant − strong impact |

| Attack on professional | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.001 | Significant |

| Individual’s isolation from work | 0.31 | 0.08 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Direct attack | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.137 | —Not significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koinis, A.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kouroutzis, I.; Papathanasiou, I.; Anagnostopoulou, D.; Androutsakos, I.; Papandreou, M.; Katsaiti, I.; Tsioumas, N.; Mourtziapi, M.; et al. The Effect of Workplace Mobbing on Positive and Negative Emotions: The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience Among Nurses. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151915

Koinis A, Papathanasiou IV, Kouroutzis I, Papathanasiou I, Anagnostopoulou D, Androutsakos I, Papandreou M, Katsaiti I, Tsioumas N, Mourtziapi M, et al. The Effect of Workplace Mobbing on Positive and Negative Emotions: The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience Among Nurses. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151915

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoinis, Aristotelis, Ioanna V. Papathanasiou, Ioannis Kouroutzis, Iokasti Papathanasiou, Dimitra Anagnostopoulou, Ioannis Androutsakos, Maria Papandreou, Ioulia Katsaiti, Nikolaos Tsioumas, Melpomeni Mourtziapi, and et al. 2025. "The Effect of Workplace Mobbing on Positive and Negative Emotions: The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience Among Nurses" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151915

APA StyleKoinis, A., Papathanasiou, I. V., Kouroutzis, I., Papathanasiou, I., Anagnostopoulou, D., Androutsakos, I., Papandreou, M., Katsaiti, I., Tsioumas, N., Mourtziapi, M., Sarafis, P., & Malliarou, M. (2025). The Effect of Workplace Mobbing on Positive and Negative Emotions: The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience Among Nurses. Healthcare, 13(15), 1915. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151915