Abstract

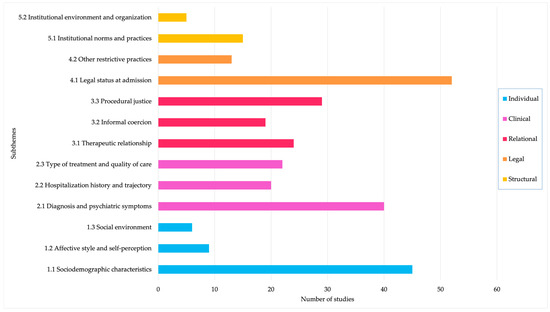

Background/Objectives: Perceived coercion has been associated with significant negative outcomes, including service avoidance and psychological distress. Despite growing interest, no recent comprehensive review has mapped the full range of factors influencing this experience. This scoping review aimed to synthesize and present the state of knowledge on the factors associated with perceived coercion by adults receiving psychiatric care. Methods: Following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, a systematic search of five databases and grey literature was conducted for publications from 1990 to 2025 in English and French. A total of 143 sources were included and thematically analyzed. Consultation with experts and individuals with lived experience enriched the interpretation of findings. Results: Five categories of factors were identified: individual, clinical, relational, legal, and structural. Relational and legal factors were most consistently associated with perceived coercion, while individual and clinical factors showed inconsistent findings. Structural influences were underexamined but significantly shaped the experiences of the individuals receiving care. Conclusions: Perceived coercion arises from a complex dynamic of individual, relational, and systemic influences. Reducing coercion requires moving beyond individual-level factors to address structural conditions and policy frameworks. Future research should prioritize qualitative and intersectional approaches and amplify the voices of those most affected by coercive practices in psychiatric care.

1. Introduction

Coercion is still a central part of mental health and psychiatric care. Despite ongoing controversy and ethical debates, as well as various initiatives to reduce its use [1], the prevalence of coercion remains high [2,3,4,5,6]. In psychiatric and mental health literature, coercion is often presented as a complex concept described in three forms: formal, informal, and perceived [7]. Formal coercion refers to the use of legally regulated coercive measures such as involuntary hospitalization, seclusion, and restraints [8]. Informal coercion consists of a range of strategies predominantly used by health professionals, often aimed at promoting treatment adherence or other behaviors aligned with normative expectations [3]. Persuasion, inducement, and threats are examples of informal coercion [9]. The current review will focus on perceived coercion, which can be described as the person’s subjective, yet valid, experience of being coerced, regardless of the presence of formal or informal coercion [5].

Although less studied than other forms of coercion, perceived coercion is nevertheless commonly reported by a large number of persons receiving psychiatric care. Studies have shown that up to 74 to 80% of involuntarily hospitalized individuals, and 22 to 25% of those voluntarily admitted for a mental health issue, report perceiving coercion [5,10]. Perceived coercion has many consequences, such as an increased risk of suicide after discharge [11], avoidance of mental health services [12], and feelings of dehumanization and isolation [5]. Yet, the understanding of how this phenomenon is experienced and why it is so prevalent remains limited.

Many studies have examined which factors could be associated with perceived coercion, for example, by studying the influence of age [13], legal status [14], the quality of interactions with health professionals [15], or procedural justice [16]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no review of the literature offers a comprehensive portrait of this phenomenon. A number of literature reviews have looked at perceived coercion, as a main or secondary outcome, by exploring the impacts of seclusion and restraint [17,18], forced medication [18], the patients’ legal status [5,19,20,21,22], and the patients’ decision-making capacity [23]. We found only one systematic review, dating back to 2011, that considered other factors, such as the patients’ quality of life or their sociodemographic characteristics [20]. This review had several limitations, including the selection of studies in English only and the absence of grey literature. Furthermore, more recent studies suggest that perceived coercion may be linked to other factors such as the perception of fairness and justice during treatment, also known as procedural justice [15,16,24,25]. Considering the lack of literature reviews that take into account all the factors that may be associated with perceived coercion, a more global and recent portrait of this subject is needed.

A scoping review method was used to present the state of knowledge on the factors associated with perceived coercion by adults receiving psychiatric care. The research question that was asked is:

What factors are associated with perceived coercion by adults receiving psychiatric care?

2. Methods and Analysis

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews was followed [26]. Its clear guidelines allowed the reviewers to conduct a thorough review that may be easily replicated to ensure its validity. The nine steps of the JBI methodology were followed: (1) defining the objectives, (2) developing the inclusion criteria, (3) planning the evidence searching, selection, data extraction, and presentation, (4) searching the evidence, (5) selecting the evidence, (6) extracting the evidence, (7) analyzing the evidence, (8) presenting the results, and (9) summarizing the evidence, with the addition of a 10th step of consultation with relevant collaborators to add rigor [27,28]. The consultation took place after the initial data analysis (step 7), during which preliminary results were presented, reviewed, and discussed through direct conversation and critical revision of the written document with key contributors: a person with lived experience of psychiatric care (EH) and a researcher specialized in the field of psychiatry and perceived coercion (BS). Notably, four of the authors of this review also have experience as psychiatric nurses or nurse-managers in various care settings (CLD, VB, PPL, and SSR). The Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [29] was followed (see Supplementary Table S1). The protocol was initially registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/kc7gw) and consequently published [30].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

In accordance with the JBI methodology for the development of a scoping review, this review applied specific eligibility criteria for the inclusion of literature based on the type of participants, concept, context, and type of evidence.

The target population was adults aged 18 years or older who are receiving or have received psychiatric care. While no upper age limit was applied, literature focusing specifically on geriatric psychiatry was excluded due to the particularities associated with this subspecialty, such as physical comorbidities and neurodegenerative disorders, which would have introduced complexity beyond the scope of this review and made it more difficult to synthesize findings in relation to general psychiatric care. Similarly, literature on intellectual disability, perinatal psychiatry, and eating disorders was excluded. In the case of eating disorders, this exclusion was due to the specific nature of this subspecialty, which often involves considerations related to physical health (e.g., medical stabilization, nutrition) that are not generalizable to psychiatric care more broadly. In contrast, subspecialties such as psychiatric rehabilitation, forensic psychiatry, community psychiatry, and addiction psychiatry were considered eligible, as they fall within the scope of general psychiatric services and typically share more comparable contexts, practices, and populations with adult psychiatric care. Addiction psychiatry was included because individuals receiving care in these settings are commonly treated within psychiatric services and subject to similar legal and clinical dynamics concerning perceived coercion.

Literature on the factors associated with perceived coercion, understood as the subjective and personal experience of coercion, was included in this review. This association could be measured quantitatively using specific scales (e.g., The MacArthur Admission Experience Survey) or explored qualitatively through participant narratives and themes related to their experience of coercion. All types of mental health care settings were included, whether inpatient, outpatient, or community based.

The types of evidence considered encompassed a broad range of literature, including but not limited to primary studies (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods), literature reviews (such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses), conference abstracts, guidelines, theoretical articles, and grey literature (e.g., theses). Only sources available in full text in either French or English were included.

2.2. Search Strategy

A search was conducted in five databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PUBMED, EMBASE, and PsychINFO by a librarian specialized in mental health and psychiatry (MD). Based on two main concepts derived from the research questions, “perceived coercion” and “psychiatry/mental illness”, a list of terms was generated, from which a search was conducted using descriptors and keywords (Table 1). Years of publication were limited to 1990 and onward, considering the first studies focusing specifically on perceived coercion were published after this date. A search was then conducted specifically in mental health periodicals to identify articles that might not be in the databases. A search was also conducted to identify grey literature by searching via Google, OpenGrey, university thesis sites, and government agencies (see Supplementary Table S2). The first literature search was conducted in December 2022 and was updated in January 2025 for both databases and grey literature.

Table 1.

Example of a search conducted in PUBMED.

2.3. Source of Evidence Selection

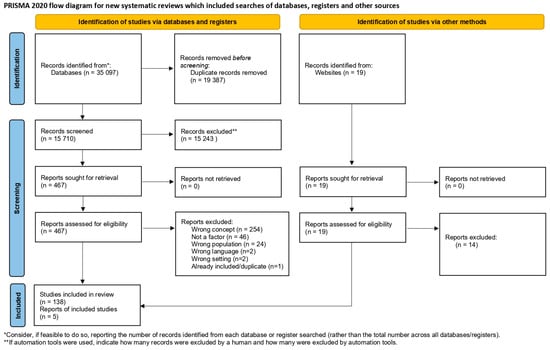

All citations were uploaded in Covidence software (2025). After removing duplicates, a first selection was completed based on title and abstract examination of the articles for assessment against the inclusion criteria. The selection was conducted independently by two reviewers (CLD and SSR) following a pilot test. A second selection was based on full-text examination of the literature selected in the first stage and was completed by two reviewers (CLD and EH). If any disagreements arose between the reviewers at any stage of the selection process, they were resolved through discussion to reach a final decision. The first author, who conceptualized the project, discussed any disagreements with the second reviewer and consulted her supervisor (MHG) when an additional opinion was needed. The reasons for exclusion were documented and reported in the flow diagram [29] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the source of evidence selection process.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed according to the categories proposed in the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [26] and adapted to the purpose and research questions of the present study: authors, year of publication, country of origin, purpose, population, sample size, context of care, method, type of factor assessed and its description, method of data collection used (scale, questionnaire, interview, etc.), and key findings. Using an Excel table, the first author and a research assistant independently extracted the data after reaching an inter-judge agreement during a pilot testing phase. Discussions took place throughout the extraction process to ensure that no relevant information was missed in case of uncertainty. Although we initially planned on conducting a quality assessment of the included literature, we ultimately decided against it due to the large volume of sources and the primary objective of the review, which was to map and describe the existing body of literature rather than to assess the effectiveness of interventions or make clinical recommendations.

2.5. Data Analysis

The extracted data were coded inductively using Excel software, with codes generated according to the specific factors presented in the literature as associated with perceived coercion. These initial codes were organized in a table to facilitate comparison and synthesis. Following this, broader categories (or themes) were developed by grouping related codes together based on similarities in content or underlying concepts. For example, codes referring to aspects such as age, gender, or education were grouped under a broader category labeled “Sociodemographic”, while codes referring to communication or therapeutic alliance were grouped under “Relational Factors”. The categorization process was iterative and informed by current literature on coercion as well as the research team’s knowledge on the subject of interest. Specifically, we sought to capture how the identified factors related to perceived coercion at different levels (individual, clinical, relational, legal, and structural). Miles et al.’s (2020) content analysis method was followed to structure this process, ensuring that the themes faithfully represented the range of factors as they emerged from the literature [31]. A detailed example of this categorization is provided in Supplementary Table S3. Reviews were considered but excluded from the results if they did not contribute new information, in order to avoid repetition of data. All reviews are presented in Table 2, but only two reviews were included and considered in the results. The preliminary results were presented to the reviewers with lived professional, academic, and personal experiences and discussed through two separate meetings. Their input was considered and incorporated in the final results.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Literature

This scoping review includes 143 publications addressing factors associated with perceived coercion. The included publications are presented in Table 2, organized in chronological order according to their year of publication, to illustrate the evolution of the literature over time.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Authors and Year of Publication | Goal/Objective | Country | Care Context | Population | Sample Size | Design | Factors Evaluated | Scale Used (If Applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rogers (1993) [32] | The present paper is concerned with three questions: (1) To what extent is the nominal label of “voluntary” an indicator of patients entering and remaining in hospital of their own free will? (2) What was the range of perceptions, beliefs, and circumstances surrounding those who had entered the hospital as voluntary patients but felt themselves to be there under duress? (3) What differences of view, if any, exist about treatment and services between those patients who construed their status to be genuinely voluntary compared to those who did not? | UK | Inpatient | Voluntarily admitted patients | 412 | Mixed methods | Legal status | N/A |

| Bennett et al. (1993) [33] | This article presents a qualitative review of the transcripts of a subset of these interviews. It attends specifically to patients’ perceptions of the morality of attempts by others—primarily family members, friends, and mental health professionals—to influence them to be admitted to the hospital, and of the morality of the process by which these influence attempts resulted in admission. | USA | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 70 | Qualitative | Inclusion, beneficent motivation, and good faith | N/A |

| Lidz et al. (1995) [34] | This article looks at the determinants of patients’ perceptions of coercion. | USA | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 157 | Mixed methods | Procedural justice, legal status, and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI) |

| Nicholson et al. (1996) [35] | The present study was therefore conducted with three goals in mind: (1) to provide additional data on the psychometric properties of the Perceived Coercion Scale and the MacArthur Admission Experience survey from which the PCS was derived; (2) to investigate the relationship between formal legal status and patients’ perceptions of the coerciveness of hospitalization; and (3) to examine the relationships between patient characteristics, especially the degree of coercion in hospital admission, and several measures of the efficacy of psychiatric hospitalization. | USA | Inpatient | All patients admitted to WSH between 1 March 1993, and 15 June 1993 | 123 | Mixed methods | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Hiday et al. (1997) [36] | This paper attempts to develop a better understanding of coercion in psychiatric treatment by studying patient perceptions of coercion and of two closely related constructs—patients’ perceptions of negative pressures in the hospital admission process and patients’ perceptions of fair procedures in the attempts to have them hospitalized. It also examines how these constructs are influenced by sociodemographic and clinical factors. | USA | Outpatient | Involuntarily admitted patients who had been court-ordered to outpatient commitment following hospital discharge | 331 | Quantitative | Clinical characteristics and sociodemographic characteristics | The authors used 15 true-false items from the MacArthur Interpersonal Relations Scale to construct three dependent variables: perceived coercion, perceived negative pressures, and perceived procedural inequity |

| Hoge et al. (1997) [37] | In this paper, we report on a study designed to provide preliminary answers to these questions based on patients’ perceptions. (1) How common are “coerced voluntaries” and “uncoerced involuntaries”? (2) When are patients coerced and by whom? Are psychiatrists, other clinicians, or agents of the mental health system pressuring patients? Or are family members and friends responsible for the coercion? (3) How are patients coerced? Are patients being coerced in ways that warrant and are suitable to legal intervention? | USA | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 157 | Mixed methods | Legal status | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI), MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Cascardi et al. (1997) [38] | This study aims to evaluate patients who were court-ordered to undergo involuntary psychiatric evaluation following the expiration of an initial “emergency” detainment. Of particular interest is whether individuals who were allowed to sign themselves into the hospital as voluntary patients experienced the admission process differently from those for whom involuntary treatment petitions were initiated. The study also seeks to assess whether patients’ perceptions of coercion were more strongly influenced by interactions with community members or with hospital staff. | USA | Inpatient | Inpatients court-ordered to Crisis Stabilization Units (CSUs) for involuntary evaluation | 120 | Quantitative | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and locus of control | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI) |

| Lidz (1998) [39] | This commentary will outline both what is currently known and the directions future research on coercion in psychiatric care must take in the coming decade to remain relevant within our evolving mental health system. | USA | N/A | N/A | N/A | Review and commentary of the literature | Relationship with staff | N/A |

| Pescosolido et al. (1998) [40] | The purpose of this study was to systematically consider the different social processes through which people come to enter psychiatric treatment by exploring the stories told by individuals making their first major contact with the mental health system. | USA | Mixed | Inpatients and outpatients making their first major contact with the mental health treatment system | 109 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics and social networks | N/A |

| Lidz et al. (1998) [41] | The purpose of this study was to determine what predicts patients’ perceptions of coercion surrounding admission to a psychiatric hospital. | USA | Inpatient | Psychiatric inpatient at two university-based hospitals, recently admitted | 171 | Mixed methods | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, coercion-related behaviors or events | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI) |

| Hoge et al. (1998) [42] | In the current study, we have included patients, family (including friends and significant others), and clinicians in an attempt to understand two related questions: (1): How do family and clinician perceptions of coercion compare with the Pprceptions of patients? (2): Are the determinants of family and clinician perceptions of coercion the same as the determinants of patient perceptions of coercion? | USA | Inpatient | Data were collected from three groups: newly admitted psychiatric patients, patients’ family members or other significant others who were involved in the admission, and admitting clinicians | 433 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI) |

| Gardner et al. (1999) [43] | The authors examine how patients changed their evaluations of psychiatric hospitalization following hospital treatment. | USA | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 433 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Poulsen (1999) [44] | This study aims to investigate differences in perceived coercion among three groups of psychiatric patients: involuntarily committed, voluntarily admitted but later detained, and purely voluntary patients, and to identify predictors of perceived coercion. | Denmark | Inpatient | Psychiatric patients admitted to five closed psychiatric wards at Aarhus University Hospital | 143 | Quantitative | Legal status, clinical characteristics, social functioning, coercive measures, and sociodemographic characteristics | 5-item version of the Admission Experience Scale (AES), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) |

| McKenna et al. (1999) [45] | This study attempted to determine broad views of the current mental health legislation. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Inpatients in two acute psychiatric inpatient services in Auckland, New Zealand | 138 | Quantitative | Previous admission to a psychiatric hospital, previously committed under mental health legislation, and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Lareau (2000) [46] | This dissertation examines differences between legally mandated and non-legally mandated patients on levels of perceived coercion to enter substance abuse treatment, as well as the effect of the therapeutic alliance on altering intake levels of perceived coercion. | USA | Inpatient | Legally mandated and non-legally mandated patients entering drug treatment at two treatment sites in Philadelphia | 69 | Quantitative | Legal status, therapeutic alliance, and procedural justice | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey—Short Form (AES), The Survey of Treatment Entry Pressures (STEP) |

| Lidz et al. (2000) [47] | This study aims to describe who places pressures on patients to be admitted to psychiatric hospitals and to understand the sources and nature of coercive behaviors in psychiatric admissions. | USA | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals | 433 | Mixed methods | Sources of pressures and types of pressures | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| McKenna et al. (2001) [48] | The purpose of this study was to consider patients’ perceptions of aspects of procedural justice within the context of voluntary and involuntary admission to psychiatric hospitals in New Zealand and determine which aspects may reduce patients’ perceptions of coercion. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Patients admitted to the two acute-admitting psychiatric units of Waitemata Health, Auckland, New Zealand | 138 | Quantitative | Procedural justice | Perceived Coercion Scale within the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Olofsson & Jacobsson (2001) [49] | This study highlights how patients narrated their experiences of being subjected to coercion and their thoughts on how coercion could be prevented in Sweden. | Sweden | Inpatient | Involuntarily admitted patients | 18 | Qualitative | Patients and healthcare professionals narrated their experiences of the same coercive event | N/A |

| Rosen et al. (2001) [50] | In this study, we surveyed patients enrolled in a money management program at a university-affiliated Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) in order to (1) compare the patients’ relationship to their clinicians to their relationship with their money managers and (2) explore the diverse dimensions of clients’ experience of money management. | USA | Outpatient | Outpatients enrolled in the CMHC money management program | 28 | Quantitative | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and therapeutic alliance | N/A |

| Johansson et Lundman (2002) [51] | The study aims to gain a deeper understanding of this experience: patients who are involuntarily admitted to psychiatric care are extremely vulnerable as a consequence of the control from others and of the personal limitations due to a psychiatric disease that can influence their own control of their lives. | Sweden | Inpatient | Involuntarily admitted patients | 5 | Qualitative | Autonomy, perceived coercion, information received, and influence on treatment process | N/A |

| Canvin et al. (2002) [52] | The present paper presents the findings of a qualitative investigation into service users’ perceptions and experiences of living with SDOs (Supervised Discharge Orders). | UK | Outpatient | Patient living with SDOs | 20 | Qualitative | Perceptions and experiences of SDOs and impact on freedom | N/A |

| Watts & Priebe (2002) [53] | Assertive community treatment (ACT) is a widely propagated team approach to community mental health care that “assertively” engages a subgroup of individuals with severe mental illness who continuously disengage from mental health services. ACT condenses a dilemma that is common in psychiatry. ACT proffers social control whilst simultaneously holding therapeutic aspiration. The clients’ perspective of this dilemma was studied in interviews with 12 clients using the “grounded theory” approach. | UK | Outpatient | Assertive community treatment patients in an impoverished inner-city area of London | 12 | Qualitative | Deinstitutionalization challenges and integration and community opposition | N/A |

| Iversen et al. (2002) [54] | In this paper we describe perceived coercion among patients admitted to acute wards in Norway. We applied both the direct and indirect methods to measure perceived coercion. We then compared the two approaches and examined predictors for perceived coercion. | Norway | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients in four acute wards at two Norwegian psychiatric hospitals from October 1998 through November 1999 | 223 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, length of stay, and global assessment of functioning | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES), Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| McKenna et al. (2003) [55] | The study aimed to explore the impact of coercion on admissions to forensic psychiatric hospitals and to test the hypothesis that admission to forensic psychiatric hospitals would be associated with significantly greater perceived coercion than that perceived by involuntary admissions to general psychiatric hospitals. A further goal was to determine which aspects of procedural justice might reduce patients’ perceptions of coercion on admission to a forensic psychiatric hospital. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Patients admitted to forensic psychiatric hospitals and involuntary admissions to general psychiatric hospitals in New Zealand | 138 | Quantitative | Negative pressures, procedural justice, and emotional responses to the admission process | Perceived Coercion Scale within the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Elbogen et al. (2003) [56] | The study aimed to address these questions concerning multiple forms of leverage in treatment and to take preliminary steps toward exploring the combined effects of outpatient commitment (OPC) and representative payees on perceived coercion and treatment adherence. | USA | Outpatient | Patients who had been involuntarily admitted to 1 of 4 hospitals and who were awaiting discharge on outpatient commitment to 1 of 9 counties in north-central North Carolina | 258 | Quantitative | Outpatient commitment | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Swanson et al. (2003) [57] | No study to date has directly examined whether legally mandated treatment in the community significantly affects quality of life one way or the other. This paper addresses that question empirically. | USA | Outpatient | Involuntarily hospitalized patients who had been ordered to undergo a period of OPC (involuntary outpatient commitment) upon discharge | 262 | Quantitative | Patients were randomly assigned to be released or continue under outpatient commitment in the community after hospital discharge and were followed for one year. Quality of life, treatment characteristics, and clinical outcomes | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Sørgaard (2004) [58] | This article presents the results of an intervention study aimed at reducing the level of patient-perceived coercion in two acute wards at a psychiatric hospital in Northern Norway. The interventions consisted of procedures aimed at including the patients in the processes of formulating their treatment plan and in a continuous evaluation of their stay. | Norway | Inpatient | Inpatients in an acute psychiatric ward | 190 | Quantitative | Coercive measures and patronizing attitudes and behaviors | Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Taborda et al. (2004) [59] | The main objective of the present study was the assessment of perceptions of coercion among psychiatric and nonpsychiatric (surgical and medical) patients after admission. | Brazil | Inpatient | Comparison between psychiatric patients and medical/surgical patients | 205 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Bonsack (2005) [60] | The study aimed to assess the subjective perception of psychiatric admission by patients while still in hospital. | Switzerland | Inpatient | Patient admitted to adult psychiatric care | 87 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | N/A |

| Van Dorn et al. (2005) [61] | Specifically, the current paper explores the following four interrelated questions: (1) Do persons with serious mental illness think leveraged treatment is fair and effective? (2) What are the characteristics of persons who think that leveraged treatment is fair or unfair, effective or not effective? (3) How are fairness and effectiveness related? (4) How do perceived barriers to care relate to the perceived fairness of leveraged treatment? | USA | Outpatient | Outpatients from publicly funded mental health treatment programs | 1011 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, social environment, clinical, and psychological and behavioral profile | N/A |

| Rose et al. (2005) [62] | Review of the literature. This study aimed to review patients’ views on issues of information, consent, and perceived coercion about electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). | UK | Inpatient | Patients given ECT | 17 | Review of the literature | Perceived coercion information received about ECT | N/A |

| Larsson-Kronberg et al. (2005) [63] | The study aimed to explore the experiences of coercion among individuals undergoing assessment and treatment for substance use disorders under Swedish legislation (LVM) and to understand their perspectives on the entire process from assessment to aftercare. | Sweden | Mixed | Individuals undergoing assessment or with previous experience of assessment and involuntary care under the Swedish Care of Addicts in Certain Cases Act (LVM) | 74 | Quantitative | Contact with healthcare professionals, opportunities to express opinions, emotional reactions to coercive measures, substance use patterns, and treatment satisfaction | Uppsala questionnaire on coercive measures |

| Bindman et al. (2005) [64] | This study aimed to investigate predictors of perceived coercion in subjects admitted to psychiatric hospitals in the UK and to test the hypothesis that high perceived coercion at admission predicts poor engagement with community follow-up. | UK | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals | 100 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, previous contact with services, and objectively coercive aspects of the admission | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| McKenna et al. (2006) [65] | The aim of this study is to determine the level of coercion perceived by those under outpatient commitment in New Zealand. Emphasis is given to consideration of the presence of ambivalence and the role of processes of interaction, including procedural justice, in relation to patients’ perceptions of coercion. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Involuntary outpatient within the first year of their community treatment order presenting for their statutory clinical review | 138 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, previous contact with services, and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Swartz et al. (2006) [66] | This study examined lifetime use rates and correlates of outpatient commitment or related civil court–ordered outpatient treatment in five U.S. communities. | USA | Outpatient | Outpatients from five outpatient clinics affiliated with community mental health centers located in Chicago; Durham, North Carolina; San Francisco; Tampa; and Worcester, Massachusetts | 1011 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, treatment compliance, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, previous contact with services, and treatment satisfaction | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Kjellin et al. (2006) [67] | The objectives of this article are to compare levels of perceived coercion among committed and voluntary patients at admission to psychiatric inpatient care across the five Nordic countries and across centers within countries and to analyze differences in perceived coercion in terms of legal prerequisites and differences in clinical practice. | Switzerland | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients from twelve psychiatric hospitals | 920 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, and previous contact with services | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Appelbaum & Redlich (2006) [68] | This study explores aspects of the population subject to financial leverage, including modeling the predictors of leverage and examining the relationships among financial leverage, treatment compliance, and attitudes toward both treatment and the use of leverage. The goal is to better inform discussions about the legitimate extent of leverage on persons with mental disabilities and the procedures that should regulate these practices. | USA | Outpatient | Outpatients from publicly funded programs were sampled from each of five sites: Chicago, Illinois; Durham, North Carolina; San Francisco, California; Tampa, Florida; and Worcester, Massachusetts | 200 | Quantitative | Treatment compliance, financial leverage, and treatment satisfaction | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| McKenna et al. (2006) [65] | This thorough literature search on “coercion” and “civil commitment” aimed to outline best practice management strategies for nurses during the clinical application of civil commitment of mentally ill persons. | New Zealand | Mixed | Patients admitted to acute mental health services, acute forensic mental health services, and community mental health services in New Zealand | N/A | Review of the literature | Degree of restriction associated with the service involved, pattern of communication, and procedural justice | N/A |

| Castille et al. (2007) [69] | understand why, given the objective difference in the use of coercion, there was no difference in the subjective perception of coercion. | USA | Outpatient | patients discharge from psychiatric hospital on court order or not | 20 | Mixed methods | Court order vs. no court order after hospital discharge relationship with case manager | Not specified |

| Katsakou & Priebe (2007) [70] | This study aimed to explore psychiatric patients’ experiences of involuntary admission and treatment by reviewing qualitative studies. | UK | Inpatient | Involuntarily admitted patients in acute general psychiatric wards | 5 | Review of qualitative studies | Autonomy, quality of care, and emotional impact of involuntary treatment | N/A |

| Renberg et al. (2007) [71] | This study aimed to investigate determinants for perceived coercion during the admission process among voluntarily and involuntarily admitted psychiatric patients, with special focus on sex-specific patterns. | Sweden | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted psychiatric patients | 282 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Sørgaard (2007) [72] | The purpose of this article is to analyze the differences in experienced coercion, patient involvement, and user satisfaction in three groups of patients: voluntary admitted, committed, and a group where the admission was a result of joint decisions between themselves and others. | Norway | Inpatient | Patients in three closed acute wards at the psychiatric department of Nordland Hospital located in the city of Bodø in rural Northern Norway | 189 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, autonomy, clinical characteristics, coercive measures, previous contact with services, and treatment satisfaction | Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Davidson & Campbell (2007) [73] | This paper begins by exploring the literature on coercion and mental health practice and, in doing so, highlights arguments about the relative effectiveness of strategies and ethical dilemmas that are prevalent in this field. The paper concludes with recommendations to develop ways in which practitioners might be better prepared to work within the context of coercive policy and law. | Ireland | Inpatient | The groups consisted of the clients and their respective keyworkers: an Assertive Outreach (AO) group and a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) group | 157 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Zervakis et al. (2007) [74] | This paper examines the association between past involuntary commitment and current perceptions of coercion in a sample of 205 voluntarily hospitalized veterans with severe mental illness. | USA | Inpatient | Voluntarily hospitalized veterans with severe mental illness | 205 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, legal status, treatment history, coercive measures, alcohol and drug use, insight into illness severity, self-rated health, and social support | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Link et al. (2008) [75] | This study aimed to address the divergent claims of the coercion to beneficial treatment perspective and the coercion to stigma perspective using a longitudinal study of outpatient commitment among individuals with severe mental illnesses. | USA | Outpatient | Individuals between the ages of 18 and 65, ascertained in treatment facilities in the Bronx and Queens, New York City | 184 | Quantitative | Previous involuntary inpatient hospitalizations, assignment to mandated outpatient treatment (AOT), and perceptions of being coerced into treatment | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Johansson et al. (2009) [76] | This study elucidates the meaning care has to patients on a locked acute psychiatric ward. | Sweden | Inpatient | Patients admitted voluntarily or involuntarily to the psychiatric department of a general hospital in Western Sweden | 10 | Qualitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, legal status, and previous contact with services | N/A |

| Stanhope et al. (2009) [77] | This exploratory study examined the extent to which social interaction between consumers and their case managers is related to the treatment experience from the perspective of consumers. The study addressed the following questions: (1) What factors are associated with perceived coercion by the consumer? (2) To what extent are perceived coercion, the consumer-provider relationship, and consumer and service contact characteristics associated with consumers’ evaluation of a service contact? | USA | Outpatient | Consumers of the Housing First program | 80 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, housing status, and service contact characteristics | N/A |

| Bennewith et al. (2010) [78] | This study aimed to assess whether adult Black and minority ethnic (BME) patients detained for involuntary psychiatric treatment experienced more coercion than similar White patients. | UK | Inpatient | Patients who had been admitted under Sections 2, 3, or 4 of the Mental Health Act 1983 in the UK or who became involuntary patients within a week of admission | 778 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and ethnicity | Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Kim et al. (2010) [79] | This study aimed to investigate variables that influence psychiatric patients’ experience of coercion and the effects of the coercion on the therapeutic relationship. | South Korea | Inpatient | Psychiatric patient | 279 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, procedural justice, and coercive measures | N/A |

| Fu et al. (2010) [80] | Admission experience has been shown to be related to insight and treatment adherence. This study evaluates the clinical correlates of the Chinese Admission Experience Survey (C-AES). | Hong Kong | Inpatient | Inpatients with schizophrenia | 40 | Quantitative | Clinical characteristics and treatment compliance | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (Chinese version) |

| Phelan et al. (2010) [81] | This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and outcomes of New York State’s outpatient commitment program, focusing on psychiatric outcomes, quality of life, perceived coercion, and stigma. | USA | Outpatient | Individuals recently mandated to outpatient commitment and individuals recently discharged from psychiatric hospitals | 184 | Quantitative | History of involuntary commitment and number of involuntary hospitalizations | N/A |

| Latimer et al. (2010) [82] | This study tested the hypotheses that negative, but not positive, pressures would be associated with higher perceived coercion, and that procedural justice (which we relabeled “client-centredness” for reasons described below) would be associated with lower perceived coercion. Finally, it assessed whether clinical variables were correlated with negative pressures, with client-centeredness, and with perceived coercion. | Canada | Outpatient | Assertive community treatment patients | 38 | Quantitative | Procedural justice, negative pressures, and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Interview (AEI) |

| Thøgersen et al. (2010) [83] | This study aimed to explore views on—and perceptions of—coercion of patients in Danish assertive community teams. | Denmark | Outpatient | Assertive community treatment patients | 6 | Qualitative | Influence on treatment process, autonomy, and privacy | N/A |

| Patel et al. (2010) [84] | In this study, we investigated patients’ perspectives of coercion for both depot and oral antipsychotic treatment using a quantitative instrument. For the purposes of this study, “coercion” was defined as that perceived by the patient and did not refer to legal detention status. The null hypothesis was that reported levels of coercion would not differ according to current antipsychotic formulation (depot versus oral tablets). | UK | Outpatient | Voluntary outpatients on maintenance medication | 72 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Jaeger & Rossler (2010) [85] | This study aimed at investigating the factors influencing psychiatric patients’ subjective measures of perceived coercion, fairness, and effectiveness. We hypothesized that patients with experience of leverage and/or coerced voluntarism were more likely to perceive coercion and would feel they were treated with less fairness and would in consequence evaluate their treatment as less effective. An additional aim was to investigate the influence of insight into illness and socio-demographic and clinical factors on these subjective measures. | Switzerland | Mixed | Inpatients and outpatients at the Department of General and Social Psychiatry, University of Zurich | 187 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, and treatment compliance | Modified version of the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Howard (2010) [86] | This study aimed to examine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of women’s crisis houses by first examining the feasibility of a pilot patient-preference randomized controlled trial (PP–RCT) design. | UK | Mixed | Women requiring voluntary admission who could be admitted to a psychiatric inpatient ward or women’s crisis house | 103 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, quality of life, and satisfaction with care | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Daffern et al. (2010) [87] | The aim of the current study is to examine perceptions of coercion and interpersonal style in patients with personality disorder and to examine the relationship between these and subsequent aggression and self-harm during hospitalization. More specifically, do patients with particular interpersonal styles (i.e., hostile and dominant) experience greater coercion, and does this result in them being more likely to act out their frustrations with aggression and self-harm? | Australia | Inpatient | Patients detained under the Mental Health Act (1983) with a legal classification of psychopathic disorder, treated in the Personality Disorder Service at Rampton Hospital | 39 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Galon & Wineman (2010) [88] | The primary purpose of this article is to review current information and research related to coercion and the associated concept of procedural justice in mental health treatment and to discuss the implications of this knowledge for nursing practice. A secondary purpose is to spur thought and comment within the psychiatric nursing community on forms of coercive treatment, particularly OPC. | USA | Outpatient | N/A | N/A | Review and discussion of the literature | Procedural justice, outpatient commitment, and coercive measures | N/A |

| Newton-Howes et al. (2011) [20] | This study systematically examined the empirical literature on the themes and correlates of coercion as defined by the subjective experience of patients in psychiatric care. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Articles reported on patients in secondary psychiatric care whose treatment was being managed by a consultant psychiatrist | 27 | Systematic review | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, quality of life, and influence on treatment process | N/A |

| Katsakou et al. (2011) [89] | The present study aimed (a) to investigate whether specific sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are associated with perceptions of coercion at admission among legally voluntary patients, (b) to examine whether voluntary patients who feel coerced into admission continue to feel coerced during hospital treatment, (c) to identify factors associated with feelings of coercion during treatment, and (d) to explore what experiences—in the view of the patients—lead to feelings of coercion both at admission and during treatment. | UK | Inpatient | Voluntarily admitted patients in nine acute wards in two hospitals in East London | 270 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, and satisfaction with care | McArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Tschopp et al. (2011) [90] | The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the degree of coercion perceived by mental health consumers in an (Assertive Community Treatment) ACT program, the extent to which coercive strategies are perceived to be implemented, and how perceived coercion might relate to the variables of quality of life, working alliance, and sense of empowerment. | USA | Outpatient | Adults diagnosed with predominantly schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders in an ACT program in the Midwest of the USA | 65 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics and legal status | N/A |

| Castille et al. (2011) [91] | In the present chapter we begin with a comparison between the two previously mentioned approaches to measuring coercion. We ask: does a person with a court order perceive him/herself as being more coerced than a person in outpatient treatment without a court order? | USA | Outpatient | Men and women between the ages of 18 and 65 years with a history of serious mental illness from various outpatient clinics in two boroughs of New York City | 184 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, quality of life, legal status, and previous contact with services | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Sheehan & Burns (2011) [15] | The aim of the study was to investigate the association between the therapeutic relationship and perceived coercion in psychiatric admissions. | UK | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospital | 164 | Quantitative | Therapeutic alliance, sociodemographic characteristics, and legal status | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Galon & Wineman (2011) [92] | This study aimed to compare OPC and ACT as forms of coercive interventions to evaluate the influence of each individually and in combination on treatment compliance and client-centered outcomes, including quality of life, symptom distress, empowerment, violence, and victimization. | USA | Outpatient | Individuals with severe and persistent mental health problems | 154 | Quantitative | Outpatient commitment and assertive community treatment | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Zuberi et al. (2011) [93] | This article explores perceptions of coercion and hospitalization among patients admitted to a psychiatric unit in Karachi. We looked for associated patient characteristics. | Pakistan | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospital | 87 | Quantitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Newton-Howes & Stanley (2012) [5] | The aim of this review is therefore to systematically collate those papers that outline the prevalence of perceived coercion to ascertain how common this is and understand the variation in reported rates. An exploration of the factors that may increase or decrease these rates from both a methodological and an epidemiological perspective is also considered. | New Zealand | Mixed | Papers describing adults between 16 and 65 years of age in adult psychiatric care | 18 | Literature review and meta-regression | Legal status, geographical study location, and instruments used to measure coercion | N/A |

| Theoridou et al. (2012) [14] | The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between perceived coercion and the therapeutic relationship. We hypothesized that perceived coercion would negatively influence the therapeutic relationship as rated by the patient, and vice versa. Thus, we did not posit a unidirectional but a reciprocal effect. We further hypothesized perceived coercion to be influenced by legal status, both at admission and in previous hospitalizations. | Switzerland | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals | 116 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, and legal status | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Del Vecchio et al. (2012) [94] | This study, conducted within the EUNOMIA project on the evaluation of coercive measures in psychiatry in twelve European countries, intended to assess (1) the clinical and socio-demographic characteristics most frequently associated with higher levels of perceived coercion at admission (2) the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and levels of perceived coercion. | Italy | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric wards in twelve European countries (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) | 2815 | Quantitative | Clinical characteristics, and social functioning | McArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Galon et al. (2012) [95] | This study aimed to examine if assignment to OPC status or ACT differed by race and to elucidate the effect of race on the perceptions of procedural justice and coercion in persons subject to OPC. | USA | Outpatient | Patients placed under outpatient commitment (OPC) orders | 140 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, and procedural justice | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Fiorillo et al. (2012) [96] | This study aimed to identify (1) sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with perceived coercion at admission and (2) changes in symptoms and global functioning associated with changes in perceived coercion over time. | Italy | Inpatient | Patients who were involuntarily admitted or who felt coerced into hospital treatment despite a legally voluntary admission | 3093 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, global assessment of functioning, legal status, and previous contact with services | McArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), Cantril Ladder of Perceived Coercion |

| Morcos (2012) [97] | This paper aimed to examine the relationship between interpersonal style, attitude to medication and potential adherence, and perceived coercion. | UK | Inpatient | Adult male inpatients from general and forensic psychiatry wards treated with antipsychotic medication | 52 | Quantitative | Interpersonal style and treatment compliance | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Jaeger et al. (2013) [98] | This paper aimed to examine the long-term influence of involuntary hospitalization on medication adherence, engagement in outpatient treatment and perceived coercion to treatment participation. | Germany | Inpatient | Hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 374 | Quantitative | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics | Compliance Self-Rating Instrument (CSRI-K) |

| Anestis et al. (2013) [99] | This study aims to elucidate the characteristics of patients and their admissions that increase the likelihood of perceived coercion during short-term psychiatric hospitalization. It seeks to determine whether interpersonal style—specifically Hostile (H), Dominant (D), and Hostile–Dominant (H–D) styles, which have previously been associated with adverse reactions to hospitalization—along with psychiatric symptoms, gender, and admission status (voluntary or involuntary), predict perceived coercion. Additionally, the study investigates whether the perception of coercion at admission remains stable one year after hospitalization. | Australia | Inpatient | Inpatients admitted to the two acute units at the Alfred Hospital Inpatient Psychiatry Department, in Melbourne, Australia, between 1 March 2009 and 10 August 2009 | 125 | Mixed methods | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| McNiel et al. (2013) [100] | The study aimed to evaluate the hypothesis that aspects of the treatment relationship, such as the working alliance, psychological reactance, and perceived coercion, could be important in understanding treatment adherence and satisfaction in a group of patients at risk of experiencing leverage. | USA | Outpatient | Outpatients at two community mental health centers | 198 | Quantitative | Working alliance quality, psychological reactance, leverage, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), adapted for outpatient treatment |

| Seo et al. (2013) [101] | This study analyzed whether coercive intervention observed in Korea’s field of mental health could be justified by the basic assumptions of paternalists: the assumptions of incompetence, dangerousness, and impairment. | South Korea | Inpatient | Patients who had been hospitalized following diagnoses of schizophrenia or mood disorders stayed in the hospital for four weeks | 248 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and global assessment of functioning | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Terkelsen & Larsen (2013 [102]) | This study aimed to explore how patients and staff act in the context of involuntary commitment, how interactions are described, and how they might be interpreted. | Norway | Inpatient | People with mental health and substance abuse problems | 38 | Qualitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and characteristics of the therapeutic environment | N/A |

| Newton-Howes et al. (2014) [103] | This study aimed to investigate the experience of community treatment orders (CTOs) among Maori and non-Maori patients, comparing their views within mainstream and Maori mental health services. | New Zealand | Outpatient | Patients with experience of CTOs | 79 | Quantitative | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and type of mental health service | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Larsen & Terkelsen (2014) [104] | This brief literature review gives a few examples of differences in staff and patient attitudes related to coercion, shows how forced treatment might weaken the alliance between staff and patients, and suggests dialogue and reciprocity as practices to reduce coercion. | Norway | Inpatient | Patients from an inpatient psychiatric unit in Norway | 12 | Qualitative | Legal status and sociodemographic characteristics | N/A |

| O’Donoghue et al. (2014) [105] | In this study we aimed to quantify the proportion of voluntarily admitted service users with levels of perceived coercion equivalent to that of involuntarily admitted service users. Secondly, we aimed to identify demographic and clinical characteristics of voluntarily admitted service users who experienced high levels of perceived coercion. | Ireland | Inpatient | Individuals admitted voluntarily and involuntarily to three psychiatric hospitals | 161 | Quantitative | Legal status, clinical characteristics, negative pressures, and procedural justice | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Riley et al. (2014) [106] | The objective of this qualitative study was to explore (1) patients’ experiences with OC (outpatient commitment) and (2) how routines in care and health services affect patients’ everyday living. | Norway | Outpatient | Patients under an OC order who had been at least under the order for 3 months and lived in the catchment area | 11 | Qualitative | Accommodation (staffing, supervision, etc.), frequency of monitoring by clinicians, initial contact with mental health services, and clinical characteristics | N/A |

| Munetz et al. (2014) [107] | The study aimed to examine levels of perceived coercion, procedural justice, and the impact of mental health court (MHC) and assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) programs among participants in a community treatment system. | USA | Outpatient | Individuals who had graduated from a mental health court program and former AOT participants who were no longer under court supervision | 52 | Quantitative | Interactions with judges and case managers and procedural justice | Modified MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS) |

| Prebble et al. (2015) [21] | This review aimed to identify literature pertaining to the experiences of people admitted voluntarily to acute adult mental health facilities. | New Zealand | Inpatient | Publications focused on the experiences of voluntary service users in acute adult psychiatric facilities | 46 | Review of the literature | Legal status, perception of coercion, procedural justice, knowledge of rights, and informed consent | N/A |

| Donskoy (2015) [108] | The purpose of this paper is to present a focused viewpoint of coercion in psychiatry from the perspective of a survivor and activist. | UK | Inpatient | Psychiatric inpatients | N/A | Viewpoint of a psychiatric survivor and human rights activist | Lack of capacity, consent, paternalism, complicit psychiatry, and application of human rights standards | N/A |

| Canvin (2016) [109] | This chapter presents a synthesis of major research themes and findings on patients’ subjective experiences and perceptions of coercion in community psychiatry. | Unspecified | Outpatient | Patients in community psychiatric settings | N/A | Book chapter: synthesis of the literature | Interventions (medication, appointments); obligations (institutional rules, treatment plans, providers’ expectations); threats; and safety | N/A |

| Norvoll & Pedersen (2016) [110] | This study aimed to explore the views of people with mental health problems on the concept of coercion and to argue for a broader socio-ethical perspective on coercion in mental health care. | Norway | Mixed | Adults with various mental health problems and experiences with coercion | 24 | Qualitative | Formal and informal coercion across health and welfare services, power relations, deprivation of freedom, and social and existential impacts of coercion | N/A |

| Fugger et al. (2016) [111] | The objective of the present longitudinal investigation was to analyze the burden caused by physical restraint in psychiatric wards. Three specific research questions were addressed: (1) Does the patients’ subjective perception of physical restraint change the longer the time span from the last fixation? (2) Is there a difference between the patients’ and the investigators’ evaluation of physical restraint? (3) Is there a connection between physical restraint and the presence of consecutive posttraumatic stress disorder? | Austria | Inpatient | Patients who were involuntarily admitted and physically restrained at a psychiatric intensive care unit in the general hospital of Vienna (AKH) | 47 | Quantitative | Influence on the treatment process, self-evaluation of physical restraint, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, clinical characteristics, and clinical global impression | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Francombe Pridham et al. (2016) [22] | This review of literature aimed to examine the relationship between community treatment orders (CTOs) and patients’ perceptions of coercion, with the objective of understanding factors that might influence the experience of being placed under a CTO. | Canada | Outpatient | Publications focused on the experiences of patients who were or had been subject to a community treatment order (CTO) | 23 | Review of the literature | Clinical history and characteristics, procedural justice, the legal and health services context of CTOs, presence of additional forms of leverage, and communication with service providers | N/A |

| Raveesh et al. (2016) [112] | This study aimed to assess perceived coercion in persons with mental disorders admitted involuntarily and correlate it with sociodemographic factors and illness variables. | India | Inpatient | Patients admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric hospital | 301 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and coercive measures | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Zlodre et al. (2016) [113] | The current study examined competence and coercion in a cohort of individuals with severe personality disorder who were detained in high-security hospital and prison settings. | UK | Inpatient | Individuals with severe personality disorder who were detained in high-security hospital and prison settings | 174 | Quantitative | Clinical characteristics, competence to consent to treatment, and coercion | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Abt (2016) [114] | The research question guiding this dissertation is to explore patients’ reactions to coercion. How does it influence their behavior in the relationship they have with healthcare providers? Specifically, the aim is to understand how the patient processes their experience of coercion and how they manage it. | Switzerland | Inpatient | Involuntarily admitted patients | 11 | Qualitative | Patients’ experiences of involuntary hospitalization and therapeutic alliance | N/A |

| Opsal et al. (2016) [115] | The present study aimed to investigate the role that perceived coercion played among patients with SUD that entered treatment. We also aimed to clarify whether patients that were admitted involuntarily perceived coercion differently from those that were admitted voluntarily and to identify factors that could predict perceived coercion. | Norway | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 192 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and legal status | Perceived Coercion Questionnaire (PCQ) |

| Gowda et al. (2016) [116] | The main questions of this study were (1) which coercive measures were taken? (2) What was the perceived coercion at admission and at discharge? (3) Which patient and contextual characteristics were related to perceived coercion at admission and discharge? | India | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals | 75 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and clinical global impression | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Gowda et al. (2017) [117] | We aimed to study coercion experiences among patients with schizophrenia who were admitted involuntarily. Additionally, we also assessed if demographic factors, clinical factors, and the use of coercive measures had any influence on how patients perceived the necessity of their own involuntary admission. | India | Inpatient | Patients with schizophrenia admitted under special circumstances of the Mental Health Act | 76 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| O’Donoghue et al. (2017) [10] | The ‘Service Users’ Perspective of their Admission’ study examined voluntarily and involuntarily admitted service users’ perception of coercion during the admission process and whether this was associated with factors such as the therapeutic alliance, satisfaction with services, functioning, and quality of life. This report aims to collate the findings of the study. | Australia | Inpatient | Involuntarily admitted patient to three psychiatric inpatient units in Dublin and Wicklow | 161 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Larkin & Hutton (2017) [23] | This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the direction, magnitude, and reliability of the relationship between capacity in psychosis and a range of clinical, demographic, and treatment-related factors, thus providing a thorough synthesis of current knowledge. | UK | Unspecified | Publications focused on adults diagnosed with a non-affective psychotic disorder | 23 | Systematic review, meta-analytical and narrative synthesis | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and perceived coercion | N/A |

| Anonymous (2017) [118] | This article presents a patient’s experience with psychiatric services. | Lebanon | Mixed | Psychiatric service user | N/A | First-person account | Legal status and relationship with staff | N/A |

| Kisely et al. (2017) [119] | This systematic review aims to examine the effectiveness of compulsory community treatment (CCT) for people with severe mental illness (SMI). | Australia | Outpatient | Trials of adults with SMIs who were managed in a community setting | 3 | Systematic review | Comparison I: compulsory community treatment versus entirely voluntary care; comparison II: community treatment orders versus supervised discharge; comparison III: community treatment orders versus standard care | N/A |

| Ramachandra et al. (2017) [120] | The present study was aimed at investigating the perceived coercion of psychiatric patients during admission into a psychiatric hospital, keeping the current Mental Health Act 1987 and MHC Bill, 2013, in perspective. | India | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 205 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, legal status, and history of past hospitalization | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) |

| Bradbury et al. (2017) [121] | The aim of the current study was to provide an understanding of the lived experience of involuntary transport (under the MHA) from the perspectives of consumers, carers, mental health nurses, police officers, and ambulance paramedics. | Australia | Inpatient | People with the lived experience of involuntary transport under the MHA: consumers, carers, mental health nurses, police officers, and ambulance paramedics | 16 | Qualitative | Perspectives of consumers, carers, mental health nurses, police officers, and ambulance paramedics | N/A |

| Tomlin et al. (2018) [122] | This systematic review examines both empirical and policy literature with the aim of conceptualizing the restrictiveness of forensic care as described by residents, staff, and academic commentators. | UK | Inpatient | Papers were included if they were conducted in secure forensic facilities and involved mentally disordered offenders aged over 18 with any clinical diagnosis | 50 | Systematic review and concept analysis | Phenomenon of restrictiveness as experienced through relationships, institutional characteristics, and systemic factors | N/A |

| Horvath et al. (2018) [123] | The present study examines forensic psychiatric inpatients’ perception of coercion regarding the prescribed antipsychotic medication and factors associated with the perception of coercion. | Germany | Inpatient | Patients with schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders in two forensic psychiatric institutions in Southern Germany | 56 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES), Coercion Ladder (CL), Coercion Experience Scale (CES) |

| Nakhost et al. (2018) [24] | This study aimed to assess the perception of coercion among service users treated under a community treatment order (CTO) compared to a matched comparison group of voluntary psychiatric outpatients and examined the potential predictors of perceived coercion. | Canada | Outpatient | Service users treated under a CTO; voluntary psychiatric outpatients | 138 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, legal status, procedural justice, and perceived coercion | N/A |

| Gowda et al. (2018) [124] | This article aimed to study the prevalence of restraint in an Indian psychiatric inpatient unit and to examine the level of perceived coercion correlating to various forms of restraint. | India | Inpatient | Psychiatric inpatients | 200 | Qualitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, legal status, history of past hospitalization, and coercive measures | N/A |

| Allison & Flemming (2019) [125] | The aim of this review was to explore mental health patients’ treatment-related experiences of softer coercion and its effect on their interactions with practitioners through a synthesis of qualitative research. There are two main objectives (1) identify patients’ experiences of soft/subtle coercion during admission to, or in, treatment in mental health services and (2) explore the perceived effect of this coercion on patient–practitioner interactions. | UK | Inpatient | Papers describing experiences of patients in mental health services | 11 | Qualitative thematic synthesis | Sense of self, therapeutic alliance and patients’ perception about their transition through treatment | N/A |

| Sampogna et al. (2019) [13] | The aim of the study was to (1) identify the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with high levels of perceived coercion at admission in psychiatric wards; (2) assess the relationship between the levels of perceived coercion at admission and the levels of satisfaction with received care after three months of hospitalization in a sample of Italian patients with severe mental disorders. | Italy | Inpatient | Patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals | 294 | Quantitative | Legal status, sociodemographic characteristics, and satisfaction with care | MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale (MPCS), Cantril Ladder of Perceived Coercion Scale |

| Lamothe et al. (2019) [126] | The primary objective was to measure the relationship between coercive stress experienced by patients hospitalized in the psychiatric intensive care unit and their level of insight in order to identify potential psychotherapeutic approaches to improve their experience of care and, consequently, enhance clinical practice. The secondary objective was to highlight a potential link between specific coercive measures (such as seclusion) and coercive stress. | France | Inpatient | Patients who had been hospitalized in the psychiatric intensive care unit of the Caen University Hospital | 40 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | Coercion Experience Scale (CES) |

| Guzmán-Parra et al. (2019) [127] | The objective of this study was to analyze the patients’ perceived coercion, symptoms of post-traumatic stress, and subjective satisfaction with the hospitalization treatment associated with the use of different coercive measures during psychiatric hospital stays, particularly the use of involuntary medication, mechanical restraint, or a combination of these measures. | Spain | Inpatient | Patients who had been subject to coercive measures during their psychiatric hospitalization in the Mental Health Hospitalization Units of the University Regional Hospital of Malaga and the General Hospital of Jerez de la Frontera | 111 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, coercive measures, satisfaction with treatment, post-traumatic stress, and perceived stress | Coercion Experience Scale (CES), Coercion Ladder (CL) |

| Akther et al. (2019) [128] | The aim of this systematic review was to synthesize qualitative evidence of patients’ experiences of being formally assessed for admission and/or the subsequent experience of being detained under mental health legislation. This included any legal processes that take place during the assessment process and during detention, such as mental health tribunals. | UK | Inpatient | Papers describing patients’ experiences of assessment or detention under mental health legislation | 56 | Systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis | Information and involvement in care, therapeutic environment, relationships with staff, and impact of detention on self-worth and emotional well-being | N/A |

| Golay et al. (2019) [129] | The first objective of this study was to disentangle the respective contributions of legal admission status and perceived admission status in predicting perceived coercion. The second objective was to examine the extent to which the perceived usefulness of hospitalization influenced perceived coercion. | Switzerland | Inpatient | Patients hospitalized in the Department of Psychiatry at Lausanne University Hospital | 152 | Mixed methods | Perceived legal status, perceived need for hospitalization, and subjective improvement | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES), Coercion Experience Scale (CES) |

| Gerle et al. (2019) [130] | The aim of this study was to investigate how 6 patients, who had received care for self-injurious behavior, perceived coercion and how they think coercion could be avoided. | Sweden | Inpatient | Patients who had engaged in self-injury and had been subjected to coercive measures during treatment | 6 | Qualitative | Threats, coercive measures, control, and involvement in care | N/A |

| Mandarelli et al. (2019) [131] | The aim of the present study was to translate into Italian and validate the Admission Experience Survey (I-AES) and to explore its psychometric properties, including factorial structure. A second objective of the study was to investigate differences in perceived coercion in different diagnostic groups of psychiatric patients as well as in voluntarily and involuntarily hospitalized patients. | Italy | Inpatient | Voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients | 156 | Quantitative | Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics | MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (Italian version) |

| Clément et al. (2020) [132] | The objective of this study is to identify differences in perceptions between nurses and patients regarding their ideal relationship in the context of a first psychotic episode. | Canada | Inpatient | Individuals who experienced involuntary hospitalization in the context of a first psychotic episode; nurses | 10 | Qualitative | Therapeutic alliance | N/A |

| Jessell (2020) [133] | This dissertation aimed to understand the relationship between recovery orientation and the role of psychiatric medication in service planning. | USA | Mixed | Users of mental health services | 731 | Mixed methods | Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, recovery orientation of the plan, and role of psychiatric medication | N/A |