Barriers in Access to Healthcare Services in Greece Post-COVID-19: Persisting Challenges for Health Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographics

3.2. Healthcare Use

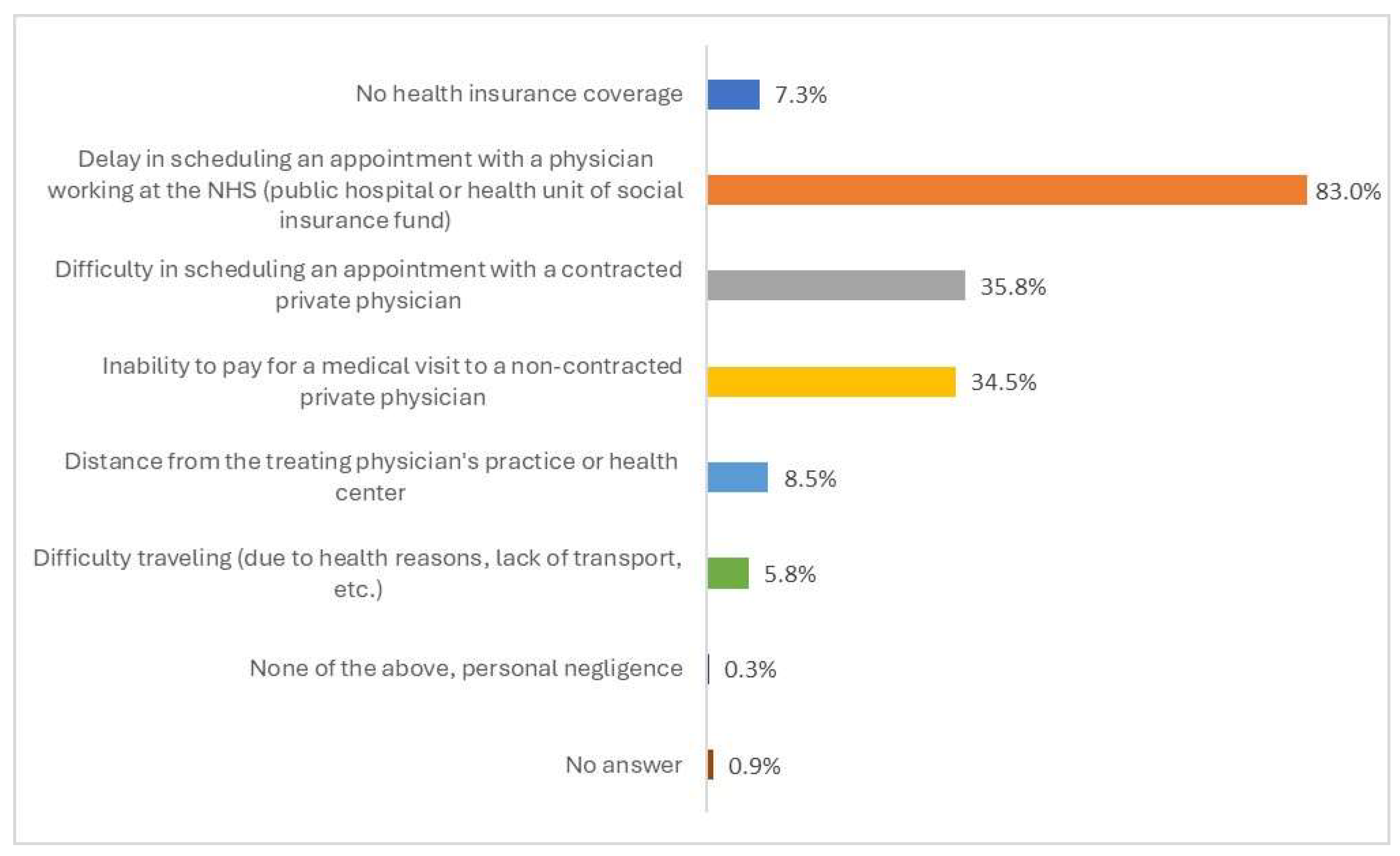

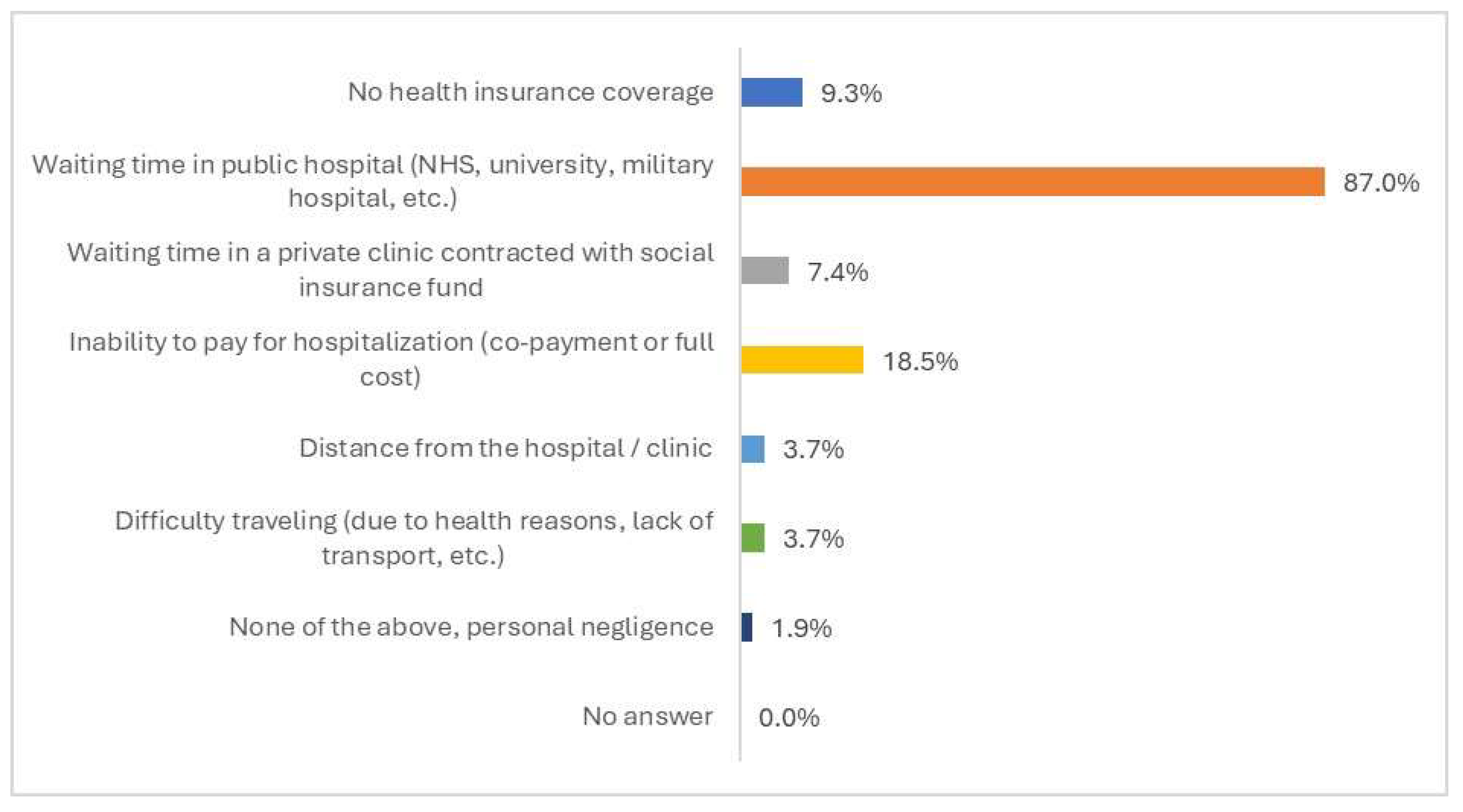

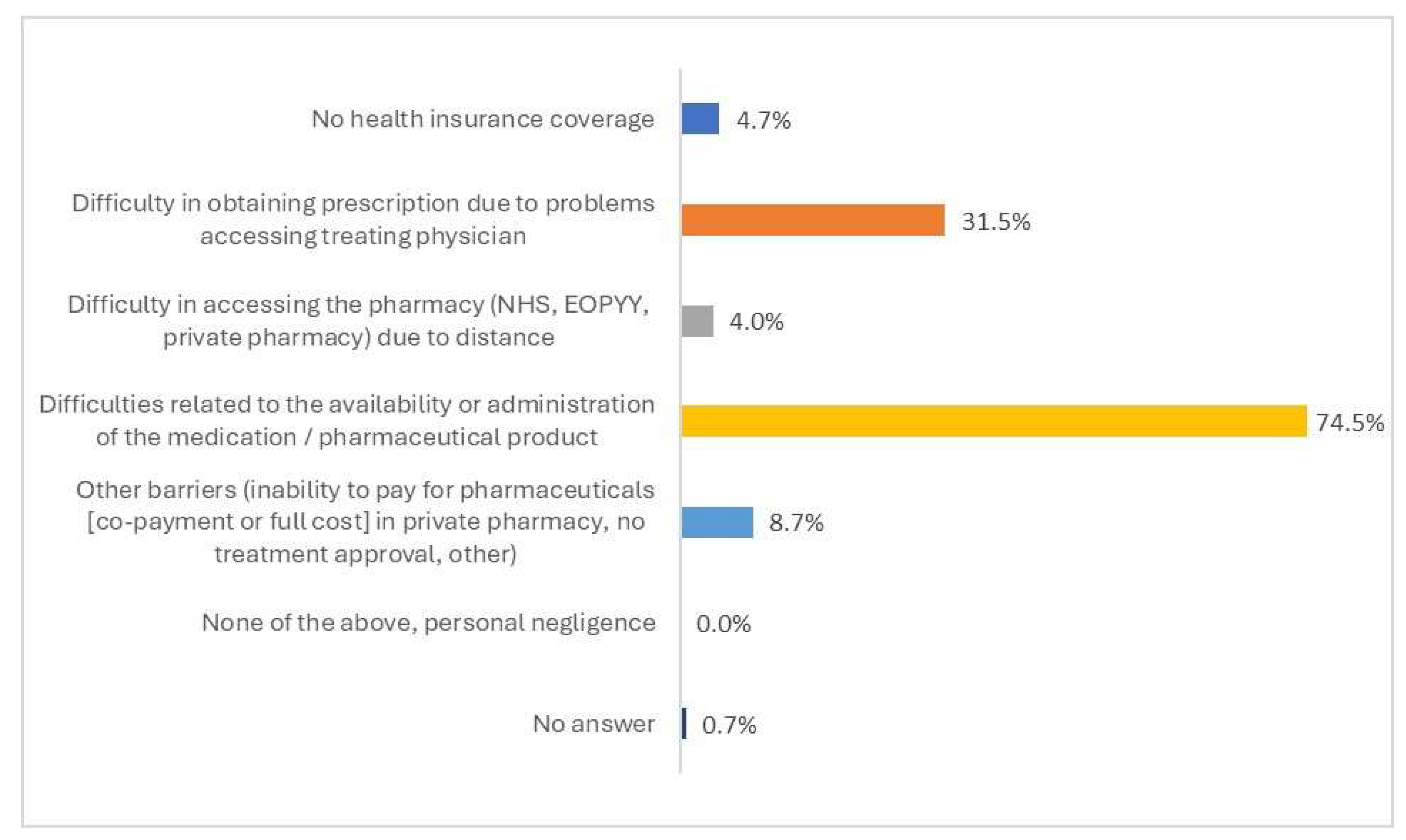

3.3. Barriers to Access to Health Services

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EOPYY | National Organization for Health Care Services |

| EU | European Union |

| NHS | National Health System |

References

- Campbell, S.M.; Roland, M.O.; Buetow, S.A. Defining quality of care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, R.J. Quality assessment in health. BMJ 1984, 288, 1470–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. The seven pillars of quality. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1990, 114, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, D.; Gibson, B.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, S.; Masseria, C. Research Note: Unmet Need as an Indicator of Access to Health Care in Europe. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Research Note. 2009. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=c5a2f79ff01396a7e4affa9540a29ae71c83ac0d (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Zavras, D.; Zavras, A.I.; Kyriopoulos, I.I.; Kyriopoulos, J. Economic crisis, austerity and unmet healthcare needs: The case of Greece. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, S.; Grignon, M.; Le Grand, J. Subjective unmet need and utilization of health care services in Canada: What are the equity implications? Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Report, 27 August 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Greece: Country Health Profile 2023, State of Health in the EU; OECD: Paris, France; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, C.; Kaitelidou, D.; Karanikolos, M.; Maresso, A. Greece: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2017, 19, 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Karanikolos, M.; Kentikelenis, A. Health inequalities after austerity in Greece. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riza, E.; Kakalou, E.; Nitsa, E.; Hodges-Mameletzis, I.; Goggolidou, P.; Terzidis, A.; Cardoso, E.; Puchner, K.P.; Solomos, Z.; Pikouli, A.; et al. Appraisal of a Contact Tracing Training Program for COVID-19 in Greece Focusing on Vulnerable Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, C. Greece’s healthcare system and the crisis: A case study in the struggle for a capable welfare state O sistema de saúde grego e a crise: Um estudo de caso na luta pela capacidade do Estado Social Case studies from countries with adjustment programmes contracted with the Troika. An. Inst. Hig. Med. Trop. 2018, 17, S7–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Golna, C.; Tountas, Y.; Siskou, O.; Kaitelidou, D.; Liaropoulos, L. Informal payments in the Greek health sector amid the financial crisis: Old habits die last. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2016, 17, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouchos, T.V.; Vozikis, A.; Koufopoulou, P.; Fawkes, L.; Souliotis, K. Informal out-of-pocket payments for healthcare services in Greece. Health Policy 2020, 124, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Golna, C.; Nikolaidi, S.; Vatheia, G.; Hasurdjiev, S. Access to health care for patients with thalassaemia in Greece: A cross-sectional study. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Astolfi, R. Health Spending Growth at Zero: Which Countries, Which Sectors Are Most Affected? 2013. Available online: www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2013/01/health-spending-growth-at-zero_g17a222d/5k4dd1st95xv-en.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Kentikelenis, A.; Karanikolos, M.; Papanicolas, I.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Health effects of financial crisis: Omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011, 378, 1457–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, E.; Kontodimopoulos, N.; Papadopoulos, A.; Tountas, Y.; Niakas, D. Investigating unmet health needs in primary health care services in a representative sample of the Greek population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondilis, E.; Tarantilis, F.; Benos, A. Essential public healthcare services utilization and excess non-COVID-19 mortality in Greece. Public Health 2021, 198, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krubiner, C.; Keller, J.M.; Kaufman, J. Balancing the COVID-19 Response with Wider Health Needs: Key Decision-Making Considerations for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. CGD Note. 2020. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/balancing-covid-19-response-wider-health-needs-key-decision-making-considerations-low (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Eurostat. Unmet Health Care Needs Statistics. Statistics Explained. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_silc_08b__custom_8939548/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=be2775d3-d56f-4098-909b-e3ae089f8b7f (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Tsiakalakis, G.; Golna, C.; Dedes, N.; Athanasakis, K.; Souliotis, K. HIV patient access to healthcare services in post-austerity era in Greece. Int. J. Hum. Rights Health 2021, 14, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Agapidaki, E.; Papageorgiou, M. Healthcare access for cancer patients in the era of economic crisis. Results from the HOPE III study. Forum Clin. Oncol. 2015, 6, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Papageorgiou, M.; Politi, A.; Ioakeimidis, D.; Sidiropoulos, P. Barriers to accessing biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in Greece: The unseen impact of the fiscal crisis–the Health Outcomes Patient Environment (HOPE) study. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Agapidaki, E.; Papageorgiou, M.; Voudouri, N.; Contiades, X. Access to treatment for Hepatitis C among injection drug users: Results from the cross-sectional HOPE IV study. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Alexopoulou, E.; Papageorgiou, M.; Politi, A.; Litsa, P.; Contiades, X. Access to Care for Multiple Sclerosis in Times of Economic Crisis in Greece–the HOPE II Study. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2015, 5, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.S. Sampling. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed.; Peterson, P., Baker, E., McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- (ELSTAT) HSA. Census Results of Population and Housing 2021 Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2022. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/2021-census-pop-hous (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Manor, O.; Matthews, S.; Power, C. Dichotomous or categorical response? Analysing self-rated health and lifetime social class. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 29, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souliotis, K.; Tsimtsiou, Z.; Golna, C.; Nikolaidi, S.; Lionis, C. Citizen Preferences for Primary Health Care reform in Greece. Hippokratia 2019, 23, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani, N.; Wagstaff, A.; van Doorslaer, E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: Measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J. Econom. 1997, 77, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erreygers, G. Correcting the concentration index. J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Doorslaer, E.; Van Ourti, T. Measuring Inequality and Inequity in Health and Health Care; Glied, S., Smith, P.C., Eds.; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 837–869. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, O.; O’Neill, S.; Van Ourti, T.; Walsh, B. Conindex: Estimation of concentration indices. Stata J. 2016, 16, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, C. Barriers and Facilitating Factors in Access to Health Services in Greece; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriopoulos, I.-I.; Zavras, D.; Skroumpelos, A.; Mylona, K.; Athanasakis, K.; Kyriopoulos, J. Barriers in access to healthcare services for chronic patients in times of austerity: An empirical approach in Greece. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrakos, G.; Goula, A.; Latsou, D. Predictors of Unmet Healthcare Needs during Economic and Health Crisis in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurofound. Economic and Social Inequalities in Europe in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Souliotis, K.; Papadonikolaki, J. Resilient health reforms in times of permacrisis: The Greek citizens’ perspective. Front. Political Sci. 2024, 6, 1470412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics | No. of Respondents | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 1002 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 520 | 51.9 |

| Women | 482 | 48.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤24 | 80 | 8.0 |

| 25–39 | 153 | 15.3 |

| 40–54 | 280 | 27.9 |

| 55–64 | 256 | 25.5 |

| ≥65 | 233 | 23.3 |

| Education | ||

| Basic | 24 | 2.5 |

| Secondary | 217 | 21.7 |

| Higher | 495 | 49.5 |

| Postgraduate (Master’s degree or PhD) | 263 | 26.3 |

| Geographical area of residence | ||

| Attica | 435 | 43.4 |

| Thessaloniki | 104 | 10.4 |

| Northern Greece | 136 | 13.6 |

| Central Greece | 251 | 25.0 |

| Aegean–Crete | 76 | 7.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 207 | 21.1 |

| Married/cohabitating | 650 | 66.2 |

| Divorced | 90 | 9.2 |

| Widowed | 35 | 3.5 |

| Profession | ||

| Agricultural, fishery worker | 9 | 0.9 |

| Shop and market sales worker | 17 | 1.7 |

| Business owner/businessman | 38 | 3.9 |

| Public sector employee | 174 | 17.8 |

| Private sector employee | 181 | 18.5 |

| Scientist, self-employed, technical assistant | 128 | 13.1 |

| Not working/seeking work for first time | 169 | 17.3 |

| Retired | 262 | 26.8 |

| Total monthly income (EUR) | ||

| No income | 10 | 1.1 |

| ≤500 | 39 | 4.4 |

| EUR 501–1000 | 196 | 22.3 |

| EUR 1001–1500 | 232 | 26.5 |

| EUR 1501–2000 | 176 | 20.0 |

| >2001 | 226 | 25.7 |

| Self-evaluation of monthly income | ||

| Low/fair to low | 588 | 59.3 |

| Fair | 314 | 31.6 |

| Fair to high/high | 90 | 9.1 |

| Health insurance status | ||

| Insured | 927 | 93.6 |

| Not insured/welfare | 63 | 6.4 |

| Private insurance coverage | ||

| Yes | 176 | 17.8 |

| No | 812 | 82.2 |

| Type of services covered by private insurance (if yes) * | ||

| Physician visit | 81 | 48.5 |

| Diagnostic tests | 96 | 57.5 |

| Hospitalization | 150 | 90.0 |

| Item | No. of Respondents | % |

|---|---|---|

| Health Status | ||

| Very bad/bad | 90 | 9.0 |

| Moderate | 237 | 23.9 |

| Good/very good | 668 | 67.1 |

| Frequency of using health services for preventive health check-up | ||

| Very often/often | 407 | 40.8 |

| Sometimes | 376 | 37.7 |

| Rarely/never | 214 | 21.5 |

| Use of health services in the past 12 months | ||

| Yes | 837 | 83.5 |

| No | 165 | 16.5 |

| Type of health services used | ||

| Total | 837 | 100.0 |

| Medical consultation | 691 | 82.6 |

| Dental care visit | 376 | 44.9 |

| Diagnostic and laboratory tests | 675 | 80.6 |

| Hospitalization | 135 | 16.1 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 532 | 63.6 |

| Self-Reported Access Barriers (Yes/No) | Medical Consultation (n [%]) | Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests (n [%]) | Hospitalization (n [%]) | Pharmaceuticals (n [%]) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Total population | 330 (47.8) | 331 (47.9) | 228 (33.8) | 413 (61.2) | 54 (40.0) | 75 (55.6) | 149 (28.0) | 349 (65.6) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 152 (46.2) | 163 (49.5) | 112 (33.9) | 201 (60.9) | 31 (40.3) | 44 (57.1) | 72 (27.3) | 181 (68.6) |

| Women | 178 (49.2) | 168 (46.4) | 116 (33.6) | 212 (61.4) | 23 (39.7) | 31 (53.4) | 77 (28.7) | 168 (62.7) |

| Total monthly income (EUR) | ||||||||

| ≤500 | 24 (70.6) | 10 (29.4) | 14 (46.7) | 16 (53.3) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (40.0) | 13 (52.0) |

| 501–1000 | 71 (53.8) | 54 (40.9) | 50 (39.7) | 69 (54.8) | 14 (46.7) | 15 (50.0) | 29 (26.9) | 65 (60.2) |

| 1001–1500 | 85 (54.1) | 69 (43.9) | 52 (34.2) | 93 (61.2) | 13 (46.4) | 14 (50.0) | 43 (33.9) | 80 (63.0) |

| 1501–2000 | 58 (44.6) | 63 (48.5) | 46 (36.2) | 71 (55.9) | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | 24 (26.4) | 62 (68.1) |

| >EUR 2001 | 56 (34.8) | 97 (60.2) | 40 (24.7) | 114 (70.4) | 9 (25.7) | 24 (68.6) | 30 (24.0) | 91 (72.8) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ≤24 | 17 (33.3) | 31 (60.8) | 8 (23.5) | 23 (67.6) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 10 (29.4) | 18 (52.9) |

| 25–39 | 33 (34.7) | 59 (62.1) | 24 (25.3) | 65 (68.4) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) | 22 (39.3) | 30 (53.6) |

| 40–54 | 102 (55.4) | 73 (39.7) | 75 (41.7) | 97 (53.9) | 12 (38.7) | 16 (51.6) | 37 (27.6) | 91 (67.9) |

| 55–64 | 104 (52.5) | 87 (43.9) | 73 (36.5) | 119 (59.5) | 25 (51.0) | 23 (46.9) | 51 (31.3) | 106 (65.0) |

| ≥65 | 74 (45.4) | 81 (49.7) | 48 (28.9) | 109 (65.7) | 10 (28.6) | 23 (65.7) | 29 (20.0) | 104 (71.7) |

| Geographical area of residence | ||||||||

| Attica | 147 (47.0) | 154 (49.2) | 93 (30.7) | 198 (65.3) | 24 (39.3) | 34 (55.7) | 65 (25.8) | 175 (69.4) |

| Thessaloniki | 32 (44.4) | 40 (55.6) | 25 (34.2) | 48 (65.8) | 5 (41.7) | 6 (50.0) | 15 (27.8) | 33 (61.1) |

| Northern Greece | 48 (48.5) | 47 (47.5) | 39 (41.9) | 53 (57.0) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | 23 (30.3) | 50 (65.8) |

| Central Greece | 78 (49.7) | 68 (43.3) | 52 (33.1) | 85 (54.1) | 15 (38.5) | 22 (56.4) | 39 (34.8) | 61 (54.5) |

| Aegean–Crete | 25 (50.0) | 22 (44.0) | 19 (38.8) | 29 (59.2) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 7 (18.4) | 30 (78.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souliotis, K.; Golna, C.; Baka, A.; Ntokou, A.; Zavras, D. Barriers in Access to Healthcare Services in Greece Post-COVID-19: Persisting Challenges for Health Policy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151867

Souliotis K, Golna C, Baka A, Ntokou A, Zavras D. Barriers in Access to Healthcare Services in Greece Post-COVID-19: Persisting Challenges for Health Policy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151867

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouliotis, Kyriakos, Christina Golna, Agni Baka, Aikaterini Ntokou, and Dimitris Zavras. 2025. "Barriers in Access to Healthcare Services in Greece Post-COVID-19: Persisting Challenges for Health Policy" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151867

APA StyleSouliotis, K., Golna, C., Baka, A., Ntokou, A., & Zavras, D. (2025). Barriers in Access to Healthcare Services in Greece Post-COVID-19: Persisting Challenges for Health Policy. Healthcare, 13(15), 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151867