Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Recruiting Young Adolescents (Age 10–14) in Sexual Health Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

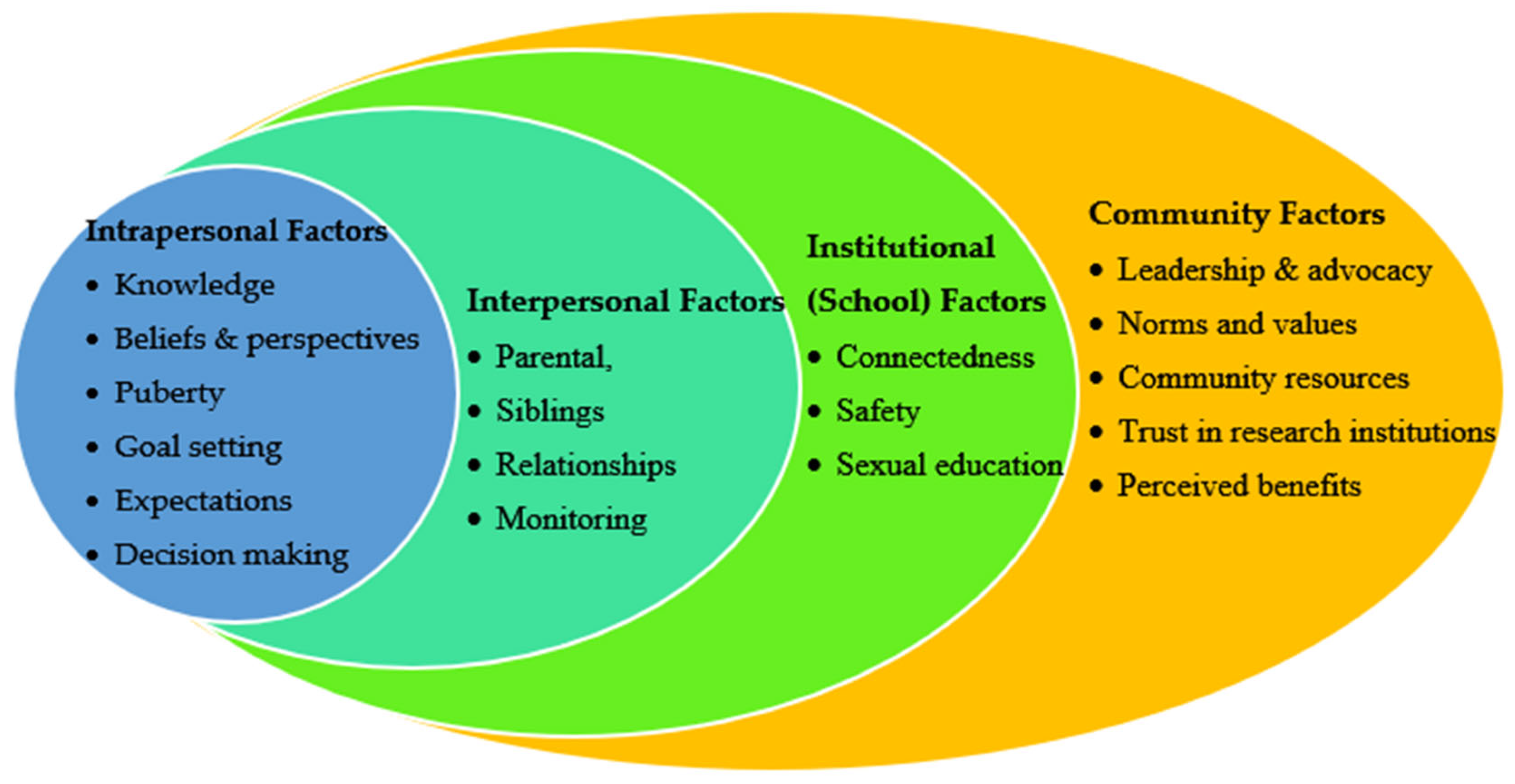

2.1. The Conceptual Framework

2.2. Sample and Sampling

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Positionality Statement

3. Results

3.1. Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Conducting Sexual Health Research with Young Adolescents

3.1.1. Perceived Benefits

“I think that engaging young adolescents in research would be very helpful, because now we’ll be able to see where their minds are at, what they do know or what they have experienced. And then that allows us to build on what they have provided us with when we are thinking of their care [meaning sexual health support and intervention]”(staff from the youth recreation center)

“So, my views are that they’re probably seeing it, It’s everywhere, right? Social media, their friends are probably talking about it. So, I think it’s important to make sure to reach them young because they’re going to hear about it and others are already hearing it. And if I would, I would rather have a youth have a positive outlook on safe sex than a negative outlook. Because 5, 10, 15 years down the line they may have an STD or an STI or have a child which may impact their self-esteem. So maybe if someone can sit down with them: well, what are your views on sexual health? Then, why do you feel this way? That can help”.

“Because it’s really important to gauge their knowledge while they are young. If we think back to when we were between 10 and 14, with all the misinformation, I believe that it may still be the case, that kids talk, they have misinformation. But we don’t know what is it that they’re believing nowadays? But kids, need to know what’s going on around at this age. So, we need to know, what they know so we can give them more information, and one way of knowing is to engage the in research”(a sexual health education teacher)

3.1.2. A Missing Piece

“Hearing sexual health issues from the perspective of a young person, I absolutely think that’s a missing piece and an incredibly valuable area that I would imagine has gone largely unexplored. Not to say exclusively, but what would that be like to actually work with young people and hearing from them what has been helpful, what has been missing in terms of them better understanding their bodies, their development, attitudes towards sexual health and development, the supports that they need What are the barriers to that? Yeah, that would be a very different conversation, I think that would be a much-needed perspective to have.”

3.1.3. Safety as a Pathway to Young Adolescent Engagement in Research

“I’m just going to be blunt. 10- to 14-year-olds really like to talk. Sometimes it’s unhealthy chatter. What we need is to make sure we provide that safe space for them so that they can talk. I will say you should build in a confidentiality. Tell them that, “we want you to allow us talk to you in this space. This is the forum and platform for that space. However, though, if we do hear something, then that is going to lead to more questioning and making sure we are protecting you and your safety.”

“I mean, I ask them straight out. They’re always like, ‘Miss, that’s so uncomfortable,’ but I’m like, ‘What does sex mean to you,’ and they’re like, ‘It’s the first time we’ve met with you,’ and I’m like, ‘I know, this is the first time you meet with me, so uncomfortable, but this is our safe space.’ I try to make a joke out of it. They’ll be like, ‘Well, it means two people’s private parts are touching.’ ‘Great. What do you do to make sure that that’s safe?’ So, it depends on the youth and how you convince them of their safety”(a youth counselor)

3.2. Recruitment Strategies

3.2.1. Parental Understanding as a Gateway to Recruitment

“You need parents and guardians. You need their buy-in, because a lot of times, they get scared. ‘What are you talking to my kids about?’ And there’s this whole idea, like, that’s [meaning having sexual health conversations] not someone’s responsibility or the school’s responsibility, that’s the parents’ responsibility. So, unless they understand what you are going to talk about and why, they cannot allow their kids to participate. I would actually say, you come with evidence and what exactly you need them [the young adolescents] to do. Those things will help them understand. Because sometimes if you say sexual, and they are like, ‘oh no, you’re not talking to my child about this and that.’ So, use terms that they would understand, let them know how it’s going to impact them as parents, how it’s going to impact their child and what’s going to happen”(staff at a recreation center)

“I really think doing more targeted work with parents. Because that’s a big barrier. I think because a lot of parents today likely didn’t receive good enough sexual health education. So, engaging them in research provides an opportunity to give them information. Maybe if someone can sit down with them [parents], well, what are your views on sexual health then? Why do you feel this way? And then introduce your research and them facts about the importance of the research, it can help. I think when a parent feels heard and seen, then they’re more likely to hear and see their own children with sexual health lens and be open to allow them to participate. And I think once you start with the parent and getting their information, their views, and then talk with the child on their own, it can help to have a more balanced views and a well-informed approach to supporting young adolescents”(a youth counselor)

3.2.2. Collaboration with Schools and Youth Organizations

“I have found that it’s easier when you have a relationship with the school and then the school does some of that legwork because it means more coming from the school than from the researcher. Talking to the community engagement person, community organizations already working with schools, or the assistant principal and explain, ‘This is what we’re doing, could you reach out to parents for us?’ And then flyers on social media and just places that parents and youth might engage with”(member of a youth-based organization)

“I feel like the best connection is within the schools because the kids are there, especially a lot of times after school, like pick up and stuff like that. Also, a lot of the schools will have parent liaisons or connection with the parents that way”(a youth counselor)

3.2.3. Providing a Safe Space

“I would definitely say building a relationship with the youth where they know that you are a safe place and that you’re not going to run back and tell mom and dad what they said, or you’re not going to run and go tell someone else. And just making sure that they are reassured that their information stays confidential.”

“I will say you should build in confidentiality. Tell them that: ‘We want you to be safe. This is the forum and platform for that safe space. However, though, if we do hear something, then that is going to lead to more questioning and making sure we are protecting you and your safety.’”

3.2.4. Utilizing Non-Sexualized Messaging

“I feel like the kids would be more inclined to join than the parents. I don’t know. Would you call it [the study] sexuality? That is my question. I don’t know. I have an eight-year-old. He’s almost nine in a couple months. If I asked him that, he would be like, ugh. He would be like mortified and embarrassed, I think I just wonder if you could call it something else that’s a little less intimidating to a kid that age, that might be something to think about.”

3.2.5. Incentives

“I would say it’s definitely hard to recruit youth, but I would say incentives, sometimes food is a really big incentive. If you come here, there will be pizza or maybe there’ll be insomnia cookies. Or if you participate, there is a $10 gift card, or $20 gift card. So, I think incentives is a big one”(a youth counselor)

“Being able to give them incentive in some way, not necessarily monetary incentive, but some type of incentive that would keep them wanting to participate. I don’t know. Something that’ll make them feel appreciated.”

3.3. Research Questions

3.4. Buidling Readiness for Participation in Sexual Health Research

“It really starts when they [children] are getting curious about their private parts. We really need to teach our children the proper names of our body parts. And so that’s a sexual health conversation. I’ve had conversation with my adult children, that, ‘Okay, we’re not using these cute names, you need to tell your son, ‘That is a penis.’ You need to tell your daughters that they have a vagina, so they can say, ‘he had me touch his penis’ or ‘he put his finger on my vagina’. So really, sexual health incorporates that at a very young age. We’re really talking probably at 18 months to two years when they’re starting to talk and recognize those things. When we normalize these conversations, they cannot feel embarrassed to talk about them in a research setting”(a health educator)

“I think five is appropriate. I think five-year-olds are very touchy with each other. They are still exploring their bodies. And I think learning about consent at that age is developmentally appropriate. I think they’ve already learned about sharing. Right? That’s developmentally appropriate. And so, sharing their bodies with other people, that conversation makes sense at that. I think sex education that young adolescents should look like relationship building, friendship building, and what it’s like to listen to your body. Starting early like this lays the groundwork and helps prepare them to meaningfully engage in sexual health conversations—and, eventually, in research”(a health counselor)

“I think somewhere between eight and 10, depending on the kid’s developmental stage. My son is eight right now and I just bought a book, a children’s book to review with him because I did not really feel ready and prepared to talk with him about it, but I heard that one of his little peers at school was an eight-year-old and making little like jokes and comments. And I was like, oh, okay, well he’s hearing it at school. I want to make sure that I can chat with them at home about some things at high level.”

“I would say I think 12 is a good age to start engaging them in sexual health conversations and is a good time too that they can participate in research, but I can also, say that I think we’re living in a different time, in a different generation. And so maybe there may be a need to go younger and I think it’s important to use language that is appropriate for each age group, right? So, the language you may use with a 16, 17-year-old, you probably shouldn’t use with a 12-year-old.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBPR | Community-based participatory research |

| INSHHR | Interdisciplinary sexual health and HIV research |

| NY | New York |

| STIs | Sexually transmitted infections |

| SRH | Sexual and reproductive health |

References

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Afifi, R.A.; Bearinger, L.H.; Blakemore, S.J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A.C.; Patton, G.C. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, S.L.; Blum, R.W.; Lai, J. Adolescents’ perceptions of mental health around the world: Key findings from a 13-country qualitative study. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muheriwa-Matemba, S.R.; Anson, E.; McGregor, H.; Zhang, C.; Crooks, N.; LeBlanc, N.M. Prevalence of early sexual debut among young adolescents in ten states of the United States. Adolescents 2024, 4, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlecht, N.F.; Diaz, A.; Nucci-Sack, A.; Shyhalla, K.; Shankar, V.; Guillot, M.; Hollman, D.; Strickler, H.D.; Burk, R.D. Incidence and types of human papillomavirus infections in adolescent girls and young women immunized with the human papillomavirus vaccine. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, H.R.; McDermott, C.; Hickey, L.; Issartel, J.; Meegan, S.; Morrissey, J.; Murrin, C.; Peers, C.; Smith, C.; Spillane, A.; et al. Understanding disadvantaged adolescents’ perception of health literacy through a systematic development of peer vignettes. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woog, V.; Kågesten, A. The Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of Very Young Adolescents Aged 10–14 in Developing Countries: What Does the Evidence Show? Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hirth, J.; McGrath, C.J.; Kuo, Y.F.; Rupp, R.E.; Starkey, J.M.; Berenson, A.B. Impact of human papillomavirus vaccination on racial/ethnic disparities in vaccine-type human papillomavirus prevalence among 14–26 year old females in the U.S. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7682–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darroch, J.E.; Woog, V.; Bankole, A.; Ashford, L.S. Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, B. Adolescent capacity to consent to participate in research: A review and analysis informed by law, human rights, ethics, and developmental science. Laws 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Powell, M.; Taylor, N.; Anderson, D.; Fitzgerald, R. Ethical Research Involving Children; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, H.; Gibbs, L.; Marinkovic, K.; Brito, I.; Sheikhattari, P. Children and adolescents’ voices and the implications for ethical research. Childhood 2022, 29, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. Children as researchers in Nicaragua: Children’s consultancy to transformative research. Glob. Stud. Child. 2015, 5, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Boydell, N.; Blake, C.; Clarke, Z.; Kernaghan, K.; McMellon, C. Involving young people in sexual health research and service improvement: Conceptual analysis of patient and public involvement (PPI) in three projects. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2023, 49, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health, in Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children; Field, M.J., Behrman, R.E., Eds.; National Academies Press National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (Ed.) Convention on the Rights of the Child: General Comment NO. 12 (2009): The Right of the Child to be Heard, in CRC/C/GC/12; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Darroch, J.E.; Singh, S.; Woog, V.; Bankole, A.; Ashford, L.S. Research Gaps in Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, P.; Clark, T.C.; Renfrew, L.; Habito, M.; Ameratunga, S. Advancing impactful research for adolescent health and wellbeing: Key principles and required technical investments. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 7, S47–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, C.; Sá, L.; Santos, P. Adolescents’ knowledge and misconceptions about sexually transmitted infections: A cross-sectional study in middle school students in Portugal. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun-Courville, D.K.; Schlecht, N.F.; Burk, R.D.; Strickler, H.D.; Rojas, M.; Lorde-Rollins, E.; Nucci-Sack, A.; Hollman, D.; Linares, L.O.; Diaz, A. Strategies for conducting adolescent health research in the clinical setting: The Mount Sinai adolescent health center HPV experience. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, e103–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faruqui, N.; Dawson, A.; Steinbeck, K.; Fine, E.; Mooney-Somers, J. Research ethics of involving adolescents in health research studies: Perspectives from Australia. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 75, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjani, N.S.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Hegadoren, K. Potential ethical challenges to adolescents’participation in sexual health research. i-Manager’s J. Nurs. 2020, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, S.; Broome, M.E. Understanding ethical issues of research participation from the perspective of participating children and adolescents: A systematic review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, T.M.; Abramovitch, R.; Zlotkin, S. Children’s understanding of the risks and benefits associated with research. J. Med. Ethics 2005, 31, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. Piaget’s Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Muuss, R.E. Jean Piaget’s cognitive theory of adolescent development. Adolescence 1967, 2, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship; Innocenti Essays: Florence, Italy, 1992; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Askari, G.; Vajdi, M.; Jafari-Nasab, S.; Golpour-Hamedani, S. Ethical guidelines for human research on children and adolescents: A narrative review study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 29, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. APA Resolution on Support for the Expansion of Mature Minors’ Ability to Participate in Research; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski, B.; Fisher, C.B. HIV rates are increasing in gay/bisexual teens: IRB barriers to research must be resolved to bend the curve. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.B. Enhancing the responsible conduct of sexual health prevention research across global and local contexts: Training for evidence-based research ethics. Ethics Behav. 2015, 25, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landers, S.E.; Francis, J.K.R.; Morris, M.C.; Mauro, C.; Rosenthal, S.L. Adolescent and parent perceptions about participation in biomedical sexual health trials. Ethics Hum. Res. 2020, 42, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sheyab, N.A.; Alomari, M.A.; Khabour, O.F.; Shattnawi, K.K.; Alzoubi, K.H. Assent and consent in pediatric and adolescent research: School children’s perspectives. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS); World Health Organization. International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), Ed.; CIOMS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74.

- Midgley, N.; Isaacs, D.; Weitkamp, K.; Target, M. The experience of adolescents participating in a randomised clinical trial in the field of mental health: A qualitative study. Trials 2016, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Duran, N.; Norris, K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, A.; Raymond-Flesch, M.; Hughes, S.D.; Zhou, Y.; Koester, K.A. Lessons learned with a triad of stakeholder advisory boards: Working with adolescents, mothers, and clinicians to design the trust study. Children 2023, 10, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deverka, P.A.; Lavallee, D.C.; Desai, P.J.; Esmail, L.C.; Ramsey, S.D.; Veenstra, D.L.; Tunis, S.R. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: Defining a framework for effective engagement. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012, 1, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, S.C.; Butler, J., 3rd; Fryer, C.S.; Garza, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Ryan, C.; Thomas, S.B. Attributes of researchers and their strategies to recruit minority populations: Results of a national survey. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2012, 33, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanje, G.; Masese, L.; Avuvika, E.; Baghazal, A.; Omoni, G.; Scott McClelland, R. Parents’ and teachers’ views on sexual health education and screening for sexually transmitted infections among in-school adolescent girls in Kenya: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blas, V.; Mew, E.J.; Winschel, J.; Hunt, L.; Soliai Lemusu, S.I.; Lowe, S.R.; Naseri, J.; Toelupe, R.L.M.; Hawley, N.L.; McCutchan-Tofaeono, J. Community perspectives on adolescent mental health stigma in American Samoa. PLoS Ment. Health 2024, 1, e0000080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oridota, O.; Shetty, A.; Elaiho, C.R.; Phelps, L.; Cheng, S.; Vangeepuram, N. Perspectives from diverse stakeholders in a youth community-based participatory research project. Eval. Program Plann 2023, 99, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; Board, T.L.A.; Straits, K.J.E.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Espinosa, P.R.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, M.L.; Njeru, J.W.; Weis, J.A.; Lohr, A.; Nigon, J.A.; Goodson, M.; Osman, A.; Molina, L.; Ahmed, Y.; Capetillo, G.P.; et al. Rochester healthy community partnership: Then and now. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1090131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamek, K.; Meckstroth, A.; Inanc, H.; Ochoa, L.; O’Neil, S.; McDonald, K.; Zaveri, H. Conceptual Models to Depict the Factors That Influence the Avoidance and Cessation of Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Youth; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/conceptual-models-depict-factors-influence-avoidance-and-cessation-sexual-risk (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Georgiadis, J.R.; Kringelbach, M.L. The human sexual response cycle: Brain imaging evidence linking sex to other pleasures. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012, 98, 49–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flicker, S.; Travers, R.; Guta, A.; McDonald, S.; Meagher, A. Ethical dilemmas in community-based participatory research: Recommendations for institutional review boards. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalet, A.T.; Santelli, J.S.; Russell, S.T.; Halpern, C.T.; Miller, S.A.; Pickering, S.S.; Goldberg, S.K.; Hoenig, J.M. Invited commentary: Broadening the evidence for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and education in the United States. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baigry, M.I.; Ray, R.; Lindsay, D.; Kelly-Hanku, A.; Redman-MacLaren, M. Barriers and enablers to young people accessing sexual and reproductive health services in Pacific Island Countries and Territories: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; p. 784. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, M.; Chapman, Y.; Francis, K. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. J. Res. Nurs. 2008, 13, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, O.; Daxenberger, L.; Dieudonne, L.; Eustace, J.; Hanard, A.; Krishnamurthi, A.; Quigley, P.; Vergou, A. A Rapid Evidence Review of Young People’s Involvement in Health Research; Wellcome: London, UK, 2020; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Warraitch, A.; Bruce, D.; Lee, M.; Curran, P.; Khraisha, Q.; Hadfield, K. Involving adolescents in the design, implementation, evaluation and dissemination of health research: An umbrella review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akatukwasa, C.; Nyakato, V.N.; Achen, D.; Kemigisha, E.; Atwine, D.; Mlahagwa, W.; Neema, S.; Ruzaaza, G.N.; Coene, G.; Rukundo, G.Z.; et al. Level and comfort of caregiver-young adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health: A cross-sectional survey in south-western Uganda. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aventin, A.; Gough, A.; McShane, T.; Gillespie, K.; O’Hare, L.; Young, H.; Lewis, R.; Warren, E.; Buckley, K.; Lohan, M. Engaging parents in digital sexual and reproductive health education: Evidence from the JACK trial. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, L.J.; Mellins, C.A.; Klitzman, R. Whether to waive parental permission in HIV prevention research among adolescents: Ethical and legal considerations. J. Law Med. Ethics 2020, 48, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raniti, M.; Rakesh, D.; Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M. The role of school connectedness in the prevention of youth depression and anxiety: A systematic review with youth consultation. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, N.; Quigg, Z.; Bates, R.; Jones, L.; Ashworth, E.; Gowland, S.; Jones, M. The contributing role of family, school, and peer supportive relationships in protecting the mental wellbeing of children and adolescents. School Ment. Health 2022, 14, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E.J.; Sprague Martinez, L.; Abraczinskas, M.; Villa, B.; Prata, N. Toward integration of life course intervention and youth participatory action research. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053509H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrow, J.M.; Brannan, G.D.; Khandhar, P.B. Research Ethics; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pampati, S.; Liddon, N.; Dittus, P.J.; Adkins, S.H.; Steiner, R.J. Confidentiality matters but how do we improve implementation in adolescent sexual and reproductive health care? J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiClemente, R.J. Review: Reducing adolescent sexual risk: A theoretical guide for developing and adapting curriculum-based programs. J. Appl. Res. Child. 2011, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, B.; Kim, S.K.; Park, M.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jo, A.R.; Kim, M.J.; Shin, H.N. A meta-analysis of the effects of comprehensive sexuality education programs on children and adolescents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Comprehensive Sexuality Education: For Healthy, Informed and Empowered Learners. 2023. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/health-education/cse (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach, in Sexuality and Sexual Behavior; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 69–138. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Geneva, Switzerland. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/comprehensive-sexuality-education (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Albert Sekhar, M.; Edward, S.; Grace, A.; Pricilla, S.E.; Sushmitha, G. Understanding comprehensive sexuality education: A worldwide narrative review. Cureus 2024, 16, e74788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rough, B.J. Beyond Birds and Bees: Bringing Home a New Message to Our Kids About Sex, Love, and Equality; Seal Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, E.S.; Lieberman, L.D. Three Decades of Research: The case for comprehensive sex education. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics | Range/M | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23–59/41 | |||

| Sex | Female | 16 | 94.1 | |

| Male | 1 | 5.9 | ||

| Race | White | 7 | 41.2 | |

| Black/African American | 9 | 52.9 | ||

| Mixed race: Caucasian–Indian American | 1 | 5.9 | ||

| Education | Undergraduate | 7 | 41.2 | |

| Master’s degree | 10 | 58.8 | ||

| Youth-Related Role | Members of youth-based community organizations | 4 | 23.5 | |

| Health education teachers | 4 | 23.5 | ||

| Youth counselors | 4 | 23.5 | ||

| Adolescent healthcare providers | 2 | 11.8 | ||

| Youth recreation center staff | 1 | 5.9 | ||

| Staff working with youth with disabilities | 2 | 11.8 | ||

| Question Area | Question Category | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual health knowledge | What young adolescents know about sex | “Some of the questions would be, ‘What do you know about sex?’ Find out what they know. And if you start there, maybe you can build on it. What is it that they know? Questions like, ‘Can you get pregnant the first time you have sex?’” (a member of a youth organization board). |

| “It depends on the child. If we have an 11-year-old kid come in and he has a history of maybe gang violence or things like that, I am going to jump right to our questions and expect him to understand. If I have a kid come in who appears to be super innocent, I’m going to start with, ‘What does sex mean to you?’ So, it’s really just understanding your population” (a youth counselor). | ||

| Age at which they were exposed to sexual health information | “What to ask them? I mean, just when did they become knowledgeable about certain sexual health topics? Are they knowledgeable? Have they heard of what an STD is or how they’re transmitted? I just think a female’s cycle, her menstrual cycle, is important. I mean, some of our females are getting their cycle at school for the first time and have no idea what it is and are almost in some sort of hysteria because they’re just confused. So that shouldn’t happen to any young girl” (a member of a youth-based organization). | |

| Knowledge of STIs and menstrual cycle | “I think asking those questions of, well, how do you feel about sex? What do you feel about STDs? What do you feel about the transmission rate? Are you sexually active? Are you around people who are sexually active? What do your friends feel about sex or how they think about it?” (a youth counselor). | |

| Perceptions of having sexual health conversations | “I guess one question would be is are you open to having conversations about sexual health? Do you know what that means? What does that look like for you? How can we meet you where you are to provide what you need? How can we talk about sex and education in the way that you need? So, letting them help create things. What do you see as a need for yourself and for the community and for your peers?” (a member of a youth organization). | |

| Quality of support received during conversations | “I would imagine that asking them within the context of their own family of origin, have they felt that their questions and their curiosities have been adequately answered and supported as they are developing? Are they in an environment where they are able to really talk about questions that they have? And I think that’s a really important place to start because you absolutely can’t compare one young person’s experience to another” (a social worker). | |

| Sexual education | Young adolescents’ perceptions of sexual health education | “Maybe what they think of the sex ed that they’ve received and whether or not it was too much or not enough or just right. I’ve had some young people who’ve been in our program for a couple years who said that we talk about too much sex stuff, but it’s a sexual health program. What do you mean? So, I’d be interested to see what their perceptions are and what their perception is of the education they get in school” (a member of a youth organization board). |

| Young adolescents’ perceptions of other people’s views on sexual health education | What young adolescents think other people think about sexuality education | “What they think their teachers think about that sexual education, and then just how comfortable they are talking to trusted adults about sexual health and then their peers” (a youth counselor). |

| Sexual health needs | What young adolescents’ sexual health needs are | “I guess just, what are their needs? Because I’m sure we’re not meeting all of their needs. So, I’d love to know what those needs are” (an adolescent healthcare provider). |

| Sources of sexual health knowledge | Where young adolescents obtain sexual health information | “It’s also important, to find out whether or not these young adolescents have siblings and what are their siblings sharing with them? Because that’s probably where they’re getting their information from. So probably I think if we had more information regarding that, we could probably do a better job in schools teaching sexual health. I think sexual health needs to be part of a curriculum so kids can make healthy choices” (a health education teacher). |

| “It is important, to find out whether or not these young adolescents have siblings and what are their siblings sharing with them? Because that’s probably where they’re getting their information from” (a health education teacher). | ||

| Exposure to peers | “What type of exposure do they have amongst young people? I have one student I work with who goes to a school of everyone who’s the same gender versus a co-educational setting. So that changes the dynamic of a person’s experience too” (a social worker). | |

| Young adolescents’ perceptions of the available resources | “Yeah. I think my biggest question would be, what resources are beneficial? Where are they getting information from? Are they getting it from social media? Are pamphlets even still beneficial? Do they use them? Do you know what pamphlets are and even look at them anymore? Where would be the best place for us, as adults, to reach them on these things? Because I know I’ve said over and over, we need more means of support. We need to get them resources, but I think it’s a conversation with them of what those resources look like and what they even need in the first place too” (an adolescent clinic healthcare provider). | |

| Sources of information | “I think questions for young adolescents include walking them through their social media about what they see in regard to sexual health, what they don’t see, what they experience around the music they listen to, their neighborhoods, talking to them less about what they’re learning in the classroom, and talk to them more about what they’re learning in life, will really help you navigate, ‘Okay, where do we fill in with education for them’” (a health education teacher). | |

| Sexual behaviors | Dating experiences | “I think finding out if they’re knowledgeable about certain things or if they’ve already been dating. And if they say yes, I would feed questions off of those responses to dig a little deeper and cover the topics that are necessary and important” (a member of a youth-based organization). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muheriwa Matemba, S.R.; Abboud, S.; Jeremiah, R.D.; Crooks, N.; Alcena-Stiner, D.C.; Collen, L.Y.; Zimba, C.C.; Castellano, C.; Evans, A.L.; Johnson, D.; et al. Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Recruiting Young Adolescents (Age 10–14) in Sexual Health Research. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141711

Muheriwa Matemba SR, Abboud S, Jeremiah RD, Crooks N, Alcena-Stiner DC, Collen LY, Zimba CC, Castellano C, Evans AL, Johnson D, et al. Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Recruiting Young Adolescents (Age 10–14) in Sexual Health Research. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141711

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuheriwa Matemba, Sadandaula Rose, Sarah Abboud, Rohan D. Jeremiah, Natasha Crooks, Danielle C. Alcena-Stiner, Lucia Yvone Collen, Chifundo Colleta Zimba, Christina Castellano, Alicia L. Evans, Dina Johnson, and et al. 2025. "Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Recruiting Young Adolescents (Age 10–14) in Sexual Health Research" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141711

APA StyleMuheriwa Matemba, S. R., Abboud, S., Jeremiah, R. D., Crooks, N., Alcena-Stiner, D. C., Collen, L. Y., Zimba, C. C., Castellano, C., Evans, A. L., Johnson, D., Harris, T., & LeBlanc, N. M. (2025). Community Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Recruiting Young Adolescents (Age 10–14) in Sexual Health Research. Healthcare, 13(14), 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141711