Multimorbidity: Addressing the Elephant in the Clinic Room

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Statistics

1.2. Multimorbidity Versus Comorbidity

1.3. The Biopsychosocial Model

1.4. The Role of Clinical Health Psychologists

2. Pain Management Clinic as a Model

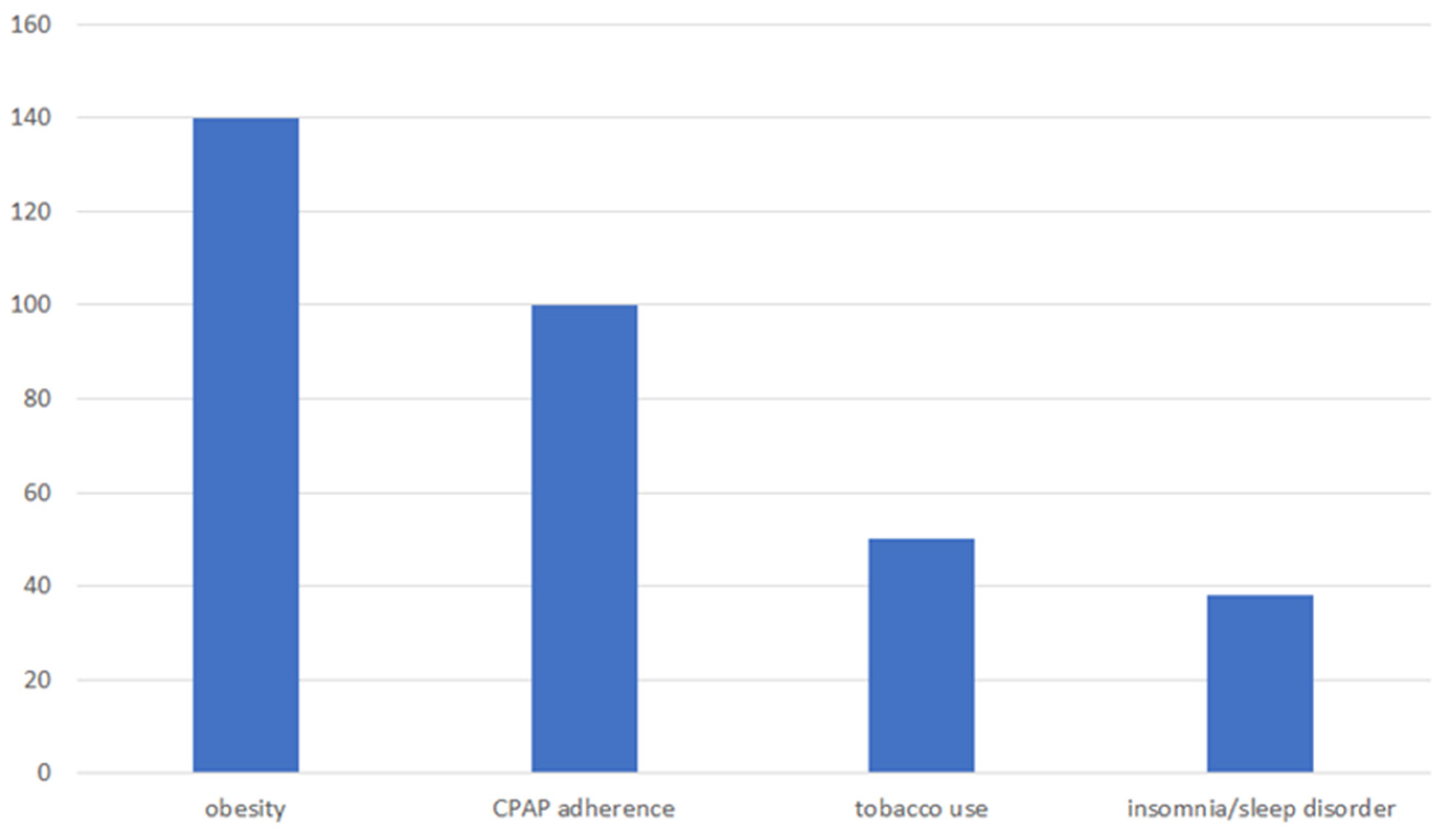

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care, Now More than Ever; World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multimorbidity: Clinical Assessment and Management. 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- USA Department of Health & Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Strategic Framework: Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. 2010. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- King, D.E.; Xiang, J.; Pilkerton, C.S. Multimorbidity trends in United States adults, 1988–2014. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Academy of Medical Sciences. Multimorbidity: A Priority for Global Health Research. 2018. Available online: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/multimorbidity (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Bloeser, K.; Lipkowitz-Eaton, J. Disproportionate multimorbidity among veterans in middle age. J. Public Health 2022, 44, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.R. The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic diseases. J. Chronic Dis. 1970, 23, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.; Mangialasche, F.; Karp, A.; Garmen, A.; Meinow, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Aging Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Marengoni, A.; Onder, G.; Bauer, J.M.; Cesari, M.; Ferrucci, L.; Fratiglioni, L. An international perspective on chronic multimorbidity: Approaching the elephant in the room. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khor, B.; Gardet, A.; Xavier, R.J. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011, 474, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawber, T.R.; Moore, F.E.; Mann, G.V. Coronary heart disease in the Framingham Study. Am. J. Public Health 1957, 47, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubzansky, L.D.; Cole, S.R.; Kawachi, I.; Vokonas, P.; Sparrow, D. Shared and unique contributions of anger, anxiety, and depression to coronary heart disease: A prospective study in the normative aging study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2006, 31, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, L.M.; Taylor, G.; Huxley, R.R.; Mitchell, P.; Woodward, M.; Peters, S.A. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skou, S.T.; Mair, F.S.; Fortin, M.; Guthrie, B.; Nunes, B.P.; Miranda, J.J.; Boyd, C.M.; Pati, S.; Mtenga, S.; Smith, S.M. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Mercer, S.W. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wister, A.V.; Coatta, K.L.; Schuurman, N.; Lear, S.A.; Rosin, M.; MacKey, D. A Lifecourse Model of Multimorbidity Resilience: Theoretical and Research Developments. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 82, 290–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp-Reimer, T.; Williams, J.K.; Gardner, S.E.; Rakel, B.; Herr, K.; McCarthy, A.M.; Hand, L.L.; Gilbertson-White, S.; Cherwin, C. An integrated model of multimorbidity and symptom science. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Green, P.A.; Davidson, K.W. A Biobehavioral Framework to Address the Emerging Challenge of Multimorbidity. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Suls, J.; Green, P.A.; Boyd, C.M. Multimorbidity: Implications and directions for health psychology and behavioral medicine. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.; Okifuji, A. Psychological approaches in pain management: What works? Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 1998, 11, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stange, K.C.; Breslau, E.S.; Dietrich, A.J.; Glasgow, R.E. State-of-the-art and future directions in multilevel interventions across the cancer control continuum. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012, 44, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosio, D.; Lin, E. Effects of a pain education program for veterans with chronic, noncancer pain: A pilot study. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2013, 27, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados-Torres, A.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Hancco-Saavedra, J.; Poblador-Plou, B.; van den Akker, M. Multimorbidity patterns: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Price, R.K. Symptoms in the community: Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993, 153, 2474–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morasco, B.J.; Gritzner, S.; Lewis, L.; Oldham, R.; Turk, D.C.; Dobscha, S.K. Systemic review of prevalence, correlates, and treatment outcomes for chronic non-cancer pain in patients with comorbid substance use disorder. Pain 2011, 152, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muse, M. Stress-related, post-traumatic chronic pain syndrome: Behavioral treatment approach. Pain 1986, 25, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dersh, J.; Polatin, P.; Gatchel, R. Chronic pain and psychopathology: Research findings and theoretical considerations. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shekelle, P.; Miake-Lye, I.; Shanman, R.; Beroes, J. The Effectiveness and Risks of Cranial Electrical Stimulation for the Treatment of Pain, Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, and Insomnia: A Systematic Review; VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Reports; Department of Veterans Affairs (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell, J.L.; Afari, N.; Rutledge, T.; Sorrell, J.T.; Stoddard, J.A.; Petkus, A.J.; Solomon, B.C.; Lehman, D.H.; Liu, L.; Lang, A.J.; et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain 2011, 152, 2098–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duigan, N.; Burke, A. Group based treatment for chronic pain: Is ACT effective and how does it compare to CBT? Poster session presented at ACBS (Association for Contextual Behavioral Science). In Proceedings of the 4th Australian and New Zealand Conference of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Adelaide, Australia, 1–3 October 2010, unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- Veehof, M.M.; Oskam, M.-J.; Schreurs, K.M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2011, 152, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Facts: Treatment Approaches for Drug Addiction. Available online: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/treatment-approaches-drug-addiction (accessed on 6 May 2015).

- Colbert, J.; Jangi, S. Training physicians to manage obesity—Back to the drawing board. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.M. The Burden of Obesity Among a National Probability Sample of Veterans. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doghramji, P.P. Recognition of obstructive sleep apnea and associated excessive sleepiness in primary care. J. Fam. Pract. 2008, 57, S17–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.R.; Kinsinger, L.S.; Yancy, W.S.; Wang, A.; Ciesco, E.; Burdick, M.; Yevich, S.J. Obesity prevalence among veterans at veterans affairs medical facilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.L.; Pietz, K.; Battleman, D.S.; Beyth, R.J. Prevalence of comorbid hypertension and dyslipidemia and associated cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Manag. Care 2004, 10, 926–932. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.; Yaquba, M.; Hinds, J.; Perry, C. A longitudinal analysis of tobacco use in younger and older U. S. veterans. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 16, 100990. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rostron, B.; Chang, C.; Pechacek, T. Estimation of cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1922–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petre, B.; Torbey, S.; Griffith, J.W.; De Oliveira, G.; Herrmann, K.; Mansour, A.; Baria, A.T.; Baliki, M.N.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Apkarian, A.V. Smoking increases risk of pain chronification through shared corticostriatal circuitry. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 36, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Ulmer, C.S.; Gierisch, J.M.; Hastings, S.N.; Howard, M.O. Insomnia in United States military veterans: An integrated theoretical model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 59, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesenberry, C.; Caan, B.; Jacobson, A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltonen, M.; Lindroos, A.; Torgerson, J. Musculoskeletal pain in the obese: A comparison with a general population and long-term changes after conventional and surgical obesity treatment. Pain 2003, 104, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandacoomarasamy, A.; Fransen, M.; March, L. Obesity and the musculoskeletal system. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2009, 21, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M. Tending to the musculoskeletal problems of obesity. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2006, 73, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Arslan, S.; Aldag, J. Relationship between body mass index and fibromyalgia features. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 31, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.; Astrup, A.; Bliddal, H. Weight loss: The treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2005, 13, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, T.; Wren, A.; Keefe, F. Understanding chronic pain in older adults: Abdominal fat is where it is at. Pain 2011, 152, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, L.; Lipton, R.B.; Zimmerman, M.E.; Katz, M.J.; Derby, C.A. Mechanisms of association between obesity and chronic pain in the elderly. Pain 2011, 152, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USA Department of Veterans Affairs; John, D. Dingell VA Medical Center: Sleep Center Education. Available online: https://www.va.gov/detroit-health-care/locations/john-d-dingell-department-of-veterans-affairs-medical-center/ (accessed on 28 March 2014).

- USA Preventative Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: USA Preventative Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Sleep Foundation. What Causes Insomnia? 2014. Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/insomnia/what-causes-insomnia (accessed on 28 March 2014).

- Cosio, D.; Lin, E. Hypnosis & biofeedback: Information for pain management. Pract. Pain. Manag. 2015, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cosio, D.; Lin, E. Spirituality & Healing Touch: How incorporating these practices can help improve pain management. Pract. Pain. Manag. 2015, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- WHO European Working Group on Health Promotion Evaluation. Health Promotion Evaluation: Recommendations to Policy-Makers: Report of the WHO European Working Group on Health Promotion Evaluation. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 1998. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/108116/E60706.pdf?sequence=1#:~:text=The%20present%20report%2C%20which%20is%20a%20summary%20of,for%20planning%2C%20implementing%20and%20evaluating%20health%20promotion%20initiatives (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Borrell-Carrió, F.; Suchman, A.L.; Epstein, R.M. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HHS. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pain-mgmt-best-practices-draft-final-report-05062019.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosio, D. Multimorbidity: Addressing the Elephant in the Clinic Room. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101202

Cosio D. Multimorbidity: Addressing the Elephant in the Clinic Room. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101202

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosio, David. 2025. "Multimorbidity: Addressing the Elephant in the Clinic Room" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101202

APA StyleCosio, D. (2025). Multimorbidity: Addressing the Elephant in the Clinic Room. Healthcare, 13(10), 1202. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101202