A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

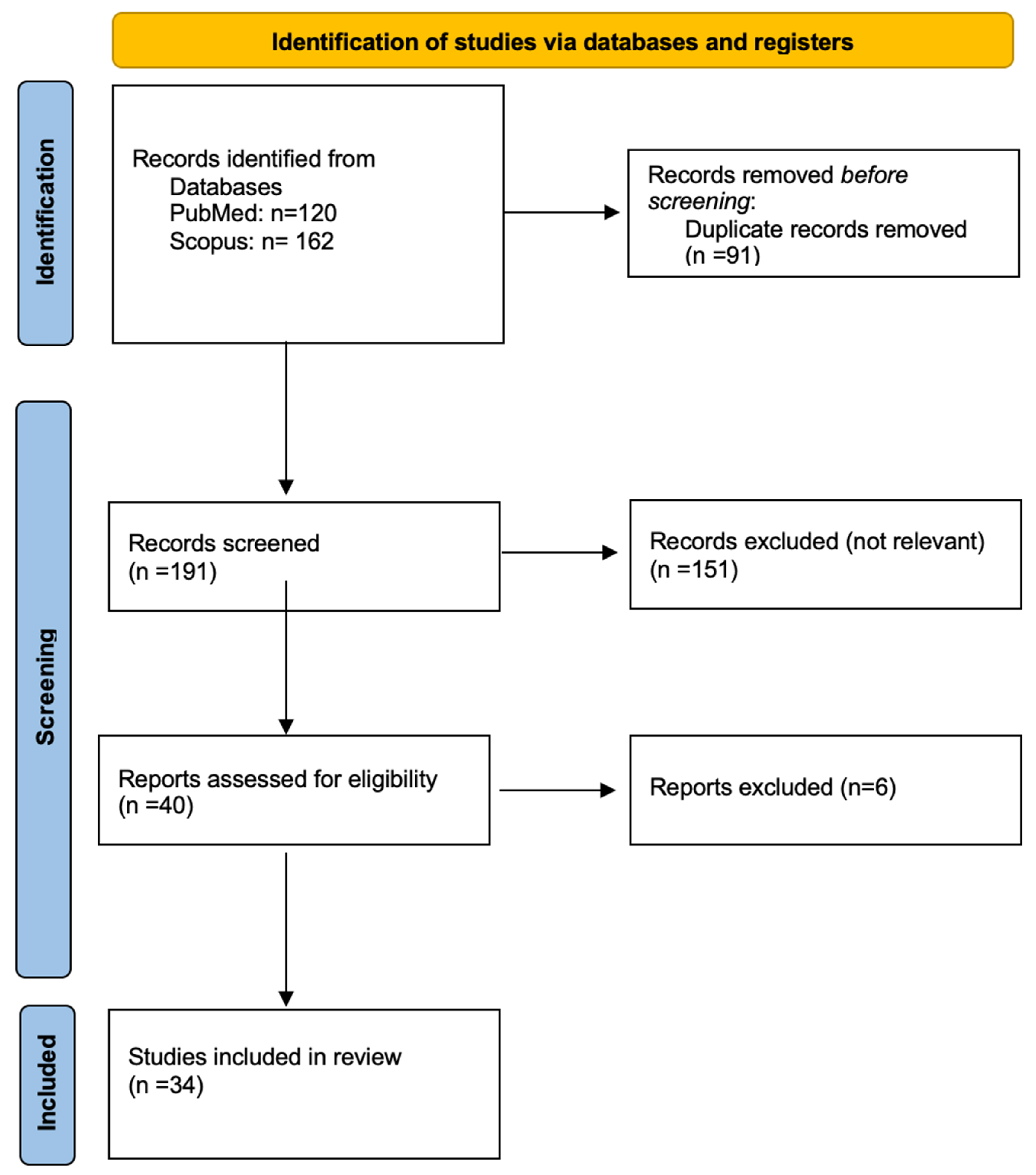

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Search Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias Assessment

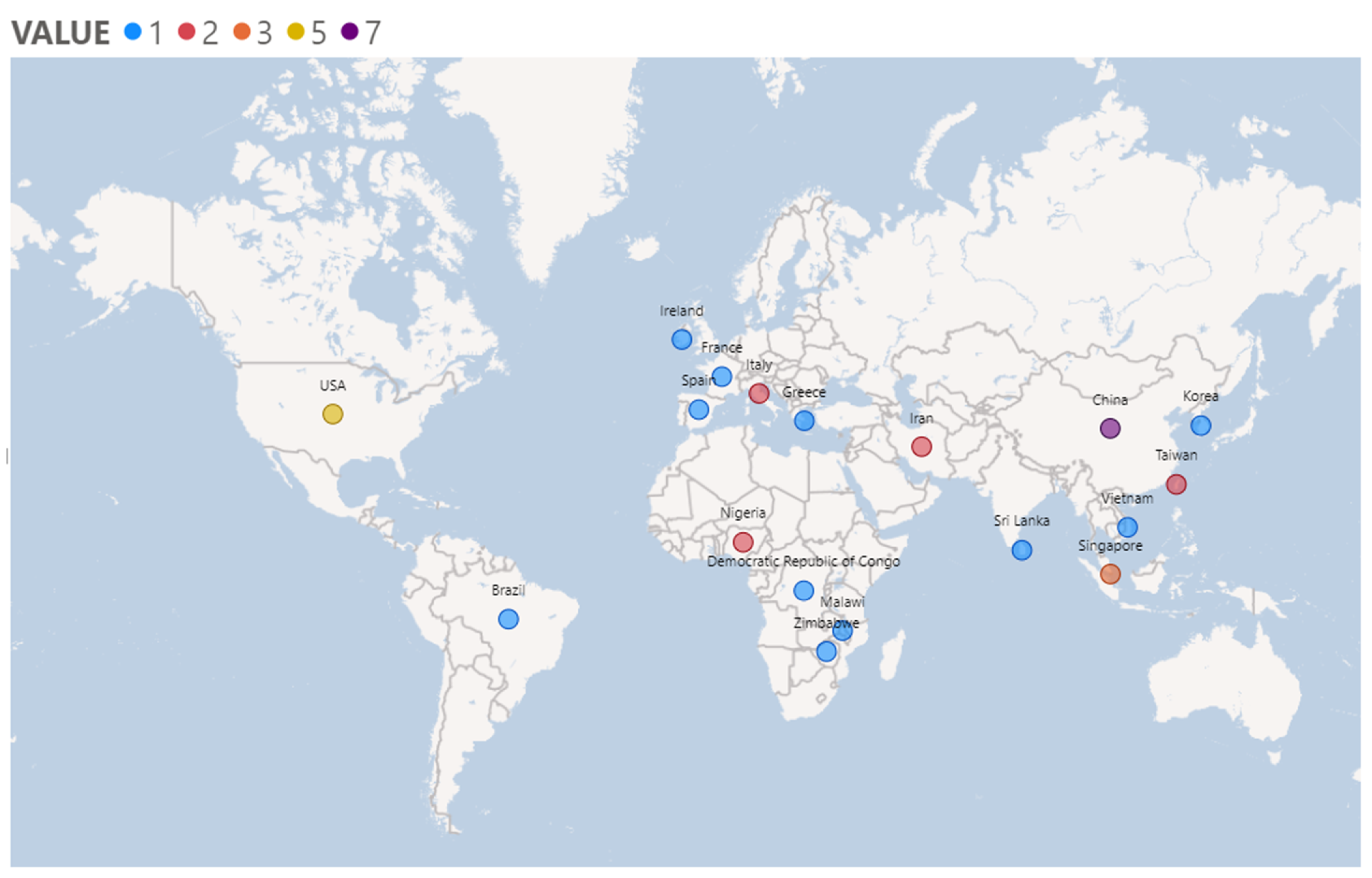

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Characteristics of Participants

3.4. Measurement Scales for Burden

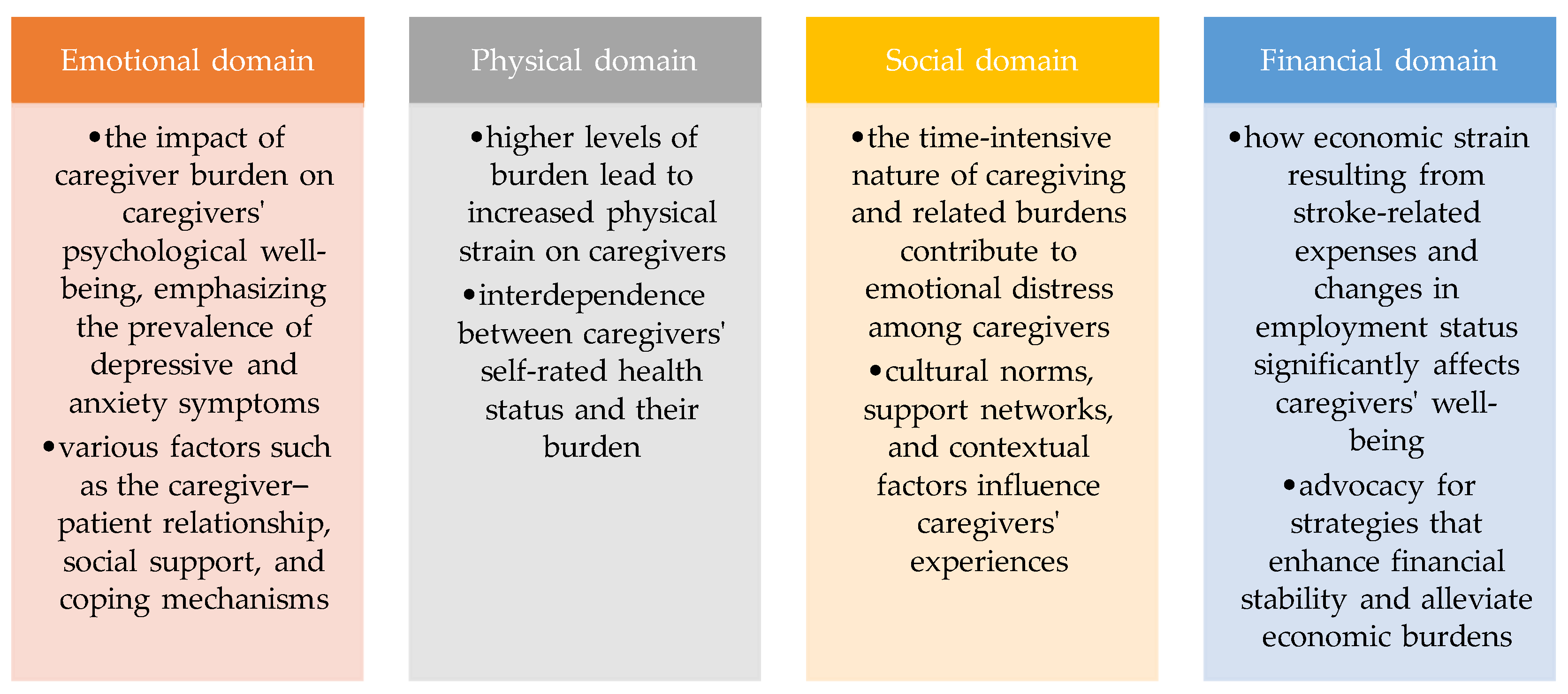

3.5. Domains of Burden Expression

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Caregiver Burden on Physical Health among Stroke Caregivers

4.2. The Impact of Burden on Social Functioning in Stroke Caregivers

4.3. The Impact of Burden on Financial Issues in Stroke Caregivers

4.4. The Impact of Caregiver Burden on the Psychological Health among Stroke Caregivers

4.5. Mechanisms Addressing Caregivers’ Burden

4.6. The Concept of the Caregiver

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Future Pespectives: Enhancing Caregiver Well-Being

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e67–e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R. Recovery from stroke: Current concepts and future perspectives. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkotis, C.; Giarmatzis, G.; Giannakou, E.; Moustakidis, S.; Tsatalas, T.; Tsiptsios, D.; Vadikolias, K.; Aggelousis, N. An Explainable Machine Learning Pipeline for Stroke Prediction on Imbalanced Data. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (Ed.) World Population Ageing 2007; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-92-1-151432-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenhoven, S.E.; Kirkevold, M.; Engedal, K.; Biong, S.; Kim, H.S. The lived experience of stroke survivors with early depressive symptoms: A longitudinal perspective. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2011, 6, 8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battersby, M.; Hoffmann, S.; Cadilhac, D.; Osborne, R.; Lalor, E.; Lindley, R. ‘Getting your Life Back on Track after Stroke’: A Phase II Multi-Centered, Single-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Stroke Self-Management Program Vs. the Stanford Chronic Condition Self-Management Program or Standard Care in Stroke Survivors. Int. J. Stroke 2009, 4, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragstad, L.K.; Kirkevold, M.; Foss, C. The indispensable intermediaries: A qualitative study of informal caregivers’ struggle to achieve influence at and after hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, M.; Vairale, J.; Gawali, K.; Dalal, P.M. Factors affecting burden on caregivers of stroke survivors: Population-based study in Mumbai (India). Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2012, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, T.F.; Costa, K.N.d.F.M.; Martins, K.P.; Fernandes, M.d.G.d.M.; Brito, S.d.S. Burden over family caregivers of elderly people with stroke. Esc. Anna Nery 2015, 19, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, B.J.; Young, M.E. Rethinking Intervention Strategies in Stroke Family Caregiving. Rehabil. Nurs. 2010, 35, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L.; Middleton, S. An investigation of family carers’ needs following stroke survivors’ discharge from acute hospital care in Australia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N.; Habibi, R.; Mackenzie, A. Respite: Carers’ experiences and perceptions of respite at home. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, W.E.; Roth, D.L.; Hovater, M.; Clay, O.J. Long-term impact of stroke on family caregiver well-being: A Popula-tion-Based Case-Control Study. Neurology 2015, 84, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.Z.; Tan, J.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms Among Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLennon, S.M.; Bakas, T.; Jessup, N.M.; Habermann, B.; Weaver, M.T. Task Difficulty and Life Changes Among Stroke Family Caregivers: Relationship to Depressive Symptoms. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 2484–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Chei, C.-L.; Menon, E.; Chow, W.L.; Quah, S.; Chan, A.; Matchar, D.B. Short-Term Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms in Stroke Survivors and Their Family Caregivers. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, E.; Evans, L.; Sommers, M.; Tkacs, N.; Riegel, B. Depressive symptoms in caregivers immediately after stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, C.C.; Costa, J.D.; Da Cruz, D.M.C. Burden and Quality of Life of Family Caregivers of Stroke Patients. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2018, 32, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youman, P.; Wilson, K.; Harraf, F.; Kalra, L. The Economic Burden of Stroke in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics 2003, 21 (Suppl. 1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, Z.K.; Temel, M. Burden of Caregiving for Stroke Patients and The Role of Social Support Among Family Members: An Assessment Through Home Visits. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 10, 1696. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J. Meta-Anal. 2017, 5, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, E.C.; Okoro, S.C.; Akosile, C.O.; Onwuakagba, I.U.; Ihegihu, E.Y.; Ihegihu, C.C. Informal caregivers’ well-being and care recipients’ quality of life and community reintegration—Findings from a stroke survivor sample. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.X.; Pinyopasakul, W.; Pongthavornkamol, K.; Panitrat, R. Factors predicting the health status of caregivers of stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, Y. Determinants of caregiver burden of patients with haemorrhagic stroke in China. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, e12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Yang, Q.; Kong, L.; Hu, L.; Zeng, L. Relationship between the anxiety/depression and care burden of the major caregiver of stroke patients. Medicine 2018, 97, e12638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Lee, C.S.; Lyons, K.S.; Simeone, S.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Quality of Life Trajectories Among Stroke Survivors and the Related Changes in Caregiver Outcomes: A Growth Mixture Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 109, 433–440.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthucumarana, M.W.; Samarasinghe, K.; Elgán, C. Caring for stroke survivors: Experiences of family caregivers in Sri Lanka—A qualitative study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2018, 25, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-H.; Lou, M.-F.; Feng, T.-H.; Chu, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-J.; Liu, H.-E. Mediating effects of burden on quality of life for caregivers of first-time stroke patients discharged from the hospital within one year. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akosile, C.O.; Banjo, T.O.; Okoye, E.C.; Ibikunle, P.O.; Odole, A.C. Informal caregiving burden and perceived social support in an acute stroke care facility. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregosa, M.B.; Sada, R.; Perez, I. Dealing with stroke: Perspectives from stroke survivors and stroke caregivers from an underserved Hispanic community. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Wilson, S.; Lin, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Benefit finding for Chinese family caregivers of community-dwelling stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e1419–e1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.-M.; Huang, L.-L.; Dou, J.; Wang, X.-X.; Wang, P.-X. Post-stroke depression as a predictor of caregivers burden of acute ischemic stroke patients in China. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.-L.; Tang, Y.-F.; Xia, Y.-Q.; Wei, J.-H.; Li, G.-R.; Mu, X.-M.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Jin, Q.-Z.; He, M.; Cui, L.-J. A survey of caregiver burden for stroke survivors in non-teaching hospitals in Western China. Medicine 2022, 101, e31153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-S.; Fan, C.-W.; Hsieh, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Burdens on caregivers of patients with stroke during a pandemic: Relationships with support satisfaction, psychological distress, and fear of COVID-19. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavga, A.; Kalemikerakis, I.; Faros, A.; Milaka, M.; Tsekoura, D.; Skoulatou, M.; Tsatsou, I.; Govina, O. The Effects of Patients’ and Caregivers’ Characteristics on the Burden of Families Caring for Stroke Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, A.; Azimian, J.; Mafi, M.; Allen, K.-A.; Motalebi, S.A. Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of older patients with stroke. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Tsang, W.N.; Yang, S.C.; Kwok, J.Y.Y.; Lou, V.W.; Lau, K.K. Qualitative Study of Chinese Stroke Caregivers’ Caregiving Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Stroke 2021, 52, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, M.A.; Bahloli, S.; JamshidiOrak, R.; Ghaffari, F. Investigating the needs of family caregivers of older stroke patients: A longitudinal study in Iran. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achilike, S.; Beauchamp, J.E.S.; Cron, S.G.; Okpala, M.; Payen, S.S.; Baldridge, L.; Okpala, N.; Montiel, T.C.; Varughese, T.; Love, M.; et al. Caregiver Burden and Associated Factors Among Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2020, 52, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barral, M.; Rabier, H.; Termoz, A.; Serrier, H.; Colin, C.; Haesebaert, J.; Derex, L.; Nighoghossian, N.; Schott, A.; Viprey, M.; et al. Patients’ productivity losses and informal care costs related to ischemic stroke: A French population-based study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, C.; La Face, A.; Buono, V.L.; Di Cara, M.; Micchìa, K.; Bonanno, L.; Logiudice, A.L.; Todaro, A.; Palmeri, R.; Bramanti, P.; et al. Factors related to cognitive reserve among caregivers of severe acquired brain injury. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 77, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.J.; Lyons, K.S.; Schellinger, J.; Stapleton, K.; Bakas, T. Interpersonal relationship challenges among stroke survivors and family caregivers. Soc. Work. Health Care 2020, 59, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalavina, R. The challenges and experiences of stroke patients and their spouses in Blantyre, Malawi. Malawi Med. J. 2019, 31, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marima, P.; Gunduza, R.; Machando, D.; Dambi, J.M. Correlates of social support on report of probable common mental disorders in Zimbabwean informal caregivers of patients with stroke: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Skidmore, E.R.; Rodakowski, J. Relationship Consensus and Caregiver Burden in Adults with Cognitive Impairments 6 Months Following Stroke. PM&R 2019, 11, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.S.; Subramaniam, M.; Matchar, D.B.; Hong, S.-I.; Koh, G.C.-H. The associations between caregivers’ psychosocial characteristics and caregivers’ depressive symptoms in stroke settings: A cohort study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Kitoko, G.M.; Vivalya, B.M.N.; Vagheni, M.M.; Nzuzi, T.M.M.; Lusambulu, S.M.; Lelo, G.M.; Mpembi, M.N.; Miezi, S.M.M. Psychological Burden in Stroke Survivors and Caregivers Dyads at the Rehabilitation Center of Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo): A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tyagi, S.; Hoenig, H.; Lee, K.E.; Venketasubramanian, N.; Menon, E.; De Silva, D.A.; Yap, P.; Tan, B.Y.; Young, S.H.; et al. Burden of informal care in stroke survivors and its determinants: A prospective observational study in an Asian setting. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.L.P.; Lee, S.J.; Son, Y.-J.P.; Miller, J.L.; King, R.B.P. Depressive Symptom Trajectories in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors During First Year of Caregiving. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 36, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freytes, I.M.; Sullivan, M.; Schmitzberger, M.; LeLaurin, J.; Orozco, T.; Eliazar-Macke, N.; Uphold, C. Types of stroke-related deficits and their impact on family caregiver’s depressive symptoms, burden, and quality of life. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.-X.; Lin, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, D.-B.; Wang, S.-S.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Cheung, D.S.K. Benefits finding among Chinese family caregivers of stroke survivors: A qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, D.; Gaynor, E.; Large, M.; Conway, O.; Bennett, K.; Williams, D.J.; Callaly, E.; Dolan, E.; Hickey, A. Stroke survivor cognitive decline and psychological wellbeing of family caregivers five years post-stroke: A cross-sectional analysis. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, R.; Chei, C.-L.; Menon, E.B.; Chow, W.-L.; Quah, S.; Chan, A.; Ajay, S.; Matchar, D.B. Trajectories of positive aspects of caregiving among family caregivers of stroke-survivors: The differential impact of stroke-survivor disability. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2018, 25, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva-Moreno, J.; Peña-Longobardo, L.M.; Mar, J.; Masjuan, J.; Soulard, S.; Gonzalez-Rojas, N.; Becerra, V.; Casado, M.; Torres, C.; Yebenes, M.; et al. Determinants of Informal Care, Burden, and Risk of Burnout in Caregivers of Stroke Survivors the CONOCES Study. Stroke 2018, 49, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Lin, B.; Li, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Z. Effects of modified 8-week reminiscence therapy on the older spouse caregivers of stroke survivors in Chinese communities: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseung, V.; Jaglal, S.; Salbach, N.M.; I Cameron, J. A Qualitative study assessing organisational readiness to implement caregiver support programmes in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“stroke” AND “caregivers” AND “burden”) |

| Scopus | (“stroke” AND “caregivers” AND “burden”) |

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Exposed Cohort | Non-Exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Outcome of Interest | Study Controls (a) | Study Controls (b) | Assessment of Outcome | Length of Follow-Up | Adequacy of Follow-Up |

| Okoye et al., 2019 [24] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Long et al., 2019 [25] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Zhu et al., 2019 [26] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Hu et al., 2018 [27] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Pucciarelli et al., 2019 [28] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Wagachchige Muthucumarana et al., 2018 [29] | - | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Tsai et al., 2018 [30] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Akosile et al., 2018 [31] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Caro et al., 2018 [19] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Torregosa et al., 2018 [32] | - | - | - | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Mei et al., 2018 [33] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Dou et al., 2018 [34] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Cao et al., 2022 [35] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Liu et al., 2022 [36] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Kavga et al., 2021 [37] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Kazemi et al., 2021 [38] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Lee et al., 2021 [39] | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Farahani et al., 2020 [40] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Achilike et al., 2020 [41] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Barral et al., 2021 [42] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Formica et al., 2020 [43] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| McCarthy et al., 2020 [44] | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Kalavina et al., 2019 [45] | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Marima et al., 2019 [46] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Wu et al., 2019 [47] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Koh et al., 2022 [48] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Kitoko et al., 2022 [49] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Wang et al., 2021 [50] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Chung et al., 2021 [51] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Freytes et al., 2021 [52] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Mei et al., 2020 [53] | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | - | - | - |

| Rohde et al., 2019 [54] | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - |

| Malhotra et al., 2018 [55] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Oliva-Moreno et al., 2018 [56] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| First Author (Year) | Title | Type of Research (Quantitative—Qualitative) | N (Caregivers) | Time after Stroke | Type of Caregiver (Formal—Informal) | Caregiver Characteristics (Stay at Home or Not, Hours Spent with SS, etc.) | Measurement Scales for Burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okoye et al., 2019 [24] | Informal caregivers’ well-being and care recipients’ quality of life and community reintegration—findings from a stroke survivor sample | Quantitative | 82 (31 M/51 F) Mean age = 36.13 ± 13.69 | At least 1 month post-discharge 1–102 months average months = 15.32 ± 15.96 | Informal 28—spouse 37—child 13—siblings and others 4—paid |

| Caregivers Strain Index (CSI) |

| Long et al., 2019 [25] | Factors predicting the health status of caregivers of stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study | Mixed methods | 126 (36 M/90 F) Mean age = 52.4 ± 8.8 | At least 1 month post-stroke | Informal 71—spouse 44—child 11—other (parent, grandchild, sibling) |

|

|

| Zhu et al., 2019 [26] | Determinants of caregiver burden of patients with haemorrhagic stroke in China | Mixed methods | 202 (114 M/88 F)

| T1–T2–T3 T1: 1–2 before discharge T2: 3 months post-discharge T3: 6 months post-discharge | Informal | Living together:

| Bakas Caregiving Outcome Scale (BCOS) |

| Hu et al., 2018 [27] | Relationship between the anxiety/depression and care burden of the major caregiver of stroke patients | Quantitative | 117 (45 M/72 F) Mean age = 56.66 ± 9.62 | N/A | Informal 76—spouse 35—child 6—other relatives | Care time:

|

|

| Pucciarelli et al., 2019 [28] | Quality of Life Trajectories Among Stroke Survivors and the Related Changes in Caregiver Outcomes: A Growth Mixture Study | Quantitative | 244 (34.8% M/65.2% F) Mean age = 52.7 | T0: predischarge T1: 3 months post-stroke T2: 6 months post-stroke T3: 9 months post-stroke T4: 12 months post-stroke | Informal |

|

|

| Wagachchige Muthucumarana et al., 2018 [29] | Caring for stroke survivors: experiences of family caregivers in Sri Lanka—a qualitative study | Qualitative | 10 (2 M/8 F) Age range = 33–69 Mean age = 51 | Within a month | Informal 6—wife 2—son 1—daughter 1—daughter-in-law | Duration of experience as the family caregiver:

Financial assistance: Y = 0/N = 10 | Interviews Open-ended questions |

| Tsai et al., 2018 [30] | Mediating effects of burden on quality of life for caregivers of first-time stroke patients discharged from the hospital within one year | Quantitative | 126 Mean age = 49 ± 13.2 Range = 20–81 | Within a year Mean time since stroke = 154.8 days ± 88.8 Range = 4–315 days | Informal 44.4%—child 42.1%—spouse |

23—hired a non-family caregiver Financial assistance—Payer for medical fees 46—the patients themselves 66—their children 10—their spouse 4—other | Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) |

| Akosile et al., 2018 [31] | Informal caregiving burden and perceived social support in an acute stroke care facility | Quantitative | 56 (21 M/35 F) Mean age = 28.2 ± 9.5 | In acute phase | Informal | N/A |

|

| Caro et al., 2018 [19] | Burden and quality of life of family caregivers of stroke patients | Quantitative | 30 (3 M/27 F) Mean age = 58.70 ± 13.34 | Within a year | Informal 17—wife 7—child 2—mother 4—other | Living together: Y = 26/N = 4 | Zarit Burden Interview Scale (ZBIS) |

| Torregosa et al., 2018 [32] | Dealing with stroke: Perspectives from stroke survivors and stroke caregivers from an underserved Hispanic community | Qualitative | 8 Mean age = 53.25 | N/A | Informal 6—wife or child 2—mother or sister | Living together: Y = 8/N = 0 | Semi-structured interviews |

| Mei et al., 2018 [33] | Benefit finding for Chinese family caregivers of community-dwelling stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. | Quantitative | 145 (43 M/102 F) Mean age = 50.38 ± 13.29 | N/A | Informal 52—spouse 73—child 15—parent 5—other | Caregiving hours per day: <8: 26 9–12: 27 >12: 92 | Chinese Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) |

| Dou et al., 2018 [34] | Post-stroke depression as a predictor of caregivers burden of acute ischemic stroke patients in China. | Quantitative | 271 (109 M/162 F) Mean age = 48.4 ± 14.7 | In hospital | Informal 115—spouse 131—child 25—other members | primary caregiver | Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (ZCBI) |

| Cao et al., 2022 [35] | A survey of caregiver burden for stroke survivors in non-teaching hospitals in Western China | Quantitative | 328 mean age = 64.9 (13.4) | In hospital | Informal | primary caregiver | Zarit Burden Interview Scale (ZBIS), Social support Rating Scale (SSRS), General Self Efficacy Scale (GSES) |

| Liu et al., 2022 [36] | Burdens on caregivers of patients with stroke during a pandemic: relationships with support satisfaction, psychological distress, and fear of COVID-19 | Quantitative | 171 | In hospital | Informal | N/A | Zarit Burden Interview Scale, Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS-21), satisfaction of support survey, and Fear of COVID-19 Scale. |

| Kavga et al., 2021 [37] | The Effects of Patients’ and Caregivers’ Characteristics on the Burden of Families Caring for Stroke Survivors | Quantitative | 109 stroke patients mean age 69.3 (13.7), 109 primary caregivers mean age 58.0 (13.5) | 4 months since the stroke occurred | informal | to have the main responsibility for patient care, and to be living with the patient. | Barthel Index, the caregiving outcome (revised Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale), the caregiver’s mental state (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression, CES-D), the level of social support (Personal Resource Questionnaire, PRQ 2000) |

| Kazemi et al., 2021 [38] | Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of older patients with stroke | Quantitative | 110 mean age = 32.09 ± 8.70 | N/A | Informal | principal caregiver for a minimum of 1 month, not being paid for the care provided, and having a family relationship with the older patient. | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), Lazarus coping strategies questionnaires, and demographic checklists |

| Lee et al., 2021 [39] | Qualitative Study of Chinese Stroke Caregivers’ Caregiving Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic | Qualitative | 25 mean age 55.96 (11.28) | N/A | Informal |

|

|

| Farahani et al., 2020 [40] | Investigating the needs of family caregivers of older stroke patients: a longitudinal study in Iran | Quantitative | 210 mean age 42.8 ± 11.79 | In hospital | Informal |

|

|

| Achilike et al., 2020 [41] | Caregiver Burden and Associated Factors Among Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors | Quantitative | 88 mean age 54.33 ±13.65 | within 2 years | Informal |

| Zarit Burden Interview, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Barthel Index. |

| Barral et al., 2021 [42] | Patients’ productivity losses and informal care costs related to ischemic stroke: a French population-based study | Qualitative | 108 (40 M/68 F), mean age 59.5 ± 15.9 | 1 year post-stroke | Informal 66—spouse 31—children 2—sibling 2—in-laws 7—other | Staying together: 80—Y/28—N | Self-reported questionnaires—IC Telephone interview |

| Formica et al., 2020 [43] | Factors related to cognitive reserve among caregivers of severe acquired brain injury | Quantitative | 29 | In hospital | Informal | N/A |

|

| McCarthy et al., 2020 [44] | Interpersonal relationship challenges among stroke survivors and family caregivers | Qualitative | 19 care dyads, mean age = 55.61 | Within 12 months of stroke | Informal | having experience with stroke and being in a committed care partnership, as well as by dyad type, living together in the community or spending a “significant amount of time together in care-related activities” | semi-structured interview guide (The Systemic-Transactional Model of Stress and Coping and the Developmental-Contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Illness) |

| Kalavina et al., 2019 [45] | The challenges and experiences of stroke patients and their spouses in Blantyre, Malawi | Qualitative | 18 (nine dyads of patients with stroke and spouses) | Sub-acute, chronic | Informal | marriage (only married couples who were living together at the time the stroke occurred were recruited | Semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus group discussions |

| Marima et al., 2019 [46] | Correlates of social support on report of probable common mental disorders in Zimbabwean informal caregivers of patients with stroke: a cross-sectional survey | Quantitative | 71 mean age = 41.5 (13.8) | Acute, sub-acute | Informal | primary, unpaid caregivers |

|

| Wu et al., 2019 [47] | Relationship Consensus and Caregiver Burden in Adults with Cognitive Impairments 6 Months Following Stroke | Quantitative | 60 dyads caregiver age: 59.18 (10.45), care recipient age: 65.87 (13.23) | N/A | Informal [spouses (58.3%) or children (23.3%)] | lived with care recipients |

|

| Koh et al., 2022 [48] | The associations between caregivers’ psychosocial characteristics and caregivers’ depressive symptoms in stroke settings: a cohort study | Quantitative | 214 | Acute phase | informal | caregiver that remained during the first year after stroke |

|

| Kitoko et al., 2022 [49] | Psychological Burden in Stroke Survivors and Caregivers Dyads at the Rehabilitation Center of Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo): A Cross-Sectional Study | quantitative | 85 (27 M/58 F) Mean age = 42.3 ± 14.34 | In rehabilitation centre | N/A | N/A | Zarit Burden Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| Wang et al., 2021 [50] | Burden of informal care in stroke survivors and its determinants: a prospective observational study in an Asian setting | Quantitative | 661 | They used a dataset from a prospective cohort study | Informal | N/A |

|

| Chung et al., 2021 [51] | Depressive Symptom Trajectories in Family Caregivers of stroke Survivors during first year of caregiving | quantitative | 102 (35 M/67 F) Mean age = 58 ± 13.3 | T0 = acute rehabilitation hospitalization T1 = 6–10 weeks post-discharge T2 = 1 year post-discharge T3 = 2 years post-discharge | Informal 94—spouse 8—other | They were living with the patient |

|

| Freytes et al., 2021 [52] | Types of stroke-related deficits and their impact on family caregiver’s depressive symptoms, burden and quality of life | Quantitative | n = 109 | N/A | Informal | Females, living together with stroke survivors, |

|

| Mei et al., 2020 [53] | Benefits finding among Chinese family caregivers of stroke survivors: A qualitative descriptive study | Qualitative | 20 (12 M/8 F) mean age = 58.6 | N/A | Informal | Living together | Audio-recorded interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, with an average of approximately 42 min. Six main themes and 14 subthemes |

| Rohde et al., 2019 [54] | Stroke survivor cognitive decline and psychological wellbeing of family caregivers five years post-stroke: a cross-sectional analysis | qualitative | 78 | (1) after 6 months (2) after 5 years | Informal | Family members only living with stroke survivors |

|

| Malhotra et al., 2018 [55] | Trajectories of positive aspects of caregiving among family caregivers of stroke -survivors: the differential impact of stroke survivor disability | Quantitative | 173 (38.2% M/61.8 F) mean age: 50 ± 12.2 | 6–8 months after stroke—3 Interviews | Informal | Family members |

|

| Oliva-Moreno et al., 2018 [56] | Determinants of informal care, burden and risk of burnout in caregivers of stroke survivors the CONOCES Study. | Quantitative | 3 months post-stroke: 224 mean age 55.2 12 months post-stroke: 202 mean age, 56.3 | 3 and 12 months post-stroke | Informal | Living at home, Female 70.5%–>3 months, |

|

| First Author (Year) | Title | Emotional Domain | Physical Domain | Social Domain | Financial Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okoye et al., 2019 [24] | Informal caregivers’ well-being and care recipients’ quality of life and community reintegration—findings from a stroke survivor sample |

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Long et al., 2019 [25] | Factors predicting the health status of caregivers of stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study | In relation to mental health, the low scores were present in all sub-scales, including social functioning, vitality, role-emotional, and general mental health. | Caregiver burden was the strongest predictor, which explained 70.3% of variations in health status of caregivers of stroke survivors. | It is possible that the lower scores on the mental health dimension could be related to the high level of perceived caregiver burden, which involves the emotional, social, and well-being status of these caregivers. | N/A |

| Zhu et al., 2019 [26] | Determinants of caregiver burden of patients with haemorrhagic stroke in China | The caregiver burden decreased over time

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hu et al., 2018 [27] | Relationship between the anxiety/depression and care burden of the major caregiver of stroke patients |

| The length of care time was positively correlated with the anxiety and depression scores. | N/A | The economic burden caused by the disease is an important influencing factor of the caregiver anxiety and depression. |

| Pucciarelli et al., 2019 [28] | Quality of Life Trajectories Among Stroke Survivors and the Related Changes in Caregiver Outcomes: A Growth Mixture Study |

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wagachchige Muthucumarana et al., 2018 [29] | Caring for stroke survivors: experiences of family caregivers in Sri Lanka—a qualitative study | Some of the family caregivers were looking after their small children together with the stroke survivor, which caused them to feel overburdened. | Some caregivers were experiencing physical problems such as back, leg, and neck pain, high BP, and tiredness. They were missing the freedom to rest or sleep sufficiently. | The caregivers’ workload was increased due to their role. Family caregivers felt more homebound, and missed attending even the most common social gatherings. | Many caregivers became dependent on other family members, relatives, neighbours, friends for support, finances or meals when the family income was affected. |

| Tsai et al., 2018 [30] | Mediating effects of burden on quality of life for caregivers of first-time stroke patients discharged from the hospital within one year | Caregiver burden and family resources were significant predictors of caregiver QoL. The higher the CSI score, the lower the caregiver’s QoL | The subscales in the physical and social domains had similar scores | N/A | The lowest CSI score was in the financial domain |

| Akosile et al., 2018 [31] | Informal caregiving burden and perceived social support in an acute stroke care facility | N/A | N/A | No significant association was found between the patient socio-demographics and burden. Participants’ score on the family domain of the social support scale was the only domain with a significant correlation with their scores on the burden scale. | N/A |

| Caro et al., 2018 [19] | Burden and quality of life of family caregivers of stroke patients | Moderate levels of burden were associated with increased scores for risk of depression and changes in emotional health. Other possible factors that trigger stress could be social isolation, relationship problems with SS, feelings of self-annulment. | A high prevalence of chronic conditions and psychosomatic problems were reported. Predominantly body aches, and psychiatric problems. The most frequent health problem reported was back pain, which may be associated with depression and sleep disorders. | The reduction in sleep and leisure time may have health consequences and result in social isolation, as well as reducing active involvement in other activities, with further detrimental health consequences and increased burden on the caregivers. | N/A |

| Torregosa et al., 2018 [32] | Dealing with stroke: Perspectives from stroke survivors and stroke caregivers from an underserved Hispanic community | Caregiving brought conflicting emotions to caregivers. Constant worry, hypervigilance, multitasking. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mei et al., 2018 [33] | Benefit finding for Chinese family caregivers of community-dwelling stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. | Benefit-finding mediated the relationships between caregiver burden, anxiety, and depression, but it did not represent a moderating role in the relationship between caregiver burden, anxiety, and depression. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dou et al., 2018 [34] | Post-stroke depression as a predictor of caregivers’ burden of acute ischemic stroke patients in China. | Post- stroke depression was modestly associated with caregiver burden of acute ischemic patients. | Female gender and normal muscle strength were the predictive factors for caregiver burden. | N/A | N/A |

| Cao et al., 2022 [35] | A survey of caregiver burden for stroke survivors in non-teaching hospitals in Western China | The more severe the condition, the heavier the caregiver burden | N/A | Only 27.4% of caregivers received adequate social support, while only 20.7% of caregivers had high levels of self-efficacy. | The type of health insurance has no impact on reducing the burden of caregivers |

| Liu et al., 2022 [36] | Burdens on caregivers of patients with stroke during a pandemic: relationships with support satisfaction, psychological distress, and fear of COVID-19 | The caregiver burden was negatively correlated with satisfaction with family support, but positively with psychological distress and the fear of COVID-19. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kavga et al., 2021 [37] | The Effects of Patients’ and Caregivers’ Characteristics on the Burden of Families Caring for Stroke Survivors | The severity of the caregivers’ burden correlated positively with the severity of depression, and higher depressive symptoms were related to life changes for the worse | The caregivers’ perception of burden was lower for those caregivers in good health, but higher for those who provided many months and daily hours of care. | A significant correlation between social support and caregivers’ burden score was found | N/A |

| Kazemi et al., 2021 [38] | Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of older patients with stroke | The care burden reported by the majority of caregivers of stroke survivors was mild to moderate | N/A | N/A | |

| Lee et al., 2021 [39] | Qualitative Study of Chinese Stroke Caregivers’ Caregiving Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic | Increased psychological and emotional burden was detected | Physical burden, increased risk and frequency of abuse were unveiled. | N/A | N/A |

| Farahani et al., 2020 [40] | Investigating the needs of family caregivers of older stroke patients: a longitudinal study in Iran | N/A | N/A | Needs under the dimensions of “professional support” and “health information” were identified | N/A |

| Achilike et al., 2020 [41] | Caregiver Burden and Associated Factors Among Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors | Depressive symptoms were highly correlated with caregiver burden | Physical health was associated with caregiver health issues, stroke type, anxiety, and depression, and mental health was associated with caregiver health issues | N/A | N/A |

| Barral et al., 2021 [42] | Patients’ productivity losses and informal care costs related to ischemic stroke: a French population-based study | N/A | N/A | N/A | IC and productivity losses of patients with IS during the first year represent a significant economic burden for society compared to direct costs. |

| Formica et al., 2020 [43] | Factors related to cognitive reserve among caregivers of severe acquired brain injury |

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| McCarthy et al., 2020 [44] | Interpersonal relationship challenges among stroke survivors and family caregivers | N/A | N/A | Social workers may have the opportunity to assist dyads with disrupting negative communication cycles, strengthening empathy and collaboration, and achieving a balance so that each person’s needs are met. | N/A |

| Kalavina et al., 2019 [45] | The challenges and experiences of stroke patients and their spouses in Blantyre, Malawi | Caregiving was most difficult when the patients had faced incontinence, speech impairment and problems with anger management | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Marima et al., 2019 [46] | Correlates of social support on report of probable common mental disorders in Zimbabwean informal caregivers of patients with stroke: a cross-sectional survey | Informal caregivers of patients with stroke were at risk of common mental disorders | Symptoms of insomnia, feeling overwhelmed, thinking too deeply and feeling run down | Caregivers who received an adequate amount of social support were likely to exhibit better mental health | Only 18.3% of carers reported adequate finances, and having lower income was associated with greater risk of psychiatric morbidity |

| Wu et al., 2019 [47] | Relationship Consensus and Caregiver Burden in Adults with Cognitive Impairments 6 Months Following Stroke | N/A | N/A | An enhancement of relationship consensus and satisfaction may potentially reduce burden and risk of adverse health outcomes in caregivers. | N/A |

| Koh et al., 2022 [48] | The associations between caregivers’ psychosocial characteristics and caregivers’ depressive symptoms in stroke settings: a cohort study | The study identified subjective burden, quality of care relationship and expressive social support as significantly associated with caregivers’ depressive symptoms | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kitoko et al., 2022 [49] | Psychological Burden in Stroke Survivors and Caregivers Dyads at the Rehabilitation Center of Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo): A Cross-Sectional Study | The majority of stroke survivors and caregivers dyads had a burden of depression ranging from mild to moderate. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wang et al., 2021 [50] | Burden of informal care in stroke survivors and its determinants: a prospective observational study in an Asian setting | Informal care burden remains high up to 12 months post-stroke. Factors such as functional dependency, stroke severity, informal caregiver gender and co-caring with foreign domestic workers were associated with informal care burden. | |||

| Chung et al., 2021 [51] | Depressive Symptom Trajectories in Family Caregivers of stroke Survivors during first year of caregiving |

| Caregivers have worsened perceived health during the first year of caregiving. In addition, we identified that caregivers with persistent depressive symptoms were the most vulnerable caregivers at risk of having poor health status after the first year of caregiving. Caregivers with high caregiving requirements are less likely to have adequate rest, find time for exercise, and have enough rest when sick. | Caregivers with persistent depressive symptoms were characterized by having the lowest levels of perceived availability of social support, and the unhealthiest level of general family function | N/A |

| Freytes et al., 2021 [52] | Types of stroke related deficits and their impact on family caregiver’s depressive symptoms, burden and quality of life | The Cognitive/Emotional deficits appear to impact caregiver well-being more than the Motor/Functional deficits. | The motor/functional deficits failed to significantly predict any of the caregiver outcomes | N/A | N/A |

| Mei et al., 2020 [53] | Benefits finding among Chinese family caregivers of stroke survivors: A qualitative descriptive study | Internal benefits: increases in knowledge and skills, the development of positive attitudes, and the development of a sense of worthiness and achievement | N/A | External benefits: family growth and gains in social support | N/A |

| Rohde et al., 2019 [54] | Stroke survivor cognitive decline and psychological wellbeing of family caregivers five years post -stroke: a cross-sectional analysis | Significantly increased levels of family member anxious and depressive symptoms were associated with stroke survivor cognitive decline | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malhotra et al., 2018 [55] | Trajectories of positive aspects of caregiving among family caregivers of stroke -survivors: the differential impact of stroke survivor disability | Increase in stroke-survivor disability was associated with a significant downward shift (reduction in positive aspects of caregiving) of the Persistently Low trajectory and a significant upward shift (increase in positive aspects of caregiving) of the Persistently High trajectory. | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Oliva-Moreno et al., 2018 [56] | Determinants of informal care, burden and risk of burnout in caregivers of stroke survivors the CONOCES Study. |

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tziaka, E.; Tsiakiri, A.; Vlotinou, P.; Christidi, F.; Tsiptsios, D.; Aggelousis, N.; Vadikolias, K.; Serdari, A. A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050565

Tziaka E, Tsiakiri A, Vlotinou P, Christidi F, Tsiptsios D, Aggelousis N, Vadikolias K, Serdari A. A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(5):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050565

Chicago/Turabian StyleTziaka, Eftychia, Anna Tsiakiri, Pinelopi Vlotinou, Foteini Christidi, Dimitrios Tsiptsios, Nikolaos Aggelousis, Konstantinos Vadikolias, and Aspasia Serdari. 2024. "A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 12, no. 5: 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050565

APA StyleTziaka, E., Tsiakiri, A., Vlotinou, P., Christidi, F., Tsiptsios, D., Aggelousis, N., Vadikolias, K., & Serdari, A. (2024). A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 12(5), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050565