Dermatology Self-Medication in Nursing Students and Professionals: A Multicentre Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

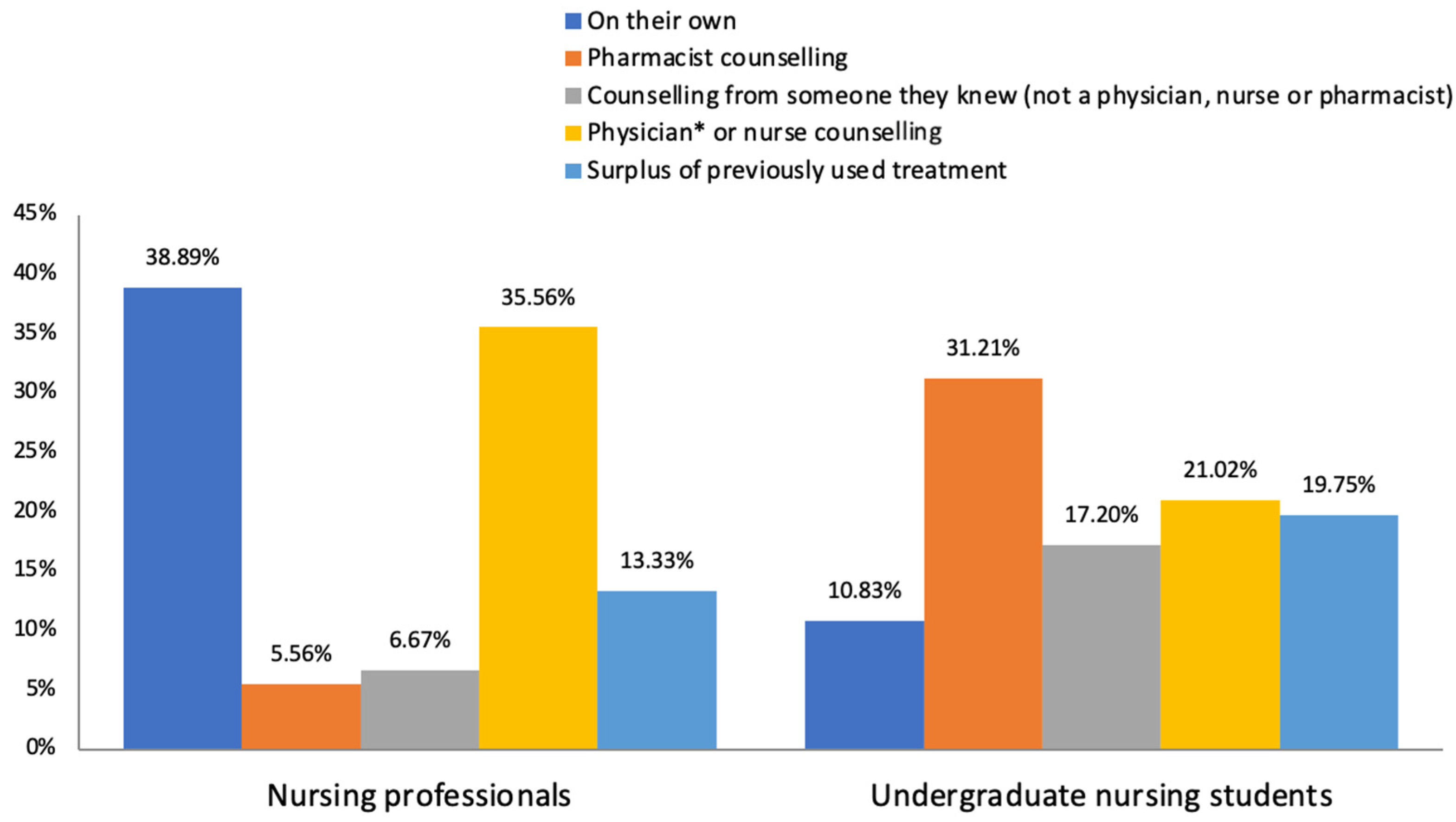

3.1. Self-Medication in Nurses

3.2. Self-Medication in Nursing Students

3.3. Influence of Age and Professional/Academic Career on Self-Medication in Nursing

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Conclusion and Practice Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO_EDM_QSM_00.1_eng.pdf. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66154/WHO_EDM_QSM_00.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Andrés, M.I.G.; Blanco, V.G.; Verdejo, I.C.; Guerra, J.A.I.; García, D.F. Self-Medication of Drugs in Nursing Students from Castile and Leon (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 18, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Borrajo Lama, C.; Arribas, A.A. Self medication in nursing. Rev. Enferm. Barc. Spain. 2004, 27, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa-Fissmer, M.; Mendonça, M.G.; Martins, A.H.; Galato, D. Prevalence of self-medication for skin diseases: A systematic review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calamusa, A.; Di Marzio, A.; Cristofani, R.; Arrighetti, P.; Santaniello, V.; Alfani, S.; Carducci, A. Factors that influence Italian consumers’ understanding of over-the-counter medicines and risk perception. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Loyola Filho, A.I.; Uchoa, E.; Guerra, H.L.; Firmo, J.O.A.; Lima-Costa, M.F. Prevalência e fatores associados à automedicação: Resultados do projeto Bambuí. Rev. Saúde Pública 2002, 36, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassa, T.; Gedif, T.; Andualem, T.; Aferu, T. Antibiotics self-medication practices among health care professionals in selected public hospitals of Addis Ababa. Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekadu, G.; Dugassa, D.; Negera, G.Z.; Woyessa, T.B.; Turi, E.; Tolossa, T.; Fetensa, G.; Assefa, L.; Getachew, M.; Shibiru, T. Self-Medication Practices and Associated Factors Among Health-Care Professionals in Selected Hospitals of Western Ethiopia, Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janatolmakan, M.; Abdi, A.; Andayeshgar, B.; Soroush, A.; Khatony, A. The Reasons for Self-Medication from the Perspective of Iranian Nursing Students: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 2960768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamata, V.V.; Gandhi, A.M.; Patel, P.P.; Desai, M.K. Self-medication for Acne among Undergraduate Medical Students. Indian J. Dermatol. 2017, 62, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, R.J.; Duhig, J.; Russell, A.; Scarazzini, L.; Lievano, F.; Wolf, M.S. Best-practices for the design and development of prescription medication information: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1351–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battyáni, Z. Dermatological treatment. Orv. Hetil. 2006, 147, 2475–2480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tameez-Ud-Din, A.; Malik, I.J.; Bhatti, A.A.; Din, A.T.U.; Sadiq, A.; Khan, M.T.; Chaudhary, N.A.; Arshad, D.; Knowledge, A.O. Attitude, and Practices Regarding Self-medication for Acne Among Medical Students. Cureus 2019, 11, e5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kombaté, K.; Técléssou, J.N.; Saka, B.; Akakpo, A.S.; Tchangai, K.O.; Mouhari-Toure, A.; Mahamadou, G.; Gnassingbé, W.; Abilogun-Chokki, A.; Pitché, P. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Self-Medication in Dermatology in Togo. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 7521831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sireci, S.; Faulkner-Bond, M. Validity evidence based on test content. Psicothema 2014, 26, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampieri, R.H.; Fernandez-Collado, C.F. Metodología de la Investigación, Sexta Edición; McGraw-Hill Education: Álvaro Obregón, México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, S.I.; Bugaighis, L.M.T.; Sharif, R.S. Self-Medication Practice among Pharmacists in UAE. Pharmacol. Amp Pharm. 2015, 6, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barros, A.R.R.; Griep, R.H.; Rotenberg, L. Self-medication among nursing workers from public hospitals. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2009, 17, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Jandani, R.; Al-Qahtani, A.A.; Alenzi, A.A.S. Preliminary findings of a study on the practice of self-medication of antibiotics among the practicing nurses of a tertiary care hospital. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, M.; Mustafa, S.; Ali, S. Self-medication among undergraduate medical students in Kuwait with reference to the role of the pharmacist. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kanchan, T.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Rekha, T.; Mithra, P.; Kulkarni, V.; Papanna, M.K.; Holla, R.; Uppal, S. Perceptions and practices of self-medication among medical students in coastal South India. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukovic, J.A.; Miletic, V.; Pekmezovic, T.; Trajkovic, G.; Ratkovic, N.; Aleksic, D.; Grgurevic, A. Self-Medication Practices and Risk Factors for Self-Medication among Medical Students in Belgrade, Serbia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, D. Self-medication patterns among nursing students in North India. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2013, 11, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aquino, D.S.; de Barros, J.A.C.; da Silva, M.D.P. A automedicação e os acadêmicos da área de saúde. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2010, 15, 2533–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Incidência da Automedicação em Graduandos de Enfermagem, Repositório Digit. UNIP. Available online: https://repositorio.unip.br/journal-of-the-health-sciences-institute-revista-do-instituto-de-ciencias-da-saude/incidencia-da-automedicacao-em-graduandos-de-enfermagem/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Azodo, C.; Ehigiator, O.; Ehigiator, L.; Ehizele, A.; Ezeja, E.; Madukwe, I. Self-medication practices among dental, midwifery and nursing students. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2013, 2, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Sekhar, H.S.; Alex, T.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Chopra, R.S. Self medication practice among medical, pharmacy and nursing students. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 443–447. [Google Scholar]

- Gama, A.S.M.; Secoli, S.R. Self-medication among nursing students in the state of Amazonas—Brazil. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2017, 38, e65111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharati, J.P.; Ulak, S.; Shrestha, M.V.; Dixit, S.M.; Acharya, A.; Bhattarai, A. Self-medication in Primary Dysmenorrhea among Medical and Nursing Undergraduate Students of a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2021, 59, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.E.; Pereira, G.A.F.; Ribeiro, L.G.M.; Nunes, R.; Ilias, D.; Navarro, L.G.M. Study of self-medication for musculoskeletal pain among nursing and medicine students at Pontifícia Universidade Católica—São Paulo. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2014, 54, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.A.F.; da Silva, C.D.; Ferraz, G.C.; Sousa, F.A.E.F.; Pereira, L.V. The prevalence and characterization of self-medication for obtaining pain relief among undergraduate nursing students. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2011, 19, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqihi, A.H.M.A.; Sayed, S.F. Self-medication practice with analgesics (NSAIDs and acetaminophen), and antibiotics among nursing undergraduates in University College Farasan Campus, Jazan University, KSA. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2021, 79, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroush, A.; Abdi, A.; Andayeshgar, B.; Vahdat, A.; Khatony, A. Exploring the perceived factors that affect self-medication among nursing students: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nurses | Self-medication | For any disease (n = 106) | For dermatological diseases (n = 90) | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 38.91 | ±12.65 | 39.62 | ±12.36 | ||

| Years of practice | 14.03 | ±12.09 | 15.41 | ±12.20 | ||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 11 | 10.38 | 7 | 7.78 | |

| Female | 95 | 89.62 | 83 | 92.22 | ||

| Practice setting | MD | 73 | 68.87 | 60 | 66.67 | |

| S | 4 | 3.77 | 4 | 4.44 | ||

| MD-S | 29 | 27.36 | 26 | 28.89 | ||

| Nursing students | Self-medication | For any disease (n = 256) | For dermatological diseases (n = 157) | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 20.75 | ±4.82 | 21.45 | ±5.91 | ||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 32 | 12.50 | 17 | 10.83 | |

| Female | 224 | 87.50 | 140 | 89.17 | ||

| Academic year | First | 149 | 58.20 | 86 | 54.78 | |

| Second | 62 | 24.22 | 42 | 26.75 | ||

| Third | 36 | 14.06 | 22 | 14.01 | ||

| Fourth | 9 | 3.52 | 7 | 4.46 | ||

| Nurses (n = 87) | Nursing students (n = 152) | ||||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Topical treatment | Antifungal | 31 | 35.63 | 18 | 11.84 |

| Antibiotic | 26 | 29.89 | 32 | 21.05 | |

| Corticosteroid | 57 | 65.52 | 54 | 35.53 | |

| Retinoid | 5 | 5.75 | 2 | 1.32 | |

| Antihistamine | 20 | 22.99 | 17 | 11.18 | |

| Corticosteroid + antifungal | 12 | 13.79 | 1 | 0.66 | |

| Corticosteroid + antibiotic | 10 | 11.49 | 7 | 4.61 | |

| Other | 3 | 3.45 | 1 | 0.66 | |

| Could not remember | 3 | 3.45 | 3 | 1.97 | |

| Nurses (n = 33) | Nursing students (n = 57) | ||||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Oral treatment | Antifungal | 10 | 10.30 | 4 | 7.02 |

| Antibiotic | 6 | 18.18 | 7 | 12.28 | |

| Corticosteroid | 6 | 18.18 | 2 | 3.51 | |

| Antihistamine | 16 | 48.48 | 11 | 19.30 | |

| Other | 3 | 9.09 | 3 | 5.26 | |

| Not remembered | 1 | 3.03 | 36 | 63.16 | |

| Nurses (n = 90) | Nursing students (n = 157) | ||||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Skin diseases | Acne | 11 | 12.22 | 63 | 40.13 |

| Psoriasis | 3 | 3.33 | 7 | 4.46 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 17 | 18.89 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| Allergic or irritative contact dermatitis | 32 | 35.56 | 33 | 21.02 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 8 | 8.89 | 8 | 5.1 | |

| Other eczemas | 8 | 8.89 | 27 | 17.20 | |

| Melanocytic nevi | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| Urticaria | 5 | 5.56 | 13 | 8.28 | |

| Fungal infections | 26 | 28.89 | 9 | 5.73 | |

| Bacterial infections | 10 | 11.11 | 7 | 4.46 | |

| Parasitic infections | 4 | 4.44 | 2 | 1.27 | |

| Warts | 3 | 3.33 | 2 | 1.27 | |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Insect bites | 21 | 23.33 | 27 | 17.20 | |

| Skin burns | 20 | 22.22 | 25 | 15.92 | |

| Other | 4 | 4.44 | 9 | 5.73 | |

| Not remembered | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| Unknown diagnosis | 2 | 2.22 | 11 | 7.01 | |

| Nurses (n = 35) | Nursing Students (n = 17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

| Own knowledge about the disease and its treatment | 32 | 91.43 | 10 | 58.82 |

| Medicine books/journals | 6 | 17.14 | 1 | 5.88 |

| Internet | 3 | 8.57 | 6 | 35.29 |

| Advertisement on television | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 5.88 |

| Other | 2 | 5.71 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Self-Medication | For any Disease (n = 120) | For Dermatological Diseases (n = 106) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p value | Mean | p value | |||||

| Average years of professional practice | Yes | 14.02 | 0.304 * | 15.41 | <0.001 * | |||

| No | 10.50 | 6.25 | ||||||

| Cohen’s d = 0.895 | ||||||||

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | p value | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | p value | |||

| Number of nurses (%) by years of professional practice | <5 years | 39 | 36.80 | p = 0.1681 # | 28 | 31.1 | p = 0.014 # | |

| 5–15 years | 17 | 16.00 | 15 | 16.70 | ||||

| >15 years | 50 | 47.20 | 47 | 52.20 | ||||

| >15 years vs. <5 years: OR 6.15 (1.58–23.97) >15 years vs. 5–15 years: OR 2.09 (0.32–13.71) | ||||||||

| Self-Medication | For Any Disease (n = 303) | For Dermatological Diseases (n = 256) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p value | Mean | p value | ||

| Average age (years) | Yes | 20.75 | 0.014 * | 21.45 | <0.001 * |

| No | 19.74 | 19.63 | |||

| Cohen’s d = 0.277 | Cohen’s d = 0.419 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Batalla, A.; Martínez-Santos, A.-E.; Braña Balige, S.; Varela Fontán, S.; Vilanova-Trillo, L.; Diéguez, P.; Flórez, Á. Dermatology Self-Medication in Nursing Students and Professionals: A Multicentre Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020258

Batalla A, Martínez-Santos A-E, Braña Balige S, Varela Fontán S, Vilanova-Trillo L, Diéguez P, Flórez Á. Dermatology Self-Medication in Nursing Students and Professionals: A Multicentre Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020258

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatalla, Ana, Alba-Elena Martínez-Santos, Sara Braña Balige, Sara Varela Fontán, Lucía Vilanova-Trillo, Paz Diéguez, and Ángeles Flórez. 2024. "Dermatology Self-Medication in Nursing Students and Professionals: A Multicentre Study" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020258

APA StyleBatalla, A., Martínez-Santos, A.-E., Braña Balige, S., Varela Fontán, S., Vilanova-Trillo, L., Diéguez, P., & Flórez, Á. (2024). Dermatology Self-Medication in Nursing Students and Professionals: A Multicentre Study. Healthcare, 12(2), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020258