Domains and Categories of Needs in Long-Term Follow-Up of Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

- What are the needs in long-term follow-up of cancer survivors?

- Are there socio-demographic differences in the needs (e.g., age, gender, marital status, income, location, etc.)?

- Are the needs greater in the transition phase (directly after acute treatments)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Study design: Systematic reviews;

- Published in peer-review journals;

- Languages: English, French and German;

- Focusing on cancer survivors:

- ○

- All kinds of cancer;

- ○

- Male or female;

- ○

- Curative intent;

- Studies from high-income countries.

- Other study designs, conference proceedings (in the absence of a full-text paper);

- Publications older than 2011;

- Focusing on cancer survivors <18 years old (at diagnosis);

- Time since diagnosis <2 years;

- Studies focusing on specific supportive care needs (e.g., physiotherapy);

- Studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC);

- Focusing on the indigenous population of high-income countries (HIC).

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

- (a)

- Selection based on titles: the first author (N.Sp.) selected based on the titles of the articles. A second author (D.K.) reviewed the titles of excluded articles, and any differences of opinion were discussed between them;

- (b)

- Selection based on abstracts by two independent reviewers (N.Sp., D.K.). The results were compared and any differences in the selection of the reviewers were discussed on a case-by-case basis. Reasons for excluding studies were reported;

- (c)

- Selection based on the full texts by the first author (N.Sp.). If there were any doubts, the lead author discussed them with the other authors of the review. Reasons for excluding studies were reported. The reference lists of the selected studies were searched for further studies.

2.4. Data Charting Process

2.5. Data Items

- Source: title, author(s), year, journal, DOI/ISBN;

- Characteristics of the study: number of included articles, objectives, database consulted, inclusion/exclusion criteria, bias, results of the quality appraisal;

- Population: age, gender, cancer type, number of participants;

- Concept: domains of needs;

- Context: country, period (of the studies), setting;

- Results: needs, unmet needs, conclusion, recommendation for screening tool, influence of the comorbidities, influence of socio-demographical factors, information about the transitional phase.

2.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.7. Synthesis of the Results

3. Results

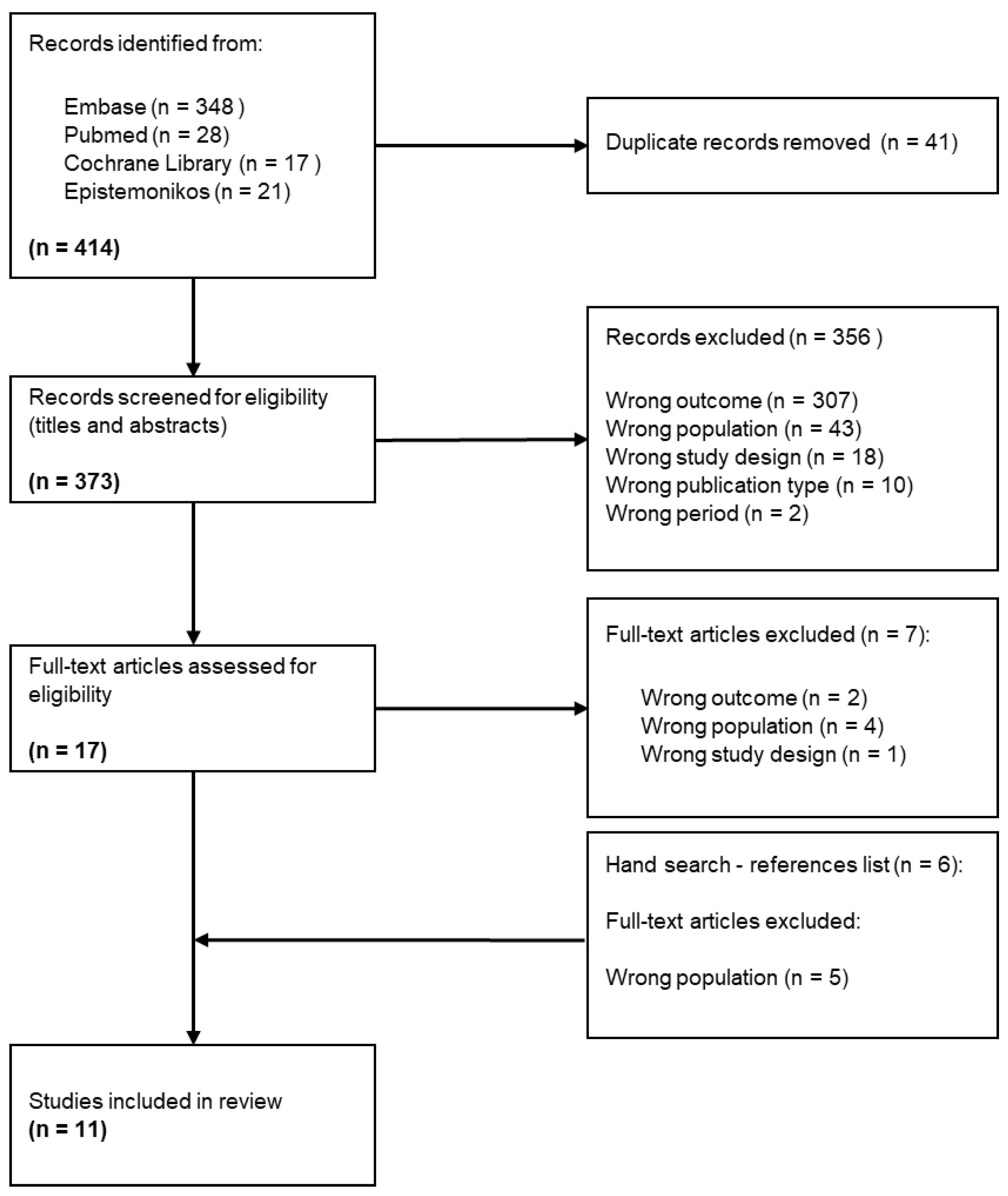

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Critical Appraisal within Sources of Evidence

3.4. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

3.5. Synthesis of Results

3.5.1. Health-Related Information

3.5.2. Health System

3.5.3. Mental

3.5.4. Practical

3.5.5. Relationship

3.5.6. Physical

3.5.7. Socio-Demographic Factors

3.5.8. Transition Phase

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Review Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Concept 1 | Concept 2 | Concept 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Needs | Follow-Up | Cancer Survivors |

| MESH (pubmed) | And Needs assessment [Mesh] Health Services Needs and Demand [Mesh] Health Services Needs Needs | And Aftercare[Mesh: NoExp] After Care After-Treatment Continuity of Patient Care”[Mesh:NoExp]) “Transitional Care”[Mesh] | And “Cancer Survivors”[Mesh] (Exclude children, adolescents and adults diagnosed with cancer before the age of 18) |

| EMTREE (Embase) | ‘needs’/exp ‘human needs’/exp ‘unmet needs’/exp ‘health care need’/de ‘supportive care need’/exp ‘unmet medical need’/exp ‘long term care’/exp | ‘aftercare’/exp ‘patient care’/de ‘case management’/exp ‘patient care planning’/exp ‘patient decision making’/exp ‘patient monitoring’/de ‘monitoring’/de ‘questionnaire’/de ‘navigation’/exp ‘care coordination’/exp | ‘cancer survival’/de ‘cancer survivor’/exp |

| APA THESAURUS | Psychological needs Health service needs Needs assessment | Aftercare Posttreatment followup Case management Long term care Interpersonal interaction | Neoplasm |

| Free vocabulary Synonyms Related terms | Needs Assessments Unmet needs Supportive care needs Long-term care needs Care process needs Assessment of Healthcare Needs and Demand Health Services Needs Services needs Information needs | Follow-up Followup Monitoring Survey and questionnaires Surveillance Case management Navigation After treatment Aftertreatment Communication Coordination Aftercare After care Continuity of patient care Patient report | Cancer survivors Cancer survivorship |

Appendix B. Search Strategy—Pubmed

References

- WHO. Cancer Tomorrow. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- WHO. Number of Deaths Caused by Selected Chronic Diseases Worldwide as of 2019 (in 1000) [Graph]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/265089/deaths-caused-by-chronic-diseases-worldwide/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- WHO. World Factsheet. In International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/39-all-cancers-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Mullan, F. Seasons of Survival: Reflections of a Physician with Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 313, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; Merry, B.; Miller, J. Seasons of Survivorship Revisited. Cancer J. 2008, 14, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefford, M.; Karahalios, E.; Pollard, A.; Baravelli, C.; Carey, M.; Franklin, J.; Aranda, S.; Schofield, P. Survivorship Issues Following Treatment Completion-Results from Focus Groups with Australian Cancer Survivors and Health Professionals. J. Cancer Surviv. 2008, 2, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.K. Transition to Cancer Survivorship: A Concept Analysis. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 41, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbez, B.; Rollin, Z. Sociologie du Cancer; La Découverte; Collection Repères: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-2-7071-8286-9. [Google Scholar]

- Firkins, J.; Hansen, L.; Driessnack, M.; Dieckmann, N. Quality of Life in “Chronic” Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperisen, N.; Stoll, S.; Bana, M. Survivorship. In Onkologische Krankenpflege; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Delivering Cancer Survivorship Care. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 187–321. ISBN 978-0-309-09595-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Miami, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, V.; Laan, E.T.M.; den Oudsten, B.L. Sexual Health-Related Care Needs among Young Adult Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 16, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, S.Y.; Delfabbro, P. Are You a Cancer Survivor? A Review on Cancer Identity. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I. Take Care When You Use the Word Survivor. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2019, 29, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, A.; Feder, G.; MacPherson, H.; Little, P.; Mercer, S.W.; Sharp, D. Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews of Complementary Medicine for Musculoskeletal and Mental Health Conditions. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotronoulas, G.; Papadopoulou, C.; Burns-Cunningham, K.; Simpson, M.; Maguire, R. A Systematic Review of the Supportive Care Needs of People Living with and beyond Cancer of the Colon and/or Rectum. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 29, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, R.; Kotronoulas, G.; Simpson, M.; Paterson, C. A Systematic Review of the Supportive Care Needs of Women Living with and beyond Cervical Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 136, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, Y.G.; Alhashemi, A.; Fazelzad, R.; Goldberg, A.S.; Goldstein, D.P.; Sawka, A.M. A Systematic Review of Unmet Information and Psychosocial Support Needs of Adults Diagnosed with Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miroševič, Š.; Prins, J.B.; Selič, P.; Zaletel Kragelj, L.; Klemenc Ketiš, Z. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Unmet Needs in Post-treatment Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, L.; Wittrup, I.; Væggemose, U.; Petersen, L.K.; Blaakaer, J. Life After Gynecologic Cancer—A Review of Patients Quality of Life, Needs, and Preferences in Regard to Follow-Up. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, R.A.; Heins, M.J.; Korevaar, J.C. Health Care Needs of Cancer Survivors in General Practice: A Systematic Review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.Y.S.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.C.; Young, J.M.; Kao, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Butow, P. Colorectal Cancer Survivorship: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisy, K.; Langdon, L.; Piper, A.; Jefford, M. Identifying the Most Prevalent Unmet Needs of Cancer Survivors in Australia: A Systematic Review. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 15, e68–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, E.; Vlerick, I.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Pattyn, P.; Van de Putte, D.; van Ramshorst, G.H.; Geboes, K.; Van Hecke, A. Experiences and Needs of Patients with Rectal Cancer Confronted with Bowel Problems after Stoma Reversal: A Systematic Review and Thematic-Synthesis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 54, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruk, S.R.; Butow, P.; Mesters, I.; Boyle, T.; Olver, I.; White, K.; Sabesan, S.; Zielinski, R.; Chan, B.A.; Spronk, K.; et al. Psychosocial Well-Being and Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Patients and Survivors Living in Rural or Regional Areas: A Systematic Review from 2010 to 2021. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1021–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, M.I. Supportive Care Framework. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2008, 18, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.; Griffin, G.; Farrell, V.; Hauck, Y.L. Gaining Insight into the Supportive Care Needs of Women Experiencing Gynaecological Cancer: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 1684–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, C.; Peytremann Bridevaux, I.; Eicher, M. The Swiss Cancer Patient Experiences-2 (SCAPE-2) Study: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Survey of Patient Experiences with Cancer Care in the French- and German-Speaking Regions of Switzerland; Unisanté: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Ford, P.J.; Farah, C.S. “I Have Quality of Life… but…”: Exploring Support Needs Important to Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMillan. Cancer Support Cancer Self-Help and Support Groups. Available online: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/get-help/emotional-help/local-support-groups (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Chambers, S.K.; Hyde, M.K.; Laurie, K.; Legg, M.; Frydenberg, M.; Davis, I.D.; Lowe, A.; Dunn, J. Experiences of Australian Men Diagnosed with Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.E.; Doroudi, M.; Yabroff, K.R. Financial Hardship. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 111–125. ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, H.R.; Durbin, S.; Huang, C.X.; Johnson, S.F.; Nayak, R.K.; Zahner, G.J.; Peppercorn, J. Financial Toxicity in Cancer Care: Origins, Impact, and Solutions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2043–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleaume, C.; Bousquet, P.-J.; Joutard, X.; Paraponaris, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Vernay, P. Situation Professionnelle Cinq Ans Après Un Diagnostic de Cancer. In La Vie cinq Ans après Diagnostic de Cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa): Paris, France, 2018; pp. 174–201. [Google Scholar]

- Alleaume, C.; Bousquet, P.-J.; Joutard, X.; Paraponaris, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V. Trajectoire Professionnelle Après Un Diagnostic de Cancer. In La Vie cinq Ans après un Diagnostic de Cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa): Paris, France, 2018; pp. 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Von Ah, D.; Duijts, S.; van Muijen, P.; de Boer, A.; Munir, F. Work. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 227–242. ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ancellin, R.; Ben Diane, M.-K.; Bouhnik, A.-D.; Mancini, J.; Menard, E.; Monet, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Sarradon-Eck, A. Alimentation et Activité Physique. In La Vie cinq Ans après un Diagnostic de Cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa): Paris, France, 2018; pp. 278–297. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, A.; Monet, A.; Peretti-Watel, P. Consommation de Tabac et d’alcool. In La Vie cinq Ans après un Diagnostic de Cancer; Institut National du Cancer (INCa): Paris, France, 2018; pp. 298–311. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Robinson, L.A.; Jensen, R.E.; Smith, T.G.; Yabroff, K.R. Factors Associated With Health-Related Quality of Life Among Cancer Survivors in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021, 5, pkaa123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, E.E.; Jones, J.; Syrjala, K.L. Comprehensive Healthcare. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 363–380. ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, J.S.; Riley, K.E.; Dhingra, L.K. Smoking. In Handbook of Cancer Survivorship; Feuerstein, M., Nekhlyudov, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 329–345. ISBN 978-3-319-77430-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Mollica, M.A.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Mayer, D.K.; Shulman, L.N.; Geiger, A.M. Developing a Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework: Implications for Clinical Care, Research and Policy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, B.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, C.; Han, L. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, M.S.Y.; van Noorden, C.J.F.; Steindorf, K.; Arndt, V. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Causes and Current Treatment Options. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperisen, N.; Cardinaux-Fuchs, R.; Schneider-Mörsch, B.; Stoll, S.; Haslbeck, J. Cancer Navigation and Survivorship. Onkologiepflege; Onkologiepflege Schweiz, Kleinandelfingen, Switzerland, 2021, pp. 12–14. Available online: https://www.onkologiepflege.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/zeitschrift/2021_1_Onkologiepflege_Soinsenoncologie.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Riley, S.; Riley, C. The Role of Patient Navigation in Improving the Value of Oncology Care. J. Clin. Pathw. 2016, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bellas, O.; Kemp, E.; Edney, L.; Oster, C.; Roseleur, J. The Impacts of Unmet Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Survivors in Australia: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization. World Health Organization Supportive, Survivorship and Palliative Care. In WHO REPORT ON CANCER: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 94–97. ISBN 978-92-4-000129-9. [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Survivorship Care for Cancer-Related Late and Long-Term Effects 2020; NCCN: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. TARGET ARTICLE: “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence”. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Ganz, P.A. Life after Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer in Adulthood: Contributions from Psychosocial Oncology Research. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Characteristics of the Studies | Context | Population | Limitations | Critical Appraisal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim of the Studies | Number of Included Articles | Period of Analysis (of the Studies) | Countries | Number of Participants (Range) | Gender | Cancer Type | |||

| Dahl et al. (2013) [23] | To investigate knowledge on the quality of life after cancer, which factors could be predictors, and knowledge on gynecological cancer patients’ needs and preferences regarding follow-up. | 57 | 1995–2012 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Gynecological |

| Not sufficient quality |

| Hoekstra et al. (2014) [24] | To report how adult cancer survivors describe their care needs in the general practice environment. | 15 | 1990–2012 |

| 970 (6–431) | Men Women |

|

| Good quality |

| Hyun et al. (2016) [21] | To examine the unmet information needs and the unmet psychosocial support needs of adult thyroid cancer survivors. | 7 | 2008–2016 |

| 6215 | Majority of women | Thyroid |

| Sufficient quality |

| Kotronoulas et al. (2017) [19] | To synthesize evidence in relation to the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. | 45 | 1996–2016 |

| 10,057 (5–3011) | Men (64.5%) Women (35.5%) | Colon and/or rectum |

| Good quality |

| Lehmann et al. (2021) [14] | To identify the prevalence of sexual health-related care needs and the types of needs that should be addressed by providers. | 35 | 2004–2019 |

| 5938 (8–879) | Majority of women |

|

| Sufficient quality |

| Lim et al. (2021) [25] | To synthesize the current body of qualitative research on colorectal cancer survivorship as early as the immediate post-operative period, and to compare the experiences of early stage and advanced colorectal cancer survivors. | 81 | 2006–2019 |

| Not reported | Not reported | Colon and/or rectum |

| Sufficient quality |

| Lisy et al. (2019) [26] | To identify the most prevalent unmet needs of cancer survivors in Australia and to identify demographic, disease, or treatment-related predictors of unmet needs. | 17 | 2007–2018 | Australia | Not reported | Not reported |

|

| Sufficient quality |

| Maguire et al. (2015) [20] | To synthesize evidence with regard to the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer. | 14 | 1990–2013 |

| 1414 (10–968) | Women | Cervical |

| Good quality |

| Miroševič et al. (2019) [22] | To determine the prevalence and identify the factors that contribute to higher levels of the unmet needs. To identify the most commonly unmet needs and those factors that contribute to higher levels of unmet needs in each domain separately. | 26 | 2007–2015 |

| 10,533 (63–1668) | Men Women |

|

| Sufficient quality |

| Pape et al. (2021) [27] | To describe the experiences and needs of patients with rectal cancer confronted with bowel problems after stoma reversal. | 10 | 2006–2021 |

| 156 (5–36) | Men (approx. 58%) Women (approx. 42%) | Rectal with Stoma reversal |

| Good quality |

| Van der Kruk et al. (2021) [28] | To review levels of psychosocial morbidity and the experiences and needs of people with cancer and their informal caregivers, living in rural or regional areas. | 65 | 2010–2021 |

| Not reported | Not reported |

|

| Sufficient quality |

| Domains of Needs | Definition | Categories of Needs | Examples of Challenges | Number of Studies Reporting These Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related information | Need to receive and process adequate information on all types of subjects to meet certain objectives. | Access | Lack of information (all kinds of information), quality and delivery of information. | 10 |

| Education | Difficulties to process information, comprehension, and quality assessment. | |||

| Health system | Need to access a personalized, comprehensive, and integrated care and support pathway to reduce or treat the consequences of the disease and/or treatments. | Healthcare professionals | Lack of knowledge of the unique needs of rural survivors by medical staff located in metropolitan treatment centers, on-going patient–clinician contact, post-operative follow-up (hospital doctor) or post-treatment follow-up (specialist nurse), helping with common (late) treatment effect, initialization of discussions about sexual health by providers, empathic and sensitive discussion on sexual health, overcome taboos, enough time to discuss sensitive matters. | 10 |

| Health and supportive care | Coordination of health care services (primary and secondary), access to counselling/support groups, access to complementary/alternative medicine, gap in supportive care, medical help/treatment for non-cancer related problems, general preventative healthcare, access and continuity of care, comprehensive care, regular monitoring of needs, navigation in health system. | |||

| Mental | Supportive care needs to reduce emotional, existential, interpersonal and/or psychic health conditions, due to illness and/or treatment, that disrupt a person’s behavior or reasoning. | Emotional | Deal with altered body image, appearance (attractiveness, self-image, desirability, femininity), emotional health. | 9 |

| Existential | Fear of cancer recurrence, uncertainty, adversity, lifestyle changes, worries about the future. | |||

| Interpersonal/intimacy | Changes in sexuality, coping with sexual dysfunction, lack of sexual desire, anxiety about sexual intercourse, feeling to be forced to fulfill the partner’s sexual desires (cultural pressure and expectation). | |||

| Psychic | Stress, feeling of abandonment after treatment, anxiety, distress, depression. | |||

| Practical | Need for support to limit the impact of the disease and/or treatment on daily life. | Daily activities | Not being able to do usual things, transportation, identification, and integration of health behaviors. | 7 |

| Financial impact | Financial well-being, worry about earning money, fighting financial toxicity. | |||

| Work | Return to work, adapting work to new capacities (position, schedule, workload, etc.), change of professional activity, reactions of colleagues/leaders. | |||

| Relationship | Need for support to reduce or deal with the consequences of the illness and/or treatments that disrupt interactions with the family and the social environment. | Family | Support of family for its own worries, family’s future, worry about partners and family. | 6 |

| Social | Embarrassment in social situations, relationships with others, lack of practical and emotional support from peers and the environment, difficulties and tensions in relationships, isolation, social role change, social desirability. | |||

| Physical | Supportive care needs to alleviate or treat the physical and cognitive consequences of the disease and/or treatments. | Body | Fatigue/lack of energy, pain, physical problems, dysfunction, sleep loss, urinary incontinence, bowel dysfunction, difficulty breathing, infertility, hormone changes, loss of strength, nausea/vomiting, neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, skin irritation, weight changes, infected or bleeding wound, mouth- or eye-related, physical examination, managing side-effects (physical symptoms). | 6 |

| Cognitive | Memory loss, difficulty concentrating or cognitive dysfunction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sperisen, N.; Kohler, D.; Steck, N.; Dietrich, P.-Y.; Rapiti, E. Domains and Categories of Needs in Long-Term Follow-Up of Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111058

Sperisen N, Kohler D, Steck N, Dietrich P-Y, Rapiti E. Domains and Categories of Needs in Long-Term Follow-Up of Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare. 2024; 12(11):1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111058

Chicago/Turabian StyleSperisen, Nicolas, Dimitri Kohler, Nicole Steck, Pierre-Yves Dietrich, and Elisabetta Rapiti. 2024. "Domains and Categories of Needs in Long-Term Follow-Up of Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews" Healthcare 12, no. 11: 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111058

APA StyleSperisen, N., Kohler, D., Steck, N., Dietrich, P.-Y., & Rapiti, E. (2024). Domains and Categories of Needs in Long-Term Follow-Up of Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare, 12(11), 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111058