Community Dynamics and Engagement Strategies in Establishing Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Systems: A Multi-Site Report from India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- The Gokulpuri DDESS is an urban low-income neighbourhood in the North-East district of Delhi comprising an urban resettlement colony, urban slum, and a village. Of the total population, 91.6% are literate, 94.94% belong to the Hindu religion, and 52.28% belong to the scheduled caste. The settlement has very few (i.e., 4) health care facilities, while the nearest referral health facility is around 6–7 km away.

- The Dakshinpuri DDESS is an urban low-income neighbourhood located in the Southern district of Delhi. A total of 99.55% of the population is urban and 78.91% follow the Hindu religion, followed by the Muslim and Sikh religions. The settlement has 3 healthcare facilities for local residents.

- The Mawphlang DDESS spreads across the 364.48 Sq Km area in the Mawphlang and Sohiong administrative blocks of the East Khasi Hills district of Meghalaya state. The site is predominantly occupied by the Khasi tribal community (99.5%). In total, 80.7% of the population are Christians and the site has very high literacy rates (82.8%). There are 2 community health centres, 1 primary health centre and 9 sub-centres.

- The Tigiria DDESS is a predominantly rural area (89.2%). A total of 95.17% of people belong to the Hindu religion, followed by other minority communities. The majority belong to the upper caste (83.4%), followed by the schedule caste (13.2%) and the schedule tribe (3.4%). Cultivation is the main occupation. While the site has 2 community health centres, 4 primary health centres and 13 sub-centres, the referral health centre is around 15–20 km away.

- The Simhachalam DDESS is located in the western part of Visakhapatnam and is predominantly peri-urban. A total of 95.9% of the population belong to the Hindu religion. The scheduled caste (7.6%) and scheduled tribe (14.3%) constitute one fourth of the population. Occupations are mostly service or running small businesses. The site has the fair availability of 92 hospitals in the urban setting and 13 hospitals in the rural setting, respectively. The Marakanam, Chitamur, and Muthialpet DDESS is predominantly rural, with the average literacy rate being 65.2%. The major occupations are agriculture and fishing. The site has an availability of 48 hospitals in the rural setting, compared to only 2 hospitals in the urban facilities for the residents.

| SAS | MAMC | AMC | RMRC | PIMS | INCLEN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics * | N = 55,445 | N = 54,614 | N = 55,529 | N = 76,379 | N = 56,025 | N = 85,123 |

| Gender-wise distribution | ||||||

| Male | 28,513 (51.43%) | 28,951 (53.01%) | 27,482 (49.5%) | 40,026 (52.40%) | 27,571 (49.21%) | 41,659 (48.9%) |

| Female | 26,909 (48.53%) | 25,661 (46.99%) | 28,045 (50.5%) | 36,349 (47.59%) | 28,452 (50.78%) | 43,464 (51.1%) |

| Others (3rd Gender) | 23 (0.04%) | 2 (0.01%) | 2(0%) | 4 (0.01%) | 2 (0.00%) | 0 |

| Age-wise distribution | ||||||

| Up to 5 yrs | 4205 (0.69%) | 4650 (8.51%) | 3601 (6.4%) | 5772 (7.56%) | 4144 (7.40%) | 13,999 (16.5%) |

| 6–14 yrs | 7937 (4.85%) | 8213 (15.04%) | 7026 (12.6%) | 9802 (12.83%) | 7361 (13.14%) | 20,212 (23.7%) |

| 15–45 yrs | 32,787 (58.1%) | 31,050 (56.85%) | 30,198 (54.3%) | 38,772 (50.76%) | 29,337 (52.36%) | 40,931 (48.1%) |

| 46–59 yrs | 6240 (19.2%) | 6472 (11.85%) | 9450 (17%) | 11,891 (15.57%) | 8286 (14.79%) | 6041 (7.1%) |

| More than equal to 60 yrs | 4276 (17.2%) | 4229 (7.74%) | 5254 (9.4%) | 10,142 (13.28%) | 6897 (12.31%) | 3940 (4.6%) |

| Religion-wise distribution * | ||||||

| Hindu | 49,013 (88.4%) | 51,857 (94.95%) | 52,378 (94.3%) | 72,493 (94.91%) | 51,223 (91.43%) | 49 (0.06%) |

| Muslim | 4700 (8.5%) | 2417 (4.43%) | 977 (1.8%) | 2629 (3.44%) | 2962 (5.29%) | 14 (0.02%) |

| Christian | 925 (1.7%) | 84 (0.15%) | 1894 (3.4%) | 25 (0.03%) | 1657 (2.96%) | 68,693 (80.7%) |

| Jain | 42 (0.1%) | 95 (0.17%) | 13 (0%) | 21 (0.03%) | 4 (0.01%) | 0 |

| Buddhist | 51 (0.1%) | 19 (0.3%) | 4 (0%) | 1205 (1.58%) | 0 | 0 |

| Sikh | 609 (1.1%) | 119 (0.22%) | 6 (0%) | 6 (0.01%) | 0 | 34 (0.04%) |

| Others | 180 (0.32%) | Khasi 15,301 (17.9%) | ||||

| Caste-wise distribution | ||||||

| General | 16,296 (29.4%) | 19,655 (35.99%) | 9267 (17%) | 16,855 (22.07%) | 1155 (2.06%) | 36 (0.04%) |

| Scheduled Caste (SC) | 31,140 (56.2%) | 19,748 (36.16%) | 7265 (13%) | 8224 (10.77%) | 7104 (12.68%) | 129 (0.1%) |

| Scheduled Tribe (ST) | 348 (0.6%) | 1192 (2.18%) | 1165 (2%) | 5382 (7.05%) | 2103 (3.75%) | 84,922 (99.7%) |

| Other Backward Caste (OBC) | 5321 (9.6%) | 13,230 (24.22%) | 37,693 (68%) | 45,878 (60.07%) | 42,757 (76.32%) | 27 (0.03%) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 26,185 (47.2%) | 26,474 (48.47%) | 34,146 (61.4%) | 46,610 (61.02%) | 33,508 (59.81%) | 26,630 (31.2%) |

| Unmarried | 25,849 (46.6%) | 25,444 (45.59%) | 21,383 (38.5%) | 29,787 (39%) | 22,517 (40.19%) | 52,869 (62.2%) |

| Literacy status | ||||||

| Literate | 45,895 (82.8%) | 47,735 (87.40%) | 43,361 (78.08%) | 65,755 (86.09%) | 51,342 (91.64%) | 70,301 (82.8%) |

| Illiterate | 4608 (8.31%) | 4558 (8.35%) | 12,168 (21.92%) | 10,624 (13.38%) | 4683 (8.36%) | 6423 (7.6%) |

3. Results

- (A)

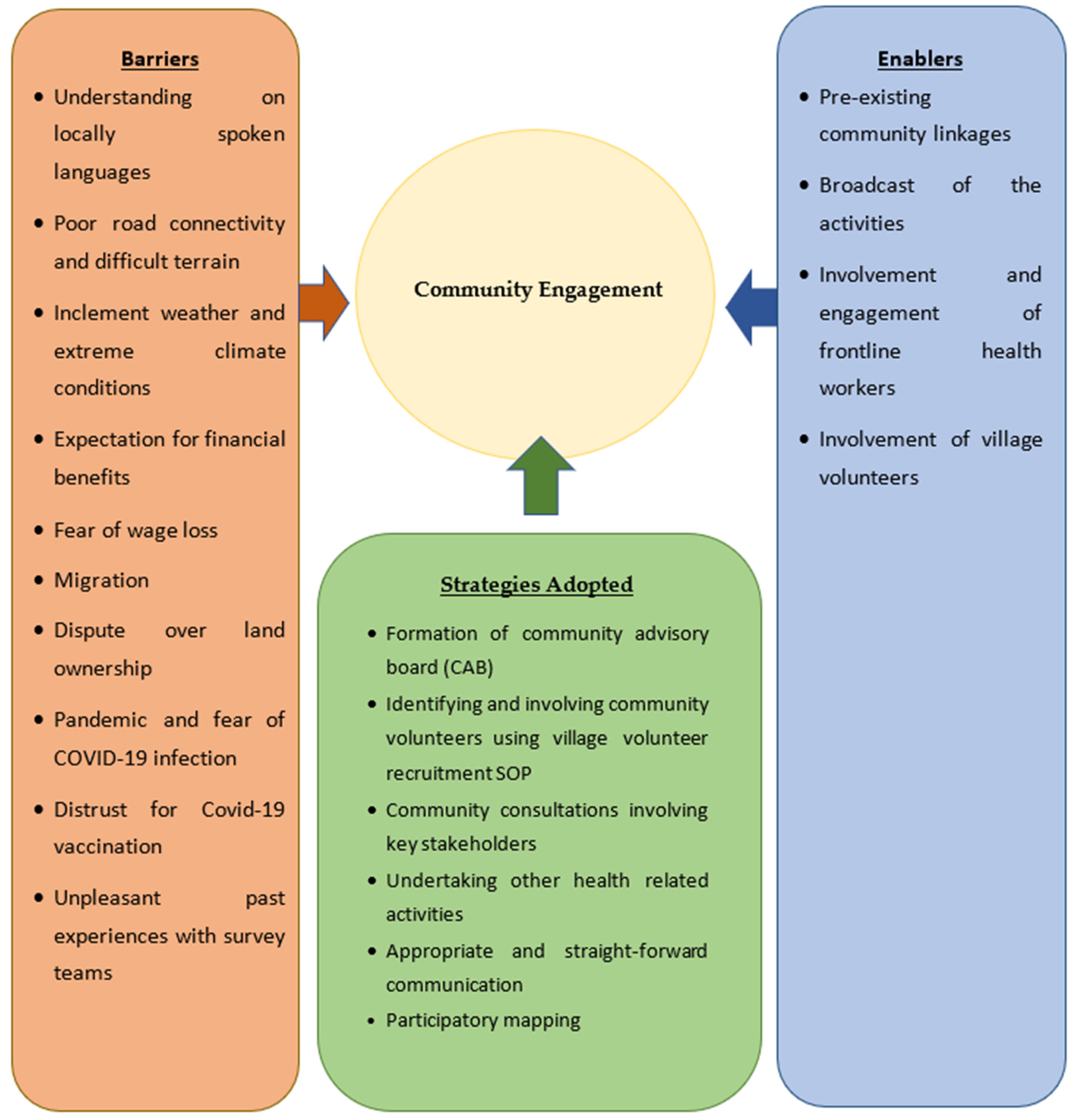

- Barriers encountered during community engagement (CE). The significance of CE exists both during the establishment of the DDESS and ensuing quality data collection from the sites. The research teams encountered many barriers and challenges in the process of ensuring adequate CE. While some common challenges were observed in multiple sites, some were site-specific:

- Limited or lack of understanding of locally spoken languages: India is the world’s most linguistically diverse country. Absence of familiarity with the locally spoken language and dialect posed challenges for investigators and project staff, especially in remote and tribal regions with predominantly indigenous populations. For instance, Khasi, an Austroasiastic language, is predominantly spoken in the tribal areas of Mawphlang and Sohiong blocks of the North-Eastern state of Meghalaya, having just over 1 million speakers. This caused difficulty for site investigators unfamiliar with the local language to communicate with members of the local community that precluded effective CE and the data collection processes.

- Poor road connectivity and difficult terrain: Some DDESS sites were located in areas (rural and tribal) that were not connected with all-weather motorable roads and caused difficult access. The survey team had to travel considerable distances by foot to reach these remote villages. The interior areas located in forest and hilly terrain were difficult to reach, and more so during the rainy season.

- Inclement weather and extreme climatic conditions: While DDESS sites in Meghalaya were the wettest, the site of Odisha is near the riverine regions. Such sites are prone to flood and difficult to carry out field activities in during the rainy seasons. The temperature extremities (summer in southern DDESS sites and winter in the northern part) and heavy rainfall were also detrimental to conducting routine project activities.

- Expectation for financial benefits: Some community members had expectations of financial gain or compensation for participating in or facilitating the project and research activities in their sites. In the absence of provision for any direct financial benefit, such members were disinclined to participate or consent.

- Fear of wage loss: Some family members, especially the adults who were mainly involved in earning livelihoods for their family, could not afford to spend time with the team during their working hours.

- Migration: Some people migrate in search of jobs, even with their family. This causes a loss in follow-up of the registered population and a challenge to DDESS sustainability.

- Dispute over land ownership: Households with prevailing legal disputes about their land ownership were initially found to be resentful and reluctant to share any of their personal information as part of the study. In hilly areas, even the village councils are involved in disputes over the village boundaries, and some of them do not agree with the inter-village boundaries given in the government records.

- Pandemic and fear of COVID-19 infection: The COVID-19 pandemic created a lot of panic among the community, and the imposed restrictions created hindrance for initiating interactions with outsiders in the sites. The unavailability of hospital beds for COVID patients during the COVID peak resulted in non-cooperation of the community with the research team.

- Distrust for COVID-19 vaccination: Communities, particularly rural and tribal communities, were reluctant to accept COVID-19 vaccination. They were panic-stricken and agitated at the prospect of engaging with people working in the health sector or associated with hospitals. There was also resistance among communities against the implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures, such as social distancing and following COVID norms. Dissatisfaction with suboptimal functioning of primary care facilities during the pandemic, reduced staffing, and services as a result of the pandemic were a major issue faced by the surveillance team.

- Unpleasant past experiences: Some of the community members had unpleasant experience of supporting governmental or non-governmental activities in the past, resulting in non-cooperation. For instance, no personal benefits were received by the community members for previous participation in other surveillance activities. Some community members had unpleasant experiences of not receiving any financial or other benefits promised to them for their participation in prior community-based research activities conducted in their areas, which further compounded their unwillingness to participate in the present research project.

- Engagement of locally hired people in the enumeration team may bring undue demands and interference from the local community, such as mounting pressure to hire undeserving candidates, negotiations for the payment amount or rolling back the termination order, etc.

- (B)

- Enablers to achieve CE: Many enabling factors were noticed that facilitated CE, which are described below.

- Pre-existing community links with the research teams by virtue of being the field practice areas of the respective institutions; b. broadcasts of the activities conducted by the SOMAARTH DDESS among the public by the village council through the public announcement system; c. involvement and engagement of community-level frontline health workers (ASHA, Anganwadi workers); and d. involvement of village volunteers were helpful in ensuring community engagement activities.

- (C)

- Strategies adopted for better community engagement: In view of the existing barriers, challenges and enablers, various site-specific strategies were undertaken in order to achieve better community engagement (Table 2).

- Formation of a community advisory board (CAB) at each DDESS site: Each study site formed a CAB by identifying and recruiting significant stakeholders following a common CAB charter for better functioning of the DDESS site. Meetings among the members of the advisory committee were held to identify and address existing community-level issues to achieve trust and better community involvement and participation. The CAB helps in supporting advocacy, sensitization campaigns related to the project, and mitigation of any conflict, while ensuring that beliefs and cultural disparities among community members are respected. The CAB gives advice and recommendations to the research team but has no administrative or legal responsibilities. The research team informs the CAB before carrying out any new activities. The board provides guidance and assistance in planning and implementing the activities of the project by ensuring that the activities are conducted in an informed and transparent manner that is acceptable to the community.

- Identifying and involving community volunteers: Some of the DDESS sites identified and involved local community volunteers, such as Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) members, schoolteachers, ASHA, Anganwadi workers, etc. These community volunteers were engaged during the community mobilization process. They provided enormous support during community consultation, village boundary mapping, and for health awareness initiatives towards strengthening surveillance activity. In order to avoid the interference of the community in the recruitment and research processes, a detailed SOP for the village volunteers’ recruitment was developed and followed by the sites. The formal recruitment process for the engagement of village volunteers included vacancy announcements in all the site villages/localities, organization of written examinations and tablet tests at clusters for ensuring the participation of volunteers from the villages which are far from the office location, followed by face-to-face interviews with the successful candidates. A merit list was prepared and publicly displayed for the transparency of the process and recruitment of the village volunteers was carried out on the basis of the merit list.

- Community consultations involving key stakeholders: Prior to data collection, the population was consulted and appraised of the project objectives. During the meetings, key stakeholders, such as local health care providers, schoolteachers, and community leaders were also involved. Many stakeholders played a role as a link between the community and researchers. This improved the trust among the people to participate and support the project’s activities.

- Undertaking other health-related activities: Apart from the project-related activities, the DDESS sites also organized some other health initiatives, such as health camps, COVID-19 Serosurveys, screening for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and oral health problems. Community awareness and sensitization programs based on prevailing key health issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic situation, prenatal/postnatal care, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), and vector-borne diseases, such as dengue, chikungunya, etc., were supported by the community stakeholders.

- The participatory mapping and data collection approach helped in gathering updated relevant information in the manner in which the community perceived them. In villages where boundaries were not available in the government census maps, research teams were able to gather information through the community consultation process.

| Factors | MAMC, New Delhi | SAS, New Delhi | INCLEN, Shillong | RMRC, Bhubaneswar | AMC, Andhra Pradesh | PIMS, Puducherry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers encountered | ||||||

| Language barrier | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Poor road connectivity and difficult terrain | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Inclement weather and extreme climate conditions | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Expectation of financial benefits | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fear of wage loss | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dispute over land ownership | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pandemic and fear of COVID-19 infection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Distrust of COVID-19 vaccination | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Unpleasant past experiences | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Community interference | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Enablers | ||||||

| Pre-existing community links | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Broadcast of activities | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Involvement and engagement of frontline health workers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Involvement of village volunteers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Strategies adopted | ||||||

| Formation of community advisory board (CAB) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Identifying and involving community volunteers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community consultations involving key stakeholders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Undertaking other health-related activities (screening camps, serosurveys, etc.) | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Participatory mapping | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Village Volunteer recruitment SOP | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Communication strategy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Provenance and Peer Review

References

- SOMAARTH-I Demographic Development and Environment Surveillance Site (DDESS): Key Indicators (Fact Sheet). Available online: http://somaarth.org/demographic-surveillance/ (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- About Us—SOMAARTH-DDESS, Aurangabad, Palwal. Available online: http://somaarth.org/about-us/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- 9th Annual Report—BIRAC. Available online: https://birac.nic.in/webcontent/BIRAC_Annual_Report_2020_21_English.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Ghosh, S.; Barik, A.; Majumder, S.; Gorain, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Mazumdar, S.; Chatterjee, K.; Bhaumik, S.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.K.; Satpathi, B.; et al. Health & demographic surveillance system profile: The Birbhum population project (Birbhum HDSS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sie, A.; Louis, V.; Gbangou, A.; Müller, O.; Niamba, L.; Stieglbauer, G.; Ye, M.; Kouyate, B.; Sauerborn, R.; Becher, H. The health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) in Nouna, Burkina Faso, 1993–2007. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossier, C.; Soura, A.; Baya, B.; Compaoré, G.; Dabiré, B.; Dos Santos, S.; Duthé, G.; Gnoumou, B.; Kobiané, J.F.; Kouanda, S.; et al. Profile: The Ouagadougou health and demographic surveillance system. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiden, F.; Hodgson, A.; Binka, F.N. Demographic Surveillance Sites and emerging challenges in international health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2006, 84, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.J. Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems and the 2030 Agenda: Sustainable Development Goals. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.03910. [Google Scholar]

- Nhacolo, A.; Jamisse, E.; Augusto, O.; Matsena, T.; Hunguana, A.; Mandomando, I.; Arnaldo, C.; Munguambe, K.; Macete, E.; Alonso, P.; et al. Cohort profile update: Manhiça health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) of the Manhiça health research centre (CISM). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngugi, A.K.; Odhiambo, R.; Agoi, F.; Lakhani, A.; Orwa, J.; Obure, J.; Mang’ong’o, D.; Luchters, S.; Munywoki, C.; Omar, A.; et al. Cohort profile: The Kaloleni/Rabai community health and demographic surveillance system. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 758–759e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newtonraj, A.; Purty, A.J.; Vincent, A.; Manikandan, M.; Bazroy, J.; Konduru, R.K.; Natesan, M. The chunampet community health information management system: A health and demographic surveillance system from a rural South India. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, S.; Arora, N.K.; Rahman, A.; Howard, N.J.; Singh, R.K.; Vaswani, M.; Das, M.K.; Ahmed, F.; Mathur, P.; Tandon, N.; et al. Establishing a demographic, development and environmental geospatial surveillance platform in India: Planning and implementation. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018, 4, e9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, N.J.; Dixit, S.; Naqvi, H.R.; Rahman, A.; Paquet, C.; Daniel, M.; Arora, N.K. Evaluation of data accuracies within a comprehensive geospatial-health data surveillance platform: SOMAARTH Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Site, Palwal, Haryana, India. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 2018, 3, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, S.; Misra, P.; Gupta, S.; Goswami, K.; Krishnan, A.; Nongkynrih, B.; Rai, S.K.; Srivastava, R.; Pandav, C.S. The Ballabgarh health and demographic surveillance system (CRHSP-AIIMS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.; Roy, S.; Ingole, V.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Chaudhary, B.; Lele, P.; Hirve, S.; Juvekar, S. Profile: Vadu health and demographic surveillance system Pune, India. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Disease Control. Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd ed.; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, H.B.; Solomon, R.; Bisrat, F.; Hilmi, L.; Stamidis, K.V.; Steinglass, R.; Weiss, W.; Losey, L.; Ogden, E. Lessons learned from the CORE Group Polio Project and their relevance for other global health priorities. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101 (Suppl. 4), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyril, S.; Smith, B.J.; Possamai-Inesedy, A.; Renzaho, A.M. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: A systematic review. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 29842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, E.Z.; Bandewar, S.V.; Boulanger, R.F.; Mehta, R.; Lin, T.; Vincent, R.; Molyneux, S.; Goldstone, A.; Lavery, J.V. Addressing diversity and complexity in the community engagement literature: The rationale for a realist review. Welcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, J.S.; Jaswal, N.; Grover, A. Is focus on prevention missing in national health programs? A situation analysis of IEC/BCC/health promotion activities in a district setting of Punjab and Haryana. Indian J. Commun. Med. 2017, 42, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.M.; Collinson, M.A.; Clark, S.J.; Twine, R.; Clark, B.D.; Shabangu, M.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Mokoena, O.; Garenne, M.L. Research into health, population and social transitions in rural South Africa: Data and methods of the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System1. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 35 (Suppl. 69), 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minimum Quality Standards and Indicators in Community Engagement. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mena/reports/community-engagement-standards (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Gilmore, B.; Ndejjo, R.; Tchetchia, A.; de Claro, V.; Mago, E.; A Diallo, A.; Lopes, C.; Bhattacharyya, S. Community engagement for COVID-19 prevention and control: A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, P.; Nwanyanwu, O.; Nkengasong, J.N.; Mukanga, D.; Trostle, M. Strengthening public health surveillance and response using the health systems strengthening agenda in developing countries. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wamukoya, M.; Ezeh, A.; Emina, J.B.; Sankoh, O. Health and demographic surveillance systems: A step towards full civil registration and vital statistics system in sub-Sahara Africa? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedini, S.A.; Thaele, D.; Sello, M.; Mutevedzi, P.; Hywinya, C.; Ngwenya, N.; Myburgh, N.; Madhi, S.A. Approaches, achievements, challenges, and lessons learned in setting up an urban-based Health and Demographic Surveillance System in South Africa. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1874138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, S.D.; Andrews, J.O.; Magwood, G.S.; Jenkins, C.; Cox, M.J.; Williamson, D.C. Peer reviewed: Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A70. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, A.; Piccione, C.; Fisher, A.; Matt, K.; Andreini, M.; Bingham, D. Survey development: Community-involvement in the design and implementation process. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. JPHMP 2019, 25 (Suppl. 5), S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, S.; McAlvain, M.S.; Briant, K.J.; Hohl, S.; Thompson, B. Perspectives of community advisory board members in a community-academic partnership. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightfoot, E.; McCleary, J.S.; Lum, T. Asset mapping as a research tool for community-based participatory research in social work. Soc. Work. Res. 2014, 38, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Checkoway, B.; Schulz, A.; Zimmerman, M. Health education and community empowerment: Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Educ. Q. 1994, 21, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkins, S.; Carlisle, K.; Harrington, H.; MacLaren, D.; Lovo, E.; Harrington, R.; Fernandes Alves, L.; Rafai, E.; Delai, M.; Whittaker, M. From the frontline: Strengthening surveillance and response capacities of the rural workforce in the Asia-Pacific region. How can grass-roots implementation research help? Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, V.; Lagarde, M.; Batura, N.; Lin, S.; Irava, W.; Roberts, G. Measuring inequalities in the distribution of the Fiji Health Workforce. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, N.; Palo, S.K.; Bhimarasetty, D.M.; Kandipudi, K.L.P.; Purty, A.J.; Kumar, T.; Basu, S.; Alice, A.; Velavan, A.; Madhavan, S.; et al. Community Dynamics and Engagement Strategies in Establishing Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Systems: A Multi-Site Report from India. Healthcare 2023, 11, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030411

Sharma N, Palo SK, Bhimarasetty DM, Kandipudi KLP, Purty AJ, Kumar T, Basu S, Alice A, Velavan A, Madhavan S, et al. Community Dynamics and Engagement Strategies in Establishing Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Systems: A Multi-Site Report from India. Healthcare. 2023; 11(3):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030411

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Nandini, Subrata Kumar Palo, Devi Madhavi Bhimarasetty, Kesava Lakshmi Prasad Kandipudi, Anil J. Purty, Tivendra Kumar, Saurav Basu, Alice Alice, A. Velavan, Sathish Madhavan, and et al. 2023. "Community Dynamics and Engagement Strategies in Establishing Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Systems: A Multi-Site Report from India" Healthcare 11, no. 3: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030411

APA StyleSharma, N., Palo, S. K., Bhimarasetty, D. M., Kandipudi, K. L. P., Purty, A. J., Kumar, T., Basu, S., Alice, A., Velavan, A., Madhavan, S., Rongsen-Chandola, T., Arora, N. K., Dixit, S., Pati, S., & Taneja Malik, S. (2023). Community Dynamics and Engagement Strategies in Establishing Demographic Development and Environmental Surveillance Systems: A Multi-Site Report from India. Healthcare, 11(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030411