Awareness of Medical Professionals Regarding Research Ethics in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Survey to Assess Training Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

Specific Objectives

- To assess research ethics awareness among medical professionals and researchers.

- To explore and assess the awareness and training needs pertaining to international and national regulations on research ethics, the fundamental principles of medical research ethics, ethical issues, and practical implementations of research ethics across various research methodologies (genetic, qualitative, quantitative, and clinical trials), the significance of informed consent, and Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight.

- To compare the research ethics awareness and training needs among different professional groups, including physicians, nurses, and researchers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Variables

- Socio-demographic data: The initial section of the questionnaire was designed to gather socio-demographic data from the participants, which included personal information about the participants’ social status, demographic status, educational, and research background.

- Regulations: This section was intended to gather data about the level of awareness of regulatory texts. The survey in this study utilized a Likert-type scale consisting of three response options.

- Principles: This section sought to gather data on the level of awareness pertaining to different research principles. The survey utilized a 4-point Likert-type scale, where respondents were asked to rate the importance of the items on a scale ranging from 1 (indicating low importance) to 4 (indicating high importance).

- Ethical challenges: This 3-point Likert scale survey was aimed at collecting information about their level of awareness about ethical challenges in several types of research designs.

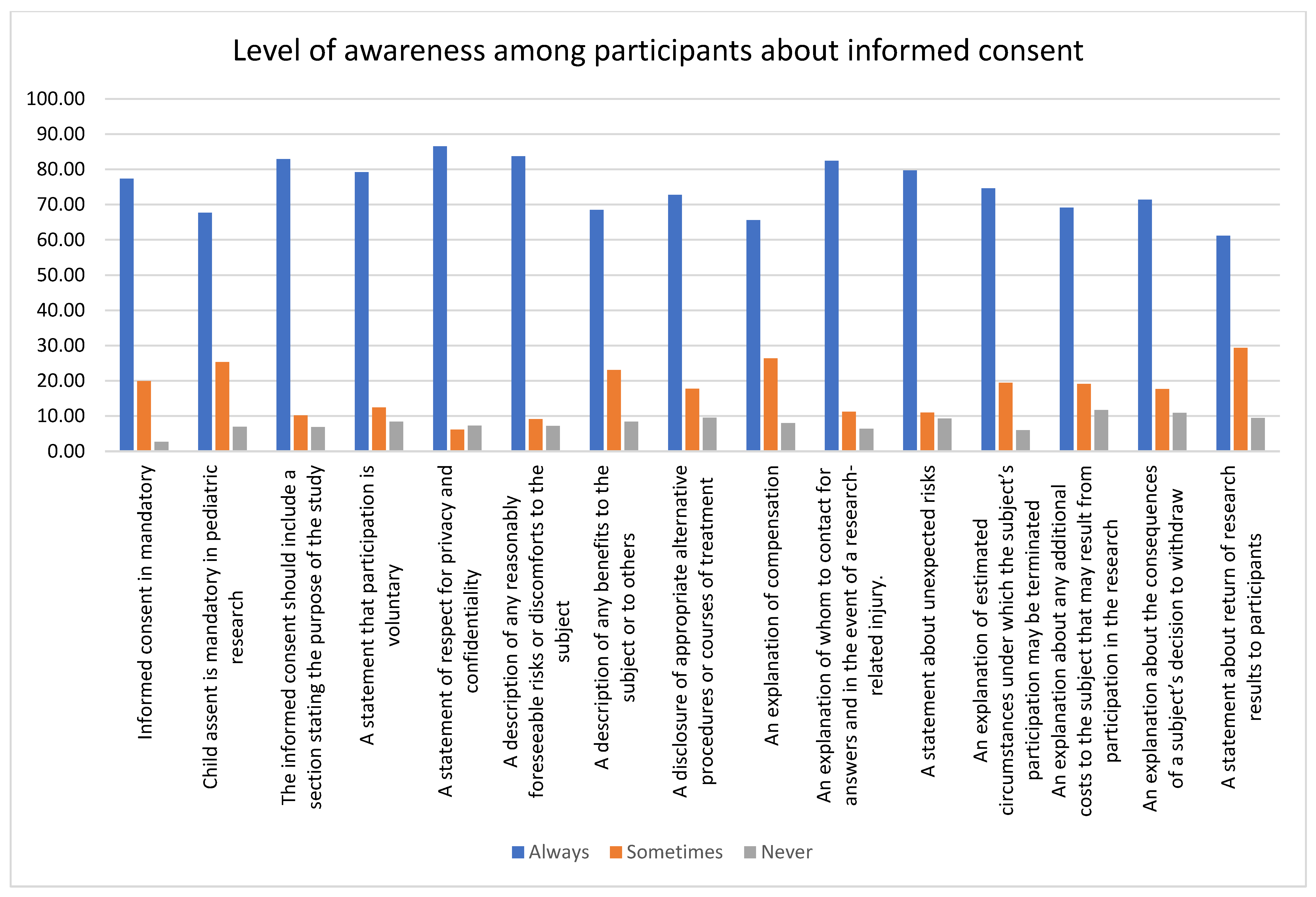

- Informed consent: In this section, participants were requested to ascertain whether some aspects of informed consent are always, sometimes, or never true.

- IRB: This is a 5-point Likert-type survey, where respondents indicate their level of agreement on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this section, participants were asked to determine whether they strongly agree, agree, are neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree with the listed information about the IRB.

2.5. Data Sources and Measurements

2.6. Bias

2.7. Study Size

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Awareness of Key International and Local Regulatory Texts Guiding the Protection of Human Research Participants

3.4. Attitude toward the Existence, Significance, and Capacity to Implement Key Principles Guiding the Protection of Human Research Subjects

3.5. Awareness among Respondents of the Existence of Ethical Issues in Several Types of Research

3.6. Knowledge of Physicians, Nurses, and Researchers Regarding Informed Consent and Its Usage

3.7. Respondents’ Awareness of the Existence and Significance of the IRB Statements

4. Discussion

4.1. Training and Education on Research Ethics among Participants

4.2. Awareness of Key International and Local Regulatory Guidelines

4.3. Attitude toward the Key Principles Guiding the Protection of Human Research Subjects

4.4. Awareness of Ethical Issues in Several Types of Research

4.5. Knowledge of Informed Consent and Its Usage

4.6. Knowledge of the Existence and Significance of IRB Statements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkhunaizi, A.N.; Alhamidi, S.A. Ethics in nursing research. Saudi J. Nurs. Health Care 2023, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Acharya, S.; Parija, S.C. Ethics in human research. Trop. Parasitol. 2011, 1, 72105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. Bull. Med. Ethics 2002, 182, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Guideline, I.H. Guideline for good clinical practice. J. Postgrad. Med. 2001, 47, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmad, G.; Al-Jumah, M.; Dierickx, K. Review of national research ethics regulations and guidelines in Middle Eastern Arab countries. BMC Med. Ethics. 2012, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, G. National Guidelines Regarding Research Ethics in the Arab Countries: An Overview. In Research Ethics in the Arab Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, G. The Saudi Law of Ethics of Research on Living Creatures and its implementing regulations. Dev. World Bioeth. 2017, 17, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, G. National Guidelines Regarding Research Ethics in Saudi Arabia. In Research Ethics in the Arab Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, G.; Silverman, H. Research Ethics Governance in the Arab Region–Saudi Arabia. In Research Ethics in the Arab Region; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, S.; Hashan, H.; Al Hatareshah, A.; Al Ghamdi, A.; Al Shahwan, K. Regulating clinical trials in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Clin. Res. Clin. Trials Regul. Aff. 2014, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tannir, M.A.; Katan, H.M.; Al-Badr, A.H.; Al-Tannir, M.M.; Abu-Shaheen, A.K. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and perceptions of clinicians towards conducting clinical trials in an Academic Tertiary Care Center. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolfotouh, M.A.; Adlan, A.A. Quality of informed consent for invasive procedures in central Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2012, 5, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alahmad, G.; Hifnawy, T.; Abbasi, B.; Dierickx, K. Attitudes toward medical and genetic confidentiality in the Saudi research biobank: An exploratory survey. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 87, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, H.; Pickering, L. New directions in qualitative research ethics. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zyphur, M.J.; Pierides, D.C. Is Quantitative Research Ethical? Tools for Ethically Practicing, Evaluating, and Using Quantitative Research. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Tang, Q. The ethics of COVID-19 clinical trials: New considerations in a controversial area. Integr. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Summer School. Available online: https://rss.kaimrc.med.sa/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Clinical Research Training|King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre. Available online: https://www.kfshrc.edu.sa/en/home/education/ugme/clinicalresearchtraining (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Sivasubramaniam, S.; Dlabolová, D.H.; Kralikova, V.; Khan, Z.R. Assisting you to advance with ethics in research: An introduction to ethical governance and application procedures. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2021, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 2.3.1. Updated 6 April 2013. Available online: www.OpenEpi.com (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- SAS Institute. STAT-SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, H.B.; Arici, M.A.; Ucku, R.; Gelal, A. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and opinions towards clinical research: A cross-sectional study in a University hospital. J. Basic Clin. Health Sci. 2018, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, D.H.; Alsinaidi, A.A.; Alshaalan, N.S.; Aljuanydil, N.A. Dental researchers’ knowledge, awareness and attitudes on the ethics and ethics committees at different Saudi Arabian universities. A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Med. Dent. 2021, 25, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Aldarwesh, A.Q. Perception of research ethics amongst Saudi postgraduate students: Compararsion between home and abroad academic environment. Oxf. Res. J. 2013, 3, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Azakir, B.; Mobarak, H.; Al Najjar, S.; El Naga, A.A.; Mashaal, N. Knowledge and attitudes of physicians toward research ethics and scientific misconduct in Lebanon. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, K.; Katashima, R.; Miyamoto, T.; Yoshimaru, M.; Takai, S.; Yanagawa, H. Nurse awareness of clinical research: A survey in a Japanese University Hospital. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.R.; Lantz, J.M.; Fullerton, J.T.; Dault, Y. Nurses’ unique roles in randomized clinical trials. J. Prof. Nurs. 1999, 15, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alardan, A.; Alshammari, S.A.; Alruwaili, M. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of family medicine trainees in Saudi training programs towards medical ethics, in Riyadh. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2021, 10, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazrou, D.A.; Ali, S.; Al-Abdulkarim, D.A.; Albalawi, A.F.; Alzhrani, J.A. Information seeking behavior and awareness among physicians regarding drug information centers in Saudi Arabia. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Demour, S.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Alabsi, A.; Al Abdallat, S.; Alzayed, A. Knowledge, awareness, and attitudes about research ethics committees and informed consent among resident doctors. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2019, 12, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Martin, M.Y.; Fouad, M.N.; Vickers, S.M.; Wenzel, J.; Cook, E.D.; Konety, B.R.; Durant, R.W. Bias and stereotyping among research and clinical professionals: Perspectives on minority recruitment for oncology clinical trials. Cancer 2020, 126, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.S. A study on awareness and practices of bio-medical waste management in tertiary care hospital. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2021, 15, 2075–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjari, M.; Bahramnezhad, F.; Fomani, F.K.; Shoghi, M.; Cheraghi, M.A. Ethical challenges of researchers in qualitative studies: The necessity to develop a specific guideline. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2014, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, L. Explaining the role of the nurse in clinical trials. Nurs. Stand. 2011, 25, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, B. Informed consent in research. Eur. Health Psychol. 2014, 16, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- McElfish, P.A.; Purvis, R.S.; Long, C.R. Researchers’ experiences with and perceptions of returning results to participants: Study protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 11, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.H.; Mapes, B.M.; Jerome, R.N.; Villalta-Gil, V.; Pulley, J.M.; Harris, P.A. Understanding what information is valued by research participants, and why. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, C. Institutional review boards: Purpose and challenges. Chest 2015, 148, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajab, M.H.; Alkawi, M.Z.; Gazal, A.M.; Alshehri, F.A.; Shaibah, H.S.; Holmes, L.D. Evaluation of a university’s Institutional Review Board based on campus feedback: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2019, 11, e5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlFattani, A.; AlBedah, N.; AlShahrani, A.; Alkawi, A.; AlMeharish, A.; Altwaijri, Y.; Omar, A.; AlKawi, M.Z.; Khogeer, A. Institutional review boards in Saudi Arabia: The first survey- Based report on their functions and operations. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, R.D.; Abbott, L.J.; Wichman, A. Nonscientist IRB members at the NIH. IRB 2008, 30, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, S.; Aalborg, A.; Basagoitia, A.; Cortes, J.; Lanza, O.; Schwind, J.S. Exploring perceptions and experiences of Bolivian health researchers with research ethics. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2015, 10, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gaai, E.A.; Hammami, M.M.; Al Eidan, M. Documentation of ethical conduct of human subject research published in Saudi medical journals. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Jeong, G.H.; Shin, H.W.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, Y.; Bae, G.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Song, Y.M.; et al. Nursing Faculties’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Research Ethics According to Demographic Characteristics and Institutional Environment in Korea. SAGE Open. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.K.; Min, A. A Case-Centered Approach to Nursing Ethics Education: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nurses n = 114 | Physician n = 89 | Researchers n = 48 | Overall n = 251 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean ± S.D. | 34.50 ± 7.66 | 32.76 ± 10.09 | 36.80 ± 9.68 | 34.25 ± 9.07 |

| Gender n (%) | ||||

| Female | 104 (91.23) | 36 (40.91) | 22 (45.83) | 162 (64.54) |

| Male | 10 (8.77) | 52 (59.09) | 26 (54.17) | 88 (35.05) |

| Marital Status n (%) | ||||

| Single | 47 (41.23) | 38 (43.68) | 21 (44.68) | 106 (42.23) |

| Married | 65 (57.02) | 45 (51.72) | 24 (51.06) | 134 (53.39) |

| Divorced | 2 (1.75) | 4 (4.60) | 2 (4.26) | 8 (3.19) |

| Widow\er | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Having children n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 48 (42.11) | 39 (45.35) | 24 (51.06) | 111 (44.22) |

| Educational level n (%) | ||||

| Bachelor | 102 (91.89) | 55 (63.22) | 11 (22.92) | 168 (66.93) |

| Master | 9 (8.11) | 15 (17.24) | 10 (20.83) | 34 (13.55) |

| PhD | 0 | 17 (19.54) | 27 (56.25) | 44 (17.53) |

| Specialty | ||||

| Clinical | 12 (10.62) | 69 (83.13) | 10 (22.22) | 91 (36.25) |

| Basic Science | 0 | 14 (16.87) | 35 (77.78) | 49 (19.52) |

| Nursing | 101 (89.38) | 0 | 0 | 101 (40.24) |

| Training in research ethics n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 36 (31.86) | 61 (69.32) | 38 (79.17) | 135 (53.78) |

| Training type n (%) | ||||

| Internet-based | 2 (5.41) | 9 (14.29) | 2 (5.26) | 13 (9.62) |

| Workshop | 7 (18.92) | 9 (14.29) | 2 (5.26) | 18 (13.33) |

| During internship | 6 (16.22) | 4 (6.35) | 2 (5.26) | 12 (8.89) |

| In academic milieu | 11 (29.73) | 26 (41.27) | 8 (21.05) | 45 (33.33) |

| Others | 3 (8.11) | 2 (3.17) | 1 (2.63) | 6 (4.44) |

| More than one type | 8 (21.62) | 13 (20.63) | 23 (60.53) | 44 (32.59) |

| Satisfaction with training n (%) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 13 (36.11) | 20 (32.26) | 20 (52.63) | 53 (39.25) |

| Moderately satisfied | 16 (44.44) | 32 (51.61) | 16 (42.11) | 64 (47.41) |

| Less satisfied | 6 (16.67) | 7 (11.29) | 1 (2.63) | 14 (10.37) |

| Not satisfied | 1 (2.78) | 3 (4.84) | 1 (2.63) | 5 (3.70) |

| More training needed n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 29 (80.56) | 47 (77.05) | 30 (78.95) | 106 (78.51) |

| Want to receive training n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 44 (73.33) | 29 (85.29) | 11 (78.57) | 84 (72.41) |

| Research ethics in your program n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 28 (26.42) | 32 (37.21) | 26 (54.17) | 86 (34.26) |

| Topics taught n (%) | ||||

| Research Ethics | 8 (53.33) | 16 (69.57) | 7 (46.67) | 31 (36) |

| Non-research Ethics | 6 (40.00) | 4 (17.39) | 3 (20.00) | 13 (15.11) |

| Both | 1 (6.67) | 3 (13.04) | 5 (33.33) | 9 (10.46) |

| PI or Co-PI n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 7 (6.42) | 45 (52.33) | 28 (58.33) | 80 (31.87) |

| Nurses | Physicians | Researchers | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | ||

| Nuremberg Code | 96 (84.21) | 10 (8.77) | 8 (7.02) | 55 (64.71) | 18 (21.18) | 12 (14.12) | 24 (50.00) | 13 (27.08) | 11 (22.92) | 0.0002 †* |

| Declaration of Helsinki | 87 (76.32) | 16 (14.04) | 11 (9.65) | 46 (53.49) | 23 (26.74) | 17 (19.77) | 11 (22.92) | 19 (39.58) | 18 (37.50) | <0.0001 †* |

| International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research | 66 (58.41) | 32 (28.32) | 15 (13.27) | 27 (31.76) | 36 (42.35) | 22 (25.88) | 5 (10.42) | 16 (33.33) | 27 (56.25) | <0.0001 †* |

| Belmont Report | 98 (88.29) | 8 (7.21) | 5 (4.50) | 62 (73.81) | 16 (19.05) | 6 (7.14) | 26 (55.32) | 10 (21.28) | 11 (23.40) | <0.0001 †* |

| Good clinical practice (GCP) | 91 (79.82) | 15 (13.16) | 8 (7.02) | 47 (54.65) | 23 (26.74) | 16 (18.60) | 12 (25.53) | 22 (46.81) | 13 (27.66) | <0.0001 †* |

| Regulations of the Law of Ethics of Research on Living Creatures in Saudi Arabia | 90 (78.95) | 16 (14.04) | 8 (7.02) | 46 (54.12) | 23 (27.06) | 16 (18.82) | 18 (37.50) | 18 (37.50) | 12 (25.00) | <0.0001 †* |

| Saudi FDA Regulation | 48 (42.86) | 35 (31.25) | 29 (25.89) | 21 (24.42) | 33 (38.37) | 32 (37.21) | 3 (6.25) | 26 (54.17) | 19 (39.58) | <0.0001 †* |

| International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects-Islamic view | 80 (70.80) | 21 (18.58) | 12 (10.62) | 41 (48.24) | 24 (28.24) | 20 (23.53) | 16 (33.33) | 15 (31.25) | 17 (35.42) | <0.0001 †* |

| Nurses n (%) | Physicians n (%) | Researchers n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respecting human dignity | 111 (44.58) | 87 (34.94) | 45 (18.07) | 0.1399 ‡ |

| Benefit | 108 (43.55) | 85 (34.27) | 42 (16.94) | 0.0759 ‡ |

| Do no harm | 109(43.78) | 86 (34.54) | 44 (17.67) | 0.2763 ‡ |

| Respect of autonomy | 109 (44.31) | 83 (33.74) | 42 (17.07) | 0.0342 ‡* |

| Respect for human vulnerability | 108 (43.37) | 85 (34.14) | 46 (18.47) | 0.9183 ‡ |

| Respect privacy and confidentiality | 109 (43.78) | 86 (34.54) | 45 (18.07) | 0.5001 ‡ |

| Respect justice | 111 (44.58) | 85 (34.14) | 45 (18.07) | 0.1074 ‡ |

| Prevent discrimination | 108 (43.55) | 82 (33.06) | 44 (17.74) | 0.3406 ‡ |

| Prevent stigmatization | 108 (43.72) | 83 (33.60) | 42 (17.00) | 0.2201 ‡ |

| Respect for cultural diversity and pluralism | 109 (44.13) | 81 (32.79) | 43 (17.41) | 0.1018 ‡ |

| Respect for solidarity and cooperation | 109 (43.95) | 80 (32.26) | 42 (16.94) | 0.0337 ‡* |

| Respect for social responsibility and health | 107 (42.97) | 83 (33.33) | 45 (18.07) | 0.7661 ‡ |

| Respect for sharing of benefits | 109 (43) | 79 (33) | 43 (17) | |

| Protecting future generations | 108 (43.37) | 82 (32.93) | 45 (18.07) | 0.3924 ‡ |

| Protection of the environment, the biosphere and biodiversity | 108 (43.55) | 82 (33.06) | 44 (17.74) | 0.3406 ‡ |

| Nurses | Physicians | Researchers | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | Not Aware n (%) | Simple Aware n (%) | Fully Aware n (%) | ||

| Ethical issues in quantitative research | 43 (37.72) | 43 (37.72) | 28 (24.56) | 22 (25.00) | 39 (44.32) | 27 (30.68) | 5 (10.42) | 20 (41.67) | 23 (47.92) | 0.0026 ‡* |

| Ethical issues in qualitative research | 41 (36.28) | 41 (36.28) | 31 (27.43) | 22 (25.00) | 40 (45.45) | 26 (29.55) | 7 (14.58) | 17 (35.42) | 24 (50.00) | 0.0132 ‡* |

| Ethical issues in retrospective research | 50 (44.25) | 44 (38.94) | 19 (16.81) | 22 (25.00) | 32 (36.36) | 34 (38.64) | 8 (16.67) | 18 (37.50) | 22 (45.83) | <0.0001 ‡* |

| Ethical issues in clinical trials and interventional studies | 44 (39.29) | 46 (41.07) | 22 (19.64) | 17 (19.32) | 37 (42.05) | 34 (38.64) | 4 (8.33) | 18 (37.50) | 26 (54.17) | <0.0001 ‡* |

| Ethical issues in genetic research | 53 (46.90) | 42 (37.17) | 18 (15.93) | 23 (26.44) | 37 (42.53) | 27 (31.03) | 4 (8.33) | 20 (41.67) | 24 (50.00) | <0.0001 ‡* |

| Ethical issues in vulnerable populations | 55 (48.67) | 38 (33.63) | 20 (17.70) | 25 (28.41) | 34 (38.64) | 29 (32.95) | 9 (18.75) | 19 (39.58) | 20 (41.67) | 0.0006 ‡* |

| Nurses | Physicians | Researchers | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Never n (%) | Always n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Never n (%) | Always n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Never n (%) | ||

| Informed consent is mandatory | 100 (88.50) | 11 (9.73) | 2 (1.77) | 64 (72.73) | 24 (27.27) | 0 (0.00) | 34 (70.83) | 11 (22.92) | 3 (6.25) | 0.0010 ‡* |

| Child assent is mandatory in pediatric research | 84 (74.34) | 25 (22.12) | 4 (3.54) | 54 (62.79) | 28 (32.56) | 4 (4.65) | 31 (65.96) | 10 (21.28) | 6 (12.77) | 0.0889 ‡ |

| The informed consent should include a section stating the purpose of the study | 100 (88.50) | 10 (8.85) | 3 (2.65) | 75 (85.23) | 10 (11.36) | 3 (3.41) | 36 (75.00) | 5 (10.42) | 7 (14.58) | 0.0540 ‡* |

| A statement that participation is voluntary | 99 (87.61) | 11 (9.73) | 3 (2.65) | 67 (77.01) | 13 (14.94) | 7 (8.05) | 35 (72.92) | 6 (12.50) | 7 (14.58) | 0.0446 ‡* |

| A statement of respect for privacy and confidentiality | 102 (90.27) | 7 (6.19) | 4 (3.54) | 78 (88.64) | 7 (7.95) | 3 (3.41) | 38 (80.85) | 2 (4.26) | 7 (14.89) | 0.0853 ‡ |

| A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject | 98 (86.73) | 11 (9.73) | 4 (3.54) | 75 (85.23) | 10 (11.36) | 3 (3.41) | 38 (79.17) | 3 (6.25) | 7 (14.58) | 0.0942 ‡ |

| A description of any benefits to the subject or to others | 96 (84.96) | 10 (8.85) | 7 (6.19) | 62 (70.45) | 22 (25.00) | 4 (4.55) | 24 (50.00) | 17 (35.42) | 7 (14.58) | <0.0001 ‡* |

| A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment | 97 (85.84) | 10 (8.85) | 6 (5.31) | 67 (76.14) | 17 (19.32) | 4 (4.55) | 27 (56.25) | 12 (25.00) | 9 (18.75) | 0.0006 ‡* |

| An explanation of compensation | 90 (79.65) | 14 (12.39) | 9 (7.96) | 58 (65.17) | 26 (29.21) | 5 (5.62) | 25 (52.08) | 18 (37.50) | 5 (10.42) | 0.0026 †* |

| An explanation of whom to contact for answers in the event of a research-related injury | 98 (86.73) | 9 (7.96) | 6 (5.31) | 78 (87.64) | 8 (8.99) | 3 (3.37) | 35 (72.92) | 8 (16.67) | 5 (10.42) | 0.1766 ‡ |

| A statement about unexpected risks | 97 (85.84) | 11 (9.73) | 5 (4.42) | 66 (74.16) | 15 (16.85) | 8 (8.99) | 38 (79.17) | 3 (6.25) | 7 (14.58) | 0.0608 † |

| An explanation of estimated circumstances under which the subject’s participation may be terminated | 94 (82.46) | 13 (11.40) | 7 (6.14) | 72 (80.90) | 14 (15.73) | 3 (3.37) | 29 (60.42) | 15 (31.25) | 4 (8.33) | 0.0204 ‡* |

| An explanation about any additional costs to the subject that may result from participation in the research | 93 (81.58) | 15 (13.16) | 6 (5.26) | 62 (69.66) | 19 (21.35) | 8 (8.99) | 27 (56.25) | 11 (22.92) | 10 (20.83) | 0.0060 †* |

| An explanation about the consequences of a subject’s decision to withdraw | 93 (81.58) | 14 (12.28) | 7 (6.14) | 68 (76.40) | 14 (15.73) | 7 (7.87) | 27 (56.25) | 12 (25.00) | 9 (18.75) | 0.0141 †* |

| A statement about the return of research results to participants | 92 (80.70) | 17 (14.91) | 5 (4.39) | 55 (62.50) | 25 (28.41) | 8 (9.09) | 19 (40.43) | 21 (44.68) | 7 (14.89) | <0.0001 †* |

| Nurses n (%) | Physicians n (%) | Researchers n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every research should be evaluated by the IRB | 87 (76.32) | 78 (88.64) | 31 (64.58) | 196 (78.57) | <0.0001 †* |

| Every research should be evaluated by the full board | 87 (76.32) | 54 (62.07) | 17 (35.42) | 158 (63.35) | <0.0001 †* |

| The IRB chairman can approve research proposals without referring them to the full board | 53 (46.49) | 38 (43.18) | 23 (47.92) | 114 (45.24) | 0.0186 †* |

| The IRB can approve, disapprove, or ask for modifications | 84 (73.68) | 75 (85.23) | 38 (79.17) | 197 (78.97) | 0.1403 ‡ |

| Five members be available during each meeting | 79 (69.30) | 34 (39.08) | 28 (58.33) | 141 (56) | 0.0004 †* |

| One member has knowledge of research methods | 68 (59.65) | 64 (73.56) | 35 (72.92) | 167 (66.93) | 0.0803 † |

| One member has knowledge of bioethics | 65 (74.71) | 65 (74.71) | 37 (77.08) | 174 (69.72) | 0.2390 † |

| One member be specialized in the medical field | 79 (69.91) | 69 (80.23) | 32 (66.67) | 180 (72.69) | 0.0474 †* |

| The IRB should have an unaffiliated member (non-medical person) | 73 (64.04) | 48 (55.17) | 23 (47.92) | 144 (57.77) | 0.3464 † |

| One member should be aware of the local culture | 85 (74.56) | 71 (81.61) | 35 (72.92) | 191 (76.89) | 0.5203 † |

| The IRB should have two genders | 79 (69.91) | 39 (44.83) | 24 (50.00) | 142 (57.2) | 0.0014 †* |

| The IRB should avoid any conflict of interest | 88 (79.28) | 75 (86.21) | 40 (83.33) | 203 (82.25) | 0.0005 ‡* |

| It is the responsibility of the IRB to review and evaluate the scientific design and conduct of the research | 87 (76.99) | 66 (75.86) | 28 (58.33) | 181 (73.2) | 0.0079 †* |

| It is the IRB responsibility to review and evaluate the confidentiality issues in research | 89 (78.76) | 73 (83.91) | 38 (79.17) | 200 (80.8) | 0.5268 † |

| It is the IRB responsibility to review and evaluate the contents of the informed consent | 87 (77.68) | 73 (83.91) | 41 (85.42) | 201 (81.52) | 0.4500 ‡ |

| It is the IRB responsibility to review and evaluate the process of collecting informed consent | 88 (78.57) | 67 (77.01) | 38 (79.17) | 193 (78.32) | 0.0412 †* |

| It is the IRB responsibility to take into account the community considerations | 86 (76.11) | 67 (77.01) | 34 (70.83) | 187 (75.6) | 0.7977 † |

| It is the IRB responsibility to review and evaluate the care and protection of research participants | 88 (77.88) | 73 (83.91) | 40 (83.33) | 201 (80.8) | 0.8522 ‡ |

| It is the IRB responsibility to review and evaluate the recruitment of research participants | 88 (77.88) | 65 (75.58) | 33 (68.75) | 186 (75.1) | 0.7158 † |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alahmad, G.; Alshahrani, K.M.; Alduhaim, R.A.; Alhelal, R.; Faden, R.M.; Shaheen, N.A. Awareness of Medical Professionals Regarding Research Ethics in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Survey to Assess Training Needs. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202718

Alahmad G, Alshahrani KM, Alduhaim RA, Alhelal R, Faden RM, Shaheen NA. Awareness of Medical Professionals Regarding Research Ethics in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Survey to Assess Training Needs. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202718

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlahmad, Ghiath, Khalid Malawi Alshahrani, Renad Abdulaziz Alduhaim, Rawan Alhelal, Rawa M. Faden, and Naila A. Shaheen. 2023. "Awareness of Medical Professionals Regarding Research Ethics in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Survey to Assess Training Needs" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202718

APA StyleAlahmad, G., Alshahrani, K. M., Alduhaim, R. A., Alhelal, R., Faden, R. M., & Shaheen, N. A. (2023). Awareness of Medical Professionals Regarding Research Ethics in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Survey to Assess Training Needs. Healthcare, 11(20), 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202718