Designing Categories for a Mixed-Method Research on Competence Development and Professional Identity through Collegial Advice in Nursing Education in Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Methods

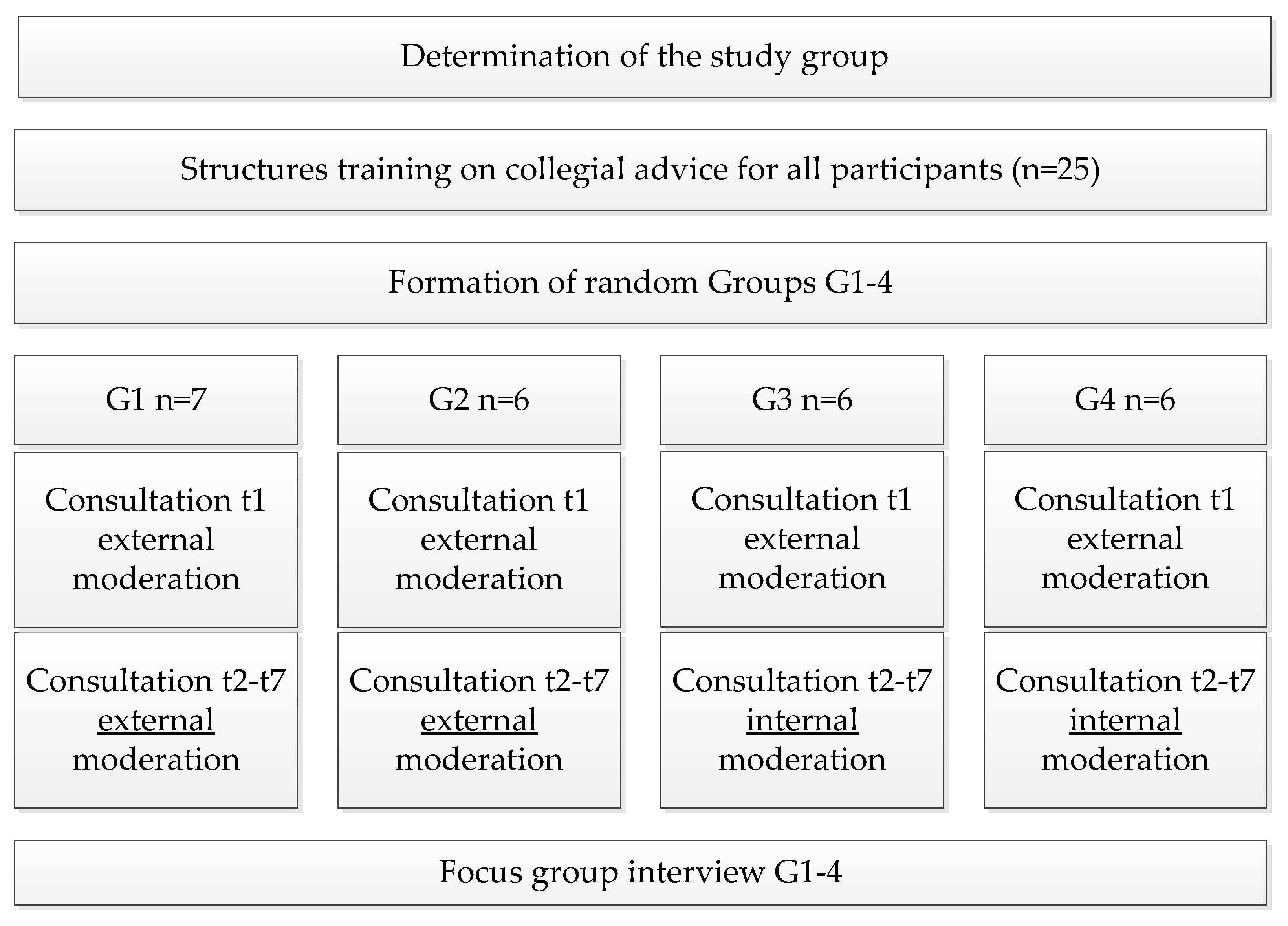

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Data Collection

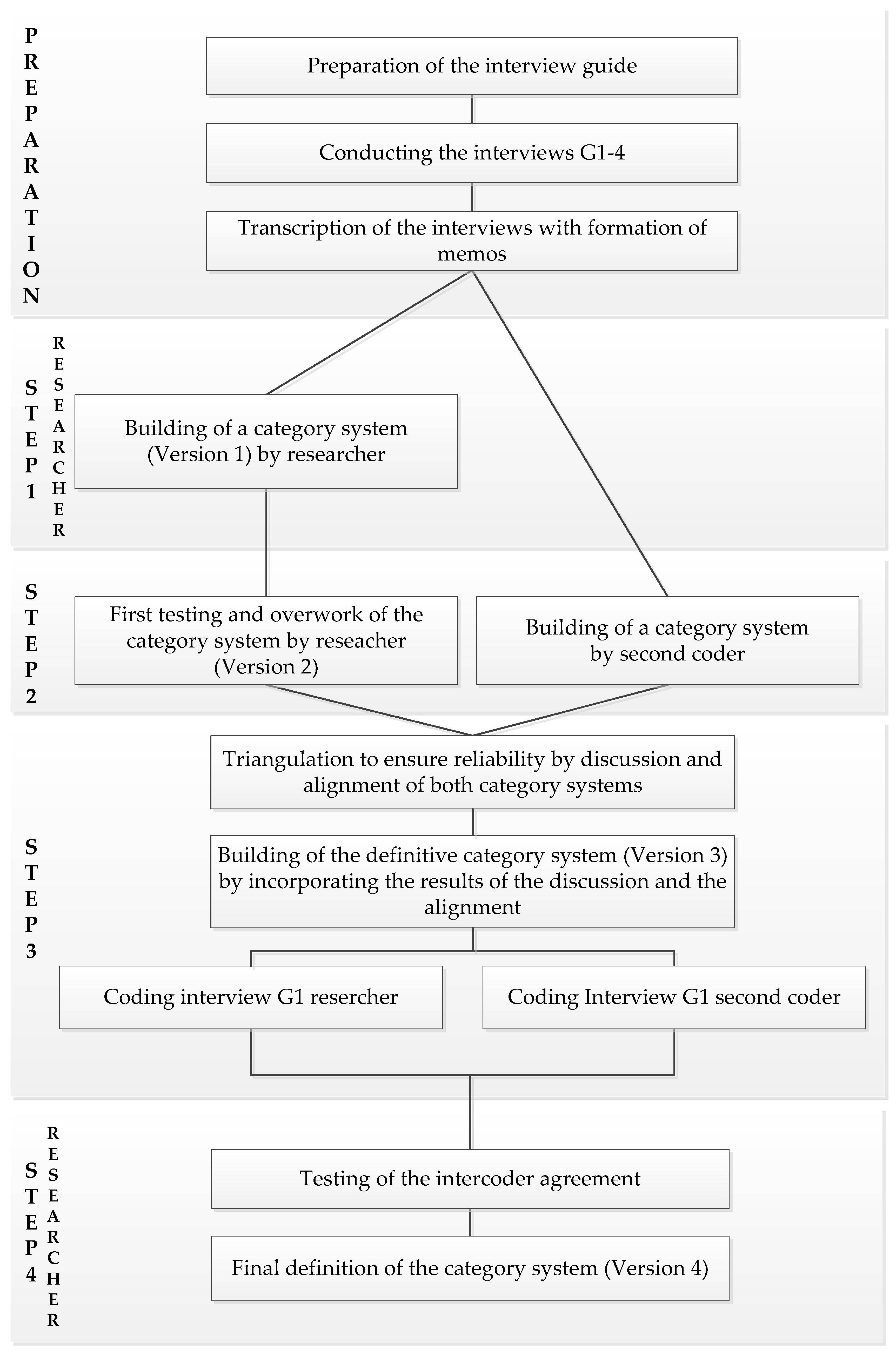

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Data Analysis

- Step 1: Deductive category formation

- Step 2: First testing of the category system

- Step 3: Triangulation to ensure reliability

- Step 4: testing of the intercoder reliability

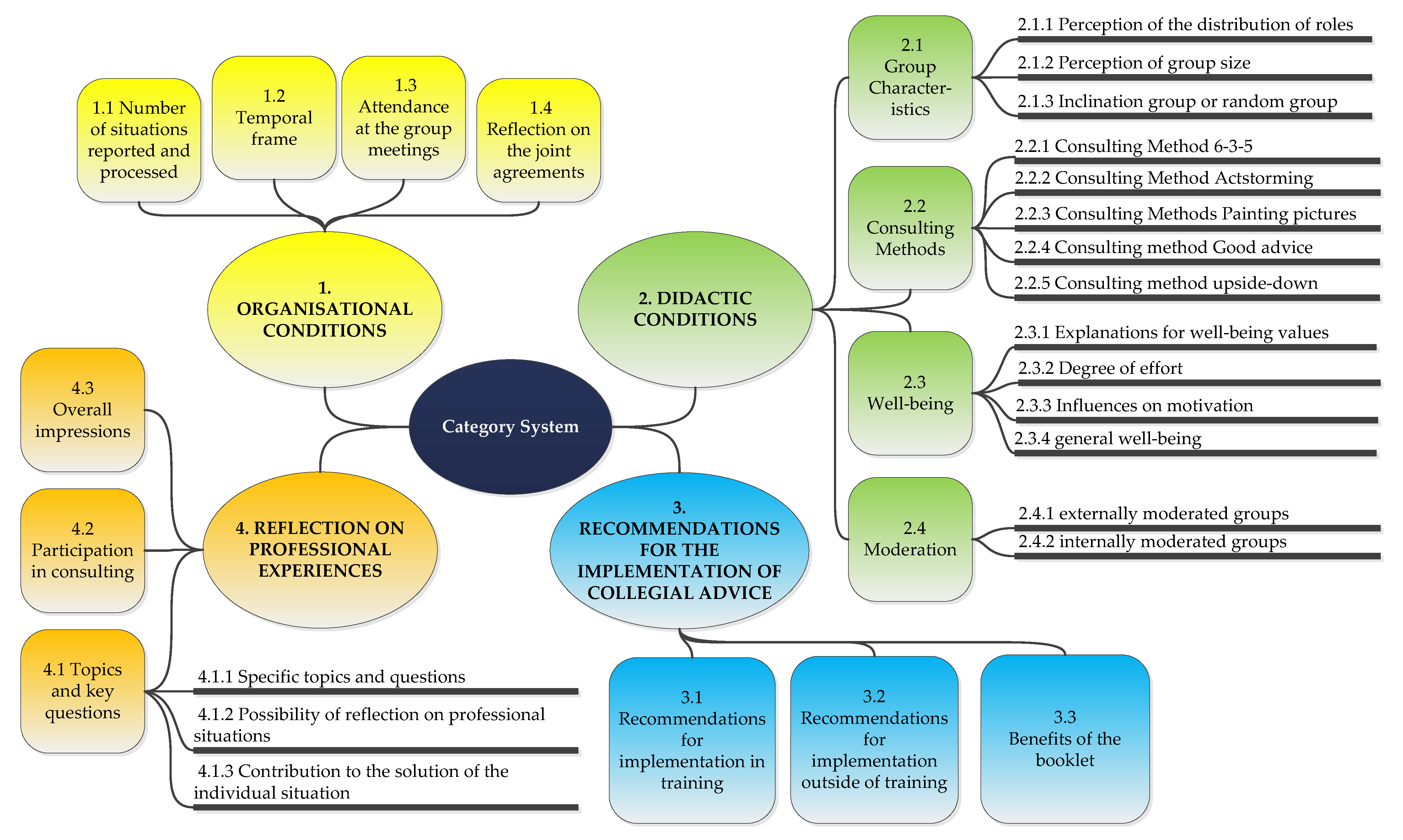

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Guideline for the Focus Group Interview

- Content

- Phase one

- Phase two

- Phase three

- Opening introductory question.

- Didactic and organizational conditions

- Number of situations told and processed:

- Role distribution:

- Attendance:

- Method usage:

- Duration of meetings:

- Suitability for reflection on professional experiences and motivation

- to use theoretical knowledge at the learning site-topics and key questions:

- Questions about possible influencing factors:

- Joint agreements on collegial consultation:

- Framework:

- Description of the evaluation of collegial consultation from the point

- of view of the participants:

- Closing Question:

- Phase four

- Phase one

- Includes the welcome, presentation of the method, and an opening question to kick off the discussion.

- “Welcome, nice to have you all here.

- I would like to do a focus group interview with you now. This is an interview that we will conduct here in the group. I will be recording this so that I can later document the content of the interview. I would like to explain what we will be doing for the next 90 minutes. I have prepared some questions that I would like to ask you. Furthermore, I have evaluated the satisfaction forms and protocols and from these I have compiled some figures for this group here. I will ask you to interpret and analyze these numbers. The interpretation specifically asks for your personal, own perception of things. The analysis is primarily to find explanations for certain things and, if necessary, to present correlations, also from the group’s point of view. In summary, the goal of the interview is that they can express their experiences from the collegial consultation and learn how the others experienced the consultations. Four things are particularly important to me:

- First, this is not a test or an exam. It is about the honest expression of personal feelings. So it is not possible to say anything wrong.

- Second, I am interested in capturing the meanings that you as a group or individual associate with collegial consultation. In doing so, we may be able to find explanations for certain data together and show connections. Again, this is not about “right” or “wrong.”

- Third, it is important that all are allowed and encouraged to participate. Every statement helps me to clarify my research questions and to arrive at results. This also means that you are always allowed to speak. You are allowed to express your experiences and can bring in examples. You are allowed to refer to what others have said or have a conversation among yourselves. Repetitions are not a problem. You could also say that you are responsible for the content, and I am responsible for the structure. In order for the recording to be successful, please do not speak in a jumbled manner, but one after the other.

- The fourth point I would like to make is that I do not want to evaluate your group in any way, either with the numbers I am about to show you or with the content of the interviews. The interviews are also not published as a whole but are used to test my hypotheses. It went the way it went, and that is very good. The interviews will not change that. So you do not have to defend yourself or anything like that. I am just asking for your perspective on things. Finally, I would like to say that the interview refers to the entire period of collegial consultation. So to all seven dates from February 2018 to November 2018.

- All right, everybody in agreement? Or is there anything else you would like to know beforehand? In order to be able to classify your voices a bit better afterwards, I would like to ask you for the following: please say the sentence “I am participant number one, two ...” one after the other.”

- Phase two

- Is started by an introductory or transition question, which specifically introduces the topic. The script is distributed

- “I would like to talk to you about the number of situations, role distribution, attendance, use of methods, duration of meetings, topics and key questions, WHO-5 satisfaction questionnaire results, joint agreements, and general impressions. You will find this on the first page of the script (note: these are the respective collections of numbers about the groups).

- Are you ready for the interview?”

- Phase three

- Forms the centre of the discussion, i.e., the actual questions related to the research interest are addressed here.

- Opening introductory question.

- “You have now completed a total of 30 hours of training and seven counselling appointments. Please describe what impressions this has left on you. Or put another way, what would you tell a good friend about what it was like?”

- Didactic and organizational conditions

- Before each question, the corresponding diagram is briefly explained in its structure (not the content)

- Number of situations told and processed:

- Here you can see the diagram on the situations told and worked on. Your group has reported a total of x situations and advised z situations. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your perspective.

- Supplemental questions:

- Did you find the amount appropriate?

- Did you sometimes find it difficult to name professional situations? Why?

- Role distribution:

- You can see the diagram of role distribution here. You have distributed the roles in each meeting as follows. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your perspective.

- Supplemental questions:

- Did you feel comfortable with the distribution of roles?

- I noticed that some people did not bring a case. Do you have an explanation for this?

- How did you feel about the roles?

- Did you feel comfortable with the separation of roles?

- Is the group size and composition appropriate?

- Attendance:

- Here you can see the attendances and absences. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your perspective.

- Method usage:

- You can see the method usage chart here. You have used the methods with the following frequency. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your perspective.

- Supplementary questions:

- Were there any favorite methods or methods that you completely disliked?

- Duration of meetings:

- You can see here the graph of the average duration of the meetings. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your point of view.

- Suitability for reflection on professional experiences and motivation to use theoretical knowledge at the learning site - topics and key questions:

- Here you can see a list of the overarching themes and key questions. Take a look at it at your leisure. Afterwards, I would love to hear your impressions on them.

- Supplemental Questions:

- What do you see as the main themes? Can you form categories or identify similarities?

- Does this reflect the problems of your daily work?

- How helpful were the results of the consultations? Examples?

- Were you able to take something away from the consultation for your everyday work?

- Were the situations solved? If not, how did you feel about it?

- Is coll. counselling a good way to reflect on professional experiences? Always? Never?

- Questions about possible influencing factors:

- Here you can see the diagram of the well-being values of your group. These are derived from the WHO-5 sheets that you filled out at the beginning of the consultations. Starting in February 2018 and ending in November 2018. 100 would mean complete satisfaction, zero would mean complete dissatisfaction. These are the averages of your group and not an individual. Please look at the averages for your group. Please interpret and analyze the numbers from your perspective.

- Supplemental Questions:

- Can you explain the highs and lows? (Note: possibly bring in midterm and vacation, course instructor changes, outpatient assignments as possible factors).

- How would you describe your motivation to participate?

- Were there things that helped or hindered your motivation to participate?

- Were there any other influences that helped or hindered your consultation?

- Joint agreements on collegial consultation:

- You developed a code of conduct of sorts before you began the consultations. I have presented this to you in the following overview, which you also know from the method reader. Please take another look at it at your leisure. Could you please give me some more feedback on this as well?

- Supplementary questions:

- Which aspects were particularly effective, which less so?

- Which ones did you feel were particularly important? Do you have an example?

- Framework:

- Groups 1 and 2:

- I accompanied the group as an external facilitator. In your view, was this necessary or rather a hindrance? Why?

- Groups 3 and 4:

- This group only had an external facilitator at the first meeting, after that you worked completely independently. Would you have liked an external facilitator or was it good the way it was? Why?

- Description of the evaluation of collegial consultation from the point of view of the participants:

- From your point of view, does it make sense to include collegial consultations in the training?

- Why? Why not? Examples?

- Closing Question:

- Finally, I ask each of you to share one final sentence that expresses your impressions of the consultations.

- Phase four

- Is designed in the sense of a detachment. The facilitator explains the further procedure, thanks, and says goodbye to the participants.

- “Is there anything else you would like to say? Thank you very much, that is it.

- When I have data from all four groups together, I will sit down and begin to analyze the data. I will not be able to finish that in the time it takes you to finish your exam, though. However, I would like to get back to you with an interim status before you are gone. Then you will have an overview of what has been going on until then. And if you leave me an email address, I’ll let them know the final results.”

- So thanks again and see you soon.”

- Status as of 09.01.2018.

References

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning; European Union: Brussel, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qalehsari, M.Q.; Khaghanizadeh, M.; Ebadi, A. Lifelong learning strategies in nursing: A systematic review. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5541–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindon, S.L. Professional Development Strategies to Enhance Nurses’ Knowledge and Maintain Safe Practice. AORN J. 2017, 106, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expert commission according to Section 53 Act on the nursing professions. Rahmenlehrpläne für den theoretischen und praktischen Unterricht. Available online: https://www.bibb.de/dienst/veroeffentlichungen/de/publication/download/16560 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Erpenbeck, J.; Rosenstiel, L.; Grote, S.; Sauter, W. Handbuch Kompetenzmessung; Schäffer-Poeschel: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Act on the Nursing Professions of 17 July 2017 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 2581). Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/P/PflBG_gueltig_am_1.1.2020_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Training and Examination Regulations for the Nursing Professions of 2 October 2018 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1572). Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/P/PflAPrV_gueltig_am_1.1.2020_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Rauner, F.; Evans, K.; McLennon, S.M. Measuring and Developing Professional Competences in COMET; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Price, S.L. Becoming a nurse: A meta-study of early professional socialization and career choice in nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herwig-Lempp, J. Resource-Oriented Teamwork: A Systemic Approach to Collegial Consultation; Vandenhoeck et Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papermaster, A.; Champion, J.D. What is curbside consultation for the nurse practitioner? J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 33, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, J. The organization of clinical supervision within the nursing profession: A review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 23, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, N. Clinical supervision in undergraduate nursing students: A review of the literature. E-J. Bus. Educ. Scholarsh. Teach. 2013, 7, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gajree, N. Can Balint groups fill a gap in medical curricula? Clin. Teach. 2021, 18, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, C. Becoming A Reflective Practitioner, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Korthagen, F.A.J. Reflective Teaching and Preservice Teacher Education in the Netherlands. J. Teach. Educ. 1985, 36, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, E.D. Intervision: Kollegiales Coaching professionell gestalten, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, K.-O. Wirkprozesse und personenbezogene Wirkungen von kollegialer Beratung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Staempfli, A.; Fairtlough, A. Intervision and Professional Development: An Exploration of a Peer-Group Reflection Method in Social Work Education. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 49, 1254–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcross, J.C.; Geller, J.D.; Kurzawa, E.K. Conducting psychotherapy with psychotherapists II: Clinical practices and collegial advice. J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 2001, 10, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roy, V.; Genest Dufault, S.; Châteauvert, J. Professional Co-Development Groups: Addressing the Teacher Training Needs of Social Work Teachers. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 2014, 34, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddewig, M. Kollegiale Beratung in der Gesundheits- und Krankenpflege: Auswirkungen auf das emotionale Befinden von Auszubildenden; Mabuse: Frankfurt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, E.; MacQueen, K.M.; Neidig, J.L. Beyond the Qualitative Interview: Data Preparation and Transcription. Field Methods 2003, 15, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 4th ed.; Beltz Juventa: Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Villiger, J.; Schweiger, S.A.; Baldauf, A. Making the Invisible Visible: Guidelines for the Coding Process in Meta-Analyses. Organ. Res. Methods 2021, 25, 716–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.L.; Prediger, D.J. Coefficient Kappa: Some Uses, Misuses, and Alternatives. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1981, 41, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An Application of Hierarchical Kappa-type Statistics in the Assessment of Majority Agreement among Multiple Observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosbrugger, H.; Kelava, A. Qualitätsanforderungen an Tests und Fragebogen („Gütekriterien“). In Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion; Moosbrugger, H., Kelava, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R. Berufliche Identität als Dimension beruflicher Kompetenz: Entwicklungsverlauf und Einflussfaktoren in der Gesundheits- und Krankenpflege; W. Bertelsmann Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grässlin, H.-M.; Fallner, H. Kollegiale Beratung: Eine Systematik zur Reflexion des beruflichen Alltags, 2nd ed.; Busch: Hille, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, K.-O. Kollegiale Beratung: Problemlösungen Gemeinsam Entwickeln, 2nd ed.; Rowohlt: Reinbek, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen, J.; Huizing, J. Methoden für die Intervision: Ein Fächer mit 20 effektiven Tools; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Category | Type of Category | Anchor Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. ORGANISATIONAL CONDITIONS | Superordinate category | Always empty |

| 1.1 Number of situations reported and processed | main category | “We talked so much about our problems that we first briefly told all the situations and then at the end we managed only one consultation.” [Participant 21] |

| 1.2 Temporal frame | main category | “The time was reasonable, and we usually managed two situations well. If one of them took a little longer, that was also fine.” [Participant 21] |

| 1.3 Attendance at the group meetings | main category | “It is noticeable that one person was not there so often, only four times.” [Participant 17] |

| 1.4 Reflection on the joint agreements | main category | “I place a lot of value on respectful interaction. No matter what someone says, you shouldn’t laugh about it or make fun of it. That what is said is respected and accepted, that is very important to me.” [Participant 19] |

| 2. DIDACTIC CONDITIONS | superordinate category | Always empty |

| 2.1 Group characteristics | main category | Empty |

| 2.1.1 Perception of the distribution of roles | subcategory | “I felt comfortable in both roles because I thought: I’ll use this for myself. And when I have a problem and others give me something, I like to take that with me. I also like to give advice.” [Participant 21] |

| 2.1.2 Perception of group size | subcategory | “I found it easy to talk about things because we were such a small group. In larger groups, some things are more difficult to discuss. I wouldn’t dare tell anything there.” [Participant 17] |

| 2.1.3 Inclination group or random group | subcategory | “I think it’s an advantage when a group is drawn. You hear opinions from people you wouldn’t otherwise ask.” [Participant 21] |

| 2.2 Consulting methods | main category | empty |

| 2.2.1 Consulting method 6-3-5 | subcategory | “I think the ‘6-3-5 method’ is the best way to get your advice across. The way you really mean it.” [Participant 23] |

| 2.2.2 Consulting method Actstorming | subcategory | “’Actstorming’ did not go over well with our group.” [Participant 21] |

| 2.2.3 Consulting methods Painting pictures | subcategory | “The other methods were easier to get advice across.” [Participant 23] |

| 2.2.4 Consulting method Good advice | subcategory | “I think the ‘good advice’ method is the best way to get your advice across. The way you really mean it.” [Participant 23] |

| 2.2.5 Consulting method Upside-down | subcategory | “I think ‘upside-down’ is a method that helps when you get stuck. If you have no ideas, you can definitely say what you should not do. This leads to possibilities of what you could do. Whether this is always useful, I do not know.” [Participant 21] |

| 2.3 Well-being | main category | empty |

| 2.3.1 Explanations for well-being values | subcategory | “After the vacation or after an interval of free time, I was fine. And then I noticed that my well-being questionnaires turned out much better than before.” [Participant 22] |

| 2.3.2 Degree of effort | subcategory | “I found it was hard to remember an example and present it as a case or problem when it had been in the past for a while.” [Participant 22] |

| 2.3.3 Influences on motivation | subcategory | “When we did the consultation in the morning, it was better. In the afternoon, I was pretty knocked out. I didn’t feel like discussing things anymore.” [Participant 17] |

| 2.3.4 General well-being | subcategory | “Overall, I think the values are very poor.” [Participant 17] |

| 2.4 Moderation | main category | Empty |

| 2.4.1 Externally moderated groups | subcategory | “I find externally moderated is better.” [Participant 22] |

| 2.4.2 Internally moderated groups | subcategory | Empty |

| 3. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COLLEGIAL ADVICE | superordinate category | Always empty |

| 3.1 Recommendations for implementation in training | main category | “The consultations were helpful for me. I would have liked the collegial advice sooner, in the first year of teaching, before it all starts.” [Participant 18] |

| 3.2 Recommendations for implementation outside of training | main category | “I would like to see collegial consultation continued after the training.” [Participant 22] |

| 3.3 Benefits of the booklet | main category | “I found the booklet very helpful, especially in the beginning. I didn’t remember many of the methods. I got the methods mixed up. In the end, I didn’t need the booklet anymore.” [Participant 19] |

| 4. REFLECTION ON PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCES | superordinate category | Always empty |

| 4.1 Topics and key questions | main category | “Sometimes I have problems that I think are petty and that I don’t need to discuss.” [Participant 22] |

| 4.1.1 Specific topics and questions | subcategory | „Often, these are topics that have to do with the team. Whether it’s your Mentor, colleagues, or ward manager.” [Participant 22] |

| 4.1.2 Possibility of reflection on professional situations | subcategory | “There were examples where you were no longer in the situation. But I still found the results of the consultation helpful. For example, if you get into a similar situation.” [Participant 21] |

| 4.1.3 Contribution to the solution of the individual situation | subcategory | “We solved problems through different methods, and I found these methods good and varied.” [Participant 20] |

| 4.2 Participation in consulting | main category | “I think it’s a shame that not everyone in the group contributed so much. I would have liked to hear more from some.” [Participant 21] |

| 4.3 Overall impressions | main category | “I liked the collegial advice very much.” [Participant 17] |

| Number and path 4.1.2 Reflection on professional experiences\Topics and key questions\Possibility of reflection on professional situations |

| Name of the category Possibility of reflection on professional situations |

| Description of the category This category summarizes content that indicates whether collegial advice is generally suitable for reflecting on professional experiences. Concrete examples are coded as well as general statements about the possibility of reflecting on professional experiences. Content on the degree of assistance provided by collegial consultation is also included in the coding. This is explicitly about the perception of whether collegial advice seems fundamentally suitable or unsuitable. The objective is to find out whether the participants accept or reject collegial advice as a solution approach for dealing with professional situations. |

| Application of the category This category is used when references are made to the possibility of reflecting on the professional situation. |

| Example of application „There were examples where you were no longer in the situation. But I still found the results of the consultation helpful. For example, if you get into a similar situation.” [Participant 21] |

| Differentiation from other categories (optional) empty |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wellensiek, S.; Ehlers, J.P.; Zupanic, M. Designing Categories for a Mixed-Method Research on Competence Development and Professional Identity through Collegial Advice in Nursing Education in Germany. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2517. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122517

Wellensiek S, Ehlers JP, Zupanic M. Designing Categories for a Mixed-Method Research on Competence Development and Professional Identity through Collegial Advice in Nursing Education in Germany. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2517. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122517

Chicago/Turabian StyleWellensiek, Stefan, Jan P. Ehlers, and Michaela Zupanic. 2022. "Designing Categories for a Mixed-Method Research on Competence Development and Professional Identity through Collegial Advice in Nursing Education in Germany" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2517. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122517

APA StyleWellensiek, S., Ehlers, J. P., & Zupanic, M. (2022). Designing Categories for a Mixed-Method Research on Competence Development and Professional Identity through Collegial Advice in Nursing Education in Germany. Healthcare, 10(12), 2517. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122517