Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

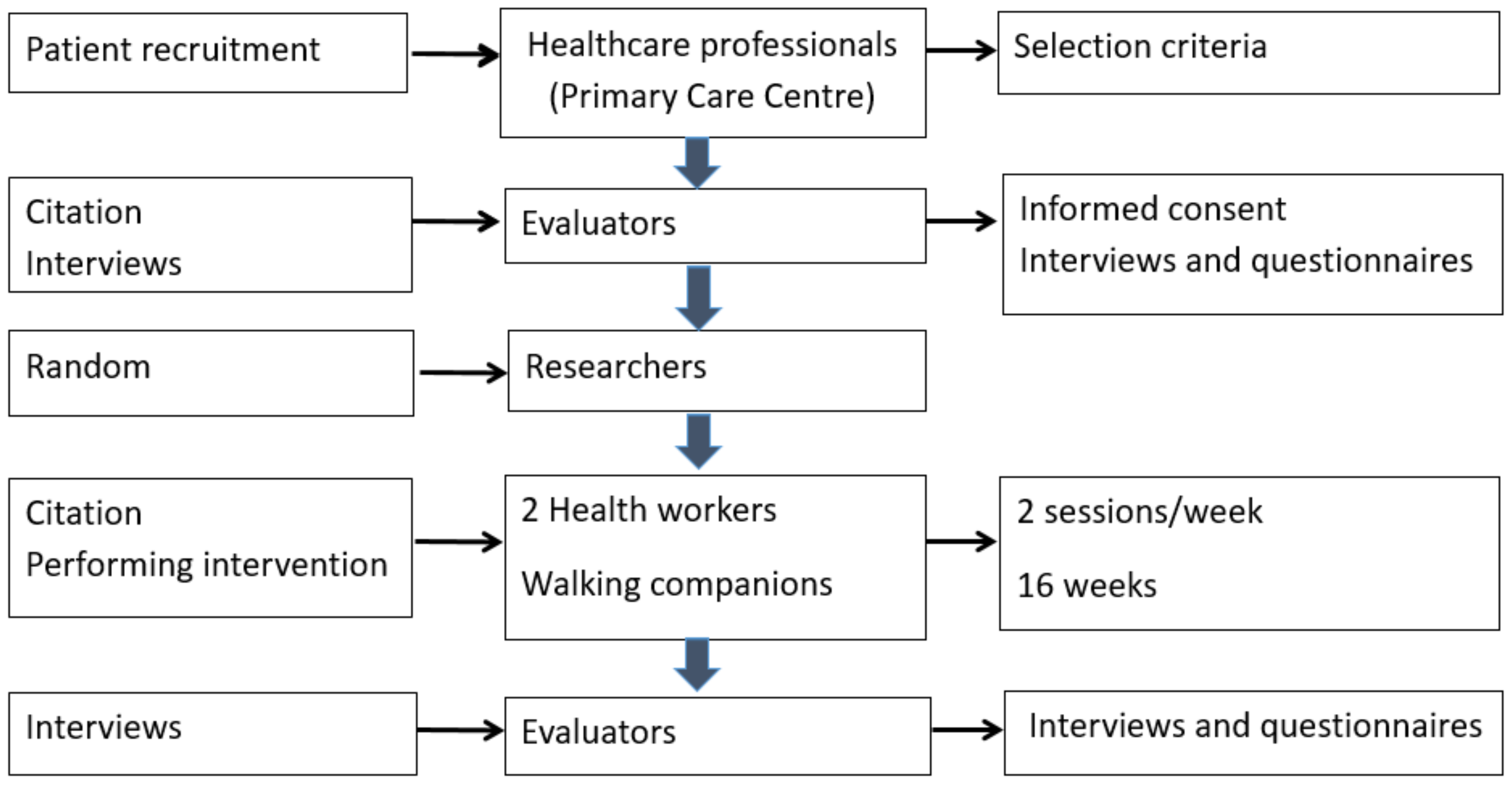

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention

2.2. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

2.3. Variables and Measurement Methods

- 1.

- Sociodemographic variables: sex, age, marital status (single, married, separated, widowed), living alone (yes/no), educational level (no education/primary education/secondary education/higher education). Basic health area: semi-urban (<15,000 inhabitants) or urban (≥15,000 inhabitants).

- 2.

- Engage in regular physical activity (yes, no).

- 3.

- Clinical remission of depression or response to intervention upon completion of the intervention. Clinical remission was defined as a Beck Inventory (BDI-II) score <14 points, and a response to the intervention was defined as a decrease from the baseline score [25].

- 4.

- Remission of clinical anxiety or response to the intervention after the intervention is completed. Clinical remission was defined as a score <10 points on the GAD-7 scale (Generalised Anxiety Disorder), and a response to the intervention was defined as a reduction in the score from baseline [26].

- 5.

- Improvements in social support once the intervention is over. A decrease in the DUKE-UNC-11 Social Support Questionnaire score from baseline, and good social support; a score of <32 points was considered an improvement in social support [27].

- 6.

- 7.

- Improved perception of health status after the intervention. An improvement in the perception of health status was considered an increase in the score on the scale.

- 8.

- Outcome variables measuring viability in the intervention group:

- -

- Satisfaction with the intervention: At the end of the intervention, a satisfaction survey was conducted, with 5 items and a 5-point Likert scale.

- -

- Adherence to the intervention: Attendance at walks was recorded. Adherence was calculated for the intervention variable (attendance at 75% or more of the sessions).

- -

- Number of visits made to the primary care centre: pre-intervention (4 months), from 2 November 2018 to 1 March 2019; intervention (4 months), 2 March 2019 to 1 July 2019; post-intervention (4 months), 2 July to 1 November 2019.

- 9.

- Any variables that can act as confounders or effect modifiers:

- -

- Pharmacological treatment. The DDD (defined daily dose, WHO) was calculated for each active ingredient, taking into account the number of days, the dose dispensed, and the route of administration of the drug. The active ingredients registered were those belonging to the antidepressant and anxiolytic groups.

2.4. Participant Timeline

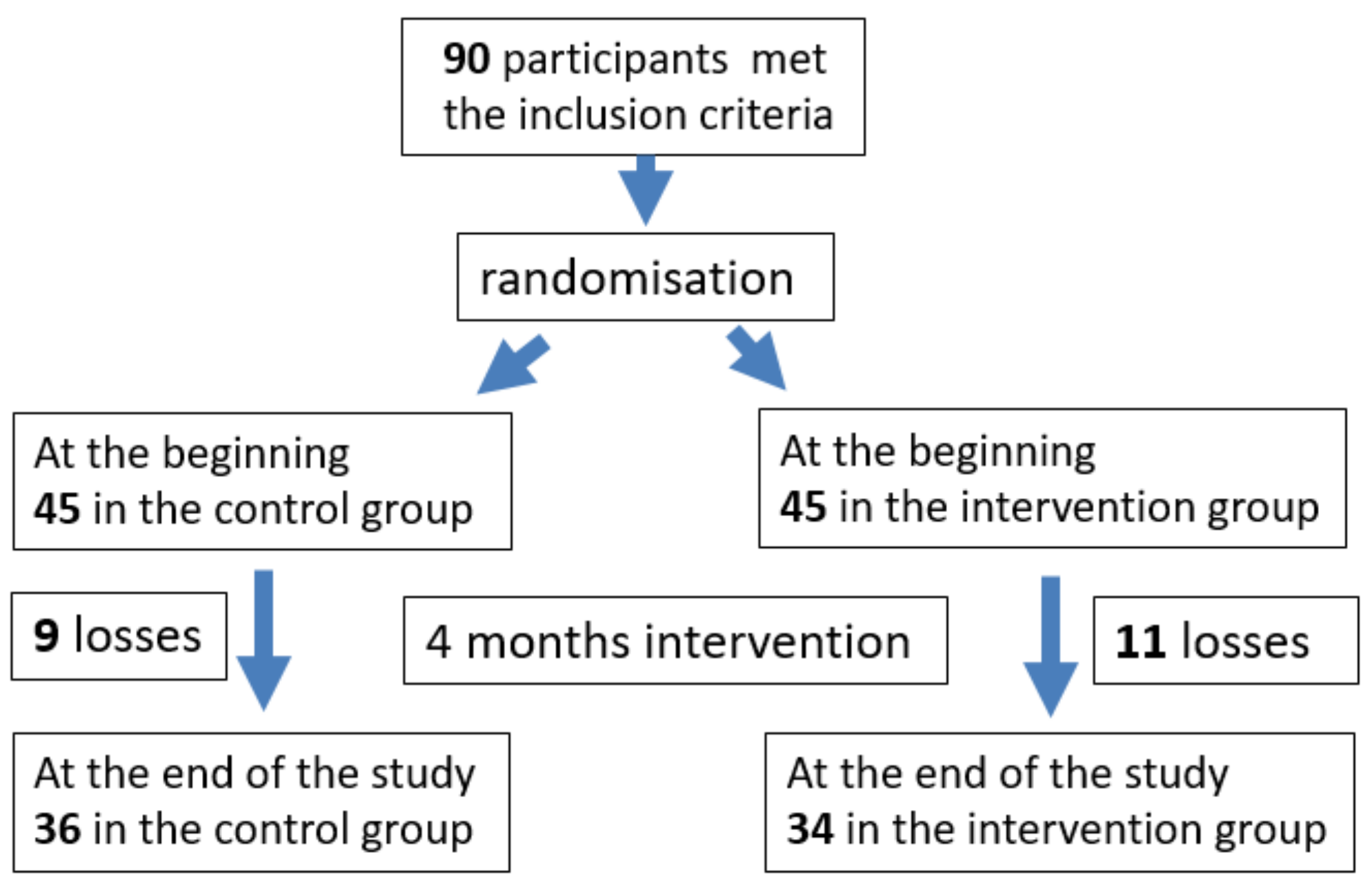

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

2.6. Recruitment

2.7. Assignment of Interventions (for Controlled Trials)

2.8. Data Analysis

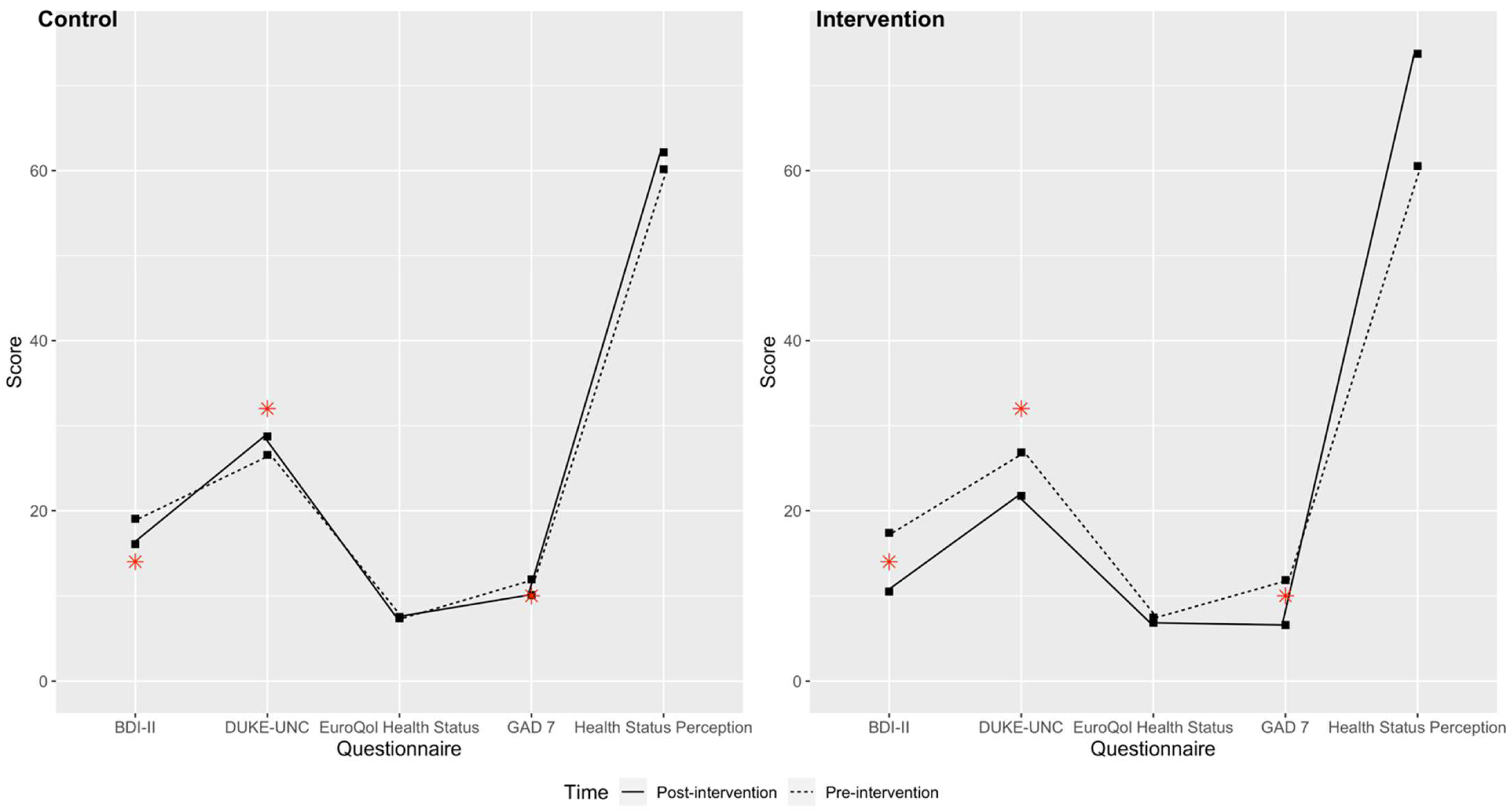

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Población de España Mayor de 65 años en el 2020. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/630678/poblacion-de-espana-mayor-de-65-anos/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Proyecciones de Población Mayor de 65 en España. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/pp_2018_2068.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Urzúa, A. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: Elementos conceptuales. Rev. Med. Chile 2010, 138, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Vivas-Consuelo, D.; Alvis-Guzman, N. Is Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) a valid indicator for health systems evaluation? Springerplus 2013, 2, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubetkin, E.I.; Jia, H.; Franks, P.; Gold, M.R. Relationship among Sociodemographic Factors, Clinical Conditions, and Health-related Quality of Life: Examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. General Population. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 2187–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Comice, P.; Belchín, A.; Erdozain, M.Á.; Cáliz, L.; Torres, S.; Rodríguez, R. Profiles of loneliness and social isolation in urban population. Aten. Primaria 2020, 52, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanet, B.; van Tilburg, T.G. Loneliness declines across birth cohorts: The impact of mastery and self-efficacy. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyqvist, F.; Nygård, M.; Scharf, T. Loneliness amongst older people in Europe: A comparative study of welfare regimes. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 16, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, E.; Fleming, J.; Dening, T.; Khaw, K.T.; Brayne, C. Is loneliness associated with increased health and social care utilisation in the oldest old? Findings from a population-based longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evid. Based Nurs. 2014, 17, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcentaje de Personas Mayores Diagnosticadas con Depresión en España en 2017, por grupos de edad. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/638507/porcentaje-de-personas-mayores-con-depresion-por-edad-en-espana/ (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Delle Fave, A.; Bassi, M.; Boccaletti, E.S.; Roncaglione, C.; Bernardelli, G.; Mari, D. Promoting Well-Being in Old Age: The Psychological Benefits of Two Training Programs of Adapted Physical Activity. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolhaas, C.M.; Dhana, K.; van Rooij, F.J.A.; Schoufour, J.D.; Hofman, A.; Franco, O. Physical activity types and health-related quality of life among middle-aged and elderly adults: The Rotterdam Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallar-Castillón, P.; Peralta, P.S.O.; Banegas, J.R.; López, E.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Actividad física y calidad de vida de la población adulta mayor en España. Med. Clín. 2004, 123, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampinen, P.; Heikkinen, R.-L.; Kauppinen, M.; Heikkinen, E. Activity as a predictor of mental well-being among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, P.-W.; Steptoe, A.; Liao, Y.; Sun, W.-J.; Chen, L.-J. Prospective relationship between objectively measured light physical activity and depressive symptoms in later life. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J.E.; Lawlor, B.A. Exercise and social support are associated with psychological distress outcomes in a population of community-dwelling older adults. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarró-Maluquer, M.; Ferrer-Feliu, A.; Rando-Matos, Y.; Formiga, F.; Rojas-Farreras, S.; Grupo de Estudio Octabaix Depresión en ancianos. Prevalencia y factores Asociados [Depression in the elderly: Prevalence and associated factors]. SEMERGEN-Med. Fam. 2013, 39, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Jones, A. Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochcovitch, M.D.; Deslandes, A.C.; Freire, R.C.; Garcia, R.F.; Nardi, A.E. The effects of regular physical activity on anxiety symptoms in healthy older adults: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guszkowska, M. Effects of exercise on anxiety, depression and mood. Psychiatr. Polska 2004, 38, 611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, L.; Kremers, S.; Walsh, A.; Brug, H. How is your walking group running? Health Educ. 2006, 106, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K. Walking together: The embodied and mobile production of a therapeutic landscape. Health Place 2013, 24, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D.R.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2011, 43, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J.; Perdogón, A.L.; Vázquez, C. Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 2. Propiedades psicométricas en población general. [Spanish adaptation of the Beck-II Depression Inventory (BDI-II): 2. Psychometric Properties in the General]. Clínica Salud 2003, 14, 249–280. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saameño, J.A.B.; Sánchez, A.D.; del Castillo, J.D.D.L.; Claret, P.L. Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social funcional Duke-UNC-11 [Validity and reliability of the Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Questionnaire]. Atención Primaria: Publicación Of. Soc. Española Fam. Comunitaria 1996, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy 1996, 37, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, X.; Roset, M.; Montserrat, S.; Herdman, M.; Segura, A. La versión española del EuroQol: Descripción y aplicaciones [The Spanish version of EuroQol: A description and its applications. Med. Clin. 1999, 112 (Suppl. S1), 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2010; pp. 1–758. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–427. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–983. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Nonnormal Variables: Problems and Remedies; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Newbery Park, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R.; Robertson, A.; Jepson, R.; Maxwell, M. Walking for depression or depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Keogh, J.W.; Kolt, G.S.; Schofield, G.M. The long-term effects of a primary care physical activity intervention on mental health in low-active, community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Berens, Å.; Fielding, R.A.; Gustafsson, T.; Kirn, D.; Laussen, J.; Nydahl, M.; Reid, K.; Travison, T.G.; Zhu, H.; Cederholm, T.; et al. Effect of exercise and nutritional supplementation on health-related quality of life and mood in older adults: The VIVE2 randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancini, R.L.; Rayes, A.B.R.; de Lira, C.; Sarro, K.J.; Andrade, M.S. Pilates and aerobic training improve levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in overweight and obese individuals. Arq. Neuro Psiquiatria 2017, 75, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.D.S.S.C.B.; Souza, E.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.S.; Fett, C.A.; Piva, A.B. The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay Smith, G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; Van Uffelen, J.G. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azpiazu Garrido, M.; Cruz Jentoft, A.; Villagrasa Ferrer, J.R.; Abanades Herranz, J.C.; García Marín, N.; Alvear Valero de Bernabé, F. Factores asociados a mal estado de salud percibido o a mala calidad de vida en personas mayores de 65 años. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2002, 76, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Di Onofrio, V.; Spica, V.R.; Mastronuzzi, R.; Krauss, P.R.; Belfiore, P.; Buono, P.; Liguori, G. Improving physical fitness and health status perception in community-dwelling older adults through a structured program for physical activity promotion in the city of Naples, Italy: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 45) | Intervention (n = 45) | ||

| Sex (% female) | 81.81% | 71.43% | 0.376 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 74 (5.18) | 75 (6.02) | 0.632 |

| Coexistence core | 0.865 | ||

| Lives with own family | 28 (62.22) | 28 (62.22) | |

| Lives with family of origin | 1 (2.22) | 2 (4.44) | |

| Lives alone | 16 (35.56) | 14 (31.11) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | 1 (2.22) | |

| Primary care team | 0.833 | ||

| Manresa (urban) | 14 (31.11) | 15 (33.33) | |

| Sant Joan de Vilatorrada (semi-urban) | 15 (33.33) | 16 (35.56) | |

| Súria (semi-urban) | 16 (35.36) | 13 (28.89) | |

| Educational level | 0.905 | ||

| No education | 6 (13.33) | 4 (8.89) | |

| Incomplete compulsory education | 20 (44.44) | 21 (46.67) | |

| Complete compulsory education | 13 (28.89) | 15 (33.33) | |

| High school or vocational training | 5 (11.11) | 3 (6.67) | |

| Completed university studies | 1 (2.22) | 1 (2.22) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | 1 (2.22) | |

| Marital status | 0.322 | ||

| Single | 4 (8.89) | 5 (11.11) | |

| Married or living with a partner | 23 (51.11) | 21 (46.67) | |

| Separated or divorced | 3 (6.67) | 4 (8.89) | |

| Widowed | 15 (33.33) | 11 (24.44) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | 4 (8.89) | |

| Engages in regular physical activity | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 17 (37.78) | 17 (37.78) | |

| No | 26 (57.78) | 27 (60.00) | |

| Others | 2 (4.44) | 1 (2.22) | |

| Questionnaire results | |||

| Health status—EuroQol (mean and SD) a | 7.38 (1.62) | 7.47 (1.70) | 0.798 |

| Health status perception (mean and SD) a | 60.15 (18.11) | 60.53 (21.18) | 0.927 |

| Social support—DUKE-UNC (mean and SD) a | 26.55 (11.05) | 26.84 (12.29) | 0.907 |

| Social support—DUKE-UNC | 0.823 | ||

| Yes (<32) | 31 (68.89) | 29 (64.44) | |

| No (≥32) | 14 (31.11) | 16 (35.56) | |

| Generalised anxiety—GAD-7 (mean and SD) a | 11.93 (4.84) | 11.84 (4.98) | 0.931 |

| Generalised anxiety—GAD-7 | 1 | ||

| Yes (<10) | 14 (31.11) | 15 (33.33) | |

| No (≥10) | 31 (68.89) | 30 (66.67) | |

| Depression—BDI-II (mean and SD) a | 19.04 (7.21) | 17.38 (7.44) | 0.285 |

| Depression—BDI-II | 0.763 | ||

| Yes (<14) | 12 (26.67) | 14 (31.82) | |

| No (≥14) | 33 (73.33) | 30 (68.18) | |

| Control (n = 36) | Intervention (n = 34) | Change Control vs. Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value 4 m | Change | 95% CI of Change | p-Value * | Value 4 m | Change | 95% CI of Change | p-Value * | p-Value | |

| EuroQol Health status | 7.53 (1.56) | 0.08 (1.23) | (−0.33; 0.49) | 0.686 | 6.85 (1.54) | −0.38 (1.54) | (−0.92; 0.15) | 0.156 | 0.168 |

| Health status perception | 62.14 (14.98) | 1.83 (16.92) | (−0.39; 7.56) | 0.520 | 73.73 (18.51) | 11.76 (18.64) | (5.26; 18.27) | <0.001 | 0.023 |

| DUKE-UNC | 28.72 (11.93) | 2.97 (9.81) | (−0.35; 6.29) | 0.078 | 21.73 (10.38) | −3.59 (11.68) | (−7.66; 0.49) | 0.082 | 0.013 |

| GAD-7 | 10.08 (4.69) | −1.83 (4.48) | (−3.35; −032) | 0.019 | 6.59 (4.21) | −5.11 (5.73) | (−7.12; −3.12) | <0.001 | 0.009 |

| BDI-II | 16.05 (8.21) | −2.86 (5.64) | (−4.77; −0.95) | 0.004 | 10.50 (6.40) | −6.36 (8.27) | (−9.29; −3.43) | <0.001 | 0.046 |

| Depression (BDI-II) | ≥14 | <14 | RR Crude | RR Baseline Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | - | - |

| 8 (23.5) | 26 (76.5) | 1.62 (1.09; 2.39) | 1.59 (1.08; 2.33) |

| Anxiety disorder (GAD-7) | ≥10 | <10 | RR | RR |

| 18 (50.0) | 18 (50.0) | - | - |

| 8 (23.5) | 26 (76.5) | 1.53 (1.05; 2.23) | 1.45 (1.02; 2.07) |

| Social support | ≥32 | <32 | RR | RR |

| 16 (44.4) | 20 (55.5) | - | - |

| 8 (23.5) | 26 (76.5) | 1.37 (0.97; 1.95) | 1.36 (0.99; 1.88) |

| Group | Period Pre-Intervention 1 November 2018 to 28 February 2019 N = 45 Both Groups | Intervention Period 1 March 2019 to 30 June 2019 N Control = 36, n Intervention = 34 | Period Post-Intervention 1 July 2019 to 31 October 2019 N Control = 36, n Intervention = 34 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | Mean (SD) | Total Count | Mean (SD) | Total Count | Mean (SD) | |

| Intervention | 258 | 7.59 (5.78) | 223 | 6.76 (5.74) | 224 | 7.23 (8.15) |

| Control | 205 | 5.86 (3.67) | 248 | 7.09 (5.01) | 213 | 6.26 (4.34) |

| Comparison * | 0.137 | 0.798 | 0.533 | |||

| Control (n = 36) | Intervention (n = 34) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Change | More Medication | Less Medication | No Change | More Medication | Less Medication |

| 25 (69.44) | 8 (22.22) | 3 (8.33) | 28 (82.35) | 3 (8.82) | 3 (8.82) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Comellas, A.; Valmaña, G.S.; Catalina, Q.M.; Baena, I.G.; Mendioroz Peña, J.; Roura Poch, P.; Sabata Carrera, A.; Cornet Pujol, I.; Casaldàliga Solà, À.; Fusté Gamisans, M.; et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112203

Ruiz-Comellas A, Valmaña GS, Catalina QM, Baena IG, Mendioroz Peña J, Roura Poch P, Sabata Carrera A, Cornet Pujol I, Casaldàliga Solà À, Fusté Gamisans M, et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial. Healthcare. 2022; 10(11):2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112203

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Comellas, Anna, Glòria Sauch Valmaña, Queralt Miró Catalina, Isabel Gómez Baena, Jacobo Mendioroz Peña, Pere Roura Poch, Anna Sabata Carrera, Irene Cornet Pujol, Àngels Casaldàliga Solà, Montserrat Fusté Gamisans, and et al. 2022. "Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial" Healthcare 10, no. 11: 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112203

APA StyleRuiz-Comellas, A., Valmaña, G. S., Catalina, Q. M., Baena, I. G., Mendioroz Peña, J., Roura Poch, P., Sabata Carrera, A., Cornet Pujol, I., Casaldàliga Solà, À., Fusté Gamisans, M., Saldaña Vila, C., Vázquez Abanades, L., & Vidal-Alaball, J. (2022). Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial. Healthcare, 10(11), 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112203