Empirical Convergence Theory of Harmony Search Algorithm for Box-Constrained Discrete Optimization of Convex Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Harmony Search Algorithm

2.1. Basic Structure of Harmony Search

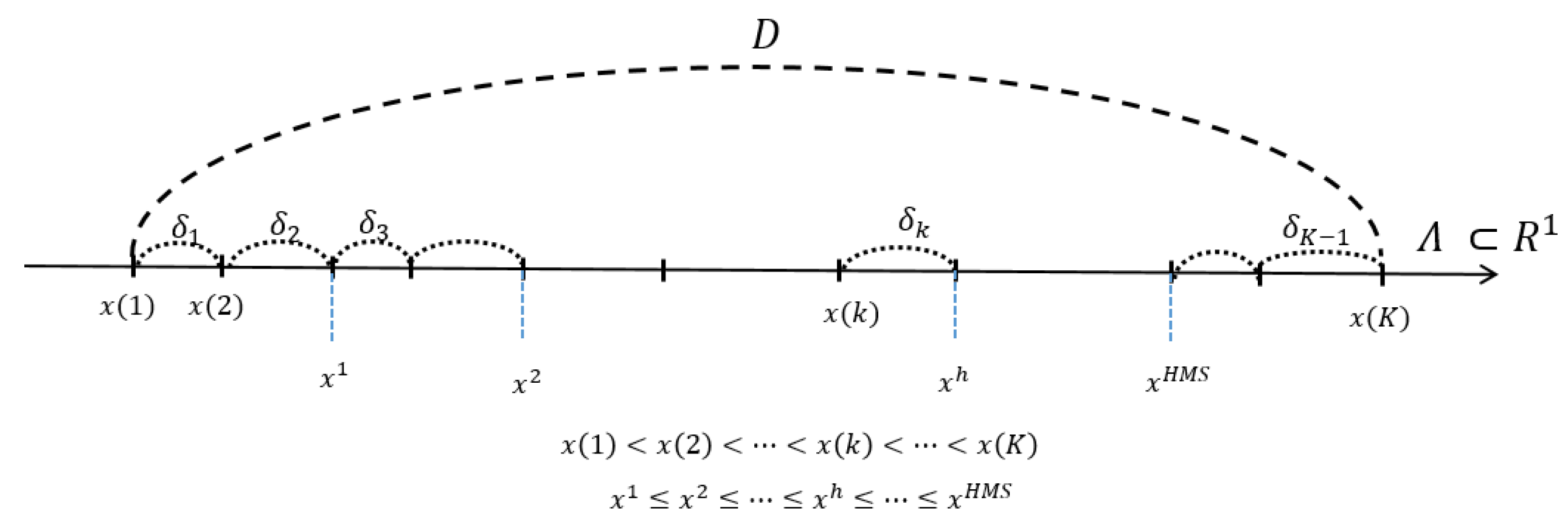

2.2. Solution Formula for Harmony Search without Pitch Adjustment

2.3. Solution Formula for Harmony Search with Pitch Adjustment

3. Empirical Convergence of Harmony Search

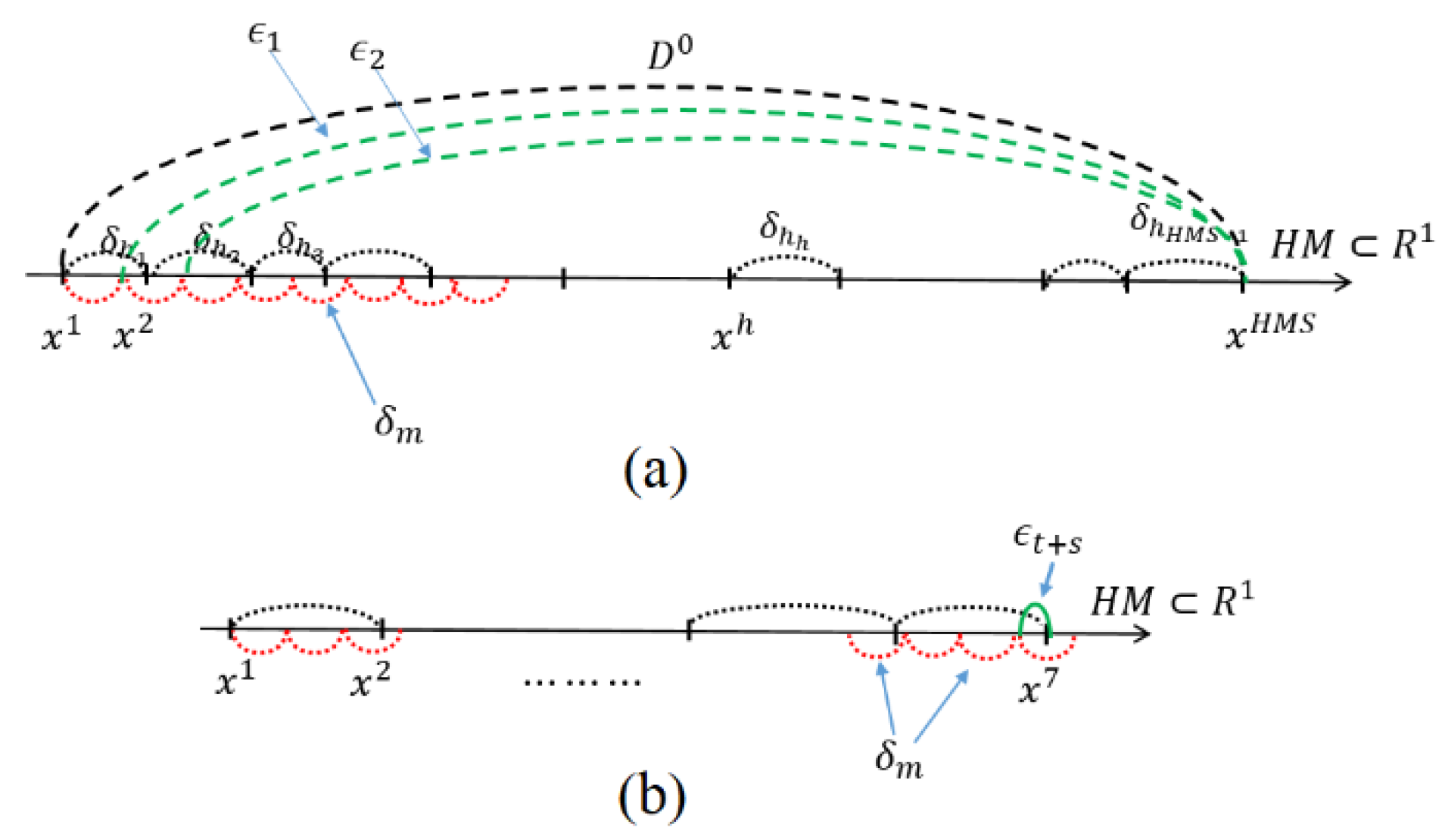

3.1. One Variable Case

- (a)

- & (c): Because the left-end smallest-value point will be replaced by some value except in the case of Here, note that . The smallest-value element can be newly updated by or . Consider that we are at the generation. Then, the previous is denoted as , and the newly updated smallest one from HM will be denoted as . Here,It is clear that

- (b)

- & (d): Because the right end point will be replaced by some value except in the case of , which shows better performance than . Here, note that . The largest-value element can be updated by or . Consider that we are at the generation. Then, the previous is denoted as , and the newly updated largest one from HM will be denoted as . Here,It is clear thatNow we prove the following theorem.

- (i)

- is a monotone decreasing sequence asis increased.

- (ii)

- Furthermore, the solutions in HM converge.

3.2. Multiple Variable Case

- (i)

- If then will be replaced by some which shows better performance than . Here, note that Therefore, which has the smallest norm, will be newly replaced by . Consider that we are at the generation, then the previous is denoted as . At that point, the newly updated smallest vector from HM will be denoted as . Here,

- (ii)

- If then will be replaced by another vector which shows better performance than . Here, note that . Therefore, which has the largest norm, will be newly replaced by . Consider that we are at the generation. Then the previous is denoted as . Then, the newly updated largest vector from HM will be denoted as . Here,

- (i)

- is a monotone decreasing sequence as is increased.

- (ii)

- Furthermore, the values in HM converge.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geem, Z.W.; Kim, J.H.; Loganathan, G.V. A new heuristic optimization algorithm: Harmony search. Simulation 2001, 76, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Geem, Z.W. A new metaheuristic algorithm for continuous engineering optimization: Harmony search theory and practice. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2004, 194, 3902–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W. Multiobjective Optimization of Time-Cost Trade-Off Using Harmony Search. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. ASCE 2010, 136, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W. Harmony Search Algorithms for Structural Design Optimization; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari-Heris, M.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Asadi, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Geem, Z.W. Harmony search algorithm for energy system applications: An updated review and analysis. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2019, 31, 723–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.Y.; Geem, Z.W.; Han, G.-T. Vanishing point detection for self-driving car using harmony search algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2018, 41, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W. Can Music Supplant Math in Environmental Planning? Leonardo 2015, 48, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-Y.; Ko, K.-E.; Geem, Z.W.; Sim, K.-B. Method that determining the Hyperparameter of CNN using HS Algorithm. J. Korean Inst. Intell. Syst. 2017, 27, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, S.H. A Modified Harmony Search Algorithm for Portfolio Optimization Problems. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2016, 50, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Daliri, S. Using Harmony Search Algorithm in Neural Networks to Improve Fraud Detection in Banking System. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 2020, 6503459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, P.-C.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Chou, C.-H. Using Dynamic Adjusting NGHS-ANN for Predicting the Recidivism Rate of Commuted Prisoners. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, G.; Hickmann, K.S.; Mniszewski, S.M.; Del Valle, S.Y.; Hyman, J.M. Optimizing human activity patterns using global sensitivity analysis. Comput. Math. Organ Theory 2014, 20, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Elyasigomari, V.; Lee, D.A.; Screen, H.R.C.; Shaheed, M.H. Development of a two-stage gene selection method that incorporates a novel hybrid approach using the cuckoo optimization algorithm and harmony search for cancer classification. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 67, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeg, H.J.; Moutou, C.; Erikson, A.; Csizmadia, S.; Tingley, B.; Barge, P.; Bruntt, H.; Havel, M.; Aigrain, S.; Almenara, J.M.; et al. A transiting giant planet with a temperature between 250 K and 430 K. Nature 2010, 464, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geem, Z.W.; Choi, J.Y. Music Composition Using Harmony Search Algorithm. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2007, 4448, 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, M.; Corchado, J.M.; Demazeau, Y. MUSIC-MAS: Modeling a harmonic composition system with virtual organizations to assist novice composers. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 57, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenderink, J.; van Doorn, A.; Wagemans, J. Picasso in the mind’s eye of the beholder: Three-dimensional filling-in of ambiguous line drawings. Cognition 2012, 125, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geem, Z.W. Harmony Search Algorithm for Solving Sudoku. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2007, 4692, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Geem, Z.W. Music-Inspired Harmony Search Algorithm: Theory and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manjarres, D.; Landa-Torres, I.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Del Ser, J.; Bilbao, M.N.; Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Geem, Z.W. A Survey on Applications of the Harmony Search Algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2013, 26, 1818–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarzadeh, A. Solving electrical power system problems by harmony search: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2017, 47, 217–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lu, C.; Li, G. A literature review on latest developments of Harmony Search and its applications to intelligent manufacturing. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2019, 16, 2086–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala’a, A.; Alsewari, A.A.; Alamri, H.S.; Zamli, K.Z. Comprehensive Review of the Development of the Harmony Search Algorithm and Its Applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 14233–14245. [Google Scholar]

- Alia, M.; Mandava, R. The variants of the harmony search algorithm: An overview. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2011, 36, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Z.; Govindasamy, V.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Zenger, K. Harmony Search Method: Theory and Applications. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2015, 2015, 258491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, H.-G. On the dynamics of EAs without selection. In Foundations of Genetic Algorithms; Banzhaf, W., Reeves, C., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 5, pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Roy, A.; Abraham, A. Exploratory Power of the Harmony Search Algorithm: Analysis and Im-provements for Global Numerical Optimization. IEEE Trans. Sys. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. 2001, 41, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F.J. On the convergence properties of the EM algorithm. Ann. Stat. 1983, 11, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, A.D. Convergence Rates of Efficient Global Optimization Algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2879–2904. [Google Scholar]

- Trelea, I.C. The particle swarm optimization algorithm: Convergence analysis and parameter selection. Inf. Process. Lett. 2003, 85, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, R.; Qiu, J.; Jin, Y. A competitive mechanism based multi-objective particle swarm optimizer with fast convergence. Inf. Sci. 2018, 427, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinei, F.; Júdice, J.; Soares, J. Generating Box-Constrained Optimization Problems. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1997, 23, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geem, Z.W. Novel derivative of harmony search algorithm for discrete design variables. Appl. Math. Comp. 2008, 199, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Geem, Z.W. Review of Harmony Search with Respect to Algorithm Structure. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2019, 48, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Giménez, D.; López-Espín, J.J.; Pérez-Pérez, M. Parameterized Schemes of Metaheuristics: Basic Ideas and Applications with Genetic Algorithms, Scatter Search, and GRASP. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2013, 43, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, J.H.; Geem, Z.W. Empirical Convergence Theory of Harmony Search Algorithm for Box-Constrained Discrete Optimization of Convex Function. Mathematics 2021, 9, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9050545

Yoon JH, Geem ZW. Empirical Convergence Theory of Harmony Search Algorithm for Box-Constrained Discrete Optimization of Convex Function. Mathematics. 2021; 9(5):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9050545

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Jin Hee, and Zong Woo Geem. 2021. "Empirical Convergence Theory of Harmony Search Algorithm for Box-Constrained Discrete Optimization of Convex Function" Mathematics 9, no. 5: 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9050545

APA StyleYoon, J. H., & Geem, Z. W. (2021). Empirical Convergence Theory of Harmony Search Algorithm for Box-Constrained Discrete Optimization of Convex Function. Mathematics, 9(5), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9050545