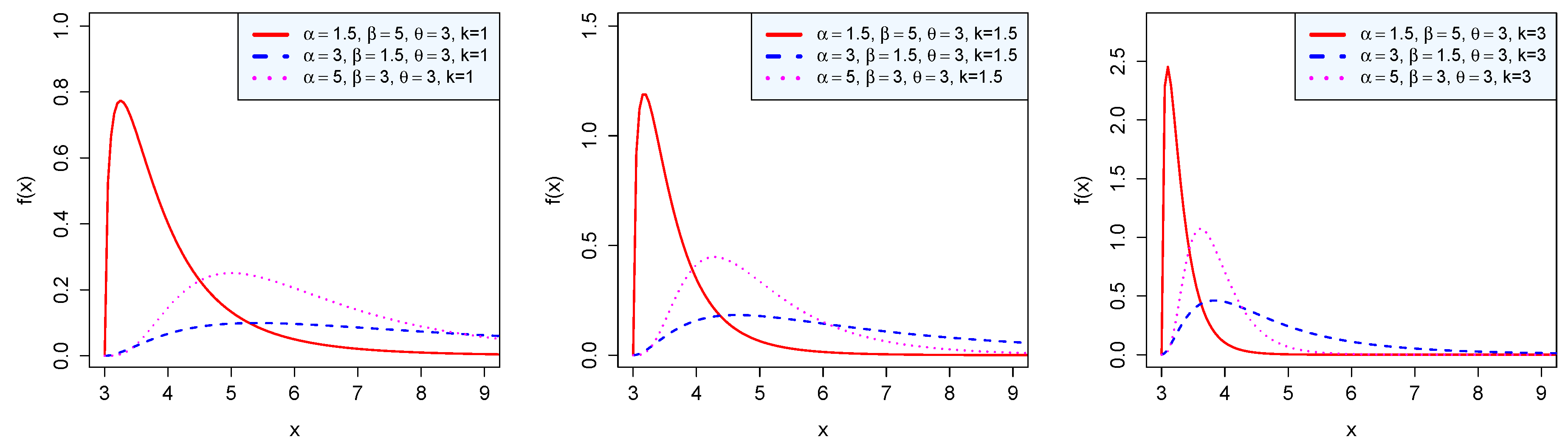

Figure 1.

Density of the BP distribution.

Figure 1.

Density of the BP distribution.

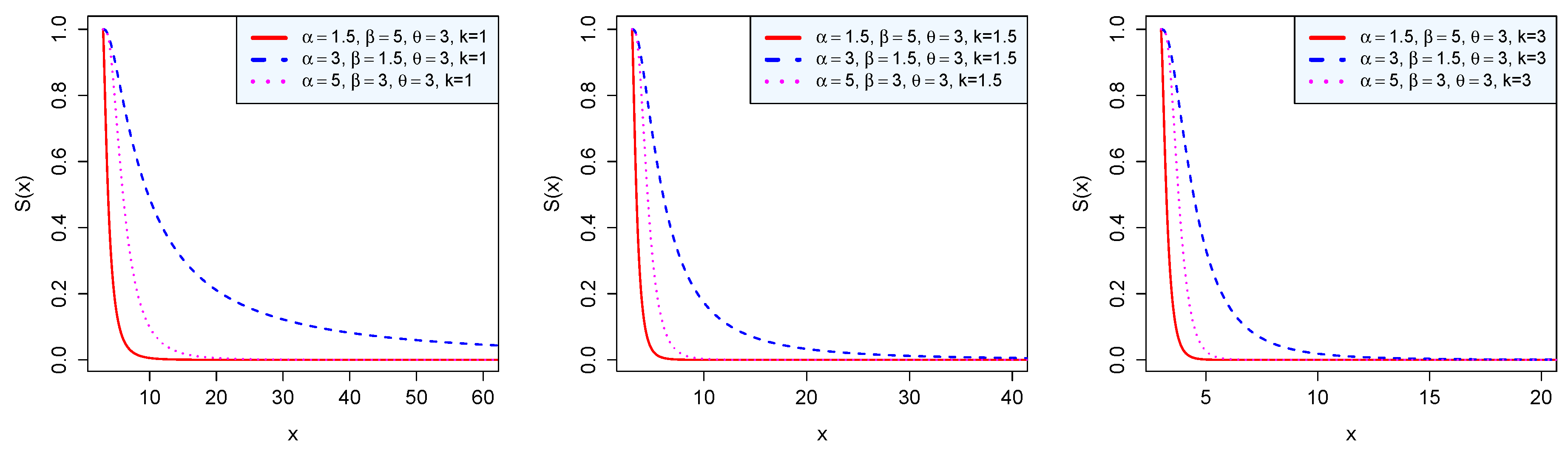

Figure 2.

Survival function of the BP distribution.

Figure 2.

Survival function of the BP distribution.

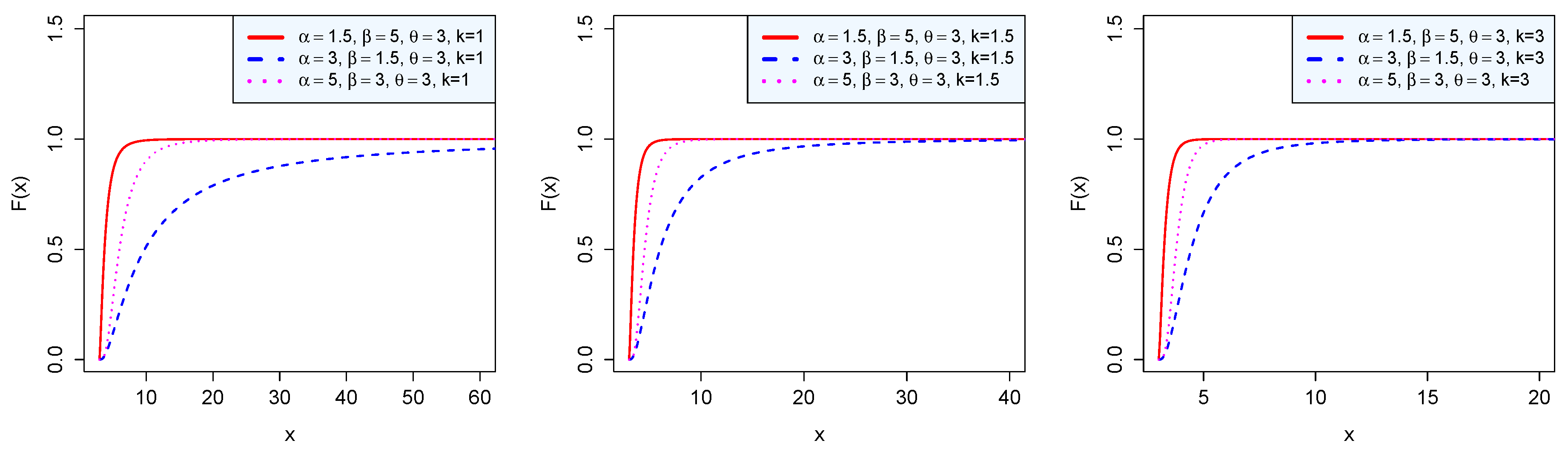

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution function of the BP distribution.

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution function of the BP distribution.

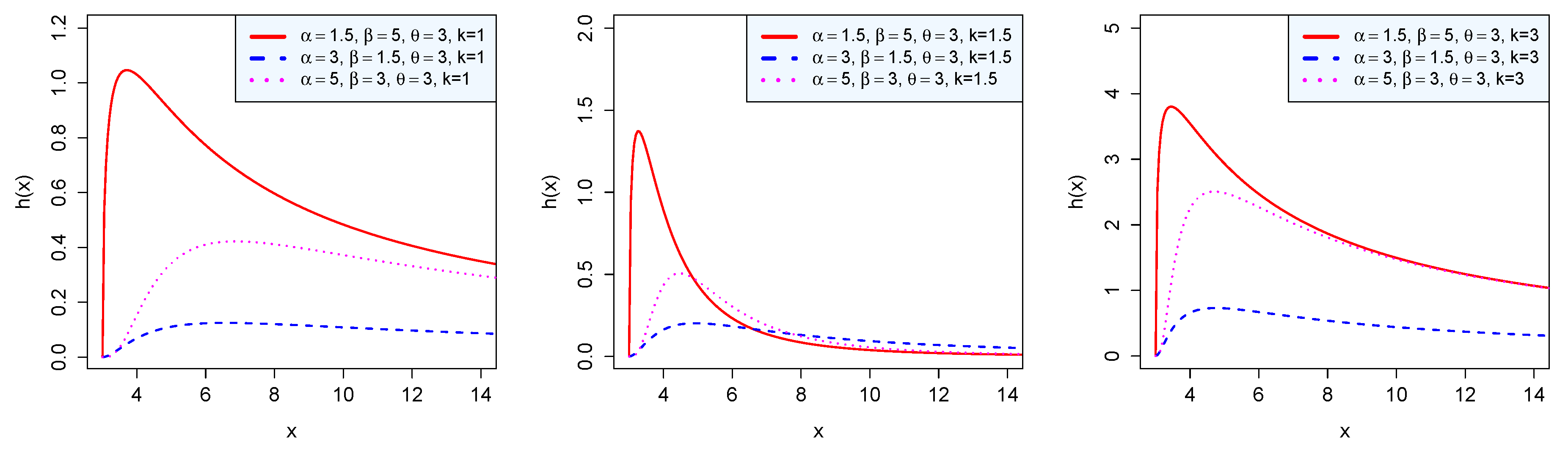

Figure 4.

Hazard rate of the BP distribution.

Figure 4.

Hazard rate of the BP distribution.

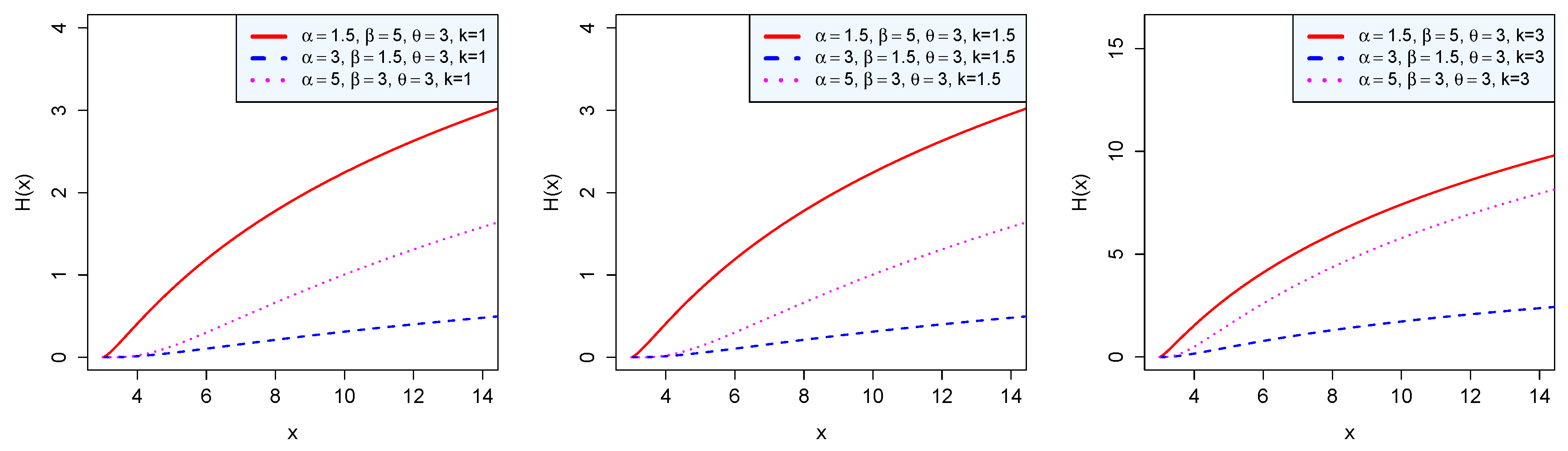

Figure 5.

Cumulative hazard rate of the BP distribution.

Figure 5.

Cumulative hazard rate of the BP distribution.

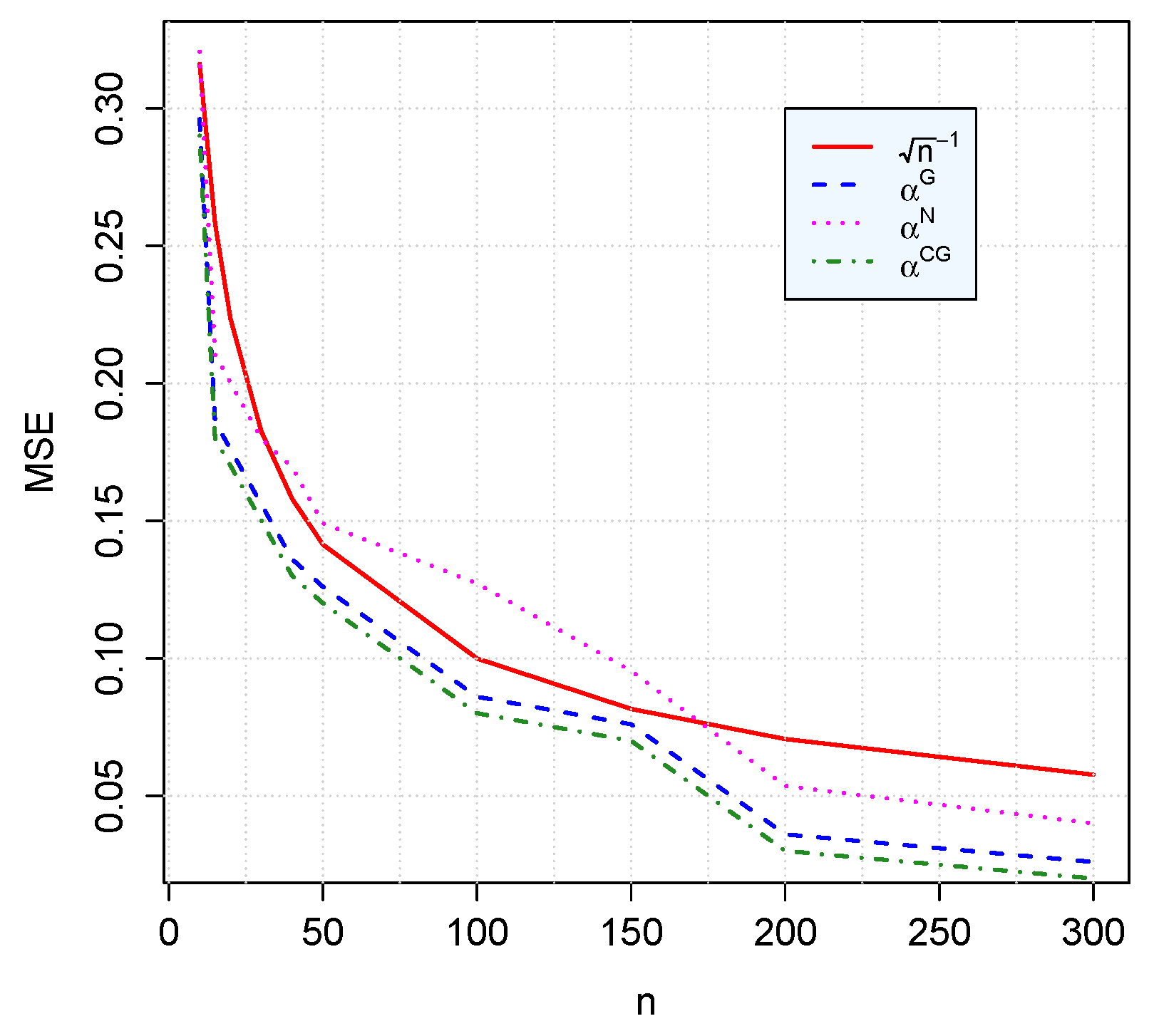

Figure 6.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

Figure 6.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

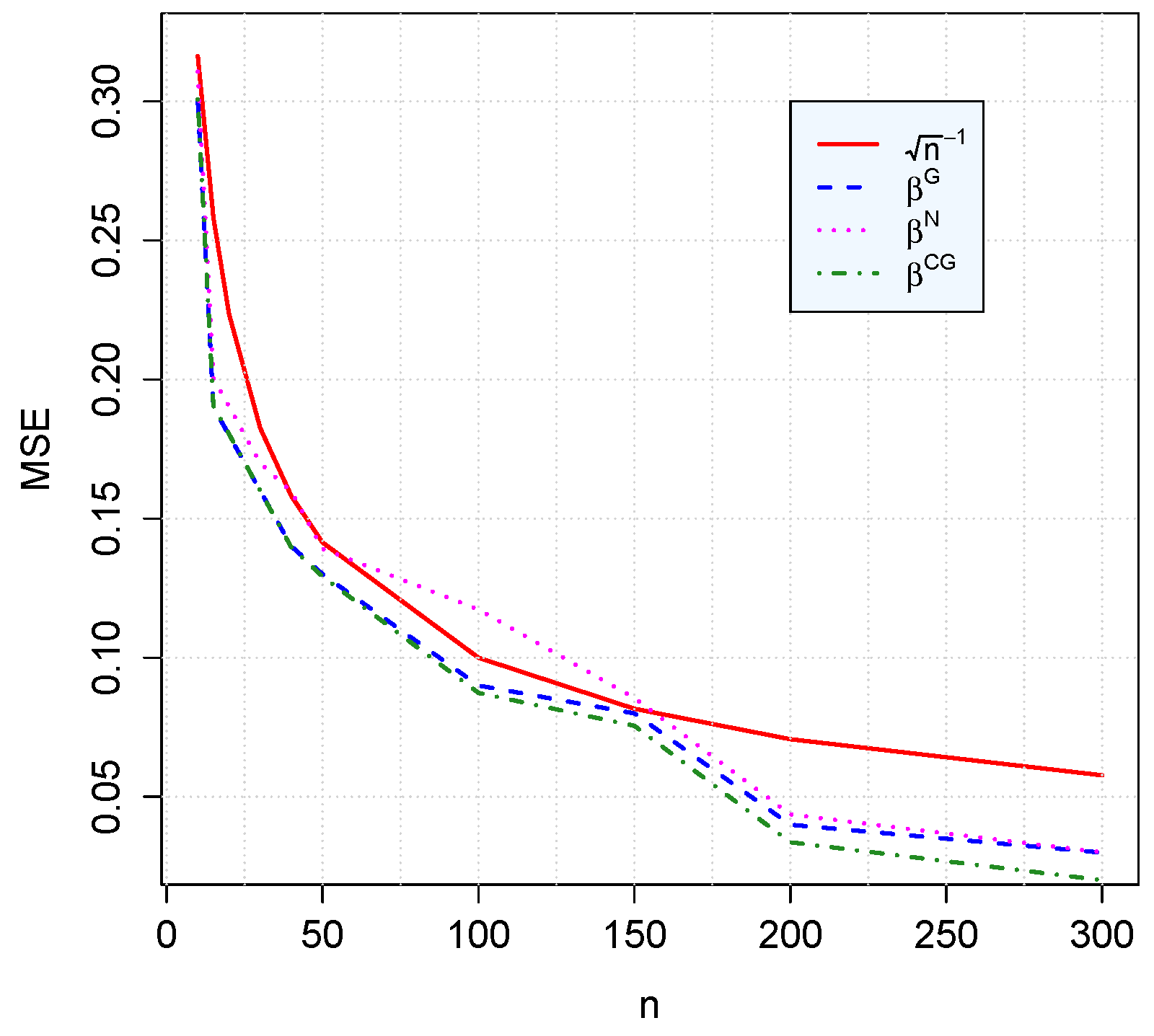

Figure 7.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

Figure 7.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

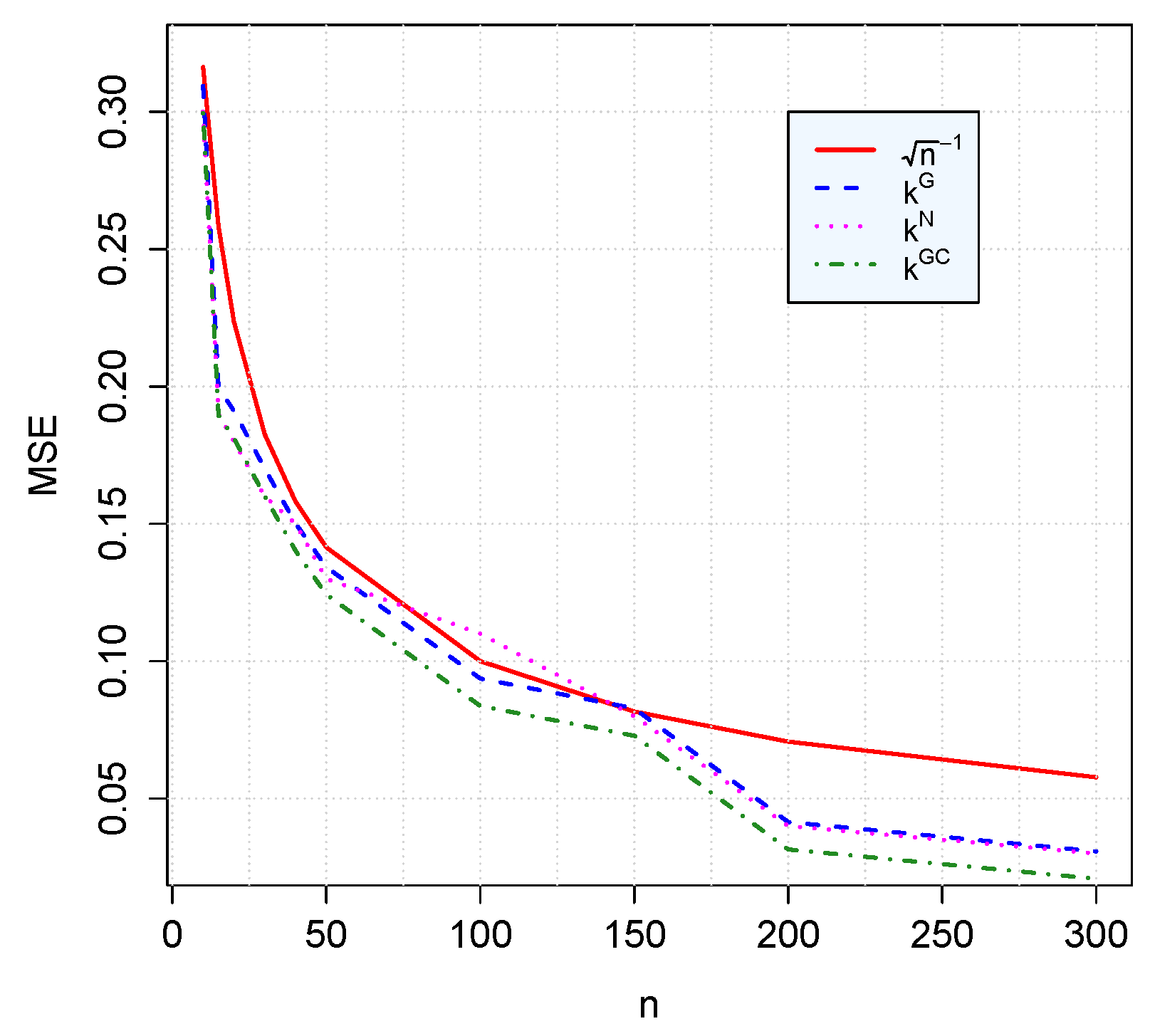

Figure 8.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

Figure 8.

The MSE of computed with Newton’s, gradient and conjugate gradient methods.

Table 1.

Results of simulation with conjugate gradient method for 10,000 iterations, with

Table 1.

Results of simulation with conjugate gradient method for 10,000 iterations, with

| n | | | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 22.7873 | 33.7865 | 19.9800 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 9.44 |

| 15 | 22.7910 | 33.7902 | 19.9802 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 9.47 |

| 20 | 22.7947 | 33.7939 | 19.9804 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.11 |

| 30 | 22.8020 | 33.8012 | 19.9808 | 9.89 | 9.97 | 1.01 |

| 40 | 22.8094 | 33.8086 | 19.9812 | 9.52 | 9.62 | 1.02 |

| 50 | 22.8168 | 33.8160 | 19.9906 | 9.15 | 9.17 | 4.26 |

| 100 | 22.8536 | 33.8528 | 19.9926 | 7.31 | 7.35 | 3.72 |

| 150 | 22.8904 | 33.8896 | 19.9946 | 5.47 | 5.52 | 2.83 |

| 200 | 22.9273 | 33.9265 | 19.9966 | 3.63 | 3.65 | 1.45 |

| 300 | 23.0009 | 34.0001 | 20.0006 | 4.78 | 4.01 | 8.09 |

Table 2.

Results of simulation with gradient method for 10,000 iterations, with .

Table 2.

Results of simulation with gradient method for 10,000 iterations, with .

| n | | | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 22.7873 | 33.7865 | 19.7790 | 2.12 | 2.12 | 2.20 |

| 15 | 22.7910 | 33.7902 | 19.7992 | 2.08 | 2.09 | 1.99 |

| 20 | 22.7947 | 33.7939 | 19.7994 | 2.05 | 2.06 | 2.00 |

| 30 | 22.8020 | 33.8012 | 19.7998 | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.99 |

| 40 | 22.8094 | 33.8086 | 19.8002 | 1.90 | 1.90 | 1.98 |

| 50 | 22.8168 | 33.8160 | 19.8126 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 1.86 |

| 100 | 22.8536 | 33.8528 | 19.9026 | 1.46 | 1.47 | 9.76 |

| 150 | 22.8904 | 33.8896 | 19.9046 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 9.69 |

| 200 | 22.9273 | 33.9265 | 19.9066 | 7.26 | 7.32 | 9.30 |

| 300 | 23.0009 | 34.0001 | 19.9106 | 9.56 | 8.21 | 8.83 |

Table 3.

Results of simulation with Newton’s method for 10,000 iterations, with .

Table 3.

Results of simulation with Newton’s method for 10,000 iterations, with .

| n | | | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 22.5508 | 33.4207 | 19.6611 | 2.01 | 3.35 | 1.14 |

| 15 | 22.5508 | 33.4207 | 19.6611 | 1.34 | 2.23 | 7.65 |

| 20 | 22.5508 | 33.420 | 19.6684 | 1.01 | 1.67 | 5.49 |

| 30 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8198 | 6.72 | 7.42 | 1.08 |

| 40 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8243 | 5.04 | 5.56 | 7.71 |

| 50 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8239 | 4.03 | 4.45 | 1.03 |

| 100 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8198 | 2.01 | 2.22 | 1.03 |

| 150 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8197 | 1.34 | 1.48 | 2.16 |

| 200 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8197 | 2.62 | 1.11 | 1.62 |

| 300 | 22.7707 | 33.8507 | 19.8197 | 1.75 | 7.42 | 1.08 |

Table 4.

MLEs of with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

Table 4.

MLEs of with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

|

|---|

| | (bias) | MSE |

|---|

| n | (bias) | (bias) | | |

|---|

| 10 | 22.787 (0.220) | 23.009786028 (−0.0097860) | 1.36 | 3.58 |

| 20 | 22.794 (0.205) | 23.009786227 (−0.0097862) | 5.44 | 3.58 |

| 30 | 22.802 (0.197) | 23.009786057 (−0.0097860) | 1.22 | 3.58 |

| 40 | 22.802 (0.197) | 23.009786022 (−0.0097860) | 1.22 | 3.58 |

| 50 | 22.809 (0.190) | 23.009786225 (−0.0097862) | 9.89 | 3.58 |

| 100 | 22.809 (3.4 ) | 23.009786237 (−0.009786) | 9.89 | 3.58 |

| 150 | 22.816 (0.109) | 23.009786240 (−0.009786) | 3.06 | 3.58 |

| 200 | 22.890 (0.072) | 23.009786240 (−0.009786) | 5.44 | 3.58 |

| 300 | 23.001 (−0.001) | 23.009786241 (−0.009786) | 1.22 | 3.58 |

| 1000 | 23.002 (−0.002) | 23.009786241 (−0.009786) | 1.37 | 3.58 |

Table 5.

MLEs of with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

Table 5.

MLEs of with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

|

|---|

| | (bias) | MSE |

|---|

| n | (bias) | (bias) | | |

|---|

| 10 | 33.786 (0.006) | 33.9995 (0.000409) | 1.27 | 3.57 |

| 20 | 33.793 (0.206) | 33.9997 (0.000225) | 5.04 | 3.58 |

| 30 | 33.801 (0.198) | 33.9996 (0.000348) | 8.76 | 3.57 |

| 40 | 33.801 (0.198) | 33.9996 (0.000364) | 1.22 | 3.57 |

| 50 | 33.808 (0.191) | 33.9997 (0.000229) | 2.13 | 3.58 |

| 100 | 33.816 (0.183) | 33.9997 (0.00022) | 1.65 | 3.58 |

| 150 | 33.889 (0.110) | 33.9997 (0.000217) | 3.06 | 3.58 |

| 200 | 33.926 (0.073) | 33.9997 (0.000218) | 5.41 | 3.58 |

| 300 | 34.000 (−0.0006) | 33.9997 (0.000217) | 1.21 | 3.58 |

| 1000 | 34.001 (0.001) | 33.9997 (0.000217) | 1.37 | 3.58 |

Table 6.

MLEs of k with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

Table 6.

MLEs of k with the conjugate gradient method and gradient method.

| k |

|---|

| | (bias) | MSE |

|---|

| n | (bias) | (bias) | | |

|---|

| 10 | 19.989 (0.0001) | 20.046 (−0.046) | 1.98 | 4.40 |

| 20 | 19.989 (0.0105) | 20.037 (−0.037) | 1.48 | 3.50 |

| 30 | 19.989 (0.0101) | 20.042 (−0.042) | 1.74 | 3.82 |

| 40 | 19.989 (0.0102) | 20.041 (−0.041) | 1.43 | 3.77 |

| 50 | 19.990 ( 0.0096) | 20.037 (0.037) | 1.00 | 3.52 |

| 100 | 19.990 (0.0094) | 20.037 (0.037) | 9.89 | 3.53 |

| 150 | 19.994 (0.0054) | 20.037 (0.037) | 1.65 | 3.53 |

| 200 | 19.996 (0.0032) | 20.037 (0.037) | 1.16 | 3.53 |

| 300 | 23.001 (−0.0014) | 20.037 (−0.037) | 1.67 | 3.58 |

| 1000 | 20.000 (−0.0006) | 20.037 (−0.037) | 3.10 | 3.53 |

Table 7.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a GBP distribution with .

Table 7.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a GBP distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 222 | 712 | 21 | 19 | 26 | 229 | 719 | 13 | 17 | 22 | 227 | 753 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| 20 | 156 | 784 | 13 | 17 | 30 | 179 | 710 | 7 | 13 | 91 | 176 | 784 | 2 | 3 | 30 |

| 30 | 145 | 567 | 10 | 15 | 263 | 155 | 603 | 4 | 11 | 227 | 151 | 784 | 1 | 7 | 57 |

| 50 | 96 | 278 | 8 | 12 | 606 | 106 | 307 | 3 | 7 | 577 | 111 | 604 | 0 | 5 | 244 |

| 100 | 43 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 909 | 43 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 897 | 43 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 727 |

| 200 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 962 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 962 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 959 |

| 300 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 980 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 980 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 980 |

| 500 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 995 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 995 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 995 |

| 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 |

Table 8.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a Pareto distribution with .

Table 8.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a Pareto distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 70 | 26 | 7 | 783 | 3 | 181 | 21 | 11 | 915 | 5 | 48 | 23 | 10 | 964 | 2 | 1 |

| 80 | 12 | 3 | 786 | 0 | 199 | 19 | 2 | 909 | 1 | 69 | 13 | 4 | 976 | 1 | 6 |

| 90 | 4 | 0 | 780 | 0 | 216 | 7 | 0 | 912 | 0 | 81 | 3 | 0 | 997 | 0 | 10 |

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 970 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 995 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 992 | 0 | 8 |

| 150 | 0 | 0 | 974 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 996 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 997 | 0 | 3 |

| 200 | 0 | 0 | 980 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 996 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 0 | 2 |

| 300 | 0 | 0 | 984 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 997 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 0 | 2 |

| 500 | 0 | 0 | 992 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 995 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 0 | 2 |

| 1000 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 |

Table 9.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a Gamma distribution with .

Table 9.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a Gamma distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 988 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 988 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 989 | 0 |

| 20 | 3 | 13 | 9 | 947 | 28 | 4 | 21 | 12 | 972 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 600 | 385 |

| 30 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 893 | 85 | 4 | 13 | 9 | 957 | 17 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 793 | 195 |

| 50 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 823 | 160 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 962 | 25 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 950 | 44 |

| 100 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 779 | 209 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 955 | 72 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 980 | 19 |

| 150 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 807 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 914 | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 977 | 23 |

| 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 776 | 224 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 898 | 102 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 988 | 12 |

| 500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 843 | 157 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 906 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 2 |

| 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 915 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 949 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 2 |

| 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 975 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 982 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 998 | 2 |

Table 10.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a BP distribution with .

Table 10.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a BP distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 560 | 19 | 0 | 421 | 0 | 558 | 20 | 0 | 422 | 0 | 525 | 29 | 0 | 446 | 0 |

| 20 | 648 | 1 | 0 | 351 | 0 | 645 | 1 | 0 | 354 | 0 | 620 | 3 | 0 | 377 | 0 |

| 30 | 48 | 1 | 0 | 351 | 0 | 645 | 1 | 0 | 354 | 0 | 620 | 3 | 0 | 377 | 0 |

| 50 | 648 | 1 | 0 | 351 | 0 | 645 | 1 | 0 | 354 | 0 | 620 | 3 | 0 | 377 | 0 |

| 100 | 873 | 0 | 0 | 127 | 0 | 871 | 0 | 0 | 129 | 0 | 820 | 0 | 0 | 180 | 0 |

| 150 | 890 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 0 | 888 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 844 | 0 | 0 | 156 | 0 |

| 200 | 931 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 931 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 892 | 0 | 0 | 108 | 0 |

| 500 | 962 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 962 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 928 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 0 |

| 1000 | 999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 998 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 2000 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 11.

Results of simulation with samples of censored data using the conjugate gradient method with .

Table 11.

Results of simulation with samples of censored data using the conjugate gradient method with .

| n | | | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 12.0111 | 23.5087 | 17.7891 | 1.701444 | 0.766839 | 0.036204 |

| 15 | 12.0541 | 23.8580 | 17.7891 | 0.733933 | 0.659689 | 0.036204 |

| 20 | 12.0967 | 23.9454 | 17.7891 | 0.183483 | 0.476273 | 0.036204 |

| 30 | 12.0106 | 23.4682 | 18.0907 | 0.117429 | 0.067367 | 0.036204 |

| 40 | 12.2676 | 23.5793 | 18.0907 | 0.007339 | 0.137393 | 0.036204 |

| 50 | 12.3533 | 23.1487 | 18.0907 | 8.39 | 8.67 | 4.71 |

| 100 | 12.7817 | 23.0266 | 18.0907 | 8.47 | 8.83 | 4.71 |

| 150 | 12.8293 | 22.9632 | 18.0907 | 8.55 | 9.50 | 4.71 |

| 200 | 12.8940 | 22.8416 | 17.8626 | 4.78 | 4.01 | 8.09 |

| 300 | 12.9777 | 22.7847 | 17.8277 | 1.58 | 4.66 | 3.33 |

| 500 | 12.9785 | 22.8175 | 17.8626 | 2.85 | 9.44 | 3.35 |

| 1000 | 13.0002 | 23.0004 | 17.0073 | 7.00 | 1.19 | 5.69 |

Table 12.

Results of simulation with samples of censored data using the gradient method with 10,000, .

Table 12.

Results of simulation with samples of censored data using the gradient method with 10,000, .

| n | | | | | | |

|---|

| 10 | 12.8685 | 22.9473 | 15.9886 | 0.000319 | 0.000527 | 0.001948 |

| 15 | 12.9168 | 22.9444 | 16.8106 | 7.03 | 9.83 | 2.82 |

| 20 | 12.9336 | 22.9669 | 16.2010 | 2.11 | 1.00 | 9.67 |

| 30 | 12.9336 | 23.0119 | 16.8935 | 2.11 | 5.79 | 3.35 |

| 40 | 12.9336 | 23.0095 | 16.8626 | 2.12 | 3.88 | 3.15 |

| 50 | 12.9420 | 23.0256 | 17.4303 | 2.82 | 1.80 | 5.93 |

| 100 | 12.9504 | 22.9386 | 17.4201 | 3.52 | 7.21 | 4.68 |

| 150 | 12.9588 | 22.9327 | 17.7439 | 4.22 | 7.24 | 5.72 |

| 200 | 12.9672 | 22.9290 | 18.0424 | 4.93 | 6.92 | 6.61 |

| 300 | 12.9756 | 22.9404 | 18.3535 | 5.63 | 4.24 | 7.58 |

| 500 | 12.9756 | 22.9381 | 19.7080 | 5.63 | 4.08 | 8.82 |

| 1000 | 12.9840 | 23.0030 | 19.7933 | 6.35 | 2.29 | 1.05 |

Table 13.

Gradient method.

Table 13.

Gradient method.

| | | | |

|---|

| E() | 12.9450 | 22.9656 | 17.6040 |

| bias | −0.0242 | −0.0349 | 0.3027 |

| MSE | 5.66 | 1.41 | 7.27 |

Table 14.

Conjugate gradient method.

Table 14.

Conjugate gradient method.

| | | | |

|---|

| E() | 13.0029 | 23.002452 | 17.9714 |

| bias | −0.0790 | 0.0261 | 0.0328 |

| MSE | 1.82 | 3.90 | 3.42 |

Table 15.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored Pareto distribution with .

Table 15.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored Pareto distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 7 | 10 | 233 | 745 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 233 | 748 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 233 | 738 | 15 |

| 20 | 5 | 12 | 417 | 563 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 417 | 570 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 417 | 559 | 11 |

| 30 | 1 | 7 | 561 | 429 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 561 | 425 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 561 | 428 | 3 |

| 50 | 0 | 5 | 734 | 261 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 734 | 265 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 734 | 264 | 0 |

| 100 | 0 | 2 | 912 | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 912 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 912 | 87 | 0 |

| 200 | 0 | 0 | 939 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 939 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 939 | 61 | 0 |

| 500 | 0 | 0 | 973 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 973 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 973 | 27 | 0 |

| 1000 | 0 | 0 | 996 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 996 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 996 | 4 | 0 |

Table 16.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored Gamma distribution with .

Table 16.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored Gamma distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 936 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 936 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 936 | 0 |

| 30 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 947 | 0 |

| 50 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 937 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 937 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 937 | 0 |

| 100 | 0 | 1 | 56 | 943 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 56 | 943 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 56 | 943 | 0 |

| 200 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 946 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 946 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 946 | 0 |

| 500 | 0 | 1 | 53 | 946 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 | 947 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 53 | 946 | 0 |

| 1000 | 0 | 1 | 61 | 938 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 939 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 61 | 938 | 0 |

Table 17.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored BP distribution with .

Table 17.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored BP distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 453 | 11 | 25 | 502 | 9 | 434 | 7 | 24 | 524 | 11 | 421 | 12 | 22 | 579 | 7 |

| 20 | 600 | 8 | 15 | 370 | 7 | 532 | 6 | 15 | 438 | 9 | 531 | 15 | 10 | 439 | 5 |

| 30 | 636 | 7 | 9 | 344 | 4 | 598 | 5 | 8 | 382 | 7 | 611 | 12 | 6 | 369 | 2 |

| 50 | 704 | 3 | 6 | 286 | 1 | 665 | 2 | 7 | 323 | 3 | 688 | 7 | 2 | 302 | 1 |

| 100 | 711 | 0 | 0 | 289 | 0 | 680 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 0 | 699 | 0 | 0 | 301 | 0 |

| 200 | 714 | 0 | 0 | 286 | 0 | 682 | 0 | 0 | 318 | 0 | 708 | 0 | 0 | 298 | 0 |

| 500 | 741 | 0 | 0 | 259 | 0 | 736 | 0 | 0 | 264 | 0 | 741 | 0 | 0 | 259 | 0 |

| 1000 | 752 | 0 | 0 | 248 | 0 | 748 | 0 | 0 | 252 | 0 | 752 | 0 | 0 | 248 | 0 |

| 2000 | 755 | 0 | 0 | 245 | 0 | 753 | 0 | 0 | 247 | 0 | 755 | 0 | 0 | 245 | 0 |

Table 18.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored GBP distribution with .

Table 18.

Smaller AIC/BIC/AICc scores in 1000 simulations from a censored GBP distribution with .

| AIC | BIC | AICc |

|---|

| n | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP | BP | B | P | G | GBP |

|---|

| 10 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 994 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 994 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 994 |

| 20 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 989 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 990 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 989 |

| 30 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 988 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 990 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 988 |

| 50 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 980 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 980 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 980 |

| 100 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 975 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 975 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 975 |

| 200 | 33 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 965 | 33 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 965 | 34 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 964 |

| 300 | 53 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 943 | 51 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 945 | 52 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 944 |

| 500 | 76 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 923 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 924 | 76 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 923 |

| 1000 | 122 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 876 | 118 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 880 | 123 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 877 |

| 2000 | 238 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 760 | 237 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 761 | 237 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 761 |