Abstract

Cumulative sum control charts that are based on the estimated control limits are extensively used in practice. Such control limits are often characterized by a Phase I estimation error. The presence of these errors can cause a change in the location and/or width of control limits resulting in a deprived performance of the control chart. In this study, we introduce a non-parametric Tukey’s outlier detection model in the design structure of a two-sided cumulative sum (CUSUM) chart with estimated parameters for process monitoring. Using Monte Carlo simulations, we studied the estimation effect on the performance of the CUSUM chart in terms of the average run length and the standard deviation of the run length. We found the new design structure is more stable in the presence of outliers and requires fewer amounts of Phase I observations to stabilize the run-length performance. Finally, a numerical example and practical application of the proposed scheme are demonstrated using a dataset from healthcare surveillance where received signal strength of individuals’ movement is the variable of interest. The implementation of classical CUSUM shows that a shift detection in Phase II that received signal strength data is indeed masked/delayed if there are outliers in Phase I data. On the contrary, the proposed chart omits the Phase I outliers and gives a timely signal in Phase II.

1. Introduction

The cumulative sum (CUSUM) control chart is an effective monitoring tool widely used in industries and medical processes for quality improvement [1]. The scheme was introduced by [2] as the substitution of the traditional Shewhart control chart. The CUSUM chart statistic accumulates the past and current information of the process, which provides more sensitivity to detect small and moderate shifts as compared to the traditional Shewhart control chart. Designing a CUSUM control chart requires setting up of the control limit, where the known in-control parameters are often assumed. However, this assumption is not realistic, and hence the CUSUM chart is implemented in a two-phase method. In Phase I, random observations are collected from a stable process and used to estimate the unknown parameters. In Phase II, the estimates from the earlier observations are used for the construction of the CUSUM chart to monitor and detect changes in a process [3].

The performance of a CUSUM chart to effectively handle changes in the process in Phase II largely depends on the accuracy of the estimated parameters in Phase I. Furthermore, higher chances of estimation error may occur when there exist some extreme values or outliers in the Phase I observations [4]. Outliers may occur by chance in the process data or could be due to some incorrect specifications of instruments or as a result of human reporting error. The presence of outliers in a process data can adversely affect parametric computations. Of course, dropping the outliers from the sampled observations is the simplest remedy often used to avoid such a problem. However, this may not be appropriate for small sample data. Thus, outlier detection is key to adequate monitoring of process parameters. Recently, some non-parametric and robust outlier detection procedures have been suggested to enhance the performance of control charts in the presence of outliers. For example, see Schoonhoven, Nazir [5], Nazir, Riaz [6], Amdouni, Castagliola [7], Abid, Nazir [8], Zhang, Li [9] and Mahmood, Nazir [10], and the references therein.

Hawkins [11], Beckman and Cook [12] and Barnett and Lewis [13] have studied several outlier detectors. The common parametric outlier detectors are the Student-type and Grubbs-type detectors mostly used in the regression residuals and when the data is normally distributed (cf. Grubbs [14] and Tietjen and Moore [15]). For non-normal data, the Tukey’s outlier detection model is more robust since its independence of the sample mean and standard deviation [16]. Teoh, Khoo [17] suggested the local outlier factor, a non-parametric outlier detector for detecting the outliers in the multivariate setup. Knorr, Ng [18] designed a detector based on classification methodology while a detector based on order statistics was studied by Tse and Balasooriya [19]. Hubert, Dierckx [20] proposed a procedure based on Hill’s estimator for detecting the influential point in Pareto-type distributions. Recently, Castagliola, Amdouni [21] introduced a new non-parametric outlier detector for all types of univariate distributions.

In this article, we study the effect of outliers on the performance of a two-sided CUSUM control chart for monitoring process location with the estimated parameters using the run length (RL) properties. Furthermore, the study proposed a non-parametric outlier detector, the robust Tukey outlier detection model in the design structure of a CUSUM control chart for efficient monitoring of the process location parameters in the presence of the extremes. These measures are evaluated in three cases. The first case is when the in-control mean is known, and the standard deviation is estimated. Second is when the in-control standard deviation is known, and the mean is estimated, and the third case is when both the mean and the standard deviation are unknown. A synthesis table about the research on a two-sided CUSUM chart is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

A synthesis table for the past and current research on a two-sided cumulative sum (CUSUM) chart.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In the next section, we gave overview information on the two-sided CUSUM chart with estimated parameters followed by the performance measure metrics in terms of the RL properties. Section 3 presents the practitioner-to-practitioner variation on the performance of the CUSUM chart. The section also discusses the effect of error estimation on CUSUM control limits. In Section 4, we gave the design structure of the CUSUM chart in the presence of outliers and analyzed the effect of extremes on its in-control performance. The introduction of the Tukey outlier detection model in the CUSUM chart is presented in Section 5. An application example to illustrate the practical use of the scheme is given in Section 6. Finally, we provide some concluding remark in Section 7.

2. Overview of CUSUM Charts with Estimated Parameters

Let . for be independent random observations of size from a normal process, with a known in-control mean and standard deviation . The upper and lower sided CUSUM chart statistics for monitoring the upward and downward changes in the process location parameters are respectively, given by

where and are the maximum and minimum of and , respectively. The statistic, is the mean of sample, and is the reference value. The initial values, and , are usually set equal to zero. The chart gives an out-of-control signal when either or exceeds the predetermined control limit, . The is usually chosen to satisfy the desired in-control RL property.

However, if the process parameters are unknown, then and are replaced by their corresponding Phase I estimates. Let , and denote random samples each of size of Phase I observations from a stable process. Then the unbiased estimator for , is the overall sample mean given by

and for the unbiased estimator of when subgroup size , we used the pooled standard deviation,

recommended by some researchers like Chen [22], Mahmoud, Henderson [23] and Nazir, Abbas [24]. Here, is the variance the of Phase I sample. The unbiased estimator is defined by

where the constant, is the bias correction constant that depends on the and . Thus, the corresponding two-sided CUSUM chart statistics based on the estimated parameters are defined as

The statistical performance of a CUSUM chart is often evaluated in terms of its RL distribution [25]. For a two-sided CUSUM chart with initial value of , where , the probability mass function [26] is given by

For a single case, , we have

where , , , and denotes the standard normal distribution function. For the case when , we have

where is the standard normal density function. The most common used RL property to evaluate the performance of a control chart is the average run length (ARL), which represents the average number of samples plotted on a control chart before a process issues a signal. The ARL measures how quickly a control chart responds to changes in a process. If Equation (7) is denoted by , for simplicity, then the ARL can be defined by the integral equation [26,27].

where is the scaled chi distribution with degrees of freedom from , and is a scaled factor. There is also the standard deviation of run length (SDRL) that sometimes is used as a supplementary measure. The SDRL is the standard deviation of samples until the chart gives an out-of-control signal, that is,

where . For an in-control process, denote the ARL by , which in practice, should be sufficiently large to avoid unnecessary false signals. Furthermore, denote the out-of-control ARL by , which should be small enough to enable early detection of changes in a process. The above RL properties of a two-sided CUSUM chart may be obtained by evaluating , but unfortunately, it cannot be computed exactly. Hence, the need for approximation using either Gaussian quadrature, Markov chain approximation or Monte Carlo simulation. With the technological advancements in computing software, we followed the simulation approach as recommended by several authors of the quality control chart.

3. Variability in the CUSUM Chart Performance

For the location control chart, the process is assumed to be initially stable with an in-control mean and standard deviation . After a certain point in time, it changes from the target value to an out-of-control value thus, requiring immediate and quick detection of such changes. Without loss of generality, we assumed that the in-control process is normally distributed. To study the so-called practitioner-to-practitioner variation on the performance of the CUSUM chart, 100,000 seeded iterations, each sample size , were generated from the standard normal distribution . We then set up the charts with and , using the combinations of the control limit and that corresponds to the in-control of . We used the simulation approach based on an algorithm developed in R, to compute the distributional properties of the CUSUM chart in terms of the ARL and SDRL for different shift values when the control chart parameters and are known and the results obtained are presented in Table 2. These results are in agreement with the theoretical values of a classical two-sided CUSUM chart [2].

Table 2.

Run length (RL) properties for the two-sided CUSUM control chart when the in-control mean and standard deviation are known .

The unknown in-control process parameters, on the other hand, are estimated from and in-control Phase I samples each of subgroup size . Substituting the unknown parameters with their corresponding estimates, the Phase II two-sided CUSUM control charts were developed. For each fixed value of and , the control limit was determined through simulations to obtain the desired in-control of . Here, all the observations are from . The ARL and SDRL values are computed using 100,000 simulation iterations. For a clear consequence on the effect of each estimated process parameter on the performance of a CUSUM chart, we considered the cases when either the sample mean or sample standard deviation or both were estimated. Results obtained are given in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

RL properties for the two-sided CUSUM control chart when the in-control standard deviation is known, and mean is estimated .

Table 4.

RL properties for the two-sided CUSUM control chart when the in-control mean is known, and the standard deviation is estimated .

Table 5.

RL properties for the two-sided CUSUM control chart when the in-control mean and standard deviation are estimated .

3.1. Effect of Estimation on the Two-Sided CUSUM Chart Performance

Results in Table 2 and Table 3 shows that a small number of Phase I samples, produced out-of-control ARL and SDRL values (cf. Table 3) that were higher than the known standard values in Table 2, for a fixed . This is an indication that the use of small Phase I samples to estimate the process mean had direct consequences on the performance of a two-sided CUSUM chart. It follows from Table 4 that the out-of-control ARL was relatively smaller than the desired. Hence, the effect of estimating the standard deviation from Phase I samples had less impact on the ARL performance of the CUSUM chart. However, the very large values of the accompanying SDRLs when was small required the availability of a large amount of Phase I samples. This was also the case when both the parameters were estimated (cf. Table 5). In all the three cases, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, the ARL and SDRL values were closer to the desired values in Table 2 as the number of Phase I observations, increased. Furthermore, parameter estimation had a more adverse impact on the performance of a two-sided CUSUM chart based on smaller reference value and designed for quick detection of very small changes in the process mean.

3.2. Effect of Estimation on Two-Sided CUSUM Control Limits

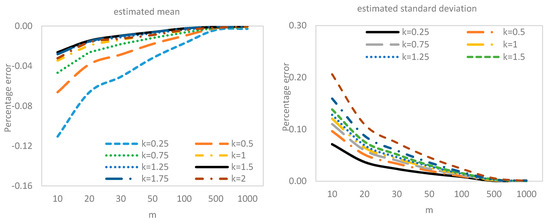

To study the effect of estimation error on the two-sided CUSUM control limits, we used a sample size of and set the in-control to . For each value of and , the corresponding value of the control limits were computed based on 100,000 iterations. Table 6 presents the two-sided CUSUM control limits using values of ranging from 10 to 1000. Once again, the use of a small number of Phase I observations to estimate the unknown in-control chart parameters give the control limit that is higher or lower than the desired value when the mean or the standard deviation is estimated, respectively. Similar to the ARL performance and the displayed percentage error curves in Figure 1, quite a larger number of Phase I samples was required to achieve the desired control limit. The problem, however, is the availability of such an amount of Phase I data in practical applications. Hence, the need to design a more robust scheme that can minimize the practitioner-to-practitioner variation, particularly when extreme values or outliers was involved.

Table 6.

Control limits for the two-sided CUSUM chart when the in-control mean and standard deviation are either known or estimated .

Figure 1.

Control limits for the two-sided CUSUM chart when the in-control mean and standard deviation are either known or estimated .

4. The Outliers and CUSUM Chart with Estimated Parameters

The effect of estimation errors on the performance of a CUSUM chart may further be strained if there exist some extreme values in the Phase I samples. Both the in-control and the out-of-control ARL and SDRL values will be different from those of the theoretical CUSUM charts. In this section, we evaluated the effects of the outliers on the performance of a two-sided CUSUM control chart with estimated parameters. Using a simulation approach, outliers were generated from the mixture distribution, where regular observations were from and the remaining observations came from a multiple of with degrees of freedom, [28]. That is, each observation was generated from a mixture distribution

where is the probability of having a multiple of added and is the outlier model multiplier. A value of indicates no presence of an outlier in the sampled data. Without loss of generality, we set and . The values of is set equal to 1, 2 or 3 corresponding to the small, medium and large outlier, respectively.

The mean and the variance of mixture distribution in Equation (10) are derived in Equations (11) and (12) respectively.

We set up a CUSUM chart using the same design parameters, and as in Section 3. he in-control ARL and SDRL values for the two-sided CUSUM chart based on this model with and are presented in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9. To save space, we restricted the study to in-control cases having seen the behavioral pattern for the out-of-control cases in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 7.

In-control average run length (ARL) and standard deviation run length (SDRL) values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of outlier when the in-control standard deviation is known, and mean is estimated .

Table 8.

In-control ARL and SDRL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of an outlier when the in-control mean is known, and the standard deviation is estimated .

Table 9.

In-control ARL and SDRL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of an outlier when the in-control mean and standard deviation are estimated .

From Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, it was observed that estimating , or both in the presence of outliers, to set up a CUSUM chart had a significant effect on the ARL and SDRL performance of the chart. Particularly, when the number of Phase I samples, was small. The in-control ARLs were approximately equal to the limiting value of 200 when . As expected, the RL values were directly proportional to and . That is, the in-control ARL and SDRL deteriorated with the increasing number of the false alarm rate as , or both the design parameters increased. In fact, the deterioration level became more alarming with the increase in an outlier metric multiplier, . Furthermore, as the number of Phase I samples increased, the ARL approached its theoretical value and much faster than its corresponding SDRL (cf. Table 7). However, this was not the case for Table 8 and Table 9, when . In general, increasing the number of Phase I data will reduce the occurrence of false alarm and bring the RL to be closer to the theoretical value. Unfortunately, this may not be visible in practice. Thus, we suggest a design structure based on the robust Tukey outlier detection model.

5. Performance of the Tukey CUSUM Control Chart

In this section, we studied the performance of the proposed Tukey model based CUSUM control chart with estimated parameters. Let denote Phase I samples and be the median samples. Then an observation from is declared as an outlier if , where is the interquartile range. and are the first and third quartile of , corresponding to the 25th and 75th percentile, respectively. The constant, is the confidence factor commonly chosen between 1.5 and 3.0. The confidence factor of Tukey’s detector is selected so that it is not too small leading to unnecessary screening of observations that are not outliers, and at the same time it should not be too large implying the inability of the detector to detect any outliers. For the said reason, is chosen to be for the current study (for more details on the Tukey’s outlier detector see, Tukey [28]).

Once an outlier is detected from the Phase I sample using Tukey’s model, it is screened and the remaining data points are used to estimate mean and variance of the process. After screening the suspected outliers, distribution of the remaining data points in Phase I is revised from a mixture distribution to a truncated mixture distribution. Here, the truncation limits are set to be and where and are lower and upper detection limits, respectively. Finally, the truncated mean and variance for the Phase I data points are defined, respectively, as follows:

where and . is the cumulative distribution function of . The truncated mean and variance in Equations (13) and (14) are evaluated for different values of and , and are given in Table 10.

Table 10.

Non-truncated and truncated mean and variance of mixture distribution of and .

Table 10 clearly indicates that mixing outliers in the distribution disturbs the mean and variance, especially for the larger values of . On contrary, when the distribution is truncated (i.e., Tukey’s outlier detector is applied) this disturbance in the mean and variance is negligible. In view of this discussion, the estimates of the process mean, and variance obtained from the truncated distribution (i.e., after screening the data using Tukey’s model) will have the minimal effect of outliers introduced in the Phase I samples.

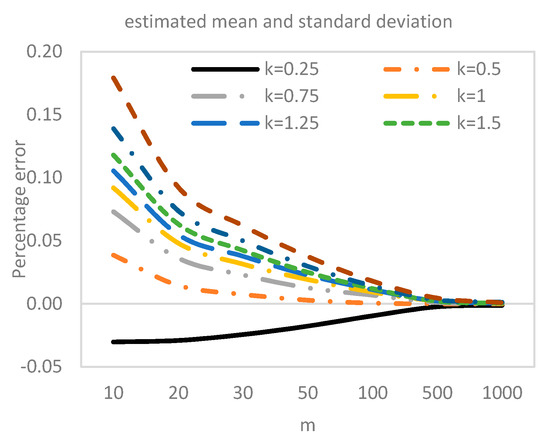

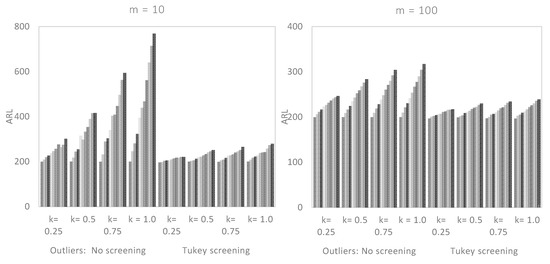

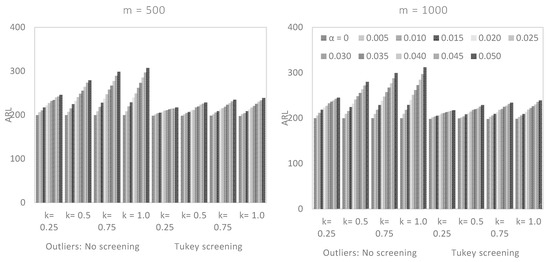

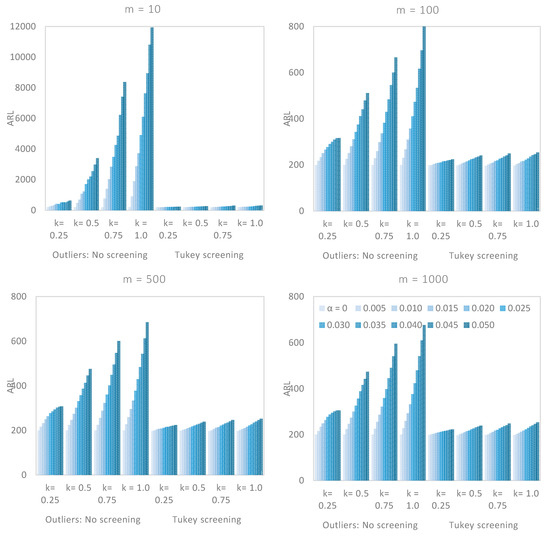

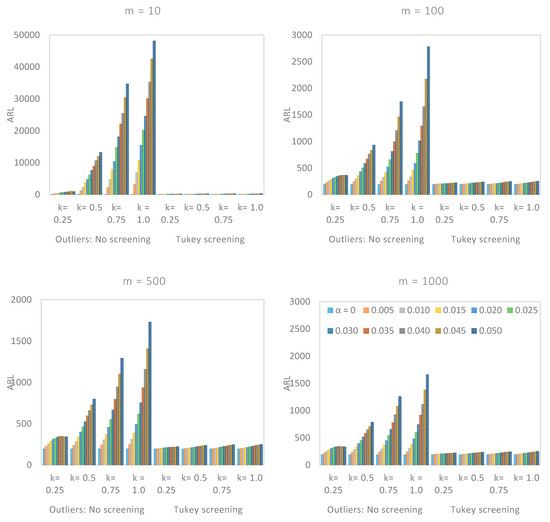

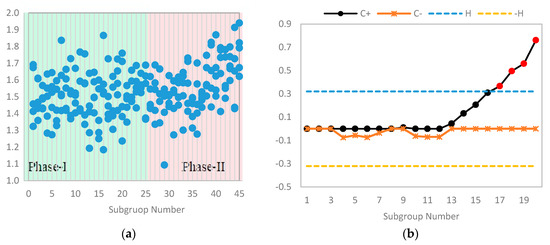

Using the same design structure and parameters as in Section 3 and Section 4, we computed the in-control ARL and SDRL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart based on the Tukey outlier detection model with the estimated parameters. Three cases were considered, when the mean, the standard deviation or both were estimated. To access the performance of the proposed charts, we present in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, a graphical display of the in-control ARL values with and when the magnitude of outlier multiplier is small (), medium () and large (). We presented only the case when both the mean and the standard deviation were estimated, as the other two cases had similar conclusions. Furthermore, we also showed the in-control ARL values in the presence of outliers without screening in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 for a quick comparison. With the two charts side-by-side, we outlined our findings under the following headings.

Figure 2.

In-control ARL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of an outlier, with and without screening, when the parameters are estimated .

Figure 3.

In-control ARL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of an outlier, with and without screening, when the parameters are estimated .

Figure 4.

In-control ARL values for the two-sided CUSUM control chart in the presence of an outlier, with and without screening, when the parameters are estimated .

5.1. Performance Comparison with Respect to m

We saw earlier that the number of Phase I data, , did have a significant effect on the performance of a CUSUM chart. From Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, we saw that there was a vast difference in the reported between non-screened data and when the robust Tukey outlier detection model was applied to construct a CUSUM chart, particularly when was small. For example, in Figure 3, if and , the for non-screened data were in five figures while the corresponding Tukey screened data were relatively closed to the target value. Even an increase in the number of Phase I observations with no screening did not appear to have a significant impact on the chart’s performance as the outlier multiplier increased. The Tukey screened counterpart, however, was getting closer to the limiting value , as increased.

In other words, the use of the Tukey outlier detector in the construction of a CUSUM chart would maintain the performance of the chart, even with the handful amount of Phase I data.

5.2. Performance Comparison with Respect to α

If , the in-control ARL values of CUSUM charts were approximately equal to the theoretical value of and indicates the absence of outliers in the Phase I sampled data. However, as the magnitude of increased, the non-screened data blew out of proportion, particularly when was small and . For example, if and , in Figure 2, the for the non-screened observations was 770 as against to 280 when the Tukey outlier detection model was applied. Even with the large values of and , the Tukey screened data appeared to be getting closer to the nominal value as increased. The same conclusion could not be made for non-screened data, as the in-control ARL values remained high when was relatively large (cf. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). This means that the Tukey’s model would not only keep the on target but also maintain the performance of the CUSUM control chart. In general, we observed that the effect of was minimal when was small.

5.3. Performance Comparison with Respect to w

The larger the magnitude of outlier multiplier , the worst the in-control ARL value of a two-sided CUSUM chart. If the outliers in a Phase I data were not screened, the was so huge as increased, that the capability of the CUSUM chart in process monitoring was seriously affected. Unlike the Tukey based chart that tried to maintain the at the target value. For example, if and , the in-control ARL values for the non-screened data were and 1025 when and , respectively. Compared to the screened Phase I data by the Tukey’s model with ARL values of 217, 222 and 225. Thus, the Tukey CUSUM chart could relatively withstand the impact of outlier multiplier as compared to the chart based on non-screened data.

6. Illustrative Example

For illustrating the application of Tukey’s outlier detectors with the CUSUM control chart, we used a dataset from [3]. The variable of interest was the flow width measurement (in microns) for the hard-brake process. The data consisted of twenty-five in-control Phase I samples and twenty out-of-control Phase II samples where the average width had increased due to an assignable cause(s). The process mean and standard deviation were estimated (cf. Equations (2)–(4)) from Phase I samples and were found to be and , respectively. These estimates were used to set up a CUSUM control chart for Phase II samples.

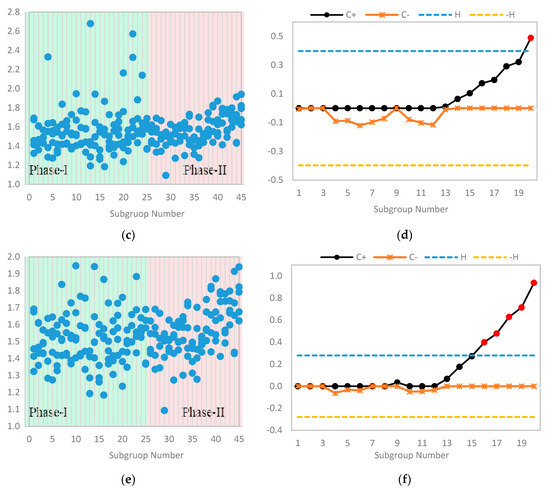

It is clearly observed from the scatter plot given in Figure 5a that the observations were relocated in Phase II. Further, it might also be confirmed from the CUSUM chart plotted in Figure 5b, which indicates several out-of-control signals in Phase-II. These findings led to the evidence that the hard-brake process had a positive shift at subgroup number fifteen and onwards.

Figure 5.

Scatter plots and the CUSUM control chart outputs for the dataset on the width of the hard-brake process.

Now using the data perturbation technique (cf. Kargupta, Datta [29] and Liu, Kargupta [30]), we introduced random outliers in different subgroups. Further, the process mean and standard deviation were estimated and found out to be and , respectively. Based on these estimates, we constructed the limits, which were further used to monitor the location of Phase II samples. In Figure 5c, the scatter plot depicts a slight upward change in Phase II, and control chart presented in Figure 5d shows that the out-of-control situation in Phase II was delayed (to subgroup number twenty) due to a small number of outliers present in Phase I. This happened because the limits widened due to the variation in Phase I estimates of process mean and standard deviation.

Finally, by using the above-mentioned contaminated Phase I data, we estimated the limit of the Tukey’s outlier detector, which was found to be . Now for any value, the absolute deviation from the median (i.e., ) greater than implies that the corresponding value is an outlier and needs to be screened from the data. Hence, by using the outlier detector, six observations were screened from the Phase I data. Further, the process mean and standard deviation were estimated and found out to be and , respectively. These new estimates were similar to the estimates of the original data and the scatter plot of the data is given in Figure 5e, which also showed upward trend in Phase II. In Figure 5f, the control chart is presented, which revealed that the there was no change in the limits, but the chart had detected an increase in the process mean at subgroup number sixteen.

7. Practical Application

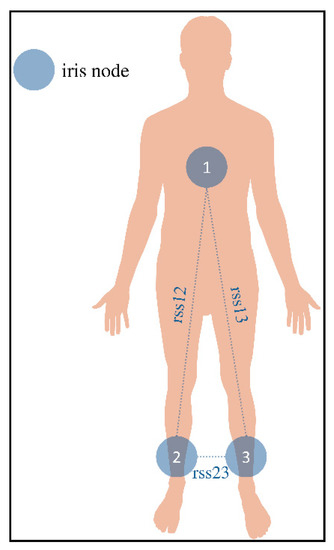

In recent years, activity recognition (AR) became an emerging research topic due to the advancement of electronic devices. AR is commonly used in pattern recognition, ubiquitous computing, human behavior modeling and human–machine interaction. In health care studies, different electronic devices are commonly used to recognize everyday life activities. In eldercare centers, these facilities provide assistance and care to the elders and help to ensure their safety and successful aging. Commonly, wearable devices and cameras are used to monitor everyday life activities, but these approaches suffer from several disadvantages such as intrusiveness, time-consuming processing and low resolution. Therefore, to overcome these challenges in real-time activity recognition, Hong, Kang [31] used an alternative method named as multisensor data fusion (assembly reliability evaluation method—AReM). For a more detailed introduction on the AReM see [32]. In the AReM system, information is gathered from an inertial sensor embedded in a smartphone and wireless sensor system, which is plugged between the user and environment. Further, in a wireless sensor network, the movement of an individual is measured in the received signal strength (RSS) between the user and environment. For the AR dataset [31], designed a competition. In which three IRIS motes are used and placed on the chest, the right and left ankle of an actor (cf. Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Placement of IRIS nodes on the actor’s body (cf. (Palumbo, Gallicchio [33]).

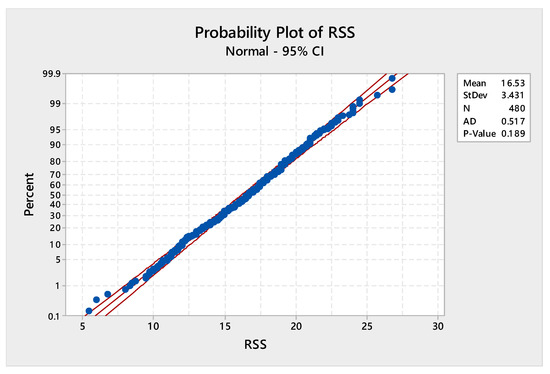

From this wireless sensor network, data was recorded on the actor’s activities such as; bending, cycling, standing, sitting, laying and walking. Further, for the first task of heterogeneous AReM, they considered activities such as cycling and standing. For the application purpose, we were concerned to detect a change in the pattern of RSS generated through the heterogeneous AReM setup. The AR time series dataset contained 480 observations in total, and each observation was obtained after 250 milliseconds. The average of RSS against the three IRIS motes (i.e., rss12, rss13, and rss23) was available in 15 different sequences of each activity. In our application, we considered the first sequence of the rss13 IRIS mote (chest-left ankle). The average of RSS of cycling was considered as in-control Phase I samples and average RSS of standing was considered as the out-of-control Phase II sample points. To access the normality of Phase I data set, we plotted a probability plot at the 95% confidence interval (cf. Figure 7) and also applied the Anderson–Darling test ( and ), which provided the evidence that the Phase I data set was normal.

Figure 7.

Probability plot of the received signal strength (RSS) values of the rss13 mote belonging to the cycling activity.

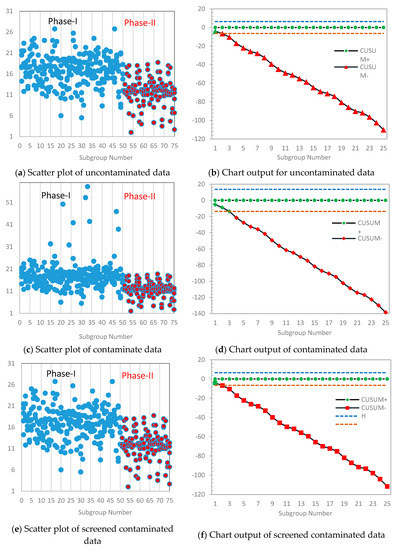

The RSS values of the chest-left ankle mote belonging to the cycling activity were clubbed into Phase I subgroups, and only the first 50 subgroups were used for the plotting purpose. Moreover, the first 25 subgroups based on the RSS values of chest-left ankle mote belonging to the standing activity were used as Phase II samples. The dataset of 75 subgroups is reported in Table 11. The process mean and standard deviation were estimated from the Phase I samples and found to be 16.9734 and 3.4764, respectively. These estimates were then used to construct the CUSUM chart for the Phase II samples. Figure 8a,b presents the scatter plot for the original data and the control chart output, respectively.

Table 11.

Phase-I subgroups of RSS values chest-left ankle mote. Phase-II subgroups of RSS values chest-left ankle mote.

Figure 8.

Scatter plots and CUSUM control chart outputs for the dataset on the received signal strength process.

It was evident from Figure 8a that there was a downward relocation in Phase II samples, a point equally supported by the corresponding CUSUM chart, which gave an out-of-control signal right from the start of the plots in Figure 8b. Now to access the effect of the outliers, we followed the same procedure as described in Section 6, by first contaminating the Phase I data and used the estimates obtained, and to setup a CUSUM control chart for the Phase II data (cf. Figure 8c,d). Secondly, we used the Tukey outlier detector to screen the Phase I samples, computed the control chart parameters and used the estimates, and to construct the CUSUM chart for the Phase II samples (cf. Figure 8e,f).

The introduction of outliers in the Phase I samples, Figure 8c gave rise to wider control limits, which in turn delayed the out-of-control signal in the Phase II control chart setup (cf. Figure 8d). However, the application of the outlier detector on the contaminated Phase I data resulted in the screening out of about ten data points (cf. Figure 8e). Subsequently, the corresponding CUSUM chart in Figure 8f shows a similar behavioral pattern as those of the original data in Figure 8b.

8. Conclusions

In this article, we evaluated the in-control performance of a two-sided CUSUM control chart when the parameters were estimated in the presence of outliers based on the robust Tukey detection model. Using a Monte Carlo simulation approach, the ARL and SDRL were computed for a different number of Phase I data.

The results show that a large number of Phase I data was required to minimize the practitioner-to-practitioner variability. In the presence of outliers, a larger amount of Phase I data was needed, which might not be realistic in practical applications. The results further revealed that the use of the Tukey outlier detector in the construction of a two-sided CUSUM control chart required fewer Phase I observations to stabilize the chart’s performance. Therefore, it was plausible to use the Tukey’s model in the design structure of a CUSUM chart when the parameters were estimated for efficient process monitoring, particularly when the observations were prone to outliers. The advantage of this proposal is its simplicity to design and it is easy to use. A point demonstrated by the illustrative and application examples of the new Tukey CUSUM control chart. The scope of this study might be extended to other control charts design strategies like the Shewhart and exponentially weighted moving average.

Author Contributions

Study planning, mathematical derivations, calculation of results and draft writing was done by authors N.A. and M.R.A. under the supervision of author M.R. Application of proposed model on real-life dataset was done and written by author T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, under grant number IN171010.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CUSUM | Cumulative Sum |

| ARL | Average Run Length |

| SDRL | Standard Deviation of Run Length |

| RSS | Received Signal Strength |

| RL | Run Length |

| AR | Activity Recognition |

| AReM | Assembly Reliability Evaluation Method |

References

- Abujiya, M.a.R.; Riaz, M.; Lee, M.H. Enhanced cumulative sum charts for monitoring process dispersion. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, E.S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 1954, 41, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, N.A.; Zwetsloot, I.M.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Woodall, W.H. CUSUM charts with controlled conditional performance under estimated parameters. Qual. Eng. 2016, 28, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonhoven, M.; Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Does, R.J. Robust location estimators for the X-bar control chart. J. Qual. Technol. 2011, 48, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Does, R.J.M.M.; Abbas, N. Robust CUSUM control charting. Qual. Eng. 2013, 25, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdouni, A.; Castagliola, P.; Taleb, H.; Celano, G. A variable sampling interval Shewhart control chart for monitoring the coefficient of variation in short production runs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 5521–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Lin, Z. Investigating the Impact of Ranked Set Sampling in Nonparametric CUSUM Control Charts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2017, 33, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Wang, Z. A new exponentially weighted moving average control chart for monitoring the coefficient of variation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 78, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Nazir, H.Z.; Abbas, N.; Riaz, M.; Ali, A. Performance evaluation of joint monitoring control charts. Sci. Iran. 2017, 24, 2152–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hawkins, D.M. Identification of Outliers; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1980; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, R.J.; Cook, R.D. Outlier … s. Technometrics 1983, 25, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, V.; Lewis, T. Outliers in Statistical Data, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs, F.E. Procedures for Detecting Outlying Observations in Samples. Technometrics 1969, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietjen, G.L.; Moore, R.H. Some Grubbs-Type Statistics for the Detection of Several Outliers. Technometrics 1972, 14, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.J.; Khoo, M.B.; Teoh, W.L.; Haq, A. Run sum chart for monitoring multivariate coefficient of variation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 109, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W.L.; Khoo, M.B.; Castagliola, P.; Yeong, W.C.; Teh, S.Y. Run-sum control charts for monitoring the coefficient of variation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 257, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, E.M.; Ng, R.T.; Tucakov, V. Distance-based outliers: Algorithms and applications. VLDB J. 2000, 8, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Y.K.; Balasooriya, U. Tests for Multiple Outliers in an Exponential Sample. Indian J. Stat. Ser. B (1960–2002) 1991, 53, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, M.; Dierckx, G.; Vanpaemel, D. Detecting influential data points for the Hill estimator in Pareto-type distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2013, 65, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagliola, P.; Amdouni, A.; Taleb, H.; Celano, G. One-sided Shewhart-type charts for monitoring the coefficient of variation in short production runs. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2015, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. The Mean and Standard Deviation of the Run Length Distribution of X Charts when Control Limits are Estimated. Stat. Sin. 1997, 7, 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Henderson, G.R.; Epprecht, E.K.; Woodall, W.H. Estimating the Standard Deviation in Quality-Control Applications. J. Qual. Technol. 2010, 42, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, H.Z.; Abbas, N.; Riaz, M.; Does, R.J.M.M. A comparative study of memory-type control charts under normal and contaminated normal environments. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2016, 32, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Xie, M. Models and monitoring of zero-inflated processes: The past and current trends. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2019, 35, 2540–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Champ, C.W.; Rigdon, S.E. The Run Length Distribution of the CUSUM with Estimated Parameters. J. Qual. Technol. 2004, 36, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, M.X. Analysis and Design of One-And Two-Sided CUSUM Charts with Known and Estimated Parameters. Master’s Thesis, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kargupta, H.; Datta, S.; Wang, Q.; Sivakumar, K. Random-data Perturbation Techniques and Privacy-Preserving Data Mining. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2005, 7, 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Kargupta, H.; Ryan, J. Random Projection-based Multiplicative Data Perturbation for Privacy Preserving Distributed Data Mining. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2006, 18, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, E.P.; Kang, H.W.; Kang, C.W. DEWMA control chart for the coefficient of variation. In Proceedings of the Advanced Materials Research, Qinhuangdao, China, 28–31 October 2011; pp. 1682–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Du Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Tran, K.P.; Ho, D.P. On the performance of VSI Shewhart control chart for monitoring the coefficient of variation in the presence of measurement errors. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.; Gallicchio, C.; Pucci, R.; Micheli, A. Human Activity Recognition Using Multisensor Data Fusion Based on Reservoir Computing. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2016, 8, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).