Abstract

The diagnosability is an essential subject for the reliability of a multiple CPU system. As a celebrated topology structure of interconnection networks, an n-dimensional wheel network has numerous great features. In this paper, we discuss the diagnosability of with missing edges under the comparison model. Both the local diagnosability and the strong local diagnosability feature are studied; this feature depicts the equivalence of the local diagnosability of a node and its degree. We demonstrate that possesses this feature, containing the strong feature even with up to missing edges in it, and the outcome is ideal regarding the amount of missing edges.

1. Introduction

Numerous multiple CPU systems have interconnection networks (networks for short) as fundamental topologies, and a network is normally spoken to by a graph where nodes speak to CPUs and links speak to communication links between CPUs. For a system, a few CPUs may fizzle in the system, so CPU flaw distinguishing proof assumes a significant job for solid figuring. The distinguishing process is known as the diagnosis of the system. A system is supposed to be t-diagnosable if all broken CPUs can be distinguished without substitution, given that the quantity of faults presented does not surpass t. The diagnosability of a system G is the largest amount of t such that G is t-diagnosable [1,2,3].

A few diagnosis models (e.g., PMC model [4], BGM model [5] and MM model [6]) are suggested to examine the ability to be diagnosed. Under the PMC model [4], the diagnosis of a system G is achieved through two adjacent nodes in G testing each other. The BGM model [5] uses the same testing strategy as the PMC model, but it assumes that a faulty unit is always tested as faulty regardless of the state of the tester. Specifically, the MM model, is notable and broadly utilized. In the MM model, likewise named the comparison model, to diagnose a system, a node sends the similar assignment to two of its neighbors, and afterward looks at their responses. Sengupta and Dahbura [1] suggested an uncommon instance of the MM model, named the MM model, in which every node can test its any couple of adjacent nodes. These were investigated within the PMC model and MM model or MM model. Fan [2] studied the diagnosability of crossed cubes under the comparison diagnosis model. Lai et al. [3] discussed the conditional diagnosability measures for large multiprocessor systems under the PMC model. Chang et al. [7] studied the structural properties and conditional diagnosability of star graphs by using the PMC model. Feng et al. [8] gave the nature diagnosability of wheel graph networks under the PMC model and MM model. Lin et al. [9] investigated the conditional diagnosability of Cayley graphs generated by transposition trees under the comparison diagnosis model. Peng et al. [10] gave the g-good-neighbor conditional diagnosability of hypercube under PMC model. Wang et al. [11] studied the 1-good-neighbor diagnosability of Cayley graphs generated by transposition trees under the PMC model and MM model. Wang et al. [12] gave the 1-good-neighbor connectivity and diagnosability of Cayley graphs generated by complete graphs under the PMC model and MM model. Yuan et al. [13] obtained the g-good-neighbor conditional diagnosability of k-ary n-cubes under the PMC model and MM model.

Hsu and Tan [14] observed that in case we only consider the global faulty or fault-free status in a t-diagnosable system, at that point we lose some local subtleties of the system. Therefore, Hsu and Tan [14] suggested a measure of the ability to be diagnosed for a multiple CPU system G, which is the local diagnosability of G. This measure considers the local diagnosability of each CPU rather than the entire system. Chiang and Tan [15] suggested a helpful local structure named an extended star to ensure the node diagnosability and a sufficient condition to decide the local diagnosability under the MM model. They found that there is a solid connection between the local diagnosability of G and the classical diagnosability of G. The system G has the strong local diagnosability feature (property) if the local diagnosability of each node is equivalent to its degree in G. Following this idea, the strong local diagnosability has been generally investigated. Chiang et al. [16] found that an n-dimensional star has the strong local diagnosability even with up to missing edges. Furthermore, Cheng et al. [17] obtained the strong local diagnosability to -star graphs and the Cayley Graphs produced by 2-trees. In 2018, Wang and Ma [18] demonstrated that an n-alternating group graph possesses the strong local diagnosability feature even with up to missing edges in it under the MM model. Wang et al. [19] showed that an n-dimensional bubble-sort star graph has the feature even with up to missing edges, under the MM model. Here, we present that an n-dimensional wheel network has the local diagnosability feature even with up to missing edges in it under the MM model, and the consequence is optimal respect to the number of missing edges.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Definitions and Presentations

A multiple CPU system is presented as a directionless graph , whose vertices (nodes) determine CPUs and edges (links) determine communication links. Given a nonempty node subset of V, the induced subgraph by in G, denoted by , is a graph, whose node set is and the link set is the set of each link of G with both endpoints in . The degree of a node v is the amount of links incident with v. We denote by the minimum degrees of nodes of G. We describe the neighborhood of a node v in G as set of nodes adjacent to v. u is named a neighbor or a neighbor node of v for . Let . We use to represent the set . For neighborhoods and degrees, we shall typically neglect the subscript for the graph once no misperception ascends. A graph G is k-regular if for all , . The connectivity of a connected graph G is the minimum number of nodes whose exclusion effects in a disconnected graph or just a node left when G is complete. The edge-connectivity of G is the minimum number of links whose exclusion outcomes in a disconnected graph. A graph is bipartite if its node set can be partitioned into two subsets X and Y its fragments such that and has no link. The girth is the length of the shortest cycle in a graph G. The automorphism group of a graph G is transitive if there is an automorphism to arbitrary couples of nodes in G such that . Here, G is named node transitive. For graph-related vocabulary and representation not described we refer the reader to [20].

Proposition 1

([20]). For a graph , .

2.2. The MM Model

The MM model is originally suggested by Malek and Maeng in [6]. In the MM model, the diagnosis is performed by transmitting the same testing errand to a couple of CPUs and looking at their responses. Within the MM model, we generally accept the yield of a comparison achieved by a defective CPU is questionable. The comparison scheme of a system is presented as a multi-graph, denoted by , where L is the labeled-link set. A labeled link determines an evaluation where two vertices u and v are compared by a node w, which indicates . The collection of each comparison outcome in is named the syndrome of the diagnosis, denoted by . If the comparison differs, then , else, . Thereat, a syndrome is a mapping from L to . Sengupta and Dahbura [21] suggested MM model. The MM model is a specific type of the MM model. Within the MM model, each comparison of G is in the comparison system of G, i.e., if , then . The set of each defective CPU in the system is named a faulty set. It can be an arbitrary subset of . For a given a syndrome . Then a subset of nodes is supposed to be consistent with if can be formed from the state, for all such that , if and only if at least one of is in F. Let signify the set of each syndrome that F is consistent with. Let and be two different sets in . If , it is said and be a distinguishable pair (couple); else, is an indistinguishable pair (couple).

The primary merit of the MM model is its simplicity in identifying a faulty CPU because the comparison of pairs of CPUs seems to be easier than testing one CPU by another or others [22]. The MM model has two advantages in fault identification: the MM model requires no additional hardware; transient and permanent faults may be identified before the comparison program has completed [22]. Sengupta et al. [21] investigated many significant features of a diagnosable system using the MM model. The MM model might result in the development of a polynomial-time diagnosis algorithm in general MM self-diagnosable systems, and complexity leads to determining the diagnosability level of systems [23].

2.3. Wheel Networks

The wheel networks [24] are a famous topology construction in interconnection networks. We consider this topology in this section.

Let Q be a finite group, and assume S be a spanning set of Q such that S does not contain the identity element. The directed Cayley graph is described as follows: its node set is Q, its arc set is . If for each , , then all of arc sets of have parallel links going in diverse directions. If we replace two arcs of the parallel link going in different directions in with a link, then we get a directionless graph named the undirected Cayley graph. Each Cayley graph in this paper is an undirected Cayley graph.

In the permutation , . For convenience, we signify the permutation by . Each permutation is denoted by a product of cycles [25]. For instance, . Specially, . The product of two permutations is the composition function trailed by , i.e., . For algebraic terminology and notation not described here we refer to [25].

Let , and consider H as a simple connected graph whose node set is . Each link of H is reflected as the transposition in symmetric group , and so the link set of H corresponds to a transposition set S in . Therefore, H is named a transposition simple graph. The Cayley graph Cay, denoted by Cay, is named the corresponding Cayley graph of H. As mentioned in [26], . Once H is a tree (resp. path, star) of n nodes, the corresponding Cayley graph is named an n-dimensional transposition tree (resp. bubble-sort graph, star graph), and denoted by (resp. , ) [26].

Proposition 2

([27]). is -regular for .

Proposition 3

([28]). for .

Once H is a sector of nodes, i.e., and , the corresponding Cayley graph is named an n-dimensional bubble-sort star graph [27], denoted by . Once H is a wheel of nodes, i.e., and , the corresponding Cayley graph is named an n-dimensional wheel network [24], denoted by . In fact, an n-dimensional wheel network is the graph with node set = in which 2 nodes u, v are adjacent if and only if , , or , , or .

As can be seen in [27,29], the bubble-sort star graph possesses lesser diameter than , equal diameter to , and larger connectivity than and , and the ability to be embedded of the bubble-sort star graph is far superior to that of the star graph. Consequently, utilizes the benefits of and , and overcomes their own limitations. Note that the diameters of and are both equal to for [27,30], and the can be embedded into a , outperforms in connectivity [8,28]. Consequently, the wheel network is the popular and multipurpose net system for multiple CPU systems.

Notice that is a special Cayley graph. This graph possesses some features.

Proposition 4

([31]). For each integer , is -regular and node transitive.

Proposition 5

([31]). For each integer , is bipartite.

Proposition 6

([8]). For each integer , the girth of is 4.

can be partitioned into n disjoint subgraphs , where each node takes a fixed integer i in the last place for . Obviously, is isomorphic to , where is an -dimensional bubble-sort star graph. Let , then and are named outside neighbors of v. A link is named a cross-edge concerning the given factorization if its two nodes are in different ’s.

3. The Local Diagnosability

Let and be two different subsets of V for a system , and let the symmetric difference .

Definition 1

([4]). A system G is t-diagnosable if all the faulty processors can be precisely pointed out given that the number of faulty processors is at most t.

Lemma 1

([21]). A system is t-diagnosable if and only if, for every couple of different set of nodes with and , is a distinguishable pair.

Lemma 2

([21]). Let and be two different subsets of nodes. is a distinguishable couple if and only if at least one of the next situations is fulfilled:

- (1)

- and such that .

- (2)

- and such that , or

- (3)

- and such that .

Opposite to the global sense in system diagnosis, Chiang and Tan [15] determined a local idea, named the local diagnosability of an assumed node in a system. This technique needs only the precise identification of the defective or defective-free position of a single node. The concept of local diagnosability is presented.

Definition 2

([14]). A system is locally t-diagnosable at a node x if, assumed a test syndrome given by the system within the presence of a set of faulty vertices F comprising of x with , each set of faulty nodes is consistent with and , must also contain node x.

An equivalent method of declaring the overhead description is specified here.

Definition 3

([14]). A system is locally t-diagnosable at a node x for every different couple of faulty subsets and of V with and if , and and is distinguishable.

The local diagnosability of an assumed node in given here:

Definition 4

([14]). The local diagnosability of a node x in a system is described as the maximum number of t for G that is locally t-diagnosable at x, i.e., Gt.

The notion of a system that is t-diagnosable at a node is consistent with the classical notion of a system that is t-diagnosable in a global sense. The connection between those two is as follows:

Lemma 3

([14]). A system is t-diagnosable if and only if G is locally t-diagnosable at each node of G.

Lemma 4

([14]). The diagnosability of a system is equivalent to the minimum value within the local diagnosability of each node in G, i.e., .

From Lemma 4, we can identify the diagnosability of a system by figuring the local diagnosability of every node. The diagnosability of many famous networks which are node-symmetric can be identified using the effective measure. To assure the local diagnosability of a node x, an extended star structure at the node x is suggested as given next:

Definition 5

([15]). Fix a node x in a graph and a positive integer . An extended star in x of degree p is a subgraph of G with the node set , and the link set .

Here, x is named the root of . An extended star is an important structure in figuring the local diagnosability of a given node. The time complexity of the algorithm to diagnose a given CPU is bounded by and that to diagnose all the faulty CPUs in a system with N CPUs is bounded under the comparison model, provided there is an extended star structure at each CPU and that the time for looking up the testing result of a comparator in the syndrome table is constant, where N is the total number of CPUs [15].

Lemma 5

([15]). Let x be a node in a graph with . The local diagnosability of x is p if there is an extended star in G at x.

Notice that the local diagnosability of a node x may or may not be equal to its degree. So two concepts are suggested as follows:

Definition 6

([14]). Let x be a node within a graph . The node x has the strong local diagnosability feature if the local diagnosability of x is equivalent to its degree in G, i.e., .

Definition 7

([14]). Let be a graph. G contains the strong local diagnosability feature if each node in G possesses the strong local diagnosability feature.

The diagnosability of a system may be derived straightforwardly.

4. The Diagnosability of Wheel Networks

Lemma 6

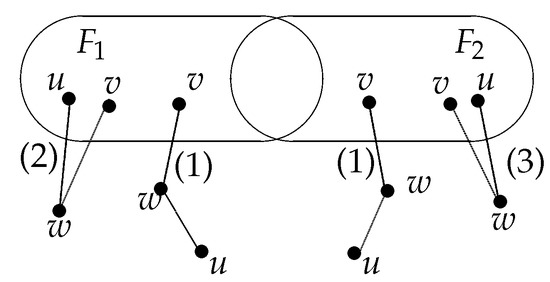

([21]). Under the MM* model, a system is t-diagnosable at a node x if and only if for all different couples of faulty subsets and of V with and , and , satisfies one of the next conditions:

- (1)

- There exist two nodes and 1 node such that and ;

- (2)

- There exist two nodes and there exists 1 node such that and ;

- (3)

- There exist two nodes and there exists a node such that and (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustration of a distinguishable pair under the MM* model.

Figure 1. Illustration of a distinguishable pair under the MM* model.

Lemma 7

([19]). For every node x in the bubble-sort graph with , there is an extended star in at x.

Lemma 8.

For every node x in the wheel network with , there is an extended star in at x.

Proof.

We may partition into n disjoint subgraphs , where each node possesses a fixed integer i in the last position for . Obviously, is isomorphic to , where is an -dimensional bubble-sort star graph.

We will determine an extended star as a subgraph of at a given node x. By Proposition 4, is node transitive. Therefore, can be chosen as the root of , i.e., , where is the identity element of the symmetric group . By Lemma 7, for the bubble-sort graph with , there is an extended star in at x. So there is an extended star in at x. Note that has three outside neighbor nodes and , where and . Notice that the 3-path is in , and the 3-path is in , and the 3-path is in . We connected and to x, and then combine them with . Thus, we can obtain an extended star in at , i.e., an extended star exists in at x. □

Theorem 1.

Let be an n-dimensional wheel network with . Then the diagnosability of is , i.e., and possesses the strong local diagnosability feature.

Proof.

By Lemmas 5 and 8, the local diagnosability of every node x of is . By Lemma 4, the diagnosability of is , i.e., . Since the degree of every node x of is , the local diagnosability of every node is equivalent to its degree in . By Lemma 7, has the strong local diagnosability feature. □

Sometimes, many links in a multiple CPU system may be missing. A missing edge implies that a link between 2 CPUs that was faulty. The existence of missing edges in a system may affect the diagnosability of the whole system, and degrees and the local diagnosability of some nodes. Especially, in a regular graph, nodes that are adjacent to missing edges have lower degrees than others. Hence, those nodes may not keep the strong local diagnosability feature, and the graph may not keep the strong local diagnosability feature again. Those new degrees can be used to determine whether the incomplete graph keeps the strong local diagnosability feature or not. Next, we demonstrate that an n-dimensional wheel network keeps the strong local diagnosability feature even with up to missing edges.

Lemma 9

([19]). Let be the bubble-sort graph with , and let be an arbitrary set of missing edges with . Thus possesses the strong local diagnosability feature for every node x in with missing edges , and outcome is ideal, respectful to the number of missing edges.

Lemma 10.

Let be an arbitrary set of missing edges with . For every node x in , there is an extended star at x.

Proof.

By Proposition 4, is node transitive. Therefore, can be chosen as the root of an extended star , i.e., , where is the identity element of the symmetric group . can be partitioned into n disjoint subgraphs , where each node has a fixed integer i in the last position for . Clearly, is isomorphic to , where is the bubble-sort star graph with the dimension .

Let for , and , then . For convenience, let , and denote , and three outside neighbors of . To prove this lemma, we need to discuss whether is an empty set or not. When , the first step is to discover an extended star in ; the second step is to find a 3-path in , a 3-path in and a 3-path in ; the third step is to connect , and to x. Then, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). For the case of , we obtain an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any 4-path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

It should be noted that removing a 4-path P from a graph G means removing all nodes and links of the 4-path except y from a graph G in this paper, where y is the only common node of P and G.

Firstly, we give two claims as follows.

Claim 1.

If , then there exists an extended star in at for . In the extended star , there exist at least and at most 4-paths (resp. 3-paths) with just common node .

Proof.

Notice that each is isomorphic to and , by Lemma 9, then there exists an extended star in at for and . Therefore, , and we can find at least and at most 4-paths (resp. 3-paths) with just common node in the combining the definition of the extended star. In particular, in the extended star , there exist just 4-paths (resp. 3-paths) with just common node if and only if each of edges in is incident with . □

Claim 2.

If , then there exists at least a 3-path in starting at for .

Proof.

By Propositions 1–3, we have that . Since each is isomorphic to , we have that . If , then is connected. By Proposition 6 and for . So a 3-path starting at can be found in for . □

Then we can find the extended star by discussing and as follows.

Case 1. .

By Claim 1, there exists an extended star in at x.

Case 1.1. .

Here, for . By Claim 2, there exists a 3-path (resp. , ) in (resp. , ). We connect , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any 4-path that contains any edge of and starts at x from B.

Case 1.2. .

If each of , and is less than , then we can complete the proof as Case 1.1. Clearly, at most one of , and is equal to , without loss of generality, we consider . Then . We choose a 4-path . Clearly, is in . By Claim 1 and , there exist 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. ). Notice that , and for , so there exists a 3-path starting at v in such that and have no common node. We can choose a 3-path starting at w in . Notice that any two of and have no common node, and each of and does not contain a missing edge. We connect , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 1.3. .

If each of , and is less than , then we can complete the proof as Case 1.1. Clearly, at most one of , and is equal to or . Without loss of generality, let , or . If , then the proof for can be completed as Case 1.2. If , then .

Case 1.3.1. .

Without loss of generality, let . Here, . We choose a 4-path . Clearly, is in . Combining Claim 1, there exist at least 3-paths in (resp. ). Notice that , and for , so there exists a 3-path starting at w in such that and have no common node. Choose a 3-path starting at v in . Notice that any two of and have no common node, and each of and does not contain a missing edge. We connect , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 1.3.2. .

Notice that . If , then we choose a 4-path . Clearly, is in . By Claim 1 and , there exist at least 3-paths in (resp. ). Notice that , and for , so there exists a 3-path starting at w in such that and have no common node. Choose a 3-path starting at v in . Notice that any two of and have no common node, and each of and does not contain a missing edge. We connect , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B), and B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any 4-path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

Case 2. .

Here, . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let f be an arbitrary link of , and let . Then , there exists an extended star in by Claim 1. Let .

Case 2.1. .

Here, is one of extended star at x of . Notice that , so we can connect , and to x. Combining them with , an extended star can be obtained in .

Case 2.2. .

Let be a 4-path containing f and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing from , denoted by A.

Case 2.2.1. f is incident with x.

Notice that , so we connect , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star can be obtained in .

Case 2.2.2. f is not incident with x.

Let be a 3-path containing f and starting at a, and then a is adjacent to x. Next, we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . Notice that , we can choose a 2-path that does not contain a missing edge in , where . By Claim 1 and , we can find 3-paths in , where . Note that, and for , so we can find a 3-path in that does not contain a missing edge, and and have no common node. At the same time, we can find a 3-path (resp. ) in (resp. ), and connect to a to obtain a 3-path . Notice that each of , , and do not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. We connect , , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star can be got in . The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 3. .

Notice that . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let f be an arbitrary edge of , and let . Then . Combining Claim 1, there exists an extended star in . Let .

Case 3.1. .

Here, is one of extended star at x in . We connect , and to x. Combining them with , an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any edge of and starts at x from B.

Case 3.2. .

Let be a 4-path containing f and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing from , denoted by A.

Case 3.2.1. f is incident with x.

Connect , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any edge of and starts at x from B.

Case 3.2.2. f is not incident with x.

Let be a 3-path starting at a, and let it contain f, then a is adjacent to x.

Case 3.2.2.1. .

Here, . Without loss of generality, let . Now we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . We can choose a 2-path in , where . Notice that , so does not contain a missing edge. By Claim 1 and for , we can find 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in , and any two of these 3-paths have no common node except u (resp. v, w). Notice that , and for , so we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node. We can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. We can connect to a to obtain . Notice that each of , , and does not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. We connect , , , to x. Combining them with A, an extended star can be got in . The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 3.2.2.2. .

Here, . Now we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . We can find in and in , where and . Since , we can choose a 2-path from and that does not contain a missing edge. Notice that and are in different ’s and , and we can connect to a to obtain a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge. By Claim 1 and for , we can find 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in , and any two of these 3-paths have no common node except u (resp. v, w). Notice that , and for . If , then we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. If , then we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. We connect , , , to x. Notice that each of , , and does not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B. The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 4. .

Here, . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let f be an arbitrary link of , and let . Then , so there exists an extended star in by Claim 1. Let .

Case 4.1. .

Here, is one of extended star at x in . We connect , and to x. Combining them with , an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

Case 4.2. .

Let be a 4-path containing f and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing from , denoted by A.

Case 4.2.1. f is incident with x.

Connect , and to x. Combining them with A, Then, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

Case 4.2.2. f is not incident with x.

Let be a 3-path starting at a and containing f, then a is adjacent to x.

Case 4.2.2.1. .

Here, .

Case 4.2.2.1.1. for some .

Without loss of generality, let . We can complete the proof as Case 3.2.2.1.

Case 4.2.2.1.2. and for some , .

Without loss of generality, let and . Now we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . We can choose a 2-path in , where . Notice that , so does not contain a missing edge. By Claim 1 and for , we can find 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in , and any two of these 3-paths have no common node except u (resp. v, w). Notice that , and for , so we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node. We can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ). Connect to a to obtain a 3-path . Notice that each of , , and does not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. We connect , , , to x. Combining them with A, we can get the extended star in . The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 4.2.2.2. .

Here, . Without loss of generality, let . Next, we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . We can find in and in , where and . Since , and do not contain a missing edge. We can choose a 2-path from and . Since and are in different ’s and , connect to a to obtain a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge. By Claim 1 and for , we can find 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in , and any two of these 3-paths have no common node except u (resp. v, w). Notice that , and for . If , then we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. If , then we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in , and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. We connect , , , to x. Notice that each of , , and does not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any edge of and starts at x from B. The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 4.2.2.3. .

Here, . Now we consider for . Without loss of generality, let . We can find in , in and in , where , and . Since , then , and do not contain a missing edge. Notice that , and are in different ’s and , then we can choose a 2-path from , and , and attach the 2-path to a to obtain a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge. By Claim 1 and for , we can find 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in , and any two of these 3-paths have no common node except u (resp. v, w). Notice that , and for . If , then we can find a 3-path that does not contain a missing edge in such that and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. If , then we can find a 3-path in that does not contain a missing edge, and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ) as well. If , then we can find a 3-path in that does not contain a missing edge, and and have no common node, and we can find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ). Notice that each of , , and does not contain a missing edge, and any two of them have no common node. We connect , , , to x. Combining them with A, an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B. The case of for can be proved similarly.

Case 5. .

Here, . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let be any two elements of and . Then , so there exists an extended star in by Claim 1. Let .

Case 5.1. Neither f nor belongs to .

Here, is one of extended star at x in . Notice that , so we connect , and to x. Combining them with , we can get an extended star in .

Case 5.2. contains f or .

Without loss of generality, we assume that contains only f. Let be a 4-path containing f and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing from , denoted by A. Next we discuss whether f is incident with x or not. If f is incident with x, then it can be proved as Case 2.2.1. If f is not incident with x, then it can be proved as Case 2.2.2.

Case 5.3. contains f and .

Case 5.3.1. f and are both incident with x.

Let (resp. ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing and from , denoted by A. Notice that , so we connect , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 5.3.2. Just one of f and is incident with x.

Without loss of generality, assumes that only is incident with x. Let (resp. ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing and from , denoted by A. Let be a 3-path containing f and starting at a, and then a is adjacent to x. The next proof can be completed as Case 2.2.2.

Case 5.3.3. Neither f nor is incident with x.

Next we discuss whether f and belong to the same path or not.

Case 5.3.3.1. f and belong to the same path in .

Then we can complete the proof as Case 2.2.2.

Case 5.3.3.2. f and belong to different paths in .

Let (resp. ) be a 3-path starting at a (resp. b), and it contains f (resp. ). Then a and b are both incident with x. Notice that . It is easy to find a 3-path (resp. ) that does not contain a missing edge in (resp. ), and (resp. ) and (resp. ) have no common vertices. Connecting (resp. ) to a (resp. b), we can obtain a 3-path (resp. ). Notice that , so we connect , , , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 6. .

Here, . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let be any two elements of and . Then , there exists an extended star in by Claim 1. Let .

Case 6.1. Neither f nor belongs to .

Here, is one of extended star at x in . Connect , and to x. Combining them with , an extended star is found in at x, (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

Case 6.2. contains f or .

Without loss of generality, we suppose that contains only f. Let be a 4-path containing f and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing from , denoted by A. Next we consider whether f is incident with x or not. If f is incident with x, then the next proof can be completed as Case 3.2.1. If f is not incident with x, then the next proof can be completed as Case 3.2.2.

Case 6.3. contains f and .

Case 6.3.1. f and are both incident with x.

Let (resp. ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing and from , denoted by A. Connect , and to x. Combining them with A, an extended star at x is found in , (with written simply as B). Notice that . If , then B satisfies the lemma. If , then we find an extended star to satisfy the lemma by removing any path that contains any link of and starts at x from B.

Case 6.3.2. Just one of f and is incident with x.

Without loss of generality, assume that only is incident with x. Let (resp. ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing and from , denoted by A. Let be a 3-path containing f and starting at a, and then a is adjacent to x. We can complete the proof as in Case 3.2.2.

Case 6.3.3. Neither f nor is incident with x.

Then we consider whether f and belong to the same path or not.

Case 6.3.3.1. f and belong to the same path in .

Then we can complete the proof as in Case 3.2.2.

Case 6.3.3.2. f and belong to different paths in .

Let (resp. ) be a 3-path starting at a (resp. b), and it contains f (resp. ). Then a and b are both incident with x. Notice that , then . Note that , . There is a 2-path (resp. ) that do not contain a missing edge in , or or , and the edge (resp. ), where (resp. ) is an outside neighbor of a (resp. b). Connecting (resp. ) to a (resp. b), we can obtain a 3-path (resp. ). Connect , , , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 7. .

Here, . By Claim 1, we can choose a 3-path (resp. , ) from at least 3-paths that do not contain a missing edge in (resp. , ). Let be any three elements of and . Then , by Claim 1, there exists an extended star in . Let .

Case 7.1. None of f, and belongs to .

We can complete the proof as in Case 5.1.

Case 7.2. contains just one of f, and .

We can complete the proof as in Case 5.2.

Case 7.3. contains just two of f, and .

We can complete the proof as in Case 5.3.

Case 7.4. contains f, and .

Case 7.4.1. f, and are all incident with x.

Let (resp. , ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. , ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing , and from , denoted by A. Notice that , so we connect , and to x. Combining them with A, we can get an extended star in .

Case 7.4.2. Just two of f, and are incident with x.

Without loss of generality, assumes that and are incident with x. Let (resp. , ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. , ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing , and from , denoted by A. Let be a 3-path containing f and starting at a, and then a is adjacent to x. The next proof can be completed as in Case 5.3.2.

Case 7.4.3. Just one of f, and is incident with x.

Without loss of generality, assumes that only is incident with x. Let (resp. , ) be a 4-path containing f (resp. , ) and starting at x in . A graph is obtained by removing , and from , denoted by A. Let be a 3-path containing f and starting at a, and then a is adjacent to x. The next proof can be completed as in Case 5.3.3.

Case 7.4.4. None of f, and is incident with x.

Then we consider whether f, and belong to the same path or not.

Case 7.4.4.1. f, and belong to the same path in .

Then we can complete the proof as in Case 2.2.2.

Case 7.4.4.2. f, and belong to different paths in .

Case 7.4.4.2.1. Just two of f, and belong to a path in .

Without loss of generality, assumes is a 3-path containing f and and starting at a, is a 3-path containing and starting at b. Then a and b are both incident with x. Then we can complete the proof as in Case 5.3.3.

Case 7.4.4.2.2. Each of f, and belong to a path in separately. Let (resp. , ) be a 3-path starting at a (resp. b, c), and it contains f (resp. , ). Then a, b and c are all incident with x. Notice that . It is easy to find a 3-path (resp. , ) that does contain a missing edge in (resp. , ), and (resp. , ) and (resp. , ) have no common vertices. Connecting (resp. , ) to a (resp. b, c), we can obtain a 3-path (resp. , ). Notice that , so we connect , , , , and to x. Combining them with , we can get an extended star in . □

Theorem 2.

Let be the n-dimensional wheel network with , and let be an arbitrary set of missing edges with . Then the diagnosability of has the strong local diagnosability feature for each node x in with missing edges , and the result is optimal with respect to the number of missing edges.

Proof.

By Lemmas 5 and 10, the local diagnosability of each node x in is equivalent to its remaining degree for and . By Lemma 6, each node in possesses the strong local diagnosability feature. By Lemma 7, possesses the strong local diagnosability feature.

Now a sample is provided to demonstrate that a wheel network may not keep the strong diagnosability feature if there are missing edges F. For an arbitrary node x in , x is labeled as a permutation on . Suppose that there are missing edges F in that are incident to x. Then, the remaining degree node adjacent to x in this incomplete wheel network with missing edges is 1. Let y be the just node adjacent to x. Let be the set of nodes with , and be the set of nodes with . Notice no link exist between and . Then the node set pair is not satisfied with the conditions (1)–(3) in Lemma 6, and hence is not -local diagnosable at y under the model. Because the local diagnosability of y (which is less than ) is not equivalent to its degree (which is ) in this incomplete wheel network , the node y has no strong local diagnosability feature anymore. Thus, an incomplete wheel network with missing edges cannot be guaranteed to have the strong local diagnosability feature. □

5. Conclusions

We considered the diagnosis of an n-dimensional wheel network under the model. Succeeding the notion of local diagnosability and the extended star structure suggested by Hsu and Tan [14], the diagnosability of a system may be derived straightforwardly. From the definition of the strong local diagnosability feature [14], we showed that an n-dimensional wheel network possesses the feature, and it preserves this strong feature even with up to missing edges in it. Consequently, the diagnosability of a wheel network with arbitrary missing edges can be obtained as the minimum value among the remaining degree of each CPU, if the cardinality of the set of missing edges is not larger than .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.F. and S.W.; funding acquisition, W.F. and S.W.; investigation, W.F.; methodology, W.F.; writing—original draft, W.F.; writing—review and editing, W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NSFC (61772010) and the foundation of IMUN (NMDGP17106) and the 2020 Scientific Research Project for Postgraduates of Henan Normal University (YL202008).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dahbura, A.T.; Masson, G.M. An O(n2.5) Fault identification algorithm for diagnosable systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1984, 33, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. Diagnosability of crossed cubes under the comparison diagnosis model. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2002, 13, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, P.L.; Tan, J.J.M.; Chang, C.P.; Hsu, L.H. Conditional Diagnosability Measures for Large Multiprocessor Systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2005, 54, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Preparata, F.P.; Metze, G.; Chien, R.T. On the connection assignment problem of diagnosable systems. IEEE Trans. Electron. Comput. 1967, EC-16, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsi, F.; Grandoni, F.; Maestrini, P. A Theory of Diagnosability of Digital Systems. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1976, C-25, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, J.; Malek, M. A comparison connection assignment for self-diagnosis of multiprocessor systems. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Fault-Tolerant Computing, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 24–26 June 1981; pp. 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, N.W.; Hsieh, S.Y. Structural Properties and Conditional Diagnosability of Star Graphs by Using the PMC Model. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2014, 25, 3002–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Jirimutu; Wang, S. The nature diagnosability of wheel graph networks under the PMC model and MM* model. ARS Comb. 2019, 143, 255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.K.; Tan, J.J.M.; Hsu, L.H.; Cheng, E.; Lipták, L. Conditional Diagnosability of Cayley Graphs Generated by Transposition Trees under the Comparison Diagnosis Model. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2008, 9, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.L.; Lin, C.K.; Tan, J.J.M.; Hsu, L.H. The g-good-neighbor conditional diagnosability of hypercube under PMC model. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 10406–10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. The 1-good-neighbor diagnosability of Cayley graphs generated by transposition trees under the PMC model and MM* model. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2017, 94, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The 1-good-neighbor connectivity and diagnosability of Cayley graphs generated by complete graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2018, 246, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, A.; Ma, X.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J. The g-good-neighbor conditional diagnosability of k-ary n-cubes under the PMC model and MM* model. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2015, 26, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, G.H.; Tan, J.J.M. A local diagnosability measure for multiprocessor systems. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2007, 18, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Tan, J.J.M. Using node diagnosability to determine t-diagnosability under the comparison diagnosis model. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2009, 58, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Hsu, G.H.; Shih, L.M.; Tan, J.J.M. Diagnosability of star graphs with missing edges. Inf. Sci. 2012, 188, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.; Liptàk, L.; Steffy, D.E. Strong local diagnosability of (n, k)-star graphs and Cayley graphs generated by 2-trees with missing edges. Inf. Process. Lett. 2013, 113, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, X. Diagnosability of alternating group graphs with missing edges. Recent Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2018, 11, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Diagnosability of bubble-sort graphs with missing edges. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2019, 19, 1950002-1–1950002-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, A.; Dahbura, A.T. On self-diagnosable multiprocessor systems: Diagnosis by the comparison approach. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1992, 41, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, M. A Comparison Connection Assignment for Diagnosis of Multiprocessor Systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Computer Architecture, La Baule, France, 6–8 May 1980; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Hsieh, S. Diagnosability of Component-Composition Graphs in the MM* Model. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2014, 19, 27:1–27:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Lu, J. On conjectures of interconnection networks. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2008, 44, 112–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford, T.W. Algebra; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Akers, S.B.; Krishnamurthy, B. A group-theoretic model for symmetric interconnection networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1989, 38, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Z.T.; Hsu, C.C.; Sheum, J.P. Bubble-sort star graphs: A new interconnection network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–6 June 1996; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Liu, H.; Lu, M. Fault-tolerant maximal local-connectivity on Bubble-sort star graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2015, 181, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, D. Structure connectivity and substructure connectivity of bubble-sort star graph networks. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 363, 124632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Hou, F.; Ma, J.; Wang, G. Study on diameter and average distance of wheel network. J. Gansu Sience 2012, 24, 103–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, F. Some New Results of the Wheel Networks and Bubble-Sort Star Networks; Northwest Normal University: Lanzhou, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).