An Empowerment Scale Analysis of Mexican MSMEs: Modeling with Covariance Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Empowerment

2.1. Economic and Management Theories Related to Empowerment

2.2. Approaches to Empowerment

2.3. Theoretical Construction of Research Variables and Hypotheses

- Meaning. The collaborator connects his values, beliefs, and behaviors with the goals and objectives of the company.

- Competition. The confidence the collaborator has in his abilities, skills, and knowledge to carry out his work independently of other collaborators.

- Self-determination. The autonomy and initiative that the collaborator has to choose and make decisions to execute and develop his activities.

- Impact. The collaborator’s perception of the consequences of his actions and his influence on the results of the company.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Instruments

3.3. Statistical Analysis

- m = number of items on the scale.

- xi = items on the scale.

- m = number of items on the scale.

- xi = items on the scale.

- −

- Chi-squared (χ2) following the maximum likelihood estimation method:The setting function iswhere,

- Tr = trace.

- Ln = natural logarithm.

- P = total number of estimated independent parameters.

- N = sample size.

- p + q = number of observable variables analyzed.

- df = degrees of freedom = 0.5 (p + q)(p + q + 1) − P.

- S = observed covariance matrix (initial).

- χ2 = Chi squared.

- ∑ = matrix of covariances reproduced by the model.

- −

- Goodness of fit index (GFI)where,

- Tr = trace.

- S = observed covariance matrix (initial).

- I = Identity matrix.

- −

- Comparative fit index (CFI).where,

- χ2 = Chi squared.

- df = degrees of freedom = 0.5 (p + q) (p + q + 1) − P.

- −

- Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)where,

- χ2 = Chi squared.

- df = degrees of freedom = 0.5 (p + q) (p + q + 1) − P.

- N = sample size.

- −

- Normed chi-square (NCS).where,

- χ2 = Chi squared.

- df = degrees of freedom = 0.5 (p + q) (p + q + 1) − P.

- −

- Composite reliability (CR).

- −

- Average variance extracted (AVE).where λ (lambda) is the standardized factor loading for item i, ε is the respective error variance for item i, and p is number of indicators observed variables.

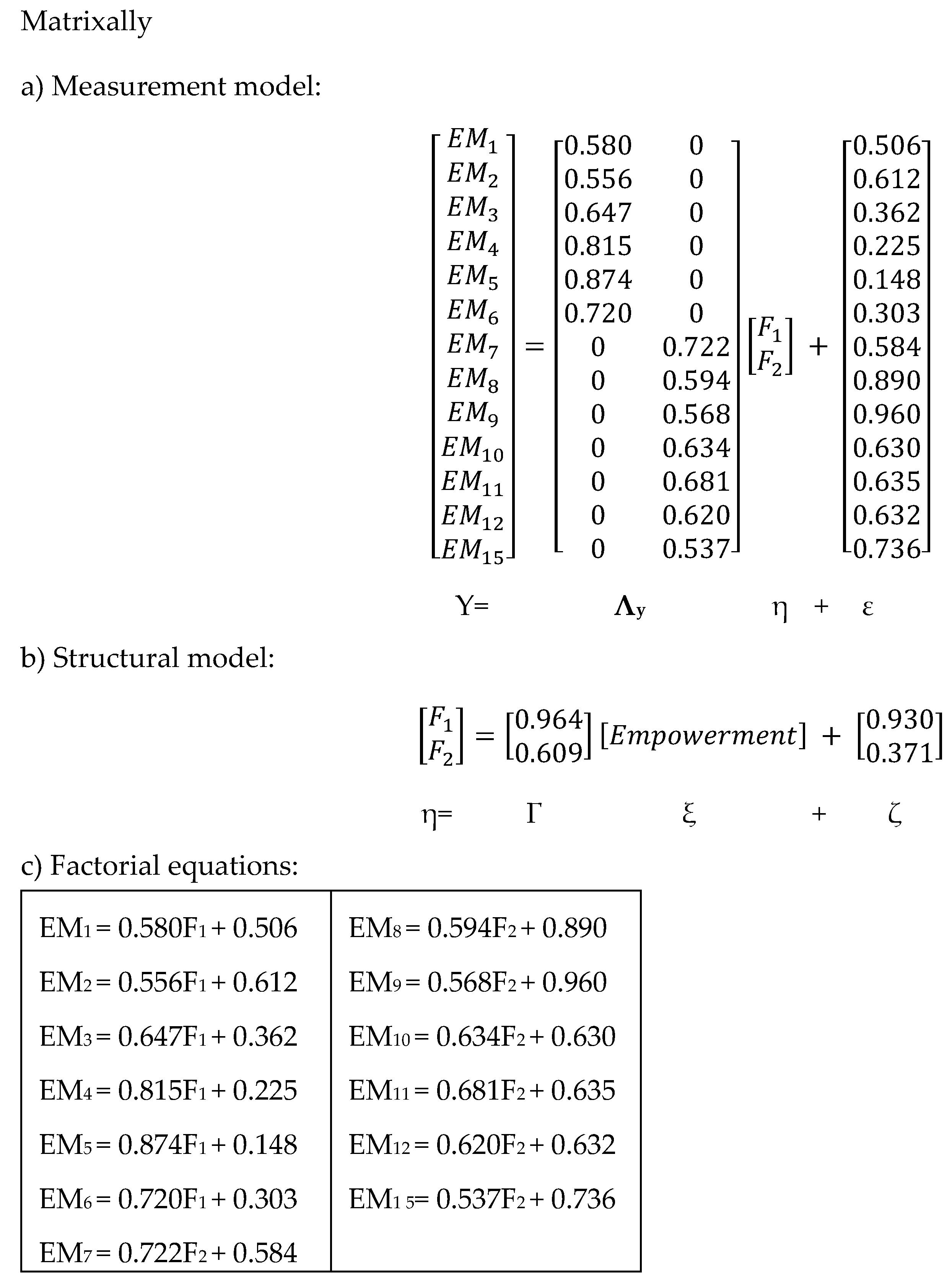

3.4. Formal Establishment of the Model Structure in Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.4.1. Specification of the Measurement Model

3.4.2. Structural Model Specification

E(YY´) = Λy(ΓΦΓ´ + Ψ) Λy´ + Θε

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

4.2. Validation of the Scale: Exploratory Factor Analysis

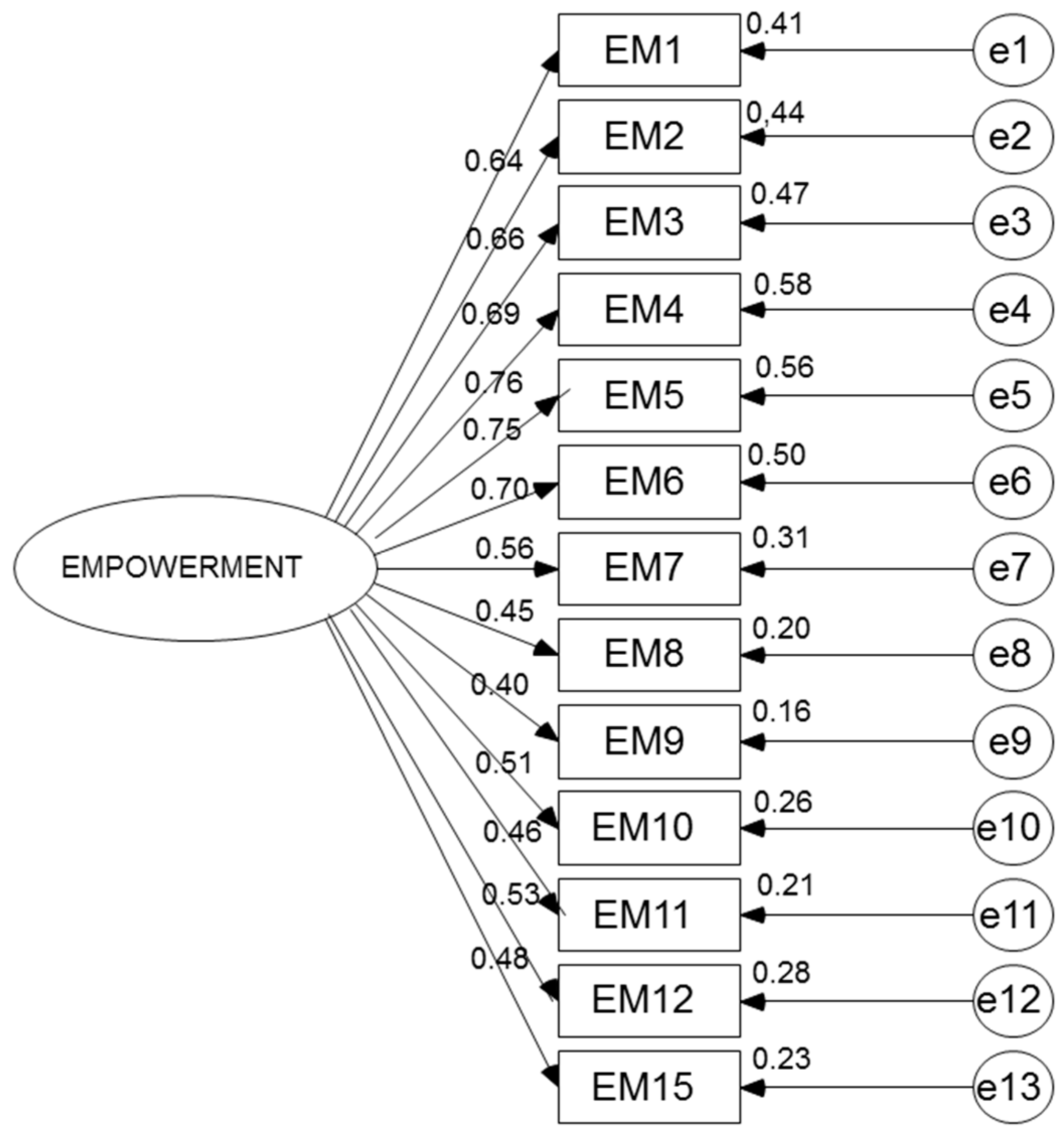

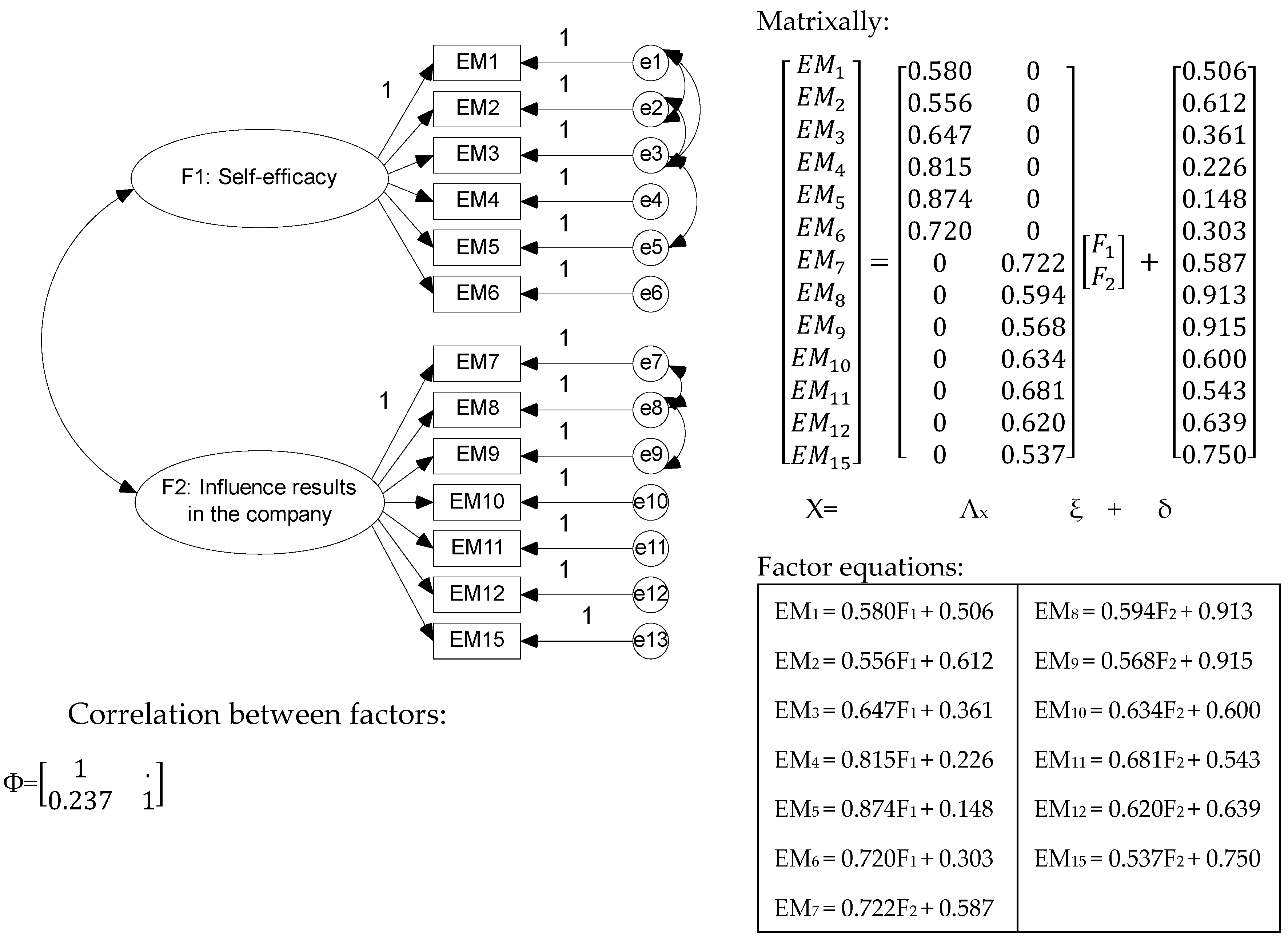

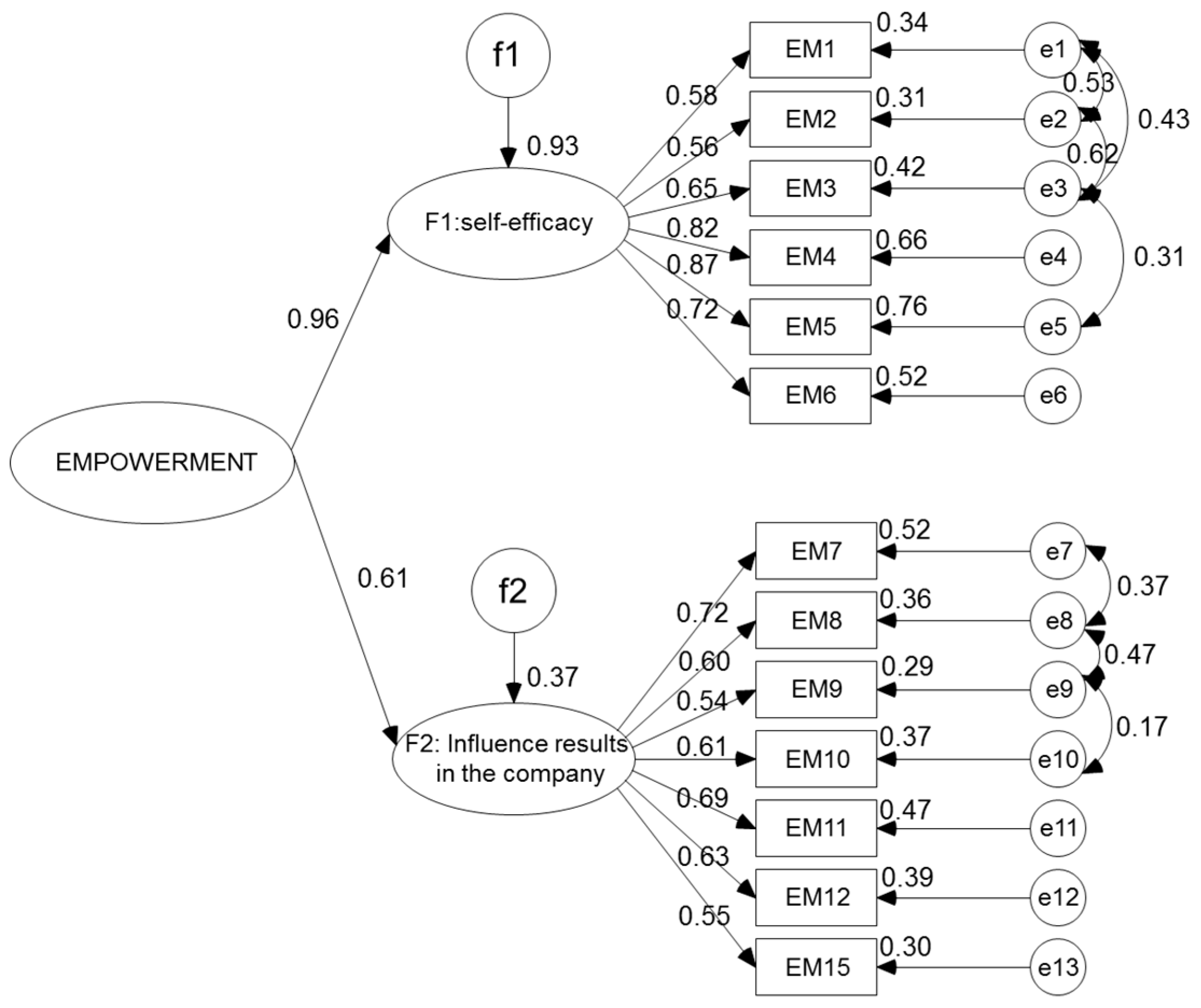

4.3. Second-Order Model: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| E1 | Importance of the work done by workers |

| E2 | Personal meaning of the activities carried out by the worker |

| E3 | Meaning of worker performance |

| E4 | Confidence in the collaborator’s ability |

| E5 | Confidence in the knowledge and skills of employees |

| E6 | Confidence that the employee has mastered their skills to carry out their activities |

| E7 | Confidence in the worker’s autonomy over their activities |

| E8 | Freedom granted to the collaborator to plan their activities |

| E9 | Freedom and independence granted to the collaborator to carry out their activities |

| E10 | Impact of the workers’ initiative |

| E11 | Control of collaborators over their work area |

| E12 | Collaborator influence on company results |

| E13 | Importance given to the worker’s educational level to grant authority |

| E14 | Training programs implemented in the company |

| E15 | Access to the information available to collaborators |

| E16 | Efficiency with which the company distributes information to employees |

| E17 | Expectation of remuneration for the work initiative |

| E18 | Prize and reward information available to collaborators |

| E19 | Information, about clients, available to collaborators |

| Note: Items that were removed appear in italics. | |

References

- Lee, M.; Koh, J. Is empowerment really a new concept? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, M.; Téllez, M.d.R.; Ferrer, J. El empowerment como predictor del compromiso organizacional. Contaduría y Administración 2010, 231, 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, R. Empowerment: Rejuvenating a potent idea. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2000, 14, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, A.; Adelpanah, A.; Soleimani, R.; Heidari-Aqagoli, P.; Eidizadeh, R.; Salehzadeh, R. The effect of psychological empowerment on job burnout and competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational commitment and creativity. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2020, 18, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriades, Z.S. Creating strategic capabilities: Organizational learning and knowledge management in the new economy. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2005, 17, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Antecedents and outcomes of employee empowerment practices: A theoretical extension with empirical evidence. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmenoglu, M.A. Investigating Benefits and Drawbacks of Employee Empowerment in the Sector of Hospitality. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context Psychology and Culture. Online Read. 2011, 2, 2037–2919. [Google Scholar]

- COLMEX. Desigualdades en México 2018; El Colegio de México. Red de Estudios sobre Desigualdades: Tlalpan, México, 2018; Available online: https://desigualdades.colmex.mx/informe-desigualdades-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- İzlem, G.; Nurdan, Ç.; Ömer, F.Ş. Development culture and TQM in Turkish healthcare: Importance of employee empowerment and top management leadership. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 30, 1302–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, R.A.; Diaz, W.M.; Cole, S.G. The organizational empowerment scale. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psicological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions measurment and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, R.; Grazzi, M. Innovation and entrepreneurship in Latín America: What do we know? What would we like to know? Estudios de Economía 2018, 45, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jáimez, M.J.; Bretones, F.D. El empowerment organizacional: El inicio de una gestión saludable en el trabajo. Revista de Trabajo y Seguridad Social. Recursos Humanos 2011, 344, 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, R.C. Refortalecimiento: Un debate con el empowerment. Revista Interamericana de Psicología 2004, 38, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, J. In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herriger, N. Empowerment in der Sozialen Arbeit: Eine Einführung, 6th ed.; Kohlhammer Verlag: Stuggart, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek, J.M.; Spreitzer, G.M. The interdisciplinary career of a popular construct used in management: Empowerment in the late 20th century. J. Manag. Inq. 2006, 15, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, J.R.; Alba, R.D. Empowering Nets of Participation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 27, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Acad. Mamag. Rev. 1988, 13, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Newstrom, J. Comportamiento humano en el trabajo; McGraw Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.T. Employee empowerment: An integrative psychological approach. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R. Empowerment ¿actitud mental?, ¿técnica?, ¿estrategia? o ¿moda? Trillas: Benito Juárez (CDMX), México, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S. El empowerment: La potenciación del bienestar desde la psicología comunitaria. In Gil-Lacruz, M. (Dir), Psicología Social y Bienestar: Una Aproximación Interdisciplinary; Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chee, H.E.; Zheng, H.L.; Kumar, R.; Ramendran, C.; Kadiresan, V. An Effectiveness of Human Resource Management Practices on Employee Retention in Institute of Higher learning: A Regression Analysis. Inter. J. Bus. Res. Manag. 2012, 2, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretative” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Manríquez, M.; López-Mateo, C.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.D. El capital humano como factor clave en el desempeño empresarial: Una visión desde el empowerment. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado 2019, 10, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, H.O.; Márquez, M.B.L. Relación del empowerment con el compromiso organizacional influenciado por el capital humanoy prácticas de alto involucramiento de empleados en maquiladoras automotrices. Glob. Conf. Bus. Financ. Proc. 2016, 11, 855–867. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, M.; Montes, C.; Vásquez, J.; Villegas, M.; Brito, T. Capital Humano: Una Mirada Desde la Educación y la Experiencia Laboral; Universidad EAFIT: Medellín, Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, R. Desarrollo del Capital Humano en las Organizaciones; Primera edición; Red Tercer Milenio: Estado de México, México, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alama, E.M. Capital Intelectual y Resultados Empresariales en las Empresas de Servicios Profesionales de España/Intellectual Capital and Business Results in Professional Services Companies in Spain. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. Thecornerstones of competitiveadvantage: A resource-basedview. Strategic Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, N.H.; Sánchez Tovar, Y.; Lavín Verástegui, J. Identificación de las capacidades empresariales como factor generador de la competitividad en el sector hotelero de la ciudad de Victoria, México. Revista de Investigación Administrativa 2014, 113, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, L. Competencias centrales y ventaja competitiva: El concepto, su evolución y su aplicabilidad. Revista de Contaduría y Administración 2003, 209, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, T.E.E.; Gutiérrez, G.L.B. Liderazgo con Empowerment: Promotor de la innovación. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia 2007, 12, 207–217. Available online: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1315-99842007000200004&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Quigley, J. Visión. Como la Desarrollan los Líderes, la Comparten y la Sustentan; Mc Graw Hill: Bogotá, Colombia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- De Talavera, D.M.; De Condoré, I. Empowerment como estrategia empresarial en organizaciones sociales. México SINNCO 2010, 1–26. Available online: https://docplayer.es/13388686-Empowerment-como-estrategia-empresarial-en-organizaciones-sociales.html#show_full_text (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, D.; Díaz, C.; Hernández, R. Evolución y principios de la teoría económica institucional: Una propuesta de aplicación para el análisis de los factores condicionantes de la creación de empresas/Evolution and principles of institutional economic theory: An application proposal for the analysis of the conditioning factors of business creation. Revista de Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa 2007, 13, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R. Prospering in dynarnically-competitive environrnents: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geovany, C.G.; Martinez, L.B.; Vigier, H.P.; Nuñez, J.J. El rol del Empowerment en el Exito Empresarial. Investigación Administrativa 2016, 117, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, S. Intrategia: Una Dimensión Básica de la Cultura Empresarial; Álvarez de Mon, C.S., Chinchilla, A., Millar, E., Pérez, L., Pin, A., Poelmans, I., Rodríguez, L., Rodríguez, P., Torres, A., Eds.; Paradigmas de Liderazgo; McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España, S.A: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. Taking stock: A review of more than twenty years of research on empowerment at work1. In Organizational Behavior; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, A. Tendencias del Management contemporáneo. In Proceedings of the Conferencia impartida en I Evento Nacional de Gestión Empresarial, Holguín, Cuba, 27 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, N.D.; Travers, C.; Ackers, P.; Wilkinson, A. TheMeaning of Empowerment: Theinterdisciplinaryetymology of a new management concept. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2002, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Zani, B. The relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational identification. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 41, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K. EmployeeEmpowerment: A Strategic Tool to Obtain Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Int. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Alles, M. Dirección Estratégica de Recursos Humanos Gestión por Competencias; Granica: Ciudad de México, México, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, D.T.; Scott, C.D. Empowerment; Oxford University Press: Ciudad de México, México, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murari, K.; Gupta, K.S. Impact of servant leadership on employee Empowerment. J. Strateg. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Kirkman, T.A.; Kirkman, B.L.; Zhang, P.; Lemoine, G.J.; Farh, J.L. Multiple Team Membership and Empowerment Spillover Effects: Can Empowerment Processes Cross Team Boundaries? J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquilena, D.; Portillo, I.M. Empowerment como Estrategia Empresarial en Organizaciones Sociales. México SINNCO. 2010. Available online: http://www.concyteg.gob.mx/formulario/MT/MT2010/MT13/SESION2/MT132_DMIQUILENAT_222.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Shedid, M. Employee Empowerment and Customer Satisfaction: An Investigation from a UAE Banking-Sector Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E.; Spreitzer, G.M. The road to empowerment: Seven questions every leader should consider. Organ. Dyn. 1997, 26, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Siegall, M.; Gardner, S. Contextual factors of psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Toward a common ground in defining empowerment. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 1997, 10, 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tymon, W.G. An Empirical Investigation of a Cognitive Model of Empowerment. Ph.D Thesis, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.R. Socialization tactics, self-efficacy, and newcomers’ adjustments to organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1986, 29, 262–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Salem, D.A.; Chibnall, S.L. Empirical support for the critical assumptions of empowerment theory. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, S.M.; Mohammed, E.A. Psychological Empowerment and Its Relation with Organizational Loyalty Among First Line Managers. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2018, 49, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: Expanding Kanter’s model. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.; Finegan, J.E.; Shamian, J.; Wilk, P. A longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empowerment on work satisfaction. J. Organ. Behaiv. 2004, 25, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. Empowerment theory. Handbook of Community Psychology; Rappaport, J., Seidman, E., Eds.; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, P.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C. Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment and work engagement/burnout. Nurs. Leadersh. 2006, 19, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.; León, J.C.; Orgambídez, A.; Borrego, Y. Evidencias de validez de la adaptación española de la Organizational Empowerment Scale. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 2009, 25, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, A.; Abeal, J.P.; Faíña, J.A. Transformational leadership and work engagement: Exploring the mediating role of structural empowerment. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Kumar, C.; Sharma, R. Team building, employee empowerment and employee competencies: Moderating role of organizational learning culture. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Silén, M.; Skytt, B.; Engström, M. Relationships between structural and psychological empowerment, mediated by person-centred processes and thriving for nursing home staff. Geriatr. Nurs. 2019, 40, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sarkar, A. Role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between structural empowerment and innovative behavior. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, L.J.; Stelly, D.J.; Trusty, M.L. Defining and Measuring Empowering Leader Behaviors: Development of an Upward Feedback Instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Borrego-Alés, Y.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Empowerment, vulnerabilidad al estrés y burnout en enfermeros portugueses. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2018, 23, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G.M.; West, A.M.; Wall, D.T. Integrated manufacturing, empowerment, and company performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 641–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.K.; Dowling, M.; Raghuram, S. Empowerment as a success factor in start-up companies. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2007, 1, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyamtinah, H.S. Innovation capability of SMEs through entrepreneurship, marketing capability, relational capital and empowerment. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2016, 21, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Vélez, H.D. Empowerment como Estrategia Gerencial para Mejorar la Efectividad Laboral. Revista Científica FIPCAEC Fomento De La Investigación Y Publicación En Ciencias Administrativas, Económicas Y Contables 2017, 2, 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza Sierra, M.I.; Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Borrego Ales, Y.; Gonçalves, G.; Santos, J. Translate into Spanish of the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ II). Universitas Psychologica 2014, 13, 923–934. [Google Scholar]

- Stander, M.W.; Rothmann, S. Psychological empowerment, job insecurity and employee engagement. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, K. Empowerment, 3 Claves Para Lograr que el Proceso de Facultar a los Empleados Funcione en su Empresa; Norma Ediciones: Ciudad de México, México, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saengchai, S.; Siriattakul, P.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Exploring the link between HRPractices, Employee Motivation, Employee Empowerment and Employee Performance in Engineering Firms of Indonesia. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2019, 23, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A.; Bhutta, Z.M.; Nauman, M.; Zahra, S. Enhancing performance and commitment through leadership and empowerment: An emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Y. Why firms adopt empowerment practices and how such practices affect firm performance? A transaction cost-exchange perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, M. Impacto de la capacitación en la mejora de la productividad en una planta de lubricantes. Crescendo 2017, 8, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñán-Villagrán, J.A.; García-Liut, E.G.; Caicedo-Benavides, F.U. Incidencia del sistema de compensación en el desempeño laboral de los colaboradores de la Corporación Nacional de Telecomunicaciones. Dominio de las Ciencias 2020, 6, 740–762. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Massoud, J.A. The role of training and empowerment in environmental performance: A study of the Mexican maquiladora industry. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaemek, A.A.; Okoro, A.; Rejoice, O.E. capacitación tiene un efecto significativo sobre la productividad en las organizaciones manufactureras. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Moura, D.; Almeida, H.D. Estrés de rol y empowerment psicológico como antecedentes de la satisfacción laboral. Rev. Psicol. 2017, 35, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, J.; Gonçalves, G.; Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Mendoza-Sierra, M.I.; Borrego-Alés, Y. Estudo de adaptação da escala de empowerment psicológico de Spreitzer (1995) numa amostra portuguesa. Aval. Psicol. 2014, 13, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- DENUE Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). DENUE Interactivo. 2018. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/ (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting Common Method Bias: Performance of the Harman’s Single-Factor Test. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2019, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M. Structural Equation Modeling: Threshold Criteria for Assessing Model Fit. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Subudhi, R.N., Mishra, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: London, UK, 2019; pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.M.; Sarabia, S.F.J. Validez y fiabilidad de escalas. Metodología Para la Investigación en Marketing y Dirección de Empresas; Sarabia, S.F.J., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 363–393. [Google Scholar]

- Albarrán, V.; Geldres, V.; Paredes, P.; Ramirez, O.; Ruiz, F.; Palomino, C. Validación de la batería de instrumentos para la evaluación de factores de riesgo psicosocial. Horizonte Médico 2018, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS/PC + Step by: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrou, I. Análisis factorial exploratorio: Cuestiones conceptuales y metodológicas. Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Lisrel, Prelis, and Simplis: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.H.; Pflesser, C.H. A multiple liar model market-oriented organizational culture: Measurement issues and performance outcomes. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, P.R.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D.; An, J.; Hancock, G.R. The Thorny Relation between Measurement Quality and Fit Index Cutoffs in Latent Variable Models. J. Personal. Assess. 2018, 100, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Shi, D.; Rosseel, Y. Assessing Fit in Structural Equation Models: A Monte-Carlo Evaluation of RMSEA Versus SRMR Confidence Intervals and Tests of Close Fit. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2018, 3, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Cook, K.F.; Crane, P.K.; Teresi, J.A.; Cella, D. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med. Care 2007, 45, S22–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Mallou, J.; Lévy-Mangin, J.P. Modelización con Estructuras de Covarianzas en Ciencias Sociales. In Temas Esenciales, Avanzados y Aportaciones Especiales; Netbiblo: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes, F.; Rosseel, Y.; Textor, J. Local fit evaluation of structural equation models using graphical criteria. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengchai, S.; Siriattakul, P.; Jermsittiparsert, K. HR Practices, Overall Satisfaction and Employee Loyalty: Does Corporate Social Responsibility Matter in Mining firms of Indonesia? Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2019, 23, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Matrix | Parameter | Dimensions | Covariances | Dimensions | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ξ | ξ (ksi) | n × 1 | Φ = E (ξξ´) | n × n | Exogenous latent variables |

| X | x | q × 1 | ∑ = E (´) | q × q | Exogenous observable variables |

| Λx Λy | λ (lambda) | q × n p × m | -- | -- | Factor loads of X on ξ Factor loads of Y on η |

| δ | δ (delta) | q × 1 | Θδ = E (δδ´) | q × q | X measurement errors |

| η | η (eta) | m × 1 | Cov(η) = E (ηη´) | m × m | Endogenous latent variables |

| ζ | Ζ (zeta) | m × 1 | Ψ = E (ζζ´) | m × m | Measurement errors of η |

| B | Β (beta) | m × m | -- | -- | Direct effects of η on η |

| Γ | Γ (gamma) | m × n | -- | -- | Direct effects of ξ on η |

| Y | Y | p × 1 | E (YY´) | p × p | Endogenous observable variables |

| ε | Ε (epsilon) | p × 1 | Θε = E (εε´) | p × p | Measurement errors of Y |

| Constructs | Scale Items 1 | Correlation Item-Total | Mean | Standard Deviation | Exploratory Factor Analysis (Loadings) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |||||

| Empowerment (α Cronbach: 0.870) | EM1 | 0.482 | 5.60 | 0.875 | 0.821 0.847 0.839 0.732 0.687 0.614 | 0.794 0.818 0.758 0.595 0.709 0.532 -- -- 0.475 |

| EM2 | 0.510 | 5.44 | 0.943 | |||

| EM3 | 0.550 | 5.59 | 0.801 | |||

| EM4 | 0.629 | 5.47 | 0.822 | |||

| EM5 | 0.612 | 5.41 | 0.795 | |||

| EM6 | 0.611 | 5.41 | 0.795 | |||

| EM7 | 0.639 | 4.81 | 1.111 | |||

| EM8 | 0.538 | 4.64 | 1.209 | |||

| EM9 | 0.483 | 4.77 | 1.165 | |||

| EM10 | 0.548 | 5.08 | 1.003 | |||

| EM11 | 0.32 | 4.81 | 1.008 | |||

| EM12 | 0.543 | 5.21 | 1.021 | |||

| EM13 | Eliminated | 4.42 | 1.537 | |||

| EM14 | Eliminated | 4.31 | 1.512 | |||

| EM15 | 0.479 | 5.15 | 1.029 | |||

| EM16 | Eliminated | 4.01 | 1.549 | |||

| EM17 | Eliminated | 4.69 | 1.338 | |||

| EM18 | Eliminated | 4.20 | 1.738 | |||

| EM19 | Eliminated | 4.33 | 1.671 | |||

| Own value | 3.820 | 3.603 | ||||

| % factor explained variance | 29.384 | 27.718 | ||||

| % cumulative explained variance | 29.384 | 57.102 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of Sphericity Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin index 2 | χ2(sig.): 1396.883 (0.000); KMO: 0.844; Measure of simple adequacy: (0.897–0.918); % variance: 57.102 | |||||

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2(df) | P | GFI | AGFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | PRATIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1—(1 variable—13 items) | 590.438 | 65 | 9.084 | 0.000 | 0.611 | 0.508 | 0.534 | 0.611 | 0.191 | 0.833 |

| Model 2—1st order (2 oblique factors—13 items) | 331.406 | 64 | 5.178 | 0.000 | 0.792 | 0.704 | 0.759 | 0.802 | 0.137 | 0.821 |

| Model 3—1st order (2 orthogonal factors—13 items) | 368.100 | 65 | 5.663 | 0.000 | 0.784 | 0.698 | 0.731 | 0.776 | 0.145 | 0.833 |

| Model 4—1st order (Model 2 re-specified- 2 variables—13 items) | 100.714 | 58 | 1.736 | 0.000 | 0.937 | 0.902 | 0.958 | 0.968 | 0.058 | 0.744 |

| Model 5—2nd order (3 variables—13 items) | 94.148 | 57 | 1652 | 0.001 | 0.941 | 0.905 | 0.962 | 0.973 | 0.054 | 0.731 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Ríos-Manríquez, M.; Álvarez-García, J.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.D. An Empowerment Scale Analysis of Mexican MSMEs: Modeling with Covariance Structures. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8101817

del Río-Rama MdlC, Ríos-Manríquez M, Álvarez-García J, Sánchez-Fernández MD. An Empowerment Scale Analysis of Mexican MSMEs: Modeling with Covariance Structures. Mathematics. 2020; 8(10):1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8101817

Chicago/Turabian Styledel Río-Rama, María de la Cruz, Martha Ríos-Manríquez, José Álvarez-García, and María Dolores Sánchez-Fernández. 2020. "An Empowerment Scale Analysis of Mexican MSMEs: Modeling with Covariance Structures" Mathematics 8, no. 10: 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8101817

APA Styledel Río-Rama, M. d. l. C., Ríos-Manríquez, M., Álvarez-García, J., & Sánchez-Fernández, M. D. (2020). An Empowerment Scale Analysis of Mexican MSMEs: Modeling with Covariance Structures. Mathematics, 8(10), 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8101817