1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is rapidly expanding toward tens of billions of interconnected devices, which is expected to increase the diversity of communication protocols, application services, and overall traffic volumes in operational networks. Recent industry forecasts estimate approximately 38–39 billion IoT connections by 2030, with robust growth in industrial and smart city deployments [

1,

2]. This scale and heterogeneity further complicate traffic management, as IoT networks host a mix of benign application flows and malicious activities (scanning and botnet traffic) that can directly undermine security monitoring and degrade the Quality of Service (QoS).

QoS requirements in IoT are also application dependent and often conflicting. For instance, smart healthcare services are commonly constrained by real-time demand and low-latency requirements, where delays can degrade monitoring and decision support [

3,

4]. In contrast, multimedia and video-oriented IoT services (e.g., surveillance and streaming) are highly sensitive to bandwidth fluctuations, buffering, and stalling events that degrade the Quality of Experience (QoE) [

5,

6]. These practical constraints strengthen the case for accurate traffic classification, since classification enables policy enforcement, anomaly detection, and QoS-aware scheduling.

Traditional traffic classification methods, such as port-based identification and payload inspection, are largely static and struggle to remain effective in modern IoT networks. With the rapid emergence of new applications and evolving protocols, and the increasing use of encryption, these conventional approaches become less reliable for accurate traffic identification [

7]. Machine learning (ML)-based techniques improve adaptability by leveraging statistical and temporal features. However, their performance remains strongly dependent on the quality and completeness of the extracted features [

8]. Deep learning (DL) methods further reduce this dependency by learning discriminative representations directly from raw packets or flows, enabling the improved recognition of complex traffic behaviors [

9].

Nevertheless, many existing DL-based classifiers focus on a single traffic characteristic (e.g., spatial, temporal, or frequency domain), which can limit their robustness and lead to incomplete classification in realistic IoT scenarios [

10,

11,

12]. This limitation encourages the adoption of feature diversity, since different feature categories capture complementary traffic behaviors and can strengthen discrimination across heterogeneous conditions. Specifically, general statistical features (e.g., packet size, inter-arrival time, and throughput) provide a coarse-grained characterization of application traffic. Conversely, CNNs are well-suited to learn protocol and flow signatures using spatial features generated from payload/byte-level distributions [

13]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and LSTM networks can efficiently describe temporal properties represented as packet sequences to capture time-dependent correlations inside flows [

14]. In addition, statistical features (e.g., variance and skewness) capture burstiness and jitter effects, which are commonly observed in real-time traffic [

15]. While transform-domain features expose periodic patterns that may be weak in the time domain [

16]. Therefore, relying on a single representation is frequently insufficient for consistent multiclass classification in real-world IoT deployments.

Ensemble deep learning approaches seek to improve traffic classification by combining the outputs of multiple models trained to learn complementary feature representations [

17]. Common ensemble strategies include model averaging, bagging, boosting, and Mixture of Experts (MoE), where several base learners are encouraged to specialize in different characteristics of network traffic. For instance, CNNs are effective at capturing spatial relationships in packet-level representations, whereas LSTMs are well suited for modeling temporal dependencies in traffic flows. In addition, some ensemble designs incorporate autoencoders or transformer-based encoders to extract higher-level semantic representations prior to decision fusion. By aggregating predictions from diverse learners, ensemble learning can yield more accurate and robust classification performance than a single model [

18].

Despite this, one of the most prominent drawbacks of ensemble models for DL tasks remains a lack of coordination among feature learning tasks. Although a number of tasks within an ensemble might be learned toward distinct features, feature fusion might often be performed at a later stage (i.e., for outputs directly), thus neglecting the relationships among those features [

19,

20]. Additionally, conventional ensembles may fail to adapt to input-specific properties dynamically. As a consequence, such ensembles may be less likely to focus on more informative features for a particular data observation [

21,

22]. Furthermore, training and executing ensemble models tends to be more complex and consumes additional memory. This might limit such models for use cases in real-time environments in the Internet of Things. MoE models mitigate these limitations by using a gating function to route each input to specialized expert networks. This enables input-adaptive computation and encourages expert specialization. However, MoE-based routing and fusion remain underexplored for IoT traffic classification. In particular, limited work has investigated how to jointly exploit multi-view traffic representations while maintaining robust generalization across datasets and realistic traffic variability [

23].

Existing DL traffic classifiers often focus on a single feature view, which can limit robustness under heterogeneous IoT traffic conditions. Ensemble models can incorporate multiple feature views, but they commonly rely on late, fixed fusion of model outputs, which weakly coordinate feature learning and cannot adapt expert contributions to each input flow. Moreover, MoE-based input-adaptive routing and fusion remain relatively underexplored for IoT traffic classification. These gaps motivate a feature-specialized MoE design that learns complementary traffic representations through dedicated experts and combines them via dynamic gating and attention-based fusion to produce feature-aware decisions.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We develop an attention-driven Mixture of Experts (MoE) ensemble composed of five deep networks, such as Dense, CNN, GRU, CAE, and LSTM. Each network specialized to learn a distinct traffic modality (general, spatial, statistical, frequency domain, and temporal), enabling a comprehensive representation of heterogeneous IoT traffic.

We introduce a dynamic gating network that assigns context-aware weights to expert predictions. This enables the model to adaptively emphasize the most informative feature views for each input flow, including encrypted or VPN-obfuscated traffic.

We propose an Attention-based Learnable Fusion (ALF) module that integrates gated expert outputs via learnable attention scores, producing robust final decisions while improving coordination among experts.

We evaluate ALF-MoE on three public benchmark datasets (ISCX VPN-nonVPN, Unicauca, and UNSW-IoTraffic) and demonstrate consistent improvements over baseline and ablated variants in terms of accuracy and the F1-score.

2. Related Work

The Internet of Things (IoT) connects diverse devices ranging from sensors and healthcare equipment to industrial machines. This connectivity enables continuous data streaming through widely used application protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), the Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP), and the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) (MQTT, CoAP, and HTTP are application layer communication protocols widely used to exchange data between IoT devices and services). The diverse range of IoT applications, including healthcare monitoring, smart city services, and autonomous transportation, generates large volumes of complex and heterogeneous traffic [

24]. However, IoT environments also face strong dynamism due to traffic congestion, security threats, protocol incompatibilities, and varying Quality of Service (QoS) requirements, which complicate reliable network management. As a result, traffic classification has become a critical capability for accurately identifying traffic types and supporting monitoring, control, and security in IoT networks [

17]. Reliable traffic analysis is increasingly important for understanding device-specific communication behavior and supporting scalable learning-based network intelligence under evolving conditions [

25,

26].

Traditional traffic classification methods typically rely on port numbers and payload inspection. Port-based classification uses well-known ports to identify applications, but its effectiveness has declined due to the widespread use of dynamic ports and tunneling protocols. Payload-based analysis examines packet contents for classification, but it becomes unreliable as encryption standards such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.3 become more widely adopted. In addition, Virtual Private Network (VPN) tunneling further restricts payload visibility, as traffic remains encrypted and unavailable for direct inspection. Moreover, port- and payload-driven approaches do not adapt well to rapidly evolving traffic patterns and newly introduced cloud services [

7].

Machine learning (ML)-based traffic classification uses algorithms such as decision trees, support vector machines (SVMs), k-nearest neighbors (KNNs), and random forests to classify traffic based on extracted features. These methods often outperform conventional approaches because they learn from observed data rather than relying on fixed rules [

8]. However, ML models typically require manual feature design and expert knowledge to define suitable traffic features, such as packet sizes, inter-gap time, and flow time. Since traffic patterns change continuously with new applications and protocols, ML models often need frequent retraining to maintain high classification performance. In addition, complex traffic data can be difficult for traditional ML methods because it may contain a hierarchical structure and non-linear relationships among traffic variables [

10].

A study in [

27] investigates how machine learning can modernize existing network infrastructure and improve performance. It reports that ML-based traffic classification performs better in Software-Defined Networking (SDN) environments than traditional methods, enabling more efficient and adaptive traffic handling. The authors also note that integrating ML can strengthen SDN security. However, the study highlights that SDN and machine learning solutions still face scalability and performance challenges. It also points to open research directions, including more efficient data labeling, maintaining and updating models to sustain classification accuracy, and linking classification improvements to better QoS. In [

28], the authors propose an SDN architecture that combines ML with network slicing to improve scalability, automation, and real-time traffic management. The framework applies feature scaling and k-means clustering to divide traffic and assign optimal network slices. Among the five machine learning models evaluated, a feed-forward network achieves the highest accuracy of 98.2%. The work also emphasizes a key unresolved issue: collecting suitable data for real-time traffic classification and slice assignment remains difficult, which affects QoS.

Ensemble methods and hybrid techniques that combine SVMs, decision trees, and neural networks have shown strong effectiveness for traffic classification by leveraging the complementary learning capabilities of multiple classifiers. These approaches often improve generalization and robustness in large-scale networks, particularly when traffic distributions are complex and diverse, and they can reduce the risk of overfitting. Alash et al. [

29] integrated a packet-level traffic classification scheme based on XGBoost into an SDN architecture. Their method extracts EarlyStagePacket features directly in the SDN data plane, reducing the overhead on the SDN controller. However, the scheme achieves only about 91.8% accuracy on practical datasets and remains vulnerable to traffic encryption. Omanga et al. [

30] proposed a hybrid scheme combining SVM and a multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifiers for flow-level traffic classification. While it is effective for traffic usage profiling, it is not suitable for multi-class traffic classification under VPN traffic conditions.

Deep learning (DL) models are often more effective for classification because they can automatically learn features directly from raw data. Unlike traditional approaches that depend heavily on manual feature engineering, DL models can handle both simple and complex patterns, and they typically perform better on large-scale classification tasks. Recent studies, such as [

31,

32], apply image-based representations of packets and use Vision Transformers (ViT) and CNNs for traffic classification. Specifically, ref. [

31] proposes a gray-scale image transformation combined with ViT and CNN to classify traffic without handcrafted features. Similarly, ref. [

32] introduces ATVITSC, which integrates a vision transformer with LSTM-based spatiotemporal learning and dynamic weights to improve the learning of encrypted traffic features. Although image-based inputs simplify preprocessing, relying primarily on visual representations may limit the model’s ability to capture temporal and statistical characteristics important in dynamic traffic.

As discussed in [

33,

34,

35,

36], transformer models handle diverse traffic patterns using masked autoencoders and self-attention. In [

33], the authors propose a traffic transformer that combines a masked autoencoder with hierarchical attention at both the flow and packet levels. This design improves multi-level feature extraction, but it still relies on static fusion strategies. In [

34], MTC-MAE is introduced for malware traffic classification using self-supervised pretraining and fine-tuning to reduce label dependence, yet it does not include dynamic expert adjustment. EncryptoVision in [

35] extends transformer-based modeling with dual-modal fusion via triplet attention and transformer encoding to better capture temporal evolution and spatiotemporal dependencies, but its fusion remains inflexible. In [

36], EAPT uses adversarial pretraining to tokenize encrypted traffic, and applies disentangled attention, which supports lightweight architectures. However, it primarily targets adversarial robustness and places less emphasis on multi-modal feature fusion.

Methods for temporal and spatiotemporal modeling are discussed in [

37,

38]. In [

37], the L2-BiTCN-CNN model combines BiTCN and CNN layers to extract hierarchical features from bytes and sessions. This design supports multi-scale feature extraction with attention mechanisms, but its adaptability to heterogeneous traffic remains limited. Bimodal TrafficNet in [

38] integrates a vision transformer branch with a statistical feature branch. It uses cross-attention over statistical features to enhance feature combination. However, its final fusion layer is static, which restricts dynamic adaptability. Works [

39,

40] focus on feature interpretability and model robustness. In [

39], feature selection improves interpretability, but it relies on manually designed features. In [

40], the emphasis is on model adaptability and robustness against traffic classification attack scenarios. The study mainly provides a vulnerability analysis of deep learning-based traffic classification under adversarial attacks.

Recent research has proposed diverse ensemble and hybrid deep learning models for traffic classification in IoT and 5G networks. Study [

41] combined an ensemble of autoencoders with an SVM for traffic analysis in 5G slicing networks and showed strong robustness under class-imbalanced conditions, but the method remained limited in scope. Work [

18] introduced a tree-based ensemble with a deep learning meta-model for network traffic classification, improving generalization but relying heavily on decision tree-based learners. In [

17], traffic imbalance in software-defined IoT was addressed using cost-sensitive XGBoost with active learning, where applications are dynamically weighted to improve accuracy and reduce computational cost. However, the approach is constrained by feature-dependent processing. To handle evolving traffic patterns, ref. [

42] proposed Bot-EnsIDS, which integrates bio-inspired optimizers with a CNN–LSTM hybrid deep learning model and captures spatiotemporal features, but it requires extensive training epochs. Meanwhile, ref. [

43] presented AEWAE, a drift-adaptive ensemble framework optimized using PSO and designed for concept drift in imbalanced IoT streams. Nevertheless, it focuses mainly on anomaly-style settings rather than general multi-class traffic classification. Overall, these models advance robustness and dynamic feature learning, but limitations such as feature dependency, computational overhead, and limited generalizability persist.

Mixture of Experts (MoE) is an ensemble-style learning approach that divides a model into multiple expert subnetworks and a gating network. The gating network selects the most suitable expert, or a small subset of experts, for each input sample. MoE is not a new concept. It was introduced in the early 1990s, with the classic formulation reported in 1991 [

44]. The framework was further extended in the mid-1990s, including hierarchical mixtures of experts proposed by Jordan and Jacobs in 1994 [

45]. MoE regained strong attention in modern deep learning after the sparsely gated MoE model by Shazeer et al. (2017), which demonstrated efficient scaling through sparse routing [

46]. Today, MoE is well-suited to network traffic classification because traffic is highly heterogeneous across applications, devices, protocols, and usage patterns [

47]. Experts can specialize in complementary feature views, such as temporal behavior, statistical patterns, header-level cues, and characteristics of encrypted or VPN traffic. Sparse routing also improves efficiency, since only selected experts are activated for each flow, increasing capacity without paying the full inference cost every time.

Recent MoE-based studies show that expert routing can improve both the accuracy and efficiency of traffic analysis, especially under encryption and heterogeneous conditions. The work [

48] uses a teacher–student distillation strategy and treats compact GPT-2-derived models as experts, which are selected by a gating network for encrypted traffic classification. Its main advantage is a strong accuracy–efficiency trade-off through distillation, pruning, and contextual feature embedding, which supports resource-constrained edge deployment. However, it depends on LLM-style components and careful distillation, which increases implementation complexity. The proposed method in [

49] combines contrastive learning with a Vision Mixture of Experts by constructing a packet–temporal matrix and applying dynamic expert routing in a vertical ViT-MoE design. It improves representation learning and generalization with limited labels, but its image-like representation and transformer-based routing can increase computational cost and require careful tuning for stable training.

The work in [

50] uses a multi-gated MoE design with multiple expert sub-models and a final tower network. Its main strength is its scalability, because it can integrate pretrained experts and support task expansion over time. This makes it suitable for multi-attribute prediction, such as application type, encapsulation usage, and malicious behaviors. However, multiple gates and expansion modes increase the system’s complexity and require careful coordination during training and deployment. Traffic-MoE [

51] targets real-time and throughput-sensitive environments by sparsely routing inputs to only a small subset of experts. It improves throughput, and reduces latency and memory usage, but it relies on specialized routing and pretraining pipelines that may be sensitive to distribution shifts. A simpler MoE [

47] that combines Dense, CNN, and LSTM experts is easy to implement and captures complementary feature views. However, full input expert processing can still add overhead and may not address encryption or drift unless explicitly evaluated.

Table 1 shows the limitations and advantages of the existing works.

3. Methodology

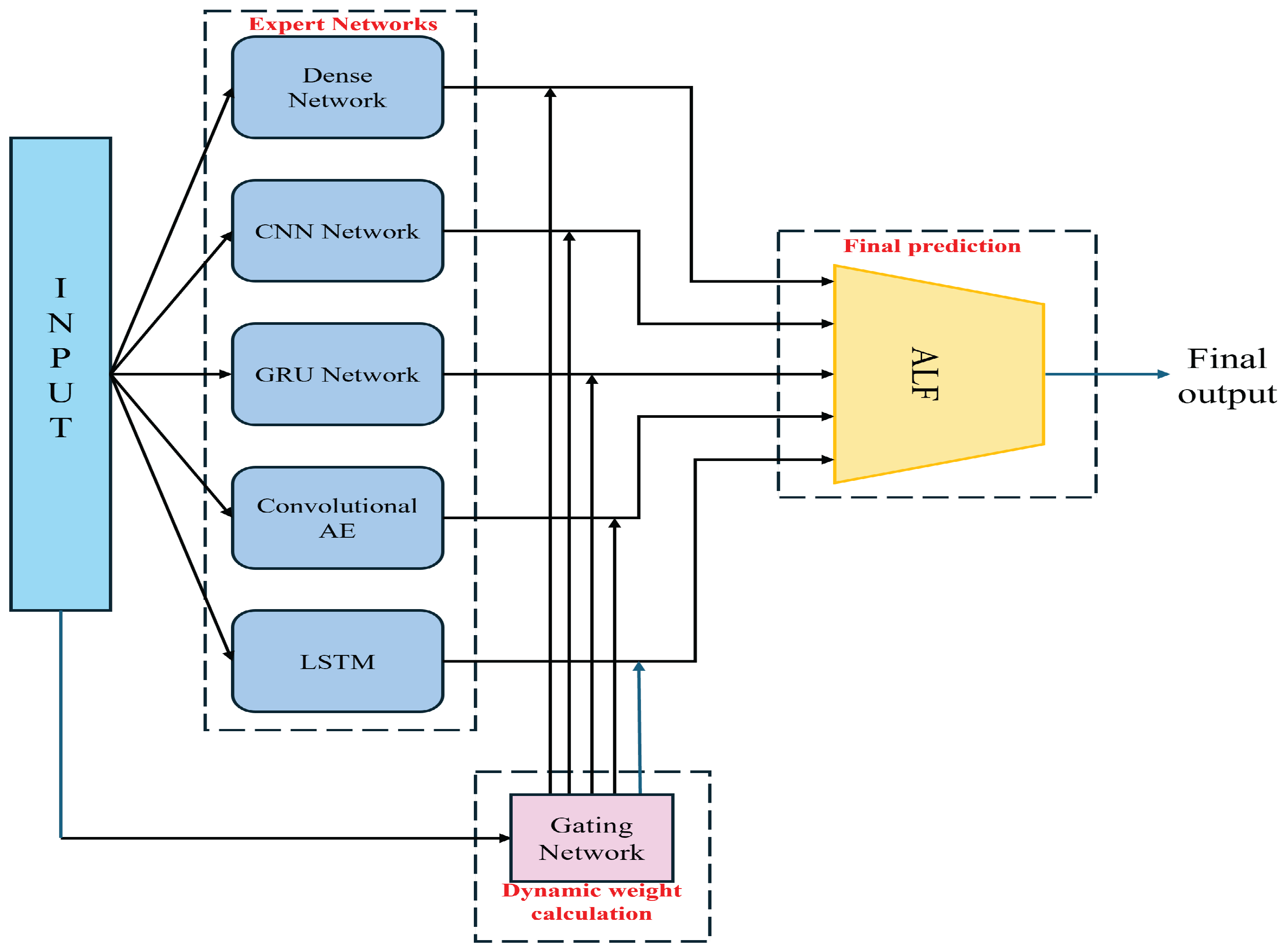

This section introduces the proposed Attention-based Learnable Fusion of Specialized Mixture of Expert Networks (ALF-MoE) for accurate traffic classification. ALF-MoE is an ensemble deep learning framework designed to enhance traffic classification by integrating five specialized expert networks, such as Dense, CNN, GRU, Convolutional Autoencoder, and LSTM. Each expert independently processes the complete input to capture unique characteristics from different feature domains. A dynamic gating network computes context-aware attention weights for each expert output. These attention-weighted predictions are subsequently fused through the Attentive Learnable Fusion (ALF) module, enabling robust and accurate final classification. ALF-MoE’s overall architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

Table 2 shows the mathematical notations used in this paper.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

The input consists of raw network traffic data from different applications. Let the dataset be denoted as , where is the traffic sample and is its class label among C classes. Each sample is represented by a raw feature vector extracted from the dataset.

To avoid leakage-driven performance, we explicitly remove all direct identifiers from when present, including the source/destination IP addresses, source/destination ports, flow/session identifiers, and timestamps. The resulting feature vector is denoted as .

All continuous features in

are standardized using z-score normalization:

where

and

are the per-feature mean and standard deviation.

3.2. Expert Networks

Feature extraction is essential for traffic classification. Using informative features can improve accuracy and reduce computation and memory cost. However, a single deep learning model usually focuses on one feature type. This can limit performance, reduce generalization, and increase overfitting.

To address this, the proposed ALF-MoE processes each input instance with multiple experts. Each expert learns a different representation of the same traffic sample. We construct five feature domains: general (), spatial (), statistical (), frequency (), and temporal (). These domains are derived deterministically from and passed to their corresponding experts. Let , , , , and denote the domain-specific inputs for sample .

From the normalized feature vector , we build five domain inputs using fixed lengths , and and a fixed feature order. Therefore, the same sample always produces the same tensors.

3.3. Expert Networks Class Prediction

3.3.1. Dense Network Expert

The Dense Network expert is designed to capture global, non-sequential statistical characteristics from traffic data. It processes the general feature vector

, extracted from the input sample

, which includes flow-level attributes such as packet count, byte count, flow duration, and entropy-based measures. To model complex, non-linear interactions among these general features, a two-layer feed-forward neural network is used. Each layer applies an affine transformation followed by a non-linear activation function. The output representation

of the Dense expert is computed as follows:

where

and

are the weight matrices of the first and second layers, respectively,

and

are the corresponding bias vectors, and

denotes a non-linear activation function such as ReLU.

3.3.2. Convolutional Neural Network

The CNN expert is designed to capture spatial characteristics inherent in network traffic data. It uses convolutional operations to detect local dependencies and spatial patterns, which are critical for identifying byte-level bursts and the structural similarities common to specific application layer protocols. The spatial feature vector is , which is derived from the raw input sample and typically includes representations such as byte histograms or two-dimensional packet matrices. These are reshaped to form an input tensor , where h and w denote the height and width of the 2D matrix.

The CNN expert applies a 2D convolutional layer followed by a non-linear activation (ReLU), and then flattens the output into a feature vector for further processing. The overall transformation can be expressed as follows:

where

denotes the trainable parameters of the convolutional layer.

3.3.3. GRU Expert

The GRU expert is designed to capture statistical patterns in the traffic data over time. It processes the statistical feature vector

extracted from the input sample

, which includes sequential attributes such as packet lengths and inter-arrival intervals. These features are modeled as a time series:

The GRU cell operates on this sequence using the following set of equations:

Here, and are the update and reset gates, respectively. is the candidate activation and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

The final hidden state

summarizes the learned temporal representation:

3.3.4. Convolutional Autoencoder

The Convolutional Autoencoder expert is designed to extract frequency-domain features

, typically obtained by applying a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on raw traffic sequences

. The CAE encodes these features into a latent representation

via the encoder network, and then reconstructs them through a decoder to produce

. This process captures both discriminative and reconstructive patterns in frequency space. The encoding and decoding operations are defined as follows:

where

and

are the weight matrices and bias vectors of the encoder and decoder, respectively, and

denotes a non-linear activation function (ReLU). The CAE is trained using a composite loss function that integrates classification accuracy, reconstruction fidelity, and regularization:

where

is the cross-entropy loss for classification, the second term is the mean squared reconstruction error, and the final term represents the L2 regularization on the CAE parameters

. The hyperparameters

are regularization coefficients.

3.3.5. Long Short-Term Memory Expert

The LSTM expert is specifically designed to extract temporal sequences , where each represents a time-ordered feature vector (e.g., packet inter-arrival times or session timelines). The LSTM unit effectively captures long-range dependencies and periodic behaviors in IoT traffic.

Each LSTM cell operates through a sequence of gating mechanisms:

Here, denotes the sigmoid activation, is the hyperbolic tangent function, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication. The matrices and bias vectors are learnable parameters of the LSTM.

Finally, the output of the LSTM expert for sample

i is the final hidden state after

T time steps:

This latent vector encodes temporal dynamics critical for detecting complex and stealthy patterns in application layer flows.

Each expert model processes its respective input features and produces a class probability distribution using a softmax activation function. This enables each expert to independently assess the likelihood of the input belonging to each target class. The softmax output reflects the expert’s confidence based on the type of features it specializes in, such as statistical, spatial, or temporal patterns. The ALF module later integrates these individual probability distributions to generate the final classification decision.

Each expert model

produces a class probability distribution:

where

is the feature extractor function of expert

k, parameterized by

, and

and

are the parameters of the classification head.

Each expert’s classification loss is calculated using categorical cross-entropy as follows:

These domain-specialized predictions will later be dynamically weighted and fused through the proposed Attentive Learnable Fusion (ALF) module to form the final output.

3.4. Gating Network

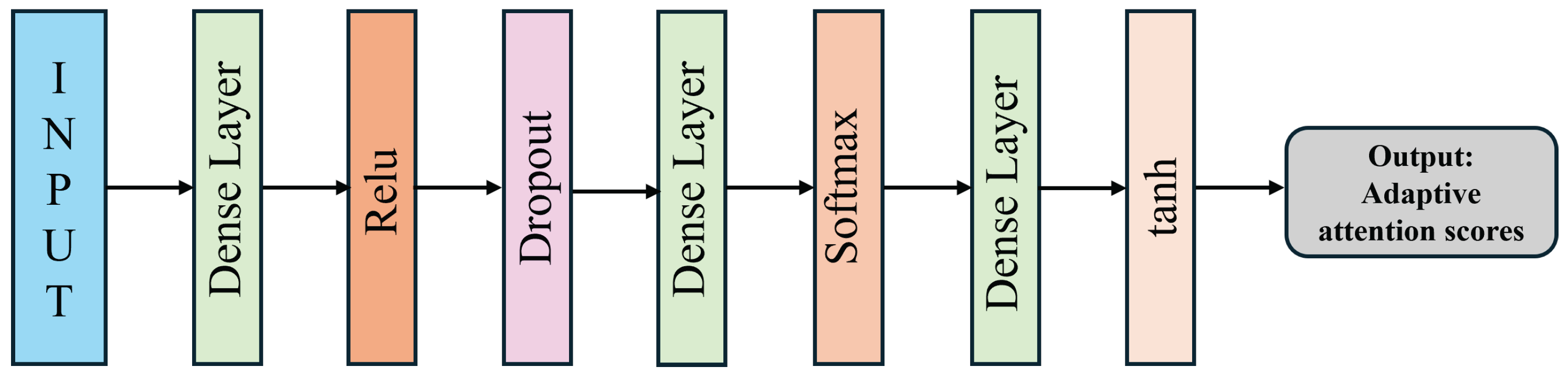

To enable adaptive expert selection, the proposed ALF-MoE model incorporates a dynamic gating network that computes context-aware confidence scores for each specialized expert. The proposed Gating Network with Attention Refinement is shown in

Figure 2. The gating network is a deep multilayer architecture that computes dynamic, context-aware expert weights for the MoE model. Initially, the raw input features are passed through a dense layer followed by a ReLU activation to capture non-linear patterns. A dropout layer is employed next to mitigate overfitting and promote generalization. Given an input instance

, the gating network

computes a raw score vector

, where each score

reflects the contribution confidence of the corresponding expert

. The output is then fed into another dense layer with a softmax activation, producing normalized weights indicating the importance of each expert network.

This ensures that the sum of weights across all experts is 1.

To further enhance the selectivity and contextual awareness of the expert weighting, the softmax-normalized outputs are refined via an attention-based transformation using an additional dense layer followed by a tanh activation, resulting in adaptive attention scores. Each expert’s attention weight

is computed using a learnable linear transformation of the raw score

:

where

and

are the parameters of the attention projection layer.

This mechanism enables the gating network not only to reflect the relative confidence in each expert but also to adaptively focus on the most relevant predictors depending on the input characteristics. The resulting attention weights are then passed to the ALF fusion module for final decision aggregation. This design improves the model’s ability to balance contributions from multiple feature domains, thus enhancing classification robustness and accuracy in diverse traffic scenarios.

3.5. Fusion Strategy in ALF-MoE

The Attention-based Learnable Fusion (ALF) module in the proposed ALF-MoE architecture is designed to effectively integrate the outputs from multiple specialized expert networks into a robust final classification decision. The individual expert predictions and the gating network’s attention scores are aggregated via a weighted summation, with each expert’s output scaled by its corresponding attention weight to produce a unified, context-aware representation. The aggregated prediction vector obtained from the mixture of expert networks is calculated as follows:

where

is the latent fused representation.

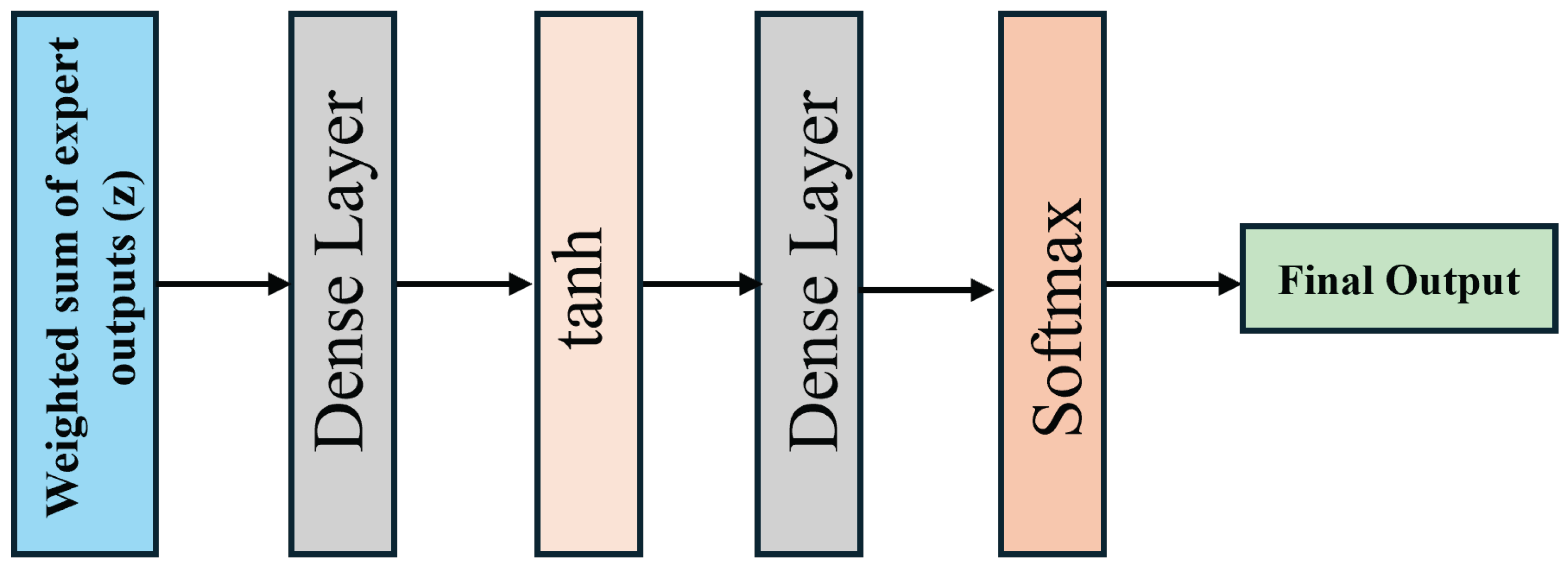

The architecture of the ALF module is shown in

Figure 3. The aggregated vector

is first passed through a fully connected dense layer to capture high-level interactions between the expert outputs. A tanh activation function follows, introducing non-linearity and enabling the network to model complex relationships across expert domains. A second dense layer then processes the transformed representation to project it back into the class space. Finally, a softmax activation function is applied to produce a normalized probability distribution over the classes.

where

and

are trainable parameters of the final classification layer. The use of tanh introduces non-linear dependencies among expert outputs, enabling the model to resolve ambiguous input cases and adapt to heterogeneous traffic patterns with enhanced accuracy. This layered transformation pipeline ensures that the fusion process is both adaptive and learnable, enabling the model to dynamically recalibrate the contribution of each expert prediction based on the context of the input sample, ultimately improving classification robustness and accuracy. The details of the ALF-MoE training process is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 ALF-MoE: Attention-Based Learnable Fusion of Specialized Mixture of Expert Networks |

Require: Input instance

Ensure: Predicted class label

for Each expert model {Dense, CNN, GRU, CAE, and LSTM} do

Extract domain-specific feature vector from input

Compute expert prediction

end for

Pass to the Gating Network;

Compute attention logits for each expert

Normalize the attention scores with softmax:

;

Compute fused prediction:

Pass z through the Learnable Fusion Layer:

return

|

4. Experiment and Performance Evaluation

This section presents the experimental evaluation conducted on two publicly available datasets to benchmark the proposed ALF-MoE framework against several state-of-the-art models. The experiments are designed to comprehensively assess the framework’s classification accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability across diverse network traffic scenarios.

4.1. Dataset Description

We assessed the effectiveness of the proposed traffic classification framework using two widely adopted IoT benchmark datasets: ISCX VPN-nonVPN [

52] and Unicauca [

53]. These datasets encompass a diverse range of IoT network traffic categories, capturing both encrypted and unencrypted communication patterns. Their comprehensive coverage of application-level behaviors enables a robust and reliable evaluation of the model’s ability to accurately classify complex IoT traffic scenarios.

4.1.1. ISCX VPN-NonVPN Dataset

The ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset [

52], developed by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity at the University of New Brunswick, remains a respected basis for research regarding classification tasks for encrypted and VPN traffic. This dataset simulates real user behavior using two personas: Alice and Bob. This ranges from simple browsing to such tasks as sending emails, streaming videos, instant messaging, transferring files, voice over IP communications, and peer-to-peer transactions. This data is measured in a typical network environment as well as a network with VPN encryption. The types of traffic included come from common uses such as Skype, YouTube, Facebook, and BitTorrent. All this data breaks down primarily into several major types: VOIP, VPN-VOIP, P2P, and VPN-P2P.

4.1.2. Unicauca Dataset

This dataset is a large-scale and realistic network traffic dataset collected by Universidad del Cauca, Colombia [

53]. It was collected using packet capturing processes that were performed at different points in time: in the morning and afternoon periods. All this data was collected for several days distributed throughout April and June 2019. This resulted in a total of 2,704,839 flow records with 50 flow-level features expressed in a CSV format. Among these features are source and destination IP addresses and ports. Additionally, other general properties comprise the duration of flows, interarrival time for flows, sizes for data packets, and Layer 7 protocols. All of these elements establish ground truth classifications. The wide time span for data collection along with the wide coverage of application protocols makes this dataset a realistic representation of traffic conditions.

4.1.3. UNSW-IoTraffic Dataset

The UNSW-IoTraffic dataset [

54] was developed primarily at the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney), Australia. The dataset contains real-world IoT communications captured over an extended period. The dataset is released in three complementary components: (i) raw network packet traces with full headers and payloads, (ii) flow-level metadata that summarizes fine-grained bidirectional communication behaviors, and (iii) protocol parameters that describe network protocol characteristics. In addition, the dataset provides protocol data models for six dominant protocols: TLS, HTTP, DNS, DHCP, SSDP, and NTP. The capture includes 95.5 million packets collected over 203 days. The raw packet traces are organized into 27 per-device packet capture (PCAP) files, reflecting device-specific traffic behavior.

4.2. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance of the proposed ALF-MoE framework, experiments were conducted on two publicly available datasets: ISCX VPN-nonVPN and Unicauca. The datasets were partitioned into 70% for training, 10% for validation, and 20% for testing. The validation subset was used for hyperparameter tuning. Training was performed over 50 epochs using ten-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness and mitigate bias. The model was optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 64. To reduce overfitting and ensure stable convergence, L2 regularization was applied. All models were implemented in Python 3.9.25 utilizing TensorFlow and Keras libraries. The experiments were executed on a system equipped with a 12th-generation Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12600K CPU operating at 3.69 GHz, 48 GB RAM, running Ubuntu 20.04.4 LTS with Linux kernel version 5.13. Data processing and visualization were performed using the NumPy 2.0.2, Pandas 2.3.3, Matplotlib 3.9.2, and Seaborn 0.13.2 libraries.

4.3. Training Details

To validate the robustness of the proposed ALF-MoE model, the class labels were encoded using LabelEncoder and converted to one-hot vectors. All input features were normalized using StandardScaler fitted on the training data only, and the same scaling parameters were applied to the validation and test splits. The normalized feature vector was then deterministically transformed into five domain-specific inputs: general, spatial, statistical, frequency, and temporal. These inputs were reshaped to match the expert formats, i.e., for the Dense expert, for the CNN expert, for the GRU expert, for the CAE expert, and for the LSTM expert. A fixed random seed (random_state = 42) was used for data splitting to ensure consistent results. The model parameters were optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of , , , and . The model was trained by minimizing the categorical cross-entropy loss. Dropout with a rate of 0.3 was applied in the expert networks and gating layers to reduce overfitting. For expert fusion, all expert outputs were projected to a common latent dimension of 64 before being weighted by the gating network and aggregated. Training was performed for a maximum of 50 epochs using a batch size of 32, and a held-out validation set was used to monitor convergence.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we utilize standard evaluation metrics commonly adopted in machine learning. In particular, we compute overall accuracy, precision, and recall to assess how accurately the model classifies traffic flows into their corresponding categories.

Accuracy: The proportion of total correct predictions to the total number of predictions made.

Precision: The proportion of correctly predicted positive observations to the total predicted positives.

Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positive cases that were correctly identified.

F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balance between the two.

After the classification process, correctly identified samples of a particular class are recorded as True Positives (TP). In contrast, correctly classified instances of all other classes are treated as True Negatives (TN). Conversely, misclassified samples are recorded as either False Positives (FP) or False Negatives (FN), depending on whether their predicted and actual class labels match.

4.5. Performance Analysis of ALF-MoE

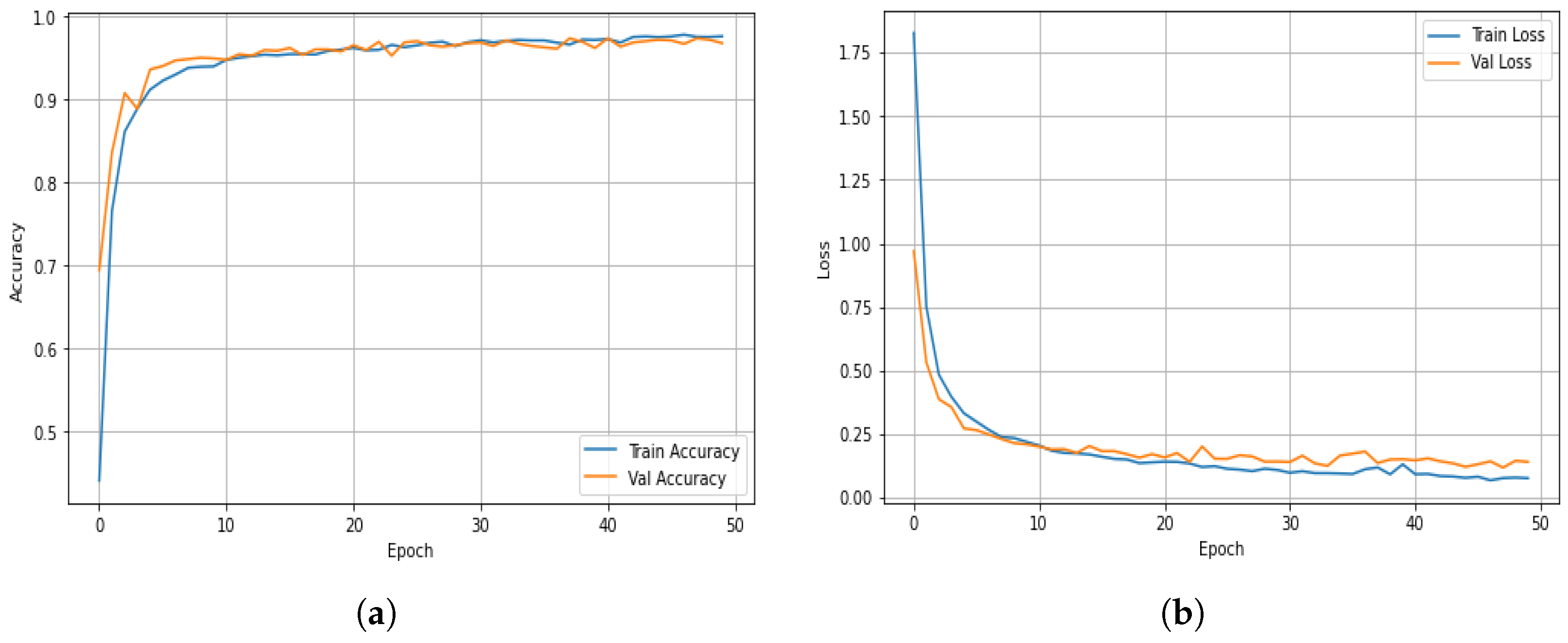

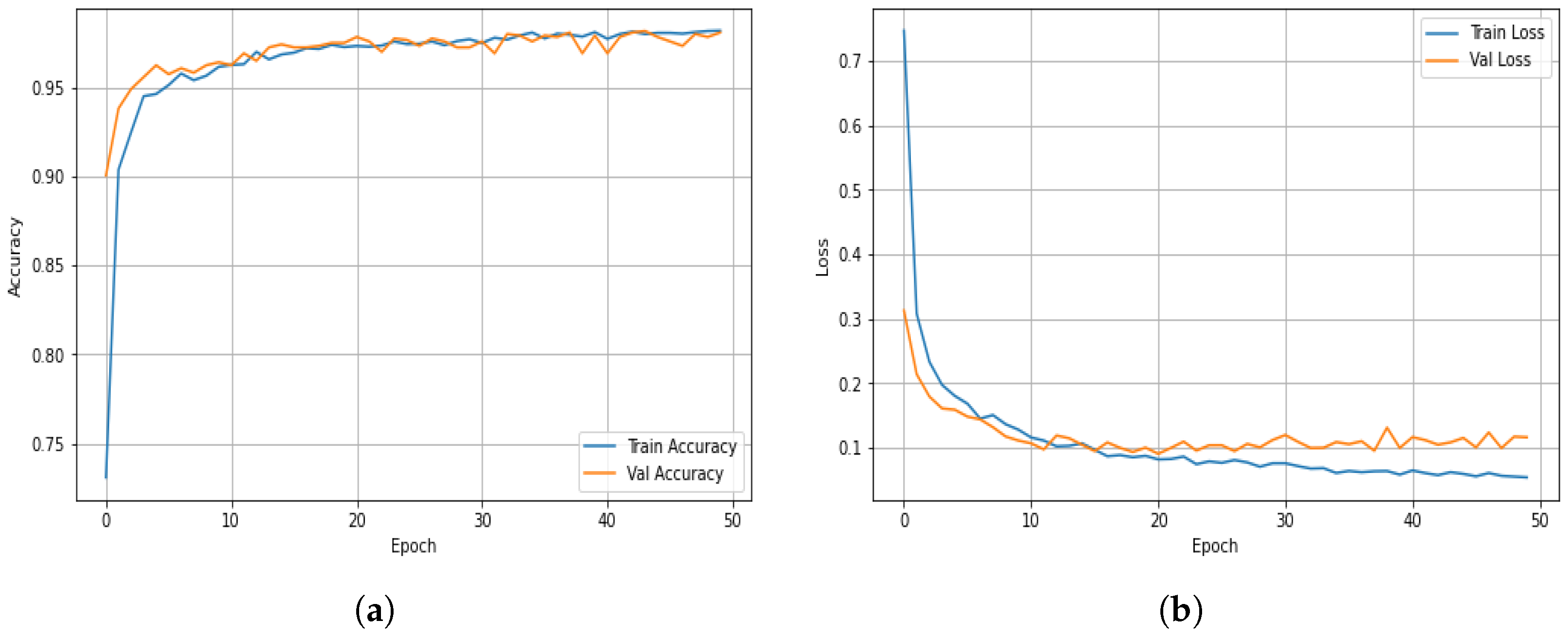

Figure 4 illustrates the overall training behavior of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset.

Figure 4a presents the training and validation accuracy curves of the proposed ALF-MoE model over 50 epochs on the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset. The model exhibits rapid convergence within the first ten epochs, followed by a plateau, indicating that the learning process has stabilized. Notably, the alignment between training and validation accuracy remains consistently close throughout the training period, demonstrating minimal divergence. This close correspondence is a strong indicator of the model’s generalization capability and suggests that overfitting is effectively mitigated. The high and stable validation accuracy further substantiates the efficacy of the learned gating mechanism and the integrated regularized loss function, both of which contribute to balanced expert selection and robust model performance. The convergence behavior confirms that the ALF-MoE architecture successfully harmonizes learning and specialization without compromising accuracy.

Figure 4b presents the training and validation loss curves over 50 epochs on the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset. At the beginning of training, the loss drops quickly, showing that the model is learning well from the start. This rapid improvement is due to the combination of a standard loss function (categorical cross-entropy) and an additional term that encourages all expert models to contribute evenly. After about ten training rounds (epochs), both the training and validation losses stabilize and decrease smoothly, indicating that the model is learning steadily without sudden jumps or instability. This is important because many MoE models can become unstable if certain experts dominate. The smooth loss curves indicate that the training process is well controlled, and the learning rate and optimizer are working effectively.

The overall learning behavior of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the Unicauca dataset is depicted in

Figure 5. The overall learning behavior of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the Unicauca dataset, depicted in

Figure 5a, shows how the training and validation accuracy of the ALF-MoE model changes over 50 training rounds using the Unicauca dataset. The model quickly improves over the first ten epochs and then stabilizes, indicating it has learned well. The accuracy for both training and validation remains close, indicating that the model is not overfitting and performs well on new data. The strong, stable validation accuracy also shows that the gating network and regularized loss are working effectively, selecting the right experts during training and helping the model remain consistent.

The overall learning behavior of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the Unicauca dataset, depicted in

Figure 5b, shows how the training and validation loss values change over time for the ALF-MoE model on the Unicauca dataset. At the beginning of training, the loss drops quickly, indicating the model is learning effectively. This fast learning is due to the combination of standard loss (categorical cross-entropy) and an extra term that encourages all experts to be used fairly. After around ten epochs, the loss curves become stable and smooth, with no sudden jumps or drops. This stable trend indicates that the model is training reliably, which is important for ensemble models, which can sometimes become unstable when one expert dominates. The steady behavior indicates that the learning rate and optimizer are correctly set, helping the model learn efficiently.

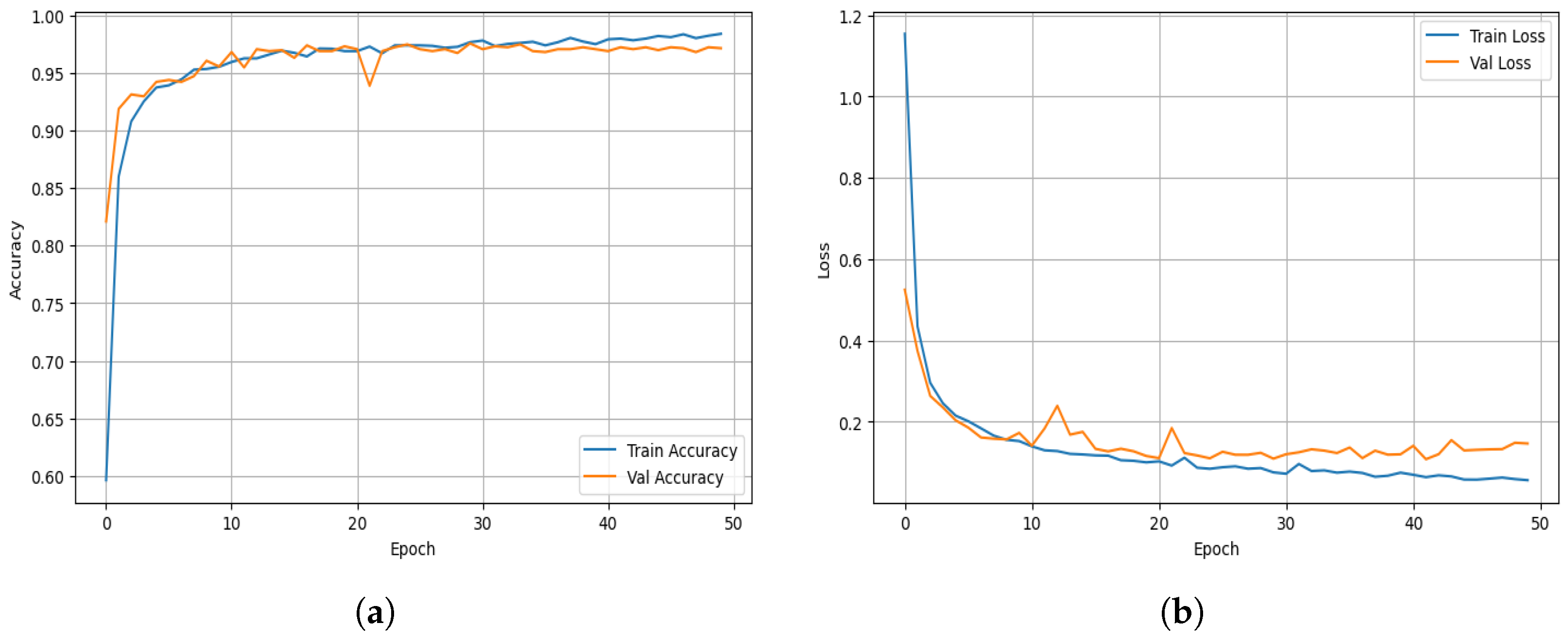

The overall learning behavior of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6a illustrates the training and validation accuracy over 50 epochs. The model improves rapidly during the first few epochs and reaches a high-accuracy region early in training. The training and validation accuracy remain close throughout, which indicates good generalization and limited overfitting. This stable validation trend suggests that the gating network is learning consistent expert weights and that the regularization settings help maintain robust performance on unseen samples.

Figure 6b presents the corresponding training and validation loss curves for the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset. The loss decreases sharply at the beginning, showing that the model learns discriminative patterns quickly. After the initial drop, both curves flatten and remain steady, which indicates convergence and stable optimization. The validation loss stays close to the training loss, with small variations across epochs. This behavior is desirable for an ensemble MoE model, where unstable expert selection can sometimes cause oscillations.

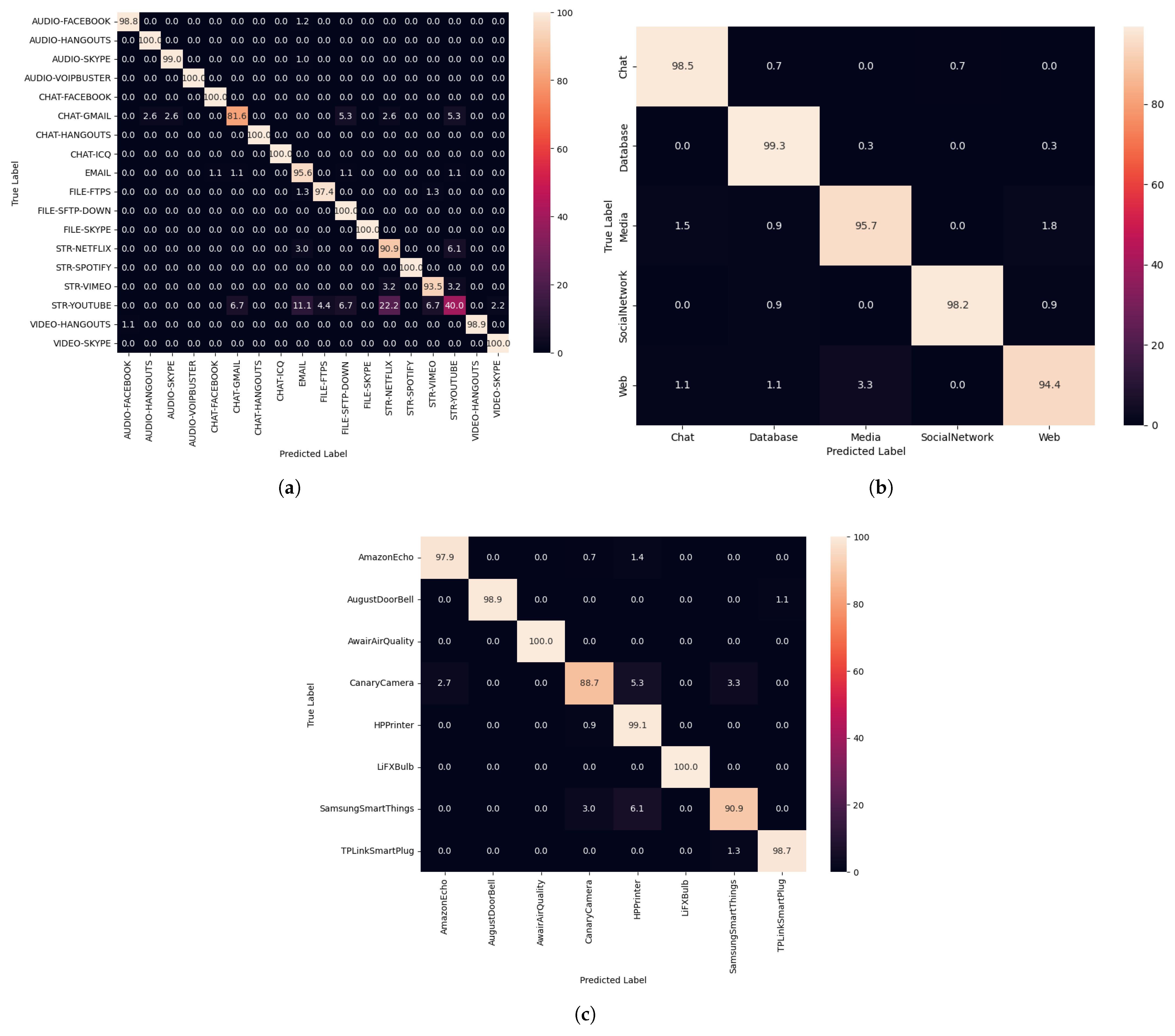

Figure 7 presents the normalized confusion matrices of the proposed ALF-MoE model on three datasets: (a) ISCX VPN-nonVPN, (b) Unicauca, and (c) UNSW-IoTraffic. In

Figure 7a, the ISCX VPN-nonVPN results show strong classification across all 18 classes, with most samples concentrated along the diagonal. The remaining off-diagonal values are small and mainly appear between classes with similar traffic characteristics, such as STR-YOUTUBE and STR-NETFLIX, and among CHAT-GMAIL, CHAT-HANGOUTS, and EMAIL. This pattern is expected because these applications share overlapping protocol behavior and statistical properties. Overall, the low off-diagonal percentages indicate that ALF-MoE maintains high class separability even in fine-grained multi-class settings.

Figure 7b shows the normalized confusion matrix for the Unicauca dataset, which contains five coarse-grained application categories. The matrix is nearly perfectly diagonal, indicating consistently high recall for all categories and minimal confusion. The clearer separation is expected due to the reduced number of classes and higher-level labeling, which lowers the ambiguity between categories.

Figure 7c reports the normalized confusion matrix for the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset using the selected IoT device classes. The diagonal dominance confirms that ALF-MoE can distinguish device-level traffic patterns effectively. The small off-diagonal entries occur mainly among devices with similar communication behaviors and shared protocol usage, which can produce comparable flow signatures. Despite this, the overall diagonal structure remains strong, indicating reliable generalization to IoT-specific traffic.

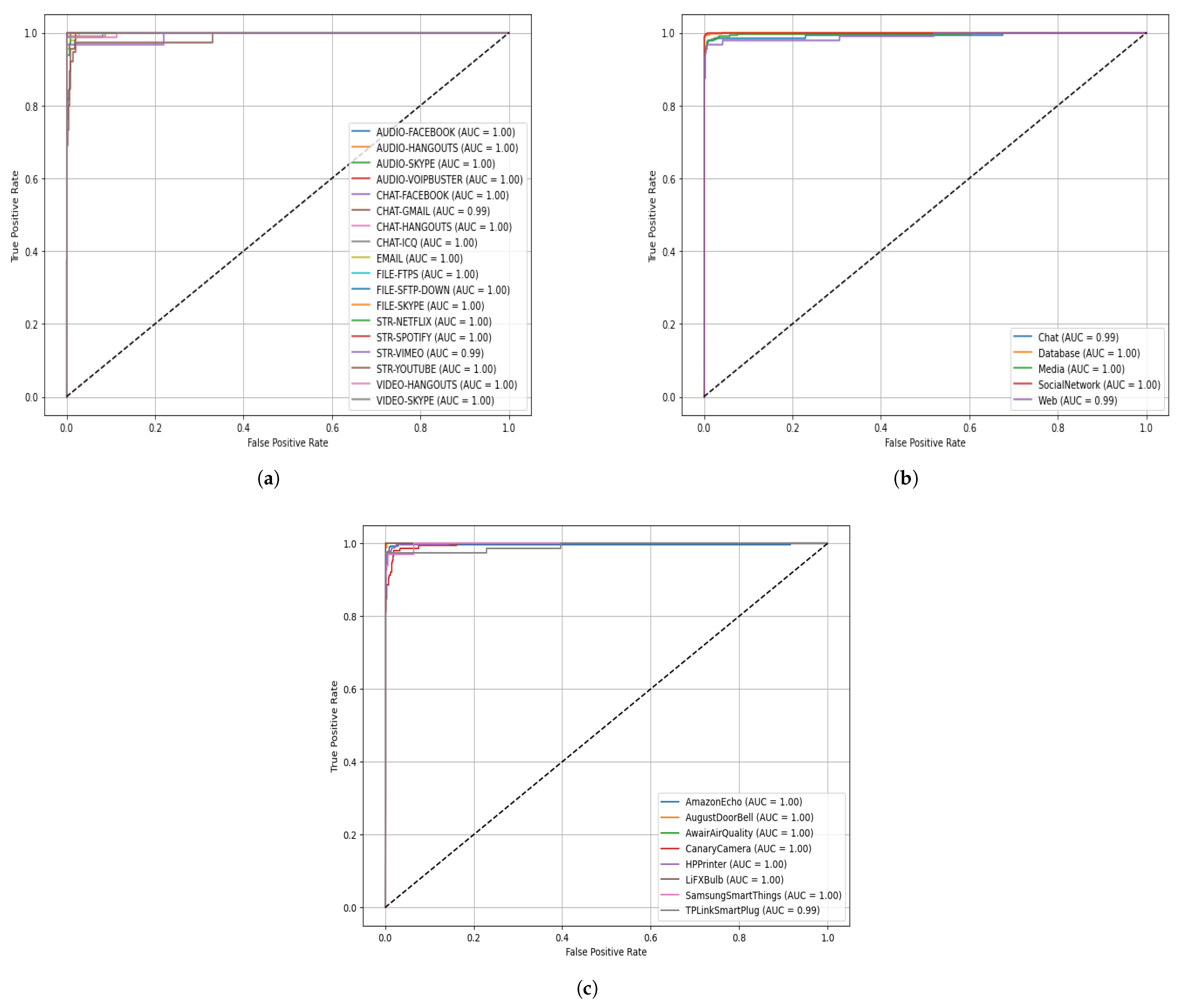

Figure 8 evaluates the classification capability of the ALF-MoE model using ROC-AUC curves across three datasets. In

Figure 8a, which presents the results for the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, the ROC curves for nearly all classes are tightly clustered near the top left corner of the graph, indicating near-perfect true positive rates with very low false positive rates. The AUC values for most classes approach 1.00, demonstrating that the model achieves excellent separability across diverse traffic classes, including encrypted and non-encrypted flows. A few classes, such as STR-YOUTUBE and STR-NETFLIX, show slightly lower AUCs (e.g., 0.89 and 0.93), likely due to overlapping traffic patterns or smaller class distributions, but overall the model achieves robust multi-class discrimination. In

Figure 8b, the ROC-AUC curves for the Unicauca dataset reflect similar high classification performance. The AUC for most categories, such as Database, Media, and SocialNetwork, reaches 1.00, indicating perfect classification. The Web class yields an AUC of 0.949, which, although slightly lower, still reflects strong performance. The Chat class shows a lower AUC of 0.969, possibly due to its overlap with other categories in terms of flow-level features. Overall, the model’s performance remains consistent across datasets with varying granularity and class definitions, underlining the generalization capability of the ALF-MoE architecture and its ability to maintain high discrimination across both fine-grained and coarse-grained traffic classifications. In

Figure 8c, the ROC-AUC curves for the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset indicate consistently strong discrimination across the selected IoT device classes. Most devices achieve an AUC close to 1.00, such as AmazonEcho, AugustDoorBell, AwairAirQuality, CanaryCamera, HPPrinter, LiFXBulb, and SamsungSmartThings, which suggests near-perfect separability in terms of their traffic patterns. TPLinkSmartPlug records a slightly lower AUC, but it still reflects excellent classification capability. The tight clustering of the ROC curves near the top left corner further confirms the model’s robustness on device-level IoT traffic, where many devices share common protocols and background communication behaviors.

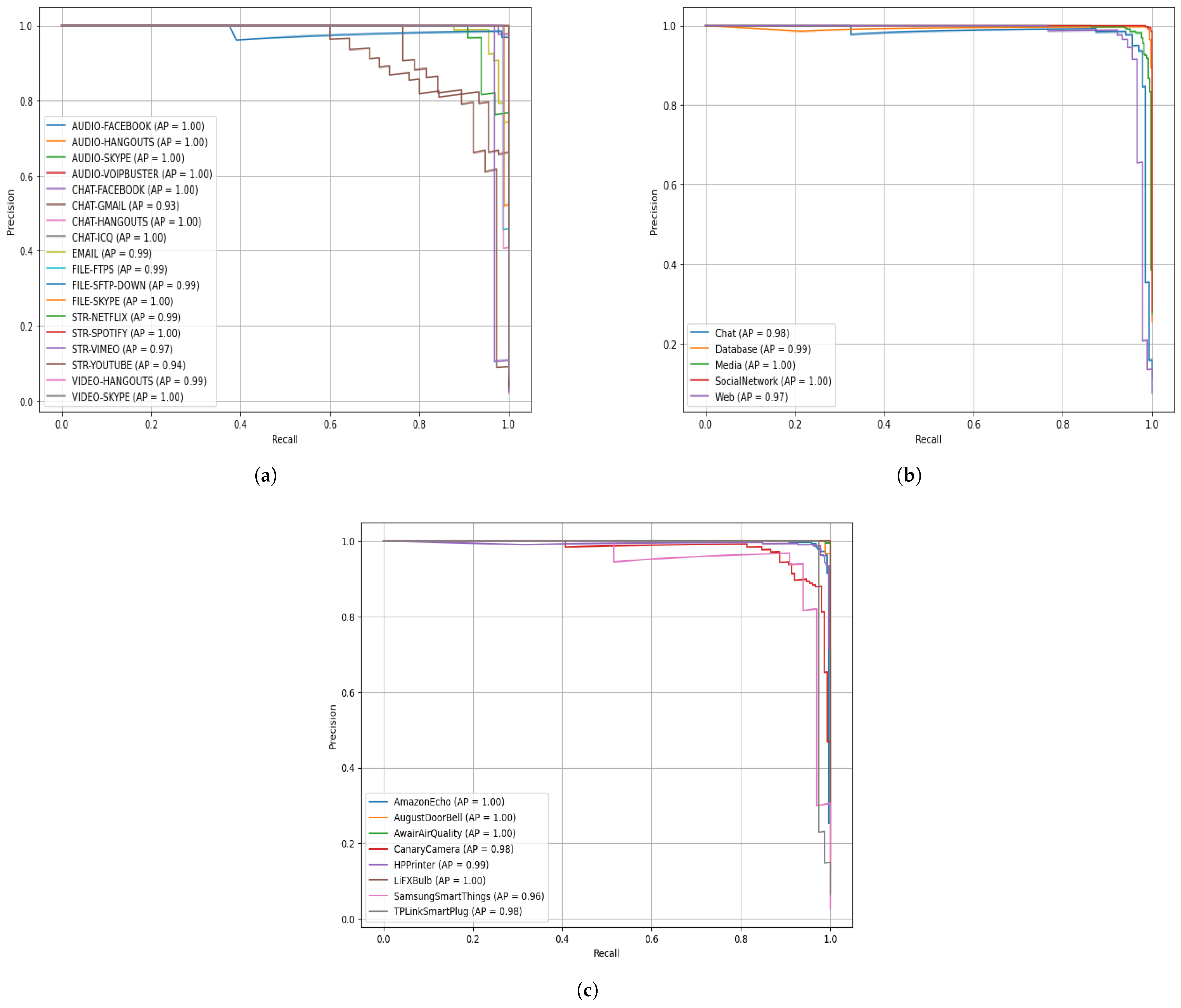

Figure 9 shows the precision–recall (PR) curves for the proposed ALF-MoE model evaluated on three datasets: the (a) ISCX VPN-nonVPN, (b) Unicauca, and (c) UNSW-IoTraffic dataset. Each curve represents how well the model balances precision (correct predictions among predicted positives) and recall (correct predictions among actual positives) for different classes. On the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, most classes show near-perfect precision and recall, as evidenced by curves near the top right corner, with the Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores close to 1.00, indicating excellent classification performance across diverse encrypted traffic types. For the Unicauca dataset, the PR curves are also tightly grouped toward the upper right, reflecting strong performance and minimal class confusion. The average precision values confirm that the model maintains high accuracy across all classes. This illustrates the model’s ability to generalize across datasets with varying traffic and application types. For the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset, the PR curves also demonstrate strong device-level discrimination. Several device classes achieve an average precision (AP) of 1.00, indicating highly reliable detection across thresholds. A few classes show slightly lower AP values, such as CanaryCamera (AP ≈ 0.90), SamsungSmartThings (AP ≈ 0.96), and TPLinkSmartPlug (AP ≈ 0.98), which suggests mild overlap in traffic behavior among certain IoT devices.

Table 3 presents a detailed per-class performance evaluation of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, highlighting its ability to distinguish among 20 diverse application traffic categories effectively. The model achieves perfect classification performance (100% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) across several categories, including AUDIO-FACEBOOK, AUDIO-SKYPE, AUDIO-VOIPBUSTER, CHAT-HANGOUTS, STR-SPOTIFY, and VIDEO-SKYPE. This indicates the model’s strong ability to extract discriminative features and leverage expert specialization for clearly separable traffic patterns. However, certain classes, such as CHAT-GMAIL and STR-YOUTUBE, show comparatively lower performance, with accuracy values of 76.31% and 77.78%, and F1-scores of 0.83 and 0.81, respectively. This performance drop may stem from overlapping behavioral characteristics shared with other chat and streaming applications, which introduce classification ambiguity. Despite this, the model maintains relatively balanced precision and recall values across all classes, reflecting its robustness in handling both false positives and false negatives.

Table 4 summarizes the classification performance of the ALF-MoE model on the Unicauca dataset, which features five high-level application categories: Chat, Database, Media, SocialNetwork, and Web. The model achieves strong performance across all classes, with accuracy ranging from 93.3% (Web) to 99.4% (SocialNetwork). The associated precision, recall, and F1-score values consistently exceed 0.96, underscoring the model’s ability to generalize effectively in a coarse-grained classification scenario. The class Chat shows a slightly lower recall value (0.96), potentially due to misclassifications with similar communication-oriented categories. Nonetheless, the high precision value (0.96) and F1-score (0.96) confirm that the model minimizes both over-predictions and under-predictions. Notably, the model achieves perfect precision, recall, and F1-score (1.00) for the SocialNetwork class, indicating excellent expert specialization for this traffic type.

Table 5 reports the per-class performance of the proposed ALF-MoE model on the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset, which contains IoT device-level classes. The model shows consistently strong results across all devices, with the class-wise accuracy ranging from 91.86% (CanaryCamera) to 100.00% (LiFXBulb). Most classes achieve an accuracy above 96%, indicating the reliable discrimination of device-specific traffic patterns. In terms of precision, recall, and F1-score, the model maintains high values for the majority of devices, confirming balanced detection performance. LiFXBulb achieves perfect precision, recall, and F1-score (1.00), demonstrating clear separability for this device’s traffic. AugustDoorBell also shows near-ideal performance with a precision value of 1.00, a recall value of 0.99, and an F1-score of 0.99. The lowest-performing class is CanaryCamera, with a precision value of 0.93, recall of 0.91, and F1-score of 0.92, due to traffic similarity with other smart home devices that share common protocols and background communication behaviors. SamsungSmartThings shows a comparatively lower precision value (0.84) and F1-score (0.89), suggesting occasional false positives, but its recall remains high (0.94), indicating that most true samples are still correctly identified.

4.6. Gating Behavior and Expert Utilization Analysis

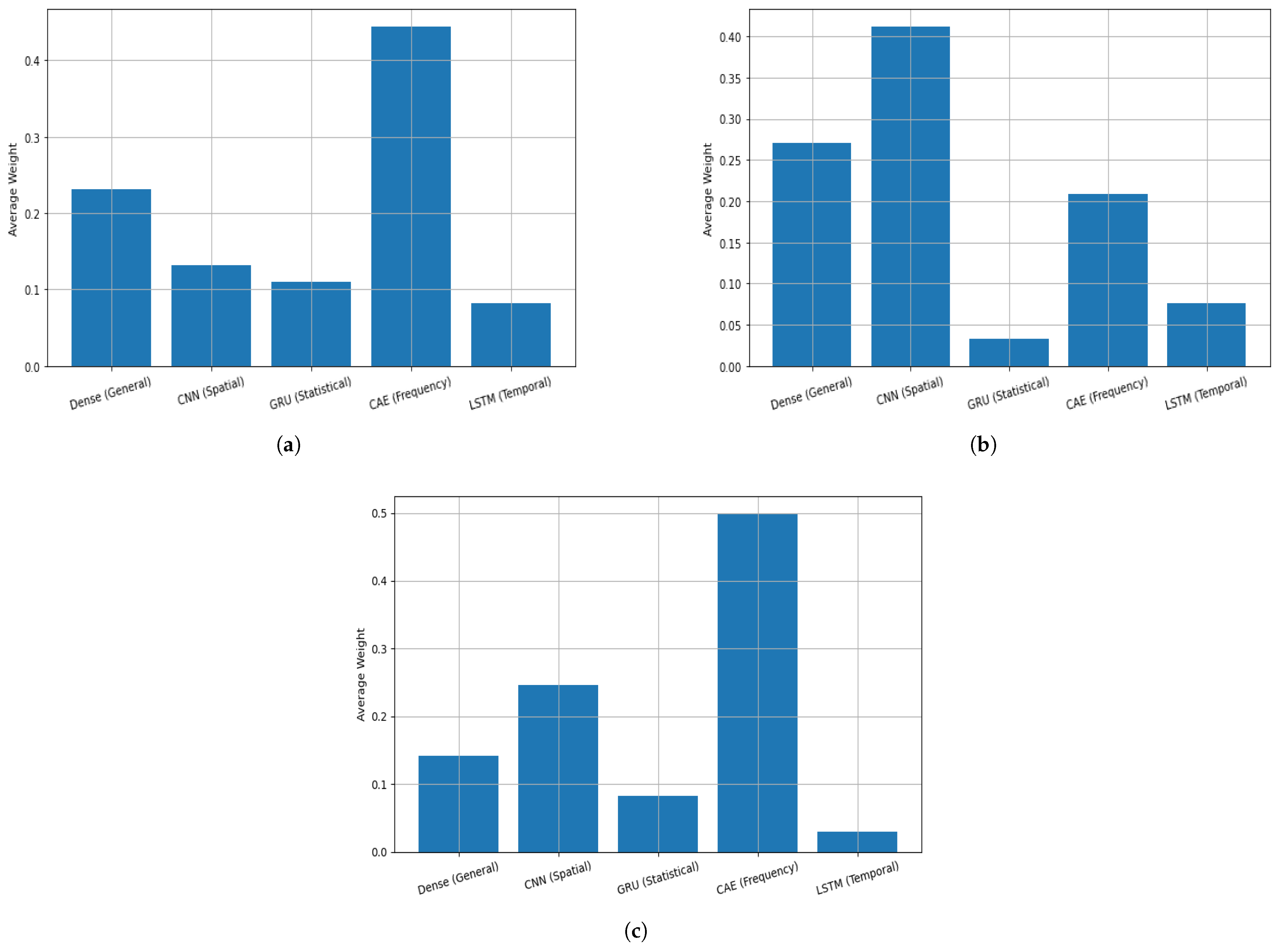

Figure 10 provides a detailed comparison of the average gating weights assigned to each expert module in the proposed ALF-MoE architecture across three datasets: ISCX VPN-nonVPN (

Figure 10a), Unicauca (

Figure 10b), and UNSW-IoTraffic (

Figure 10c). The distribution of weights reflects the relative importance of each expert model (DNN, CNN, GRU, CAE, and LSTM) as determined by the learned gating mechanism. In the ISCX dataset, the CAE (frequentist) expert received the highest average weight (0.44), indicating its strong ability to extract distinguishing features from ISCX traffic flows, likely due to its unsupervised reconstruction of high-dimensional inputs. The general-purpose DNN expert also played a significant role (0.22), while LSTM (temporal expert) received the lowest weight, suggesting that temporal dependencies were less critical for this dataset. Conversely, in the Unicauca dataset, the CNN (spatial expert) emerged as the dominant contributor (0.40), closely followed by the general DNN (0.26) and CAE (0.22). This shift in expert importance suggests that local spatial patterns and hierarchical abstractions, which CNNs are particularly effective at capturing, are more discriminative in Unicauca’s application-level flow classes. The GRU (sequential) expert received minimal weight, indicating limited sequential dependencies in the Unicauca feature space. These observations highlight the adaptive nature of the ALF-MoE gating network, which dynamically allocates attention based on the dataset’s characteristics, thereby ensuring optimal expert collaboration tailored to the specific traffic patterns and feature relevance of each scenario. In UNSW-IoTraffic, the CAE (frequency expert) receives the highest average weight (0.50), showing that frequency-domain representations provide the most discriminative cues for separating device-specific behaviors. This is reasonable for IoT traffic, where periodic signaling, heartbeat messages, and repetitive communication patterns are standard and are well captured in the spectral domain. The CNN (spatial expert) contributes the second-largest weight (around 0.25), suggesting that local feature interactions and structured patterns in the constructed spatial input are also important for device identification. The Dense expert shows a moderate contribution (0.15), indicating that global flow statistics still support classification but are not the primary drivers in this dataset. In contrast, the sequential GRU expert and the temporal LSTM expert receive relatively small weights (0.10), implying that explicit temporal dependencies in the constructed sequences are less informative than frequency and local spatial patterns for UNSW-IoTraffic.

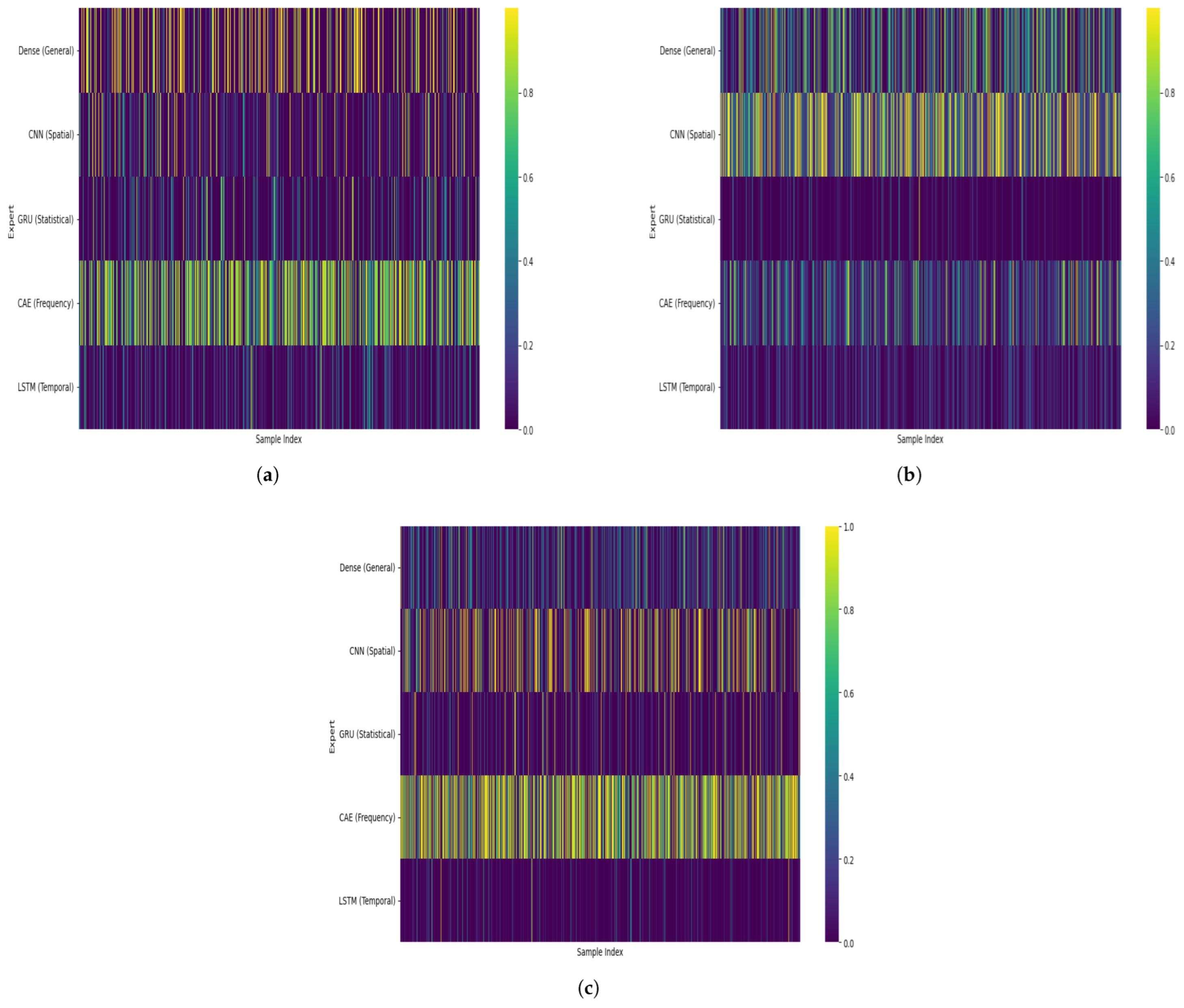

To complement the average gating weights for each expert,

Figure 11 visualizes the sample-wise gating weight distributions for each expert across validation samples. In both datasets, the gating network dynamically varies the weights per input instance, rather than assigning static importance to experts. This reflects the architecture’s adaptive nature. For the ISCX dataset (

Figure 11a), a broader spread in expert usage is visible, particularly for the dense and CAE modules, suggesting that the model frequently switches between representations depending on traffic type. In the Unicauca dataset (

Figure 11b), the CNN expert shows consistently strong activations across samples, reinforcing its dominant role. Meanwhile, the statistical expert receives minimal attention in both datasets, suggesting limited standalone utility but potentially serving a supporting role when combined with others. For the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset (

Figure 11c), the sample-wise gating heatmap shows clear, input-dependent expert selection across validation samples. The CAE exhibits the most frequent and strongest activations, with many samples receiving high weights, which aligns with its dominant average contribution on this dataset. This pattern indicates that frequency-domain cues are consistently informative for distinguishing IoT device behaviors, especially when devices generate periodic and repetitive communication traffic.

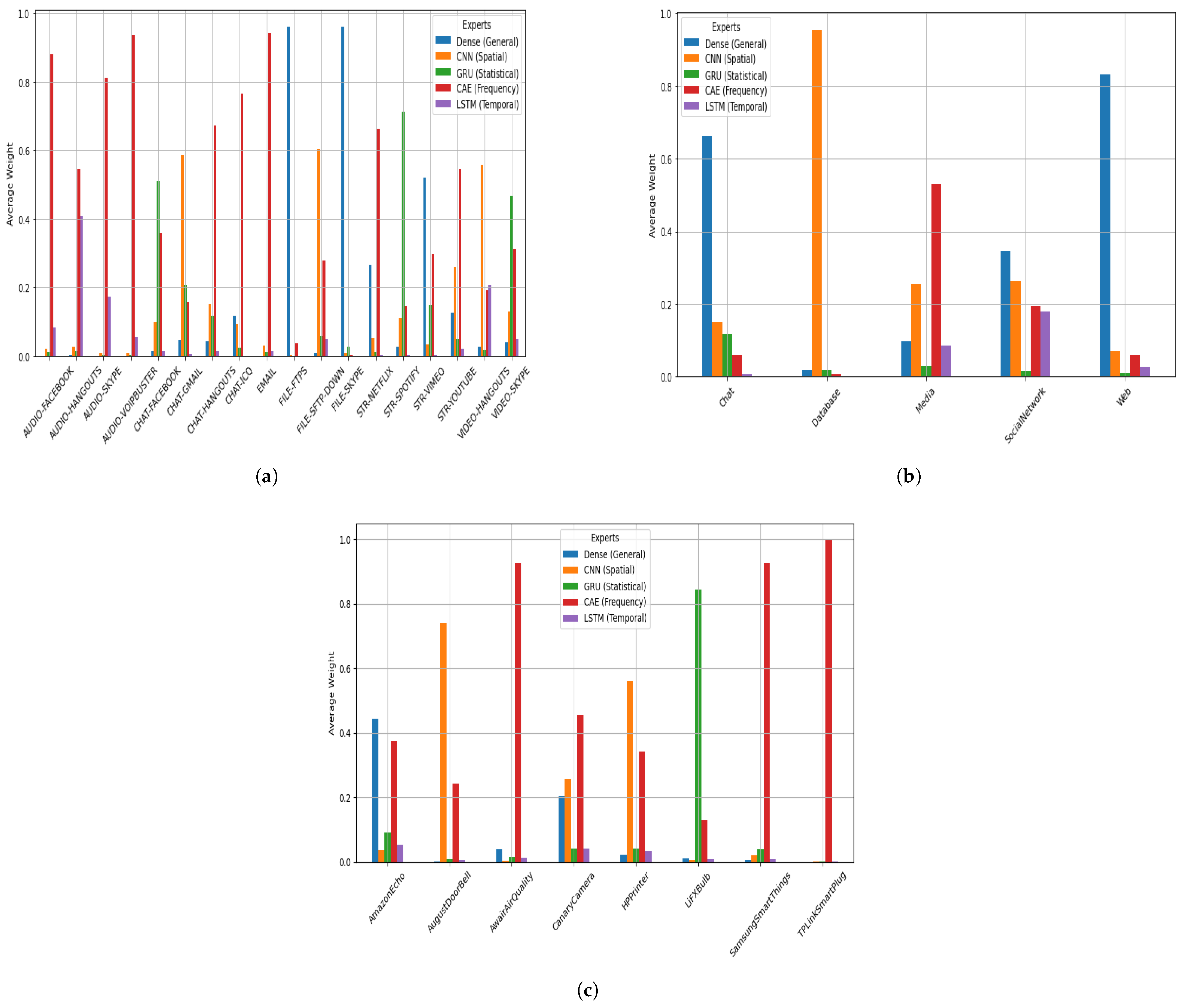

Figure 12 presents the average gating weights assigned to each expert based on the predicted class labels in the (a) ISCX VPN-nonVPN, (b) Unicauca, and (c) UNSW-IoTraffic datasets. These figures provide critical insight into the specialization behavior of the gating network in the ALF-MoE model. In the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset (

Figure 12a), it is observed that CNN (spatial) and CAE (frequentist) experts dominate across multiple classes, especially for traffic types with pronounced spatial or frequency-based characteristics, such as VIDEO-SKYPE, AUDIO-FACEBOOK, and STR-SPOTIFY. Meanwhile, the Dense (general) and LSTM (temporal) experts exhibit class-specific activations, particularly in sequential or mixed-type traffic such as FILE-FTP and CHAT-HANGOUTS, suggesting that the gating mechanism effectively allocates model capacity based on input modality. Similarly, in the Unicauca dataset (

Figure 12b), the gating network shows a distinct allocation pattern, with the CNN (spatial) expert receiving the highest weight for the Database and Media classes, suggesting a strong spatial dependency in these categories. In contrast, the Dense (general) expert is more involved in Chat and Web, reflecting their generalized content features. The GRU (statistical) expert shows minimal influence across both datasets, possibly due to redundancy or lower relevance of purely statistical patterns in these tasks. These findings validate the ALF-MoE model’s selective specialization strategy and emphasize its adaptability to structural differences across traffic categories, enabling robust, interpretable multi-expert learning. Moreover, in UNSW-IoTraffic (

Figure 12c), this class-wise breakdown provides deeper insight into how the gating network specializes expert usage for different device behaviors, rather than relying on a single fixed weighting strategy. Overall, the CAE (frequency) expert performs best across most device classes, indicating that frequency-domain cues are highly discriminative for device identification. In particular, AwairAirQuality, SamsungSmartThings, and TPLinkSmartPlug exhibit a strong CAE emphasis, suggesting that periodic signaling and repetitive communication patterns are key characteristics of these devices. However, the gating mechanism also reveals meaningful class-dependent variations. For AugustDoorBell and HPPrinter, the CNN (spatial) expert receives a comparatively high weight, indicating that local feature interactions in the constructed spatial input are particularly informative for these device traffic profiles. The Dense (general) expert makes a notable contribution to Amazon Echo, demonstrating the usefulness of global flow-level statistics for voice-assistant traffic. Interestingly, LiFXBulb shows firm reliance on the GRU (statistical) expert, suggesting that its constructed statistical representation contains distinctive patterns that the gating network exploits. The LSTM (temporal) expert remains consistently low across all classes, suggesting that long-range temporal dependencies, as modeled by the LSTM input format, contribute less to the UNSW-IoTraffic device classification task.

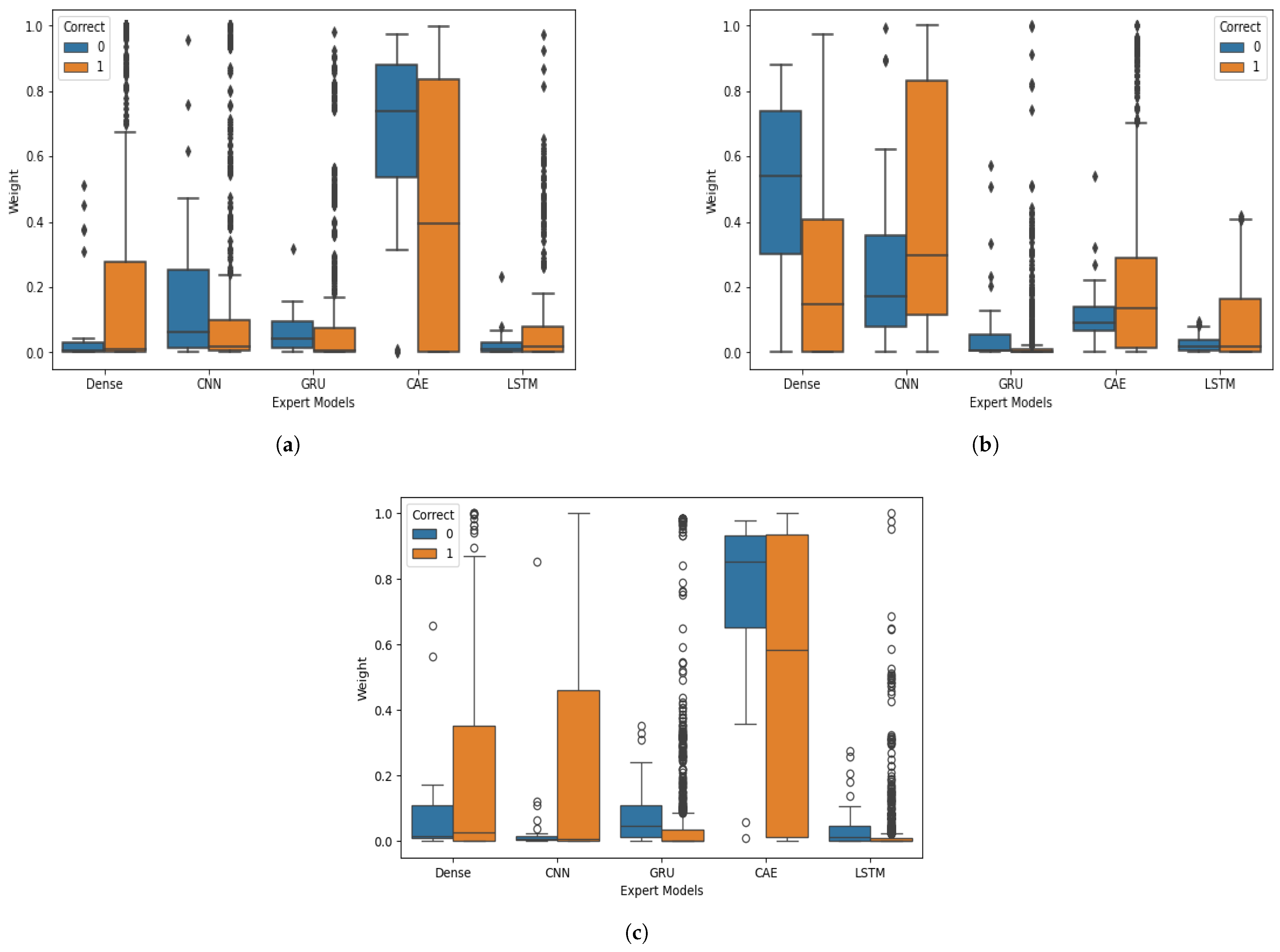

Figure 13 illustrates the distribution of gating weights assigned to individual experts by the gating network based on prediction correctness across various datasets: the (a) ISCX VPN-nonVPN, Unicauca, and UNSW-IoTraffic datasets. Each boxplot shows the degree of reliance the gating mechanism places on a particular expert when the final prediction is correct (label 1) versus incorrect (label 0). This analysis offers valuable insight into how different experts contribute to accurate vs. faulty decisions, highlighting the adaptive specialization mechanism of the ALF-MoE model. In the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset (

Figure 13a), the CAE (frequency-based) expert is most prominently favored in correct predictions, often receiving the highest weights when the model succeeds. The dense expert also maintains moderately strong weights for correct classifications. In contrast, the CNN and GRU experts are more evenly distributed across both correct and incorrect classifications, indicating greater generalizability. Moreover, LSTM contributes relatively low weights overall, suggesting that temporal dependencies are less critical for this dataset. A clear shift in weight distribution for the CAE expert between correct and incorrect predictions supports the claim that gating emphasizes specialized experts more when confident decisions are made. For the Unicauca dataset (

Figure 13b), the CNN expert dominates the correct classifications, consistently receiving the highest weights. This suggests that local spatial patterns are highly informative for traffic classes in this dataset. The dense and GRU experts show a more balanced contribution across both correct and incorrect predictions. The LSTM and CAE experts again appear to play a lesser role in accurate classification for this dataset. The relatively wider interquartile range for incorrect predictions suggests increased uncertainty in expert selection, reinforcing the benefit of the gating mechanism’s adaptivity to input-level patterns. As a result, the plots demonstrate that ALF-MoE not only balances expert contributions but also selectively amplifies the most informative expert based on the input context, leading to better generalization ability and reduced reliance on any single model. These dynamics affirm the benefit of incorporating an interpretable gating structure in expert-based ensemble architectures. For the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset (

Figure 13c), the CAE expert receives the largest weights overall, and its median weight is notably higher for correct predictions than for incorrect predictions. This indicates that the model is more likely to succeed when the gating network strongly emphasizes frequency-domain representations, which aligns with the periodic and protocol-driven nature of IoT device communications. The wider spread of CAE weights in incorrect cases suggests that misclassifications often occur when the gating distribution becomes less decisive or when frequency cues are less distinctive. The Dense expert shows relatively small median weights, but correct predictions exhibit a slightly higher, more variable distribution than incorrect ones, suggesting that global flow statistics provide supportive information in specific IoT samples. The CNN expert also shows higher weights for correct predictions than for incorrect ones, suggesting that local feature interactions contribute to accurate recognition in a subset of devices. In contrast, the GRU and LSTM experts maintain low weights for both correct and incorrect predictions, indicating that the constructed sequential and long-range temporal representations play a limited role in the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset.

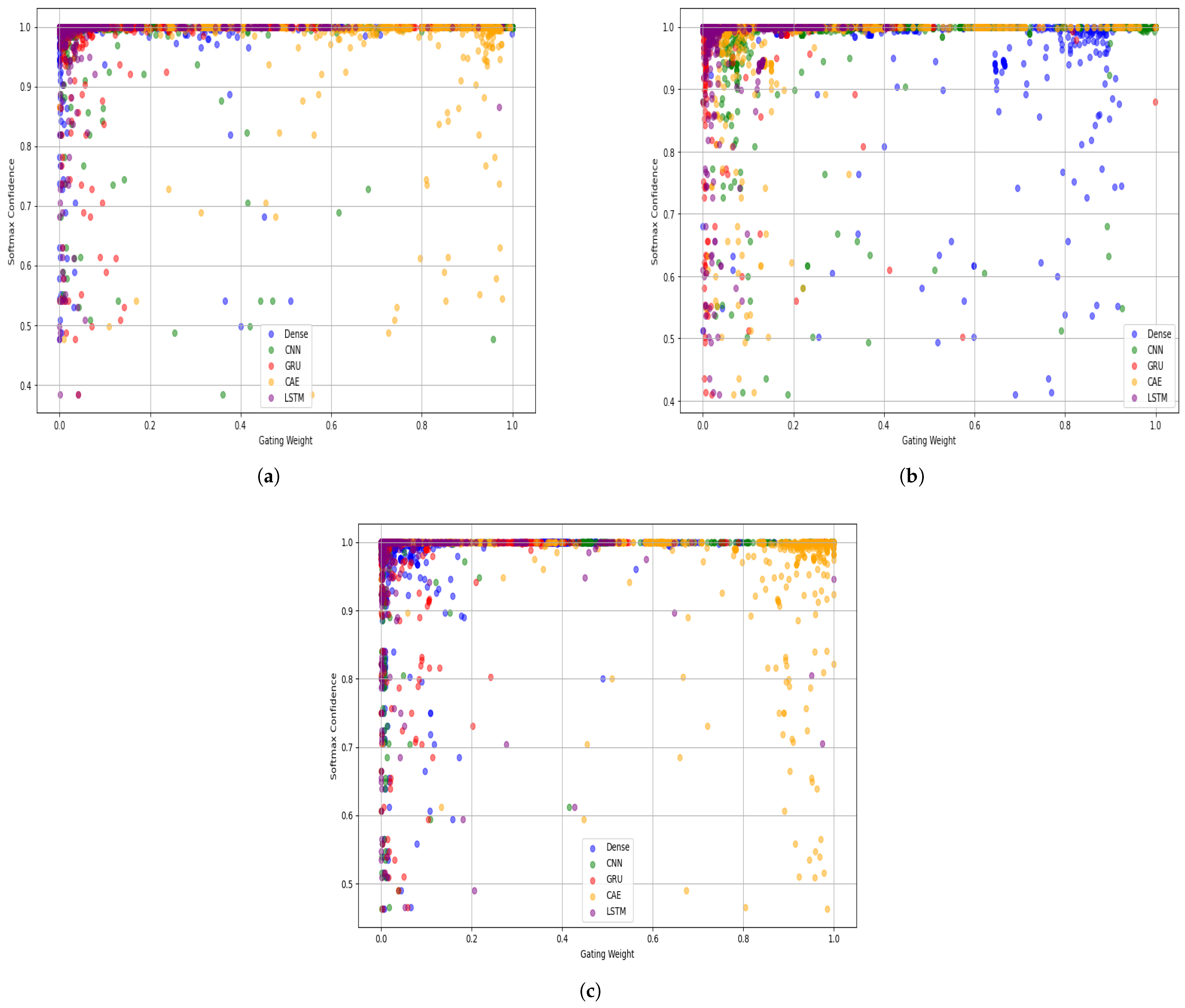

Figure 14 visualizes the relationship between the gating weights and the softmax confidence across all experts for the ISCX VPN-nonVPN, Unicauca, and UNSW-IoTraffic datasets. The majority of highly confident predictions (

) are associated with higher gating weights, especially for specialized experts such as the CAE and CNN modules. This indicates that when the model is more certain about its predictions, it tends to assign more responsibility to the most relevant experts, reflecting an effective expert specialization mechanism. Conversely, samples with lower confidence show more dispersed gating weights, suggesting that the model draws on a broader mix of experts when it is uncertain, highlighting its adaptive nature.

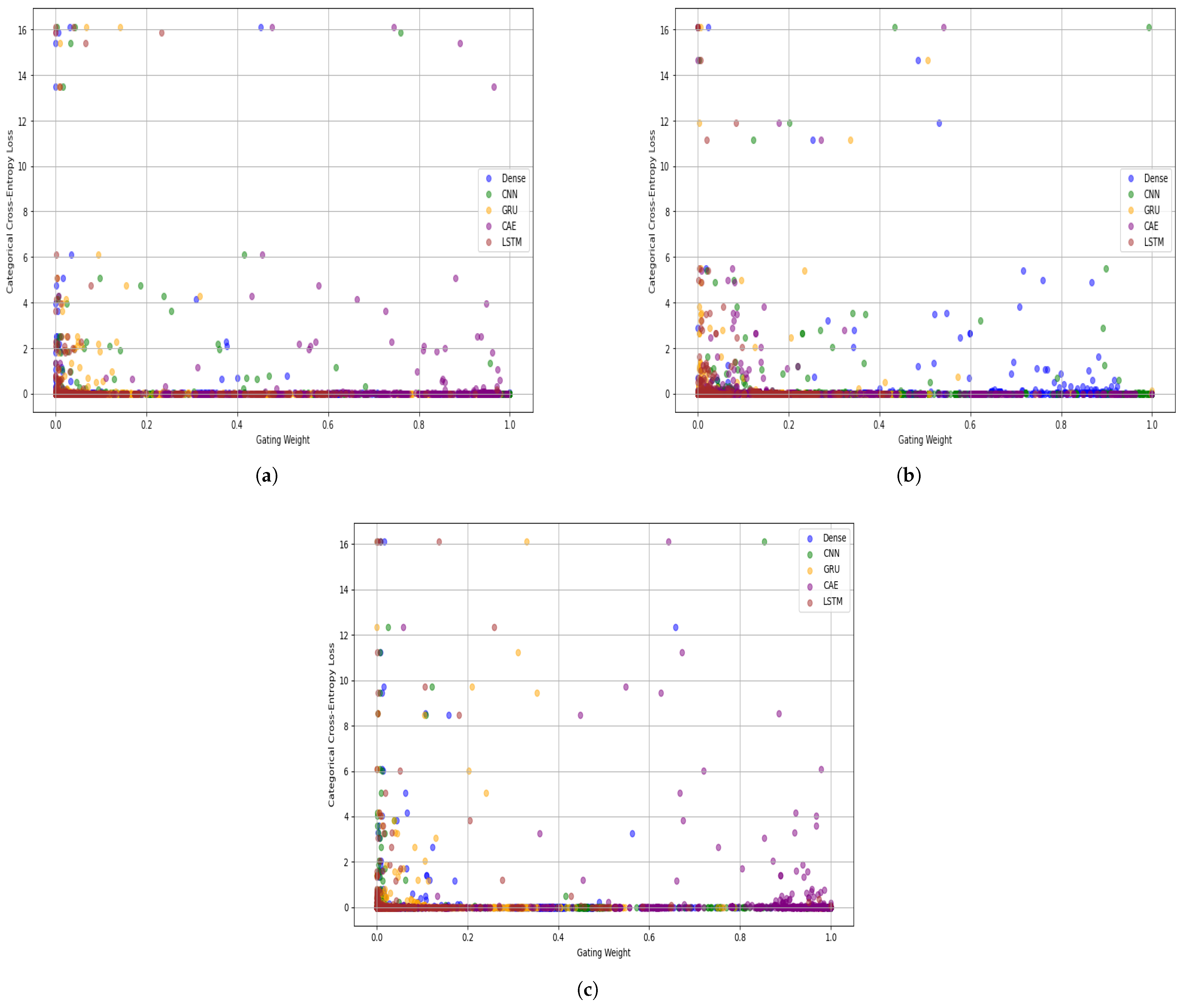

Figure 15 shows the relationship between gating weights and the corresponding categorical cross-entropy loss. Experts with lower gating weights (e.g., GRU and LSTM) often align with higher loss values, indicating that their contributions are less optimal for many samples. Meanwhile, dominant experts such as CAE (in ISCX and UNSW-IoTraffic) and CNN (in Unicauca) not only receive higher weights but also correspond to lower loss regions, underscoring their discriminative strength.

The performance of the proposed ALF-MoE traffic classification framework is compared with other state-of-the-art approaches, as summarized in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8. On the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, the proposed model attained an accuracy of 98.43%, outperforming the competitive techniques reported in [

32,

33,

34,

37,

38]. These results validate the robustness and effectiveness of the ALF-MoE architecture in handling diverse traffic patterns, including encrypted and non-encrypted flows. Similarly, on the Unicauca dataset, ALF-MoE was benchmarked against several state-of-the-art models [

27,

28,

29,

30], and demonstrated superior performance, achieving an impressive accuracy of 98.96%. Moreover, on the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset, we benchmarked ALF-MoE against several baseline models [

47,

54]. ALF-MoE achieved the best performance, reaching an accuracy of 97.93%.

4.7. Complexity Analysis

The training parameters and computational complexity of the proposed ALF-MoE model are summarized in

Table 9. The results show that ALF-MoE remains lightweight, requiring only 90,413 trainable parameters with a compact model size of 1.230 MB. Across all datasets, the inference latency stays in the range of 1.49–2.21 ms per sample, enabling real-time traffic classification with high throughput (452–670 samples/s). The testing time is also small, confirming that the model can process flow samples efficiently during deployment.

4.8. Model Stability Analysis

Table 10 shows the ten-fold cross-validation stability analysis of ALF-MoE for ISCX VPN-nonVPN, Unicauca, and UNSW-IoTraffic. Across all folds, ALF-MoE consistently achieves a high accuracy and macro-F1. A slight fold-to-fold variance shows low sensitivity to the train–test partition. The performance patterns across datasets remain consistent, and no single fold dominates the overall results, indicating that the reported gains are not due to a favorable split.

4.9. Ablation Study

The ablation study assesses the impact of individual components in the proposed ALF-MoE model by selectively disabling key modules and testing single expert variants. On the ISCX VPN-nonVPN dataset, the complete ALF-MoE model achieves the highest accuracy of 98.43%. In contrast, removing the gating network reduces the accuracy to 95.82%, underscoring the critical role of the gating network in adaptive expert selection. Similarly, replacing the ensemble approach with individual expert models such as CNN, GRU, CAE, and LSTM results in decreased performance, with accuracies ranging from 94.02% to 97.85%. The Dense network alone achieves an accuracy of 95.25%, indicating that no single expert can match the capabilities of the ensemble. Comparable trends are observed in the Unicauca dataset, where the complete model reaches an accuracy of 98.96%, while models without the gating module or those that utilize only a single expert achieve lower accuracies, ranging from 95.13% to 98.06%. On the UNSW-IoTraffic dataset, the complete ALF-MoE model achieves the best accuracy of 97.93%, confirming that the complete multi-expert fusion strategy is the most effective for traffic classification. When the gating network is removed, the accuracy drops to 96.91%, highlighting that adaptive expert weighting still provides a measurable benefit even in this device-centric setting. The single expert variants show larger performance degradation, with accuracies ranging from 91.11% (LSTM only) to 96.82% (CAE only), indicating that relying on one feature domain is insufficient to capture diverse IoT traffic behaviors. These results confirm the effectiveness of the multi-expert ensemble architecture and the gating network in enhancing classification performance. A detailed summary of the results can be found in

Table 11.

5. Discussion

The proposed ALF-MoE model achieves strong and consistent traffic classification performance across the ISCX VPN-nonVPN, Unicauca, and UNSW-IoTraffic datasets, with accuracies of 98.43%, 98.96%, and 97.93%, respectively. This demonstrates that the framework generalizes across heterogeneous traffic scenarios, including encrypted and unencrypted flows. Beyond accuracy, the learned expert specializations provide an interpretable view of which feature domains are most informative for a given dataset and class. In particular, the modular design enables the model to capture complementary traffic characteristics, while the gating mechanism adaptively emphasizes the most relevant experts per sample. The additional ALF fusion stage further refines the weighted expert outputs via a non-linear transformation, thereby improving decision boundaries and stabilizing ensemble learning.

Compared with conventional single-backbone deep classifiers and standard ensemble learning, ALF-MoE explicitly decomposes feature learning into domain-specific experts. It then learns data-dependent expert weights through a gating network. This formulation aligns with the broader Mixture of Experts paradigm. However, it differs in two key aspects: (i) the experts are intentionally designed to capture distinct traffic feature modalities rather than being homogeneous subnetworks, and (ii) the final decision aggregation is not a simple weighted sum of logits, but is refined via a learnable fusion module with a non-linear mapping. Empirically, the ablation results confirm that both the gating and fusion strategies contribute to the final performance. This indicates that the gains are not solely due to model capacity but to selective specialization and adaptive combination.

The proposed model is lightweight and suitable for deployment on IoT edge and gateway platforms. The complexity analysis reports the total parameters, model size, latency, throughput, and estimated energy per inference. ALF-MoE is compact in memory (90,413 parameters; 1.230 MB), but multi-expert inference incurs additional computational cost compared with a single backbone. The measured inference latency is 1.49–2.21 ms per sample, and the throughput is 452–670 samples/s. These results indicate that ALF-MoE can support real-time flow-level classification under typical gateway workloads. The most practical deployment point is an IoT gateway or edge node (a home or industrial gateway, a hospital edge server, or a vehicular edge unit), where traffic is aggregated, and resources are less constrained. Direct deployment on ultra-low-power IoT devices would still be complex without further optimization.

Although ALF-MoE achieves strong accuracy, it has several practical limitations. The multi-expert design introduces extra computation compared with a single backbone, even though the overall model size is compact. As a result, the most realistic deployment is on an IoT gateway or edge server rather than ultra-low-power end devices, unless further optimization is applied. Despite near-perfect accuracy for many classes, the model shows performance degradation in overlapping traffic categories. These errors are likely caused by behavioral similarity and protocol overlap across classes. Common ports, payload size patterns, and encryption behaviors can make classes hard to separate. This can lead to confusion even among expert models. Robustness under real-world noise and adversarial traffic shaping is another constraint. We did not fully evaluate scenarios such as packet loss, jitter, or evasion attacks. Cross-dataset generalization and long-term concept drift are also important constraints.

Future work will improve the deployability, robustness, and generalization of ALF-MoE in resource-constrained environments. A key direction is reducing multi-expert overhead by using sparse or top-k expert activation. Additional efficiency gains can be achieved through pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation to support gateway and edge deployments. Another research path is cross-dataset training and testing to assess generalization under different traffic sources. Long-term evaluation is also needed to study distribution shift and concept drift in streaming IoT traffic. To mitigate overlapping classes, class-balanced or focal loss functions can be explored. Metric-learning objectives and feature augmentation offer further opportunities to improve separation for minority and challenging classes.