1. Introduction

A problem is hard if there is no polynomial-time probabilistic algorithm that can solve it with non-negligible probability. There is no known proof that a particular problem is hard. Unsuccessful attempts to solve specific problems efficiently, together with the lack of a proof of hardness, have led to the adoption of so-called

computational hardness assumptions. Such an assumption states that a particular problem is hard. Notice, however, that a hardness assumption is not a mathematical argument, and so, some believed-to-be-hard problems might become easy in the future. Among the problems currently considered hard are the factorization problem for positive integers, the discrete logarithm problem, the decisional and computational Diffie–Hellman problems, and problems specific to residuosity or lattice theory [

1].

Modern cryptographic security relies on computational hardness assumptions via reductions. We will elaborate a bit on this aspect. The security of a cryptographic scheme is studied within a security model that specifies the security goal that needs to be achieved and the attack model against which it is evaluated. Then, is -secure if the problem of breaking ’s security goal through the attack model specified by is hard. This is where the hardness assumptions and the reduction technique come into play. More precisely, to prove that is -secure, we do as follows:

Choose a problem H for which there is a hardness assumption;

Reduce H to in the sense that if breaking the -security of is easy, then H is easy.

The conclusion then is that achieves -security provided that H is hard.

can remain -secure even if the hardness assumption on H is later proven false. However, in such a case, another problem must be found on which to argue for the -security of the scheme . If, however, H and are equivalent in the sense that there is a bidirectional reduction between them, then is -secure if and only if H is hard. In other words, ’s security is fundamentally tied to the hardness of H.

Establishing an equivalence (bidirectional reduction) between the security of a cryptographic scheme and a well-defined hard mathematical problem is critically important for several reasons:

An equivalence means that breaking the cryptographic scheme is equivalent to solving the underlying hard problem. This provides strong theoretical assurance: if the hard problem is truly difficult, then the scheme is secure. So, it shifts the burden of security analysis from ad hoc approaches to a well-understood computational problem;

Computational problems are usually formulated more simply, eliminating details that are not of algorithmic importance (which may appear in the description of a cryptographic scheme);

Specific parameters of the cryptographic scheme, such as the key size, can be chosen based on the best-known algorithms for solving the hard problem underlying the scheme’s security;

It allows easy correlation with other computational problems and so may facilitate security comparisons between cryptographic schemes;

It provides a clearer picture of the security level of the cryptographic scheme.

We will briefly discuss a few examples below (the mathematical notations are standard but the reader can find them in the next section). The (textbook) RSA cryptosystem [

1] is a public-key encryption system. To set up such a system, an integer

is chosen, where

p and

q are distinct odd prime integers. The public key (used for encryption) is of the form

, where

e is coprime with

, and the secret key (used for decryption) is of the form

, where

d is the inverse of

e modulo

. The ciphertext associated with a message

is

, while its decryption is

.

The OWE-CPA security [

1] of the RSA cryptosystem is the following problem: given

and

, determine an integer

such that

. It is clear that if the factorization of

n is easy, then the calculation of the function

is easy, which leads to the easy determination of

d (the inverse of

e modulo

). So, the OWE-CPA security of RSA reduces to factorization or, in other words, the OWE-CPA security of RSA is no harder than factoring. This leaves open the possibility that the OWE-CPA security of RSA is easier than factorization. However, it is an open problem to prove that breaking the OWE-CPA security of RSA efficiently can also factorize the modulus.

In the Rabin cryptosystem [

1], which can be viewed as a special case of RSA, the public key is

n, while the private key consists of the prime integers

. Encryption is performed by squaring the plaintext message

x modulo

n, resulting in the ciphertext

. The decryption of

c needs the Chinese Remainder Theorem with the prime integers

p and

q, leading to four roots of

c modulo

n. Additional information is then needed to identify the original message. Unlike RSA, the OWE-CPA security of the Rabin cipher is equivalent to factoring [

1].

The list of examples can continue with the ElGamal cryptosystem, whose IND-CPA security is equivalent to the decisional Diffie–Hellman problem, or with the Paillier cryptosystem whose IND-CPA security is equivalent to the composite residuosity problem [

1].

Problem formulation: The

quadratic residuosity problem (QRP) is one of the seemingly hard problems. This problem requires that, given the product

n of two distinct prime integers

p and

q and an integer

with Jacobi symbol +1, one must decide whether or not

a is a quadratic residue modulo

n. Since all attempts to solve it efficiently failed, the assumption was adopted that no probabilistic algorithm of polynomial time complexity can distinguish with a non-negligible probability between quadratic residues and quadratic non-residues with the Jacobi symbol +1. This assumption, known as the

quadratic residuosity assumption (QRA), together with the problem of quadratic residuosity, is of great importance in cryptography [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Cocks’s public-key encryption (CPKE) and identity-based encryption (CIBE) schemes [

6] are two well-known cryptosystems that achieve security by indistinguishability under chosen-ciphertext attack (

security), provided that

is hard. That is,

reduces to the

security of any of the two schemes (in the sense we have already discussed: if breaking the

security of any of the two schemes is easy, then

is easy).

The question now is whether the security of the two Cocks cryptosystems reduces to . In other words, the question is whether the security of any of these schemes is equivalent to .

Contribution: We introduce a new computational problem in this paper, called the Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic congruences (), and we show that

- 1.

reduces to . Therefore, is at least as hard as .

- 2.

The security of any of the two Cocks cryptosystems is equivalent to .

As a result, the security of the two Cocks cryptosystems is equivalent to if and only if and are equivalent. We conjecture that is strictly harder than . Regardless of the truth value of this conjecture, we have identified a computational problem, namely , that is equivalent to the security of the two cryptographic schemes mentioned above.

We then specialize to roots of quadratic residues modulo anti-Blum integers. We divide the quadratic residues into two classes according to the Jacobi symbol of their roots, which in turn induces a partition into two classes of the integers with the Jacobi symbol but which are not quadratic residues. Then, we establish computational indistinguishability relationships between these distributions. Thus, we refine the problem of distinguishing between quadratic residues and non-residues depending on the Jacobi symbol of the roots.

Our paper is structured into six sections, the first one being an introduction. The second section establishes the basic notation and terminology for the entire paper. Then, in

Section 3, we present some results on quadratic congruences. The fourth section is dedicated to the computational problem we propose, namely the Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic congruences. Connections between this problem, the quadratic residuosity problem, and the security of Cocks’ schemes are established. The fifth section specializes the Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic congruences to roots of quadratic congruences and establishes several computational indistinguishability results. The conclusions of our work are presented in the sixth section.

2. Preliminaries

We recall here the basic notation and terminology used in the paper. For details the reader is referred to [

1,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

We use to denote the set of integers and for the gcd of the integers a and b (it will be clear from context when is the pair of the two integers and not their gcd). When , the integers a and b are called co-prime. stands for and , for any positive integer n.

Two integers a and b are congruent modulo an integer n, denoted , if n divides . When , the remainder of the integer division of a by n is expressed or .

An RSA integer, also called RSA modulus, is a product of two distinct odd prime integers p and q (as a matter of convention, we always assume ).

Given a system of congruences in the indeterminate

x,

the

Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT) [

14,

15] states that the system has a unique solution modulo

, whenever

are pairwise co-prime.

Given two integers a and , we say that a is a quadratic residue modulo n if , for some integer x; the integer x is called a square root of a modulo n.

Let

p be an odd prime integer. The

Legendre symbol of an integer

a modulo

p, denoted

, is 1 when

a is a quadratic residue modulo

p, 0 when

p divides

a, and

otherwise. The extension to odd moduli

is called the

Jacobi symbol, denoted in the same way as the Legendre symbol is. Thus, the Jacobi symbol of

a modulo

is 1 when

and

if

is the prime factorization of

n (

are distinct prime integers and

, for all

). For ease of expression, we will use the term “Jacobi symbol” for both prime and composite moduli.

Let

(

,

,

) be the set of quadratic residues (quadratic non-residues, integers with the Jacobi symbol +1, integers with the Jacobi symbol

, respectively) from

. The following facts are well-known [

13,

14,

17]:

- 1.

when n is an odd prime integer;

- 2.

For any odd integer , is a quadratic residue modulo n if and only if there is a quadratic residue modulo any prime factor of n;

- 3.

For any RSA modulus , and ;

- 4.

For any RSA modulus

, if we split

into two subsets

and

,

,

, and

partition

into four subsets of equal size. These subsets are called the

quadrants of

.

Probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) algorithms [

16] play an important role in cryptography. For such an algorithm

,

means that

b is an output of

on some input from

D, and

stands for the probability with which

outputs

b. An oracle for

can be viewed as a black box

f that can perform a particular computation whenever it is queried by

. We do not care about

f’s implementation or how it works. We only assume that

f returns the computation result in

time complexity. The notation

is used to specify that

may query the oracle

f.

A positive function is negligible if for any polynomial function there is such that , for any . If is negligible, then is called overwhelming.

When a problem cannot be solved by any PPT algorithm, except with negligible probability, we will say that it is hard; otherwise, it will be called easy. The problem Areduces to the problem B, denoted , if A’s hardness implies B’s hardness (equivalent to saying that A is easy assuming B is easy). If and , then A and B are called equivalent, denoted .

A (discrete) probability distribution over a discrete sample space D is a real-valued function X with the properties for any and . We will omit the sample space D whenever it is clear from the context. When a probabilistic algorithm receives inputs from a sample space over which we have defined a probability distribution X, we will say that the algorithm gets inputs from X and write .

A

distinguisher for a probability distribution

X is a PPT algorithm

whose output lies in

for any input in

X. The

advantage of a distinguisher

on two families of probability distributions

and

over the same sample space, denoted

, is defined as being the function

X and Y are called computationally indistinguishable, denoted , if is negligible, for any distinguisher .

Let and be two finite sets of messages and ciphertexts, respectively. A public-key encryption (PKE) scheme over is a triple of algorithms , where

: is a PPT algorithm that takes as input a security parameter and outputs a pair consisting of a public key and a secret key ;

: is a PPT algorithm that takes as input a public key and a message m and outputs a ciphertext;

: is a deterministic polynomial-time (DPT) algorithm that takes as input a private key and a ciphertext c and outputs a message m or a special symbol ⊥ denoting failure. It is required that , for all outputs of , all messages m, and all outputs c of .

To define the

security of a PKE scheme

, consider the probabilistic Algorithm 1, where

is a PPT algorithm and

. Thus, we say that

has

indistinguishable encryptions under chosen plaintext attack or that it is

secure if the advantage

of

against

is negligible for any PPT

, where

We will denote by

the problem of breaking the

security of the PKE scheme

.

| Algorithm 1: security game |

- 1.

; - 2.

with and ; - 3.

; - 4.

; - 5.

Return .

( denotes state information). |

Identity-based encryption (IBE) is a form of PKE, where the public key can be computed by the sender, while the corresponding private key has to be computed by a dedicated key generator. So, an IBE scheme over consists of four PPT algorithms as follows:

- 1.

: is a PPT algorithm that takes as input a security parameter and outputs the system public parameters together with a master key ;

- 2.

: is a PPT algorithm that takes as input the master key and an identity , and outputs a private key associated with ;

- 3.

: is a PPT algorithm that, starting with the public parameter , an identity , and a message m, encrypts m into some ciphertext c (the encryption key is some binary string derived from );

- 4.

: is a DPT algorithm that takes as input a secret key associated with some identity and a ciphertext c, and outputs a message m or a special symbol ⊥ denoting failure. It is required that , for all outputs of , all identities , all messages m, all outputs c of , and all outputs of .

The concept of

security can be extended to IBE schemes as well by means of Algorithm 2. We say that

has

indistinguishable encryptions under chosen plaintext attack or that it is

-secure if the advantage

of

against

is negligible for any PPT

, where

We will denote by

the problem of breaking the

security of the IBE scheme

.

| Algorithm 2: security game |

- 1.

; - 2.

with and ; - 3.

; - 4.

; - 5.

Return .

( denotes state information. It is assumed that the identity in step 3 was never queried for private key extraction in steps 2 and 4). |

3. Quadratic Congruences

We present in this section some results on solving quadratic congruences modulo a prime integer and an RSA modulus. For the completeness of the presentation, a few known results are recalled in an appropriate form and accompanied by brief proof sketches.

3.1. Quadratic Congruences Modulo a Prime Integer

We will focus on solving quadratic congruences

where

p is an odd prime integer and

. For the congruence not to degenerate into a linear one, we will ask for

. Under this requirement, we may multiply the quadratic congruence by

without changing its solutions. So, we may consider the quadratic congruence in the equivalent form

. For technical reasons, we write the congruence in the form

where

. If

, the congruence becomes

, which trivially leads to the solutions 0 and

c in

. As a result, we will avoid this case and, in what follows, we assume

.

Although not presented in this form, the following result is part of any standard textbook on number theory, such as [

13,

14].

Proposition 1 (Solving quadratic congruences). Let p be an odd prime integer, , , and .

- 1.

If , then

- (a)

The congruence (2) has two distinct solutions in , namely and , where is an arbitrary root modulo p of Δ; - (b)

If is one of the solutions for (2), then is the other solution in ; - (c)

The two solutions in for (2), t and , satisfyTherefore, they have the same Jacobi symbol modulo p if and only if ;

- 2.

If , then

- (a)

, and so and ;

- (b)

The congruence (2) has a (double) solution in , namely , which is also one of the two roots in of a;

- 3.

If none of the above occurs, the congruence (2) has no solution.

Proof. According to the hypothesis, the congruence (

2) is equivalent to

which in turn can be re-written as

It is now clear that the congruence (

2) has solutions only if

or

. This answers the last item of Proposition 1.

1. Let us assume that

is a quadratic residue modulo

p. Then, (

4) leads to

from which follows that

and

are solutions in

for (

2). It is straightforward to check that they are non-congruent modulo

p. If we assume that

p divides one of them, then

p divides their product and so,

, which is a contradiction. Therefore, both solutions are in

, and thus 1(a) is proved.

Here, 1(b) requires only a simple check, and 1(c) follows from the basic properties of the Jacobi symbol.

2. If , then , and so (remark that by the hypothesis). Moreover, . Therefore, 2(a) is proved.

To prove 2(b), remark that (

4) becomes

, which leads to the (double) solution

in

. □

Each solvable congruence is precisely defined by

- 1.

The odd prime integer p;

- 2.

, which is the product modulo p of the solutions in ;

- 3.

, which is the sum modulo p of the solutions in .

Given

p and

a as above, we can count the solvable quadratic congruences (

2) by counting the integers

for which the discriminant

is zero or in

. This, however, reduces to counting the pairs of solutions

because

(remark that

if and only if

and

t is a square root of

a modulo

p).

Given an odd prime integer

p,

, and

, define the set

We note that the sets

make sense only in the case

. If

, then the solutions of the congruence (

2), when solvable, have different Jacobi symbols.

Proposition 2. Let p be an odd prime integer and . Then, Proof. Let p and a be as in the statement of the proposition. The following facts are straightforward:

a has two distinct roots in .

If is not a root of a, then . If is a root of a, then .

For any , t and have the same Jacobi symbol.

If and , then and are disjoint sets.

Now, we consider the following two cases.

Case 1: . In this case, is even, and both roots of a are either in or in .

Each

that is not a root of

a defines, together with

, a unique congruence of type (

2) whose roots are distinct and have the same Jacobi symbol. Each root

of

a defines a unique congruence of type (

2) whose roots are equal to

r and have the same Jacobi symbol. Since both roots of

a are either in

or in

, one of the sets

and

will have

elements while the other will have

elements.

Case 2: . In this case, is odd, and the roots of a are one in and the other in .

The reasoning follows as in Case 1, but with the difference that the roots of a exist as one in and one in , so the sets and will have the same number of elements, which is . □

A brief discussion on the complexity of computing the solutions of a quadratic congruence modulo a prime integer concludes the section.

Remark 1. The calculation of solutions for the congruence (2) requires first to decide whether the discriminant Δ is a quadratic residue modulo p. This can be decided in polynomial time by computing the Jacobi symbol of Δ modulo p [15]. If , its roots can be computed in polynomial time , where for some odd integer m [15]. This gives also the final complexity to compute the solutions. 3.2. Quadratic Congruences Modulo a Composite Integer

Solving quadratic congruences in which the modulus is a composite integer calls on the CRT and Hensel’s lifting lemma [

13,

14]. However, in what follows, we will only consider quadratic congruences (

5) with an RSA modulus

and a free coefficient

a co-prime with

n.

Therefore, to solve these congruences, we will only need CRT. According to it, solving the congruence (

5) reduces to combining the solutions of the congruences (

6) and (

7) using CRT.

As a result, if (

6) and (

7) are solvable, they may have each one or two solutions in

and

, respectively, which implies that (

5) may have one, two, or four solutions in

. Thus, if

is a solution for (

6) and

is a solution for (

7), then the unique solution modulo

of the system

is a solution for (

5). In addition, distinct pairs

as above give rise to distinct solutions modulo

for (

5), and all solutions modulo

for (

5) are obtained in this way [

13,

14].

The system (

8) has exactly one solution modulo

, whose form is shown below.

Lemma 1. Let p and q be two distinct odd prime integers, , and . Then, the unique solution modulo for the system (8) has the formwhere and . Moreover, Proof. The first part of this lemma simply follows from the CRT [

13,

14]. For the second part, remark that

and

Then, apply basic computation rules for the Jacobi symbol. □

To decide if a quadratic congruence has one, two, or four solutions, modulus factorization is not necessary.

Lemma 2. Let be an RSA modulus. If the congruence (5) is solvable, we can efficiently decide whether it has one, two, or four solutions in without knowing the factorization of n. Proof. Let . One can easily check that

The congruence (

5) has exactly one solution in

when

;

The congruence (

5) has exactly two solutions in

when

but

;

The congruence (

5) has exactly four solutions in

when the first two cases are not met (remark that our hypothesis stipulates that the congruence is solvable).

The proof ends by observing that we can efficiently compute the Jacobi symbol without knowing the factorization of n. □

The following two propositions make beneficial connections between

a’s residuosity and the Jacobi symbol of the solutions for (

5).

Proposition 3. Let be an RSA modulus. Assume that the quadratic congruence (5) is solvable and . Then, if and only if all solutions in for (5) have the same Jacobi symbol. Proof. Assume (

5) is solvable. Then, both (

6) and (

7) are solvable (each of them having one or two solutions in

and

, respectively). So, (

5) may have one, two, or four solutions in

.

According to Lemma 2, the solutions for (

5) have the same Jacobi symbol if and only if each of the congruences (

6) and (

7) has solutions with the same Jacobi symbol (independently of each other). But this is equivalent to the fact that

and

, which in turn is equivalent to

. □

Proposition 4. Let be an RSA modulus. Assume that the quadratic congruence (5) is solvable and . Then, - 1.

if and only if the congruence (5) has two or four non-congruent solutions in , half of them having the Jacobi symbol and the other half, . - 2.

if and only if the congruence (5) has four non-congruent solutions in , distributed one by one in the four quadrants of .

Proof. Assume (

5) is solvable. Then, both (

6) and (

7) are solvable.

1. Assume that

. Then,

or

. Therefore, at least one of the two congruences (

6) and (

7) have two non-congruent solutions (in

or

) of opposite Jacobi symbols (Proposition 1(1c)). The other congruence may have two solutions of opposite or the same Jacobi symbols, or it may have one solution (Proposition 1(2)). So, (

5) has two or four solutions in

, having the distribution of Jacobi symbols as specified in the proposition.

Conversely, the hypothesis shows that at least one of the two congruences (

6) and (

7) has two non-congruent solutions of opposite Jacobi symbols. Suppose that this is the congruence (

6). Then

(Proposition 1(1c)). As with respect to

, this may be in

or

. As a result,

.

Here, 2 is a special case of 1. The congruence (

5) has four solutions in

if and only if each of the congruences (

6) and (

7) has two solutions in

and

, respectively. In addition, the four solutions are distributed one by one in the four quadrants of

if and only if each of the congruences (

6) and (

7) has solutions with different Jacobi symbols (independently of each other). But this last fact is equivalent to

and

, which in turn is equivalent to

. □

Let

be an RSA modulus,

, and

. Extending the notation from the previous section to RSA moduli, denote by

the set

Proposition 5. Let be an RSA modulus and . Then, Proof. Each pair of integers

produces a unique integer

, and each integer

comes from a single pair of integers

as above (Lemma 1).

Likewise, each pair of integers

produces a unique integer

, and each integer

comes from a single pair of integers

as above.

From Proposition 2, by a simple computation, we arrive at the proposition’s conclusion. For illustration, let us consider just one case. Let

,

,

, and

. Then,

and

Therefore, . □

A brief discussion on computing the solutions for a quadratic congruence modulo an RSA integer concludes the section.

Remark 2. The calculation of solutions for the congruence (5) requires the factorization of . If it can be done in polynomial time, then the solutions can be computed in polynomial time (we compute the solutions for (6) and (7) and then combine them with the CRT). However, factorization of large RSA moduli is a hard problem and no other method that avoids it is known to compute solutions for (5). 4. The Jacobi Symbol Problem for Quadratic Congruences

The Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic congruences, abbreviated , is the problem to compute the Jacobi symbol of the solutions to a solvable quadratic congruence whose free coefficient is a quadratic residue with respect to an RSA modulus. appears to be a hard problem in the sense that no PPT algorithm can solve it with non-negligible probability.

We formalize below as a distinguishing problem between two probability distributions. Let be an RSA moduli generator, that is, on some input , it outputs , where p and q are two odd distinct primes of the same size and . In what follows, we will simply write instead of , whenever it is not necessary to emphasize the factorization of n.

We define now four families of probability distributions

and

, where

, as follows:

We may say that

is the probability distribution of solvable quadratic congruences (

5) whose solutions have the same Jacobi symbol

s (see also Proposition 3). So,

is the problem to distinguish between

and

.

The probability distributions and will be technically necessary. According to Proposition 4, they are identical.

4.1. and

We prove here that the quadratic residuosity problem reduces to .

Let

be an RSA moduli generator. This generator gives rise to two probability distributions

and

of quadratic residues and non-residues, as follows:

The

quadratic residuosity problem is the problem to distinguish between

and

[

18]. This is considered a hard problem. More precisely, the following assumption is adopted.

Definition 1. We say that the quadratic residuosity assumption () holds for a generator if the distributions and , defined by means of , are computationally indistinguishable.

The following result shows that is harder than .

Theorem 1. .

Proof. Assume that

holds for a generator

. Then, the following relationships hold:

So,

and

are computationally indistinguishable. □

Whether is strictly harder than remains an open question. However, we conjecture that this question has a positive answer.

4.2. and Cocks’ PKE Scheme

In the following, we will connect

and the

security of Cocks’ PKE (CPKE) scheme [

6]. The CPKE scheme encrypts bits in

. It uses quadratic residues as public keys, while their roots are the secret keys. Its correctness follows easily from the congruence

(please see the scheme for the meaning of the parameters).

![Mathematics 14 00465 i001 Mathematics 14 00465 i001]() |

| Cryptographic scheme 1: Cocks’ PKE scheme |

A straightforward analysis of the scheme shows that its security is equivalent to the indistinguishability of the distributions and .

Theorem 2. .

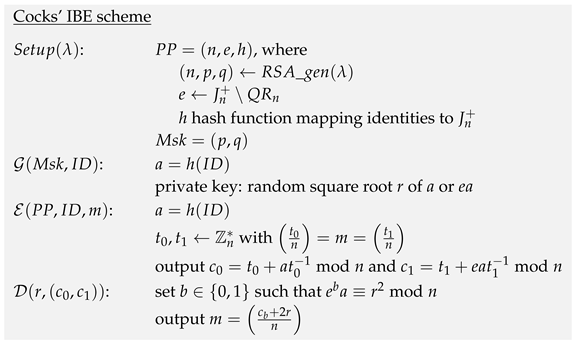

4.3. and Cocks’ IBE Scheme

Cocks’ IBE (CIBE) scheme [

6] has a setup phase where an RSA modulus

n, a random integer

, and a hash function

h are published. The function

h returns elements in

, whenever it is applied to identities. As

is either a quadratic residue or an element in

, exactly one of

a and

is a quadratic residue. So, the CIBE scheme encrypts as CPKE does, but with both “public keys”,

a and

.

![Mathematics 14 00465 i002 Mathematics 14 00465 i002]() |

| Cryptographic scheme 2: Cocks’ IBE scheme |

A simple analysis of the CIBE scheme shows that its

security is equivalent to the indistinguishability of the distributions

and

given by

where

, by adversaries that are allowed to query the hash function and the private key generator.

Now, we are ready to prove the following theorem.

Theorem 3. . Under the assumption that the hash function in is implemented as a random oracle, the converse reduction also holds.

Proof. First, assume that is easy and prove that is easy. As , the hypothesis shows that QRP is easy. So, there exists an adversary that has a non-negligible advantage against and an adversary that has a non-negligible advantage against .

Define a distinguisher that on an instance , where for some , does as follows:

- 1.

Run to decide with non-negligible probability whether a or is a quadratic residue;

- 2.

Run on if the answer of is 1 (that is, a is a quadratic residue), and on , otherwise;

- 3.

outputs what outputs.

Remark that does not need to query any oracle for h or private key generation. Clearly, has a non-negligible advantage to distinguish from which of the two distributions or the instance comes. So, is easy.

Vice versa, assume that is easy and let be an adversary that has non-negligible advantage against it. Moreover, assume that the hash function used to compute public keys from identities is a random oracle.

Let be a instance, where for some . Recall that . Define a distinguisher that on does as follows:

- 1.

;

- 2.

;

- 3.

Compute ;

- 4.

Run on , simulating for it a random oracle for hash function h and an oracle for private key calculation as follows:

When queries h on the identity for the first time, randomly generates and a bit , returns to and also stores in its internal database.

For any other query, will return the same value.

When queries a private key for the identity and is in its database for some v and b, will return v, if , and , otherwise.

If the private key query occurs for the first time, first computes as above and then answers the private key query.

It is quite clear that h implemented in this way is a random oracle.

- 5.

returns what returns.

Two cases are to be analyzed.

Case 1: . Then, has the same probability has to guess the Jacobi symbol of the solutions.

Case 2: . Then, has the probability 1/2 to guess the Jacobi symbol of the solutions because each of them is equally probable.

Therefore,

So,

has a non-negligible advantage against

, showing that this problem is easy. □

5. The Jacobi Symbol Problem for Square Roots

We specialize the results from the previous section to square roots of

or, equivalently, solutions to the congruence

But for that, we need a little discussion on the integer −1.

Remark 3. It is well-known that, given an odd prime p, if and only if [14]. Based on this, the following equivalences can easily be established: - 1.

For any odd integer , if and only if , for any prime factor p of n. Therefore, if at least one prime factor of n is congruent to 3 modulo 4, is not a quadratic residue modulo n.

- 2.

For any RSA modulus , if and only if .

RSA moduli with the property are called Blum integers

[19,20]. To have appropriate terminology for the opposite case, we refer to the RSA moduli with , as anti-Blum integers.

Remark 4. Let be an RSA modulus and . Then, from Remark 3 we obtain the following properties:

- 1.

if and only if n is an anti-Blum integer;

- 2.

if and only if n is a Blum integer.

Now, from Propositions 3 and 4 and Remark 4 we obtain the following result.

Corollary 1. Let be an RSA modulus and .

- 1.

All four roots of a modulo n have the same Jacobi symbol if and only if n is an anti-Blum integer.

- 2.

The four roots of a modulo n are distributed one by one in the four quadrants of if and only if n is a Blum integer.

Given

n an anti-Blum integer and

, define the following set of quadratic residues modulo

n:

As

n is an anti-Blum integer, all roots of

have the same Jacobi symbol

s.

Proposition 6. Let n be an anti-Blum integer. Then, the following properties hold:

- 1.

If or , then ;

- 2.

If and , then ;

- 3.

If , then , for any ;

- 4.

and are disjoint, have the same cardinality, and their union is .

Proof. Here, 1 and 2 follow easily from the definition of the sets and .

3. Let and . If is a root of a modulo n, is a root of modulo n. Moreover, . So, .

4. Directly from the definition follows that and are disjoint, and their union is . To prove that they have the same cardinality, remark that and exactly four integers from define a distinguished integer in , for any . □

Given

and

, define the set

by

Proposition 7. Let n be an anti-Blum integer. Then, the following properties hold:

- 1.

The sets and are disjoint and have the same cardinality, and their union is , for any .

- 2.

, for any with and any .

- 3.

, for any with .

Proof. 1. It is trivial to check that the two sets are disjoint and their union is , for any . It is also immediately verified that , for any . As (Proposition 6(4)), it follows that .

2. Let with and . We show that for any there exists such that . This will prove that , and the converse inclusion would follow a similar proof line.

Indeed, if we take

we obtain

. Therefore, we only need to prove that

. But that comes down to showing that

. The congruence

shows that

is a root of

modulo

n, for any root

t of

modulo

n. As

it follows that

.

3. The proof is similar to that in item 2, except that this time we will prove that . □

Example 1. Let and . Then, is an anti-Blum integer. The set has 12 integers, distributed as follows: If we take , we obtain As and , and .

Given

n an anti-Blum integer, the set

is partitioned into four equally sized subsets as shown in

Figure 1. The subsets

and

can change each other depending on

b and the source from where they come (

or

), but not as content (Proposition 7(3)).

We now introduce the Jacobi symbol problem for square roots, abbreviated , as the problem to compute the Jacobi symbol of the square roots of a quadratic residue modulo an anti-Blum integer. The problem can be formalized as a distinguishing problem between two probability distributions.

Let

be an anti-Blum integer generator. Define two families of probability distributions

, where

, as follows:

So,

is the problem to distinguish between

and

.

It is believed that is hard even for Blum integers. There is no argument that would be easy for anti-Blum integers. As a result, we will postulate that this sub-problem of , abbreviated , is also hard. Similar assumptions to (Definition 1) can be formulated for Blum and anti-Blum generators.

The partition

in

Figure 1 allows us to refine the problem of distinguishing between quadratic residues and non-residues depending on the Jacobi symbol of the roots.

Let

be a sequence of integers with the property

, whenever

n is an anti-Blum integer. Define another two families of probability distributions

, where

, as follows:

Then, the following results follow immediately.

Proposition 8. Let be a sequence of integers as above and . Then, the following properties hold:

- 1.

if and only if ;

- 2.

If then .

We believe that the converse of Proposition 8(2) also holds.

6. Conclusions

Establishing a bidirectional reduction (equivalence) between the security of a cryptographic scheme and a computational problem is crucial. Such a reduction shows that breaking the scheme is equivalent to solving the underlying problem. Therefore, either the cryptographic scheme is secure or a major breakthrough has been achieved in solving a well-studied computational problem with deep implications beyond cryptography.

The quadratic residuosity problem () is considered hard and is crucial in cryptography. It is well known that the security of Cocks’ public-key and identity-based cryptosystems is as hard as . However, it is not known whether is equivalent to the security of the two cryptosystems.

In this paper, we have introduced the Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic congruences () and shown that it is at least as hard as . We have also proved that the security of the two cryptosystems mentioned above is equivalent to .

If

and

were equivalent, we would have a positive answer to the open problem mentioned above. We conjectured that

is much harder than

. Regardless of the truth of this conjecture, we highlighted a computational problem equivalent to the

security of the cryptosystems mentioned above. This equivalence entails the benefits discussed in

Section 1 of the paper.

We believe that either answer to the proposed conjecture contributes to the understanding of quadratic residuosity, both from a mathematical point of view and from its cryptographic applications.

Specializing to congruences , where n is an anti-Blum integer and a is a quadratic residue, we obtain the Jacobi symbol problem for quadratic residues (). is then partitioned into two subsets of quadratic residues whose roots have the Jacobi symbol () and quadratic residues whose roots have the Jacobi symbol (). This partition induces a corresponding partition on . can then be nuanced, taking into account the Jacobi symbol of the roots.