1. Introduction

The aim of this study is to develop an optimal control simulation framework capable of generating overtaking trajectories while accounting for aerodynamic wake effects acting on the attacking vehicle. The vehicle model represents a 2024 FIA Formula 3 car and is derived through correlation with real lap telemetry data provided by Campos Racing. Both the vehicle model and the optimal control problem are implemented using Dymos, an open-source optimal control library in Python V3.12 that employs direct collocation and nonlinear programming solvers for trajectory optimisation [

1].

The approach adopted in this work follows a two-step solution strategy. First, an optimal trajectory for a single vehicle is generated around the track by solving a minimum-time optimal control problem. This trajectory is then fixed and used as the reference motion for the leading car. In the second step, an active car solves its own optimal control problem while following the reference vehicle and experiencing aerodynamic wake disturbances generated by the car ahead. The aerodynamic wake model is derived from experimental and numerical studies available in the literature, enabling a realistic representation of aerodynamic losses during close following [

2,

3,

4].

The results of this study are analysed by comparing the racing line of the active car with that of the single-car reference trajectory. Particular attention is given to where and why the active car deviates from the ghost trajectory. These deviations are interpreted in terms of the underlying vehicle physics, including trade-offs between downforce recovery, aerodynamic balance, and geometric curvature of the racing line. From this analysis, key trends are identified regarding strategies that maximise performance while following another car.

This problem is of particular importance because aerodynamic wake is one of the primary barriers to overtaking in modern Formula racing. Recent studies on overtaking fundamentals have highlighted that overtaking performance is highly sensitive to wake strength and that stronger wake effects significantly increase the pace advantage required to complete an overtake [

5]. By investigating how optimal trajectories adapt under wake influence, this study addresses a central challenge in motorsport, namely identifying how performance can be maximised when following another car and where overtaking opportunities are most likely to arise.

Aerodynamic wake effects occur when a following vehicle drives through the turbulent airflow shed by a leading car. These effects typically reduce both downforce and drag and introduce destabilising shifts in aerodynamic balance, with magnitude strongly dependent on the relative longitudinal and lateral separation between vehicles [

2,

4]. Maximum disturbance occurs when the trailing vehicle is directly behind the leader at short longitudinal gaps, while the effects decay as distance increases and as lateral separation grows.

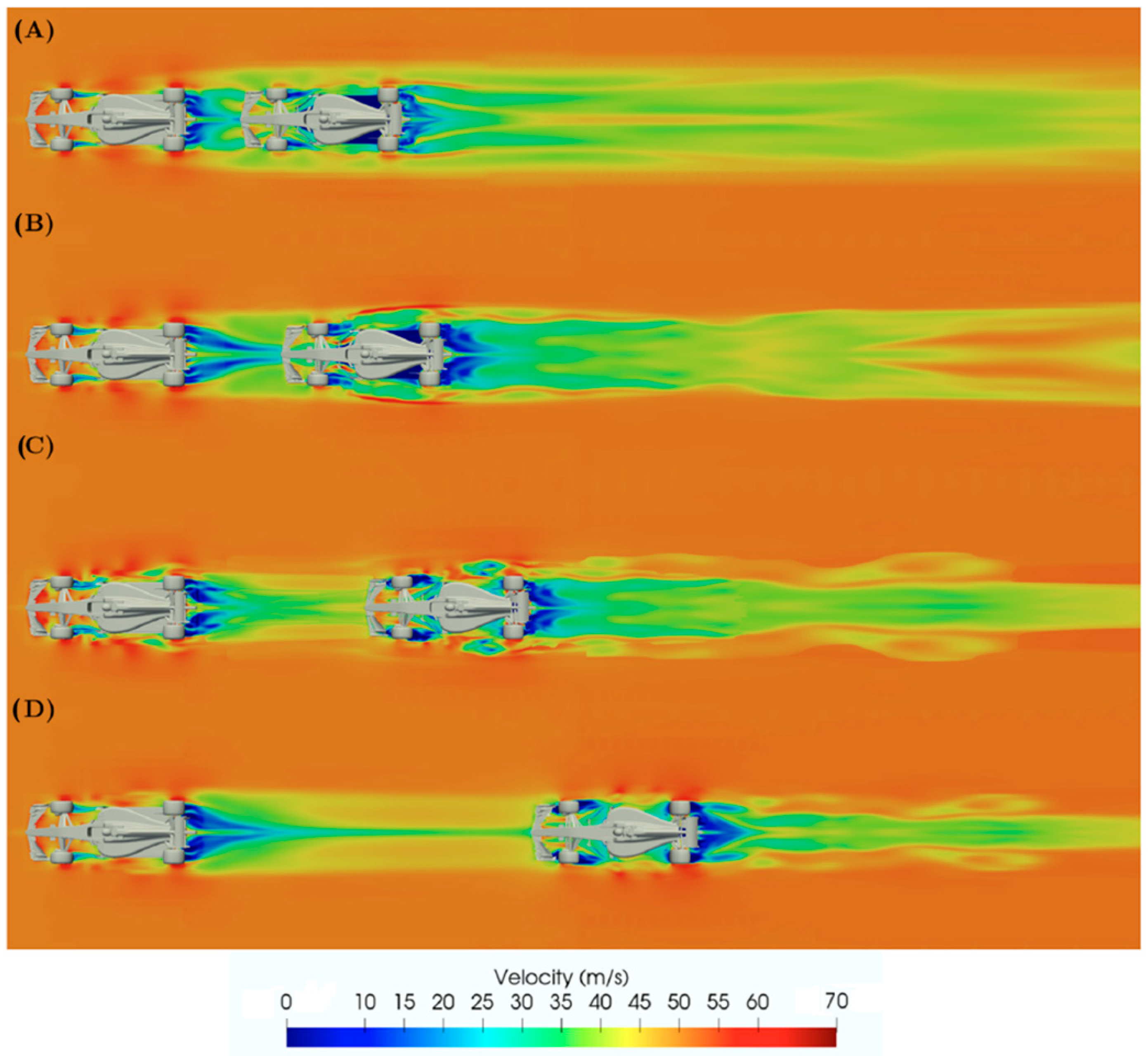

Figure 1 illustrates typical wake flow structures and velocity deficits behind an upstream vehicle at various spacings.

Lap time simulation is a fundamental tool in motorsport, enabling teams and drivers to optimise performance by exploring vehicle dynamics, driving strategies, and circuit characteristics in a virtual environment. Traditional quasi-steady-state (QSS) simulations remain widely used due to their computational efficiency. In these approaches, the lap is decomposed into a sequence of steady-state manoeuvres, effectively representing snapshots of the vehicle at static equilibrium under given operating conditions [

6]. However, QSS simulations rely on a predefined racing line, which makes them unsuitable for analysing overtaking manoeuvres where the optimal path must adapt dynamically to vehicle interactions.

By contrast, transient optimal control methods employ dynamic vehicle models to solve for both the trajectory and control inputs that minimise lap time. These methods treat the problem as a constrained nonlinear optimisation, in which the objective function and system constraints are typically nonlinear. As a result, nonlinear programming techniques are required, since closed-form analytical solutions are generally not feasible except for highly simplified systems. A key insight from this class of methods is that the optimal racing line is not universal but depends strongly on vehicle-specific properties such as downforce level, tyre characteristics, and mass distribution [

7]. This makes optimal control particularly well-suited for investigating overtaking and vehicle performance when following another car, where wake effects are strongly racing-line dependent.

Optimal control has therefore become a widely adopted approach for lap time simulation, as it enables co-optimisation of both trajectory and control inputs while capturing transient vehicle dynamics [

3,

7,

8,

9]. Typical formulations treat the problem as a nonlinear programming problem and solve it using interior-point or sequential quadratic programming algorithms. Applications reported in the literature include optimisation of limited-slip differential behaviour, active aerodynamic devices, and trajectory planning under physical input constraints. Vehicle models employed in these studies are commonly planar, allowing additional subsystem models to be incorporated while maintaining computational tractability.

The direct transcription approach, which discretises the continuous-time optimal control problem using methods such as direct collocation, has proven particularly practical for complex racing applications. Indirect methods offer high accuracy but require strong initial guesses and detailed derivations of necessary conditions, which limit their applicability to large-scale problems. In contrast, direct collocation formulations, such as those implemented in Dymos, allow complex dynamics and constraints to be incorporated more flexibly while maintaining numerical robustness [

9]. For these reasons, direct collocation was adopted in the present study.

In this research, a planar vehicle model is adopted to represent the dynamics of the Formula 3 car. This modelling choice provides a balance between physical fidelity and computational efficiency, which is essential for solving large-scale optimal control problems involving aerodynamic wake interactions and collision avoidance constraints.

Previous studies have shown that planar vehicle models are not inherently limited in their ability to represent complex racing dynamics. For example, planar formulations have been extended to include aerodynamic wake effects [

3], torque vectoring and drivetrain control [

8], nonlinear tyre behaviour including combined slip and load sensitivity [

7,

9], and aerodynamic loads dependent on ride height and wing angle of attack [

10]. These extensions demonstrate that planar models can capture the dominant dynamics relevant to lap time optimisation and overtaking studies while remaining suitable for numerical optimisation.

Recent work has also investigated passing behaviour from a traffic-flow perspective using hydrodynamic and stability-based modelling frameworks. Zhai et al. (2024) [

11] proposed a mixed lattice hydrodynamic model incorporating perceptual-range differences between connected autonomous vehicles and human-driven vehicles to analyse congestion patterns and passing effects on road networks. While such approaches provide valuable insight into macroscopic traffic stability and lane-changing behaviour, they do not address high-performance racing conditions involving aerodynamic wake interaction, tyre force saturation at the limit of handling, or track-constrained minimum-time trajectory optimisation. Consequently, these models are not directly applicable to overtaking analysis in motorsport.

Aerodynamic wake has been identified as one of the primary barriers to overtaking in modern Formula racing. Empirical and simulation-based studies indicate that wake-induced downforce loss significantly reduces cornering performance and increases the pace advantage required for successful passing manoeuvres [

4,

5]. This highlights the importance of modelling frameworks that explicitly capture wake-dependent performance degradation and its influence on optimal driving strategies across braking, cornering, and acceleration phases.

The overtaking and defending problem in motorsport has been studied primarily using Model Predictive Control (MPC) [

12,

13] and optimal control frameworks. An optimal-control-based strategy was presented by [

3]. In that study, the lead vehicle trajectory is generated by solving a Minimum Time Manoeuvre (MTM) problem, yielding the lead vehicle’s position, velocity, and timing profiles along the track. This trajectory is then treated as fixed and used as the upstream vehicle motion. The overtaking vehicle is subsequently formulated as a second MTM problem, in which the lead vehicle trajectory introduces additional constraints, including a hard collision-avoidance zone rather than a penalisation term in the objective function. Liu’s formulation extends the classical MTM approach by incorporating the aerodynamic wake of the lead car, allowing the trailing vehicle trajectory and control inputs to be optimised under disturbed aerodynamic conditions. The problem is transcribed using Legendre–Gauss–Radau collocation and solved as a large-scale nonlinear programming problem using GPOPS-II and IPOPT. A key assumption in Liu’s work is that the leading car does not alter its trajectory and exhibits no defensive behaviour, and the reported results are largely limited to straight-line racing line and overtaking cases. While this demonstrates the feasibility of integrating aerodynamic wake effects within an optimal control framework, it does not capture the additional complexity introduced by cornering phases. The present study extends this analysis to the full racing line, including cornering, where aerodynamic wake not only reduces downforce and drag but can also alter the optimal trajectory itself. This broader treatment enables investigation of wake effects on racing lines and overtaking dynamics under more representative circuit conditions.

Motorsport-specific optimal control studies that include aerodynamic disturbances have demonstrated the importance of slipstream effects on acceleration performance, particularly during straight-line drafting. For example, Liu et al. (2024) [

3] incorporated wake-dependent drag and downforce losses into an optimal control formulation to assess overtaking feasibility under aerodynamic interaction. However, the analysis was primarily focused on straight-line segments, where drag reduction dominates performance gains. The influence of wake effects on full cornering trajectories, including racing line adaptation and traction-limited corner exit behaviour, remains insufficiently explored in existing optimal control formulations.

Building on [

3], the present study applies an optimal control framework to the overtaking problem. Optimal control is adopted because it enables simultaneous optimisation of the control inputs and the racing line, making it well-suited for analysing performance when following another car. Extending beyond prior work, the analysis includes cornering scenarios in which aerodynamic wake significantly influences both the trajectory and the vehicle dynamics, thereby affecting overtaking opportunities.

This paper makes the following contributions to wake-aware trajectory optimisation in motorsport:

It integrates wake-dependent downforce, drag, and aerodynamic balance into a spatial-domain optimal control framework, enabling simultaneous optimisation of racing line and control inputs under disturbed aerodynamic conditions.

It extends wake-aware optimal control beyond straight-line slipstreaming by analysing full cornering behaviour, including braking, mid-corner, and traction phases, where wake effects alter both grip and stability.

It applies a telemetry-calibrated Formula 3 planar vehicle model within the Dymos optimal control framework, providing realistic vehicle response while retaining computational tractability.

It quantitatively analyses how optimal racing lines adapt under wake effects, identifying strategies that balance curvature, downforce recovery, and traction to maximise overtaking performance.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows.

Section 2 presents the methodology, including the optimal control problem formulation, vehicle modelling, aerodynamic wake modelling, track generation, and solution strategy.

Section 3 reports the results of the simulations, focusing on overtaking scenarios in both low-speed and high-speed contexts, and discusses their implications in the context of existing literature.

Section 4 provides the conclusions of the study, outlining the main findings, limitations, and directions for future work.

2. Methodology

2.1. Optimal Control Problem Formulation

The primary objective of this study is to determine the time-optimal trajectory of a race car around a prescribed track using optimal control methods. The problem is formulated as an optimal control problem (OCP), in which the objective is to minimise total lap time subject to nonlinear vehicle dynamics and physical constraints on the system.

In this formulation, the optimisation variables are the time histories of the driver control inputs, namely throttle and steering angle, together with the corresponding state trajectories of the vehicle. Throttle directly determines the longitudinal driving force via the engine and drivetrain model, while steering angle governs lateral tyre forces and yaw response. The optimal control problem, therefore, simultaneously determines both the racing line and the actuation required to follow it, subject to nonlinear vehicle dynamics, tyre friction limits, track boundary constraints, and collision avoidance constraints in the dual-car simulations.

An OCP seeks to identify the state trajectories and control inputs that optimise a performance criterion while ensuring that the system evolves consistently with its governing dynamics. In the present formulation, the cost function is lap time minimisation, the system dynamics are defined by a planar three-degrees-of-freedom (DOF) vehicle model, and constraints enforce realistic bounds such as maximum power, track limits, and tyre friction limits.

To transcribe and solve the problem, the Dymos library within the OpenMDAO framework is employed. The optimisation framework is implemented using Dymos (v1.x, OpenMDAO Project, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH, USA) within the OpenMDAO environment (v3.x, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH, USA), which provides automated transcription, derivative computation, and solver interfacing for large-scale optimal control problems. Dymos is a Python-based optimal control tool that implements multiple direct collocation schemes, enabling continuous-time OCPs to be discretised into large-scale nonlinear programming (NLP) problems. It provides flexibility in defining phases of motion, boundary conditions, control parameterisations, and path constraints, making it well-suited for trajectory optimisation in lap-time simulation contexts. In this study, the OCP is transcribed using the Gauss–Lobatto pseudospectral collocation scheme. This method discretises the continuous trajectory into collocation points defined by the roots of Legendre polynomials. At these points, the system dynamics are enforced, while continuity conditions are imposed between successive segments. This approach ensures dynamic feasibility across the trajectory while reducing the continuous OCP to a finite-dimensional NLP. The transcription of the continuous-time optimal control problem into a nonlinear programming problem using direct collocation follows standard practices in trajectory optimisation and numerical optimal control [

14,

15].

The resulting NLP is solved using the Interior Point Optimizer (IPOPT). The resulting nonlinear programming problem is solved using the Interior Point OPTimizer (IPOPT, v3.x, COIN-OR Foundation, Towson, MD, USA). The problem is discretised into 150 segments, each using third-order Gauss–Lobatto polynomials, resulting in a large but tractable optimisation problem. IPOPT iteratively adjusts the control history and corresponding state trajectories to converge to the time-optimal solution.

A critical element of the problem formulation is the choice of the independent variable. While most Dymos examples adopt time as the independent variable, in this study, the state equations are reformulated using arc length along the track centreline as the independent variable:

In this formulation, the independent variable is the distance travelled along the track centreline rather than time. All state derivatives are therefore expressed with respect to track distance, and the vehicle forward speed appears in the equations as the conversion factor between time and spatial progression. This representation ensures that optimisation is performed along the track geometry and avoids difficulties associated with variable lap time during numerical optimisation.

Where is the spatial rate of change in the lateral offset , and is the rate of change in arc length with respect to time (i.e., longitudinal speed along the track). In this spatial formulation, the derivatives represent rates of change with respect to arc length, and the mapping between time and distance is provided by the rate of change in arc length with respect to time, which corresponds to the longitudinal speed along the track. This transformation is applied to all state equations, allowing the dynamics to be expressed in the spatial domain. Using arc length as the independent variable naturally parameterises vehicle progression along the track and avoids issues associated with variable lap time when time is used directly.

Finally,

Table 1 summarises the complete optimal control problem formulation, including control inputs, state variables, path constraints, and the lap time minimisation objective.

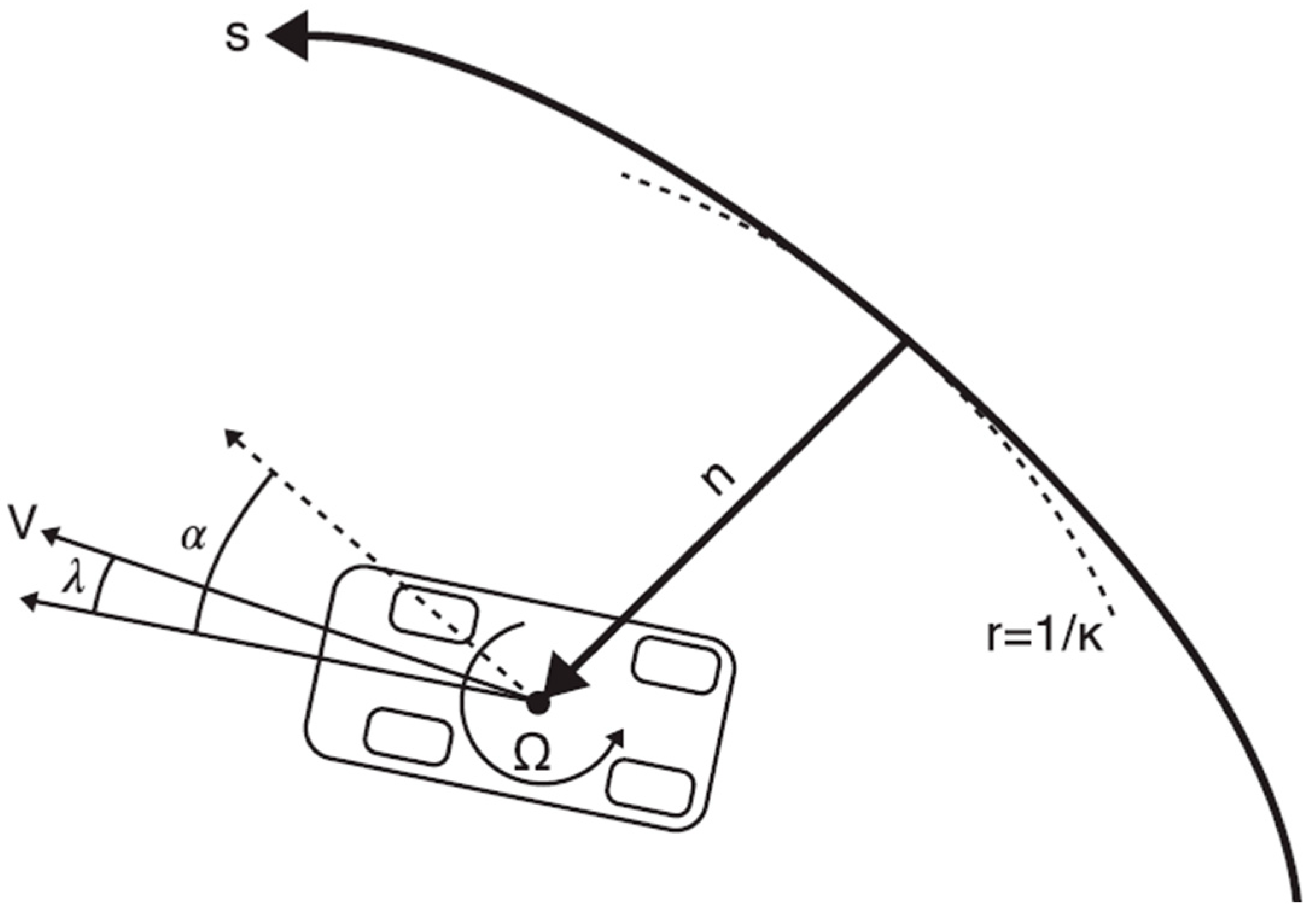

2.2. Vehicle Model

The dynamics of the race car are represented using a planar vehicle model that captures longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motion, following commonly adopted formulations in motorsport trajectory optimisation studies and classical race car vehicle dynamics theory [

8,

16]. This modelling approach provides a balance between physical fidelity and computational efficiency, making it suitable for large-scale optimal control problems. Vertical dynamics, pitch, and roll are not explicitly modelled, consistent with the level of detail required for trajectory optimisation of the FIA Formula 3 car considered in this study. A schematic overview of the vehicle model, coordinate system, and state definitions is shown in

Figure 2.

The governing equations of motion are expressed in the spatial domain and describe the evolution of vehicle speed, yaw rate, heading, and lateral displacement relative to the track centreline. Track curvature is incorporated into the formulation, coupling vehicle orientation and lateral motion to the geometric properties of the circuit. Longitudinal and lateral tyre forces act as the primary contributors to vehicle acceleration and cornering performance.

where

is vehicle speed,

yaw rate,

vehicle heading,

lateral deviation, and κ track curvature. The forces X and Y denote longitudinal and lateral contributions at each tyre.

Tyre behaviour was initially represented using a linear lateral stiffness model dependent on normal load:

with slip angles calculated from geometric relations:

Tyre forces are modelled as functions of slip angle and normal load using a linear load-dependent formulation. Slip angles are computed from vehicle velocity components and yaw motion using standard planar vehicle kinematics. This simplified representation captures the dominant lateral force generation mechanisms while remaining computationally efficient and differentiable for use in optimal control.

Normal loads at each tyre were computed as follows:

Normal loads at each wheel include contributions from static vehicle weight, longitudinal and lateral load transfer, and aerodynamic downforce. Load transfer terms are filtered using first-order dynamics to approximate transient suspension effects while preserving the numerical smoothness required by collocation-based optimisation.

These terms account for static load distribution, longitudinal and lateral load transfer, and aerodynamic downforce. Suspension dynamics are not modelled explicitly; however, transient effects are partially captured by applying time constants to the load transfer equations.

The aerodynamic model assumes constant coefficients for drag, downforce, and aerodynamic balance under free-stream conditions. These coefficients remain fixed except when modified by the wake model of the leading vehicle, as described in

Section 2.3. Variations with ride height, yaw, or pitch are omitted to ensure tractability within the optimal control framework. Data-driven and surrogate modelling approaches, including neural networks and Gaussian process regression, have also been widely used for estimating aerodynamic coefficients when high-fidelity CFD or wind tunnel data are limited [

17,

18,

19].

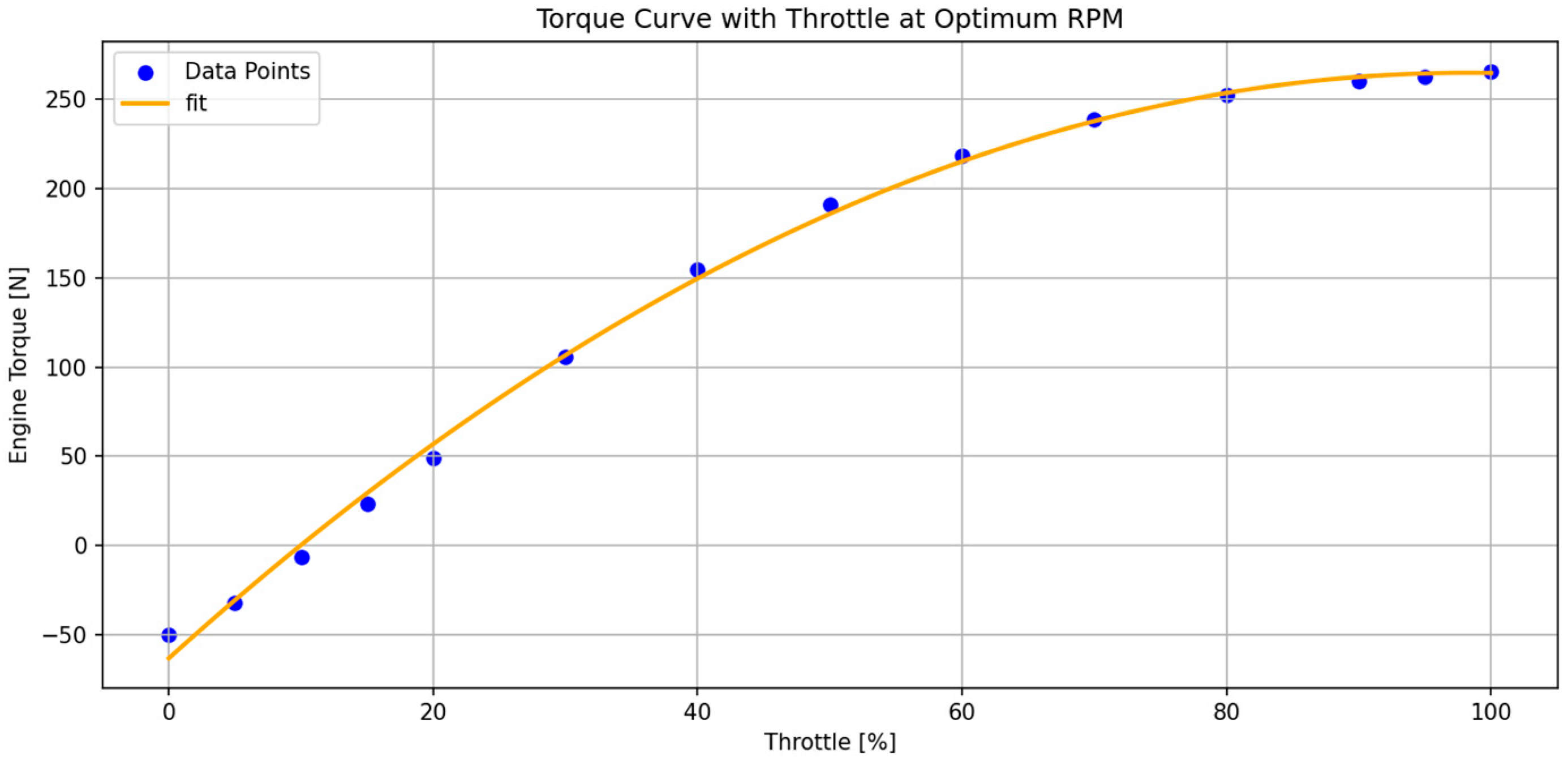

Engine torque data are derived from an AVL-generated Formula 3 engine model (AVL List GmbH, Graz, Austria) and approximated using third-order polynomial fitting in throttle and engine speed to allow smooth integration within the optimal control framework. The variation of engine torque with throttle input and the corresponding polynomial fit are shown in

Figure 3, while the torque variation with engine speed (RPM) and its fitted curve are shown in

Figure 4.

Fitting with 3rd order polynomials:

where for rpm

And for throttle fit

Figure 3.

Engine torque data with throttle input and fitted model.

Figure 3.

Engine torque data with throttle input and fitted model.

Figure 4.

Engine torque data with engine speed and fitted curve.

Figure 4.

Engine torque data with engine speed and fitted curve.

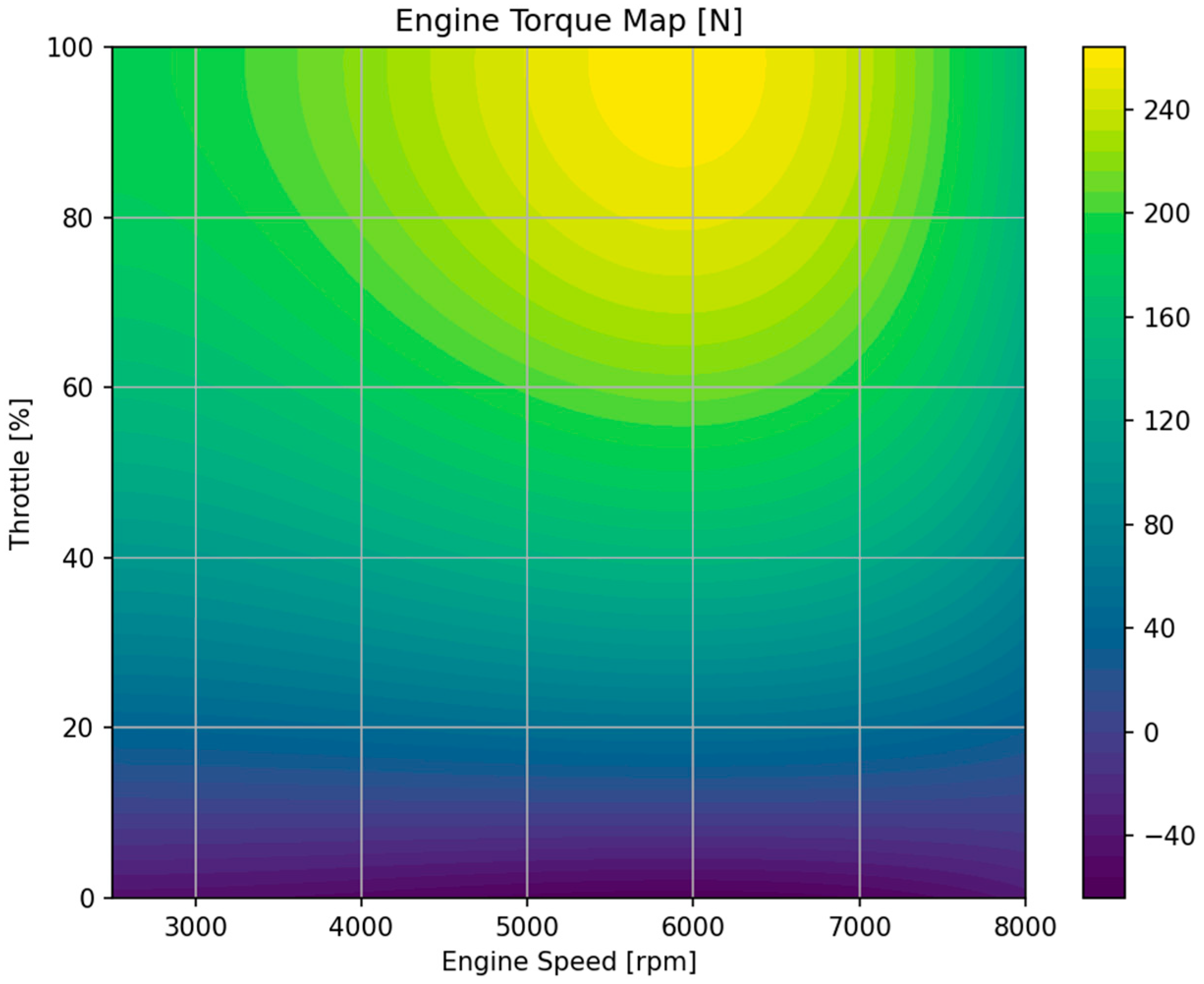

The combined two-dimensional engine torque map as a function of throttle and engine speed, which is used in the vehicle simulations, is shown in

Figure 5.

A third-order polynomial representation was selected as a compromise between fitting accuracy and numerical robustness. Lower-order fits were unable to capture the nonlinear saturation behaviour of torque at high throttle and engine speeds, while higher-order polynomials introduced oscillatory behaviour and increased numerical stiffness in the optimisation problem. Since gradient-based nonlinear programming solvers require smooth and well-conditioned derivatives, the third-order fit provided sufficient accuracy while preserving stability and convergence of the optimal control solution. Similar polynomial approximations are commonly adopted in lap time optimisation studies where differentiability of the drivetrain model is required.

A fixed gear ratio is assumed to avoid the discontinuities associated with discrete gear shifts, which would otherwise complicate the optimisation. Although continuous smoothing functions for gear changes were considered, a constant ratio provides sufficient accuracy for the present study.

Parameter identification is carried out using telemetry from Campos Racing’s 2024 Formula 3 season at the Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya. A baseline F3 model is simulated around the Barcelona layout, starting from known parameter values specified by the FIA Formula 3 regulations [

20]. Key parameters, including tyre stiffness, maximum power, and aerodynamic coefficients, are iteratively adjusted to minimise error relative to measured lap data. This calibration process follows standard nonlinear system parameter estimation methodologies in which model parameters are tuned to minimise discrepancies between measured and simulated responses [

21]. The Barcelona track model used in the simulation predates the 2023 revisions; therefore, only the portion of the lap common to both layouts is considered. Nevertheless, this provides sufficient data to identify the vehicle parameters summarised in

Table 2.

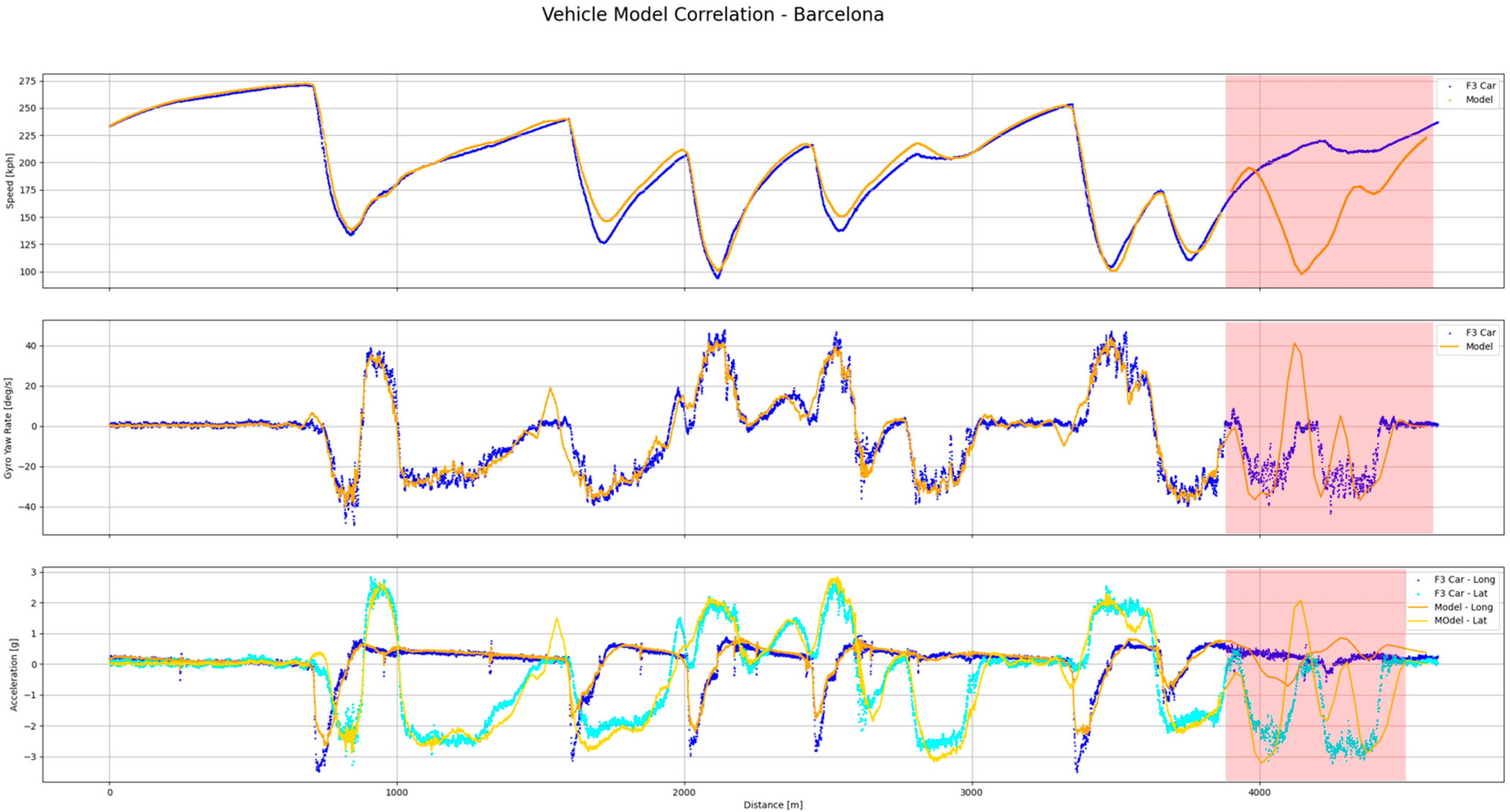

This process produced a calibrated planar model capable of replicating the behaviour of a modern Formula 3 car with sufficient fidelity for optimal control trajectory optimisation, as seen from correlation in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows the correlation between the vehicle model and real telemetry data from a Formula 3 car around the Barcelona circuit. The comparison is presented in terms of vehicle speed, yaw rate, and longitudinal and lateral accelerations. Overall, the model reproduces the main dynamic behaviour of the car, including braking phases, cornering behaviour, top speeds, and acceleration levels, with reasonable accuracy. The speed trace demonstrates close agreement on the straights, in major braking zones, and through most corners. However, discrepancies are observed at Turns 4, 6, and 7, where the model exhibits greater grip than the real vehicle. These deviations are likely attributable to the simplified tyre and aerodynamic formulations adopted. Nevertheless, the correlation is considered sufficient to identify and tune the primary vehicle parameters, ensuring that the model represents the dynamics of a modern Formula 3 car with adequate fidelity for optimal control simulations.

The quantitative correlation between the simulated vehicle model and the measured telemetry data is summarised in

Table 3, reporting the root-mean-square error (RMSE) values for vehicle speed, yaw rate, and longitudinal acceleration.

These metrics are obtained before reaching the track distance of 3870 m, where the simulation and telemetry data layouts are different, as indicated in

Figure 6 with the regions in red. At this location, the real car lap time is 75.540 s while the simulation lap time is 71.466 s. This is a big but acceptable difference given the simplified linear tyre model applied in the simulation, which enhances the performance envelope, as well as other simplifications like the suspension of the aerodynamic coefficients being independent of attitude.

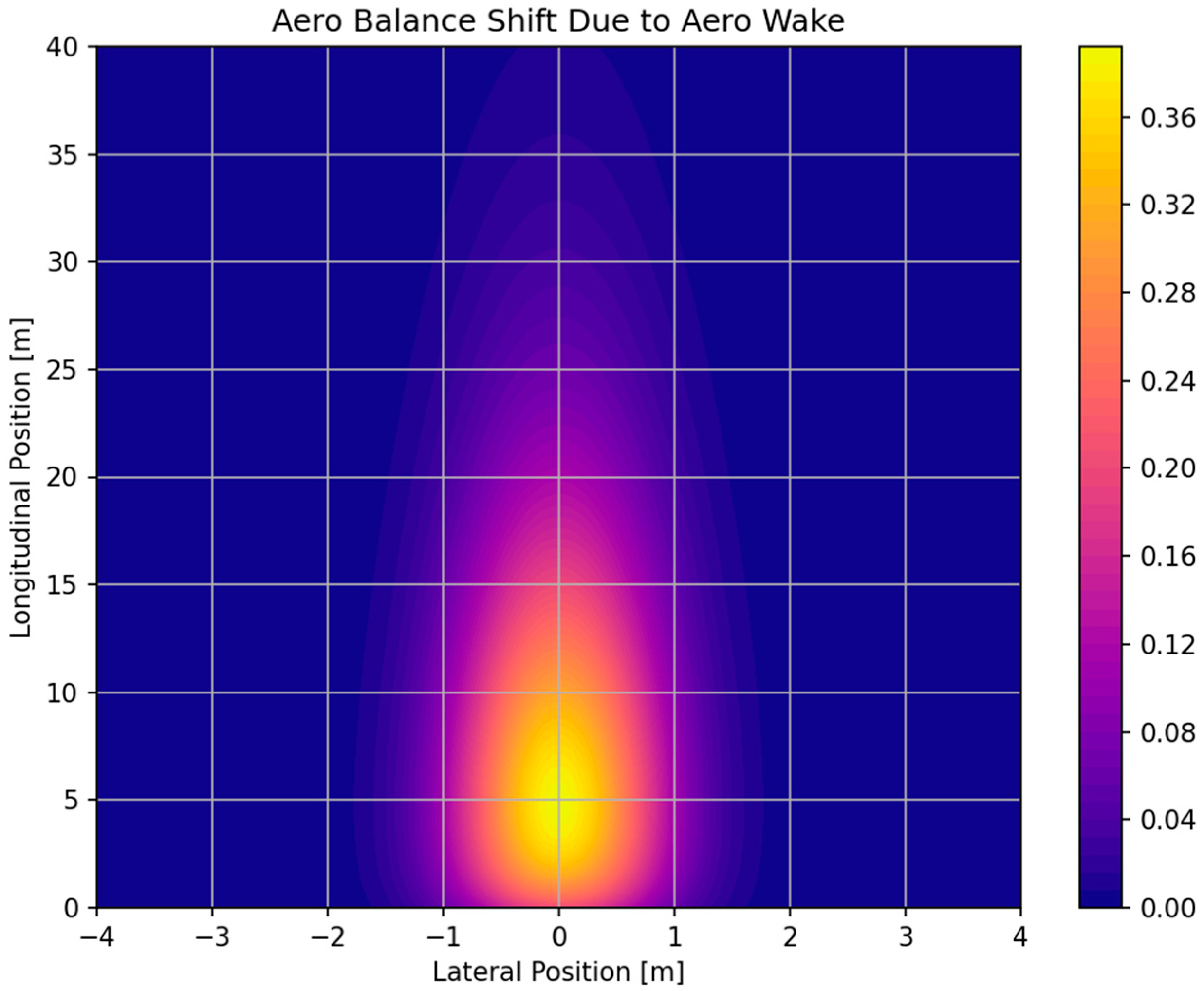

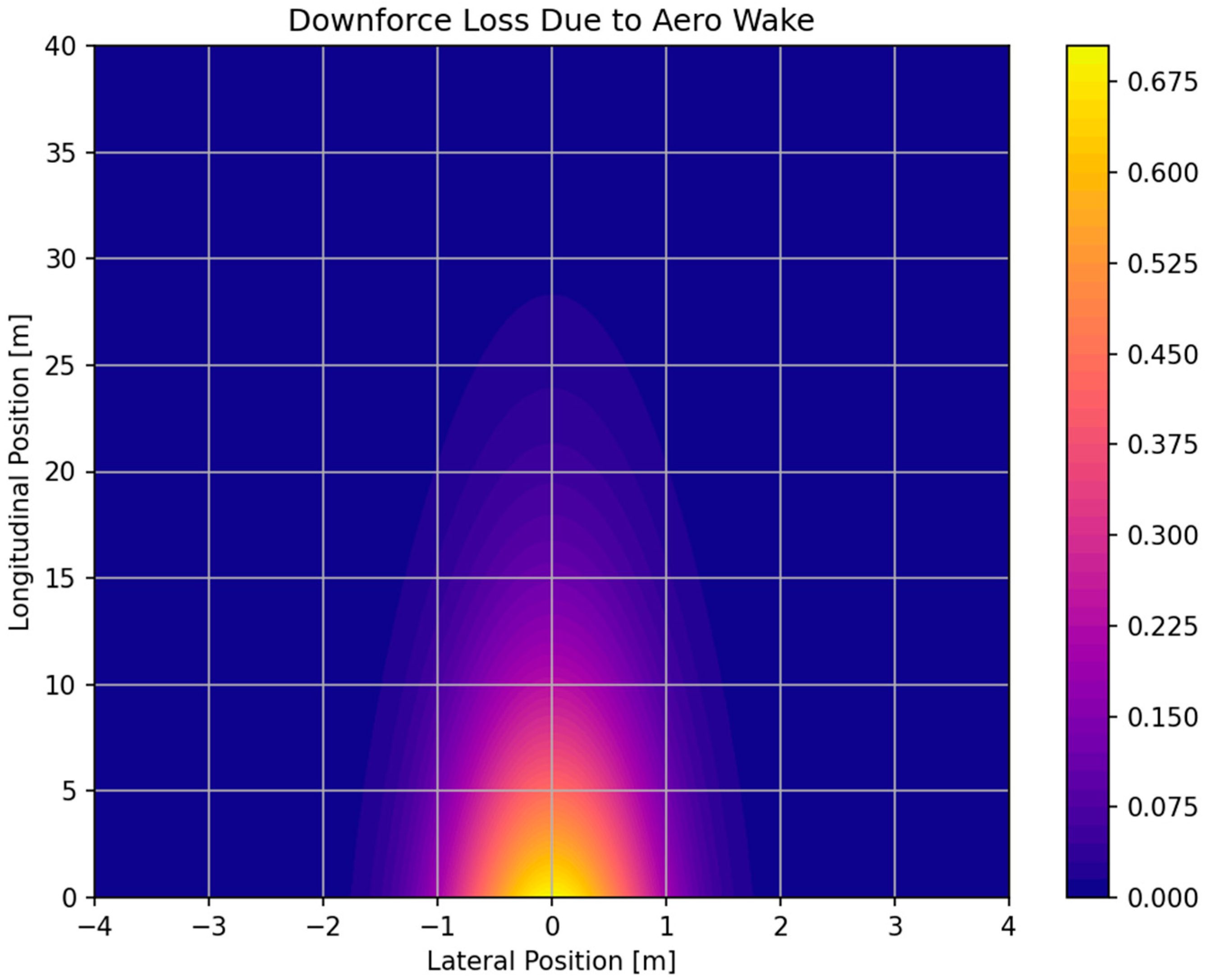

2.3. Aerodynamics Wake Model

Because the objective of this study is to investigate overtaking manoeuvres under disturbed flow conditions, it is essential to adopt a model capable of capturing the aerodynamic losses experienced by a trailing car in the wake of a leading vehicle. To incorporate these effects within the optimal control framework, a spatially varying wake model is derived based on experimental and simulation data reported in the literature [

2,

3,

4]. These studies consistently show that the wake of an upstream vehicle leads to reductions in downforce and drag, as well as shifts in aerodynamic balance for the following car, with the magnitude of the disturbance depending on the relative longitudinal spacing and lateral offset. Maximum disturbance occurs when the trailing car is directly behind the leader at small longitudinal gaps. The effects decay both as the separation distance increases and as the following car moves laterally away from the wake centreline.

The wake model follows the structure proposed by [

3] and is adapted to include explicit effects on aerodynamic balance in addition to downforce and drag. Gaussian process regression and similar surrogate modelling tools are frequently employed for constructing aerodynamic response surfaces and wake-related loss maps in situations where dense experimental or CFD datasets are unavailable [

19,

22]. The aerodynamic losses are defined by Equation (9).

In this formulation, wake effects are applied as multiplicative loss factors to the baseline aerodynamic coefficients of the following car, thereby directly modifying the resulting aerodynamic forces. Specifically, drag and downforce coefficients are reduced according to the wake loss maps as functions of longitudinal and lateral separation, and aerodynamic balance is shifted accordingly. The wake model does not act on engine power or drivetrain output; rather, it alters the aerodynamic force generation that governs braking, cornering, and traction performance. The notation has therefore been clarified to reflect force and coefficient modification rather than power reduction.

Where

is the lateral offset, therefore

represents the normalised loss when the longitudinal distance is 0 between the cars,

is the longitudinal spacing between the vehicles, and

the maximum possible loss for each aerodynamic parameter. The lateral decay of the wake is represented in Equation (10):

where

is the upstream vehicle speed, and

and

are calibration constants chosen to match trends observed in the literature, with

The longitudinal decay is captured by separate functions for downforce, drag, and for aero balance, as given in Equations (11) and (12), respectively.

The aerodynamic loss functions depend on the relative longitudinal spacing and lateral offset between the vehicles. Maximum losses occur when the following car is directly behind the leading car at short distances, while losses decay as separation increases or as the following car moves laterally away from the wake core. This formulation captures the first-order spatial structure of wake disturbances in a computationally efficient and differentiable manner.

The maximum magnitudes of the wake losses were set as 70% for downforce, 42% for drag, and 20% for aero balance, consistent with findings from [

2,

4]. These values correspond to the extreme case of very close following along the leader’s centreline.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate the resulting loss maps for aerodynamic balance, drag, and downforce at a reference speed of 50 m/s. The disturbance is most severe in the near wake, where downforce losses exceed 60%, and significant shifts in aerodynamic balance occur. As spacing increases beyond approximately two to three car lengths, the disturbance diminishes rapidly. Lateral offsets further reduce the effect, with the trailing car recovering nearly full aerodynamic performance once positioned outside the main wake core.

Within the vehicle dynamics model, this wake formulation is applied as a set of correction factors to the baseline aerodynamic coefficients of the trailing car. Specifically, the downforce and drag coefficients are reduced according to their corresponding loss maps, and aerodynamic balance is shifted by adding the map-based deviation to the baseline free-stream value. Because the functions are continuous and differentiable, they can be directly evaluated within the collocation-based OCP without introducing discontinuities or solver instability. This enables computationally efficient optimisation while remaining grounded in experimental evidence.

Several simplifications are inherent to this approach. First, the model is quasi-steady, depending only on instantaneous longitudinal and lateral spacing, and does not account for time-dependent turbulence or vortex shedding. Second, variations in wake structure with yaw angle, ride height, or crosswind conditions are neglected. Despite these limitations, the chosen formulation captures the first-order aerodynamic consequences of wake interaction, providing sufficient fidelity for the purpose of overtaking trajectory optimisation.

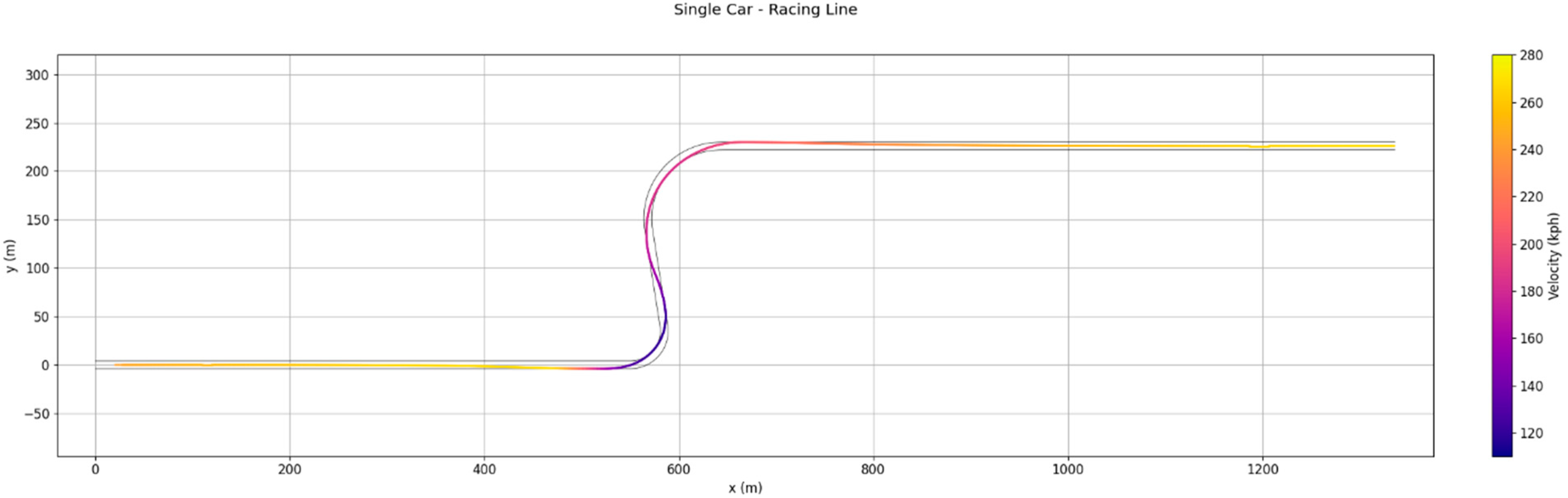

2.4. Track Generation

For this study, a customised track is generated to balance realism with computational efficiency. Since the simulations involve solving large-scale optimal control problems with additional aerodynamic wake and collision constraints, a short open layout is selected to reduce computational load while still capturing the key racing scenarios relevant to overtaking and following a car in the wake. The track configuration is designed to include both a low-speed corner and a medium-to-high-speed corner connecting two straights. This design enables investigation of two distinct overtaking contexts: (1) the heavy braking zone at the end of the first straight leading into a tight corner, representing a classical overtaking opportunity, and (2) a faster, more aerodynamically sensitive second corner, where reduced downforce due to wake effects plays a critical role in determining available grip and corner-exit speed. This track design captures both mechanical and aerodynamic limitations, providing a relevant test case for the overtaking simulations.

Figure 10 shows the resulting racing line obtained for the single-car simulation, with velocity distribution mapped along the trajectory.

The layout consists of the following segments: (1) a 550 m straight, (2) a 35 m radius corner with a sweep angle of , representing a low-speed corner following the first straight, (3) a 100 m straight, (4) a 75 m radius corner with a sweep angle of , and (5) a 700 m straight where overtaking manoeuvres can be completed. The circuit is defined programmatically using Dymos track generation utilities. The track is represented as an ordered sequence of parametric segments, each described by four parameters: type (straight or corner), length or sweep angle, radius, and direction (left or right).

This compact parametric representation is then passed to a custom Track class, which generates the continuous centreline, curvature distribution, and orientation data required for the simulation. These quantities are subsequently used to enforce track boundary constraints in the optimal control problem and to evaluate vehicle dynamics along the circuit.

2.5. Solution Strategy

The solution strategy adopted in this study follows a sequential two-step approach. First, a reference trajectory is generated by solving a single-car optimal control problem to obtain the minimum-time trajectory for a Formula 3 vehicle around the track under free-stream conditions. This trajectory is referred to as the ghost car. Second, using the ghost trajectory as an input for the attacking vehicle, a dual-car simulation is performed in which the active car experiences aerodynamic wake effects and must determine an alternative optimal racing line that maximises performance under disturbed flow while avoiding contact with the leading vehicle during overtaking manoeuvres [

3].

The single-car problem is solved after the vehicle model has been parameterised and correlated with Campos Racing telemetry. The resulting solution provides the theoretical minimum-time lap for the given car–track configuration, including the optimal racing line, velocity profile, and control history. This trajectory serves as the fixed reference for the leading vehicle in all subsequent dual-car simulations. The ghost car is assumed to remain on this trajectory without defensive manoeuvres, consistent with the assumptions adopted in [

3].

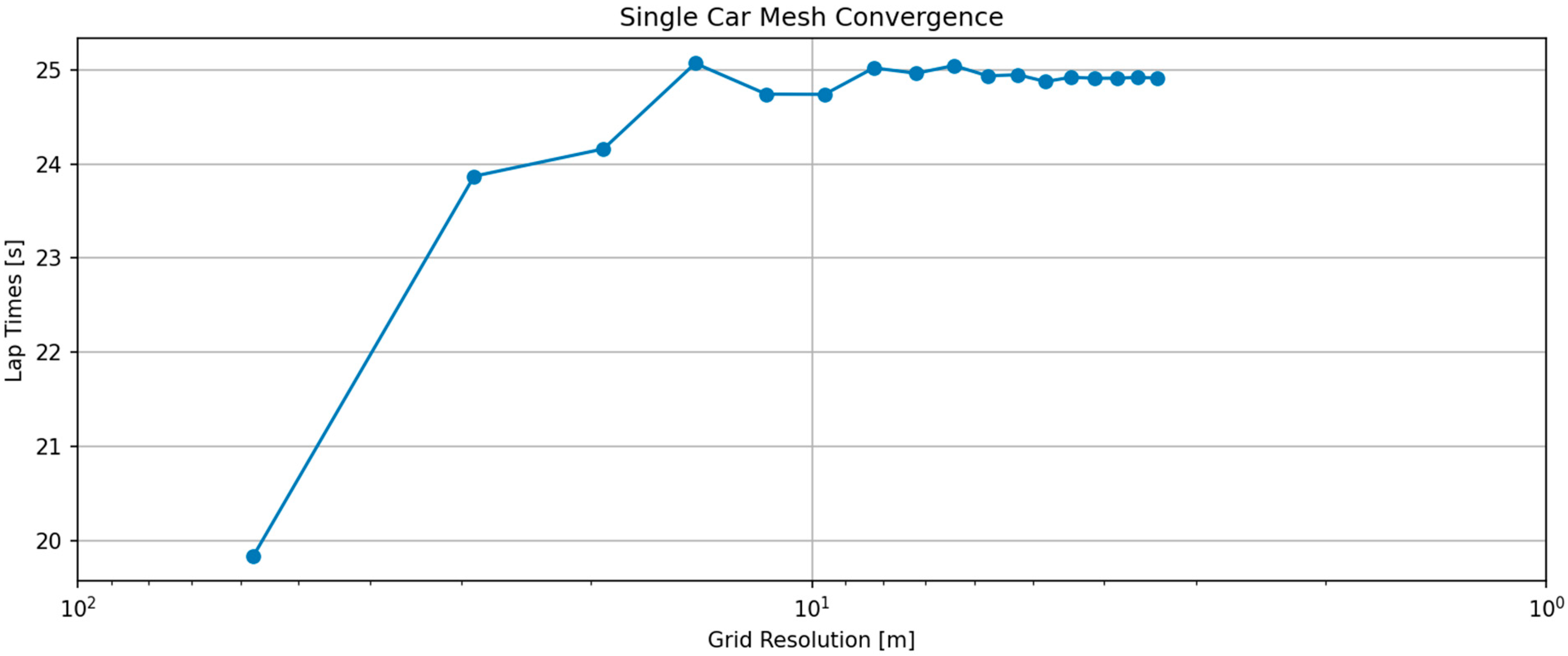

A mesh independence study was conducted for the single-car case. Based on this analysis, 150 segments with three nodes per segment (third-order Legendre) were selected, corresponding to the mesh-independent region. This discretisation also provides sufficient resolution to capture the additional complexity introduced by the aerodynamic wake model and collision constraints. The mesh convergence behaviour and the resulting independence of lap time with respect to grid spacing are illustrated in

Figure 11.

The second step introduces the active car, which begins its lap from behind the ghost car. The active car’s dynamics are modified by the wake model described in

Section 2.3, reducing available downforce and drag as a function of relative spacing. This ensures that the active vehicle experiences the aerodynamic penalties observed in real racing when following closely.

To prevent unrealistic overlap with the ghost trajectory, a collision avoidance constraint was formulated with Equation (13). The constraint ensures that the active car’s trajectory always remains outside the collision zone surrounding the ghost car, in both the longitudinal and lateral directions.

Here, represents the longitudinal position along the track centreline and the lateral offset, while the hyperbolic and sigmoid functions smooth the exclusion zone to ensure differentiability. This formulation is critical, as the OCP requires constraints that are at least C1 continuous to allow gradient-based Hessian evaluation. The resulting inequality constraint is applied in the spatial domain, with dynamics evolving along the track depending on the longitudinal spacing between the cars. The required lateral offset increases as the minimum lateral distance between the cars decreases and relaxes to zero when the spacing is sufficiently large.

Once both wake effects and collision constraints are implemented, the active-car simulations are performed. By construction, these simulations can be interpreted as dual-car optimal control problems in which the ghost car is fixed and the active car searches for a feasible minimum-time trajectory around it.

The primary goal of this study is to investigate overtaking in two regions of the track: first, at the end of the first straight, where a low-speed corner follows a heavy braking zone, representing a natural overtaking opportunity in real racing; and second, at the end of the second straight, after a high-speed corner where aerodynamic effects dominate grip and traction. To trigger successful overtakes in these regions, the active car is given a performance advantage by increasing its grip to represent a pace advantage. The initial speed and position of the active car are adjusted accordingly to position the vehicle appropriately relative to the ghost car at the onset of the overtaking manoeuvre.

The choice of increased grip reflects observations from the article in the Canopy Simulations Blog, a recent study on the fundamentals of overtaking, which highlights that overtakes rarely occur between cars of identical pace. Grip, therefore, serves as a reasonable proxy for this advantage. This work also emphasises the sensitivity of overtaking performance to aerodynamic wake, confirming that stronger wake effects reduce overtaking feasibility [

5]. These insights align with the rationale of this project, which aims to explore how the optimal racing line adapts to minimise the negative influence of wake when following another car.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Straight 1 Overtake

In this section, a second active-car simulation is presented in which vehicle dynamics are affected by the trajectory of the ghost car. The ghost car remains on the minimum-time trajectory obtained from the single-car simulation, while the active car adapts its racing line to exploit aerodynamic effects and avoid collision with the leading vehicle. This behaviour is not present in the single-car case, where the minimum-time trajectory is obtained without wake interaction. In the dual-car scenario, the active vehicle modifies its trajectory to avoid collision with the ghost car, as enforced by the collision constraint described in

Section 2.5.

The first overtaking case is configured to occur in the braking zone before Turn 1 (T1). To enable the manoeuvre at this location, the initial conditions of the active car are adjusted. The active car is started 10 m behind the ghost car, matching its initial speed of 68 m/s. Moreover, the active car is given a 5% increase in tyre grip, representing a performance advantage. These conditions replicate realistic overtaking scenarios in Formula 3, where overtakes typically require a grip or pace advantage.

The results show behaviour consistent with real-world racing. On the straight preceding Turn 1, the active car follows closely in the wake of the ghost car, experiencing a reduction in drag but also a significant loss of downforce. As the braking zone is approached, two critical changes occur. First, the active car moves laterally away from the ghost car in order to comply with the collision constraint and initiate the overtaking manoeuvre. Second, this lateral displacement allows the active vehicle to exit the wake at the precise moment when maximum braking performance is required.

This timing is crucial because braking capability is strongly dependent on available aerodynamic downforce, which is degraded within the wake. Under wake conditions, both downforce and aerodynamic balance are reduced, degrading stability and braking performance. By moving laterally out of the wake immediately before braking, the active car regains clean airflow, enabling stronger braking compared to the ghost car and facilitating the overtake under improved grip and aerodynamic conditions.

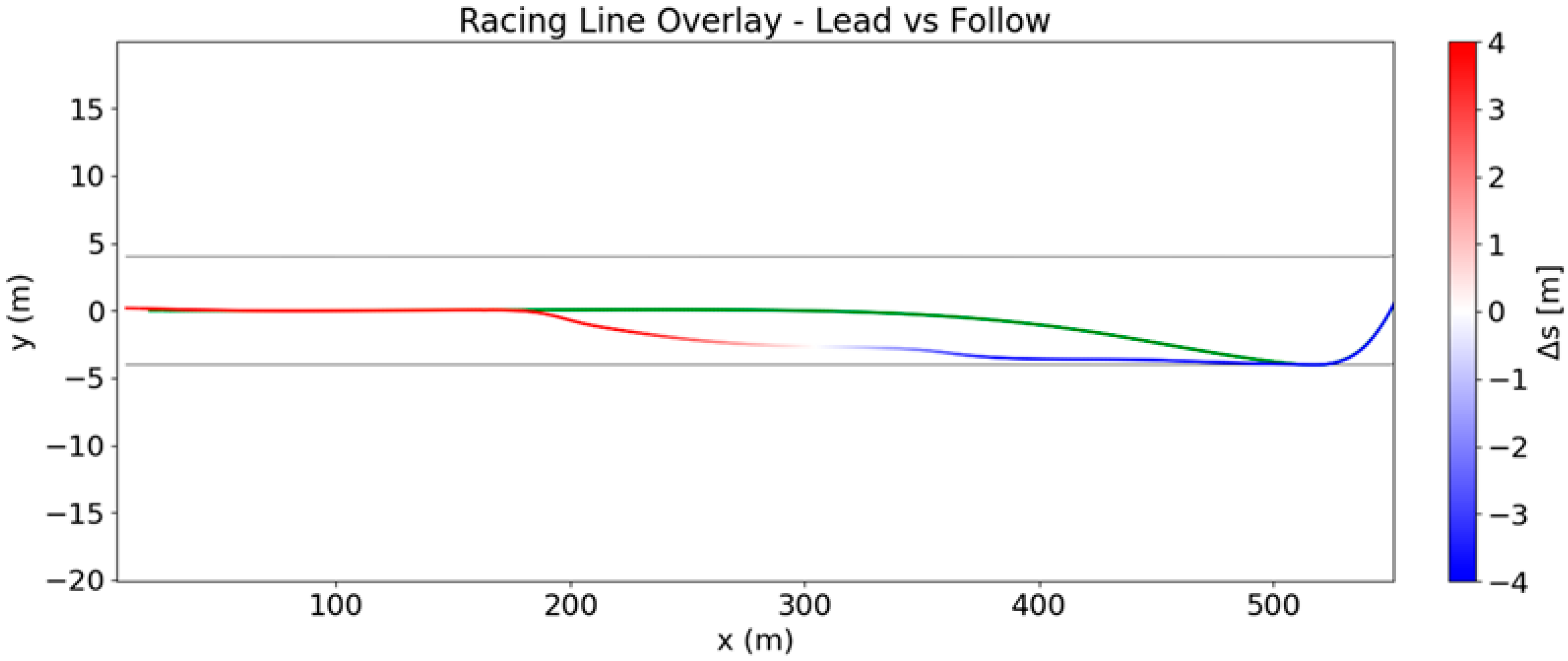

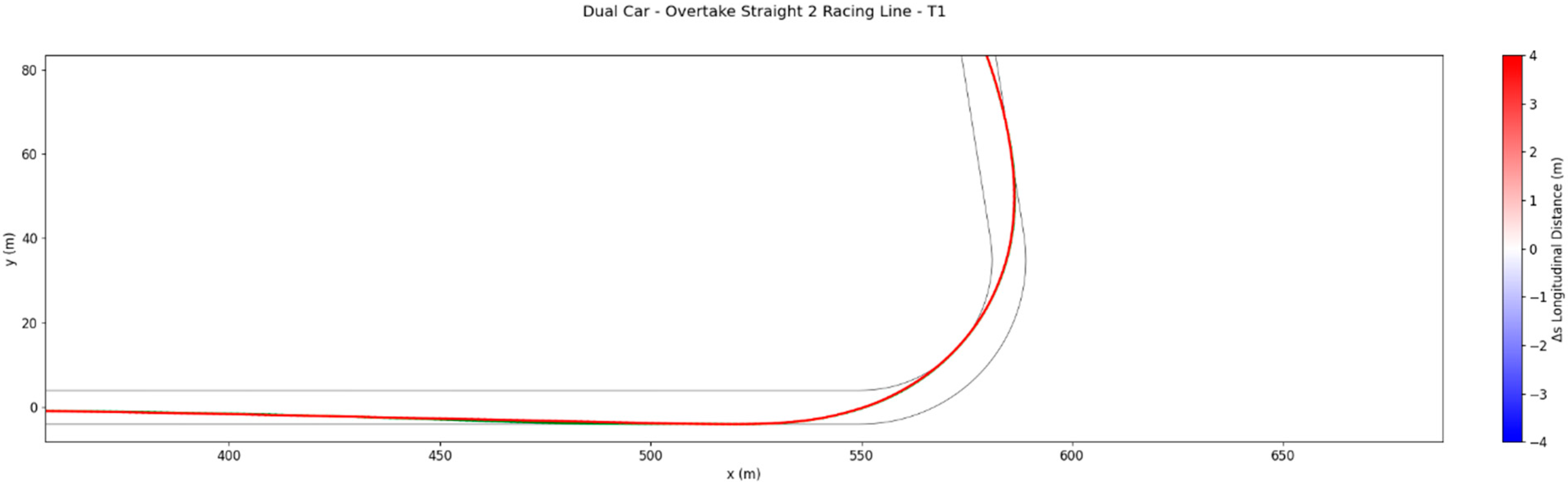

The results from

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show a successful overtake at the entry to Turn 1, achieved by combining slipstream-induced drag reduction on the straight with restored aerodynamic performance under braking. In

Figure 12, the ghost car trajectory is shown in green, while the active car trajectory is coloured by longitudinal spacing relative to the reference car, with red indicating that the active car is behind and blue indicating that it is ahead.

This timing reflects overtaking behaviour commonly observed in practice: cars follow closely in the wake to maximise drag reduction and then deliberately move laterally out of the wake under braking to avoid instability and recover braking performance. The simulation, therefore, captures a key physical mechanism governing overtaking in modern Formula racing.

3.2. Straight 2 Overtake

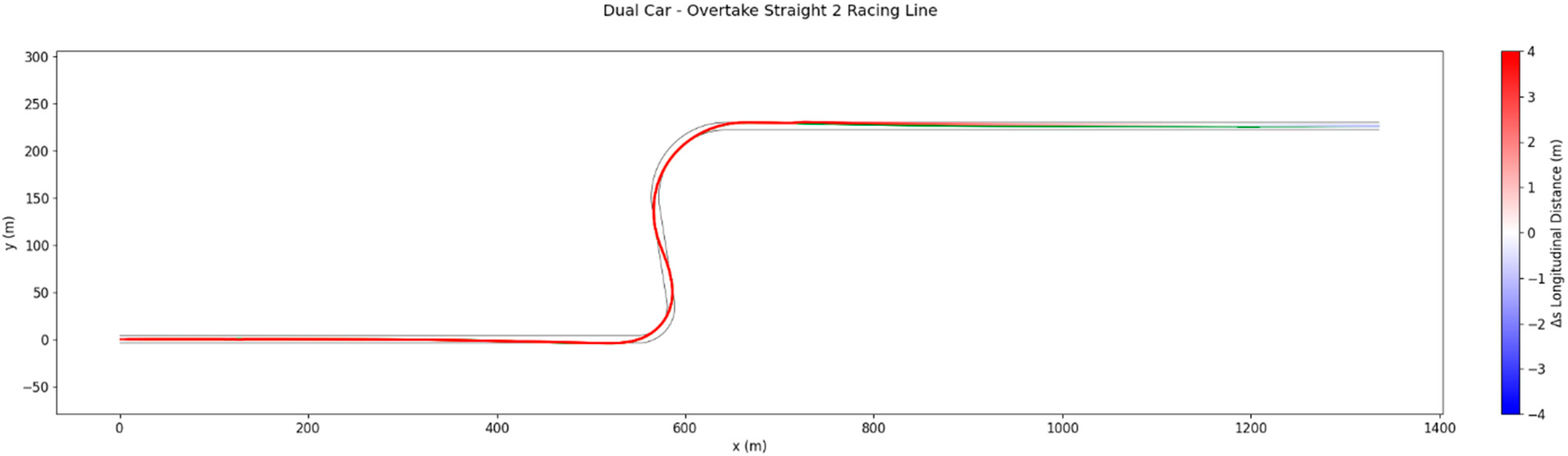

The second overtaking case is configured to occur on the back straight following the medium-speed Turn 2. The active car is assigned a 5% grip advantage and initial conditions of and /s. This setup places the active car close enough to benefit from slipstream on the first straight, but not sufficiently close to complete the overtake immediately, requiring the vehicle to follow the ghost car through the corners before attempting the pass.

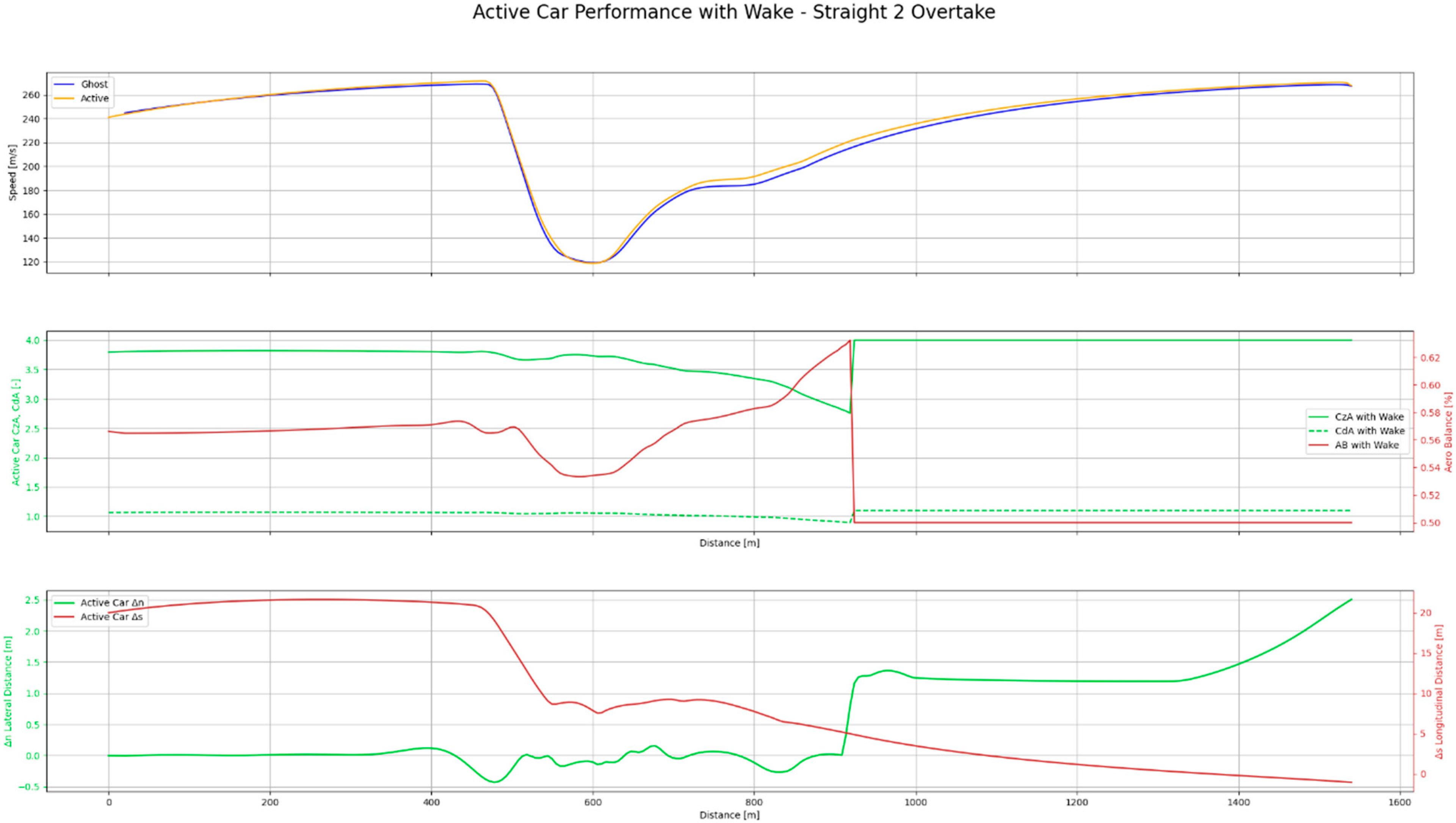

Figure 14 presents the results of this case, showing the speed profiles of both cars, aerodynamic coefficients, and aerodynamic balance in both longitudinal and lateral directions along the track. In the second subplot, it is observed that both downforce and drag decrease exponentially as the ghost car enters the wake of the leading vehicle and then recover as the active car exits the wake to perform the overtake. In the third subplot, the evolution of the aerodynamic balance is shown, which has a direct effect on traction performance, as tyre load distribution is highly dependent on the aerodynamic load acting on the rear axle.

In the final subplot, the evolution of the relative position of the active car with respect to the ghost car is shown. The active car gradually closes the gap on Straight 2, with spacing decreasing significantly through Turn 1 braking and the subsequent corner, until the overtake is completed on Straight 2. In green, the lateral offset of the racing line used by the active car relative to the ghost car is also shown, providing insight into where lateral displacement is required to maximise grip and traction.

The behaviour of the active car demonstrates how the optimal control solution balances lateral racing-line deviations with downforce recovery, dynamically adjusting the trajectory to maximise performance under wake-affected aerodynamic conditions.

During the first straight, the active car maintains an trajectory, staying perfectly in line with the ghost car in order to maximise drag reduction and close the gap. This behaviour reflects the classical slipstreaming strategy observed in open-wheel racing.

As the braking zone into Turn 1 is approached, the active car deviates laterally by approximately 0.5 m, partially exiting the wake, as shown in

Figure 14. This lateral displacement restores aerodynamic downforce and improves braking stability, consistent with the discussion of the previous overtaking scenario. The limited offset suggests a trade-off: fully leaving the wake would increase downforce further but would also require a wider racing line, increasing path length and reducing drag benefit. Instead, the optimisation balances drag reduction with sufficient downforce recovery, resulting in a compromise trajectory.

As expected, wake-induced downforce loss penalises the active car in Turn 1, producing lower cornering speeds relative to the ghost vehicle. At late entry and mid-corner, the trajectory is shifted outward by approximately 0.12 m, increasing lateral grip at corner exit. This offset allows partial recovery of downforce and shifts aerodynamic balance rearwards, improving traction and exit stability. These adjustments are reflected in small gains in downforce and significant recovery in aerodynamic balance, as shown in

Figure 15.

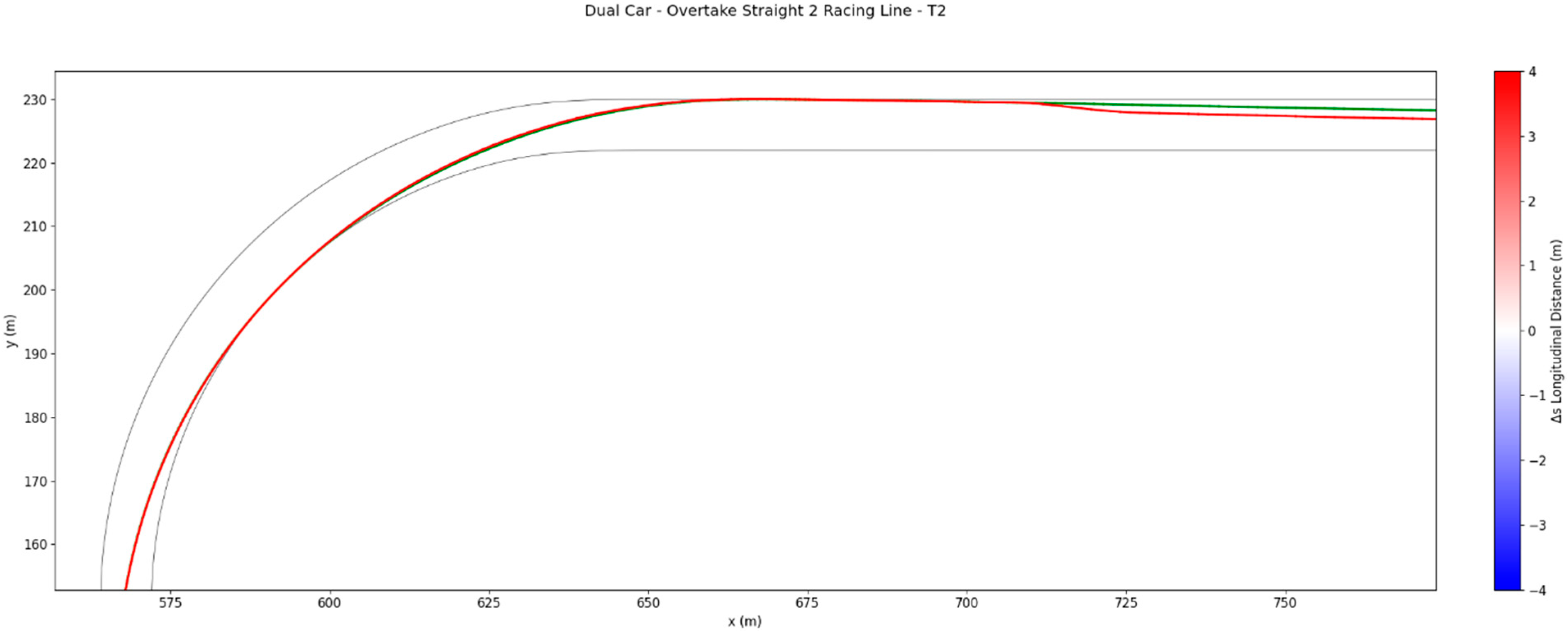

Through Turn 2, the racing line remains broadly similar to that of the ghost car, but another lateral deviation occurs at the exit. The active car shifts outward by approximately 0.26 m away from the ghost’s wake, again improving downforce and restoring a more favourable aerodynamic balance for traction. This manoeuvre sets up the subsequent overtaking attempt on the following straight by maximising exit speed.

With the slipstream advantage regained on the subsequent straight, the active car applies the same principles as in the first overtaking scenario. It aligns closely with the ghost car to maximise drag reduction, increasing speed relative to the leader. Once the collision constraint becomes active, the active car moves laterally to avoid overlap while conserving momentum, completing the overtake before the end of the straight, as shown in

Figure 16.

Overall, this case demonstrates the dual influence of aerodynamic wake, penalising performance in corners while simultaneously enabling slipstream gains on the straights. The optimised racing line exhibits small but deliberate deviations from the ideal single-car racing line in order to balance these competing effects. The results are consistent with observations in Formula 3 racing, where overtakes typically occur after a sequence of wake-induced compromises in cornering phases, followed by decisive slipstreaming on the subsequent straights. These results highlight the importance of maximising traction at corner exit when operating within the wake of a leading vehicle.

3.3. Quantitative Assessment of Wake Effects and Performance Trade-Offs

Although the primary objective of this study is to demonstrate wake-aware trajectory optimisation, quantitative indicators were extracted from the simulation outputs presented in

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 to assess the magnitude of aerodynamic and performance effects during overtaking.

From the aerodynamic coefficient histories shown in

Figure 14, the active car experiences peak downforce losses exceeding approximately 50–60% when following directly behind the ghost car at short longitudinal gaps. Drag reduction in these regions is of similar order, consistent with the wake loss maps presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. These reductions persist through braking and corner entry phases until the active car deviates laterally from the wake core.

During braking into Turn 1, the speed traces indicate that the active car initially retains a higher approach speed due to slipstreaming, but recovers aerodynamic load shortly before peak deceleration by exiting the wake. As a result, the minimum corner entry speed remains close to that of the ghost car, while avoiding excessive braking distance. This behaviour is visible in the convergence of speed profiles in

Figure 14 around the braking phase.

In the mid-corner and exit of Turn 1, wake-induced downforce loss reduces lateral grip and limits achievable cornering speed. However, small lateral deviations of approximately 0.1–0.3 m, visible in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, allow partial recovery of downforce and a rearward shift in aerodynamic balance, which improves traction performance. The exit speed of the active car from Turn 2 is therefore slightly higher than that of the ghost car, producing a longitudinal speed advantage entering the second straight.

On Straight 2, the longitudinal spacing plot in

Figure 14 shows a monotonic reduction in gap, confirming that the combined effect of increased exit speed and drag reduction enables continuous closing of the distance to the lead vehicle. The overtake is completed before the next braking zone without violating track boundaries or collision constraints.

Overall, the quantitative indicators extracted from the simulation outputs demonstrate that wake effects impose substantial penalties in cornering phases while providing significant benefits on straights. The optimal control solution balances these competing effects by adjusting the racing line and control inputs to maximise net time gain, which is consistent with observed overtaking strategies in real Formula racing.

3.4. Comparison with Previous Overtaking and Trajectory Optimisation Approaches

Previous studies on race-car overtaking and interaction have largely focused on either straight-line slipstream benefits or on collision avoidance strategies using predictive control, without explicitly optimising the racing line under aerodynamic wake disturbance. For example, Liu et al. [

3] formulated an optimal control problem including wake-induced drag and downforce reduction but primarily analysed overtaking feasibility on straight segments, where the dominant effect of the wake is drag reduction and acceleration benefit. In such cases, the optimal strategy is mainly to remain aligned with the leading car to maximise slipstream gains.

By contrast, the results of the present study demonstrate that when full cornering dynamics are included, wake effects fundamentally alter the optimal racing line through braking, mid-corner, and corner-exit phases. In both overtaking scenarios, the active car deviates laterally from the ghost trajectory prior to peak braking and at corner exit to recover downforce and achieve a more favourable aerodynamic balance for traction. This behaviour cannot be captured by straight-line slipstream models or by quasi-steady lap time simulation approaches that assume a fixed racing line and steady-state cornering.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) and game-theoretic racing studies typically prioritise collision avoidance and strategic positioning rather than minimum-time trajectory optimisation under detailed aerodynamic disturbance. In such formulations, wake effects are often simplified or neglected, and racing lines are frequently discretised into predefined lanes or corridors. While these methods are effective for real-time planning and safety, they do not explicitly capture how aerodynamic wake modifies optimal path curvature and traction limits throughout the cornering sequence.

The present optimal control formulation, therefore, complements existing approaches by directly coupling wake-dependent aerodynamic coefficients with vehicle dynamics and spatial-domain trajectory optimisation. This allows the racing line itself to become an optimisation variable, revealing subtle but performance-critical lateral adjustments that balance curvature penalties against aerodynamic recovery. The observed strategies, such as exiting the wake before braking and prioritising traction recovery at corner exit, align with empirical racing practices but are rarely produced by simplified overtaking or traffic-style interaction models.

Overall, compared with prior straight-line slipstream analyses and predictive collision-avoidance frameworks, the proposed method provides deeper insight into how aerodynamic wake reshapes the entire overtaking trajectory rather than only influencing acceleration on straights. This highlights the importance of integrating full vehicle dynamics and wake-sensitive aerodynamics within optimal control when analysing overtaking performance in motorsport.