Towards Stable Training of Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Holomorphic Initialization Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Initialization Principles in Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks

2.1. Initialization Theory in PINNs

2.2. Generalized Initialization Strategy for Complex-Valued Networks

2.3. Empirical Estimation of Gain Parameters

3. Experimental Validation on Differential Equation Benchmarks

3.1. Undamped Complex Helmholtz Equation

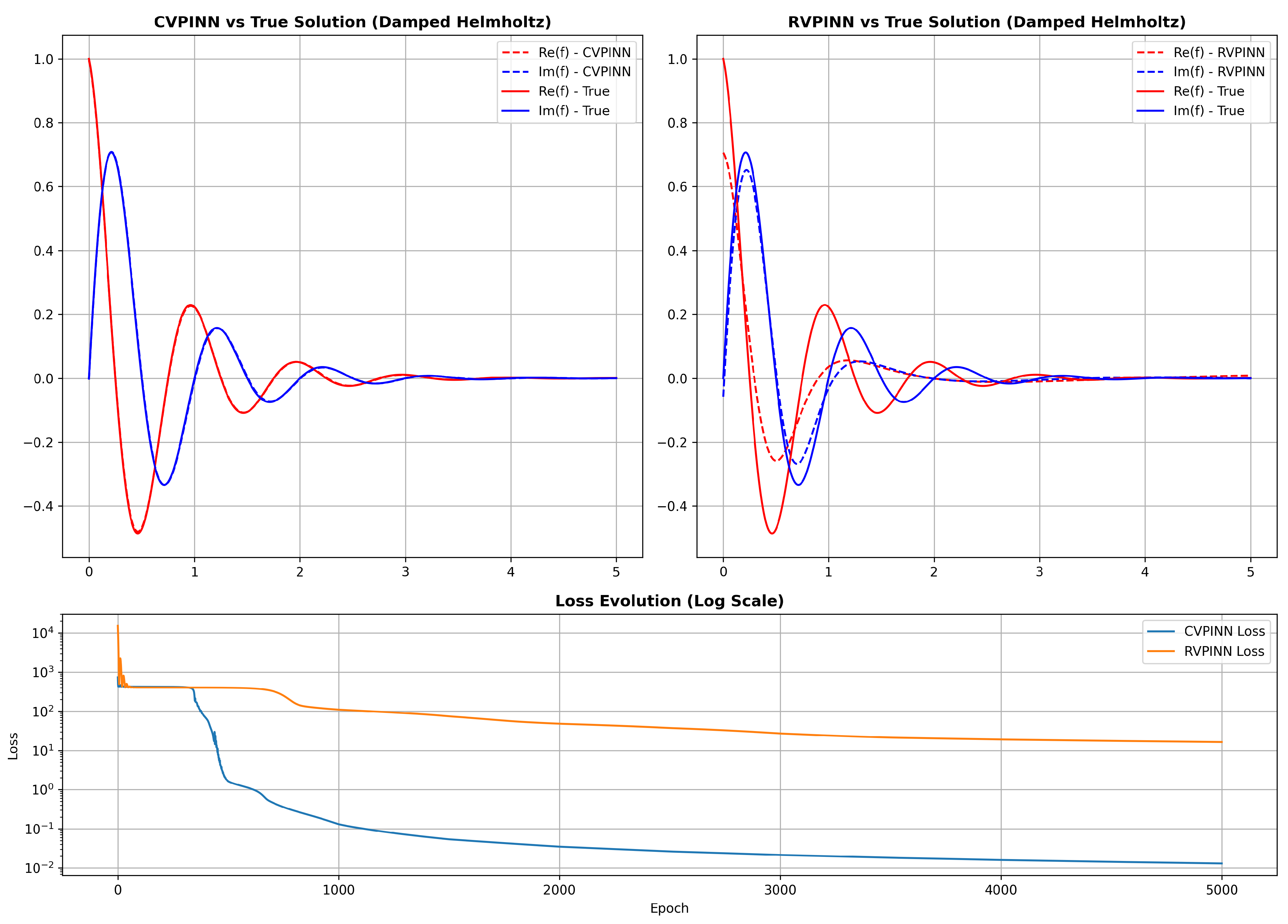

3.2. Damped Complex Helmholtz Equation

3.3. Forced Complex Helmholtz Equation

3.4. Two-Dimensional Helmholtz Equation Simulation

- The PDE residual inside the domain. For the CVPINN, this isFor the RVPINN, the complex PDE is split into two coupled real equations for the real and imaginary components.

- The boundary condition residual is

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control. Signals Syst. 1989, 2, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, T.; Girosi, F. Networks for approximation and learning. Proc. IEEE 1990, 78, 1481–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaris, I.; Likas, A.; Fotiadis, D. Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial differential equations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaris, I.; Likas, A.; Papageorgiou, D. Neural-network methods for boundary value problems with irregular boundaries. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2000, 11, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kang, I.S. Neural algorithm for solving differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 1990, 91, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2017, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Rev. 2021, 63, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, E.; Juanes, R. SciANN: A Keras/TensorFlow wrapper for scientific computations and physics-informed deep learning using artificial neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 373, 113552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sondak, D.; Protopapas, P.; Mattheakis, M.; Liu, S.; Agarwal, D.; Di Giovanni, M. NeuroDiffEq: A Python package for solving differential equations with neural networks. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Molinaro, R. Estimates on the generalization error of physics-informed neural networks for approximating PDEs. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2022, 42, 2277–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.C.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. Soliton, breather, and rogue wave solutions for solving the nonlinear Schrödinger equation using a deep learning method with physical constraints. Chin. Phys. B 2021, 30, 060202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Chen, Y. Complex dynamics on the one-dimensional quantum droplets via time piecewise PINNs. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2023, 454, 133851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Perdikaris, P. PirateNets: Physics-informed Deep Learning with Residual Adaptive Networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 25, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kashefi, A.; Mukerji, T. Physics-informed PointNet: A deep learning solver for steady-state incompressible flows and thermal fields on multiple sets of irregular geometries. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 468, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudabadbozchelou, M.; Karniadakis, G.E.; Jamali, S. nn-PINNs: Non-Newtonian Physics-Informed Neural Network for complex fluids modeling. Soft Matter 2021, 18, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mengge, D.; Bai, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D. Complex-valued physics-informed machine learning for efficient solving of quintic nonlinear Schrödinger equations. Phys. Rev. Res. 2025, 7, 013164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Yan, M.; Li, X.; Xia, Z. Complex Physics-Informed Neural Network. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohuț, A.I.; Popa, C.A. When Should We Use Complex-Valued PINNs? Case Study on First-Order ODEs. 2025; Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Teh, Y.W., Titterington, M., Eds.; Chia Laguna Resort: Sardinia, Italy, 2010; Volume 9, pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Orr, G.; Müller, K.-R. Efficient BackProp. 2000. Available online: https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/classes/wi08/cse253/Handouts/lecun-98b.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Maciej, S.; Alessandro, T.; Martin, T. Revisiting Initialization of Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.09506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ni, R.; Xu, Z.; Kong, K.; Huang, w.R.; Goldstein, T. GradInit: Learning to Initialize Neural Networks for Stable and Efficient Training. Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 16410–16422. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, B.; Risto, M. AutoInit: Analytic Signal-Preserving Weight Initialization for Neural Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2109.08958. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mohuț, A.-I.; Popa, C.-A. Towards Stable Training of Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Holomorphic Initialization Approach. Mathematics 2026, 14, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14030435

Mohuț A-I, Popa C-A. Towards Stable Training of Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Holomorphic Initialization Approach. Mathematics. 2026; 14(3):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14030435

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohuț, Andrei-Ionuț, and Călin-Adrian Popa. 2026. "Towards Stable Training of Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Holomorphic Initialization Approach" Mathematics 14, no. 3: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14030435

APA StyleMohuț, A.-I., & Popa, C.-A. (2026). Towards Stable Training of Complex-Valued Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Holomorphic Initialization Approach. Mathematics, 14(3), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14030435