1. Introduction

Undoubtedly, video surveillance systems are key components to security infrastructure, with their preventative effects being well documented, e.g., ref. [

1] reports a 25% crime decrease in parking lots and a 10% decrease in town centres. Furthermore, the contribution of video surveillance archives to forensic analysis of security events cannot be understated. Of particular importance to such systems is the ability to quickly identify (and possibly recognize and track) new objects entering the monitored area. This is conducted by analyzing the captured frames, nowadays with the use of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Naturally, as video resolution increases, so does the potential object detection accuracy of the DNN, but also the computational overhead of it. Even more, higher resolutions mean higher bandwidth and storage demands, respectively, for transmission and archiving. Since transmitting and storing raw video data is not a valid option due to immense size, codecs are used.

Research on video coding standards has been avid in the past years. From the Blu-ray era Advanced Video Coding (AVC) [

2] to its successor, High Efficieny Video Coding (HEVC) [

3], and nowadays the 8K era Versatile Video Coding (VVC) [

4], the challenge has always been the same, namely, to provide high compression rate, while incurring minimal quality loss. In order to achieve the aforementioned purpose, the frame is split into blocks of pixels, e.g., macroblocks of 16 × 16 pixels in H.264/AVC, Coding Tree Units (CTUs) of up to 64 × 64 pixels in HEVC and 128 × 128 in VVC. Spatial and temporal redundancies among blocks (or parts of them) are identified and exploited to achieve compression. Unfortunately, this comes at a high computational cost, especially as far as newer standards are concerned, since they employ more sophisticated methods to improve coding efficiency. For instance, as reported by [

5], compared to HEVC, the VVC standard achieves roughly 50% more compression ratio for the same video quality, but at a tenfold increase in processing time.

Harnessing the computational overhead of video coding standards is of paramount importance for video streaming and teleconferencing. However, it becomes even more important in the video surveillance domain, since it interplays with higher video resolutions, object detection accuracy, archive storage space, bandwidth and real time criteria, in order to define system’s performance as a whole. To speed up the process, in the related literature, both parallelization was proposed at various levels in [

6,

7], and decision tree pruning at various coding steps [

8]. Although such techniques are applicable in the context of a video surveillance system with object detection capabilities, the domain offers a distinct potential (compared to simple live streaming) for identifying what information is important within a frame and what is not. Namely, object-related information is highly important, while background scenery less so.

Driven by the above remark, in this paper, we aim to reduce the encoding time and bitrate (thus, needed bandwidth and storage space) of a surveillance stream by avoiding the encoding and transmission of areas unrelated to objects. To do so, we take advantage of the ability provided by new video coding standards to split a frame in a grid-like fashion into tiles. Tiles are rectangular areas comprised of multiple blocks and can be encoded and transmitted separately. Furthermore, we tackle the problem of when to invoke the DNN for object detection, since it plays an important role in system accuracy and processing time overhead. Last but not least, we judiciously use coding parameters to enhance quality where objects appear (or are estimated to appear). Our contributions include the following:

We propose a tile partitioning scheme, with the aim of maximizing the area covered by tiles containing no objects; these tiles are skipped during encoding.

We propose a scheme based on pixel variance to identify whether invocation of object detection module is needed or not.

The CTUs (blocks) of a tile containing one or more objects are encoded with different quality parameters depending on whether they, in turn, contain an object or not; since objects might move, a variance based method is proposed to estimate the CTUs involved with object movement; the method is applicable in the interval between subsequent object detection invocations.

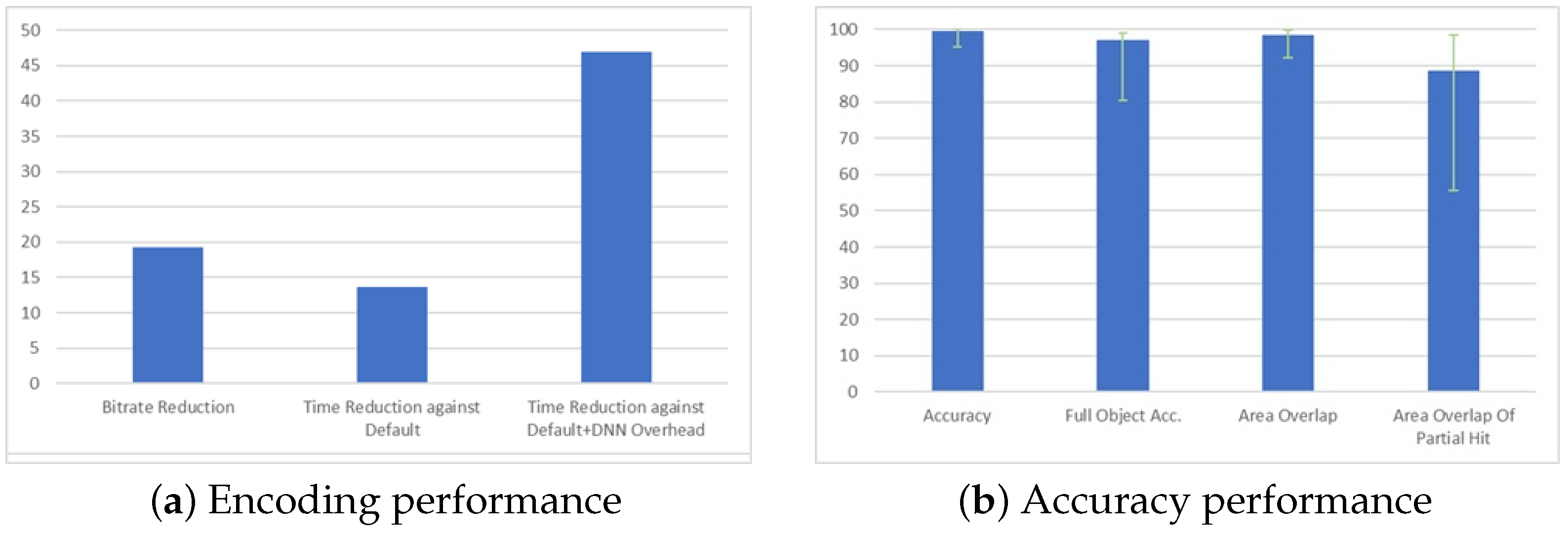

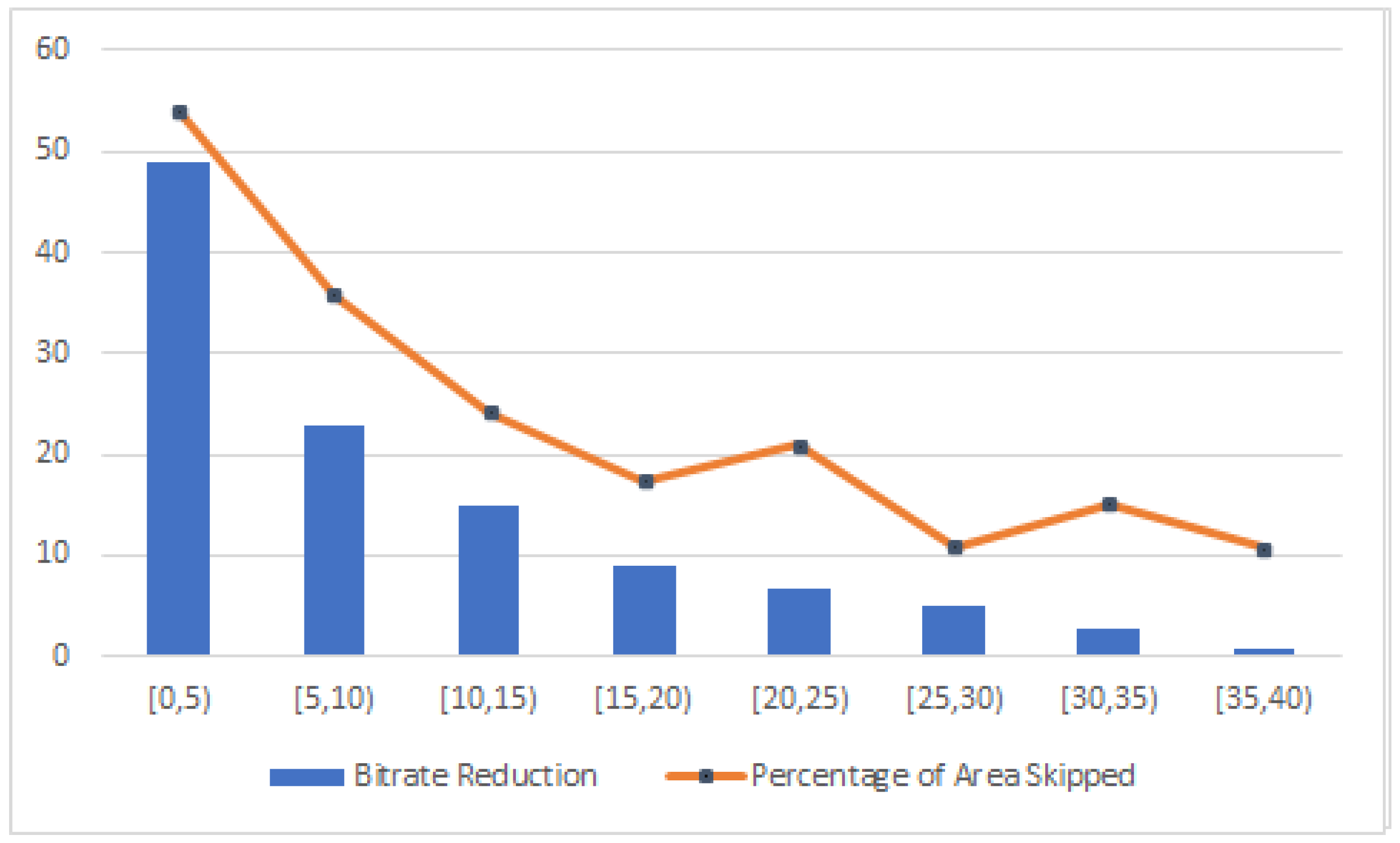

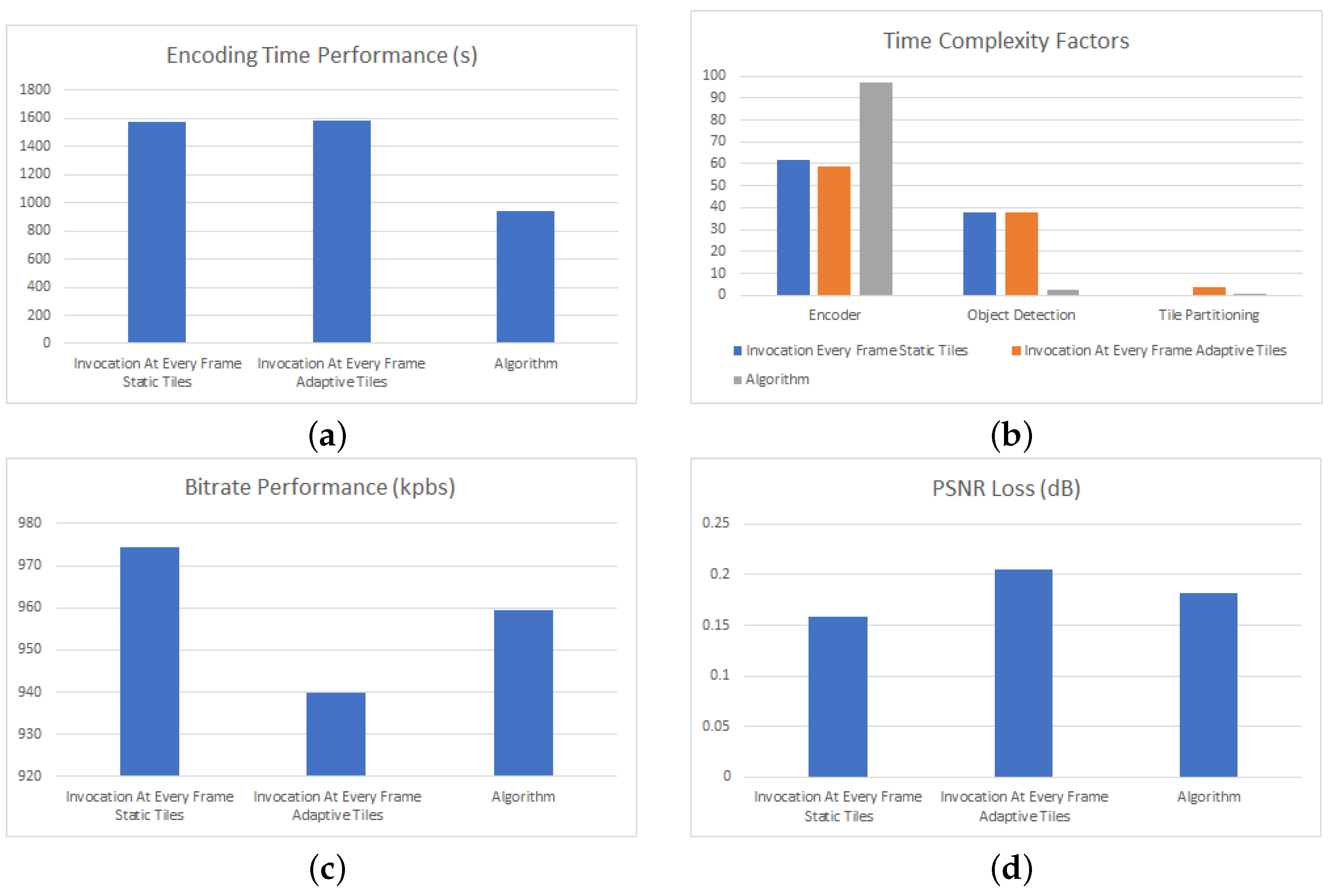

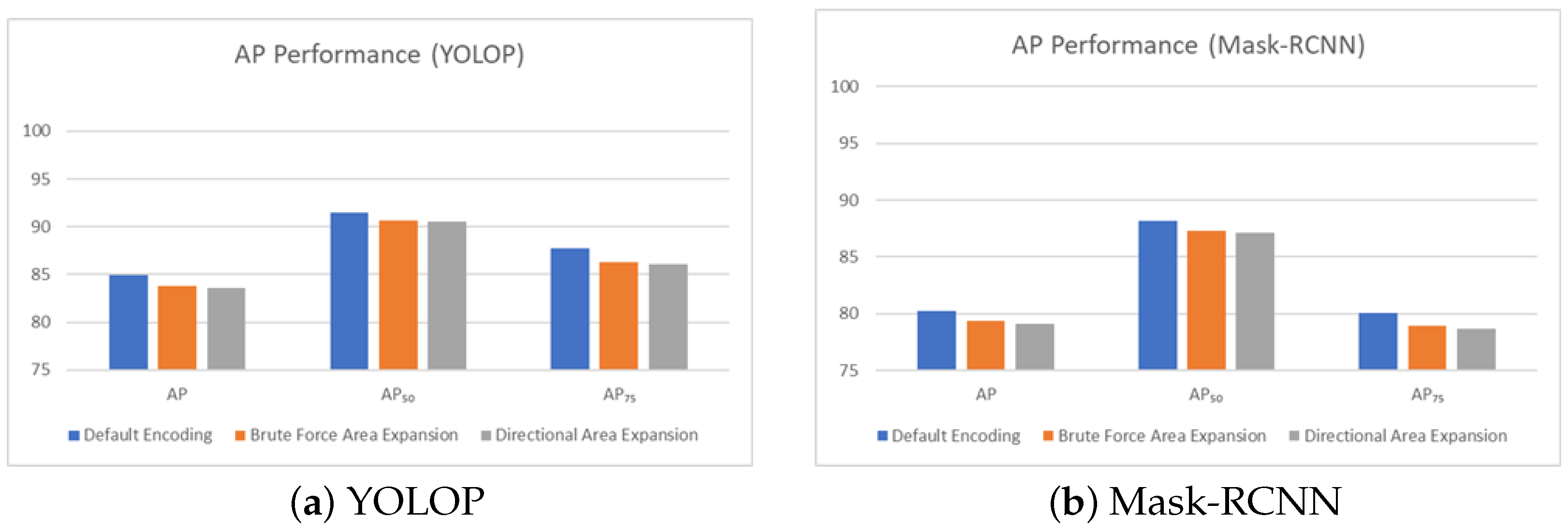

In combination, the above three schemes are able to reduce processing time overhead and bitrate, at only a small loss in object detection accuracy. Namely, using the Versatile Video Encoder (VVEnC) [

9] for the VVC codec, Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (MASK-RCNN) [

10] for object detection, and the University at Albany Detection and Tracking (UA-DETRAC) dataset [

11], an average reduction of more than 13% in processing time and 19% in bitrate were recorded against a default encoding scheme with identical coding parameters, performing no object detection. These results highlight the merits of our approach, especially since the comparison was against a scheme with no object detection overhead. Furthermore, these merits come at a very small loss in accuracy of roughly 1%. Comparison with simpler variations and related work further establishes our algorithm as a valid trade-off between accuracy and other performance metrics. Last but not least, we should note that our methodology is not Deep Neural Network (DNN)-dependent (any object detection module could be incorporated). It is also not video standard-dependent, as long as the standard supports tiles. For instance, it is applicable to both HEVC [

3] and AOMedia Video 1 (AV1) [

12].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of video coding.

Section 3 discusses related work.

Section 4 illustrates the algorithm proposed in this paper, which is experimentally evaluated in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 includes our concluding remarks.

2. Video Coding Overview

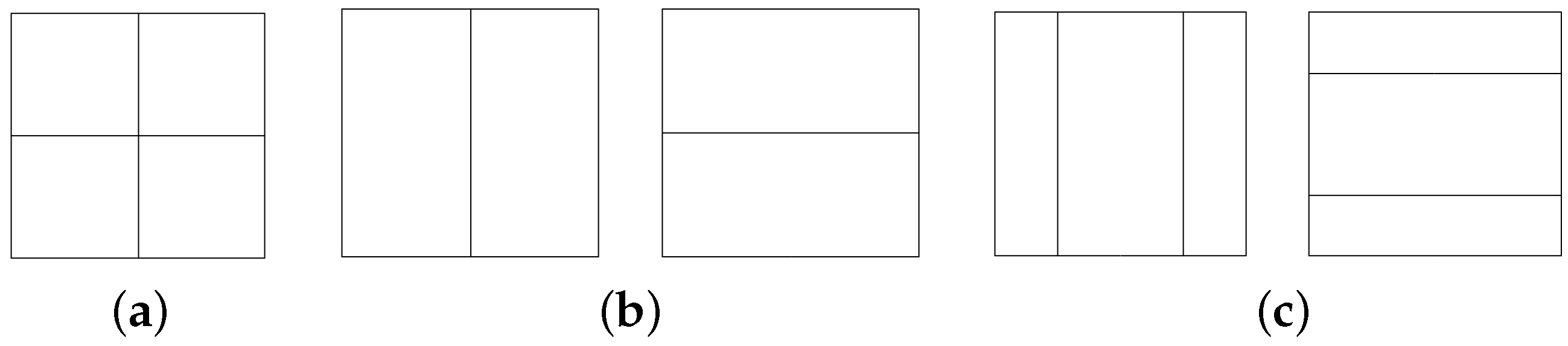

As with most compression methods, video encoding aims to exploit redundancies in data. Video encoding addresses spatial and temporal redundancies through hybrid encoding, obeying a trade-off between quality and compression rate. Firstly, each frame is divided into blocks. In AVC, macroblocks (MBs) were used, whereas in HEVC and VVC, CTUs are employed. The encoder then aims to find data redundancies in each block. The block structure offers content-adaptive capabilities, whereby a block can be further subdivided according to its visual complexity. MBs, whose original size is 16 × 16 pixels, can be divided up to 4 × 4 blocks, while CTUs, which can be up to 128 × 128 in size, can be quad, binary, or tertiary split in Coding Units (CUs). The splits available in VVC are depicted in

Figure 1. CUs can be further split, with the minimum size of sub-blocks reaching 4 × 4.

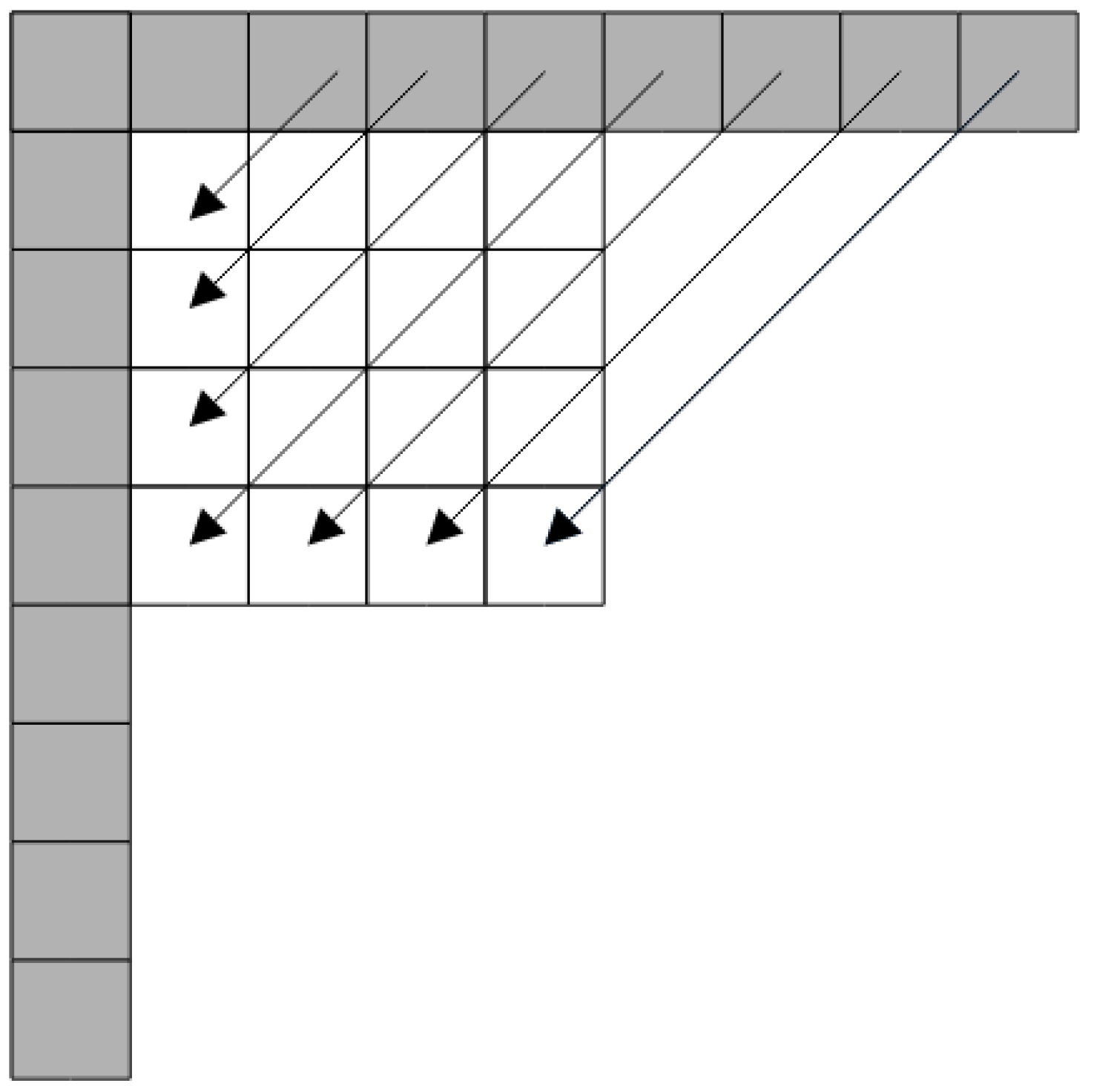

Spatial correlations are exploited through intra-frame encoding. In intra-frame encoding, instead of transmitting the pixel values of the block as is, we can infer the values of the pixels through reference pixels. The pixels from top, top left, and left neighboring blocks are used as reference, specifically the ones bordering the block to be encoded. Extrapolation of the original block from reference pixels is conducted using various methods called intra-prediction modes. For instance, in VVC, there exist 67 such modes. An example of how intra-prediction functions is shown in

Figure 2. In principle, all modes are tested and the one achieving the best trade-off between perceptual loss and compression ratio is selected. Since reference pixels are already encoded in the stream, deriving the predicted block at the decoder side requires only transmitting the selected intra-mode.

Temporal redundancy is present in a video stream due to the fact that among consecutive frames large parts of a scenery remain almost unchanged. Inter-frame coding is employed in order to capitalize on the above. A block in the current frame is inter-predicted from previously encoded reference frames. In order to capture possible motion, a search area (typically consisting of surrounding blocks) is evaluated and the previous location at the reference frame of the block to be encoded is defined. Thus, deriving the prediction block on the decoder side requires only information about the location found, which is typically referred to as the Motion Vector (MV). Temporal redundancy is present throughout a video as the visual content in adjacent frames remains largely the same. In this case, inter-frame coding is employed. A block in the current frame is searched in previously coded frames. If the current block is located in a reference frame, then it can be inferred through the frame it was found in, alongside the corresponding MV.

Regardless of whether intra or inter-prediction is used to form the prediction block, differences between actual and predicted values must be tackled. For this reason, a residual block capturing these differences is calculated and transmitted. The residual block can be transmitted in a lossless or in a lossy manner, depending on the configuration of the compression rate/visual loss trade-off, whereby the error is transformed though Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT). In a lossy compression scenario, the Quantization Parameter (QP) is used by which the error can be quantized. As such, lower QPs yield higher quality at an expense in bitrate, whereas high QPs exhibit the opposite trend. In a hybrid encoding setting, a block can be coded through intra or inter-prediction with the most suitable solution being the one which minimizes cost

J in Equation (

1). Distortion is denoted by

D, bitrate cost is represented with

R, and

is a constant that represents the trade-off between quality and bitrate. All of the encoded information is then subjected to entropy coding to further reduce coding overhead.

High-level partitioning is present in video codecs enabling the selected transmission of parts of the frame together with parallelization, both at the encoder and the decoder side. The high-level structures present in VVC are tiles, slices, and subpictures. Tiles are rectangular areas of CTUs that form a tile grid, whereas slices are groups of CTUs that can be categorized as either rows of contiguous CTUs or rectangular areas. Subpictures are groups of slices offering higher degrees of independency and are mainly used in Virtual Reality (VR) settings. Lastly, frames are organized in Groups of Pictures (GOPs). The GOP structure has a fixed number of frames and typically remains unchanged throughout a video stream. Among others, the GOP structure defines reference dependencies among frames. Frames are characterized depending on the prediction scheme used as I-Frames, P-frames, and B-frames. I-frames are intra-predicted, whereas in P- and B-frames inter-prediction is used based on one or two reference frames, respectively.

3. Related Work

Our work is in the context of intelligent surveillance systems, whereby camera feeds are processed in an automatic manner, in order to identify objects and events of interest. Object detection has received significant research effort in the past varying from methods related to a single image in [

13,

14], up to detecting and tracking moving objects in a video feed in [

15,

16]. Various neural networks have been proposed for the problem, with more recent efforts concentrating on DNNs, e.g., refs. [

10,

17,

18,

19]. Of larger scope is research focusing directly on identifying security events. For instance, in [

20,

21], DNNs are used in order to classify video frames as regular or irregular and subsequently generate security alarm events. Regardless of the scope, common to the aforementioned works is a general processing pattern whereby the frames of a video stream are processed by a neural network and then encoded by some video coding standard. Compared to the aforementioned works, our goal is different, namely, to optimize both processing time and bitrate in surveillance streams with automatic object detection. As such, from the standpoint of this paper, object detection is only a component whose particularities do not limit the applicability of our methodology. For the record, it was decided to incorporate the DNN proposed in [

10], due to its wide use in the field.

In order to achieve the targeted optimizations, our algorithm is based on three main tools, namely, (a) tile partitioning in order to reduce the total encoded area, (b) differentiation of quality levels in CTU encoding depending on whether CTUs contain objects or not, and (c) sparing invocation of the DNN. Strictly speaking, each of the aforementioned tools can be found in the literature in some form.

Content-adaptive high-level frame partitioning in VVC is discussed in [

22,

23]. In [

22], the goal is to identify and group together regions of interest into tiles and subpictures with the aim of improving quality, while [

23] discusses (among others) tile partitioning as a means to parallelize the encoding process. In this paper, tile partitioning is performed with the aim of maximizing the total area that will be skipped in the encoding process, due to the fact that it contains no objects.

As far as CTU coding is concerned, there exist two main research directions that are complementary to our work. The first aims to speed up the process by pruning decisions at tree partitioning level [

24], at intra-mode level [

8], etc. In the paper, we take advantage of the corresponding optimizations implemented by the encoder’s Low Delay Fast setting. The other direction concerns quality and bitrate trade-offs. Refs. [

25,

26] are works advocating saliency-driven encoding whereby low information CTUs are encoded at lower quality. For surveillance videos, ref. [

27] explores spatiotemporal relations between blocks containing background and the ones containing objects, in order to provide better video feedback to object detection algorithms, while in [

28], foreground and stationary background are encoded and stored independently and combined during the decoding phase. Moreover, the authors in [

29] propose a downsampling/Super Resolution method explicitly trained for tasks such as object detection and semantic segmentation. Concerning suitable video configurations in traffic surveillance and dashcam video content, ref. [

30] constructs a surveillance video system that tracks object movement and position while adapting the video coding configuration based both on content and network congestion. Similarly, ref. [

31] proposes a deep reinforcement learning tool that adaptively selects a suitable video configuration, in order to balance the trade-off between bitrate and DNN analytic accuracy.

Finally, ref. [

32] identifies regions of interest of objects in the frame and encodes such regions with a lower QP. This paper also capitalizes on saliency to improve bitrate on low information CTUs.

Summarizing, the works presented in the previous paragraph have a smaller scope compared to this paper, tackling components of the proposed optimization flow. Of interest are works in the context of multiple cameras. Ref. [

33] proposes to encode from one Point Of View (POV) objects appearing in multiple feeds, while [

34] tackles redundancies both for objects and background appearing in multiple POVs. The focus of this paper is different, tackling the optimization of a single feed, not only with regards to bitrate, but also processing time. Nevertheless, the proposed method in this paper is applicable to multiple feed processing and can be combined with the algorithms of [

33,

34] to further improve results.

Judging from motivation, perhaps the closest work to ours is [

35], whereby the aim is to optimize bitrate and processing time. Here too, tile partitioning is used, with only tiles containing objects being encoded and transmitted. Towards this, a bitrate-based algorithm is proposed to estimate the tiles that contain objects. These tiles are afterwards sent to a DNN for object detection. Compared to [

35], our approach differs in many ways. First of all, instead of assuming fixed tile partitioning, we use adaptive tile partitioning based on objects’ appearance. This is crucial, in order to better capture the dynamics of moving objects and enable more optimization opportunities. Secondly, we develop the heuristic to decide whether the DNN should be invoked or not. This heuristic is based on CTU variance calculation, which does not require prior CTU encoding, thus enduring small processing time. In contrast, in [

35], all CTUs are first encoded and then the presence of objects at tiles is estimated based on bitrate. Finally, even within tiles that contain objects, there exist CTUs with background information. Contrary to [

35], we capitalize on this fact to further reduce bitrate. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to use both tile partitioning and salient-based coding, in order to achieve a composite optimization target of improving bitrate and processing time, while maintaining high coding quality in areas containing objects.

4. Algorithm

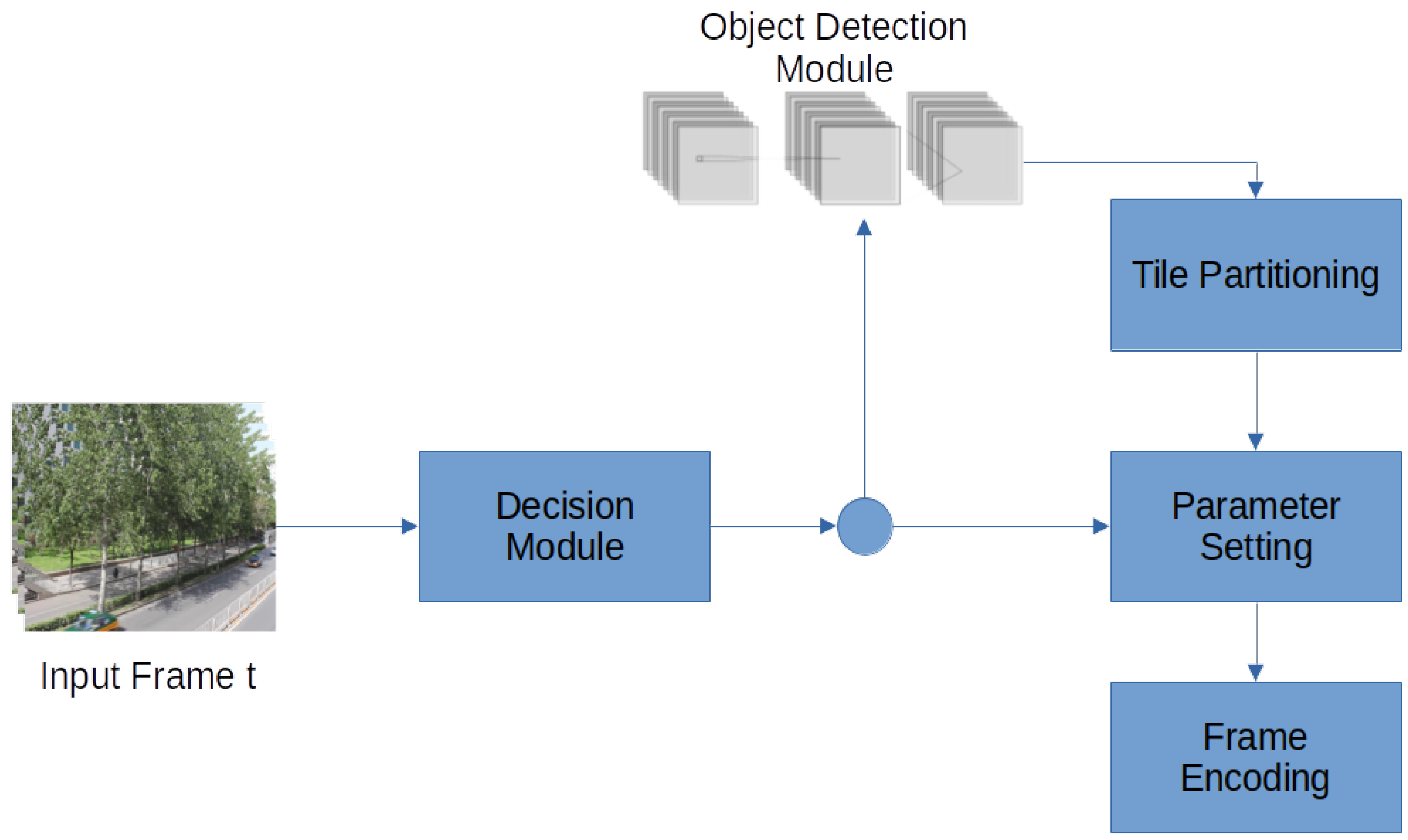

The algorithm proposed in this paper is invoked upon the arrival of each consecutive frame of a surveillance video. The processing involved is organized in a modular fashion, with the input being a raw frame and the final output being the encoded representation of it. The general flow of the algorithm is depicted in

Figure 3. First, a Decision Module is activated, in order to determine whether object detection should be performed or not. In order to harness complexity, a positive decision does not affect the algorithmic flow immediately, but instead takes place at the starting frame of the next GOP. In this case, the object detection module consisting of the DNN presented in [

10] will be invoked and the CTUs containing objects (or parts of them) will be marked. Then, the tile partitioning module will calculate a tile grid so as to minimize the total area of tiles containing marked CTUs. Regardless of whether object detection and tile partitioning are performed or not, the algorithm proceeds with the parameter setting module, which performs two main tasks. Firstly, it sets tiles containing no objects to Skip mode. Then, in the remaining ones, it selects different QP levels for each CTU, depending on whether they are marked or not. Since object detection is not performed on every frame, the detected objects at the beginning of a GOP might move on intermediate frames. For this reason, the parameter setting module uses the same QP level not only for the marked CTUs but also for adjacent ones that are estimated as possible object hosts. Finally, the encoding process takes place.

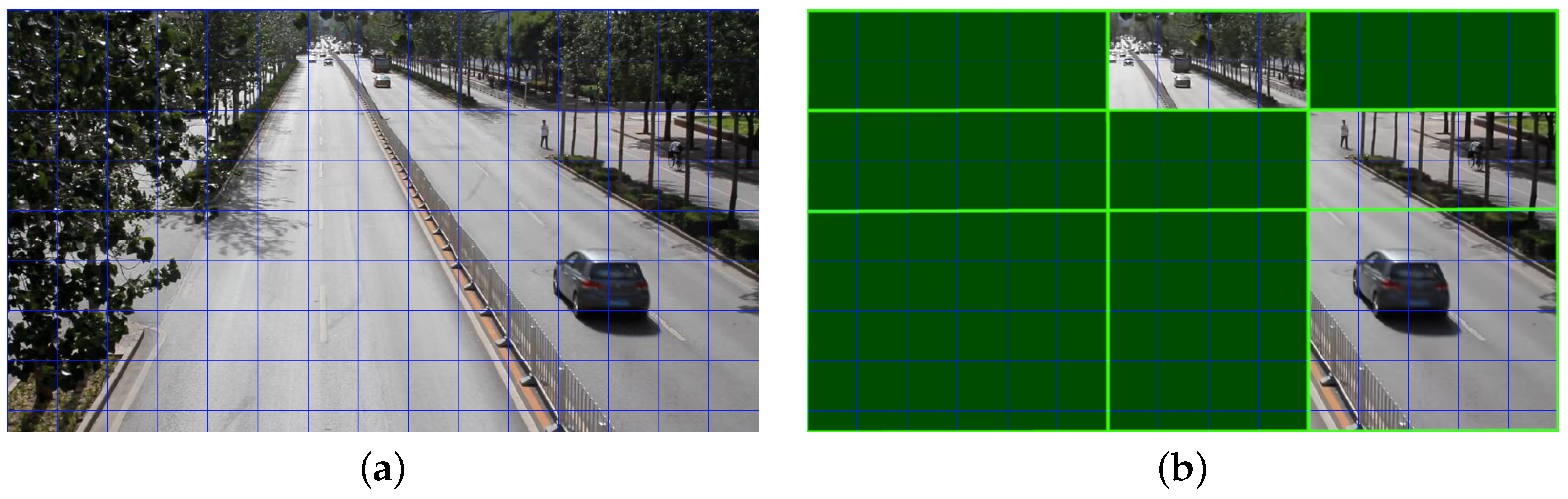

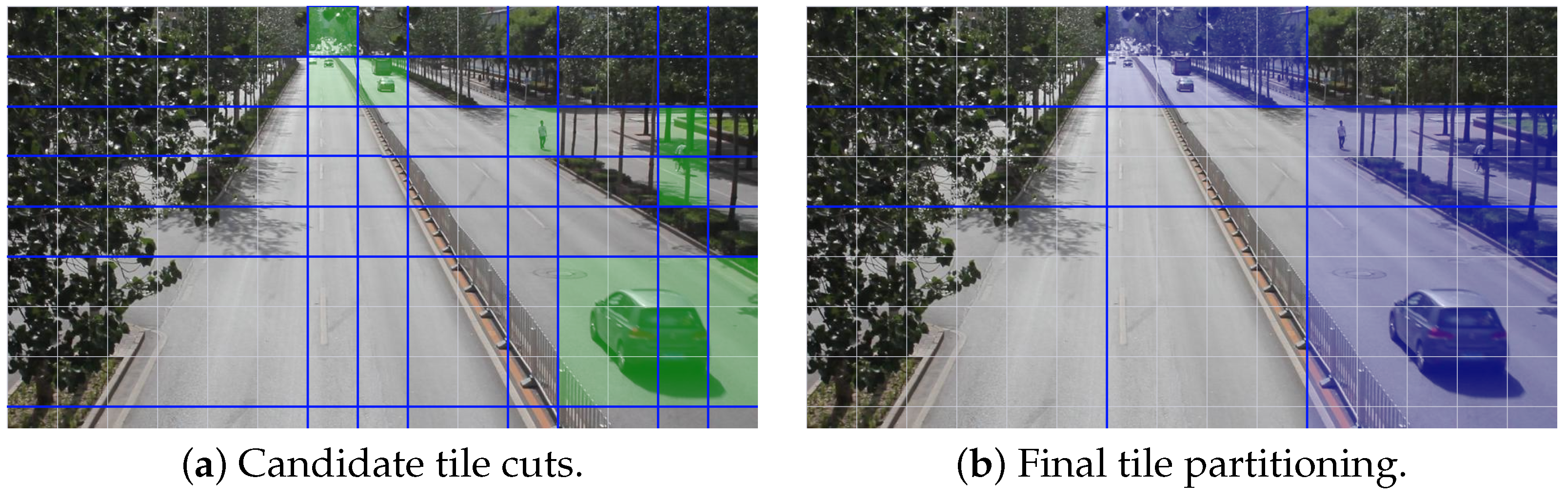

An example run of the algorithm is shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4a shows the input frame and the CTU splitting of it, while

Figure 4b shows which parts will be encoded and which ones will be skipped. As it can be observed (shaded areas), the object detection module recognizes the car in the bottom right, the pedestrian ahead of it, a bicycle rider in the right part, and the cars in the upper part of the frame as objects. It also identifies trees and the shades of them, the guard rail, and the lanes as background. Given the desired dimensions of the tile grid (3 × 3 in the example), the tile partitioning module defines tile boundaries so as to maximize the area of tiles that contain no objects and will be skipped. Following, we describe in detail the algorithmic modules.

4.1. Object Detection Module

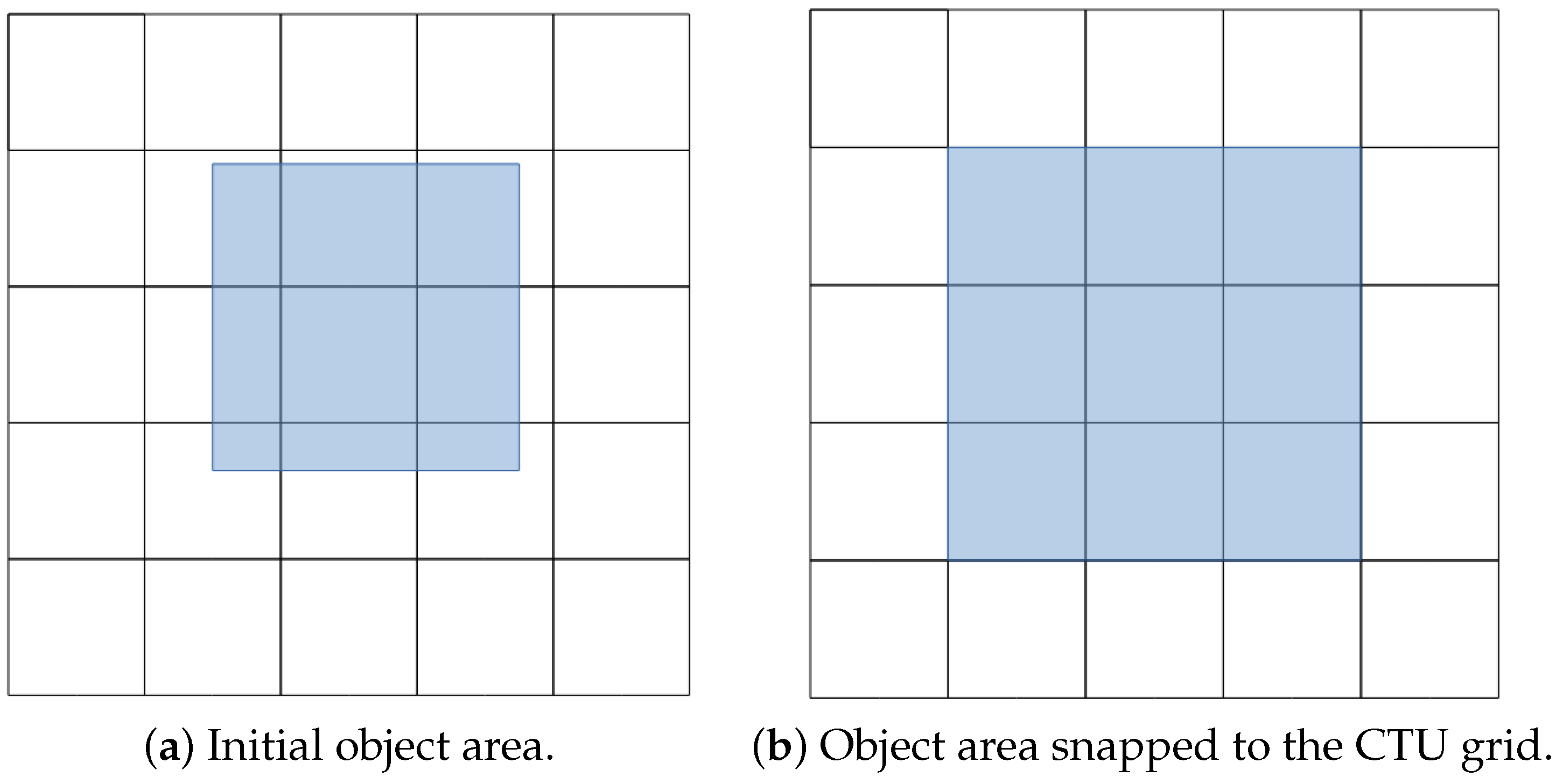

During this process, the frame is sent to the DNN. The DNN’s output consists of a mask as well as a minimum bounding box area for each object present in the image. We solely work with the bounding box areas of the objects. In order to comply with the VVC standard, we snap the rectangular areas of the objects to the CTU grid according to Equation (

2), for an area

a with

a.x1 and

a.x2 horizontal boundaries and

a.y1 and

a.y2 vertical boundaries in pixels, with

size being the width/height of a CTU in pixels, forming the

Snap function.

This way, we expand the area for an object derived from the DNN to contain CTUs that fully or partially overlap with said object. The snapped area coordinates are measured in CTUs. With this process, we essentially mark which CTUs in the frame contain objects.

Figure 5 exhibits how this process functions. The marked CTUs in the form of

coordinates along with the areas containing objects are then sent to the encoder by which the Tile Partitioning and the Parameter Setting Modules operate.

4.2. Decision Module

Object detection comes at a computational cost. Therefore, a per frame invocation strategy, although being the most adaptive in scene changes, might result in excessive processing delays. Moreover, many of these invocations might be redundant, since a total change of scene and object involvement on every frame is rather a seldom event. In this subsection, we describe the Decision Module which is responsible for defining whether object detection and subsequent optimizations (tile partitioning, etc.) should take place or not.

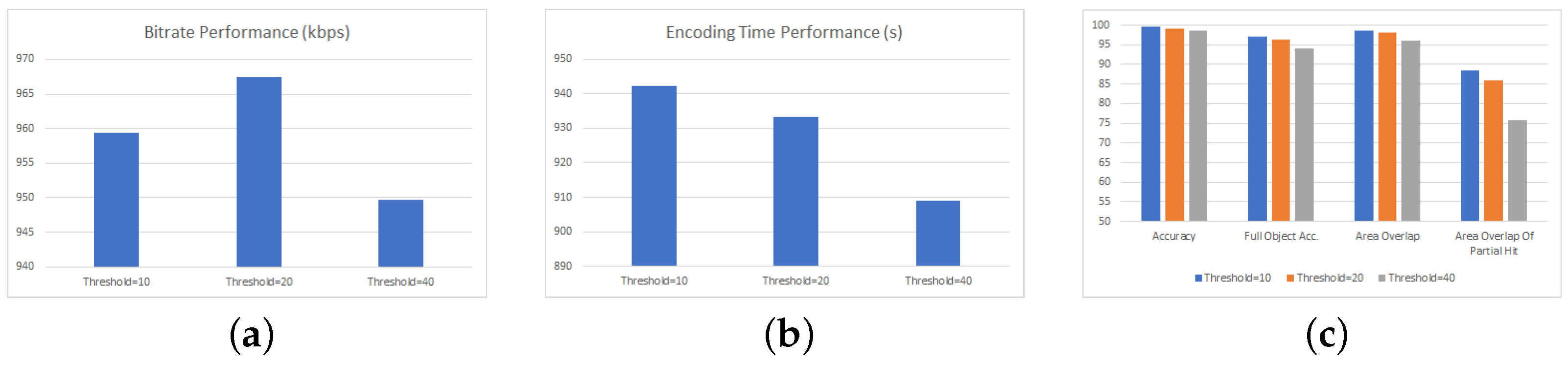

For the starting frame of the first GOP in the video sequence, object detection is invoked and subsequently tile partitioning occurs, whereby two tile categories are defined as follows: those which contain objects and those which do not. Regardless of the tile type, in the first frame, all tiles are encoded and transmitted; nevertheless, in subsequent frames, tiles with no objects are skipped. It is possible that at some point, a new object enters such a tile. To capture the case, for each CTU belonging to skipped tiles, the Decision Module computes the luma variance of its pixels in the current and the previous frame and calculates their absolute difference. If the absolute difference exceeds a threshold, it denotes the possible existence of a new coming object. Instead of performing object detection and tile adaptation instantly, we delay their invocation until the first frame of the subsequent GOP. In this way, tile structure remains constant within a GOP, which aids coding efficiency, while DNN invocations are limited to at most one per GOP. Undoubtedly, this is a trade-off that comes at the cost of reduced bitrate savings, which, as shown in the experiments, is minimal. As it pertains to the variance threshold, this is a tunable parameter. Its value should be small enough so as not to miss object movement and large enough to avoid being triggered by minor effects, such as rain, slight movements of camera, etc.

4.3. Tile Partitioning Module

Given the desired dimensions of the tile grid,

M × N, and the output of the object detection module, which contains the rectangular areas of objects found within the frame, the tile partitioning module aims at defining the exact

M − 1 horizontal and

N− 1 vertical cuts that result in forming tiles so as to maximize the frame area that can be skipped during encoding. Specifically, the module takes as input all object boundaries, snapped to CTUs’ edges, together with the information for each CTU as to whether it contains an object or not. These boundaries form a tentative set of horizontal and vertical cuts, denoted by

cutH and

cutV, respectively. Encoders place restrictions on the minimum allowable tile size. For instance, in HEVC, a tile should consist of at least one row of two CTUs. Since it is recognized that extremely small tiles have an adverse effect on quality [

36], but also in order to reduce complexity, we enforce a minimum tile size of 2 × 2 CTUs. This entails that all the selected cuts, either horizontal or vertical, should have a distance of at least two CTUs from each other. It also means that horizontal or vertical cuts just after the first row or column, respectively, are ineligible.

The two sets of tentative vertical and horizontal cuts (

CutV and

CutH) that were produced with the above methodology must be of size

M and

N, respectively. In case that the available eligible horizontal and vertical cuts are less than

M − 1 or

N− 1, respectively, we introduce eligible cuts to supplement the difference, according to the

populateSet function shown in Algorithm 1. The function operates for both horizontal and vertical cuts. In the case of horizontal cuts, the algorithm takes as arguments

set =

CutH,

bound =

N, and

sizeInCtu as the height of the frame in CTUs, whereas in the case of columns, the arguments are defined as

set =

CutV,

bound =

M, and

sizeInCtu being the width of the frame in CTUs.

populateSet works in iterations, each time adding one cut in a greedy manner, with the optimization criterion being the balancing of the distances between cuts.

| Algorithm 1 PopulateSet(set,bound,sizeInCtu) |

- 1:

while

do - 2:

- 3:

for in do - 4:

- 5:

if then - 6:

continue - 7:

end if - 8:

- 9:

- 10:

if then - 11:

continue - 12:

end if - 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

if then - 17:

- 18:

- 19:

end if - 20:

end for - 21:

- 22:

end while

|

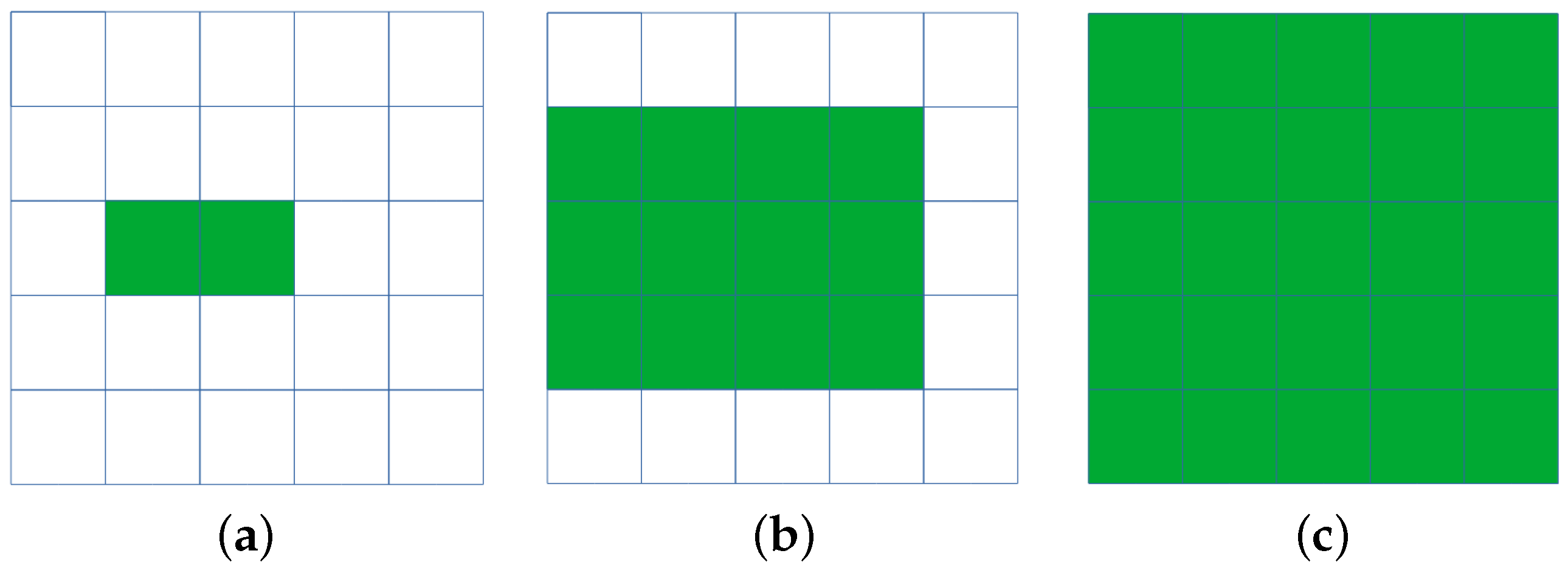

After the populateSet process, we construct the possible M-1 and N-1 enumerations of CutH and cutV, which are stored into tileRowCombinations and tileColCombinations sets, respectively. Clearly, the candidate tile grids for consideration are the ones given by the Cartesian product of the two sets, |tileRowCombinations| × |tileColCombinations|. The enumeration process is a brute force approach that theoretically leads to intractable computations as M and N approach infinity. However, in practical cases, surveillance frames have limited boundaries and the computation is not only tractable, but also quite fast as discussed in the experiments.

Each candidate tile grid is evaluated with respect to the frame area that can be skipped during encoding. Specifically, the tiles containing no objects are identified and the number of the CTUs they contain acts as the optimization criterion (see Equation (

3)), forming a Benefit function (denoted as

B) that should be maximized.

Surface is a function of a given tile

t that calculates the area of said tile in CTUs, while

NumOfObjects is a function of a tile

t that calculates the number of objects being contained within said tile. In essence, the Benefit function calculates the areas of all tiles that contain no objects.

The tile grid with the highest score is selected for implementation. Algorithm 2 illustrates the whole tile partitioning process in pseudocode. First,

cutV and

cutH are populated using object boundaries. This is conducted iteratively (lines 3–8), on the output of the Object Detection Module,

dnn_areas. Then, the

populateSet function is called to add candidates cuts if needed (lines 9–10). Afterwards, row and tile combinations are calculated in lines 9–14. The final tile-grid selection process takes place in lines 16–25, whereby the benefit of all possible tile-grid configurations is calculated and the configuration with the maximum benefit (

maxBenefit) is selected. The output of our algorithm is stored in

bestTileConfig, which contains the optimal tile grid. An example invocation of this process is shown in

Figure 6.

| Algorithm 2 TilePartitioning |

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

for i in do - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

end for - 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

for in do - 17:

for in do - 18:

- 19:

// as per Equation ( 3) - 20:

if then - 21:

- 22:

- 23:

end if - 24:

end for - 25:

end for

|

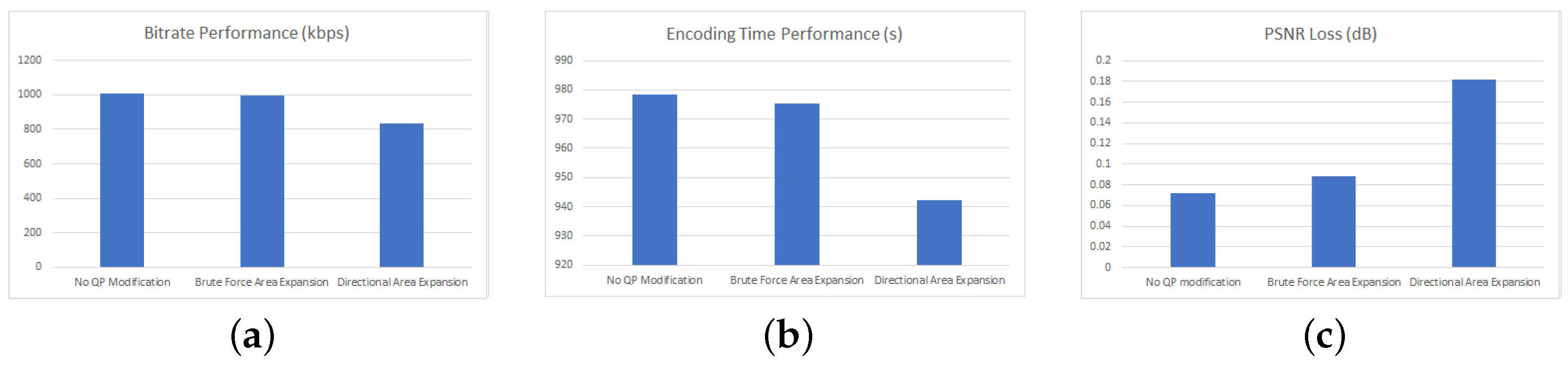

4.4. Parameter Setting Module

This is the last step before frame encoding. Firstly, encoding parameters change to define, if necessary, a newly computed tile partitioning. With the exception of the first frame of the starting GOP of the sequence, tiles with no objects are skipped and can be inferred from previously encoded frames, while the rest are encoded with the selected parameters of the encoder. The encoding mode and parameters used in the paper are described in the experiments.

In order to further optimize encoding time and compression ratio, we further optimize encoding parameters of CTUs resting in non-skipped tiles. We use pertinence-based encoding, whereby a pertinent CTU is one containing whole or part of an object. The process works with two quality levels, high and medium, whereby pertinent CTUs are encoded at high quality and the rest at medium. We select quality levels to directly relate to two distinct values of the quantization parameter QP, namely, the default of the encoding mode corresponds to high and an increased value of it, to the medium level. Obviously, the two QP levels are tunable parameters.

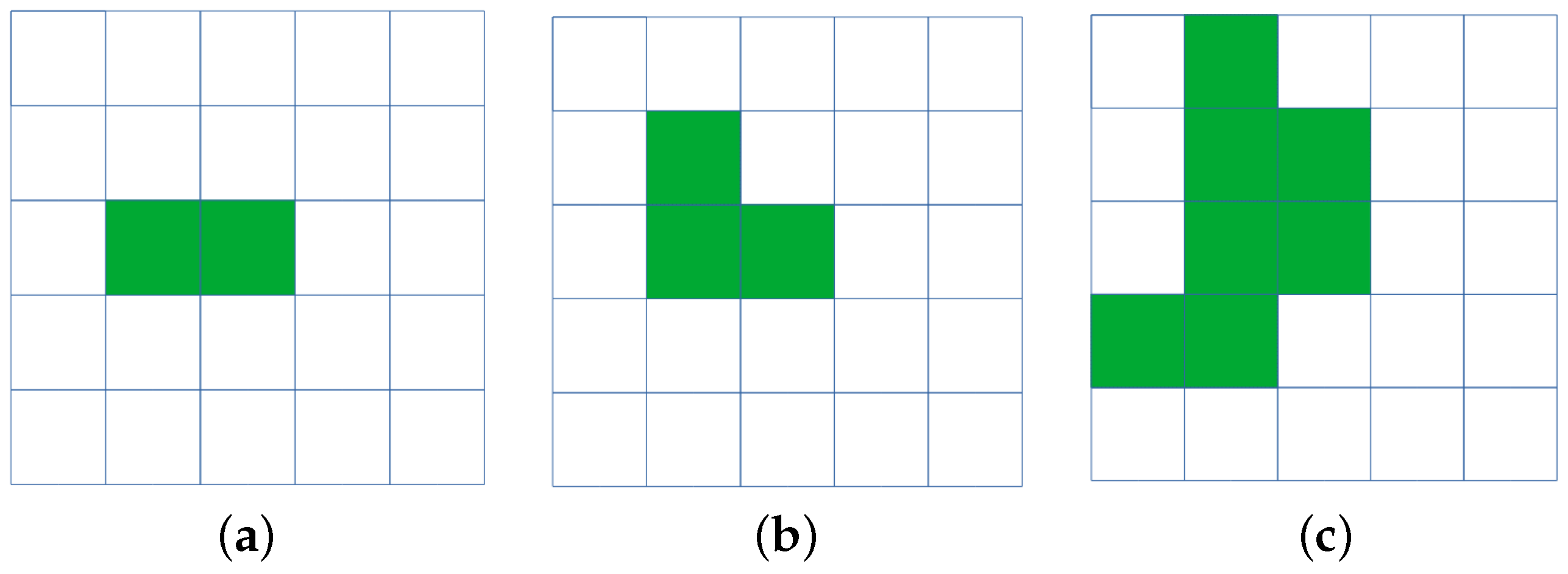

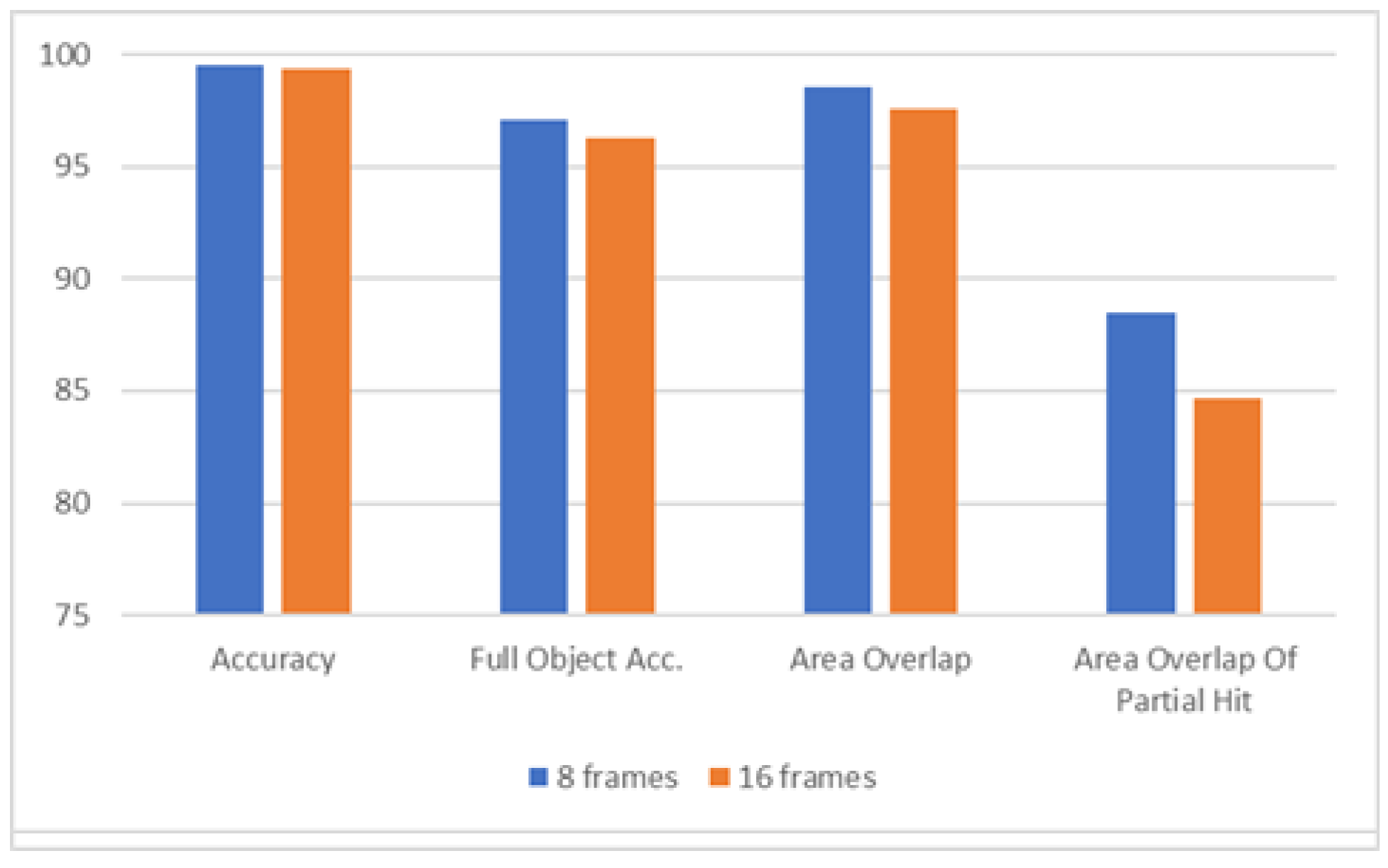

Pertinent and non-pertinent CTUs are defined at the frame where object detection is performed. Afterwards, the object in a pertinent CTU might move to neighboring CTUs. The case where it moves to the CTU of a skipped tile is captured in the Decision Module through variance detection. Nevertheless, a mechanism is needed to tackle the case whereby it moves on a neighboring CTU belonging to a non-skipped tile. We experiment with two approaches, namely, brute force area expansion and directional expansion. For each pertinent CTU, both approaches define a pertinent area. Initially, this area consists only of the aforementioned CTU. Every × frames (in the experiments it is equal to 2), the area is expanded by adding more CTUs. CTUs are only Eligible for addition if they belong to non-skipped tiles.

In the brute force approach, the expansion consists of adding all adjacent to the pertinent area CTUs, see

Figure 7 for an example. In the directional approach, adjacent CTUs are added according to the variance technique used in the Decision Module. Namely, luma variance of the candidate CTU is calculated for the current and the previous frame and their absolute difference is checked against a threshold. The same threshold value used in the Decision Module is used here too.

Figure 8 provides an example of the directional method. Notice that in all cases, the pertinent area can only be expanded, or remain the same, meaning that once a CTU is marked as pertinent, it remains so until the next object detection invocation. This is a rather conservative decision, aiming at minimizing potentially negative impacts on quality.