1. Introduction

As the backbone of modern transportation systems, the safe and stable operation of high-speed railways critically depends on the integrity and reliability of track circuits. In contemporary train control architectures, stable track circuit signals serve as a fundamental sensing basis for train detection, route management, and safety decision-making. Recent studies have shown that the functional safety and performance of advanced and autonomous train control systems are highly sensitive to the reliability of underlying detection signals, and signal abnormalities may propagate into system-level safety risks [

1,

2].

Compensation capacitors, as key components of jointless track circuits (JTCs), play an indispensable role in counteracting rail inductance and maintaining signal amplitude and transmission stability, thereby ensuring correct train detection. In practical railway operations, compensation capacitors are continuously exposed to harsh and variable environments, including temperature fluctuations, mechanical vibrations, ballast impedance variations, and electromagnetic interference. As a result, performance degradation or partial failure of compensation capacitors is unavoidable over long-term service.

Once degradation or failure occurs, compensation capacitors may cause induced voltage attenuation, waveform distortion, code loss, and even false occupancy detection, which directly undermine track circuit reliability and increase maintenance workload and safety risks under real operating conditions [

3,

4]. Moreover, these abnormal signal behaviors often manifest differently across operating scenarios such as roadbeds, tunnels, and bridges, where environmental disturbances further amplify signal instability. This multi-scenario variability highlights that compensation capacitor diagnosis is inherently a disturbance-driven problem rather than a purely classification-driven one, thereby placing higher demands on the robustness of signal feature modeling and fault recognition.

At present, the monitoring of compensation capacitor status primarily relies on three approaches: (i) manual inspection, which, although intuitive, suffers from low efficiency, long inspection cycles, and heavy dependence on human expertise, making it unsuitable for real-time requirements in high-speed railway systems [

5,

6]; (ii) track voltage waveform analysis, which infers capacitor status from the received waveform but is highly susceptible to electromagnetic interference and structural reflections, thus limiting recognition reliability [

7,

8]; and (iii) automated inspection using detection vehicles, which enables batch acquisition of signal data but entails high deployment costs and insufficient timeliness [

9,

10]. These approaches primarily depend on empirical judgment or direct waveform characteristics, and their effectiveness degrades significantly under complex and dynamically changing environments.

To overcome the limitations of traditional methods in terms of accuracy, generalizability, and adaptability, intelligent signal processing and learning-based diagnostic techniques have become active research focuses in recent years. On the one hand, sliding-window and adaptive segmentation algorithms have been introduced to capture dynamic local variations in non-stationary signals [

11,

12]. On the other hand, deep learning and transfer learning approaches—such as LSTM, CNN, and Bi-GRU—have shown strong potential for compensation capacitor condition recognition [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Building on these advances, some studies have incorporated attention mechanisms and graph neural networks (GNNs) to enhance structural modeling capabilities [

17,

18], while others have explored generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) to improve adaptability in small-sample and cross-domain scenarios [

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, heterogeneous transfer learning methods have been applied to track circuit fault prediction, effectively mitigating cross-domain distribution discrepancies and improving diagnostic generalization [

22]. Overall, these studies demonstrate the effectiveness of data-driven models in enhancing recognition accuracy, but they largely emphasize model architecture optimization rather than the intrinsic robustness of signal features.

Despite these advancements, most existing studies primarily emphasize model architecture optimization and classification accuracy, while treating signal features as static inputs, with limited consideration of their stability and robustness under environmental disturbances. In real-world railway environments, compensation capacitor signals (CCS) are subject to multiple overlapping disturbances, including bridge structural resonance, ballast impedance fluctuations, and tunnel electromagnetic reflections [

23]. These disturbances induce strong nonlinear distortions—manifested as peak fluctuations, spectral diffusion, and phase drift—that reshape the temporal and spectral distributions of CCS signals. As a consequence, features selected solely based on discriminability may become unstable, poorly separable, and physically uninterpretable across operating conditions, thereby undermining the reliability and generalization of downstream recognition models [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Recent research in feature selection theory further emphasizes that the stability and robustness of feature evaluation metrics are crucial for dependable performance under noisy or perturbed conditions [

28,

29,

30]. Classical optimization strategies such as sparse regularization (LASSO) and Bayesian feature selection can improve accuracy but often lack explicit robustness constraints, leading to unstable feature subsets when the input distribution shifts [

31,

32]. Additionally, equal-weighted feature aggregation schemes have been shown to oversimplify multi-criteria interactions, resulting in diminished discriminability under variable environments [

33]. These limitations reveal a fundamental gap in existing approaches: the absence of a unified framework that explicitly models feature robustness, environmental sensitivity, and structural separability in a cooperative manner.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation (DRFD) framework. Unlike conventional feature selection methods that focus on accuracy-driven ranking, DRFD explicitly treats environmental disturbance as a first-class modeling factor, and evaluates candidate features from three complementary perspectives: statistical significance, environmental stability, and structural separability. The framework operates in two stages: first, a multi-perspective robustness validation mechanism is constructed to quantify feature reliability under cross-condition disturbances; second, a DRFD optimization algorithm integrates these criteria into a unified objective function with adaptive Bayesian weighting and dynamic robustness thresholding, enabling automated and disturbance-aware feature subset selection. Furthermore, real-world CCS data collected under roadbed, tunnel, and bridge conditions are employed to validate the framework through clustering analysis, time–frequency characterization, and multi-condition comparative experiments.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (i)

A unified disturbance-robust feature modeling framework, DRFD, is proposed, which for the first time reformulates statistical significance, environmental stability, and structural separability into a cooperative and optimizable objective function for track circuit signal analysis.

- (ii)

A disturbance–response modeling mechanism is established to quantitatively describe how operating-condition disturbances (e.g., bridge resonance, tunnel reflections, ballast impedance variations) reshape induced voltage responses and feature distributions, thereby bridging physical perturbations and statistical feature behavior.

- (iii)

Comprehensive validation using real-world inspection data collected under roadbed, tunnel, and bridge conditions demonstrates that the automatically distilled feature set (RMS, PF, and CF) achieves superior recognition accuracy, robustness, and cross-condition stability compared with conventional feature selection baselines.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the disturbance-aware modeling of compensation capacitor signals and formulates the robustness-oriented feature evaluation problem.

Section 3 details the DRFD framework, including three-perspective robustness validation and optimization-based feature distillation with theoretical guarantees.

Section 4 reports extensive experimental results on real-world railway data, including robustness analysis, comparative evaluation, and physical interpretation.

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses limitations and future work.

3. Methodology

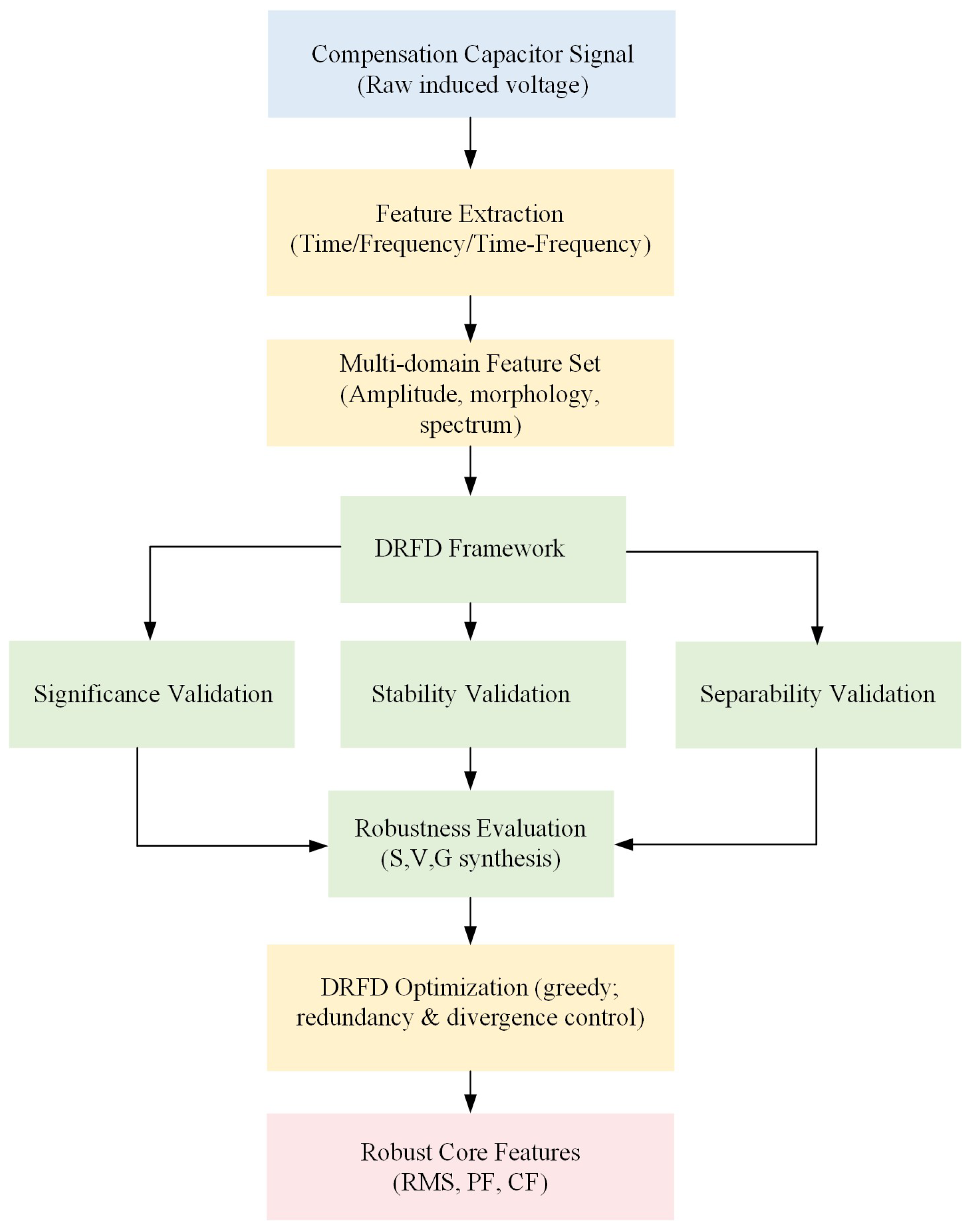

3.1. Multi-Domain Feature Construction and Operator Mapping

Considering the influence of varying structural environments, this study proposes a unified Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation (DRFD) framework. The framework integrates two interconnected components: (i) CCS-TRV (Compensation-Capacitor-Signal Three-Perspective Robustness Validation), which defines robustness criteria that valid features must satisfy from three complementary perspectives—statistical significance, environmental stability, and geometric separability; and (ii) DRFD-based optimization, which reformulates these criteria into an optimizable robustness objective, enabling automated and iterative selection of an optimal feature subset.

Each feature is formulated as an operator acting on the segmented signal, yielding an

N ×

M feature matrix

X, where each element corresponds to the response of the

j-th feature operator applied to the

i-th signal segment. For each feature

, the preliminary robustness score is obtained by combining significance, stability, and separability:

To minimize redundancy and ensure distributional robustness, the DRFD algorithm introduces a subset-level optimization objective:

- (a)

, : Regularization parameters;

- (b)

: Quantification of inter-feature redundancy for subset A;

- (c)

: Quantification of cross-condition distributional divergence for subset A.

Where

A ⊆

F denotes the selected feature subset,

R(

A) quantifies inter-feature redundancy, and

D(

A) penalizes cross-condition distributional divergence to enforce robustness under environmental variations. The final goal is:

- (a)

: Selected feature subset that maximizes the robustness score;

- (b)

K: A constant.

By unifying descriptive robustness evaluation with an optimization-driven selection mechanism, the DRFD framework establishes a coherent bridge between theory and implementation. The distilled feature set integrates multi-domain representations—time, frequency, and time–frequency—thereby preserving amplitude response, morphological detail, and spectral composition under diverse environmental disturbances.

This architecture forms a closed-loop process that links signal acquisition, multi-domain feature validation, and optimization-based feature distillation.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall architecture of the DRFD framework, which integrates signal input, feature extraction, three-perspective robustness validation, and DRFD optimization.

To visualize the complete workflow, the DRFD system starts with the acquisition of raw compensation-capacitor signals, followed by multi-domain feature extraction in the time, frequency, and time–frequency domains. The extracted features are subsequently evaluated through the Three-Perspective Robustness Validation (CCS-TRV) process, which assesses each feature’s statistical significance, environmental stability, and geometric separability.

These validation results are then integrated into the DRFD algorithm, which formulates an optimizable robustness objective and automatically selects the most reliable feature subset. The final output includes the robust core features, ensuring discriminability, stability, and reliability of signal representations across diverse operating environments such as roadbeds, bridges, and tunnels.

3.2. Three-Perspective Robustness Validation

The CCS-TRV module constitutes the first layer of the DRFD framework and provides a theoretical foundation for quantifying feature robustness. It evaluates each candidate feature from three complementary perspectives—statistical significance, intra-condition stability, and geometric separability—ensuring that the selected features remain both discriminative and stable under complex environmental disturbances. This section formalizes the mathematical metrics used for each perspective and establishes their connections to the unified robustness formulation.

3.2.1. Statistical Significance Test

To assess discriminability across operating conditions, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) test is employed to determine whether each feature exhibits statistically significant differences under multiple conditions, given that feature distributions may deviate from normality [

34]. The null hypothesis of identical distributions across conditions is rejected when the K–W statistic exceeds the critical value at significance level

α. Dunn’s multiple comparison test is applied as a post-hoc analysis following the Kruskal–Wallis test to identify pairwise differences under non-normal distributions [

35]. The familywise error rate is controlled using Bonferroni correction [

36]. The significance score

Sj is defined as the average absolute Dunn statistic across all condition pairs, reflecting the overall discriminative strength of feature

j.

3.2.2. Intra-Condition Stability Metric

Dispersion-based stability metrics, such as the coefficient of variation, have been widely adopted to quantify feature sensitivity under environmental perturbations. To evaluate this property, the Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) is introduced as a quantitative stability measure [

37]. For the

j-th feature under condition

c, the ESI is defined as:

where

and

denote the sample mean and standard deviation, respectively, and

is a small regularization term to prevent division by zero. The global stability score

Vj is obtained by averaging the ESI values across all operating conditions.

3.2.3. Geometric Separability Metric

Even if features demonstrate significance and stability, their spatial separability in the feature space must also be verified to ensure effective class distinction. Laplacian Eigenmaps is a classical manifold learning technique that preserves local neighborhood structure and has been widely used for nonlinear feature embedding and separability analysis. Following the standard formulation of Laplacian Eigenmaps [

38], given feature vectors

, the similarity between samples

i and

j is defined as:

where

denotes the k-nearest neighbors of sample

i. Let

and

be the degree and Laplacian matrices, respectively. The low-dimensional embedding is obtained by solving the standard generalized eigenvalue problem of Laplacian Eigenmaps [

38]. Based on this embedding, feature separability is quantified by the ratio between inter-condition distance and intra-condition variance:

A higher (or lower DBI) implies stronger geometric discrimination among conditions. The three metrics— (significance), (stability), and (separability)—collectively define a multi-perspective robustness space for each feature. Their normalized scores are subsequently fused into a unified robustness indicator , which quantifies the discriminative and stable nature of each feature.

3.2.4. Quantitative Formulations for Validation Metrics

To ensure reproducibility, this section presents the quantitative definitions of the three robustness metrics—statistical significance, intra-condition stability, and geometric separability.

- (a)

Statistical Significance via Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s Tests

Each candidate feature was evaluated using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) test to assess whether its distribution differs significantly across different operating conditions. A smaller p-value indicates stronger statistical evidence that the feature exhibits distinct behavior under roadbed, tunnel, and bridge environments. For features that pass the global significance test, pairwise comparisons were further conducted using Dunn’s post-hoc test. To control the familywise error rate arising from multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied, and the corresponding adjusted significance threshold was determined accordingly. A feature is regarded as statistically significant if its associated p-value satisfies the adjusted significance criterion.

- (b)

Intra-Condition Consistency via Environmental Stability Index (ESI)

After inter-condition analysis, the ESI quantifies the consistency of each feature within a single operating environment. While the inter-condition significance test quantified how feature distributions differ across operating environments, the intra-condition stability evaluation focuses on how consistently each feature behaves under a fixed condition. To characterize feature stability under repeated measurements within the same operating condition, dispersion-based statistics were employed. Specifically, the coefficient of variation was used to quantify intra-condition variability, where lower dispersion indicates stronger stability and repeatability. For each feature, stability scores were first computed independently under roadbed, tunnel, and bridge environments, and then aggregated to obtain an overall stability measure across operating conditions. To ensure comparability across features, the aggregated dispersion values were further normalized into a bounded stability score within [0, 1], where higher values correspond to stronger consistency and robustness against environmental perturbations.

- (c)

Geometric Separability via Bhattacharyya Distance and Fisher Discriminant Ratio

To evaluate the geometric separability of features across operating conditions, classical distribution-based and scatter-based criteria were adopted. Specifically, the Bhattacharyya distance was used to quantify the degree of distributional overlap between feature responses under different operating environments, where a larger distance indicates stronger class separation. In addition, the Fisher discriminant ratio was employed to assess the balance between inter-condition divergence and intra-condition dispersion. Higher Fisher ratios correspond to more compact feature distributions within the same condition and greater separation between different operating conditions, thereby reflecting stronger discriminative efficiency. These separability measures complement the statistical significance and stability evaluations, collectively forming the multi-perspective robustness validation framework used in the experimental analysis.

3.3. Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation

The DRFD algorithm constitutes the second layer of the DRFD framework. While CCS-TRV provides a descriptive evaluation of individual features, DRFD transforms these heterogeneous robustness metrics into an optimizable objective function, enabling the automatic selection of the most robust feature subset. This section presents the definition of the composite robustness score, the formulation of the subset-level optimization objective, and the greedy optimization algorithm with theoretical justification.

3.3.1. Single-Feature Robustness Score

Based on the three-perspective validation results introduced in

Section 3.2, each feature is assigned a unified robustness score defined as:

where

denotes the statistical significance score reflecting inter-condition discriminability,

represents the environmental sensitivity index characterizing intra-condition stability,

denotes the geometric separability score in the embedded feature space, and

are weighting coefficients satisfying

. The coefficients

can be empirically tuned or determined through Bayesian optimization to balance discriminability and stability according to specific recognition objectives. Features with higher

are preliminarily regarded as more robust candidates.

3.3.2. Subset-Level Optimization Objective

Although

quantifies single-feature robustness, the final goal of DRFD is to identify an optimal subset of features that maximizes collective robustness while minimizing redundancy and distributional divergence. Accordingly, the subset-level objective function is defined as:

where

is the selected feature subset;

measures redundancy between two features (via mutual information or Pearson correlation);

quantifies distributional divergence of the selected subset under different conditions (measured by Jensen–Shannon or Wasserstein distance);

are balancing parameters controlling redundancy and invariance constraints. This formulation integrates three complementary objectives—maximizing robustness, minimizing redundancy, and enforcing cross-condition invariance—within a single optimizable functional, which distinguishes DRFD from heuristic weighted-average approaches. The optimal feature subset is obtained by:

where

K denotes the desired number of selected features. Redundancy minimization and distributional divergence constraints are commonly introduced in robust feature selection and invariant representation learning to enhance generalization under distribution shifts [

39,

40]. These constraints help improve feature robustness across different operational conditions and are key elements of our optimization framework.

3.3.3. Greedy Optimization Algorithm

Because the objective

exhibits monotonicity and approximate submodularity under bounded redundancy, a greedy search yields a near-optimal solution with theoretical guarantees. The marginal gain of adding a candidate feature

to the current subset

is computed as:

which quantifies the incremental improvement in robustness achieved by including

. At each iteration, the feature that maximizes the marginal gain is selected and added to the subset. The procedure repeats until

.

Each iteration requires

computations for redundancy and divergence updates, yielding an overall time complexity of

. As shown in

Section 3.4, the greedy approximation achieves at least

of the optimal objective value. Building on this theoretical foundation, the DRFD algorithm extends traditional feature selection by introducing a robustness-driven optimization framework that explicitly models environmental disturbances. By jointly considering statistical, structural, and distributional properties, the framework enables automated identification of reliable feature subsets with provable performance guarantees, ensuring that the selected features remain discriminative, stable, and generalizable across heterogeneous operating conditions.

3.3.4. Cross-Condition Robustness Metric

To further assess the consistency of recognition accuracy across multiple environments, a relative variance (RV) metric is introduced as:

where

and

represent the mean and standard deviation of recognition accuracy across the three conditions. This indicator quantitatively measures cross-condition stability and is later used in the comparative experiments (

Section 4.3).

3.4. Theoretical Properties of DRFD

The DRFD algorithm serves not only as an empirical feature selection approach but also as a theoretically grounded optimization framework. This section establishes the mathematical properties that guarantee the theoretical reliability and interpretability of DRFD, including monotonicity, approximate submodularity, convergence bound, and computational complexity.

3.4.1. Monotonicity of the Objective Function

Let the objective function

be defined as in

Section 3.3. Under the assumption that redundancy and divergence terms are non-negative and bounded, the objective function exhibits a monotonic non-decreasing behavior with respect to feature set inclusion. This property guarantees that adding a new feature cannot decrease the overall robustness score, thereby ensuring the stability and convergence of the greedy selection procedure.

3.4.2. Approximate Submodularity

The objective function , defined over subsets of the feature pool F, is designed to balance discriminability, stability, and redundancy. Although the inclusion of redundancy-related terms may introduce mild deviations from strict submodularity, the overall objective exhibits approximate submodular behavior when pairwise feature correlations remain bounded. Intuitively, this property implies that the marginal gain obtained by adding a new feature gradually diminishes as the selected feature subset grows. Under such bounded-correlation conditions, standard results from approximate submodular optimization theory indicate that the greedy selection strategy achieves a near-optimal solution with a constant-factor performance guarantee. Specifically, the greedy solution is guaranteed to retain a substantial fraction of the optimal objective value, even in the presence of correlated features. This theoretical property provides a solid foundation for the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed DRFD feature selection framework.

3.4.3. Convergence and Computational Complexity

The greedy iteration described in Algorithm 1 terminates after

K steps. At each iteration, all remaining candidate features are evaluated, and pairwise redundancy information is updated incrementally. As a result, the overall computational cost grows on the order of

, while the memory cost is dominated by the redundancy matrix of size

. In practical implementations, convergence is typically achieved within fewer than 10 iterations for moderate feature pools

50), making the proposed DRFD framework computationally tractable for real-world detection scenarios.

| Algorithm 1 Summarizes the overall process |

| Input: | Candidate feature set ; weights ; coefficients ; desired feature number |

| Output: | Robust feature subset |

| 1. | Initialize ; |

| 2. | Compute single-feature robustness scores for all F via Equation (10); |

| 3. | while do

For each remaining feature , compute marginal gain using Equation (13); Select and update ; Re-evaluate and after each update.

|

| 4. | Return . |

3.4.4. Robustness and Interpretability Guarantee

Beyond algorithmic optimality, the DRFD framework provides explicit guarantees for disturbance-robust interpretability. For each selected feature , the following criteria are satisfied:

- (a)

Statistical Significance: , ensuring inter-condition discriminability;

- (b)

Stability: , guaranteeing resistance to intra-condition fluctuations;

- (c)

Separability: , preserving geometric distinction in embedding space.

These thresholds define an interpretable criterion space in which feature robustness can be visualized or compared across conditions (e.g., roadbed, tunnel, bridge). Thus, DRFD simultaneously provides quantitative rigor and physical interpretability, bridging statistical learning and domain-specific insight. In summary, the DRFD algorithm possesses the following theoretical properties:

- (a)

Monotonicity: The objective function increases with subset expansion;

- (b)

Approximate Submodularity: Guarantees near-optimal selection efficiency;

- (c)

Convergence Guarantee: Ensures bounded runtime and numerical stability;

- (d)

Robustness and Interpretability: Explicitly constrains feature selection under multi-perspective robustness criteria.

These properties collectively confirm that DRFD is not an empirical heuristic but a mathematically grounded and provably effective optimization framework for robust feature selection in disturbed track circuit environments.

4. Experimental Validation and Analysis

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the DRFD framework, comprehensive experiments were conducted using real-world railway monitoring data collected from on-board inspection vehicles. The experimental validation aims to examine the framework’s ability to identify disturbance-robust features and its consistency and interpretability across diverse structural conditions. To ensure statistical rigor and to avoid assumptions of normality under disturbance-rich railway environments, nonparametric statistical tests were systematically employed throughout the experimental analysis, including Kruskal–Wallis tests and Dunn’s post-hoc comparisons, to validate the significance and robustness of the proposed DRFD framework. Building upon the theoretical modeling and algorithmic formulation established in

Section 3, the experimental workflow follows a closed-loop validation procedure comprising three major stages:

- (a)

Feature Construction and Evaluation:

Raw compensation-capacitor signals are first transformed into multi-domain feature representations spanning the time, frequency, and time–frequency domains. These features capture amplitude characteristics, waveform morphology, and spectral behavior under different operating conditions.

- (b)

Robustness Quantification:

Each candidate feature is evaluated from three complementary perspectives, including statistical significance across operating conditions, stability against intra-condition fluctuations, and geometric separability in the embedded feature space. This multi-perspective assessment ensures that only features exhibiting both discriminative power and environmental robustness are retained.

- (c)

Optimization and Verification:

Based on the robustness evaluation results, the proposed DRFD framework automatically selects the most representative feature subset through a structured optimization process. The selected features are subsequently validated under different operating scenarios to assess their generalization capability and robustness in real-world environments.

In the DRFD framework, key hyperparameters were selected based on empirical robustness considerations and engineering constraints. These hyperparameters were tested for stability and robustness across various operational conditions, as demonstrated in the multi-condition experiments presented in

Section 4.

4.1. Data Acquisition and Scenario Segmentation

4.1.1. Data Source and Collection Procedure

The experimental data used in this study were acquired from comprehensive inspection vehicles operating on actual railway lines under normal service conditions. These vehicles are specifically designed for compensation capacitor signal detection and continuously record the induced-voltage responses of the capacitors along the track circuit. The measured signals represent the true compensation capacitor induced voltages, which inherently contain both steady-state characteristics of the track circuit and transient fluctuations caused by structural disturbances and electromagnetic interference. Consequently, the dataset consists of both steady and disturbed responses, providing a realistic reflection of the complex operating environments encountered in real-world railway systems.

The data used in this study were provided by the China Academy of Railway Sciences (CARS), which collected the data under the scope of ongoing railway infrastructure maintenance. Due to confidentiality agreements with CARS, the raw dataset cannot be shared publicly. However, the dataset has been utilized in accordance with all relevant data protection and privacy guidelines, ensuring that the research results are reproducible within the scope of the analysis conducted.

Four independent railway lines were selected to ensure representativeness across diverse infrastructure types and environmental conditions. A statistical summary of the dataset is provided in

Table 1. For each line, the measured signal sequences were divided into discrete track sections according to the mileage records and official segmentation information obtained during data acquisition. Each section contained multiple compensation capacitors, ensuring that the spatial structure of the line was faithfully preserved in the dataset. The total numbers of sections across the four lines were 874, 1245, 1134, and 928, respectively. On average, each section contained 6–15 capacitors, resulting in a sufficiently dense spatial sampling of induced-voltage responses along the lines.

Each track section was then matched to its corresponding operating condition—roadbed, tunnel, or bridge—by cross-referencing mileage records with infrastructure condition tables. This mapping process ensures that each segment of the measured induced-voltage data is accurately aligned with its physical environment, forming a reliable foundation for subsequent robustness validation and DRFD-based feature optimization.

4.1.2. Data Segmentation and Labeling Methodology

To enable feature-based analysis under different structural conditions, the measured compensation-capacitor voltage signals were segmented into uniform temporal sections and subsequently labeled according to their corresponding operating environments. Let

denote the induced-voltage sequence measured along a railway line, where

represents the total sampling interval. The sequence was divided into

non-overlapping segments of equal duration

:

Each segment

contains the complete response of one or several compensation capacitors within a specific track section. For every segment, a feature vector

is extracted by applying the multi-domain operator mapping

:

Here,

collects time-domain, frequency-domain, and time–frequency-domain descriptors such as RMS, PF, CF, and wavelet-energy-based indicators, thereby transforming the raw signal sequence into a structured feature matrix.

To ensure physical interpretability, each segmented signal was aligned with the infrastructure-condition table using the mileage index recorded during data acquisition. By matching the start and end mileage of each segment with the corresponding entries in the condition table, every segment was uniquely labeled as roadbed, tunnel, or bridge. This process guarantees that all feature samples maintain one-to-one correspondence with their actual structural environments. Through this segmentation and labeling procedure, the original continuous signal dataset is transformed into a condition-aware feature dataset that captures both spatial and environmental variability.

4.1.3. Preprocessing and Normalization

Before feature extraction and robustness evaluation, all segmented compensation-capacitor voltage signals underwent a standardized preprocessing and normalization procedure. The objective of this step is to mitigate the effects of measurement errors and random electromagnetic noise while preserving the intrinsic physical characteristics and environment-induced variations of the signals. Under ideal operating conditions, the induced voltage of a compensation capacitor exhibits a distinct single-peak pulse precisely at the capacitor’s spatial location, whereas non-capacitor regions remain near the baseline level. Because compensation capacitors are deployed at uniform spatial intervals along the track, a uniformly moving inspection vehicle would theoretically produce periodically spaced voltage pulses in the time domain.

However, in real-world measurements, such ideal periodicity is often distorted. Structural resonance on bridges, impedance imbalance in tunnels, and coupling interference in roadbeds may result in multi-peak clusters, missing pulses, or broadband high-amplitude bursts that obscure the genuine capacitor responses. Therefore, the preprocessing pipeline aims not to eliminate environmental effects, but rather to restore the underlying physical pulse pattern while suppressing non-physical disturbances.

- (1)

Baseline Correction and Detrending

Each signal segment was first processed to remove low-frequency drift and DC offsets introduced by rail impedance imbalance or power-line coupling. A polynomial detrending operation was applied to stabilize the mean level of each segment without altering the position or amplitude of genuine capacitor-induced pulses. This ensures that subsequent amplitude normalization reflects only the true variation of capacitor responses rather than slow baseline fluctuations.

- (2)

Noise Suppression and Outlier Removal

A critical distinction was made between random noise and environment-induced disturbances. Random noise—originating from transient electromagnetic spikes, sampling jitter, or sensor artifacts—contains no physical information and should be suppressed. In contrast, environmental disturbances represent genuine signal variability due to structural and impedance differences across roadbed, tunnel, and bridge conditions, and must therefore be preserved. To achieve this, an adaptive amplitude-thresholding method was employed to attenuate random, short-duration spikes, while retaining disturbance-related temporal and spectral variations. Segments exhibiting unmeasurable artifacts—such as truncated, saturated, or completely distorted waveforms—were excluded from further analysis. This process ensures that the retained dataset preserves the environment-dependent diversity essential for robustness validation.

- (3)

Amplitude Normalization

To reduce inter-line variations and prevent high-energy segments from dominating feature statistics, all valid segments were amplitude-normalized according to their maximum absolute voltage:

This normalization preserves the waveform morphology while ensuring consistent amplitude scales across all segments, facilitating fair cross-condition comparison.

- (4)

Feature Standardization

After feature extraction using the operator mappings, each feature dimension was standardized to zero mean and unit variance:

where

and

represent the mean and standard deviation of the

j-th feature over the entire dataset. This step guarantees numerical stability and equal contribution of all features to the subsequent robustness evaluation and optimization. Through this carefully designed preprocessing pipeline, the raw capacitor-induced voltage signals—originally containing both genuine and disturbed responses—were transformed into a clean, physically interpretable, and statistically normalized dataset. Importantly, the procedure suppresses measurement-related randomness while retaining the environment-specific characteristics that differentiate bridge, tunnel, and roadbed conditions.

4.2. Robustness Evaluation of Candidate Features

With the preprocessed and normalized dataset obtained in

Section 4.1, this section performs a systematic robustness evaluation of all candidate features extracted from the compensation-capacitor voltage signals. The purpose is to quantitatively determine which features remain statistically discriminative, environmentally stable, and geometrically separable under different structural operating conditions—namely roadbed, tunnel, and bridge. While conventional feature-based analyses often emphasize discriminability alone, they seldom address whether the identified features remain reliable under environmental perturbations or maintain consistent distributions across measurement sessions.

To overcome this limitation, the proposed CCS-TRV framework evaluates each candidate feature through three complementary perspectives. Given that the extracted features may not follow Gaussian distributions under varying structural disturbances, all statistical evaluations in this section are conducted using nonparametric hypothesis tests:

- (a)

Statistical Significance —assesses whether the distributions of differ significantly across operating conditions, as defined by the Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s post-hoc tests;

- (b)

Environmental Stability —measures the intra-condition variability of using the Environmental Stability Index (ESI), thereby capturing its resistance to structural and electromagnetic disturbances;

- (c)

Feature-Space Separability

—quantifies the geometric distinctiveness of feature distributions in the embedded space using t-SNE projection and K-means clustering [

41].

Each of these metrics reflects a unique robustness dimension, statistical significance ensures discriminability, stability ensures consistency, and separability ensures structural distinctness in multidimensional space. Only when a feature simultaneously satisfies all three criteria can it be regarded as truly disturbance-robust and suitable for subsequent DRFD optimization. To facilitate quantitative comparison, all robustness metrics were normalized to the range [0, 1], and the evaluation results were visualized through statistical tables and multi-condition density distributions. This process not only highlights the most representative and resilient features but also reveals potential conflicts between significance, stability, and separability.

4.2.1. Significance Testing Results

All 14 candidate features (see

Table 2) were independently evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) test and Dunn’s post-hoc analysis under three operating conditions (roadbed, tunnel, and bridge). Equal sample sizes were maintained for each condition to ensure unbiased comparison, and the tests were repeated across four railway lines. The aggregated statistics (mean K–W statistic

and average

p-value) were reported. This cross-line and cross-condition analysis ensures that the detected significance is both statistically reliable and consistent across different lines and structural environments.

Table 2 summarizes the global significance analysis of all candidate features. Among the 14 features, RMS, PF, CF, FV, and MSF satisfied the adjusted threshold (

), indicating statistically significant distributional differences across structural conditions. These five features exhibit the strongest inter-condition discriminability and are therefore retained as the core candidates for subsequent robustness evaluation and DRFD optimization.

Future Research Consideration:

While this study focuses on the most statistically significant features, we acknowledge that excluding the least contributing features from the feature set could offer valuable insights into their contribution to overall performance. In future work, we plan to carry out a comparative study to evaluate the impact of excluding these features. This study will explore whether removing the least contributing features improves robustness and stability across different operating conditions and further enhance the generalizability of the feature set.

To better illustrate the statistical results, the three figures (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) present key feature behaviors under the three operating conditions (roadbed, tunnel, and bridge). These figures combine significance scoring and adaptive probability distribution plots to provide insights into the discriminative power, stability, and separability of the selected features. Each figure serves a distinct purpose in analyzing different aspects of the feature performance across diverse environments.

Figure 3 illustrates the statistical significance of each feature across the three operating conditions. The Kruskal–Wallis test is used to assess the overall discriminability of the features, which helps determine whether the distributions of each feature differ significantly across roadbed, tunnel, and bridge conditions. As shown, the features RMS, PF, CF, FV, and MSF exhibit the highest significance scores, indicating substantial distributional divergence between operating conditions. This demonstrates the effectiveness of these features in distinguishing between different railway environments.

Figure 4 provides a detailed decomposition of the statistical significance results using Dunn’s post-hoc pairwise comparison test. It focuses on identifying specific differences between pairs of operating conditions (i.e., bridge vs. roadbed, tunnel vs. roadbed). For example, RMS and CF show the lowest

p-values (below 0.01) between the bridge–roadbed and tunnel–roadbed pairs, confirming their strong separability and ability to distinguish between these conditions. This figure further substantiates the features’ effectiveness in classifying track circuit signals under various environmental influences.

Figure 5 visualizes the feature distributions after applying adaptive kernel density estimation (KDE). Each color in the figure corresponds to a different operating condition: blue for roadbed, orange for tunnel, and green for bridge. This figure demonstrates how the feature distributions shift and deform across conditions, highlighting the amplitude-frequency coupling relationships (e.g., RMS–CF and PF–FV). The distinct shifts in density and the deformation of the feature shapes provide visual evidence of both the discriminative capability and environmental sensitivity of the selected features. This visualization supports the notion that the features are well-suited for robust condition recognition under real-world disturbances.

In summary, these three figures (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) offer a comprehensive view of the selected features’ performance across different operating conditions, focusing on their statistical significance, pairwise separability, and environmental sensitivity. This multi-dimensional analysis ensures that the chosen features are not only statistically significant but also robust and reliable for condition recognition in railway track circuits.

4.2.2. Intra-Condition Stability Evaluation

To evaluate the consistency of feature responses within identical environments, the intra-condition stability was computed for all 14 candidate features using signal data collected under three representative operating conditions (roadbed, tunnel, and bridge). Each feature sample was normalized via z-score scaling before calculating the Environmental Stability Index (ESI) values for each condition and their mean value , ensuring statistical comparability across features. The resulting stability scores were ranked and qualitatively classified into three empirical levels: (i) Stable: > 0.88; (ii) Moderate: 0.83 ≤ ≤ 0.88; (iii) Unstable: < 0.83.

Table 3 presents the computed ESI values

for all features under the three operating conditions, together with their mean ESI values and derived stability scores.

Figure 6 further visualizes these results in the form of a heatmap, where each cell is annotated with its numerical ESI value. Lighter colors indicate lower intra-condition variability (i.e., higher stability), while darker colors represent higher variability and poorer repeatability.

The results reveal that most time-domain features (RMS, PF, CF, MA, and WE) exhibit both low ESI values and high stability scores ( > 0.88), indicating consistent intra-condition responses and strong measurement repeatability. These features are primarily governed by signal amplitude or energy accumulation, which remain relatively invariant under identical excitation, thus reflecting intrinsic circuit stability.

In contrast, frequency-domain features such as FV and MSF display considerable dispersion, especially under the bridge condition. This instability can be attributed to resonance and impedance fluctuations, which amplify small environmental perturbations. Consequently, although FV shows strong inter-condition discriminability (see

Section 4.2.1), its intra-condition reproducibility is limited. Moderate-stability features (Variance, WPER, WMP, and Skewness) are influenced by mixed effects of amplitude fluctuation and phase distortion. While they are not as stable as RMS or PF, they can complement highly stable indicators and contribute to robustness-aware diagnostic models.

The intra-condition analysis confirms that RMS, PF, and CF are the most stable and repeatable features, maintaining consistent behavior across all structural environments. Combined with their high discriminability established in

Section 4.2.1, these features form the core feature subset for robust condition recognition and further DRFD-based validation. Conversely, FV and MSF exhibit strong discriminability but limited intra-condition stability, implying that high significance does not necessarily guarantee robustness.

4.2.3. Feature-Space Separability Analysis

Following the evaluations in

Section 4.2.1 and

Section 4.2.2, this section investigates how effectively the combined feature representations distinguish different operating conditions within a multidimensional feature space. A well-separated feature space is essential for achieving high discriminative capability and ensuring reliable class margins, both of which are critical for accurate condition recognition and robust model generalization. To quantify separability, two complementary statistical metrics are adopted: the Bhattacharyya distance

and the Fisher discriminant ratio

. Both indices measure the degree of overlap between class-conditional feature distributions, thereby reflecting discriminability and compactness.

The separability metrics and were computed for all 14 candidate features across the three representative operating conditions—roadbed, tunnel, and bridge. For each feature, pairwise Bhattacharyya distances were obtained for the (roadbed–tunnel), (roadbed–bridge), and (tunnel–bridge) pairs, and their average value was used to represent the overall separability strength. To facilitate comparison across features, all computed indices were normalized to [0, 1]. They were then mapped onto a two-dimensional validation plane, in which the x-axis corresponds to feature significance , the y-axis to stability , and the color dimension encodes the separability index . This unified visualization enables joint interpretation of significance, stability, and separability within a single figure.

Table 4 summarizes the computed Bhattacharyya distances and Fisher discriminant ratios for all 14 features, together with their qualitative separability levels.

Figure 7a illustrates the global separability distribution of candidate features within the unified validation plane, where statistical significance, environmental stability, and structural separability are jointly evaluated.

Figure 7b presents the three-dimensional scatter distribution of the core features (RMS, PF, and CF) under roadbed, tunnel, and bridge conditions. The feature clusters exhibit distinct spatial separation, demonstrating both high discriminability and consistent robustness across different operating environments. The color intensity represents the averaged separability index

, quantitatively reflecting the degree of class distinction in the feature space.

The results indicate that RMS, PF, and CF exhibit the highest separability scores, consistent with their statistical significance and intra-condition stability discussed in

Section 4.2.1 and

Section 4.2.2. Their feature distributions show well-defined, non-overlapping clusters across operating conditions, verifying their potential as core discriminative indicators. In contrast, MSF and FV, although significant, demonstrate partial overlap in feature space, especially under the tunnel–bridge transition, suggesting that frequency-related features are more sensitive to environmental coupling effects. Features such as Skewness and WPER possess limited discriminative power, primarily due to their low variance-to-mean ratio and redundant information content.

The feature-space separability analysis reinforces that RMS, PF, and CF not only exhibit strong statistical significance and high stability but also maintain clear geometric separability across structural conditions. This three-fold consistency—significance, stability, and separability—confirms their robustness as core diagnostic features for track-circuit condition recognition. Conversely, features with strong significance but poor spatial separability (e.g., FV and MSF) should be cautiously weighted in multi-feature fusion models, as they may introduce redundancy or sensitivity to external perturbations.

4.3. DRFD Optimization and Comparative Evaluation

4.3.1. Algorithmic Implementation and Workflow

On the basis of the multi-perspective validation framework introduced in

Section 4.2, this subsection presents the Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation (DRFD) algorithm, which unifies the three feature-validation dimensions—significance, stability, and separability—into a single optimization process. The DRFD framework is designed to automatically balance statistical distinctiveness and environmental robustness, facilitating the extraction of an optimal feature subset that ensures consistent discriminative capability across varying operating conditions.

- (1)

Conceptual Overview

Traditional feature-selection methods often treat discriminability and robustness as independent objectives, which may lead to either overfitting (due to excessive emphasis on significance) or underfitting (due to excessive emphasis on stability). The DRFD framework addresses this imbalance through a multi-objective fusion strategy, integrating three normalized evaluation indices derived from

Section 4.2.1,

Section 4.2.2, and

Section 4.2.3:

Each feature

is characterized by the triplet

, representing its multidimensional robustness profile. To synthesize these three criteria into a unified metric, the DRFD defines a weighted composite robustness score:

where

, and

denote adaptive weighting coefficients assigned to each validation dimension. These weights are determined through Bayesian optimization to maximize overall recognition accuracy under cross-condition validation.

- (2)

Bayesian Weight Optimization

The optimization objective of DRFD is to identify the optimal triplet

that maximizes the validation accuracy

of the classification model:

subject to:

A Gaussian-process (GP) surrogate model approximates the validation-accuracy landscape, while an Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function guides the Bayesian search toward the most promising regions. The optimization iterates until convergence of or until the change in the weight vector satisfies .

- (3)

Algorithmic Workflow

As shown in Algorithm 2, the overall DRFD process comprises the following five stages:

| Algorithm 2 DRFD Feature Optimization Framework |

| Input: | Feature set |

| Output: | Optimized feature subset |

| 1. | for each feature do |

| 2. | Compute using Section 4.2.1, Section 4.2.2, and Section 4.2.3 |

| 3. | end for |

| 4. | Normalize all to |

| 5. | Initialize weight vector |

| 6. | while not converged do |

| 7. | Compute |

| 8. | Evaluate validation accuracy |

| 9. | Update via Bayesian optimization |

| 10. | end while |

| 11. | Select features with |

| 12. | Return = { | } |

Feature Evaluation Layer-Each feature

is independently assessed in terms of significance

, stability

, and separability

using the procedures from

Section 4.2.

Normalization and Fusion Layer-All indices are normalized to [0, 1] using min–max scaling. The vector forms the robustness descriptor for each candidate feature.

Bayesian Weight Optimization-The weighting vector is iteratively updated to maximize in a cross-condition classification setup.

Feature Distillation Layer-Features with robustness scores exceeding a dynamic threshold. are retained to form the distilled subset . This mechanism suppresses redundant or unstable features while emphasizing consistent and discriminative ones.

Model Verification Layer-The optimized subset is input to a classifier (e.g., SVM, GRU, or ensemble model) to evaluate cross-condition accuracy, precision, and F1-score.

Compared with conventional feature-ranking or simple averaging schemes, the DRFD algorithm offers three key advantages. First, Bayesian optimization adaptively balances discriminability, stability, and separability, eliminating the need for manual parameter tuning. Second, by enforcing inter-feature competition through dynamic robustness thresholds, DRFD effectively suppresses redundant or unstable features. Third, the resulting feature subset

exhibits superior and consistent performance across diverse structural conditions, as verified in

Section 4.3.2, demonstrating strong cross-condition generalization capability.

4.3.2. Comparative Evaluation with Baseline Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation (DRFD) algorithm, comprehensive comparative experiments were conducted against several representative feature-selection baselines. The evaluation aimed to assess improvements in cross-condition recognition accuracy, feature stability, and robustness across distinct operating environments, including roadbed, tunnel, and bridge scenarios.

To explicitly benchmark the proposed DRFD framework against existing representative feature-selection strategies reported in the literature, a comprehensive comparative evaluation was conducted. The selected baseline methods correspond to commonly adopted paradigms in prior studies, including significance-driven selection, heuristic aggregation, wrapper-based optimization, and Bayesian search frameworks. This benchmarking design ensures that the experimental comparison reflects the mainstream methodological landscape summarized in the related work section, thereby enabling a fair and quantitative assessment of the proposed method.

- (1)

Baseline Methods

The comparative evaluation included four representative baseline approaches together with the DRFD framework, which collectively reflect the mainstream feature-selection paradigms reported in the related literature.

- (a)

Significance-Only Selection (SO): Features are ranked solely by their statistical significance (Kruskal–Wallis) [

34]. This method emphasizes discriminability but ignores stability and separability, which can lead to inconsistent selection under noise perturbations. This strategy represents a widely adopted significance-driven feature ranking paradigm commonly used in traditional track-circuit and machinery fault diagnosis studies.

- (b)

Equal-Weighted Averaging (EWA): A non-adaptive ensemble that combines multiple evaluation metrics with equal weights [

29]. Although conceptually simple, it assumes identical contribution from each metric and lacks adaptive weighting.

Such equal-weight aggregation schemes are frequently employed in multi-criteria feature evaluation approaches reported in the literature as heuristic baselines.

- (c)

Sequential Feature Selection (SFS): A greedy wrapper algorithm that iteratively adds features to maximize validation accuracy [

42]. While effective in stationary scenarios, SFS is prone to overfitting and unstable ranking under environmental noise. SFS is a classical wrapper-based benchmark method and has been extensively used in prior feature selection studies for performance-oriented optimization.

- (d)

Bayesian Optimization–Feature Selection (BOFS): A global search framework using Gaussian-process–based optimization to maximize classifier accuracy [

28,

29]. However, as pointed out in recent robustness analyses of LASSO-based and Bayesian feature-selection methods, such optimization frameworks often lack explicit robustness or separability constraints, resulting in suboptimal generalization when exposed to environmental disturbances. This class of Bayesian optimization–driven feature selection methods represents recent global-search-based approaches widely investigated in the literature.

- (e)

DRFD: The proposed multi-dimensional optimization framework jointly balances discriminability, stability, and separability through adaptive Bayesian weighting and dynamic robustness thresholding, ensuring optimal feature retention under varying disturbance patterns. Unlike the above baseline methods, DRFD explicitly incorporates disturbance robustness as an optimization objective rather than treating it as an implicit byproduct of accuracy maximization.

- (2)

Experimental Setup

All algorithms were implemented under identical conditions using the same feature dataset, classifier configurations, and evaluation protocols. Three classifiers—Support Vector Machine (SVM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Random Forest (RF)—were employed to verify the generalization capability of the selected features across diverse model architectures. Each classifier was trained on 70% of the dataset and evaluated on the remaining 30% using cross-condition validation, ensuring that the test data originated from unseen structural environments. Performance was quantified by three metrics: Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pre), and F1-score (F1).

- (3)

Quantitative Results and Analysis

The comparative results are summarized in

Table 5, which reports the averaged performance across the three classifiers. As observed, DRFD consistently outperforms all baseline methods in terms of accuracy, precision, and F1-score. On average, DRFD achieves a 4.2% to 7.8% improvement in recognition accuracy and a 6.5% increase in F1-score compared to the best-performing baseline (BOFS). These improvements are particularly significant under tunnel conditions, where environmental coupling effects are stronger, confirming DRFD’s robustness against electromagnetic and structural disturbances. This result demonstrates how DRFD not only improves general recognition accuracy but also enhances cross-condition performance, especially in challenging environments like tunnels and bridges, which pose substantial disturbances for other methods.

In contrast to feature-selection strategies commonly reported in previous studies, which primarily focus on either discriminability or accuracy optimization, the proposed DRFD framework integrates environmental stability and geometric separability into its optimization objective, demonstrating superior robustness and stability across varying environmental conditions.

In comparison with simpler baseline methods such as SO and EWA, DRFD demonstrates even larger improvements, showing an approximate 7% increase in accuracy and a 5% improvement in F1-score compared to EWA, and a significant 8% boost in accuracy compared to SO. These improvements highlight DRFD’s ability to incorporate environmental stability and separability into its optimization framework, overcoming the limitations of simpler methods that primarily focus on statistical significance alone.

- (4)

Cross-Condition Stability and Robustness

Figure 8a shows the recognition accuracy of all evaluated methods under different operating conditions (roadbed, tunnel, and bridge). As shown, DRFD consistently achieves the highest and most stable performance, significantly outperforming all baseline methods. This demonstrates DRFD’s ability to maintain high performance across diverse environmental conditions.

Figure 8b further compares the cross-condition stability of these methods using the relative variance (RV) metric, which quantitatively characterizes robustness. The DRFD achieves the smallest RV (<0.015), indicating the most consistent performance among all compared methods. In particular, DRFD significantly reduces performance variability under tunnel and bridge conditions, which are prone to high electromagnetic disturbances, as shown by its much smaller RV values compared to EWA and SFS. This result supports the theoretical expectation that adaptive Bayesian weighting promotes balanced feature selection and enables DRFD to adapt well to varying disturbance patterns across different structural environments.

Compared to conventional feature-selection strategies, the DRFD framework integrates significance, stability, and separability within a unified optimization scheme and employs Bayesian optimization to adaptively tune weighting coefficients, thereby improving generalization under unseen operating conditions. By retaining only features exceeding a dynamic robustness threshold, DRFD suppresses noise-sensitive and redundant dimensions, ensuring stable recognition in disturbance-rich environments. Overall, the comparative evaluation confirms that DRFD achieves higher accuracy, lower variability, and superior robustness than all baseline methods. These results validate DRFD’s practical suitability for real-world track-circuit condition recognition, where signals are inherently influenced by diverse structural and electromagnetic environments.

4.3.3. Application Validation and Scenario Analysis

To verify the practical applicability and environmental adaptability of the proposed DRFD framework, field validation was conducted using real track-circuit monitoring data collected from three representative structural environments: roadbed sections with stable grounding impedance and low electromagnetic coupling, tunnel sections characterized by structural vibration coupling and transient resonance effects, and bridge sections exhibiting strong electromagnetic interference, multipath propagation, and signal attenuation. This validation evaluates whether the DRFD-distilled feature subset maintains consistent discriminative capability across heterogeneous environments, thereby demonstrating its feasibility for large-scale deployment in railway signal inspection systems.

- (1)

Real-World Deployment Setup

The validated system was deployed on a track-circuit inspection vehicle equipped with an onboard data acquisition unit and a real-time signal processing module. During field operations, the induced voltage signals were continuously sampled at a rate of 100 kHz to ensure high-resolution capture of transient variations.

- (2)

Scenario-Specific Performance Evaluation

To evaluate environmental robustness, DRFD was tested under three representative operational scenarios.

Table 6 summarizes the performance of the proposed framework under real-world track conditions.

Across all test sites, DRFD achieved over 95% recognition accuracy, with less than 0.8% variation across environments. This confirms its high stability and strong resistance to both mechanical and electromagnetic disturbances. These results validate the framework’s ability to jointly balance feature discriminability and environmental robustness, even under non-ideal field conditions.

- (3)

Comparative Scenario Analysis

Figure 9a,b and

Table 7 jointly illustrate the temporal–spatial consistency and cross-line generalization performance of the DRFD framework. As shown in

Figure 9a, the temporal variation of recognition accuracy across sequential detection frames remains below 1%, indicating minimal performance drift and excellent temporal stability during continuous operation. To further evaluate spatial generalization,

Figure 9b and

Table 7 summarize the cross-line recognition results when the model was trained and tested on different railway lines. Specifically,

Table 7 reports the recognition accuracies obtained by DRFD and four baseline methods (SO, EWA, SFS, BOFS) across five representative train–test configurations. The results demonstrate that DRFD consistently achieves the highest cross-line recognition accuracy, maintaining above 94% accuracy even when applied to unseen railway lines (e.g., Line 1 → Line 3, Line 1 → Line 5, and Line 5 → Line 3).

These outcomes confirm DRFD’s robust generalization capability and environmental adaptability, effectively handling variations in structural resonance, electromagnetic interference, and hardware configuration.

The results indicate that the DRFD framework not only maintains superior within-line performance but also exhibits remarkable stability in cross-line transfer scenarios, where the average accuracy remains above 94.5%—a clear improvement of 5–8% over traditional baselines. Such robustness underscores DRFD’s ability to generalize across unseen infrastructure configurations and operational conditions, which is critical for scalable railway signal monitoring systems.

- (4)

Engineering Implications

From an engineering perspective, the DRFD framework offers several advantages for railway signal maintenance and monitoring systems. By continuously tracking feature-space robustness indicators, DRFD enables early awareness of capacitor degradation and signal drift, thereby supporting predictive maintenance. Once trained, the framework operates without environment-specific recalibration, substantially reducing maintenance and deployment overhead in large-scale railway networks. Moreover, its modular design allows seamless integration with existing Line Electronic Units (LEUs) and track-circuit monitoring subsystems, supporting both onboard inspection vehicles and ground-based deployment scenarios.

In summary, the application validation and scenario analysis confirm that the DRFD framework not only enhances recognition accuracy and robustness in controlled experiments, but also demonstrates engineering practicality in real-world deployment. Its strong adaptability to environmental disturbances and cross-line generalization capability underscore its potential as a core algorithm for next-generation intelligent railway signal monitoring and maintenance systems.

4.4. Time–Frequency Analysis and Physical Interpretation

To further elucidate the physical mechanisms underlying the discriminative features distilled by the DRFD framework, a time–frequency analysis was conducted to examine the spectral evolution of compensation-capacitor induced-voltage signals under representative operating conditions. While

Section 4.3 quantitatively assessed feature separability in the reduced space, the present analysis interprets the signal behaviors in the original electromagnetic domain, thereby linking algorithmic features to measurable physical phenomena.

- (1)

Time–Frequency Characterization Across Operating Conditions

Each recorded voltage waveform was transformed into the time–frequency domain using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) with a 512-point Hamming window and 75% overlap. The analysis focused on the characteristic carrier band of 5.75–5.85 kHz, where the induced energy of the compensation-capacitor signal is most concentrated. The resulting spectrograms are presented in

Figure 10a–e, corresponding to the roadbed, tunnel, bridge, and two transition conditions (tunnel → roadbed, bridge → roadbed).

Roadbed Condition (Stable Field): The spectrogram displays a single, narrow ridge centered around 5.8 kHz with minimal amplitude fluctuation, indicating stable grounding impedance and negligible vibration coupling. This behavior corresponds to compact feature clustering and low-variance statistics observed in

Figure 7, confirming the electromagnetic stability of the roadbed environment.

Tunnel Condition (Electromagnetic Interference): The energy distribution becomes dispersed, showing intermittent sidebands and random energy patches due to multipath propagation and attenuation effects. The locally distorted ridges reveal temporal instability, consistent with the broadened feature distribution and elevated PF variance seen in clustering results.

Bridge Condition (Vibration Coupling): Pronounced amplitude modulation and transient spectral broadening appear, reflecting dynamic structural resonance. The wideband expansion of energy bands and intensity oscillations indicate high-frequency coupling interference, explaining the higher CF and RMS values obtained in

Section 4.3.

Transition Conditions (Tunnel → Roadbed and Bridge → Roadbed): In the initial segment of the signal, the spectra exhibit unstable, broadened ridges that gradually converge into a narrowband pattern as the environment transitions to the roadbed.

This evolution verifies the real-time sensitivity of the DRFD framework to environmental changes and its ability to capture signal recovery trends adaptively.

- (2)

Quantitative Spectral Analysis

To further quantify the spectral differences observed in

Figure 10a–e, the average spectral energy and relative energy variance within the 5.75–5.85 kHz band were statistically compared, as illustrated in

Figure 11. The average spectral energy (left axis, blue) represents the dominant amplitude response of the signal, whereas the relative energy variance (right axis, gray) captures normalized spectral fluctuation intensity. For each condition, mean values and confidence intervals (

±σ for energy,

±Δ for variance) were calculated from all valid experimental samples.

As shown in

Figure 11, the roadbed condition exhibits the lowest mean energy (≈−14 dB) with minimal variance, confirming its stable electromagnetic environment. The tunnel condition presents moderately higher energy (≈−12 dB) and larger fluctuation, reflecting partial distortions from reflective interference. The bridge condition shows the highest energy (≈−9.5 dB) and the largest fluctuation range, consistent with strong resonance coupling and mechanical vibration effects. These quantitative distinctions align with the time–frequency observations in

Figure 10, reinforcing that environmental structure governs both the energy concentration and the temporal stability of induced-voltage signals.

- (3)

Physical Interpretation and Correlation with DRFD Features

The observed spectral behaviors substantiate the physical relevance of the three core features extracted by the DRFD framework. Specifically, the RMS reflects the overall energy concentration of the induced-voltage signal and tends to decrease under attenuation and multipath interference, as commonly observed in tunnel environments. The PF characterizes transient spikes arising from dynamic structural vibration and coupling resonance, which are most pronounced under bridge conditions. In contrast, the CF describes the migration of the spectral center, exhibiting upward shifts under resonance-induced harmonic enrichment and downward shifts in attenuated electromagnetic fields.

The observed spectral behaviors substantiate the physical relevance of the three core features extracted by the DRFD framework: These correspondences demonstrate that the DRFD-distilled features are not merely statistical constructs but encapsulate tangible electromagnetic phenomena. In particular, the preservation of narrowband localization under roadbed conditions and its degradation under tunnel and bridge conditions highlight the model’s robustness to environmental perturbations and the physical interpretability of its extracted features.

Overall, the time–frequency analysis bridges the gap between algorithmic discriminability and physical interpretability. It confirms that the DRFD framework effectively captures real electromagnetic characteristics—including amplitude stability, spectral diffusion, and harmonic coupling—that dictate the observed distinctions among roadbed, tunnel, and bridge environments. This alignment between feature-space behavior and signal-space physics further validates the reliability and generalizability of the proposed method for field-deployed track-circuit monitoring systems.

4.5. Discussion and Engineering Implications

The experimental results demonstrate that the DRFD framework achieves not only high discriminability among operating conditions but also consistent performance across diverse electromagnetic and structural environments. By jointly integrating discriminability, robustness, and feature distillation, the extracted features remain invariant to transient spectral diffusion, amplitude perturbations, and vibration coupling. Time–frequency analyses further confirm that the selected features (RMS, PF, and CF) faithfully capture physically meaningful induced-voltage behaviors, such as energy dispersion, harmonic drift, and resonance effects, validating both the robustness and interpretability of the proposed framework.

In practical railway maintenance scenarios, the DRFD framework enables early detection of compensation capacitor degradation or drift by continuously monitoring feature-space robustness indicators, thereby supporting predictive maintenance and reducing unscheduled downtime. When deployed on onboard inspection vehicles, the framework supports real-time fault identification, significantly reducing reliance on manual inspection. Owing to its robustness against environmental variability, DRFD operates effectively across roadbed, tunnel, and bridge environments without environment-specific recalibration, facilitating automated and large-scale deployment. Moreover, its modular design allows seamless integration with existing track-circuit inspection infrastructure.

Despite these advantages, further validation under extreme operating conditions such as severe weather, rail corrosion, and complex electromagnetic interference is still required. Future work will focus on improving adaptive learning capability and computational efficiency for embedded deployment, while extending the robustness-driven feature evaluation paradigm to other disturbance-critical signal analysis tasks.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a Disturbance-Robust Feature Distillation (DRFD) framework for compensation-capacitor signal recognition and fault diagnosis in jointless track circuits. Unlike conventional approaches that focus primarily on model architecture optimization, DRFD emphasizes physically interpretable and disturbance-robust feature modeling. Through a multi-level evaluation pipeline combining statistical significance, intra-condition stability, and geometric separability analyses, RMS, PF, and CF are identified as the most robust indicators for capacitor-state characterization.