Railway Signal Relay Voiceprint Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Swin-Transformer and Fusion of Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Work

1.2. Research Results

1.3. Paper Structure

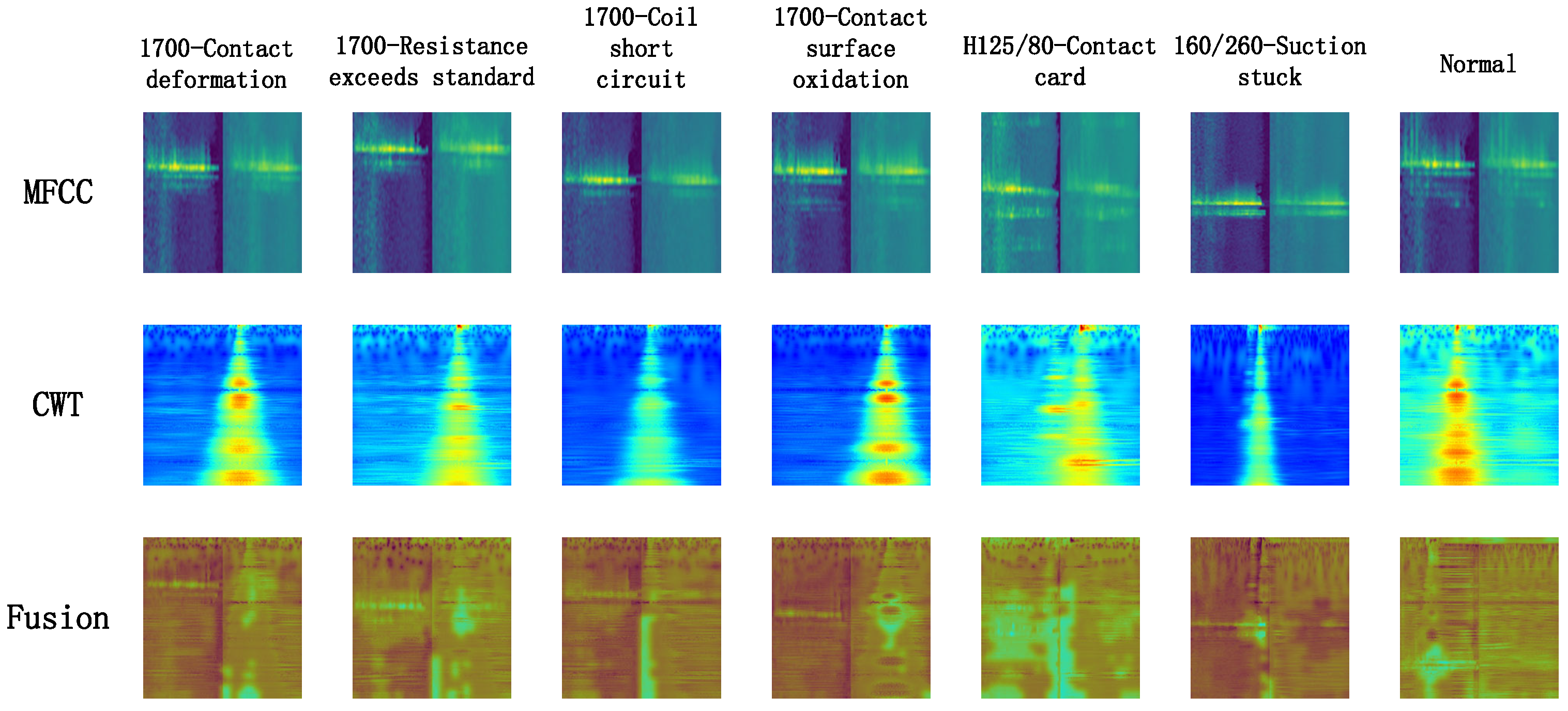

2. Feature Extraction and Fusion

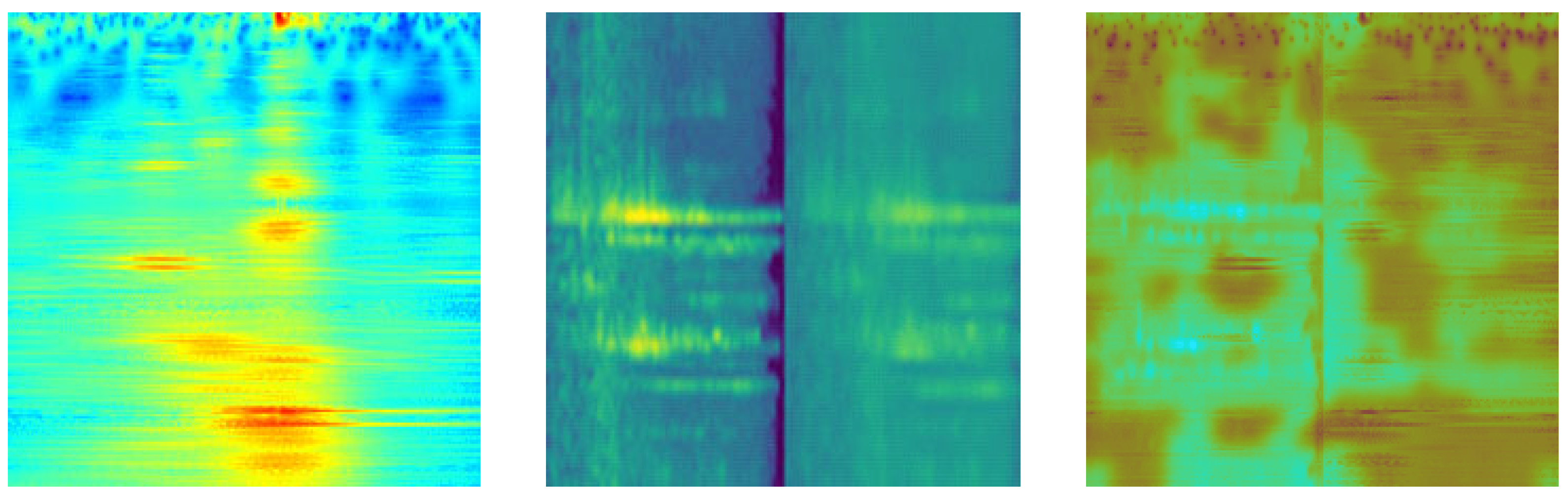

2.1. MFCC

2.1.1. Framing

2.1.2. Windowing

2.1.3. FFT

2.1.4. Mel Filter

2.1.5. DCT

2.2. CWT

2.2.1. Wavelet Basis Function Selection

2.2.2. Wavelet Coefficient Calculation

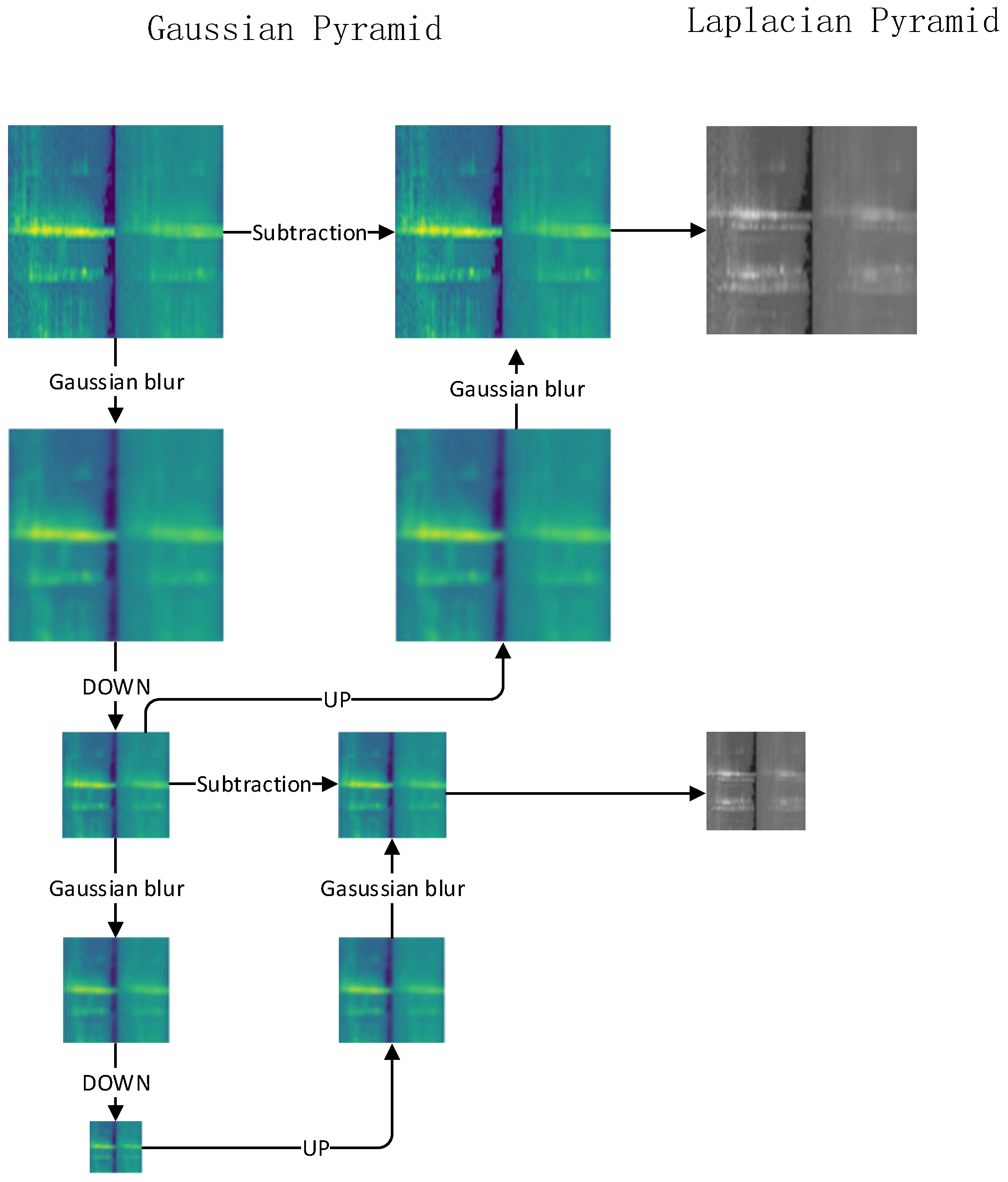

2.3. Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid

2.3.1. Gaussian Pyramid

2.3.2. Laplace Pyramid

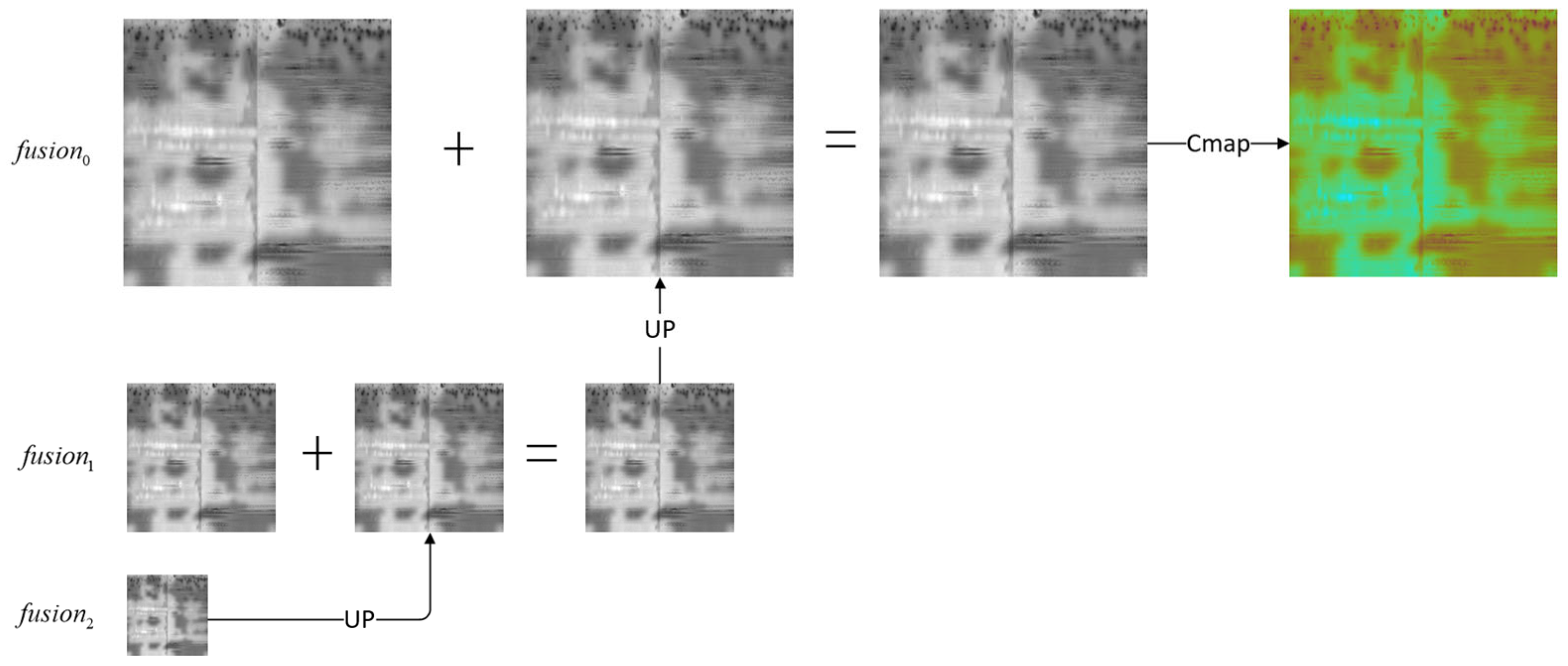

2.3.3. Spectral Graph Fusion

2.3.4. Reconstruction

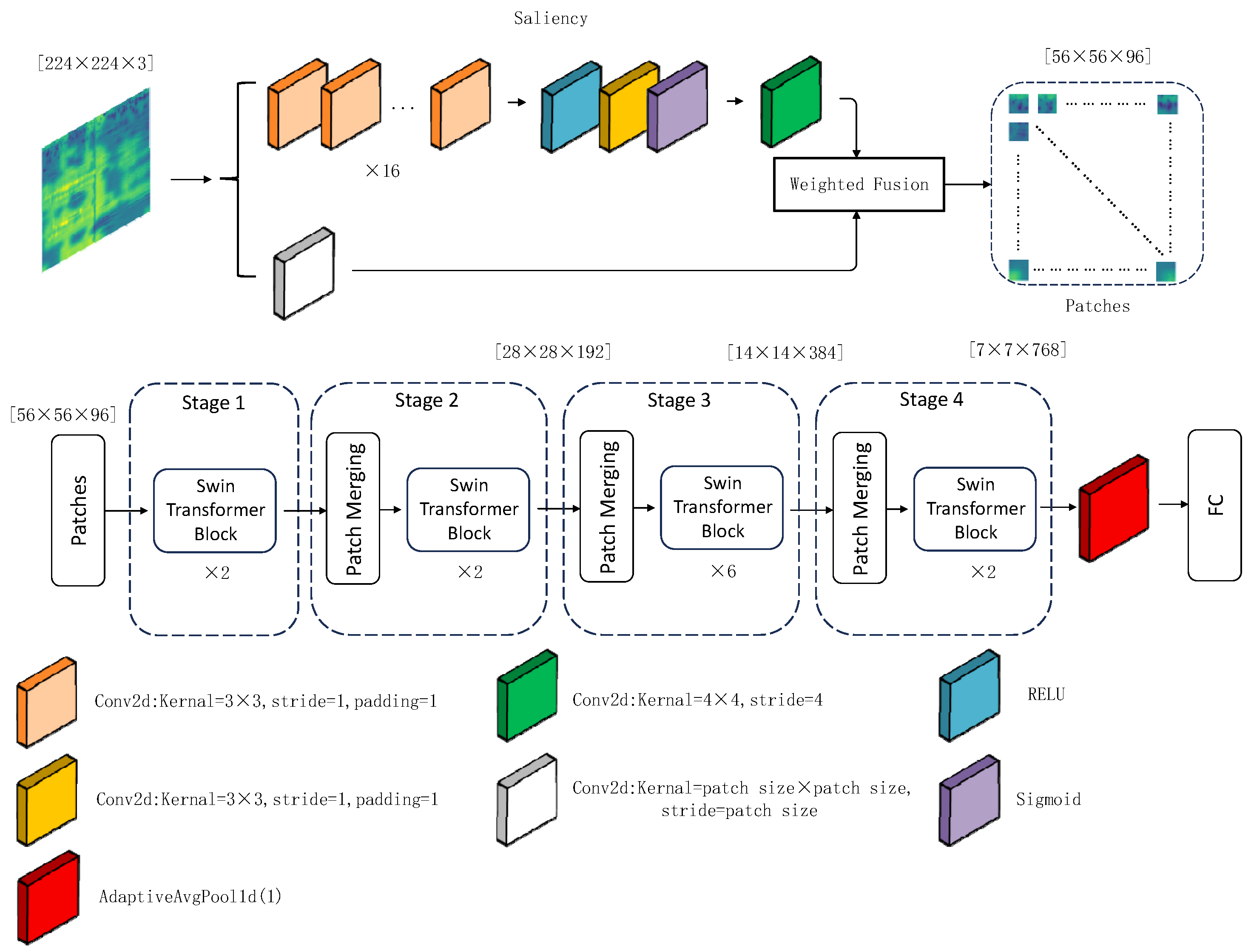

3. Model

3.1. Significance Boosting Module

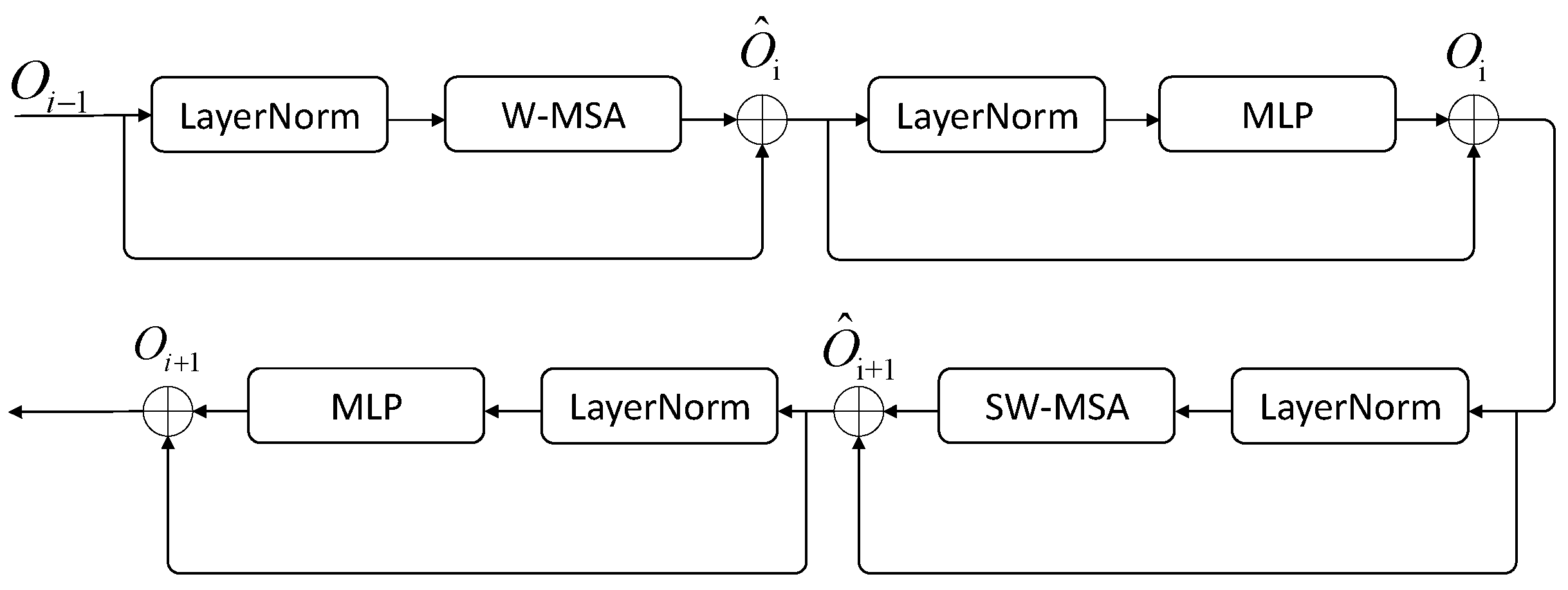

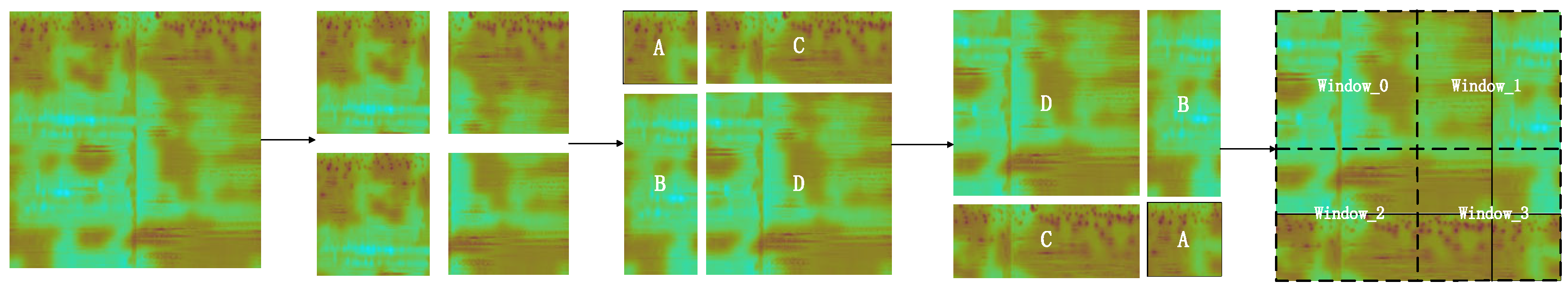

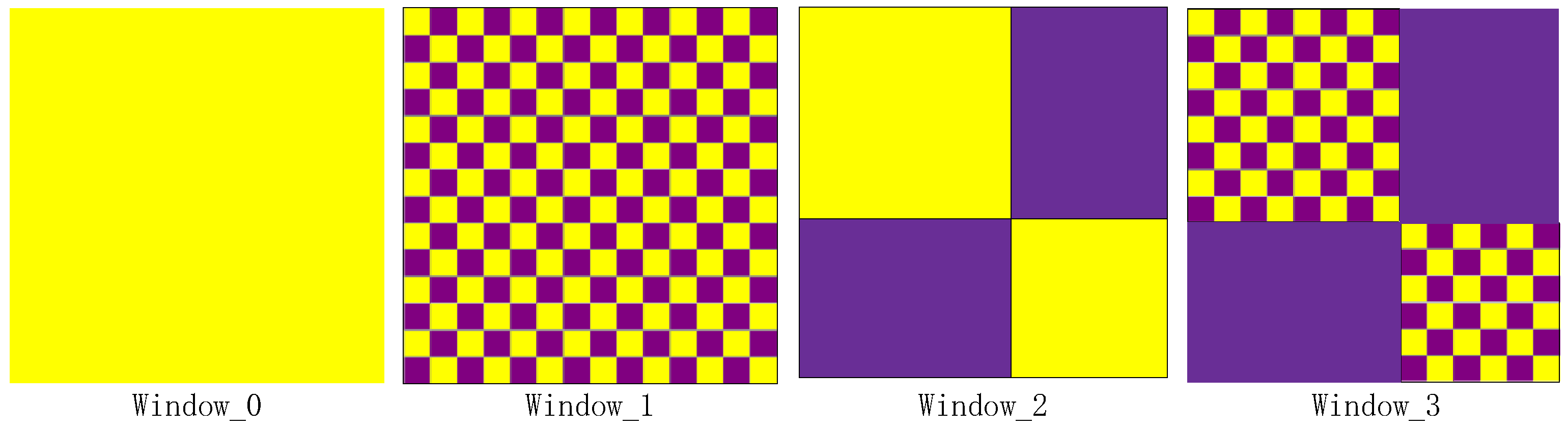

3.2. Swin-Transformer Block

3.3. Classification Process

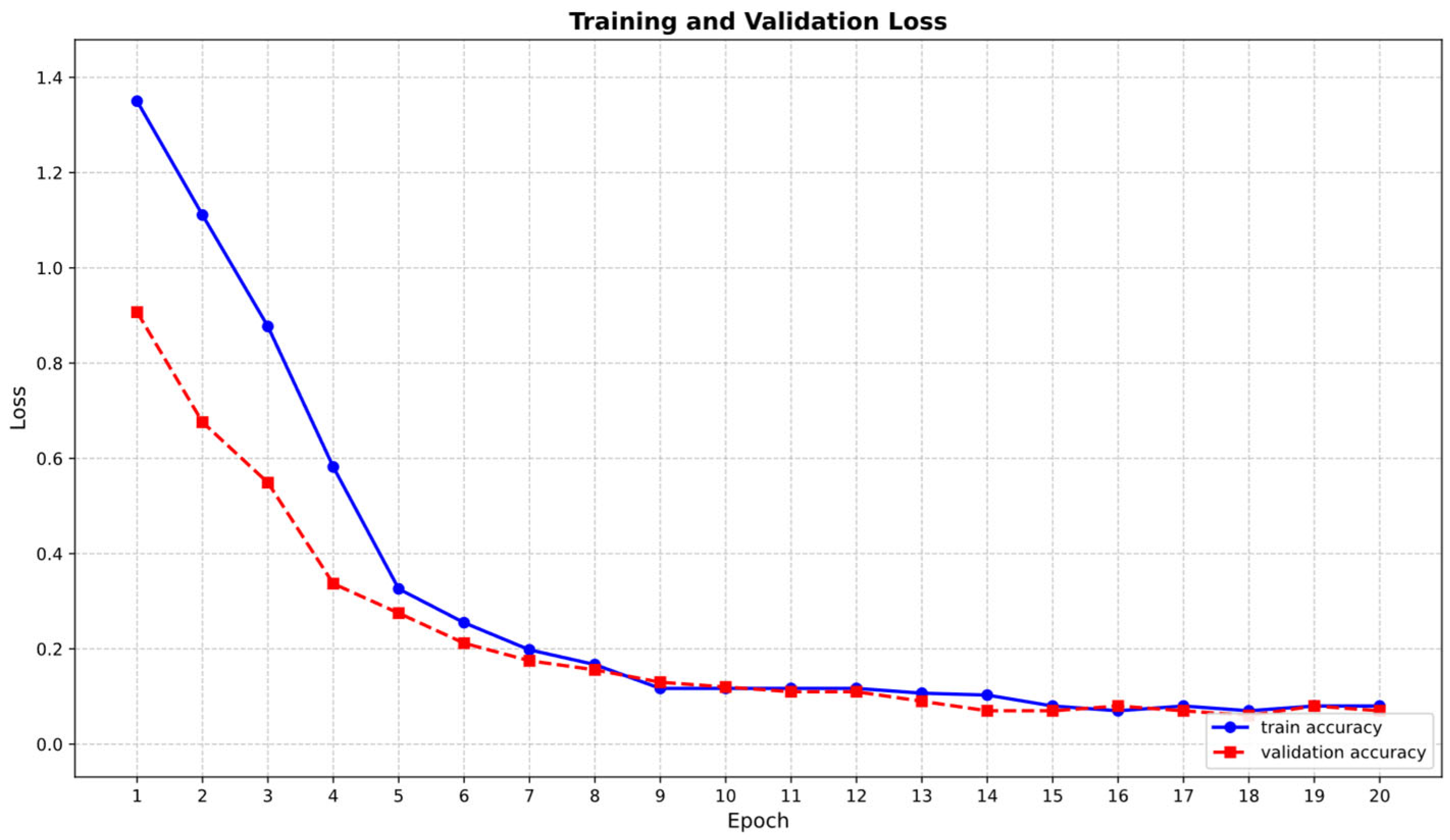

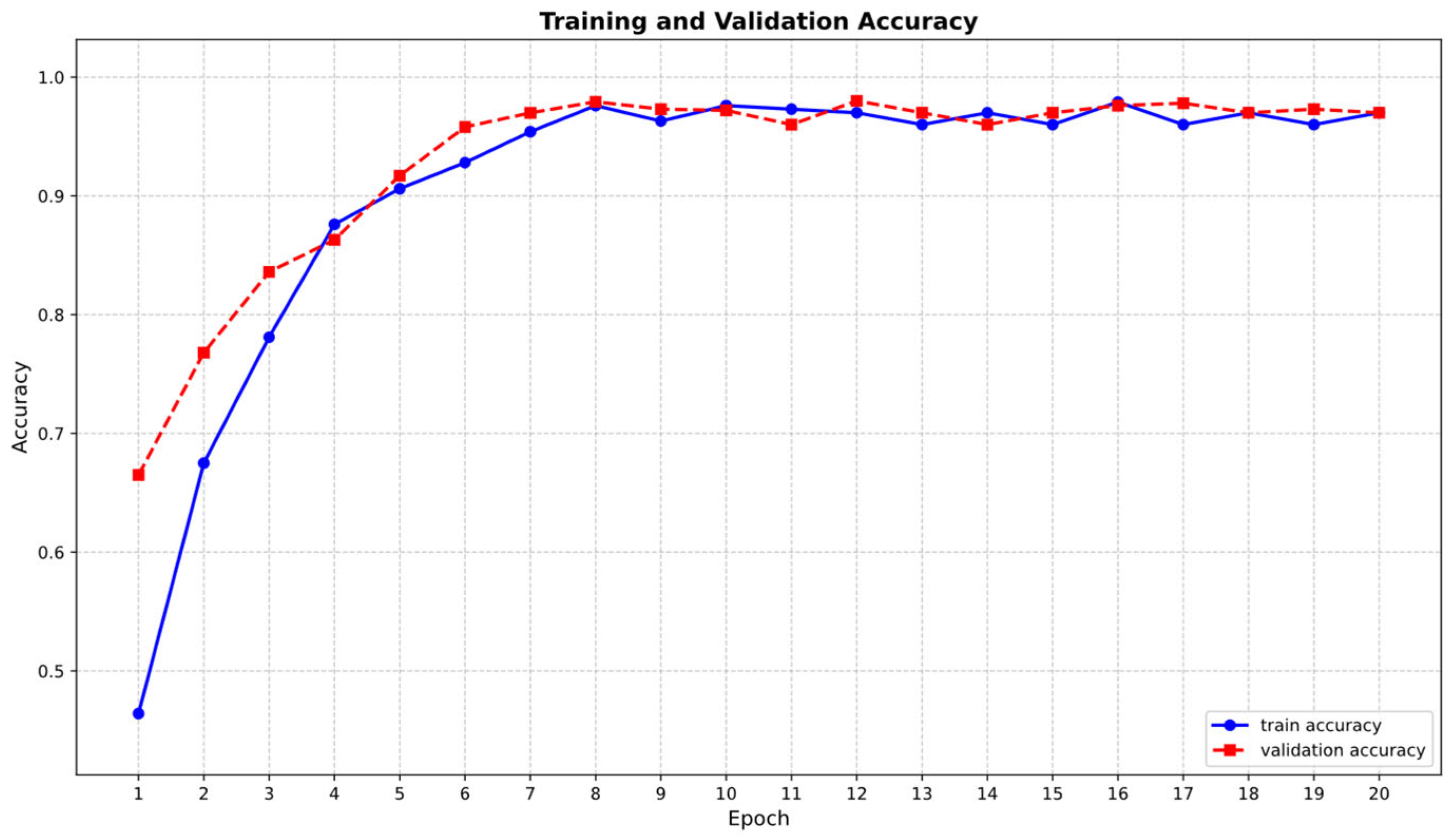

4. Experiment

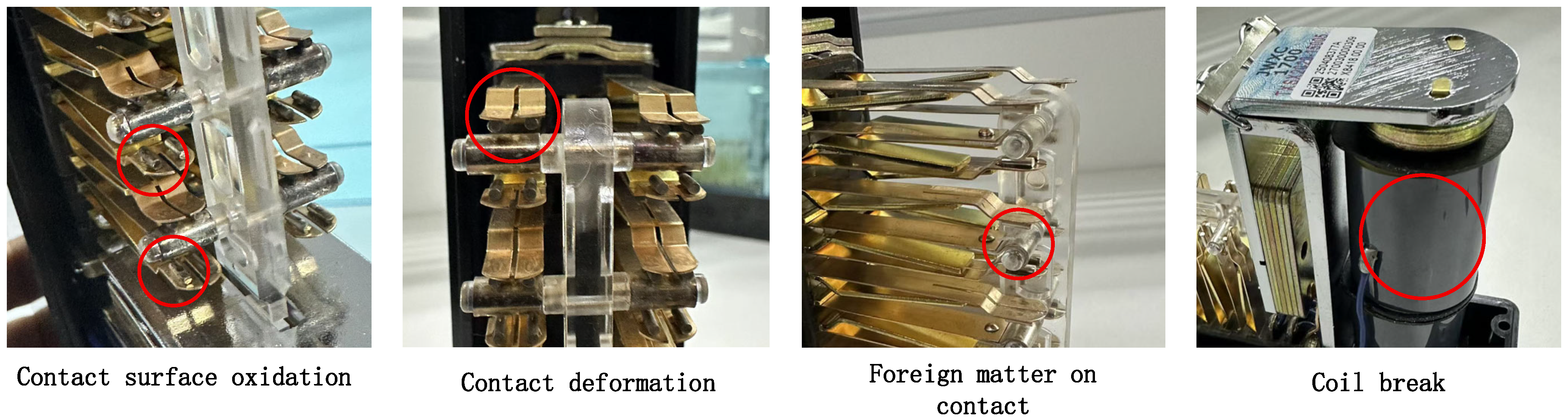

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Comparative Experiment

4.3. Ablation Experiments

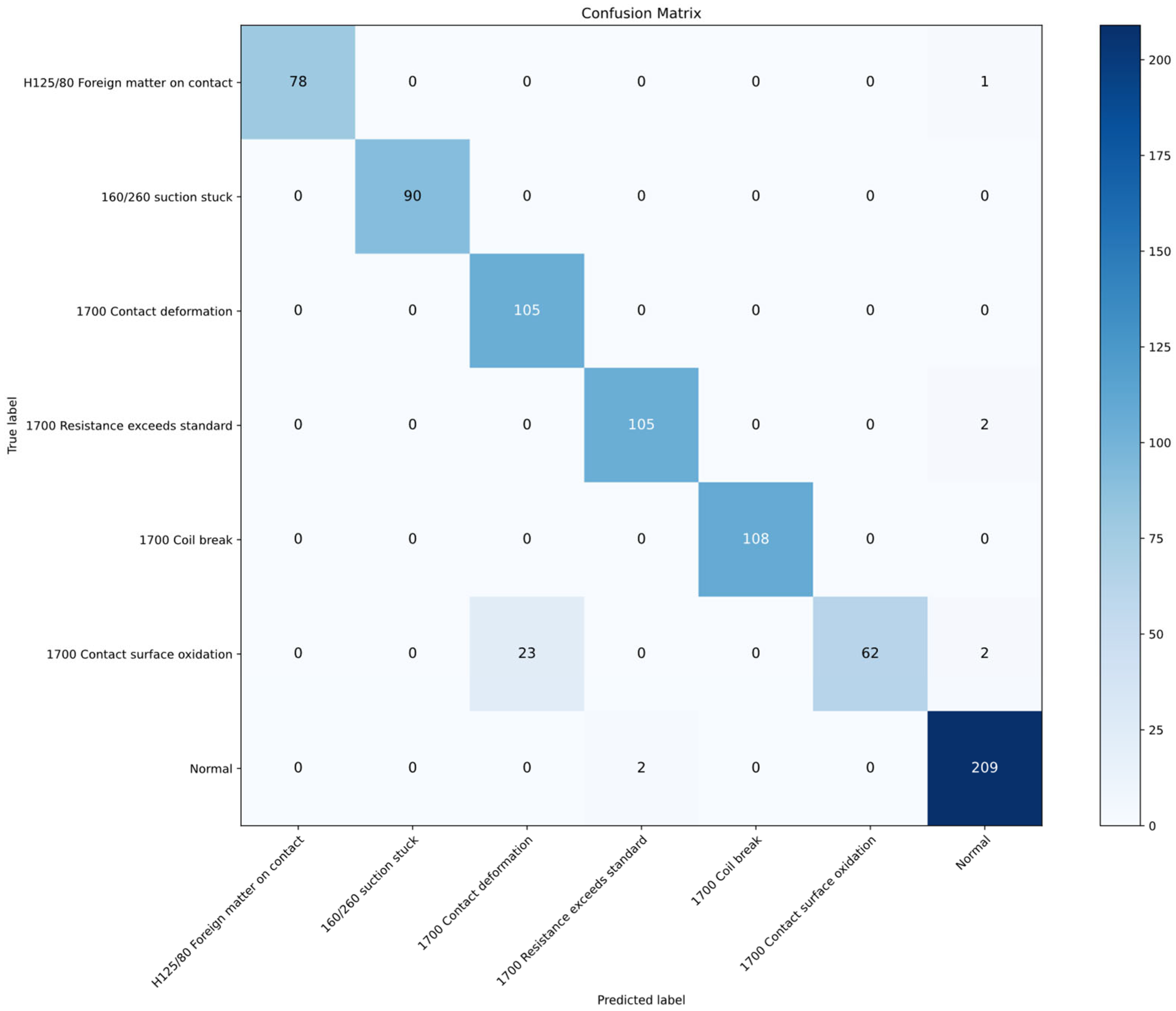

4.4. Confusion Matrix

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| IMF | Intrinsic Mode Function |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MFCC | Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficient |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| Swin | Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows |

| I-Swin | Improved-Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows |

| GRU | Gate Recurrent Unit |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| ResNet | Residual Networks |

| W-MSA | Window-Multi-head Self Attention |

| SW-MSA | Shifted Window-Multi-head Self Attention |

| DCT | Discrete Cosine Transform |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| AST | Audio Spectrogram Transformer |

References

- Song, H.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Tan, L.; Dong, H. Functional Safety and Performance Analysis of Autonomous Route Management for Autonomous Train Control System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 13291–13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Dong, H. Train-Centric Communication Based Autonomous Train Control System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Guo, F. A Dynamic Voiceprint Fusion Mechanism with Multispectrum for Noncontact Bearing Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 8710–8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunson, N.; Marshall, D.; McInnes, F.; Jack, M. Usability evaluation of voiceprint authentication in automated telephone banking: Sentences versus digits. Interact. Comput. 2011, 23, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Z. Study and implementation of voiceprint identity authentication for Android mobile terminal. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Shanghai, China, 14–16 October 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Yue, L.; Wang, W.; Xiangyan, Z. Research on End-to-end Voiceprint Recognition Model Based on Convolutional Neural Network. J. Web Eng. 2021, 20, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lu, H.; Han, S.; Zhao, X. A Novel Causal Federated Transfer Learning Method for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis Based on Voiceprint Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 35573–35584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Sheng, G.; Jiang, X. A Deep Learning Algorithm for Power Transformer Voiceprint Recognition in Strong-Noise and Small-Sample Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Niu, B.; Zhang, X. Automatic Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis System for Power Transformers Based on Voiceprint Recognition. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Tan, H.; Li, C. Recognition of short-circuit discharge sounds in transmission lines based on hybrid voiceprint features. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Internet of Things, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (IoTAAI), Guangzhou, China, 26–28 July 2024; pp. 200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, Z. Research on Voiceprint Recognition Method of Hydropower Unit Online-State Based on Mel-Spectrum and CNN. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December 2024; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mushi, R.; Huang, Y.-P. Assessment of Mel-Filter Bank Features on Sound Classifications Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 26–28 August 2021; pp. 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Shia, S.E.; Jayasree, T. Detection of pathological voices using discrete wavelet transform and artificial neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Techniques in Control, Optimization and Signal Processing (INCOS), Srivilliputtur, India, 23–25 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, L.; Liao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Gong, X. Research on Voiceprint Recognition Based on MFCC-PCA-LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Big Data, Information and Computer Network (BDICN), Xishuangbanna, China, 6–8 January 2023; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Parisotto, S.; Calatroni, L.; Bugeau, A.; Papadakis, N.; Schönlieb, C.-B. Variational Osmosis for Non-Linear Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process 2020, 29, 5507–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, O.; Srivastava, R.; Khare, A. Biorthogonal wavelet transform based image fusion using absolute maximum fusion rule. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Information & Communication Technologies, Thuckalay, India, 11–12 April 2013; pp. 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Jian, Z.; Jie, L. Research on Image Fusion Rules Based on Contrast Pyramid. In Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Shengyang, China, 20–22 December 2018; pp. 1361–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Gulsoy, E.K.; Gulsoy, T.; Ayas, S.; Kablan, E.B. Remote Sensing Scene Image Classification with Swin Transformer-Based Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 9th International Symposium on Innovative Approaches in Smart Technologies (ISAS), Gaziantep, Turkiye, 27–28 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, C. Fault diagnosis of rolling bearings based on dual-channel Transformer and Swin Transformer V2. In Proceedings of the 2024 43rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 4828–4834. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H.; Ma, L.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y. A Dual-Channel Decision Fusion Framework Integrating Swin Transformer and ResNet for Multi-Speed Gearbox Fault Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th Conference on Fully Actuated System Theory and Applications (FASTA), Nanjing, China, 4–6 July 2025; pp. 1469–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.; Wang, B.; Zhu, G.; Wu, J. Efficient Faster R-CNN: Used in PCB Solder Joint Defects and Components Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering Technology (CCET), Beijing, China, 13–15 August 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abulizi, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Sun, H.; Ji, C.; Li, Z. Research on Voiceprint Recognition of Power Transformer Anomalies Using Gated Recurrent Unit. In Proceedings of the 2021 Power System and Green Energy Conference (PSGEC), Shanghai, China, 20–22 August 2021; pp. 743–747. [Google Scholar]

- Hongming, L.; Zhang, K.; Han, S. A Comparison of CNN-Based Transformer Fault Diagnosis Methods Based on Voiceprint Signal. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 13th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference (DDCLS), Kaifeng, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 819–824. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Feng, B.; Xiao, J.; Zheng, W. Voiceprint Diagnosis Method for Urban Rail Power Transformers Based on Mel Spectrogram and Improved Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Software Engineering and Computer Science (CSECS), Taicang, China, 21–23 March 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cappellazzo, U.; Falavigna, D.; Brutti, A.; Ravanelli, M. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning of Audio Spectrogram Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 34th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), London, UK, 22–25 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Author | Feature Extraction Methods | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. Mao et al. | Mel spectrum [9]. | Mel spectrometers offer higher resolution for low frequencies and lower resolution for high frequencies. | Phase information was completely discarded. |

| R. Mushi et al. | Features of the Mel filter [10]. | Effective dimensionality reduction was achieved, reducing the computational load. | Time resolution and frequency resolution cannot be achieved simultaneously. |

| S. E. Shia et al. | Based on wavelet transform [11]. | Capable of providing variable time-frequency resolution. | The choice of wavelet basis depends on prior knowledge and experience. |

| L. Xiong et al. | MFCC and ΔMFCC [12]. | Features are highly compact and solution-related. | Sensitive to noise. |

| Train | Val | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JWXC-1700 Contact deformation | 849 | 105 | 105 | |

| JWXC-1700 Resistance exceeds standard | 870 | 108 | 108 | |

| JWXC-1700 Coil break | 871 | 108 | 108 | |

| JWXC-1700 Contact surface oxidation | 816 | 102 | 102 | |

| JWJXC-H125/80 Foreign matter on contact | 633 | 79 | 79 | |

| JYJXC-160/260 suction stuck | 728 | 90 | 90 | |

| Normal (All relays) | JWXC-1700: | 1523 | 152 | 152 |

| JWJXC-H125/80: | 283 | 28 | 28 | |

| JYJXC-160/260: | 326 | 33 | 33 | |

| Normal class sum | 2132 | 213 | 213 | |

| Method | Accuracy | Recall | F1 | Number of Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-Swin | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.957 | 37.4 M |

| Res-FD-CNN | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.901 | 21.8 M |

| GRU | 0.827 | 0.827 | 0.825 | 1.2 M |

| MobileNet | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.918 | 3.5 M |

| ViT | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.969 | 86 M |

| AST | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 86 M |

| Model | FLOPs | Time Required to Train One Epoch | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-Swin | ~4.9 G | 14 s | 1.25 ms |

| Swin | ~4.7 G | 10 s | 1.02 ms |

| ViT | ~17.5 G | 34 s | 2.88 ms |

| AST | ~17.5 G | 37 s | 2.94 ms |

| Time | Accuracy | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.957 |

| 2 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.957 |

| 3 | 0.963 | 0.955 | 0.955 |

| 4 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.957 |

| 5 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.955 |

| 6 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.957 |

| 7 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.956 |

| 8 | 0.959 | 0.951 | 0.951 |

| 9 | 0.961 | 0.955 | 0.957 |

| 10 | 0.960 | 0.953 | 0.953 |

| Mean | 0.9618 | 0.9538 | 0.9555 |

| Std | 0.14% | 0.11% | 0.19% |

| Model | Method | Accuracy | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swin | MFCC | 0.915 | 0.911 | 0.908 |

| Swin | CWT | 0.914 | 0.905 | 0.907 |

| Swin | Fusion | 0.939 | 0.937 | 0.935 |

| I-Swin | MFCC | 0.949 | 0.949 | 0.945 |

| I-Swin | CWT | 0.875 | 0.866 | 0.868 |

| I-Swin | Fusion | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.957 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, B. Railway Signal Relay Voiceprint Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Swin-Transformer and Fusion of Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3846. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233846

Liu Y, Chen L, Wang Z, Zhou S, Zhao B. Railway Signal Relay Voiceprint Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Swin-Transformer and Fusion of Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3846. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233846

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yi, Liang Chen, Zhen Wang, Shangmin Zhou, and Bobo Zhao. 2025. "Railway Signal Relay Voiceprint Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Swin-Transformer and Fusion of Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3846. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233846

APA StyleLiu, Y., Chen, L., Wang, Z., Zhou, S., & Zhao, B. (2025). Railway Signal Relay Voiceprint Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Swin-Transformer and Fusion of Gaussian-Laplacian Pyramid. Mathematics, 13(23), 3846. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233846