Event-Triggered Adaptive Control for Multi-Agent Systems Utilizing Historical Information

Abstract

1. Introduction

- For multi-agent systems, this paper proposes a novel distributed adaptive control scheme integrating command filters and historical information. This scheme not only avoids the explosion of complexity but also ensures the boundedness of closed-loop signals. Compared with existing studies, the proposed scheme indirectly incorporates historical information into the controller design process, providing a new approach for memory to guide the behavior of followers.

- Distinct from the ETC scheme presented in [22,23], this paper draws inspiration from the human brain’s ability to make decisions by leveraging memory and proposes a single-point historical triggering mechanism, which capitalizes on memory at a specific moment, and a moving window-based historical triggering mechanism, which incorporates memory over a time interval, where the maximum memory length is constrained by a dynamic parameter, to mitigate potential deviations induced by long-term memory. The proposed framework provides an alternative approach to adaptively designing ETC through historical information.

2. Problem Formulation

3. Controller Design and Theoretical Analysis

3.1. Event-Triggered Mechanism with Memory

3.2. Distributed Control Protocol

3.3. System Stability and Zeno Behavior Analysis

4. Simulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Meaning |

| N | Number of followers; is the agent index. |

| State of agent i; n is the system order. | |

| Output and continuous control input of agent i. | |

| Leader/reference trajectory. | |

| Stacked follower outputs. | |

| Output tracking error vector. | |

| Directed communication graph. | |

| Adjacency/weight matrix ( if ). | |

| In-degree matrix, . | |

| Laplacian matrix. | |

| Pinning (leader-coupling) gain matrix. | |

| First-layer consensus tracking error (neighbor differences + pinning). | |

| Stacked error satisfying . | |

| Auxiliary/history-based compensation signal at layer j. | |

| Compensated (filtered) error at layer j. | |

| Virtual control and its command-filtered version. | |

| k-th triggering instant of agent i. | |

| Applied/held input between events. | |

| Triggering measurement error. | |

| Trigger threshold coefficients. | |

| Dynamic triggering parameter (Cases 1–2). | |

| Memory limiter/weight (used in Case 2). | |

| RBF basis vector; M is the number of neurons. | |

| NN approximation error, bounded by . | |

| Adaptive parameter (minimal learning) at layer j. |

References

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Q.; Duan, Z. Optimal Distributed Leader-Following Consensus of Linear Multi-Agent Systems: A Dynamic Average Consensus-Based Approach. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2022, 69, 1208–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Lin, Z. Distributed Consensus Control of Multi-Agent Systems with Higher Order Agent Dynamics and Dynamically Changing Directed Interaction Topologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2016, 61, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Duan, Z.; Wang, J. Distributed Optimal Consensus Control Algorithm for Continuous-Time Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2020, 67, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kada, B.; Khalid, M.; Shaikh, M.S. Distributed Cooperative Control of Autonomous Multi-agent UAV Systems Using Smooth Control. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2020, 31, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Shu, Z.; Huang, T. Resilient Consensus Control of Heterogeneous Multi-UAV Systems with Leader of Unknown Input Against Byzantine Attacks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 5388–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Distributed Attitude Consensus of Spacecraft Formation Flying. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2013, 24, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfati-Saber, R.; Shamma, J.S. Consensus Filters for Sensor Networks and Distributed Sensor Fusion. In Proceedings of the 44th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Seville, Spain, 15 December 2005; pp. 6698–6703. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W. Distributed Consensus Filtering in Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B 2009, 39, 1568–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.; Marquez, H.J. Observer-Based Event-Triggered Consensus Control of Multi-Agent Systems with Time-Varying Communication Delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 6336–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhang, G. Dynamic Event-Triggered-Based Single-Network ADP Optimal Tracking Control for the Unknown Nonlinear System with Constrained Input. Neurocomputing 2023, 518, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H. Integral-Based Memory Event-Triggered Controller Design for Uncertain Neural Networks with Control Input Missing. Mathematics 2025, 13, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.M.; Rad, A.B. Identification of Nonlinear Systems with Unknown Time Delay Based on Time-Delay Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2007, 18, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, C.L. Output-Feedback Adaptive Neural Control for Stochastic Nonlinear Time-Varying Delay Systems with Unknown Control Directions. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 1188–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Tao, J.; Li, M.; Su, C.; Lu, R. Adaptive Neural Network Tracking Control for Unknown High-Order Nonlinear Systems: A Constructive Approximation Set Based Approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Ren, S.; Peng, B. Performance-Barrier-Based Event-Triggered Leader–Follower Consensus Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. Neurocomputing 2025, 657, 131664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. Cooperative Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems Based on Event-Triggered Scheme. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2021, 68, 1977–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Yoo, S.J. Neural-Network-Based Distributed Asynchronous Event-Triggered Consensus Tracking of a Class of Uncertain Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 2965–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y. Neural Network Event-Triggered Formation Fault-Tolerant Control for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems With Actuator Faults. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 7571–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, B. Neural Network-Based Distributed Cooperative Learning Control for Multiagent Systems via Event-Triggered Communication. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Luo, R.; Hu, J.; Shi, K.; Ghosh, B.K. Distributed Optimal Tracking Control of Discrete-Time Multiagent Systems via Event-Triggered Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 2022, 69, 3689–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.A.; Zhang, G.J.; Niu, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.M. Event-Triggered-Based Consensus Neural Network Tracking Control for Nonlinear Pure-Feedback Multiagent Systems with Delayed Full-State Constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 7390–7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Dynamic Memory Event-triggered Adaptive Control for a Class of Strict-Feedback Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 3470–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Tong, S. Event-Based Finite-Time Control for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems with Asymptotic Tracking. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2023, 68, 3790–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X. Command Filter Adaptive Asymptotic Tracking of Uncertain Nonlinear Systems with Time-Varying Parameters and Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Contr. 2022, 67, 2973–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Cao, Y. Distributed Coordination of Multi-Agent Networks: Emergent Problems, Models, and Issues; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.X.; Yang, G.H. Adaptive Asymptotic Tracking Control of Uncertain Nonlinear Systems with Input Quantization and Actuatorfaults. Automatica 2016, 72, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Huang, L. Generalized Lyapunov Approach for Functional Differential Inclusions. Automatica 2020, 113, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Huang, T. Neural-Network-Based Event-Triggered Adaptive Control of Nonaffine Nonlinear Multiagent Systems With Dynamic Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 2239–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davó, M.A.; Prieur, C.; Fiacchini, M. Stability Analysis of Output Feedback Control Systems with a Memory-Based Event-Triggering Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Autom. Contr. 2017, 62, 6625–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A. Dynamic Triggering Mechanisms for Event-Triggered Control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Contr. 2015, 60, 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yu, J.; Lin, C.; Ma, Y. Adaptive Neural Consensus Tracking for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems using Finite-Time Command Filtered Backstepping. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 48, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Xing, L.; Zhong, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhong, W. Adaptive Fixed-Time Fuzzy Containment Control for Uncertain Nonlinear Multiagent Systems with Unmeasurable States. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) Limiter Initial Value (Case 2) | ||||||

| 3.00 | 4967 | 0.001000 | 0.080583 | |||

| 6.00 | 5058 | 0.001000 | 0.079058 | |||

| 9.00 | 4999 | 0.001000 | 0.080030 | |||

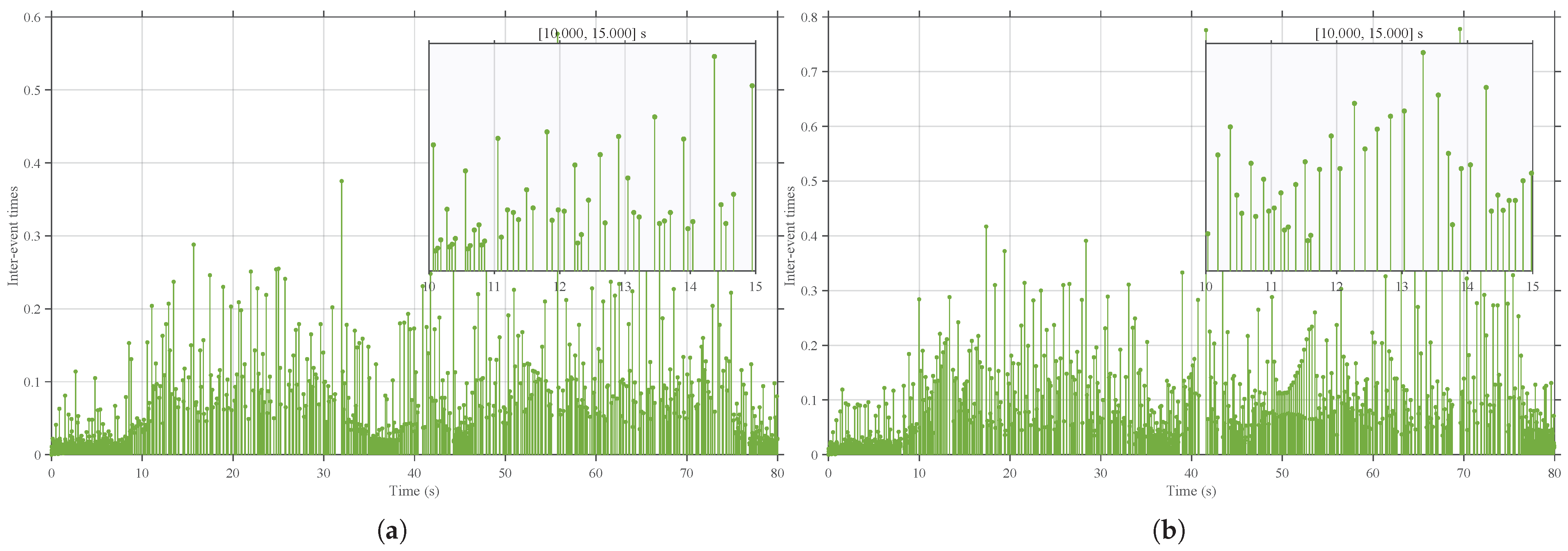

| (2) Memory Length h | ||||||

| Case 1 (Case1) | Case 2 (Case2) | |||||

| 0.050 | 5692 | 0.001000 | 0.070296 | 4931 | 0.001000 | 0.081162 |

| 0.100 | 5611 | 0.001000 | 0.071302 | 5058 | 0.001000 | 0.079058 |

| 0.200 | 5545 | 0.001000 | 0.072063 | 4902 | 0.001000 | 0.081610 |

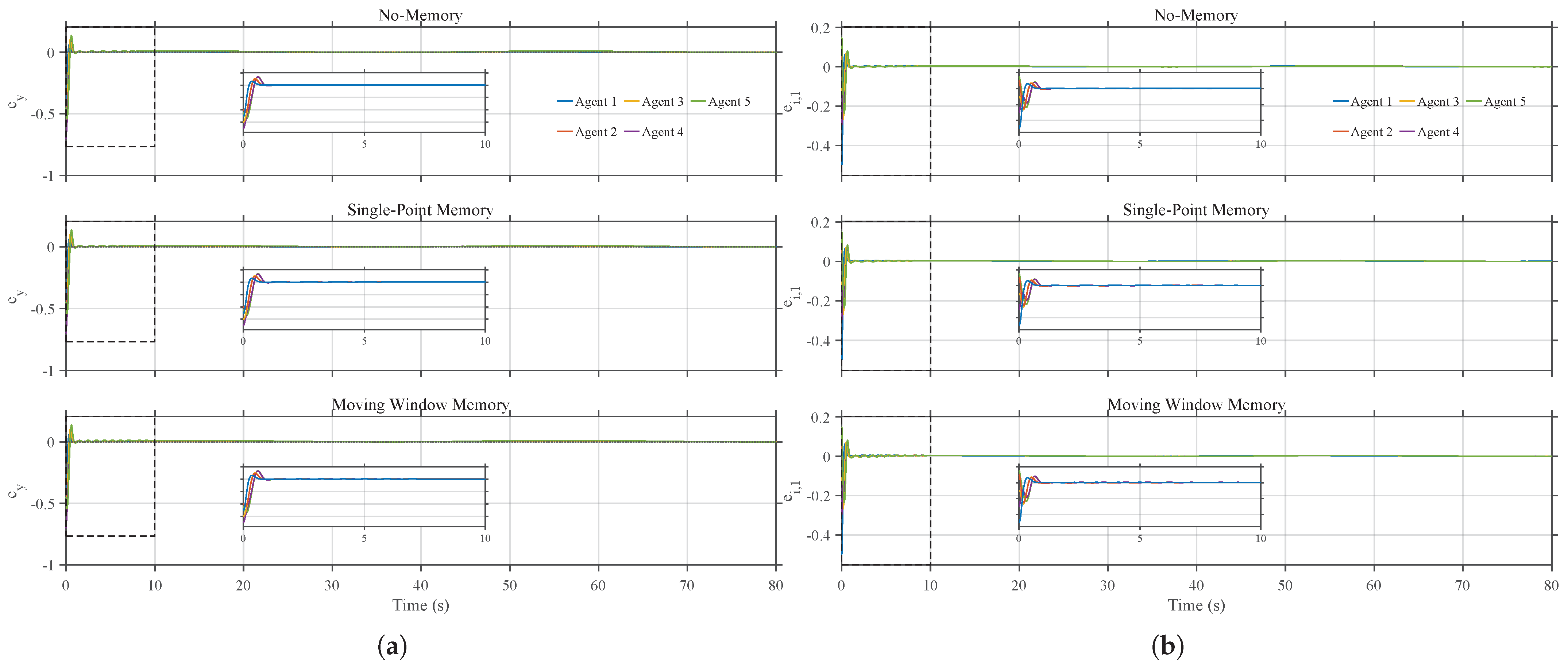

| Overall Triggering-Time Statistics | |||||

| Method | |||||

| No memory | 7194 | 0.001000 | 0.055628 | ||

| Case 1 (single-point memory) | 5611 | 0.001000 | 0.071302 | ||

| Case 2 (moving window memory) | 5058 | 0.001000 | 0.079058 | ||

| Per-Agent Triggering Counts and Savings | |||||

| Agenti | (No-Memory) | (Case1) | (Case2) | Saving (Case1) | Saving (Case2) |

| 1 | 964 | 764 | 681 | 20.75% | 29.36% |

| 2 | 1401 | 1116 | 976 | 20.34% | 30.34% |

| 3 | 1319 | 1056 | 908 | 19.94% | 31.16% |

| 4 | 1732 | 1342 | 1255 | 22.51% | 27.54% |

| 5 | 1778 | 1333 | 1238 | 25.03% | 30.37% |

| Total | 7194 | 5611 | 5058 | 22.0% | 29.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Fan, Q.-Y. Event-Triggered Adaptive Control for Multi-Agent Systems Utilizing Historical Information. Mathematics 2026, 14, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020261

Liu X, Wang H, Fan Q-Y. Event-Triggered Adaptive Control for Multi-Agent Systems Utilizing Historical Information. Mathematics. 2026; 14(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020261

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinglan, Hongmei Wang, and Quan-Yong Fan. 2026. "Event-Triggered Adaptive Control for Multi-Agent Systems Utilizing Historical Information" Mathematics 14, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020261

APA StyleLiu, X., Wang, H., & Fan, Q.-Y. (2026). Event-Triggered Adaptive Control for Multi-Agent Systems Utilizing Historical Information. Mathematics, 14(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020261