Cooperation Strategies of Sharing Platform and Manufacturers Considering Value-Added Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Shared Manufacturing

2.2. Sharing Platform and VAS

2.3. Cooperation Strategies in Supply Chain

3. Problem Description and Assumptions

4. Model and Analysis

4.1. Model N

4.2. Model CS

4.3. Model RS

4.4. Analysis of the Equilibrium Results

4.4.1. Main Parameters Effects on the Equilibrium Results

4.4.2. Comparative Analysis

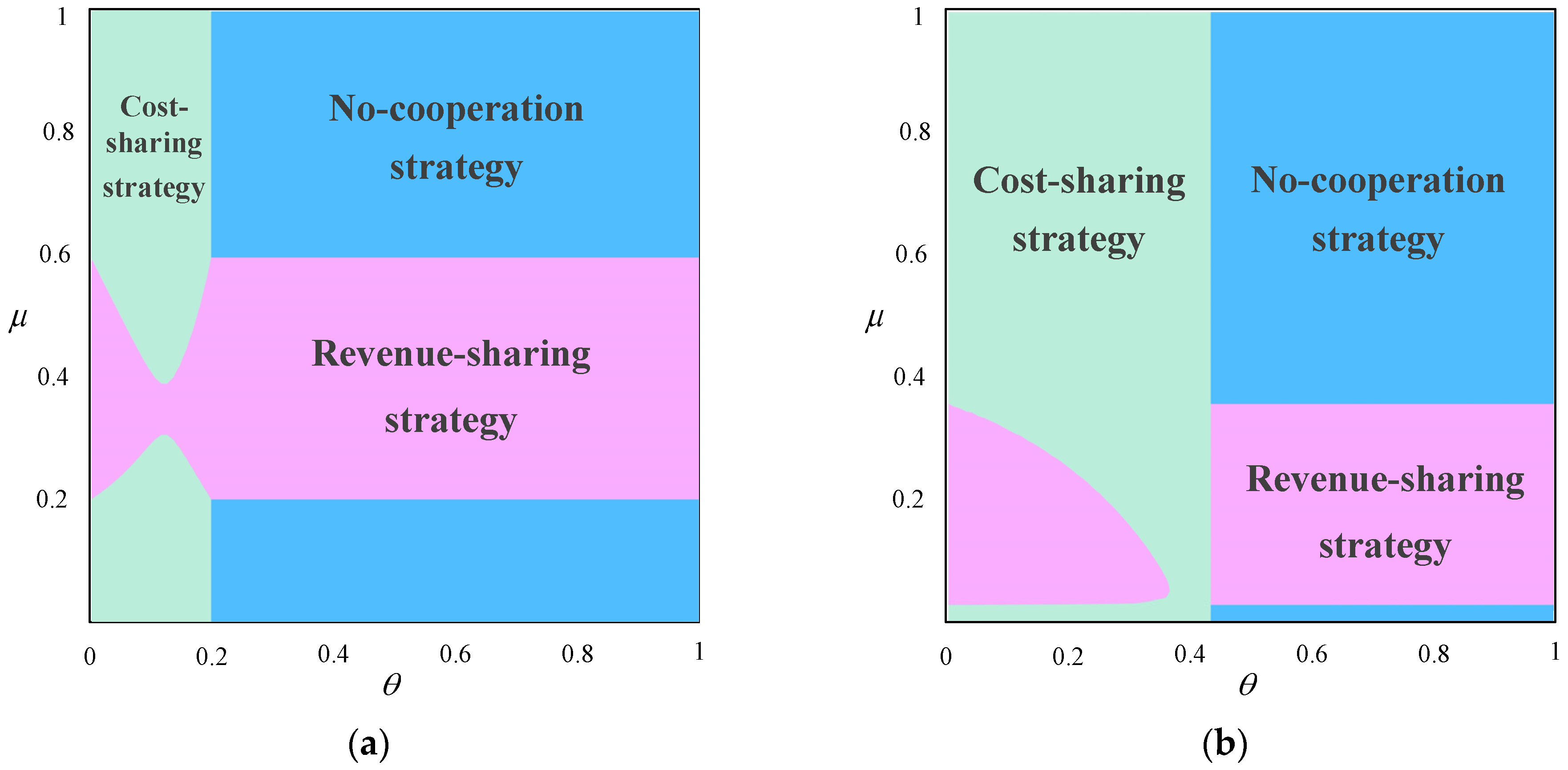

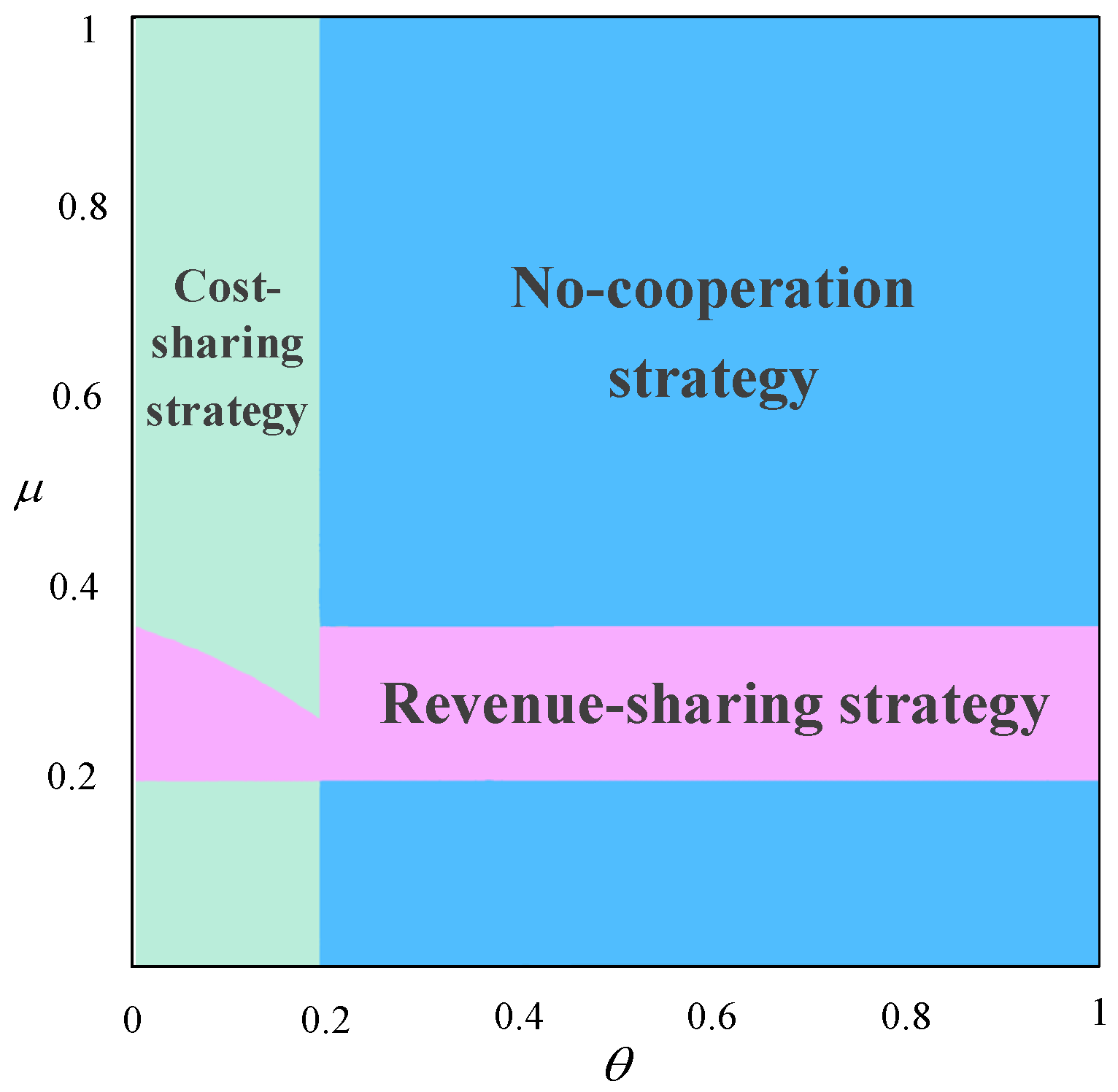

4.4.3. Selection of Cooperation Strategy

5. Numerical Analysis

5.1. The Impact of VAS Cost Coefficient

5.2. The Impact of Sensitivity of Demand to the VAS Level

5.3. The Impact of Market Potential

5.4. The Impact of Manufacturer’s Unit Production Cost

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Proof of the Equilibrium Outcomes

Appendix A.2. Proof of Propositions

Appendix B

| Variable | Optimal Solutions | Variable | Optimal Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Optimal Solutions | Variable | Optimal Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Optimal Solutions |

|---|---|

References

- Xiang, W.; Yu, K.; Han, F.; Fang, L.; He, D.; Han, Q.-L. Advanced manufacturing in industry 5.0: A survey of key enabling technologies and future trends. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2023, 20, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Yu, S.; Sang, Z.; Yang, C.; Jiang, X. Shared manufacturing in the sharing economy: Concept, definition and service operations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-Z.; Feng, G.; Yi, Z.; Guo, X. Service-oriented manufacturing: A literature review and future research directions. Front. Eng. Manag. 2022, 9, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, C.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, J.; Adeleke, I.B. An evolutionary game approach for manufacturing service allocation management in cloud manufacturing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 133, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wu, X. Capacity sharing between competitors. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 3554–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, Z. Capacity sharing, product differentiation and welfare. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-Q.; Hu, Z.-H.; Ma, H.-W.; Liu, F. Dynamic cooperative value-added service strategies of the smart manufacturing platform considering the network effect and altruism preference. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 184, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, J.; Gu, X. Research on sharing manufacturing in Chinese manufacturing industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, J.; Buxmann, P. Assessing the value of interorganizational systems to support business transactions. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2000, 4, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.-M.; Ho, C.-F.; Wu, W.-H. The performance impact of implementing web-based e-procurement systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 5397–5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Datta, P.P.; Fernandes, K.J.; Xiong, Y. Optimal pricing strategies for manufacturing-as-a service platforms to ensure business sustainability. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 234, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Xie, J.; Xia, Y.; Wei, L.; Liang, L. Getting more third-party participants on board: Optimal pricing and investment decisions in competitive platform ecosystems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Tan, C.; Wu, D.D.; Zhao, C. Strategies choice for blockchain construction and coordination in vaccine supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Anderson, E.G., Jr.; Parker, G.G. Platform pricing and investment to drive third-party value creation in two-sided networks. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Xia, L. Revenue sharing contracts for horizontal capacity sharing under competition. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Energy storage capacity optimization of non-grid-connected wind-hydrogen systems: From the perspective of hydrogen production features. Power Eng. Eng. Thermophys. 2022, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jiang, X.; Yu, S.; Yang, C. Blockchain-based shared manufacturing in support of cyber physical systems: Concept, framework, and operation. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2020, 64, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M.; Cadavid, M.; Kenley, R.; Deshmukh, A. Reference architectures for smart manufacturing: A critical review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 49, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y. Economic implications of equipment sharing under cloud manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 254, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.V.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L. Scheduling in cloud manufacturing: State-of-the-art and research challenges. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4854–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Sun, F.; Jiang, Y. Online hierarchical parallel machine scheduling in shared manfacturing to minimize the total completion time. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2022, 74, 2432–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cui, Z.; Li, H.; Jia, R. Optimization and coordination of the fresh agricultural product supply chain considering the freshness-keeping effort and inforation sharing. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, C.; Liu, J. Shared manufacturing in a differentiated duopoly with capacity constraints. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 8107–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Bo, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Effects of different resource-sharing strategies in cloud manufacturing: A Stackelberg game-based approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, P. Capacity sharing between competing manufacturers: A collective good or a detrimental effect? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 268, 109107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. Capacity sharing with different oligopolistic competition and government regulation in a supply chain. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 41, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Shi, J. Capacity sharing for ride-sourcing platforms under competition. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 182, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charro, A.; Schaefer, D. Cloud Manufacturing as a new type of Product-Service System. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 31, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Lieberman, M.; Leiblein, M.; Wei, L.Q.; Wang, Y. The distinctive domain of the sharing economy: Definitions, value creation, and implications for research. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 927–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Liu, H.; Wei, C.; Zhang, C. Common engines of cloud manufacturing service platform for SMEs. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 73, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thitimajshima, W.; Esichaikul, V.; Krairit, D. A framework to identify factors affecting the performance of third-party B2B e-marketplaces: A seller’s perspective. Electron. Mark. 2018, 28, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Han, H.; Shang, J.; Hao, J. Decisions and coordination in a capacity sharing supply chain under fixed and quality-based transaction fee strategies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 150, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jia, L.; Hu, X. Operation decision model in a platform ecosystem for car-sharing service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 59, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, R.; Zhang, X.; Dan, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Bilateral value-added service investment in platform competition with cross-side network effects under multihoming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 304, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Dan, B. Match of the cross-period capacity on the third-party shared manufacturing platform with demand delay. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240, 122479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Wei, W.; Xie, D. Pricing decisions for service platform with provider’s threshold participating quantity, value-added service and matching ability. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 122, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocco, R.; Perego, A.; Perotti, S. B2b eMarketplaces: A classification framework to analyse business models and critical success factors. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 1117–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Bhaskaran, S.; Mukherjee, R. An analysis of search and authentication strategies for online matching platforms. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 2412–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerchak, Y.; Wang, Y. Revenue-sharing vs. wholesale-price contracts in assembly systems with random demand. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2004, 13, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Lariviere, M.A. Supply chain coordination with revenue-sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kouvelis, P.; Matsuo, H. Horizontal capacity coordination for risk management and flexibility: Pay ex ante or commit a fraction of ex post demand? Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, F.; Li, S.X.; Huang, Z.; Ashley, A. Coordination and performance analysis for a three-echelon supply chain with a revenue sharing contract. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roels, G.; Tang, C.S. Win-win capacity allocation contracts in coproduction and codistribution alliances. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 861–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Gong, B.; Li, B. Cooperation strategy of technology licensing based on evolutionary game. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Xu, M. Dynamic cooperation strategies of the closed-loop supply chain involving the internet service platform. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kouvelis, P. On co-opetitive supply partnerships with end-product rivals: Information asymmetry, dual sourcing and supply market efficiency. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, J.; Liu, J. Capacity sharing strategy with sustainable revenue-sharing contracts. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J. Pricing and replenishment decisions for seasonal and nonseasonal products in a shared supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 233, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Fan, Z.-P.; Sun, M. B2C car-sharing services: Sharing mode selection and value-added service investment. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 165, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; He, X. Contract and product quality in platform selling. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 272, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Ma, J.; Goh, M. Supply chain coordination in the presence of uncertain yield and demand. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 4342–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Competing Manufacturers | Sharing Platform | Value- Added Service (VAS) | Cooperation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qin et al. (2020) [15] | Bertrand | none | none | revenue-sharing |

| Sun et al. (2021) [48] | Bertrand | Yes | none | none |

| Zhang et al. (2022) [16] | none | Yes | endogenous | none |

| Guo et al. (2022) [49] | none | Yes | exogenous | sharing mode selection |

| Hu et al. (2022) [19] | none | Yes | none | none |

| Cai et al. (2023) [33] | none | Yes | exogenous | revenue-sharing |

| Cao et al. (2023) [24] | Cournot | Yes | none | resource sharing |

| Chen et al. (2023) [23] | Cournot | none | none | none |

| Chen et al. (2024) [25] | Cournot | none | none | cost-sharing |

| This study | Bertrand | Yes | endogenous | sharing mode selection |

| Notation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Selling price of manufacturer in Model (decision variable) | |

| Market demand of manufacturer in Model | |

| Market potential | |

| Manufacturer’s unit production cost, | |

| Competition intensity, | |

| Cost-sharing ratio in Model CS, | |

| Revenue-sharing rate in Model RS, | |

| Commission fee in Model (decision variable) | |

| VAS level of the sharing platform in Model (decision variable) | |

| VAS cost coefficient, | |

| Sensitivity of demand to the VAS level, | |

| Profit of manufacturer in Model | |

| Profit of the sharing platform in Model | |

| Profit of the supply chain in Model | |

| Index for the manufacturers, | |

| Index for the models, |

| Notation | Variables | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Market potential | 100 | |

| Manufacturer’s unit production cost | 15 | |

| Competition intensity | 0.5 | |

| VAS cost coefficient | 0.6 | |

| Sensitivity of demand to the VAS level | 0.7 | |

| Cost-sharing ratio in Model CS | 0.1 | |

| Revenue-sharing rate in Model RS | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, H.; Yan, J.; Shu, T.; Li, J.; Wang, S. Cooperation Strategies of Sharing Platform and Manufacturers Considering Value-Added Services. Mathematics 2026, 14, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020252

Zeng H, Yan J, Shu T, Li J, Wang S. Cooperation Strategies of Sharing Platform and Manufacturers Considering Value-Added Services. Mathematics. 2026; 14(2):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020252

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Huabao, Jin Yan, Tong Shu, Jinhong Li, and Shouyang Wang. 2026. "Cooperation Strategies of Sharing Platform and Manufacturers Considering Value-Added Services" Mathematics 14, no. 2: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020252

APA StyleZeng, H., Yan, J., Shu, T., Li, J., & Wang, S. (2026). Cooperation Strategies of Sharing Platform and Manufacturers Considering Value-Added Services. Mathematics, 14(2), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14020252