1. Introduction

In recent years, the meshfree smoothed point interpolation method (SPIM) has undergone rapid development [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Compared with the finite element method (FEM), the SPIM has a more accurate stiffness and is not sensitive to mesh distortion [

9,

10], which can overcome the “overly-stiff” phenomenon and mesh dependence of the FEM. However, the usage frequency of SPIM is far less than that of the FEM. One of the important factors is that the SPIM does not have optional commercial software and open-source programs like the FEM, which seriously limits the application of the SPIM. Thus, developing an effective SPIM simulation program can help to expand the application scope of the SPIM in solving engineering problems.

To this end, an effective simulation program based on the face-based SPIM [

11,

12] was developed, which has been applied to solve geomechanical problems (e.g., the deformation of rock and soil masses) [

13,

14]. However, when simulating the deformation of rock and soil masses, there are still challenges. (1) Compared with metal materials, the geometric size of the rock and soil masses is usually large, and the calculation model usually needs more nodes and elements, which will cause serious calculation efficiency problems and memory bottlenecks. To solve these problems, the research team has proposed an efficient stiffness matrix compression storage strategy and introduced the PARDISO solution library to solve the system equations for the face-based SPIM, which enhanced the calculation efficiency and reduced the memory bottleneck [

13]. (2) The deformation of rock and soil masses may be highly nonlinear, which will affect the convergence and stability of the simulation program, especially in a critical state. To enhance the convergence, the research team discussed the performance of the Atiken method [

15] in accelerating convergence for SPIM [

13], but the convergence still needs to be improved. Thus, to enhance the performance of the simulation program, several effective strategies are proposed to improve the calculation efficiency, convergence, and stability.

The first issue we are concerned about is the convergence and stability of the simulation program. Since the face-based SPIM belongs to the implicit method, the incremental method and the Newton–Rapson iterative method are usually used to solve the governing equations [

16]. Generally, the iteration can be divided into a local iteration and global iteration, where the local iteration is the stress integration algorithm, and the global iteration is the balance between internal and external forces. For the stress integration algorithm, its main idea is to solve the stress increment according to the given strain increment, which requires an iterative process to achieve plastic correction [

17]. However, the stress integration algorithm may cause a convergence problem, even for simple ideal elastic–plastic models, which will cause nonconvergence in regions with high curvature of the yield surface [

18]. For global iteration, its convergence is very sensitive to the size of the increment step, especially in a critical state. For an unknown calculation model, setting appropriate incremental steps can improve the stability of the simulation program. To improve the convergence and stability of the simulation program, in this paper, effective accelerated convergence strategies are designed based on the classical line search algorithm and adaptive sub-step method. Furthermore, this paper improves these methods in terms of the selection of local and global iteration step sizes [

19].

Another issue we are concerned about is the computational efficiency of the simulation program. To improve the calculation efficiency, an effective strategy is to parallelize the program. Taking the FEM as an example, researchers have proposed parallel FEM based on the Central Processing Unit (CPU) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] and the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) [

26,

27,

28,

29] and achieved satisfactory results. For example, Oh and Hong [

22] parallelized the FEM code using the Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) library and achieved a satisfactory acceleration effect. For the simulation of a 3D cube under dynamic load, when the number of elements reaches 1,000,000, the calculation efficiency of the parallelized program using 24 cores is 12 times faster than the original serial code. For the FEM, Cecka [

27] established and analyzed various methods for assembling and solving sparse linear systems of the FEM using Computing Unified Device Architecture (CUDA). The results show that GPU code using single precision can achieve a speedup ratio of 30 or more compared to a single-core CPU using double precision. Compared to GPU parallelization, CPU parallelization is easier to implement [

30]. At present, research on CPU parallelization for SPIM has not been seen yet. Thus, this paper considers the OpenMP parallelization analysis and design of the SPIM program for the first time, mainly including feasibility analysis, parallelization implementation, and performance testing.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 gives a brief introduction to the face-based SPIM.

Section 3 introduces several accelerated convergence strategies.

Section 4 presents the OpenMP parallelization implementation of the SPIM.

Section 5 provides the numerical test results.

Section 6 includes the discussion and future work.

Section 7 presents the conclusions.

2. Brief Introduction to the SPIM

Based on the generalized smoothing Galerkin weak form [

10], the governing equations of the SPIM can be expressed as follows:

where

is the smoothing strain field,

is the standard displacement field obtained by the point interpolation method (PIM) [

31],

is the material matrix,

is the body force vector, and

is the surface force vector. In fact, the governing equations of the SPIM are similar to those of the FEM. The difference is that the SPIM uses a smoothing strain field

obtained based on the smoothing domain, and the smoothing domain can be constructed based on the background mesh of the FEM. For commonly used tetrahedral meshes, the smoothing domain can be formed based on each triangular facet, and the smoothing domain can be obtained by connecting the three nodes of each triangular facet with the centroids of the tetrahedra adjacent to each triangular facet. When the triangular facet lies at the boundary of the calculation model, the smoothing domain is tetrahedral; otherwise, the smoothing domain is hexahedral [

32]. The expression of the smoothing strain field

is given as follows:

where

is the standard strain field obtained by the PIM,

is the volume of each smoothing domain

bounded by

,

represents the differential operator, and

represents the smoothing operator.

Furthermore, the discretized form of the smoothing strain field

can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the smoothing strain matrix,

represents the displacement vector,

is the number of interpolation nodes associated with the smoothing domain, and the details of the node selection schemes can be seen in Reference [

33]. In this paper, the T4 node selection scheme is used to search interpolation nodes. Furthermore, the expression of

is given as follows:

and the discrete formula of the

is given as follows:

where

is the number of boundary triangular facets of each smoothing domain. For the inner smoothing domain,

is 6; otherwise,

is 4.

is the number of Gauss points of each boundary triangular facet, and

is 1 in this paper.

is the weight,

is the shape function, and

is the unit outer normal vector.

By substituting the standard displacement field

and smoothing strain

into Equation (

1) and activating the variational operation, the discretized governing equation can be expressed as follows:

where

and

represent the shape function vector [

31].

3. Accelerated Convergence Strategies

As stated in the Introduction, the Newton–Raphson method is used to conduct the local iteration and global iteration. However, the Newton–Raphson method converges only when the initial estimate is within the convergence radius. Moreover, the convergence is very sensitive to the size of the increment step for both local and global iterations. To enhance the convergence of both local and global iterations, efficient accelerated strategies are proposed by incorporating the line search method [

34] and adaptive sub-step method [

19].

3.1. Local Iteration

3.1.1. Stress Integration Algorithm

This paper uses the Closest Point Projection Method (CPPM) to conduct the stress integration [

18], which belongs to the completely implicit method and has a higher precision. The core idea of the CPPM is elastic prediction and plastic correction, see

Figure 1. If the elastic trial stress does not exceed the yield surface, the stress is updated directly without correction. If the elastic trial stress exceeds the yield surface, it needs to be corrected to the yield surface. Usually, the Newton–Raphson iterative method is used to conduct the plastic correction, and its iterative process is listed as follows:

(1) Set initial value: Before starting the iteration, the initial stress value is the initial elastic trial stress

, and the plastic parameter

is set to 0. Then, we have

In this paper, the path independent strategy is used to update the strain increment

, which is updated based on the convergent value of the previous increment step. The path independent strategy can describe the strain path more reasonably and avoid the pseudo-unloading phenomenon [

35].

(2) Determine convergence or not:

If

, it converges and stops; otherwise, it continues to step (3).

(3) Calculate the stress residual

, plastic parameter increment

, and stress increments

:

where

,

is the new elastic trial stress,

is the unit matrix, and

and

represent the first derivative of the yield function and the potential function with respect to stress, respectively.

(4) Update stress

, plastic parameter

:

and then proceed to step (2).

When the path independent strategy and the closest point projection method are used for stress integration, the consistent tangential stiffness matrix

needs to be derived, which represents the rate of change of stress increment to strain increment and can be expressed as follows:

where

Moreover, the consistent tangential stiffness matrix can keep the asymptotic quadratic convergence rate of the Newton–Raphson method and also can avoid the pseudo-unloading caused by continuum tangential stiffness matrix.

However, the iterative process encounters a convergence problem; even for the ideal elastoplastic model, convergence problems may occur in high curvature regions of the yield surface [

18]. To enhance the convergence of plastic correction, this paper employs the line search method and adaptive sub-step method.

3.1.2. Line Search Method

Only when the initial estimate is within the radius of convergence, the Newton–Raphson method shows good convergence. Moreover, the step size of the iteration is fixed, and the function value cannot be guaranteed to decline steadily. To ensure the function value decreases steadily, the line search method can be used to search for a proper step size that makes the function value decrease. In the line search method, the determination of step size can be divided into the accurate method and the inaccurate method [

36,

37]. The accurate method needs to search for a global optimal step size, which is very time-consuming. Thus, the inaccurate method is generally adopted, and the condition can be satisfied once the step size satisfies the function value decreases. In this paper, the simple backtracking algorithm is used, which needs to meet the following conditions:

where

is the objective function,

is the descent direction,

is the step size, and

c is a dimensionless parameter and is usually set to

. From

Figure 2, if the step size

is set within

and

, the function value will decrease.

In the CPPM, the stress residual

is used to determine whether the plastic correction is completed and it can be expressed as follows:

To apply the line search method [

34], the Euclidean norm of the stress residual

is chosen as the objective function. Moreover, the step size of the iteration can be controlled by only modifying the parameter

using the line search parameter

:

Usually, the initial value of the line search parameter

is set to 1, which indicates that the Newton–Raphson method is used for iteration first. Assume that the function value of the iteration

is greater than that of the iteration

k, i.e.,

where

is the Euclidean norm operation,

is the line search parameter at the iteration

k, and

is the fixed parameter; in this paper,

.

If Equation (

18) is satisfied, the results of the iteration

are discarded, and the line search method is activated by replacing

using

, where parameter

is the reduction factor and usually less than 1. Then, the iteration

is restarted using a smaller step size. If Equation (

18) is not satisfied, the proper step size is determined, and the line search parameter is kept unchanged in the following iterations. If Equation (

18) is satisfied again, the line search parameter continues to be reduced until convergence is achieved. Usually, the number of searches is limited, and when the number of searches exceeds the maximum number, the line search fails; in this paper, the maximum number is set to 5.

In this paper, another case is considered: the convergence of the plastic correction can be completed by using the Newton–Raphson method, but the convergence rate is very slow. To solve this problem, when the Newton–Raphson method does not converge after 10 iterations, the line search parameter is enlarged for the next iteration; in this paper, the enlargement factor is set to 2.

3.1.3. Adaptive Sub-Step Method

When the line search method fails, this paper further adopts an adaptive sub-step strategy to ensure convergence. In the adaptive sub-step strategy, the strain increment is divided into multiple parts, and the stress update is performed in each strain increment. In this paper, the strain increment

is divided into

m uniform parts:

In this paper, the parameter is constant and is equal to , the parameter m is dynamically adjusted, and its initial value is 1. When the line search fails, the current result is discarded, and the parameter m is enlarged, where the enlargement factor is 2. Then, the plastic correction is restarted, if convergence fails, the parameter m is continued to enlarge until convergence.

Assume that the stress before the update is

, and the stress after the update is

. In the adaptive sub-step strategy, the process of stress update is expressed as follows:

For each sub-step, the plastic correction is conducted using the Newton–Rapson method and the line search method.

For the adaptive sub-step strategy, the consistent tangent stiffness matrix in Equation (

14) is not appropriate. Thus, a consistent tangential stiffness matrix conforming to the adaptive sub-step strategy is adopted [

19]. For each sub-step

k, the nonlinear equations can be expressed as follows:

where

For example, when

,

, Equation (

21) can be expressed as follows:

which is consistent with Equation (

14).

3.2. Global Iteration

For global iteration, when the incremental step size is large, the simulation program may not converge, especially in the critical state, and it is very sensitive to the size of the incremental step. Thus, selecting an appropriate increment step size can improve the convergence and stability of the simulation program. In ABAQUS, the adaptive sub-step method in the global iteration is designed as follows: if a sub-step can converge within a reasonable number of iterations, the incremental step size remains unchanged. If two consecutive sub-steps converge with a small number of iterations (≤4), the subsequent step size of each sub-step is increased by 50%; if a sub-step cannot converge after several iterations (≥16), 25% of the current step size is taken as the new step size. If the incremental step size is less than the specified value, the analysis program will not converge.

In this paper, a new adaptive sub-step method for global iteration is designed and can be expressed as follows:

(1) In the elastic stage, there is no convergence problem, which allows a larger incremental step size. To complete the elastic stage quickly, the initial step size can be determined by elastic trial calculation. The purpose is to make the initial step size as large as possible, and the model is still in the elastic phase. First, the trial step size R0 is initialized to 0.1. Second, for each smoothing domain, the stress is calculated using the elastic model. Once the stress of any smoothing domain exceeds the yield surface, the calculation model is judged in the plastic stage, and the initial step size R1 is set to R0. Otherwise, if the model is still in the elastic stage, then, we enlarge the R0 by adding 0.1 until the model is in the plastic phase.

(2) When determining the initial step size R1, the subsequent incremental step size R2 remains unchanged as long as the number of iterations within the incremental step is less than N.

(3) When the number of iterations within the incremental step is higher than N, it can be judged that the incremental step does not converge, and the N is set to 20 in this paper. Then, the new incremental step size is set to 50% of R2, and we restart the iteration. If the incremental step size is reduced 5 times and still cannot converge, it can be judged that the analysis program cannot converge.

Compared with the ABAQUS, the operation of enlarging the incremental step size is not considered in the SPIM simulation program. The reason is that the stress may diverge from the yield surface when the incremental step size is large, which will increase the time of stress correction. Moreover, the number of iterations cannot be used to judge the nonlinearity degree; thus, it is not proper to enlarge the incremental step size in the plastic stage. Once the next incremental step cannot converge, it needs to be recalculated, which affects the calculation efficiency. Another change is that the calculation time of the elastic stage is effectively reduced by the elastic trial calculation.

4. OpenMP Parallel Design

The OpenMP is a parallel computing programming model, which can easily transform serial code into parallel code [

38]. The OpenMP works as follows: (1) Developers use OpenMP instructions to mark parallel regions. For example, the most commonly-used instruction is “#pragma omp parallel for”, which can be used before the

for loop. (2) The compiler analyzes these instructions and generates multi-thread parallel code. (3) The computer system is responsible for creating and managing threads and distributing the workload to different threads when running the program. (4) In parallel regions, multiple threads execute code at the same time and share variables in memory. However, when using the OpenMP, data competition and data dependence need to be avoided. For example, two threads updating a shared variable at the same time is not allowed. Thus, before parallelizing the SPIM simulation program, it is necessary to determine whether the main modules of the program can be parallelized, that is, whether the main module has data competition and data dependence.

The flowchart of the SPIM simulation program is illustrated as follows; see

Figure 3. The SPIM program mainly includes the following modules: constructing the smoothing domain, assembling the system stiffness matrix, imposing the boundary conditions, solving the system equations, and solving the stress and strain. In the following part, whether the main modules of SPIM are suitable for parallelization will be analyzed.

(1) Constructing the smoothing domain. The smoothing domain of the face-based SPIM can be constructed as follows: First, the centroid of each tetrahedron is determined; then, a loop for all edges of each tetrahedron is conducted, and the two nodes of each edge and the centroid of the tetrahedron can form a new triangular facet. Then, according to the topology between the edge and the face, the new triangular facet is stored as a boundary facet of the smoothing domain of the original face connected to the edge, where the original face is the triangular facet of the tetrahedron and not the newly generated triangular facet. Finally, after the loop is completed for all tetrahedrons, the loop continues for the triangular facets on the boundary surface, and each boundary triangular facet is stored as part of the smoothing domain of the boundary triangular facet.

As can be seen from the above, there is data competition when constructing the smoothing domain, and the reasons are as follows. The inner smoothing domain is composed of two adjacent tetrahedral elements. If the two tetrahedral elements are controlled by two different threads, there will be array access conflicts when storing the new triangular facet as the boundary surface of the smoothing domain. Moreover, designing adjacent tetrahedral elements to be controlled by the same thread is difficult. Thus, constructing the smoothing domain is not suitable for parallelization. To enhance the efficiency of constructing the smoothing domain, the effective algorithm is adopted in the simulation program [

32], which can effectively reduce the complexity of the algorithm.

(2) Assembling the system stiffness matrix. This part mainly includes calculating the sub-stiffness matrix of each smoothing domain and assembling the sub-stiffness matrix into the system stiffness matrix, and its concrete steps are as follows. First, a loop for all smoothing domains is conducted; then, the smoothing strain matrix of each smoothing domain is calculated. Then, the sub-stiffness matrix is calculated using Equations (

4) and (

5); finally, the sub-stiffness matrix is assembled into the system stiffness matrix. More details about assembling the system stiffness matrix can be seen in Reference [

13].

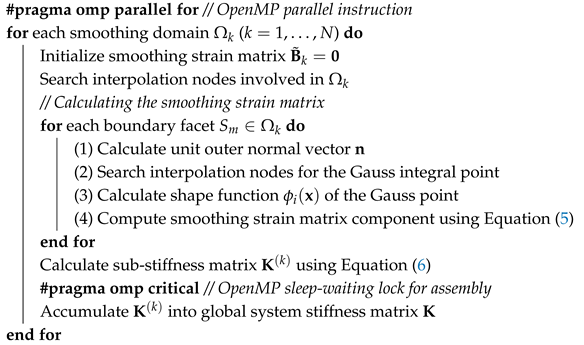

Since each smoothing domain is independent, the smoothing strain matrix and sub-stiffness matrix can be calculated using the OpenMP parallel method. However, when assembling the system stiffness matrix A, any two smoothing domains controlled by different threads may have the same node index, which will lead to array access conflicts when performing accumulation operations. However, considering that assembling the system stiffness matrix will occupy a lot of solving time, the parallel design for this region is still conducted. To avoid data competition, the sleep-waiting lock operation is adopted; see Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of assembling the system stiffness matrix using the OpenMP instruction |

![Mathematics 14 00007 i001 Mathematics 14 00007 i001]() |

(3) Imposing boundary conditions. To restrict rigid body motions, displacement boundary conditions must be imposed. Fortunately, the shape function of the SPIM has the property of the Kronecker function, and its displacement boundary conditions can be imposed as easily as the FEM. In this paper, the penalty function method is adopted to impose boundary conditions [

39]. The penalty function method only needs to modify diagonal elements in the system stiffness matrix and the corresponding components of the force vector, which is easy to implement, see Equation (

23).

where

is the original diagonal elements in the stiffness matrix,

is the penalty factor, which is much larger than elements in the stiffness matrix,

is the original force vector,

is the revised force vector, and

is the predefined displacement vector. Usually,

can be set to

, where

is the largest diagonal element.

Since the indexes of the boundary nodes in the system stiffness matrix are unchanged, to enhance the efficiency of imposing boundary conditions, a preprocessing function is designed, which can determine the indexes of the positions to be modified in the stiffness matrix and force vector matrix in advance, and the indexes are stored in a specific array. When assembling the system stiffness matrix, the indexes that need to be modified can be quickly obtained, which can greatly reduce the calculation time. Thus, parallelization is not necessary when imposing boundary conditions in the SPIM simulation program.

(4) Solving the system equations. As stated in the Introduction, to enhance the calculation efficiency, the research team introduced the PARDISO solution library to solve the system equations for the face-based SPIM. The test results show that when the number of nodes is 13,710, the time to solve the system equations is only 3.077 s, which is satisfactory. Thus, OpenMP parallelization is not considered when solving the system equations. More details about solving the system equations can be seen in Reference [

13].

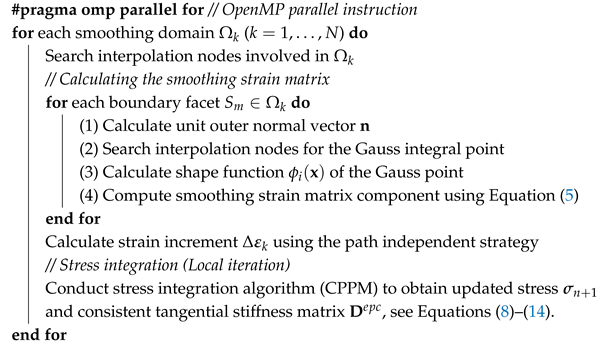

(5) Solving the strain and stress. In this part, the strain increment is first obtained by the nodal displacement increment, and then the stress field of the calculation model can be obtained using the stress integration algorithm. As introduced in

Section 3, the stress integration algorithm needs to be solved iteratively. When the iterations do not converge, the line search method and adaptive sub-step method are needed to enhance the convergence, which will occupy a lot of solving time, especially when the nonlinearity degree is high.

Similar to assembling the system stiffness matrix, solving the strain and stress is carried out based on each smoothing domain independently, without data competition and data dependence, which is suitable for parallelization. The pseudocode of solving the strain and stress using the OpenMP instruction can be seen in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Pseudocode of solving the strain and stress using the OpenMP instruction |

![Mathematics 14 00007 i002 Mathematics 14 00007 i002]() |

5. Numerical Tests

In this section, the correctness, convergence, stability, and OpenMP parallel performance of the SPIM simulation program are verified. To test the correctness, convergence, and stability, a classical simplified heterogeneous slope model is employed, and the strength reduction method is used to conduct the slope stability analysis. To test the OpenMP parallel performance, a large-scale slope model and an underground gas storage model are employed.

5.1. Correctness

This paper utilizes a classical heterogeneous slope model, and its geometry and mesh models are illustrated in

Figure 4. The mesh model is composed of 1356 nodes, 3925 tetrahedral elements, and 9153 smoothing domains. To simulate the plane strain problem, the displacement boundary conditions are set as follows: the three directions at the bottom of the model are fixed, the normal directions around the model are fixed, and the top of the model is free. Additionally, the modified Mohr–Coulomb (MC) model [

40] is employed, and the calculation parameters can be seen in

Table 1.

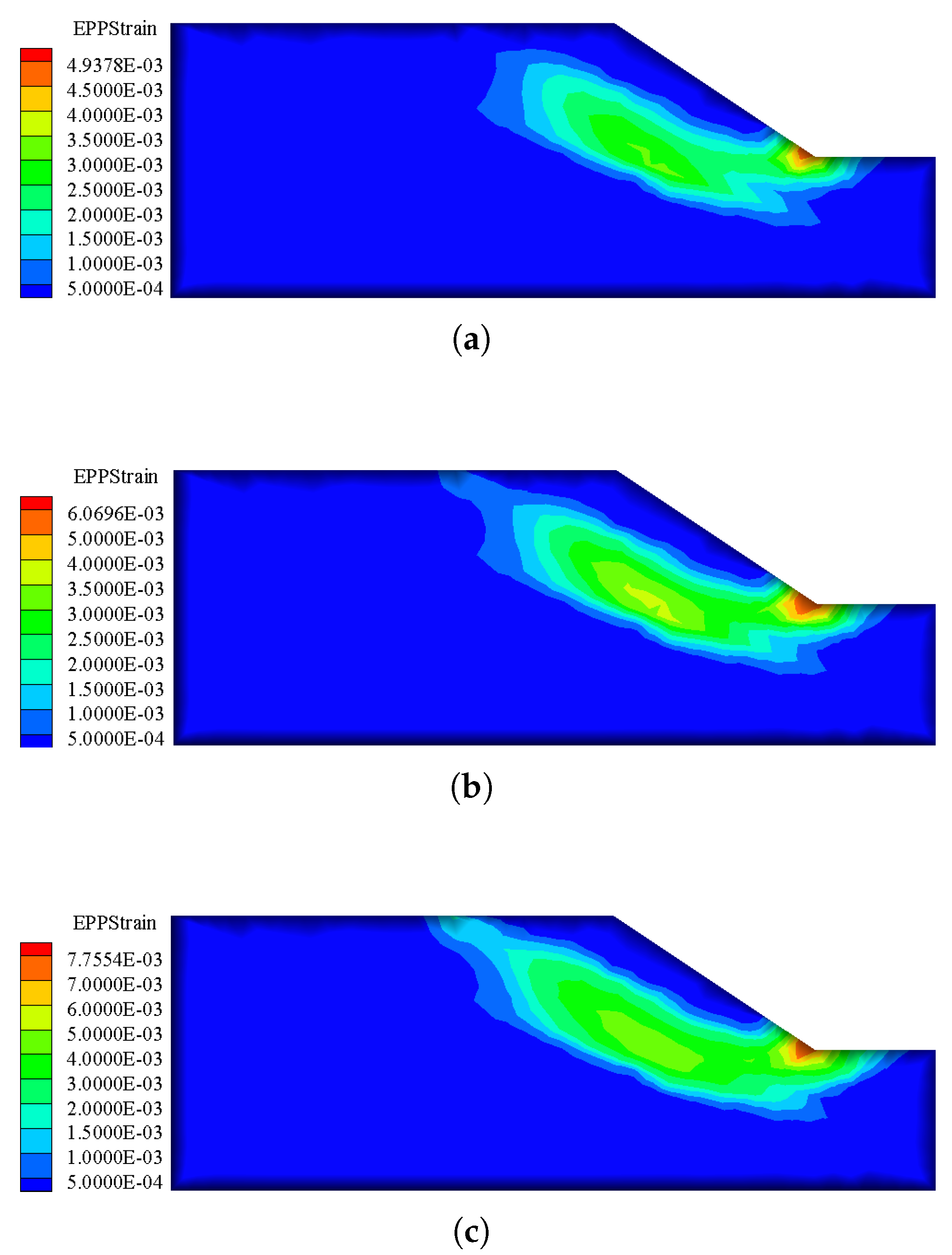

To conduct the slope stability analysis, three convergence criteria are used, including the calculation program nonconvergence (Criterion 1), displacement mutation criterion (Criterion 2), and equivalent plastic zone penetration criterion (Criterion 3). In addition, the safety factor determined by the Bishop method is 0.43, which is selected as the baseline. First, the safety factor of the simplified slope model calculated by Criterion 1 is 0.54. For Criterion 2, the Z-displacement of Point A and the X-displacement of Point B are selected as the feature points, and the displacement change curve of feature points under different reduction factors is illustrated in

Figure 5. It can be seen that when the reduction factor is 0.43, the displacement at Point A and Point B produces mutation; thus, the safety factor determined by Criterion 2 is 0.42. For Criterion 3, the counter of equivalent plastic zone under different reduction factors is illustrated in

Figure 6. When the reduction factor is 0.42, the equivalent plastic zone is not yet penetrated. When the reduction factor is 0.43, the equivalent plastic zone is penetrated. Thus, the safety factor determined by Criterion 3 is 0.42.

It can be found that the safety factor of the simplified slope model calculated by Criterion 1 is larger than that of Criterion 2 and Criterion 3. Generally, the safety factor determined by Criterion 2 and Criterion 3 is closer to the results of the limit equilibrium method than Criterion 1, which is consistent with the test results [

41]. Moreover, the safety factor determined by Criterion 2 and Criterion 3 is 0.42, which is close to the safety factor determined by the Bishop method. The numerical simulation results verify the correctness of the simulation program.

5.2. Convergence and Stability

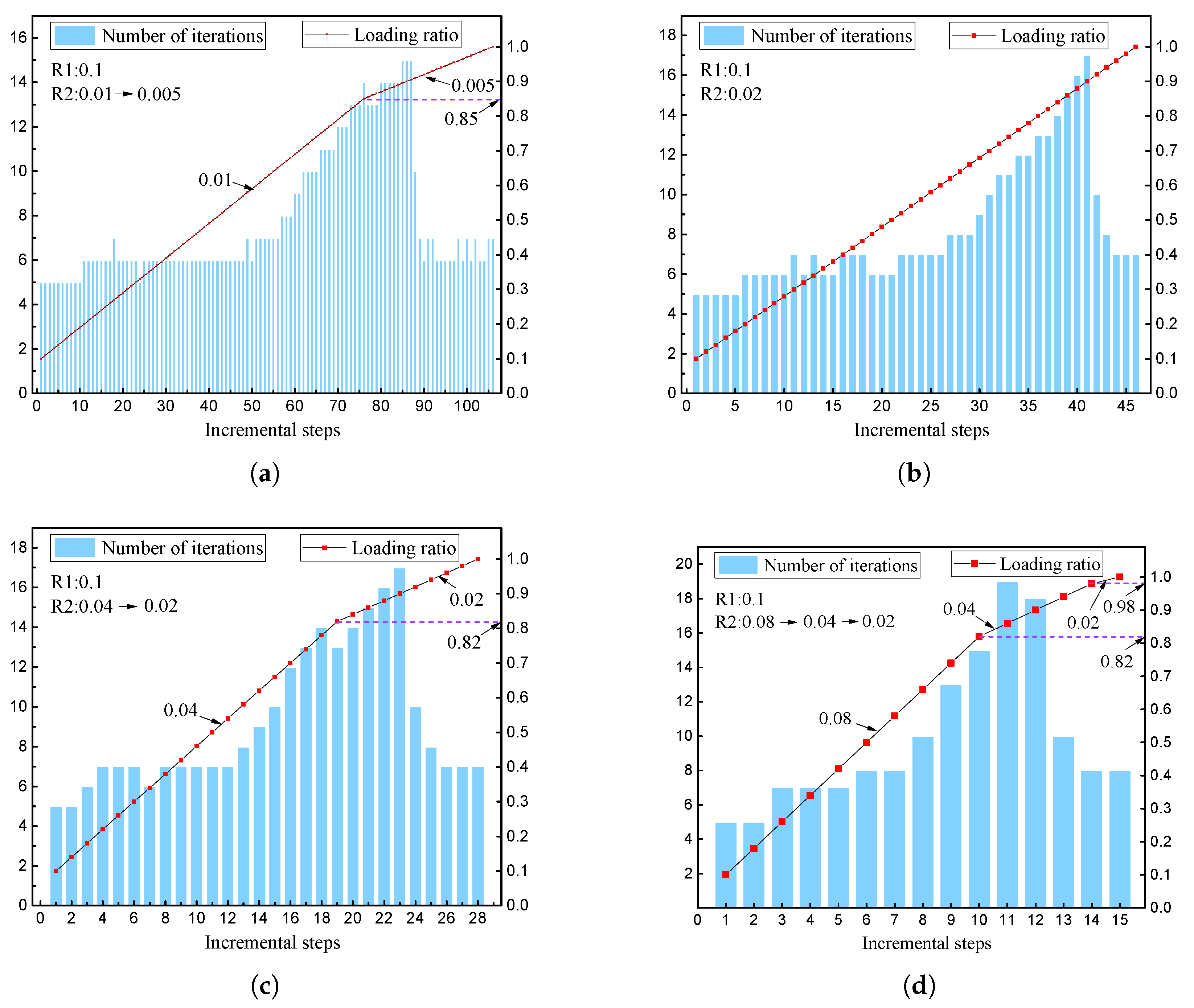

As discussed above, two effective accelerated convergence strategies are proposed to improve the convergence and stability of the simulation program. To verify this, two sets of mechanical parameters when the reduction factors are 0.42 and 0.54 are selected, which correspond to different nonlinearity degrees, and the latter one is higher. Moreover, the incremental step size R2 is set to 0.04, 0.08, 0.1, and 0.2 when the reduction factor is 0.42, while the R2 is set to 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, and 0.08 when the reduction factor is 0.54.

When the reduction factor is 0.42, the initial step size R1 is 0.2, and the incremental step size R2 is unchanged for all cases. Moreover, the average number of iterations is 6.67, 7.09, 7.22, and 8.20 for each case, and the maximum number of iterations is 10; see

Figure 7. When the reduction factor is 0.54, the initial step size R1 is 0.1, and the incremental step size R2 is not always unchanged for all cases. For example, when the R2 is 0.01, 0.04, and 0.08, the analysis program cannot converge unless the R2 is lessened. Moreover, the average number of iterations is 7.81, 8.19, 9.21, and 9.86 for each case, and the maximum number of iterations is 19; see

Figure 8. Thus, the analysis program maintains good convergence and stability. In addition, when the reduction factor is 0.42, the changes in the absolute value of the maximum unbalanced force (MaxUF) and the maximum displacement increment (MaxDU) within the last increment step are listed in

Table 2. From

Table 2, it can be found that the rate of convergence is quadratic even for large load increments.

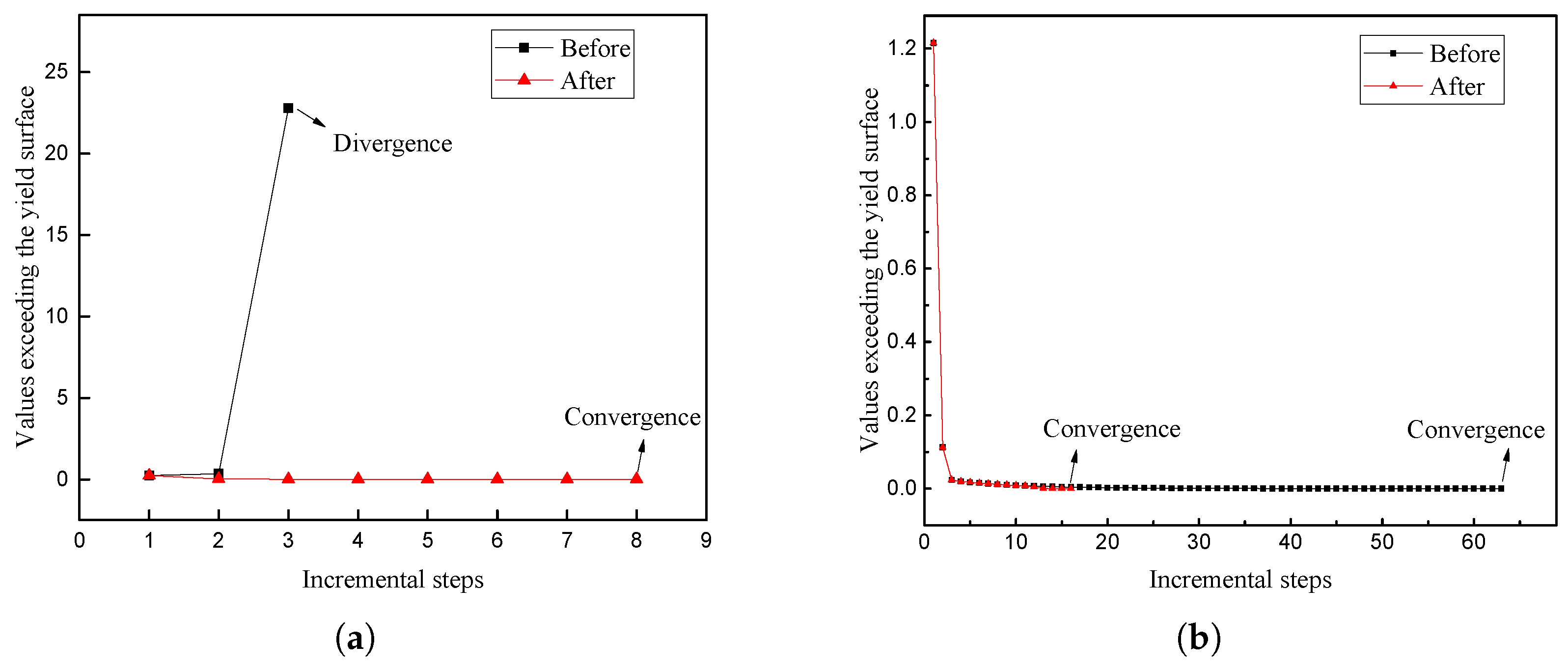

In this paper, the line search method is used to improve the convergence of the local iteration. To verify this, the mechanical parameters are selected when the reduction factor is 0.54 and the R2 is set to 0.08. First, two integration points are selected, and the convergence of the local iteration is tested. When the local iteration does not converge, the line search method is used to reduce the step size, and the local iteration can achieve convergence. When the local iteration can converge but the number of iterations is large, the line search method is used to enlarge the step size, and the convergence is better; see

Figure 9.

5.3. OpenMP Parallel Performance

As discussed above in

Section 4, the OpenMP feasibility analysis of the SPIM simulation program is conducted, and two modules of assembling the stiffness matrix and solving the stress and strain are parallelized. To verify the performance of the OpenMP parallel program, two large-scale models are employed, including a real slope model and a simplified underground gas storage model. In this paper, the CPU of the computing platform is Intel Core i5-13500HX, and the number of cores is 20.

5.3.1. Real Slope Model

Case 1 is a heterogeneous slope model, which is composed of 11,292 nodes, 52,600 tetrahedral elements, and 110,066 smoothing domains, and its geometry and mesh model can be seen in

Figure 10. The lithology of the slope is gneiss with different degrees of weathering, and its calculation parameters are shown in

Table 3.

For Case 1, the safety factor of the real slope model calculated by Criterion 1 is 1.30. To better test the OpenMP parallel performance, this paper designs the following test schemes. (1) The reduction factor of the slope is set to 1.00 and 1.30, which represent different mechanical parameters and different nonlinearity degrees, respectively. The larger the reduction factor, the higher the nonlinearity degree and the longer the solving time. (2) For each set of mechanical parameters, the incremental step size R2 is set to 0.01, 0.02, and 0.04. Moreover, the smaller the R2, the longer the solving time.

Table 4 is the solving time and speedup ratio of different test schemes. The test results indicate the following: (1) when the reduction factor is 1.00, with the increase in the R2, the speedup ratio is 7.70, 7.14, and 6.04, which decreases gradually; (2) when the reduction factor is 1.30, with the increase in the R2, the speedup ratio is 8.08, 7.78, and 6.46, which decreases gradually; (3) when the reduction factor is 1.00 and 1.30, the average speedup ratios are 6.96 and 7.44, respectively; (4) when the R2 is the same, the larger the reduction factor, the larger the speedup ratio. The above results show that the OpenMP parallel method can effectively enhance the computational efficiency of the simulation program and achieve a speedup ratio of 8.08 at most. Moreover, as the amount of calculation and the nonlinearity degree increases, the speedup ratio shows an increasing trend.

To further verify, this paper compares the solving time of the last 10 loading steps, before and after the parallelization.

Figure 11 provides the test results when the reduction factor is 1.00. When R2 is 0.01, the minimum speedup ratio is 8.67, the maximum value is 14.50, and the average value is 11.89. When R2 is 0.02, the minimum speedup ratio is 11.00, the maximum value is 13.00, and the average value is 12.36. When R2 is 0.04, the minimum speedup ratio is 10.67, the maximum value is 14.00, and the average value is 12.55.

Figure 12 provides the test results when the reduction factor is 1.30. When R2 is 0.01, the minimum speedup ratio is 8.25, the maximum value is 13.00, and the average value is 10.39. When R2 is 0.02, the minimum speedup ratio is 11.00, the maximum value is 13.50, and the average value is 11.60. When R2 is 0.04, the minimum speedup ratio is 10.67, the maximum value is 11.33, and the average value is 11.00. The test results show that the acceleration effect of the OpenMP parallelization is more prominent for each loading step and achieves a speedup ratio of 14.50 at most.

5.3.2. Simplified Underground Gas Storage Model

Case 2 is a simplified underground gas storage model, and its geometry and mesh model can be seen in

Figure 13. The lithology of the underground gas storage model from top to bottom is mudstone, salt rock, and mudstone, and its calculation parameters are shown in

Table 5. To further verify, this paper designs the following test schemes: (1) the width of the calculation model is set to 40 m, 80 m, and 120 m (Model 1∼Model 3); (2) for each calculation model, the R2 is set to 0.01, 0.02, and 0.04. The mesh size of the three models is set to be the same, and the details of these calculation models are shown in

Table 6.

Table 7 is the solving time and speedup ratio of different test schemes. The test results indicate the following: (1) for Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, the average speedup ratio under different R2 is 7.41, 7.53, 7.78; (2) for Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3, with the increase in the R2, the speedup ratio decreases gradually; (3) when the R2 is the same, as the amount of calculation increases, the speedup ratio shows an increasing trend. The above results show that the OpenMP parallel method can effectively enhance the computational efficiency of the simulation program and achieve a speedup ratio of 7.78 at most.

To further verify, this paper compares the solving time of the last 10 loading steps before and after the parallelization when R2 is 0.01; see

Figure 14. For Model 1, the minimum speedup ratio is 8.00, the maximum value is 11.00, and the average value is 9.05. For Model 2, the minimum speedup ratio is 8.50, the maximum value is 11.33, and the average value is 9.88. For Model 3, the minimum speedup ratio is 8.56, the maximum value is 12.57, and the average value is 9.73. The test results show that the acceleration effect of the OpenMP parallelization is more prominent for each loading step and achieves a speedup ratio of 12.57 at most.

6. Discussion and Future Work

To improve the performance of the SPIM simulation program, this paper adopts the line search method and the adaptive sub-step method to improve the convergence and stability. Moreover, the OpenMP parallelization design is carried out for the SPIM simulation program. The test results show that the program has an asymptotic quadratic convergence and satisfactory stability. In addition, the speedup ratio of the OpenMP parallel program reached up to 14.50 when using a computing platform with 20 CPU cores.

However, the calculation efficiency of the SPIM simulation program still needs to be improved. From

Section 4, it can be known that two modules of assembling the stiffness matrix and solving the stress and strain have been parallelized. Due to the data competition in assembling the stiffness matrix, this paper adopts the sleep-waiting lock operation, which can ensure that at most only one thread can pass through the data competition region at any time and can avoid data competition. However, the sleep-waiting lock operation will cause a waste of computing resources. To avoid this situation, researchers usually use multi-color dyeing algorithms to partition the background mesh, and the associated mesh can be manipulated by different threads [

42,

43]. However, since the internal smoothing domain of the face-based SPIM is constructed using adjacent mesh elements, and the nodes associated with the smoothing domain may be involved in multiple mesh elements, in FEM, the nodes required for Gaussian point interpolation are limited to the element vertices where the Gaussian points are located. In SPIM, the interpolation nodes will cross the background element, which increases the complexity of the dyeing process. Thus, designing an applicable multi-color dyeing algorithm for the face-based SPIM is necessary.

Another method is to parallelize the SPIM simulation program using the GPU. At present, to achieve high-performance computing, GPU parallel design has been successfully applied to geotechnical problems. For example, Chen accelerated the SPH particle flow simulation program using the GPU, and the calculation efficiency was achieved at 160 times that of a single CPU [

44]. Dong proposed a GPU-based MPM parallelization method; when simulating the interaction between the structural unit and soil, the maximum single-precision speedup ratio of the GPU reached 30, and the double-precision speedup ratio was 20 [

45]. Moreover, there are many studies on GPU parallel implementation of the FEM [

26,

27,

28,

29,

46]. At present, the research on GPU parallelization for SPIM has not been seen yet, which is a direction worthy of study.

7. Conclusions

To improve the performance of the SPIM simulation program, the line search algorithm, the adaptive sub-step method, and the OpenMP parallel method are adopted to enhance the convergence, stability, and computational efficiency. To verify, three different cases are adopted for testing in this paper. The results are as follows: (1) The test results of the slope stability analysis show that the safety factor calculated by the SPIM program is 0.42, which is close to the safety factor of 0.43 calculated by the Bishop method, indicating the correctness of the program. (2) The SPIM program can effectively solve the problems of non-convergence or slow convergence during the local iteration process. For the global iteration, the simulation program can achieve an asymptotic quadratic convergence and satisfactory stability, even in a critical state. (3) The test results of two large-scale models show that the SPIM program can achieve a speedup ratio of 6 to 8 on a computing platform with 20 CPU cores, and the maximum speedup ratio for a single load step can reach 14.50.

However, the calculation efficiency of the SPIM program still needs to be improved. For example, a multi-color dyeing algorithm suitable for face-based SPIM should be established to avoid the data competition problem encountered in assembling the stiffness matrix. Moreover, the GPU parallelization analysis and design for the SPIM program require further research.