An Age-Structured Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate

Abstract

1. Introduction

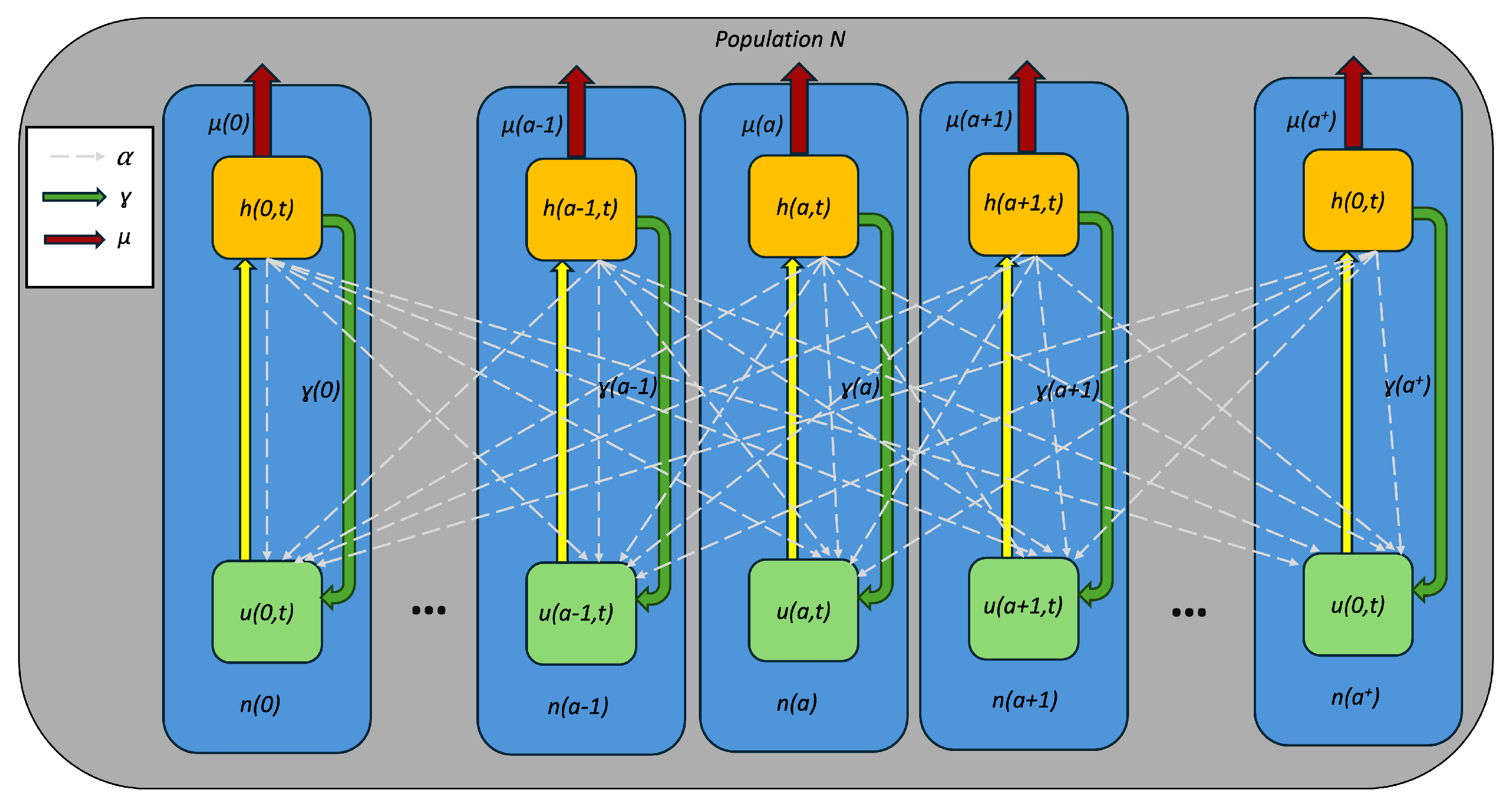

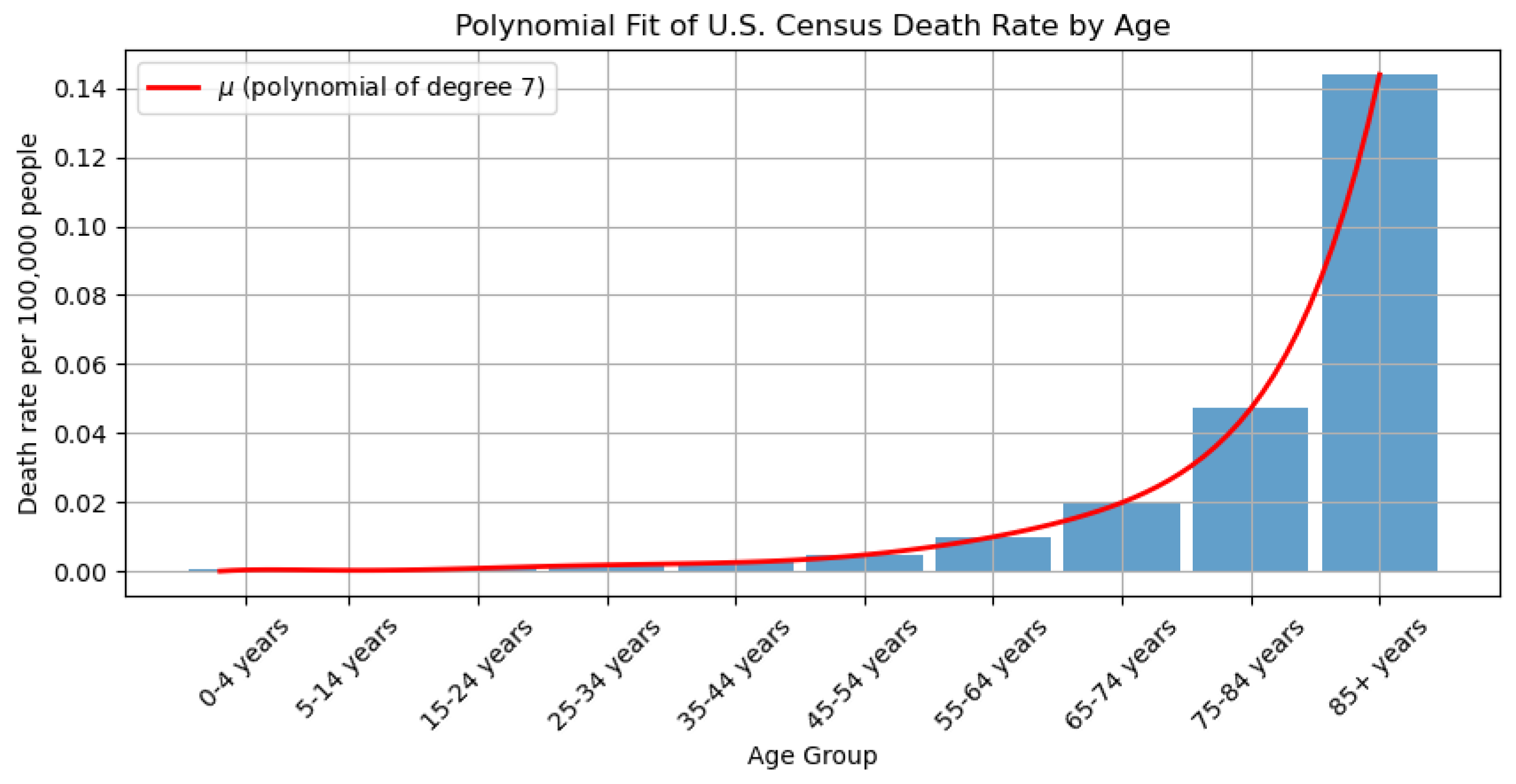

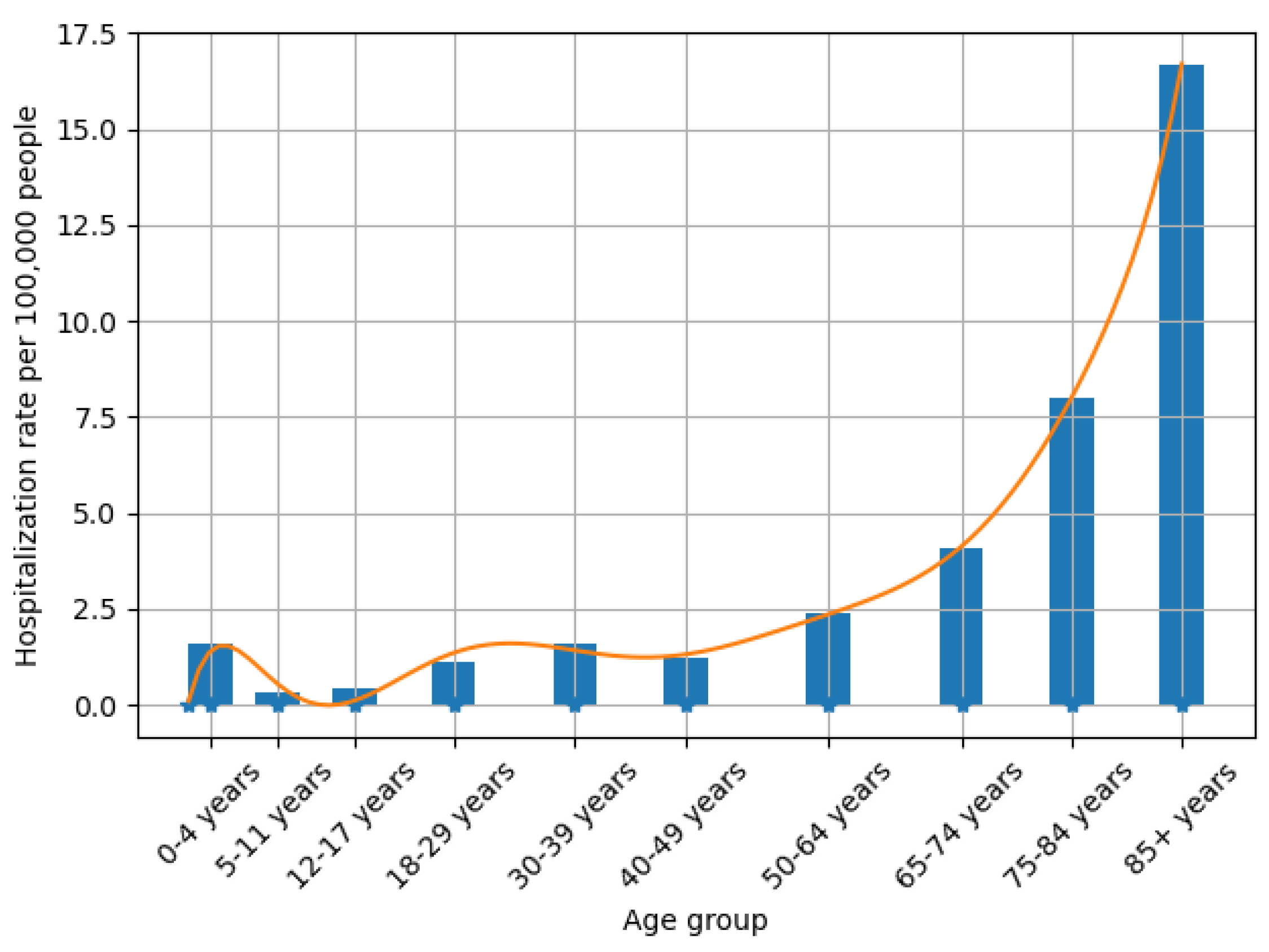

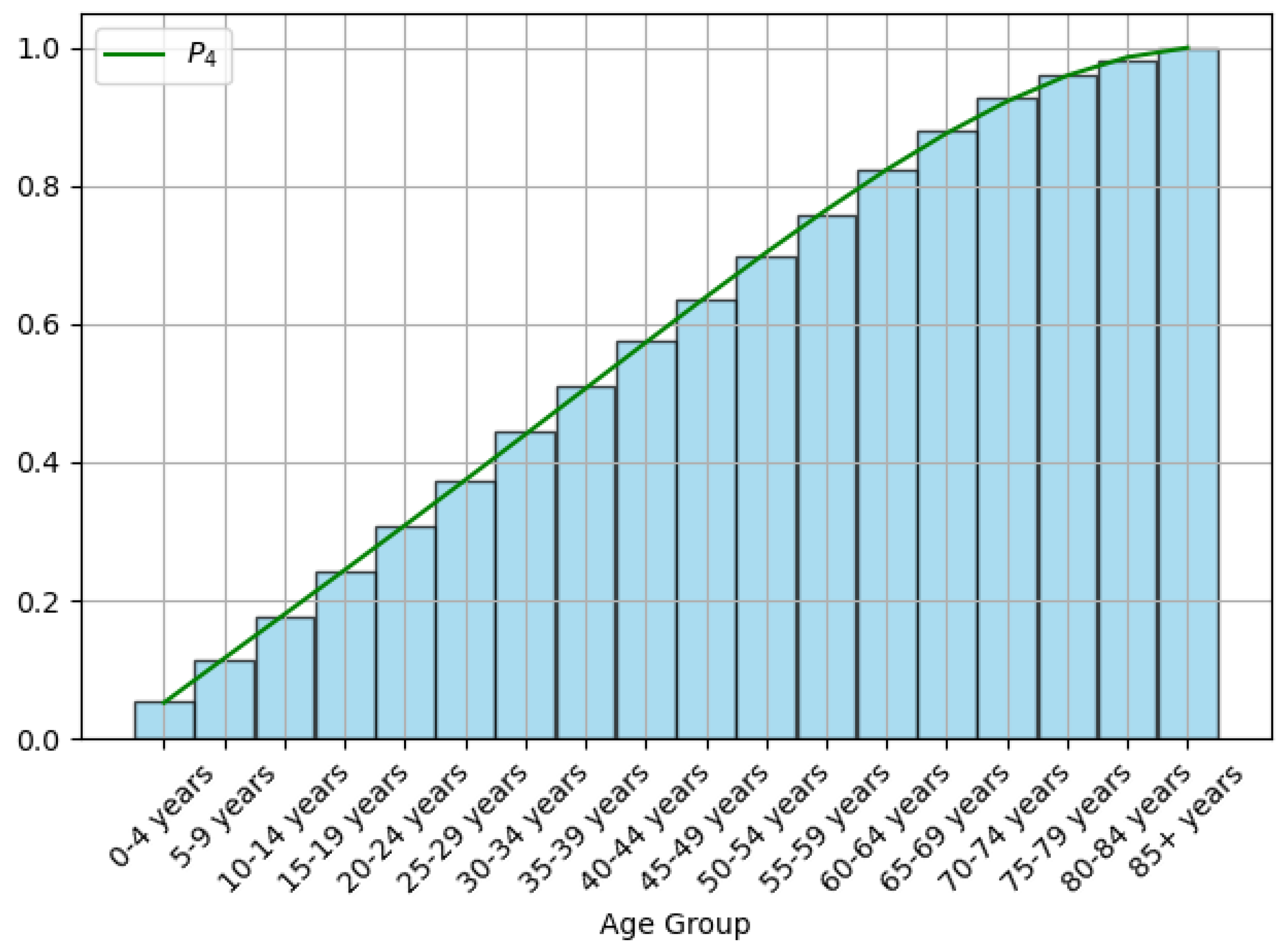

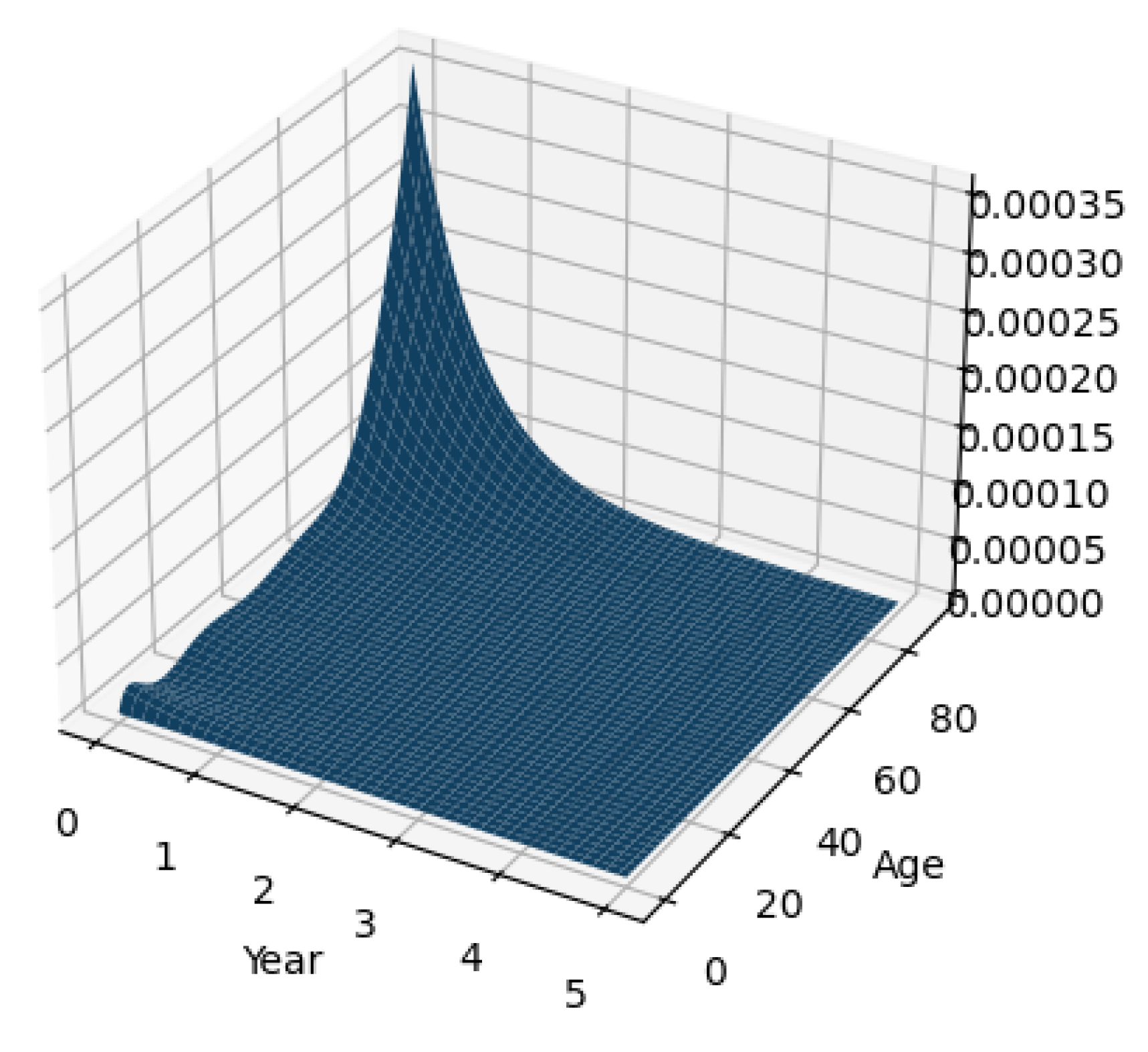

2. Age-Structured PDE Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate

- (A1)

- with , ;

- (A2)

- with , ;

- (A3)

- with , ; and

- (A4)

- with , .

- (i)

- A is the infinitesimal generator of a -semigroup ;

- (ii)

- F is Lipschitz continuous in X; and

- (iii)

- the abstract equation a unique classic solution on a maximal interval , which satisfieswhere either or .

3. PINN Model Development and Simulation

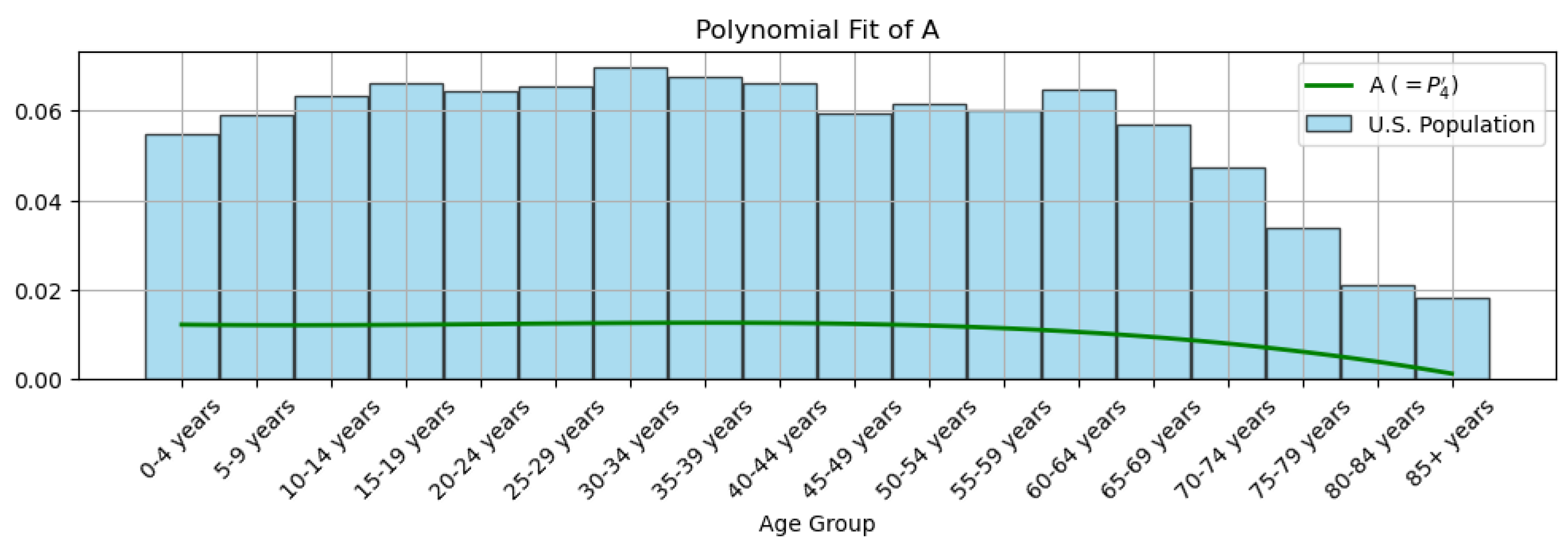

3.1. Data Processing

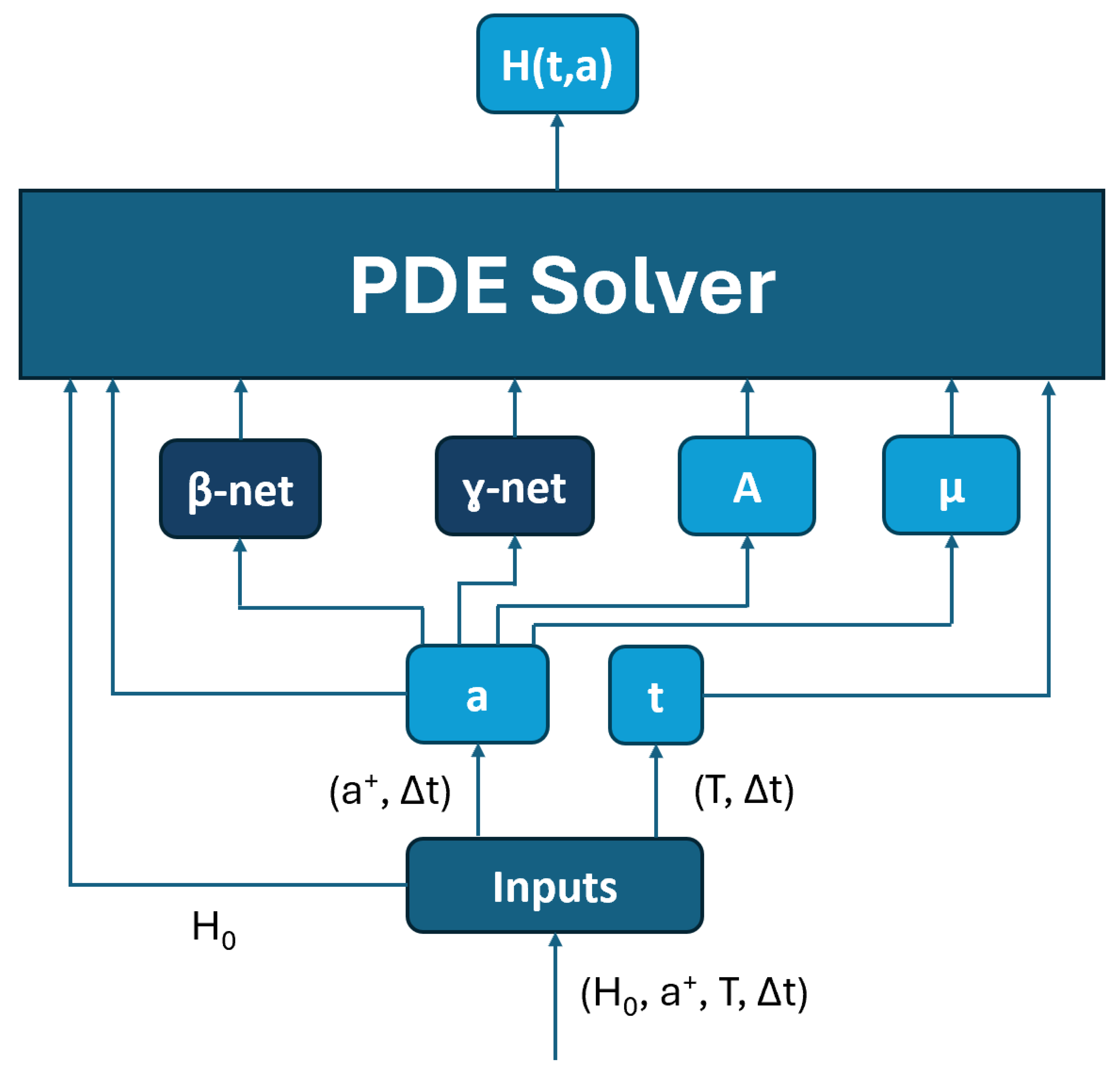

3.2. PINN Model Architecture

- The t block generates a discrete time interval needed for other blocks based on the step size to discretize the time interval .

- The a block discretizes the age interval as a discrete interval needed for other blocks based on .

- The A block and block calculate the needed values , , and for , respectively.

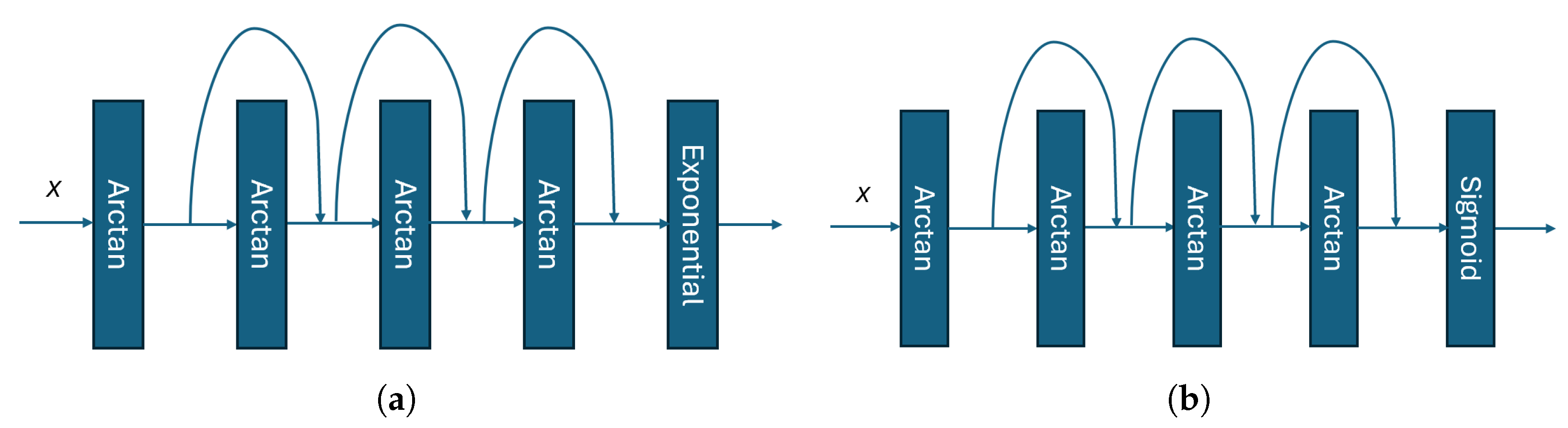

- The -net and -net approximate and , respectively. Both the -net and -net utilize the residual network architecture, as illustrated in Figure 8.

3.3. Forward Propagation Process

| Algorithm 1 Forward propagation |

|

3.4. Training Process

- (1)

- (2)

- The optimization problem during the training process is solved using the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm [26] instead of traditional gradient-based ML training algorithms, as calculating gradients would be highly memory-intensive. The PSO algorithm enables us to train the model on a MacBook Pro laptop with 16 GB of memory.

- (3)

- The PDE-Solver block can be implemented using alternative algorithms to enhance computational efficiency, including traditional numerical schemes or modern ML-based approaches. When ML-based methods are employed for solving PDEs, an additional physics-informed term must be incorporated into the loss function defined by (12) to compensate for the inherent opacity of NNs. In contrast, such a term is unnecessary for classical numerical solvers, as their error behavior is governed by the underlying numerical scheme.

- (4)

- The sub-NNs, β-net and γ-net, can be implemented using other NN architectures instead of those shown in Figure 8, and can be trained using different algorithms given sufficient computational resources.

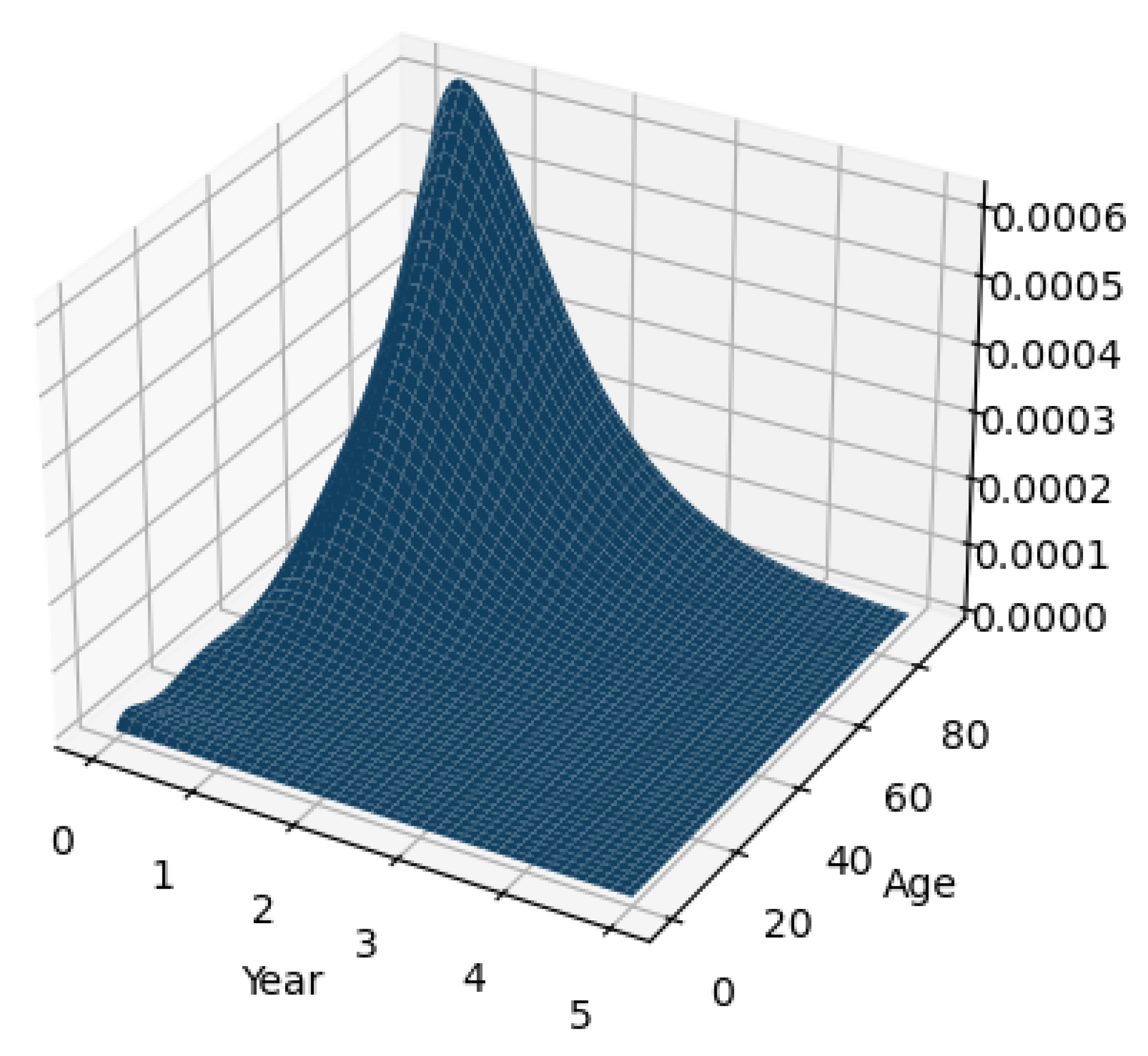

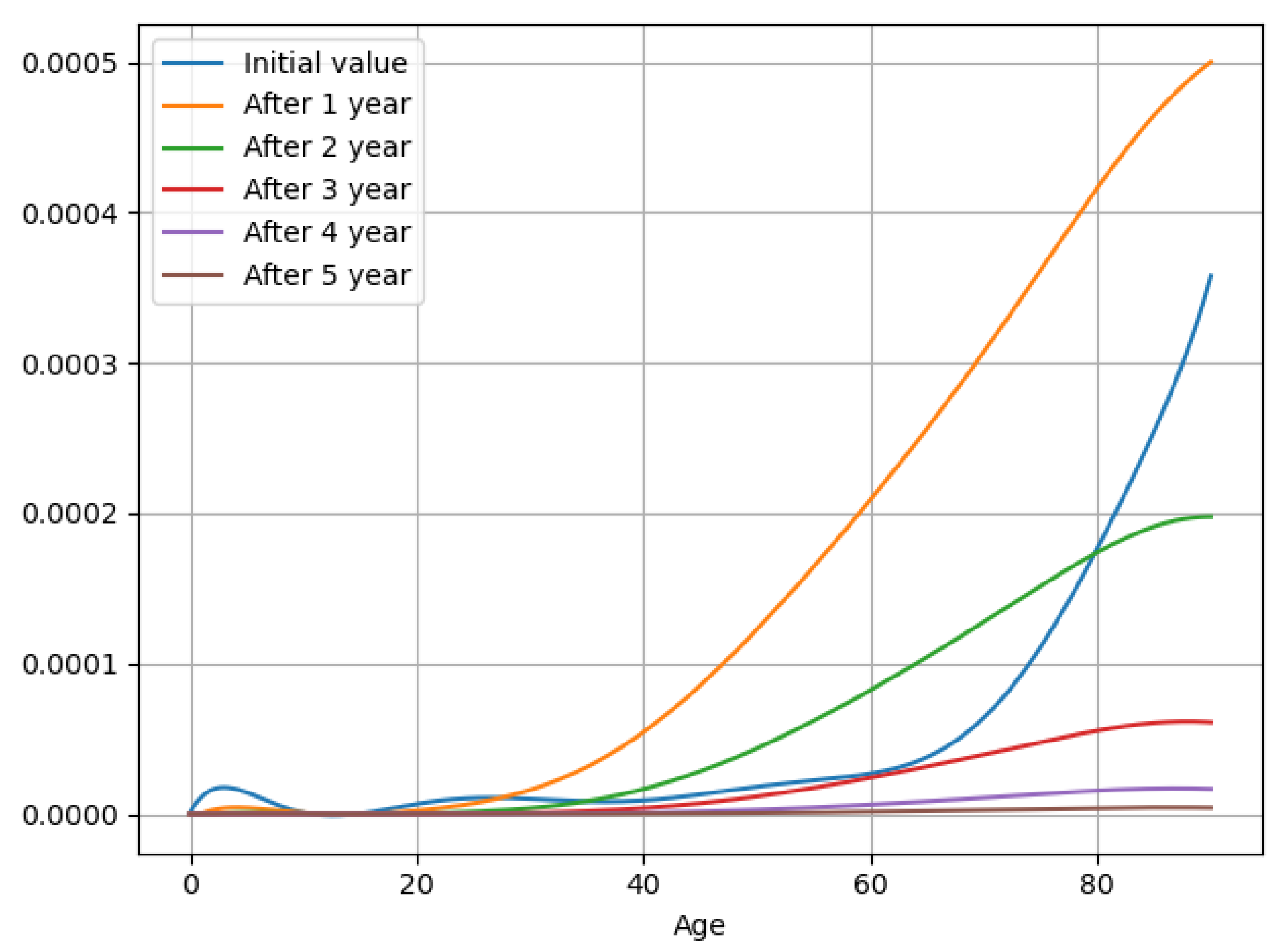

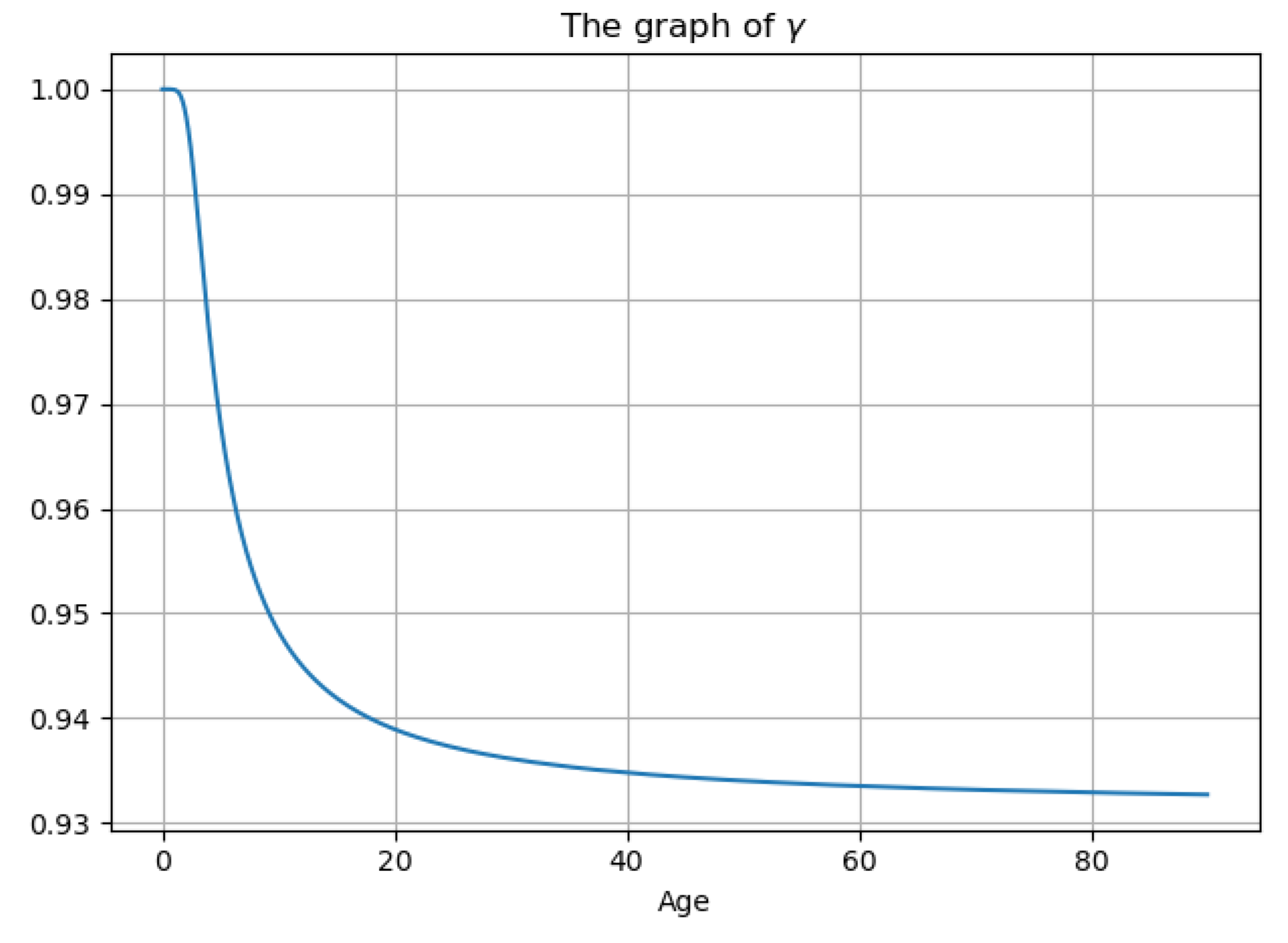

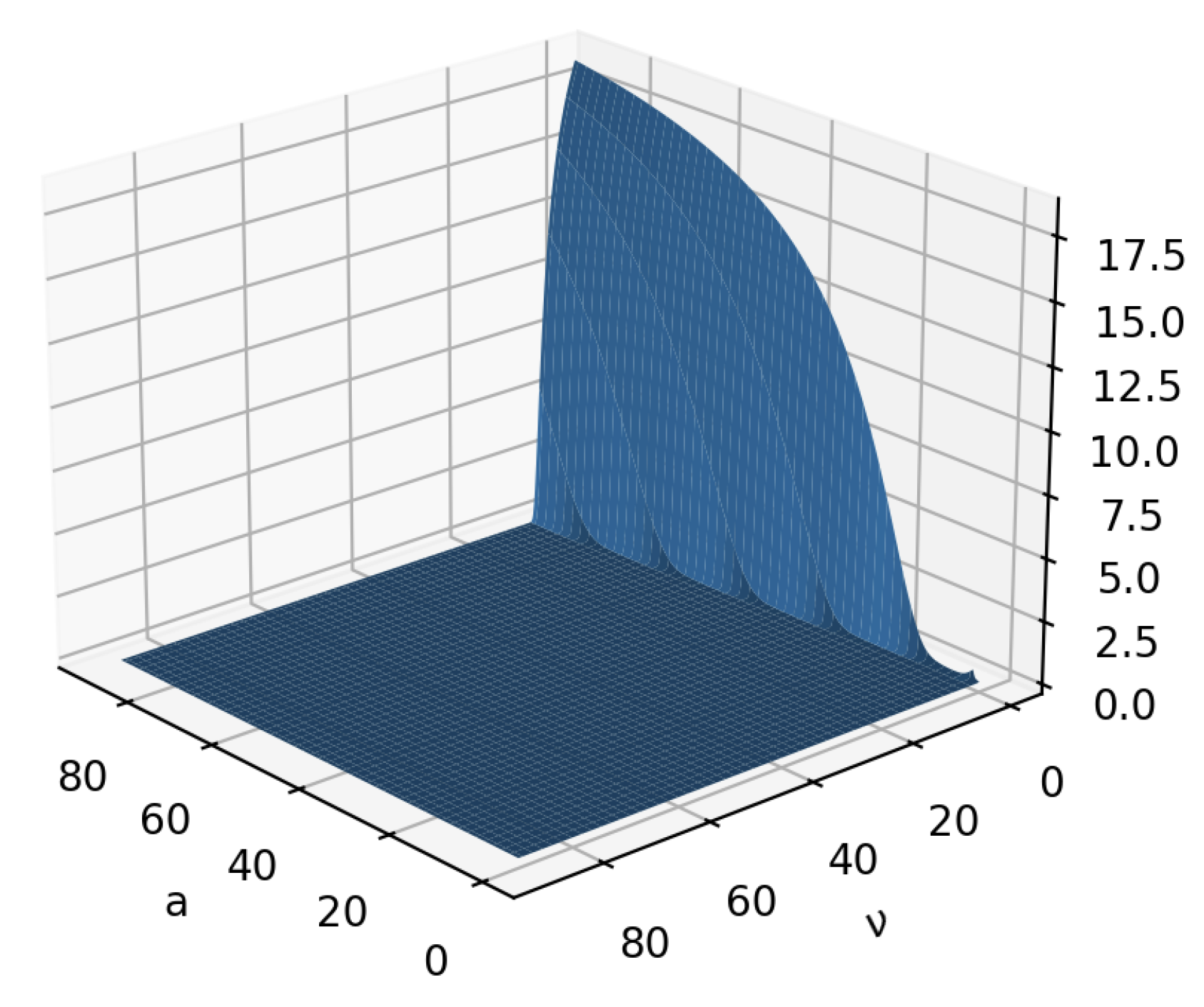

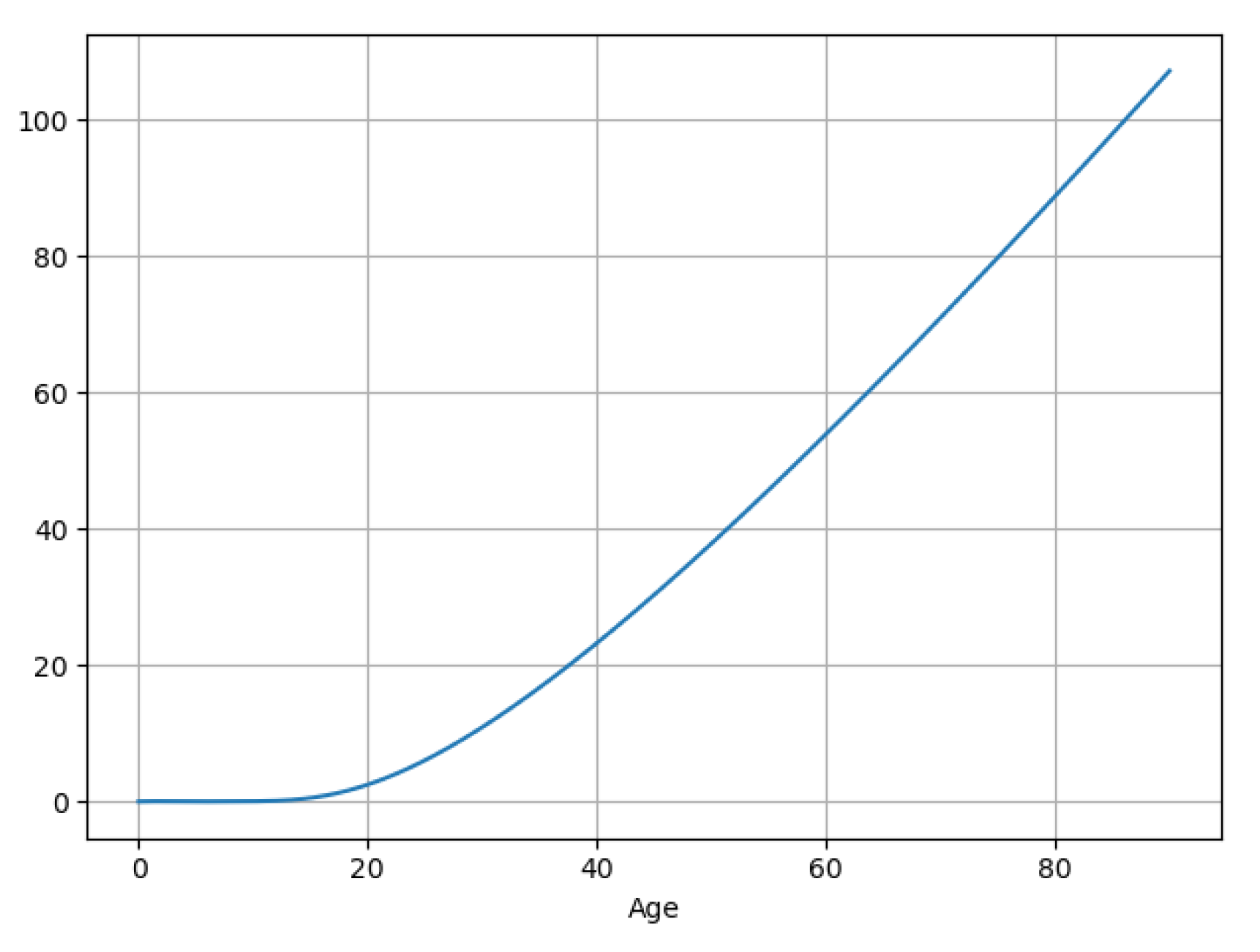

3.5. Experiment Results

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naseer, S.; Khalid, S.; Parveen, S.; Abbass, K.; Song, H.; Achim, M.V. COVID-19 outbreak: Impact on global economy. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1009393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- National Flu and COVID-19 Surveillance Reports. UK Health Security Agency. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-flu-and-covid-19-surveillance-reports-2024-to-2025-season (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Surveillance and Updates on COVID-19. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/situation-updates (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Abernethy, G.M.; Glass, D.H. Optimal COVID-19 lockdown strategies in an age-structured SEIR model of Northern Ireland. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20210896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambalarajan, V.; Mallela, A.R.; Sivakumar, V.; Dhandapani, P.B.; Leiva, V.; Martin-Barreiro, C.; Castro, C. A six-compartment model for COVID-19 with transmission dynamics and public health strategies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, F. Mathematical epidemiology: Past, present, and future. Infect. Dis. Model. 2017, 2, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Shi, J.; Shuai, Z.; Wu, Y. Evolution of Dispersal in Advective Patchy Environments. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 33, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACiupeanu; Varughese, M.; Roda, W.C.; Han, D.; Cheng, Q.; Li, M.Y. Mathematical modeling of the dynamics of COVID-19 variants of concern: Asymptotic and finite-time perspectives. Infect. Dis. Model. 2022, 7, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Yuan, X. A hybrid Lagrangian–Eulerian model for vector-borne diseases. J. Math. Biol. 2024, 89, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyaniwura, S.A.; Falcão, R.C.; Ringa, N.; Adu, P.A.; Spencer, M.; Taylor, M.; Colijn, C.; Coombs, D.; Janjua, N.Z.; Irvine, M.A.; et al. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 in British Columbia: An age-structured model with time-dependent contact rates. Epidemics 2022, 39, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiseleva, O.; Yakovlev, S.; Chumachenko, D.; Kuzenkov, O. Exploring Bifurcation in the Compartmental Mathematical Model of COVID-19 Transmission. Computation 2024, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Li, C.; Warner, J. Structured mathematical models to investigate the interactions between Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites and host immune response. Math. Biosci. 2019, 310, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndaïrou, F.; Area, I.; Nieto, J.J.; Torres, D.F.M. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 135, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, G.; Zhao, X.E. An Epidemic Model with Infection Age and Vaccination Age Structure. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, N.; Xu, H.; Morani, A.H.; Shokri, A.; Mukalazi, H. Exploring local and global stability of COVID-19 through numerical schemes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Tang, S. Stability analysis of the COVID-19 model with age structure under media effect. Comp. Appl. Math. 2023, 42, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Chief Declares End to COVID-19 as a Global Health Emergency. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136367 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Cuomo, S.; Cola, V.S.D.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific Machine Learning Through Physics–Informed Neural Networks: Where we are and What’s Next. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ying, C.; Feng, Y.; Su, H.; Zhu, J. Physics-Informed Machine Learning: A Survey on Problems, Methods and Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.08064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Shi, R.Z.; Wang, M. A physics-informed neural network model for social media user growth. Appl. Comput. Intell. 2024, 4, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabczyk, J. Mathematical Control Theory: An Introduction; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- The U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S0101?q=us%20age%20distribution (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kochanek, K.D.; Murphy, S.L.; Xu, J.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2022. NCHS Data Brief No. 492. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db492.htm (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kincaid, D.; Cheney, W. Numerical Analysis: Mathematics of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ji, G. A Comprehensive Survey on Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm and Its Applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 931256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notations | Meaning |

|---|---|

| N | Total population (constant) |

| Cohort of hospitalized patients of ages in the interval at time t due to COVID-19 | |

| Cohort of other individuals of ages in the interval at time t | |

| Hospitalization rate of age a at time t due to COVID-19 | |

| Density function of the age distribution of N | |

| Per capita census death rate of age a of N | |

| Entering coefficient of hospitalized patients of age a due to COVID-19 | |

| Kernel to represent the impact to the patient cohort of age a from patient cohorts of age | |

| Removal coefficient of hospitalized patients of age a due to COVID-19 |

| Swarm Size | 20 | Dimension of the Search Space | 97 |

| Maximum Number of Iterations | 50 | Search Space Bounds | |

| Cognitive Coefficient | 2 | Social Coefficient | 1 |

| Inertia Weight | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kong, L.; Shi, R.Z.; Wang, M. An Age-Structured Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate. Mathematics 2026, 14, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010058

Kong L, Shi RZ, Wang M. An Age-Structured Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Lingju, Ryan Z. Shi, and Min Wang. 2026. "An Age-Structured Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010058

APA StyleKong, L., Shi, R. Z., & Wang, M. (2026). An Age-Structured Model for COVID-19 Hospitalization Rate. Mathematics, 14(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010058