Efficient Multiple Path Coverage in Mutation Testing with Fuzzy Clustering-Integrated MF_CNNpro_PSO

Abstract

1. Introduction

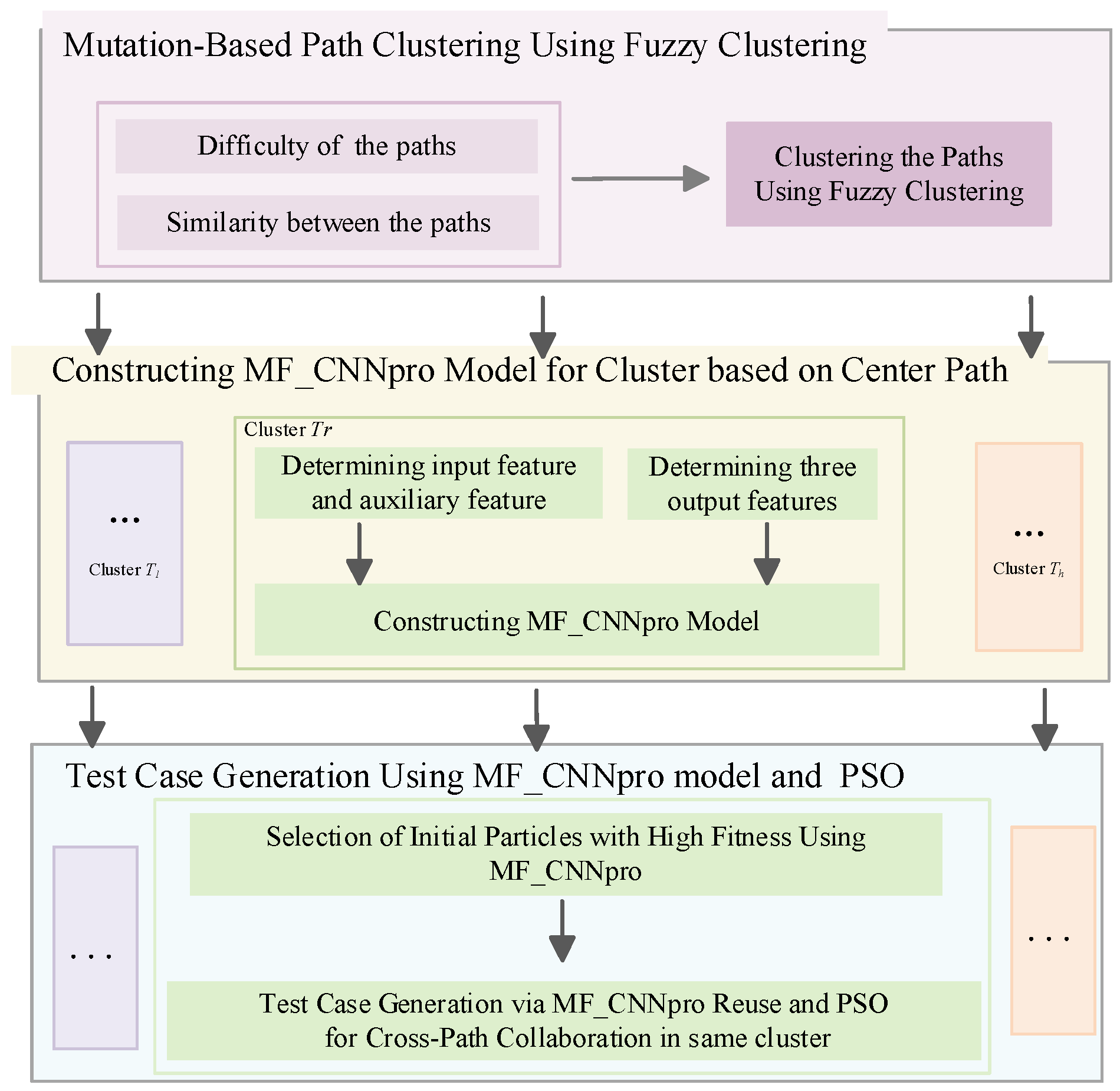

- Fuzzy Clustering for Path Grouping: This method groups mutation-based paths into the same cluster based on their similarity while allowing a single path to belong to multiple clusters. The fuzzy clustering approach more accurately reflects the real-world relationships between paths, where the boundaries of path similarity are often ambiguous and categories may overlap.

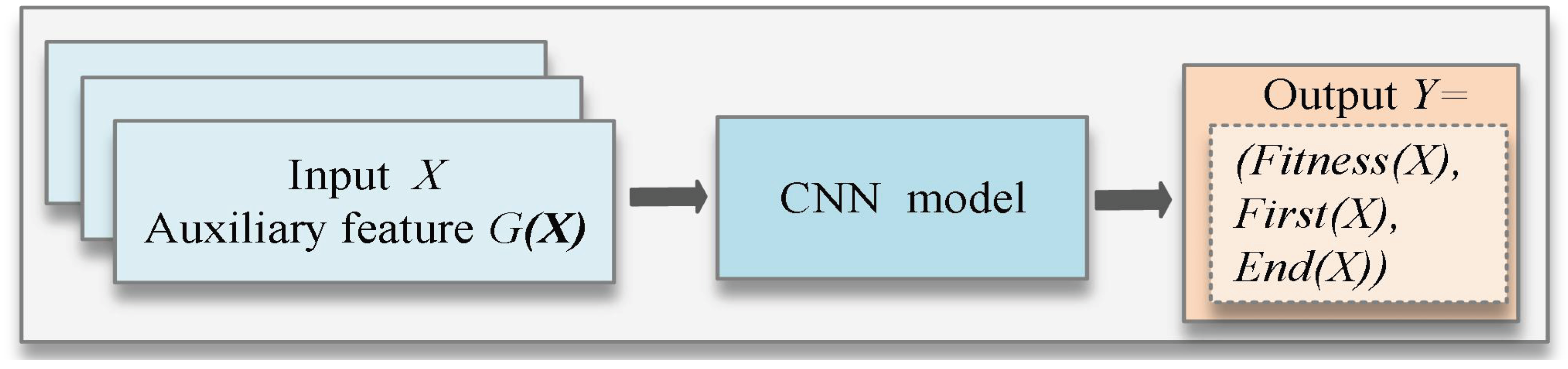

- Enhanced MF_CNNpro Model Construction with Multi-Feature Integration for Improved Prediction Accuracy: A MF_CNNpro model is constructed for each cluster, rather than for each path within the cluster, significantly reducing the cost of constructing and training surrogate models. In the model, the input features are the program’s inputs, while the traversal path serves as an auxiliary feature, enriching the model with additional diversity information. The output consists of three features. In addition to fitness as a feature (as in traditional models), two extra features are introduced, highlighting the differences between other paths and the center path. This design enables the model to generate differentiated predictions even when different paths share the same fitness value, addressing the “single-value confusion” problem common in traditional models. As a result, the model enhances both the discriminability and practical value of the prediction results.

- Efficient Test Case Generation via MF_CNNpro Reuse and PSO for Cross-Path Collaboration: A single MF_CNNpro model for each cluster can estimate high-fitness particles for multiple paths as initial particles in the particle swarm. The “one-time modeling, multiple reuse” mechanism significantly improves the model’s efficiency. If a generated particle fails to provide optimization value for a current target path, it can be evaluated to determine whether it is useful for other paths within the cluster. This strategy reduces the number of redundant predictions. By efficiently reusing the MF_CNNpro model and facilitating cross-path collaboration during the particle swarm iteration, this approach ensures prediction accuracy while significantly improving the efficiency of test case generation. Additionally, improved PSO utilizes a hypercube to define the search space and guides the particle search by handling boundary values, thereby preventing particles from getting trapped in local optima.

2. Background

2.1. Mutation-Based Path

2.2. Test Data Generation Using Evolutionary Algorithms

2.3. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

3. The Proposed Method

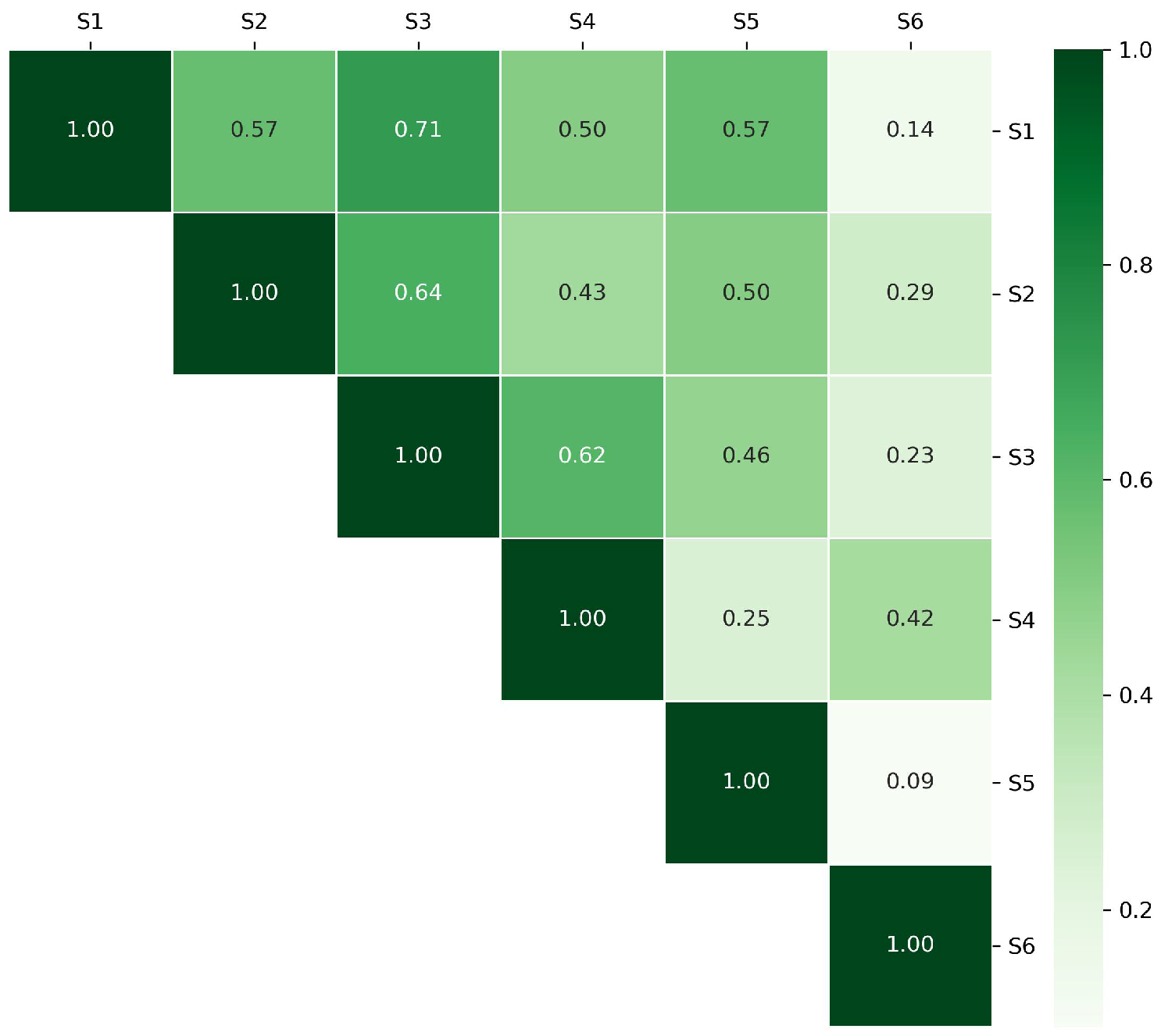

3.1. Mutation-Based Path Clustering Using Fuzzy Clustering

- The number of mutant branches included in the path.

- The number of operators and operands involved in the path.

- The density of operators within the path, where the presence of multiple operators in the same expression increases complexity.

- The number of special operators, such as ternary operators, lambda functions, and regular expression metacharacters, which increase the complexity of the path.

- Short paths with weak overlaps across multiple long paths (e.g., a short path covering 30% of two distinct long paths) exhibit low similarity to both long paths. This prevents them from being ambiguously assigned to multiple clusters.

- Long paths with low branch overlap (e.g., 20% shared branches) are distinctly separated into different clusters, avoiding blurry cluster boundaries. As a result, clusters become purer, with defined path characteristics and significantly reduced overlap.

- Paths grouped based on the max-based similarity metric share a high proportion of mutation branches relative to the longer path, ensuring that their fault detection characteristics (e.g., critical branch coverage, branch dependency relationships) are highly consistent.

- Shared models trained on homogeneous clusters are more likely to generalize effectively to unseen paths within the same cluster, thus avoiding overfitting to heterogeneous paths. This reduces the “prediction bias-induced ambiguous membership” and indirectly mitigates the negative effects of clustering overlap.

- Separation: Paths in different clusters exhibit distinct coverage patterns, preventing redundant model training. For instance, there is no need to train separate models for clusters that exhibit significant overlap.

- Completeness: All paths with similar coverage patterns, regardless of their length, are grouped into the same cluster. For example, a short path covering 80% of a long path’s branches will be clustered with the long path, ensuring that critical coverage patterns are captured without introducing overlap due to weak correlations.

| Algorithm 1 Fuzzy Clustering of Paths |

| Input: (Ordered path set); (Similarity matrix of paths); U (Threshold value); Output: (Cluster set)

|

3.2. Constructing MF_CNNpro Model for Cluster Based on the Center Path

| Algorithm 2 Establish and train MF_CNNpro Model |

| Input: Sample data ; cluster center path ; training/test set partition ratio Output: Trained MF_CNNpro model; model performance evaluation results on the test set

|

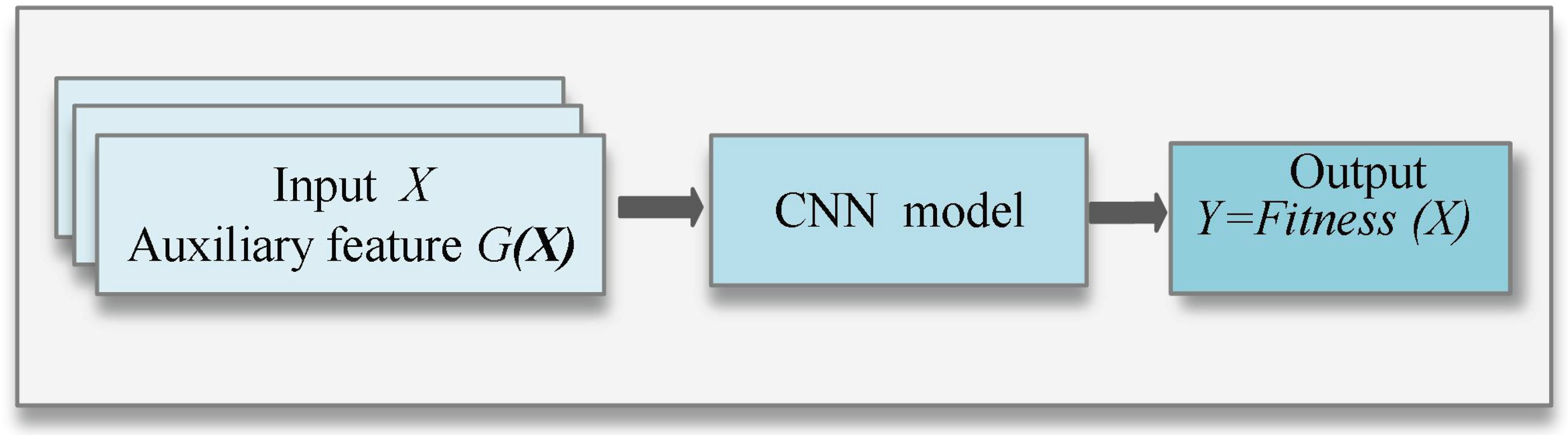

- (1)

- The input feature vector and auxiliary feature

- (2)

- The three-dimensional out features

3.3. Test Case Generation Using MF_CNNpro Model and PSO

3.3.1. Selecting Excellent Initial Particles via MF_CNNpro Model

3.3.2. Test Case Generation for Paths Using PSO

| Algorithm 3 Test Case Generation using MF_CNNpro and PSO |

| Input: Cluster set ; MF_CNNpro model; maximum number of iterations g for particle swarm update. Output: Generated test case set for each cluster.

|

4. Example Analysis

4.1. Research Questions

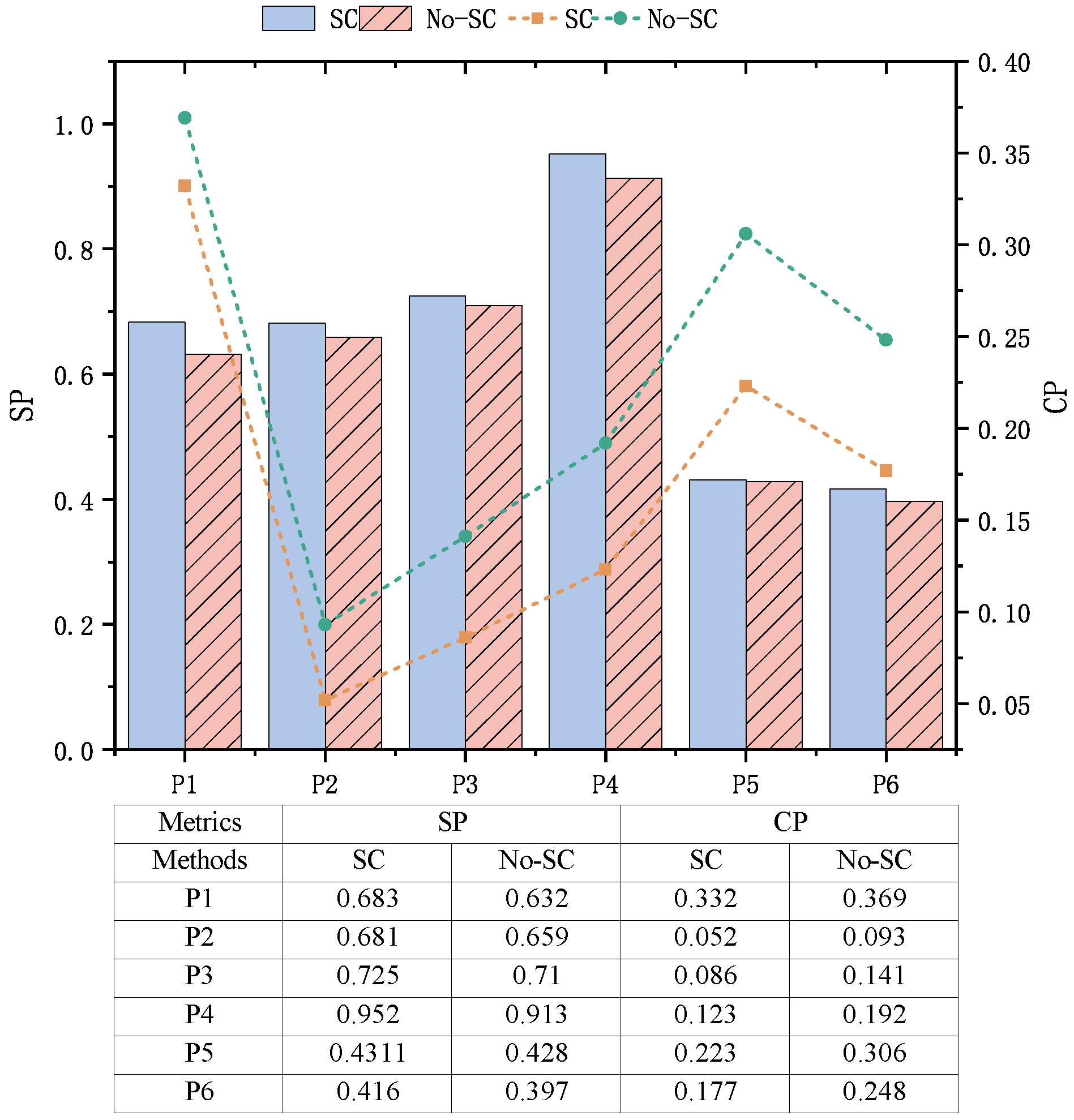

- RQ1: Does fuzzy clustering help bolstering the effectiveness of mutation testing?It is not surprising that one path may resemble paths from different clusters. Consequently, it is natural to consider fuzzy clustering when dividing the path set into distinct groups. In this study, we investigate whether and to what extent the overlap among different clusters, an expected outcome of fuzzy clustering, impacts the effectiveness of mutation testing.

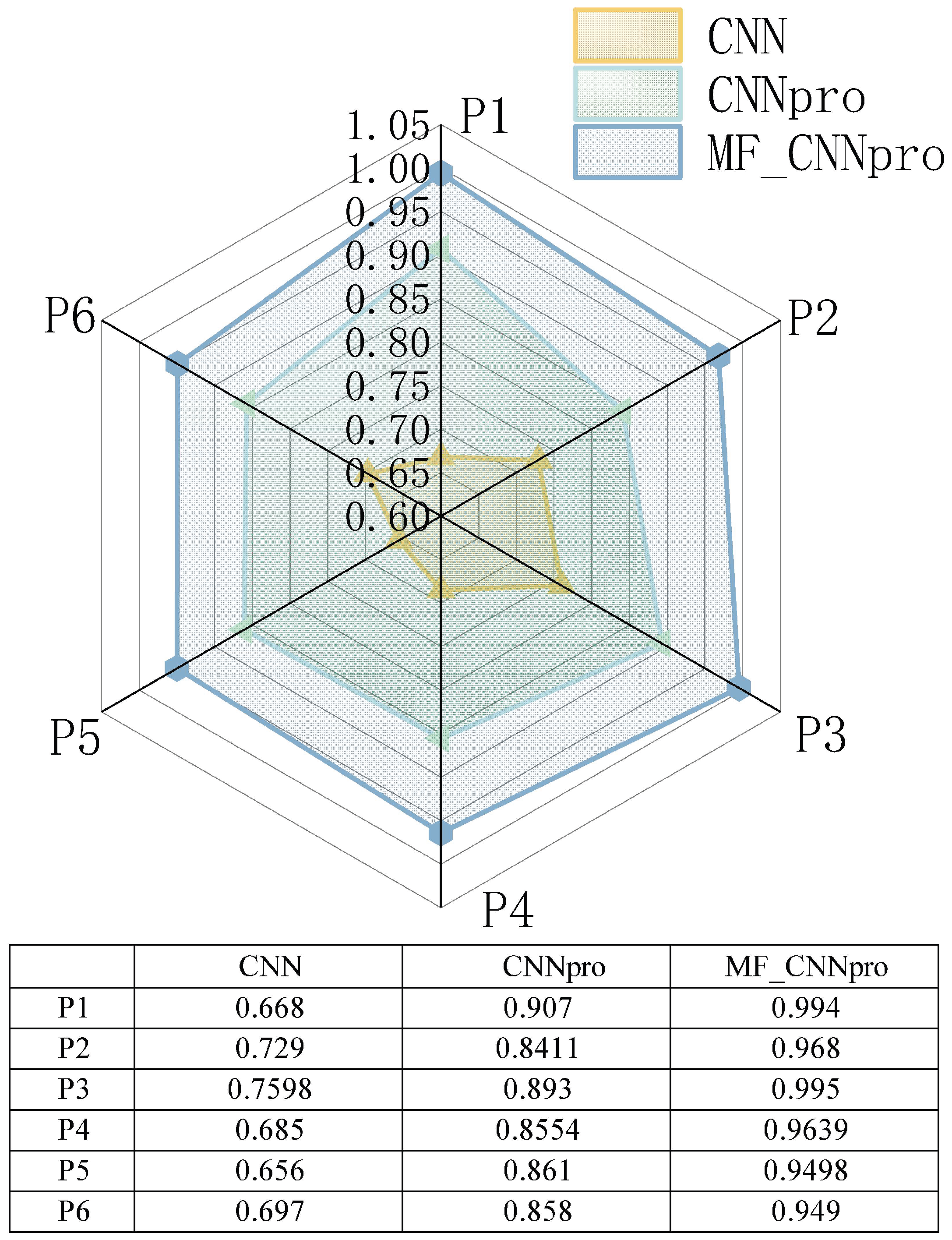

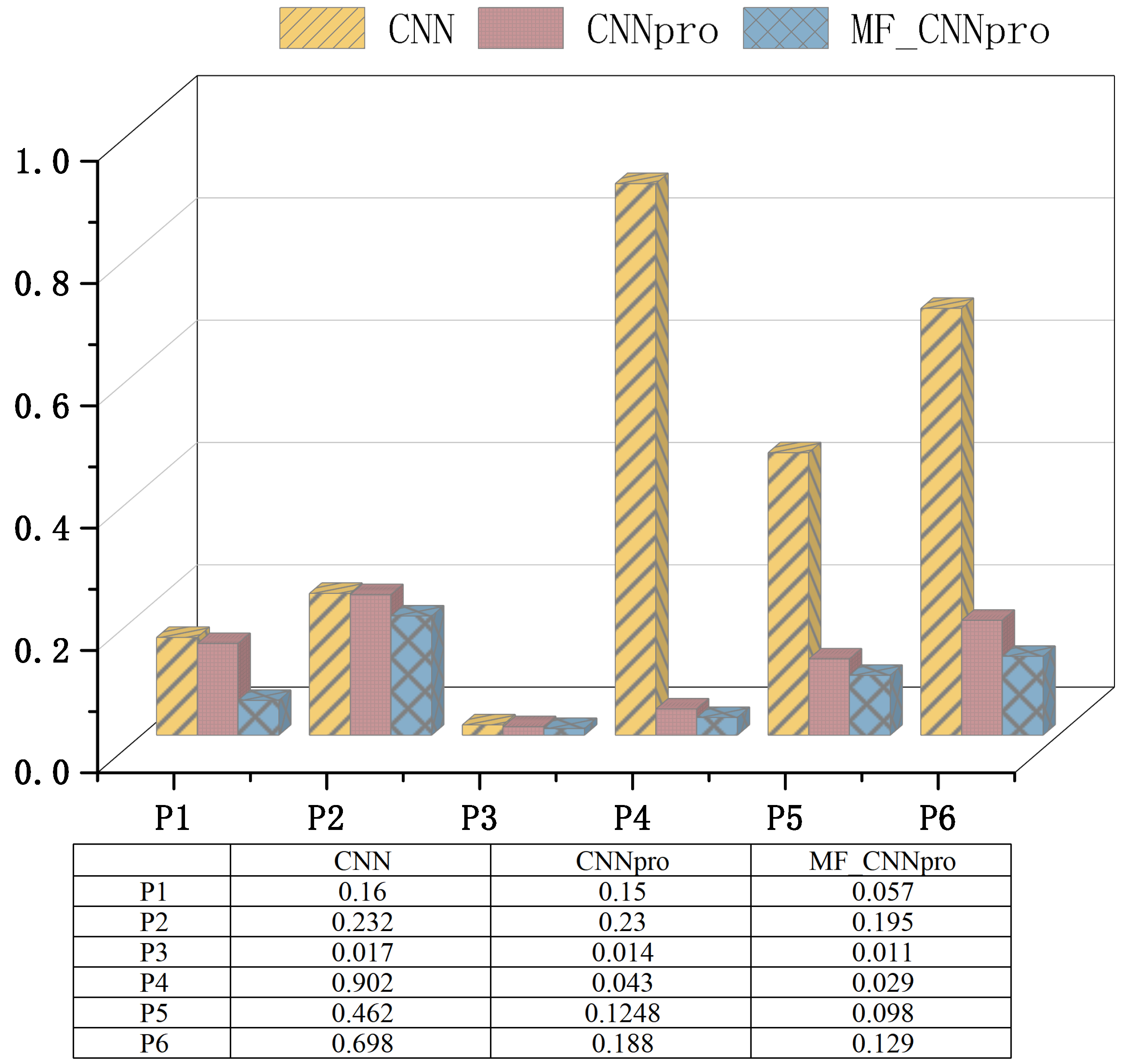

- RQ2: What is the performance of the improved models (CNNpro)?To solve the problem that evolutionary algorithms face in achieving path coverage, predictive models are built. Then, to test if the basic CNN we chose is reasonable and works well, we compare it with four other basic prediction models. Also, to check how well our improved model (CNNpro) performs, we use four different measures. These measures help us look at different parts, like accuracy, ability to generalize, use of resources, and how fast it runs.

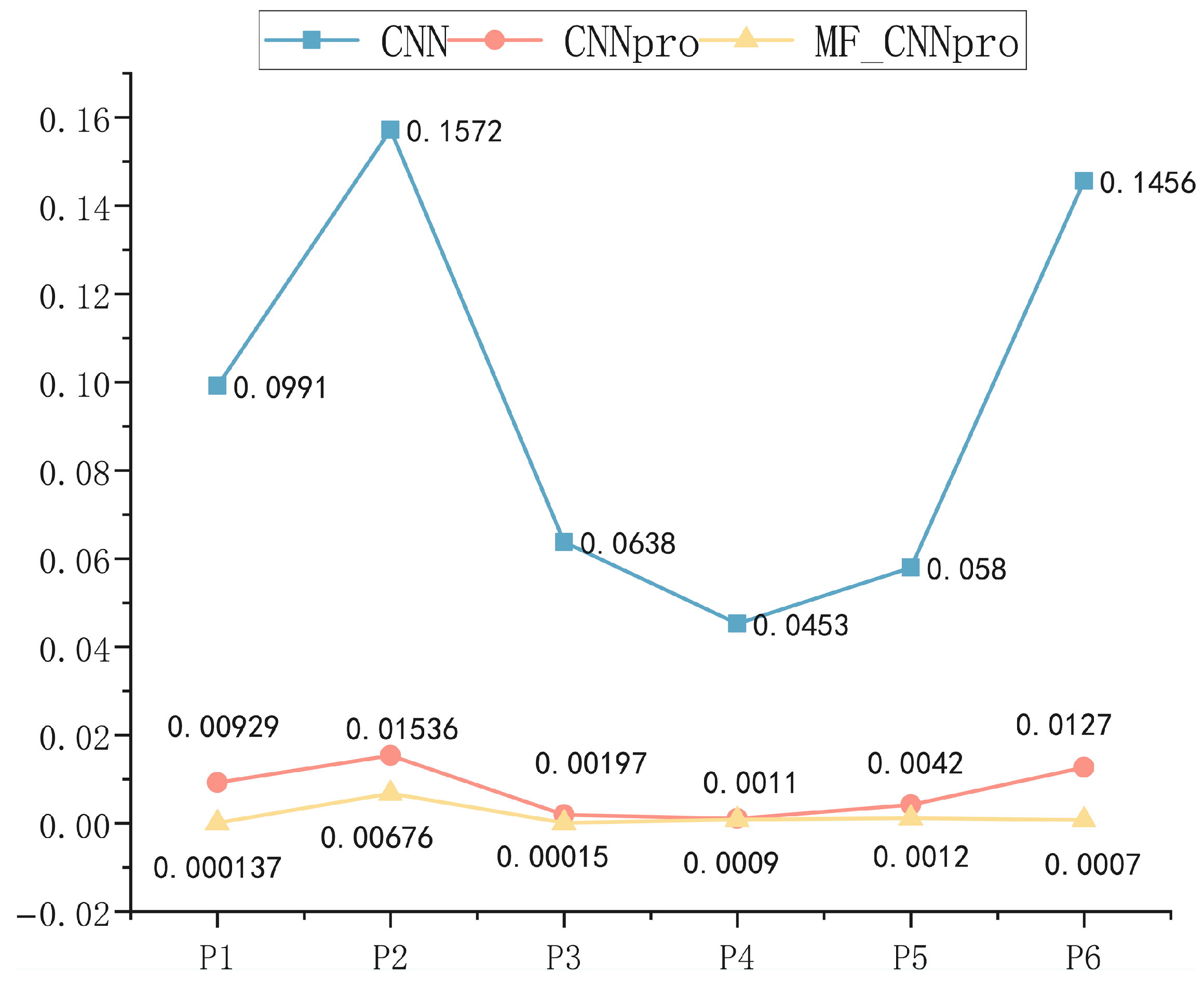

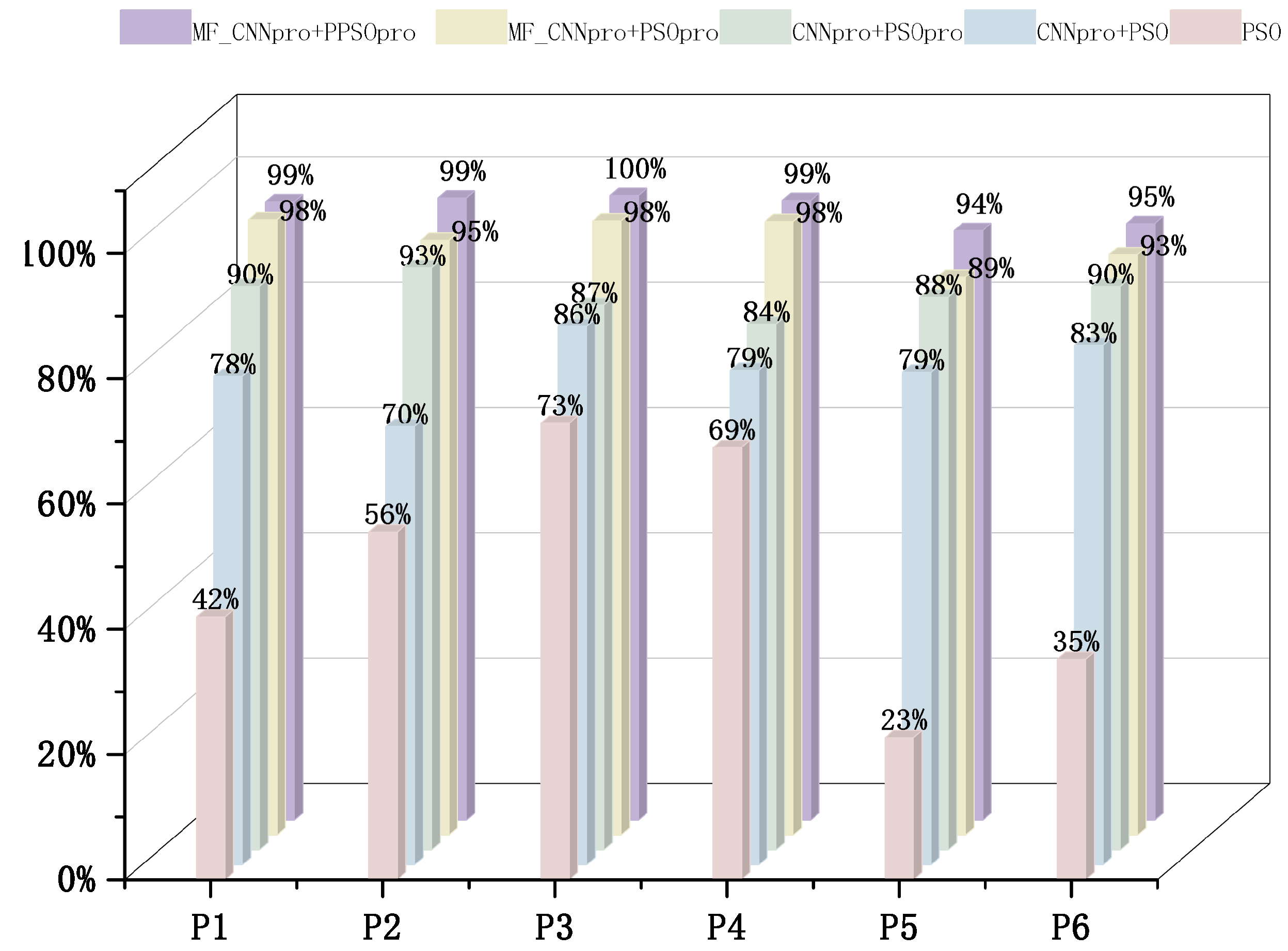

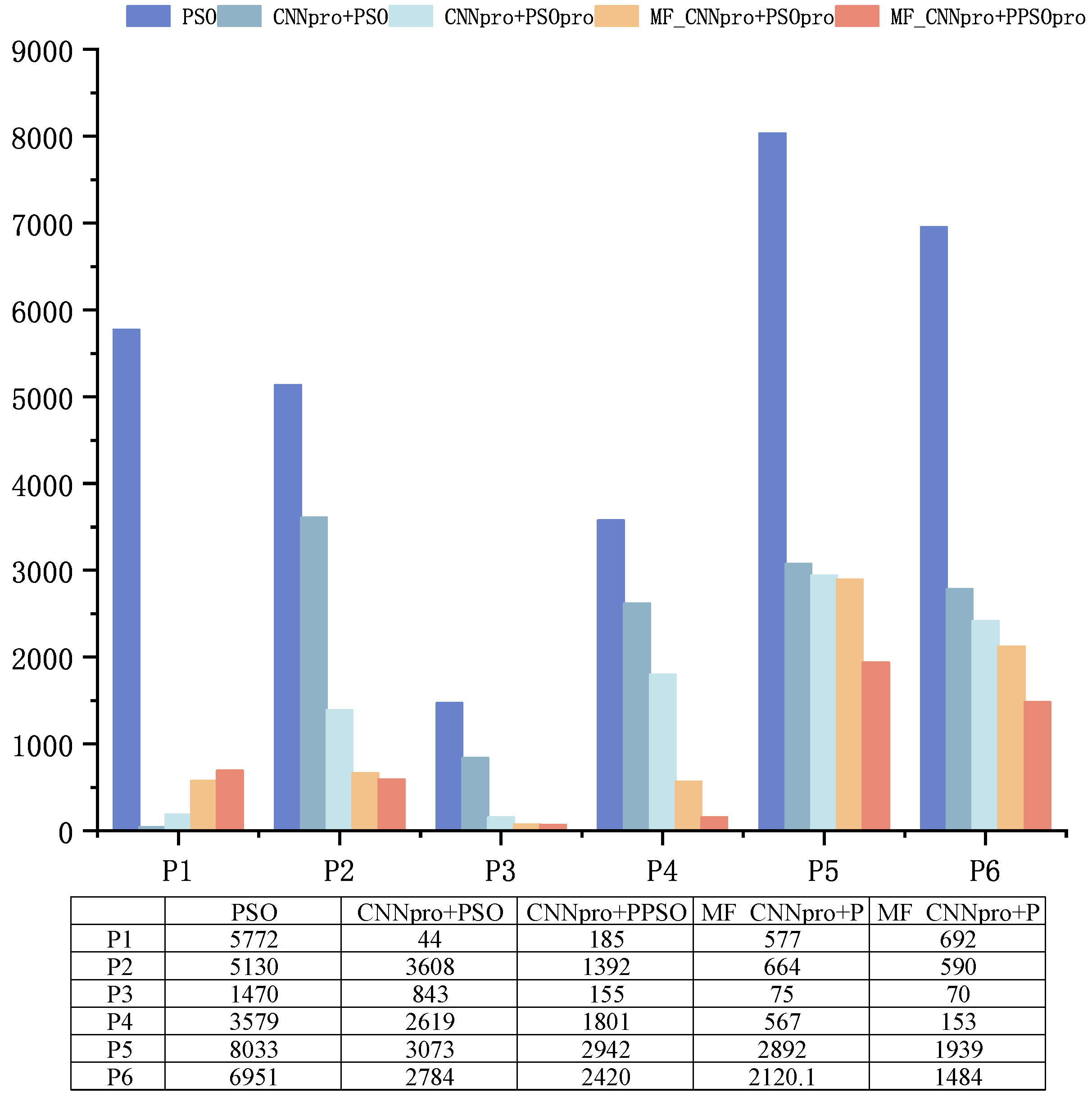

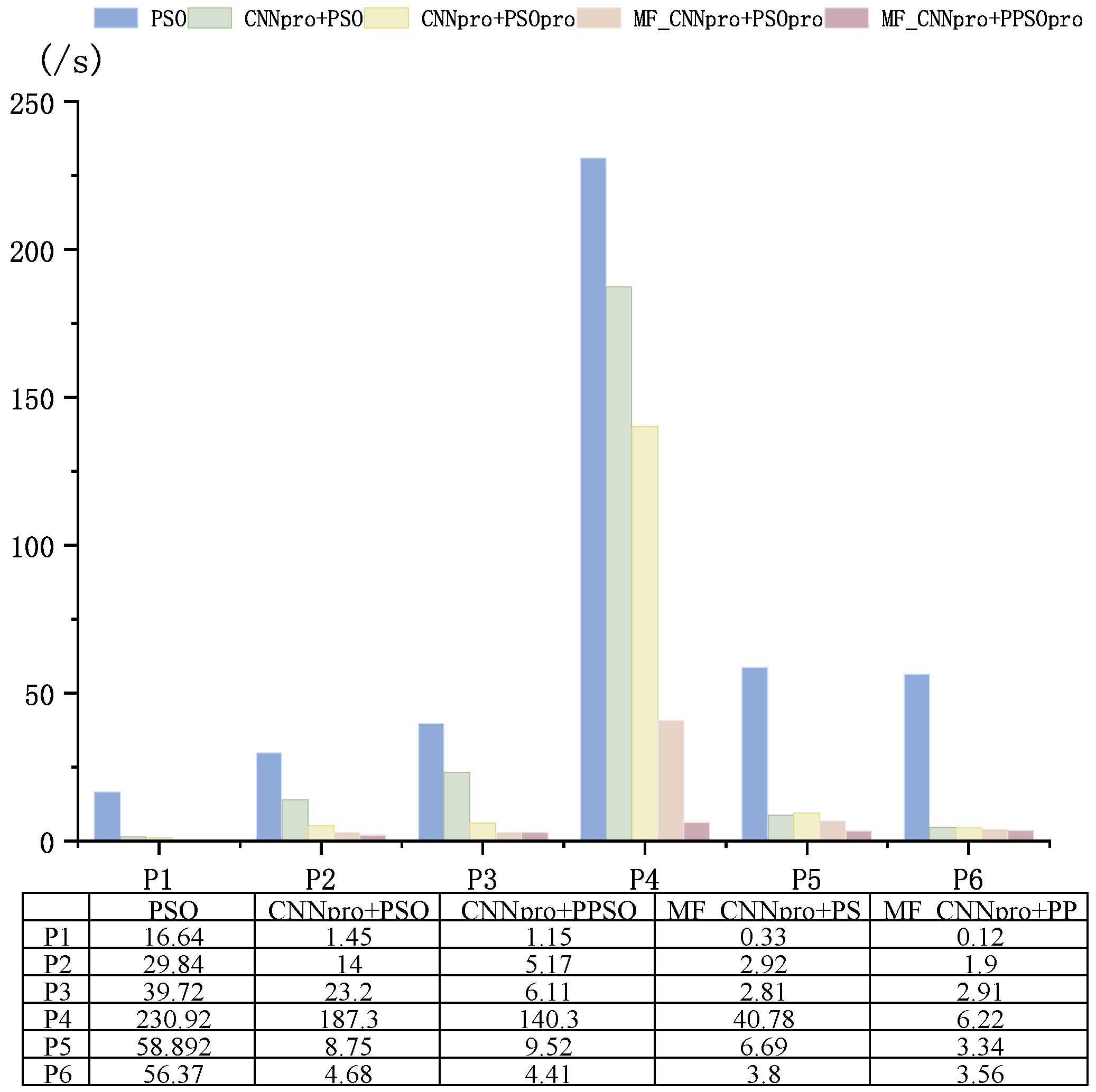

- RQ3:How does the CNNpro_PSO method improve the speed of creating test data?The improved model and the PSO method are joined together (CNNpro_PSO). This combination aims to speed up test data generation. To test its performance, we use three other methods and four metrics for comparison: success rate, iteration count, time spent, and mutation score. Finally, we run hypothesis tests on the results to show our method’s importance.

4.2. Experiment Settings

4.2.1. Procedure for RQ1

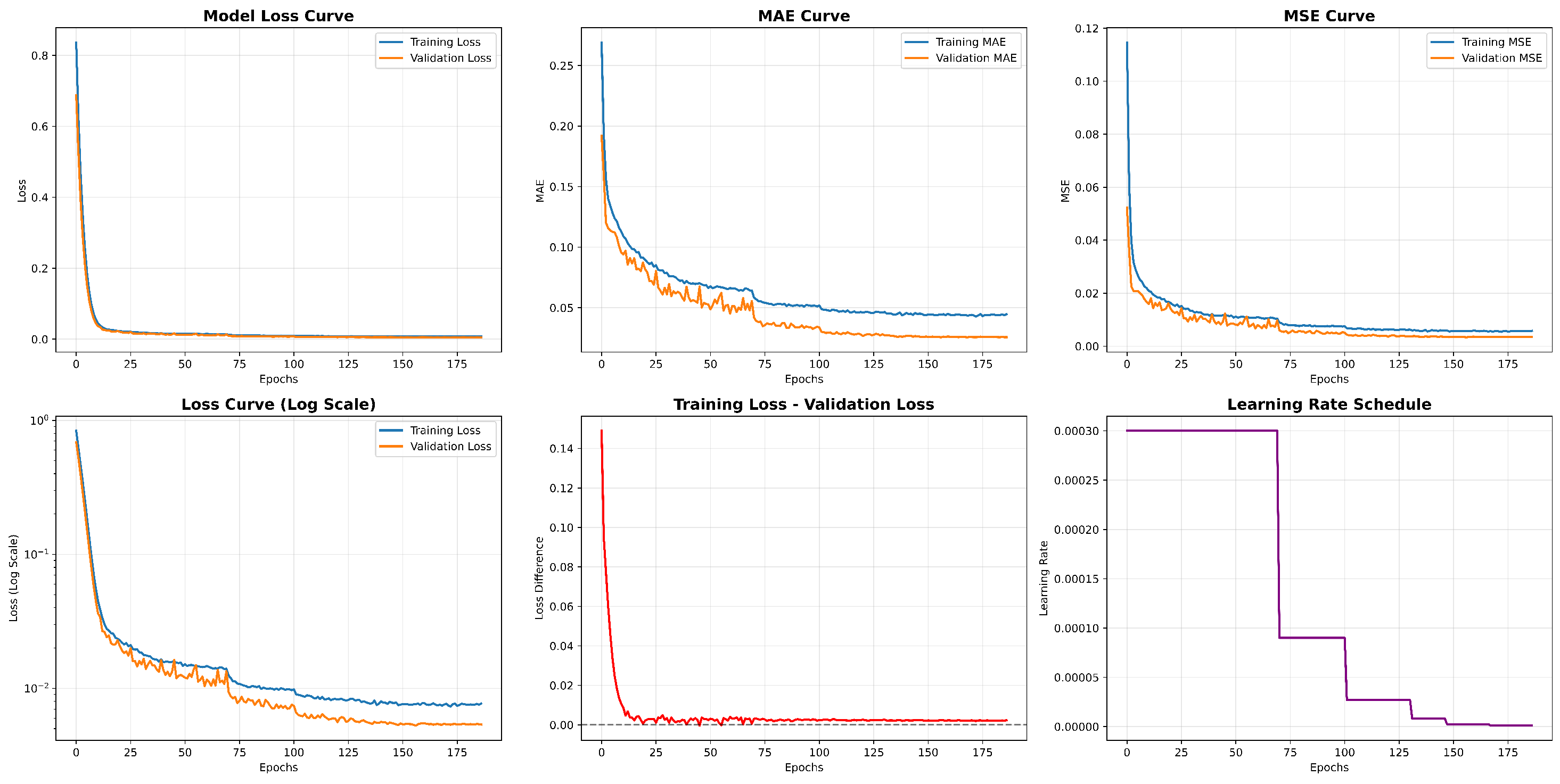

4.2.2. Procedure for RQ2

- Index Agreement (): It is used to measure the consistency between the predicted values and the true values.

- U-statistic: This metric tests for model bias by focus on measuring error in prediction between the predicted and true values, which helps find systematic errors and ensures the model is fair. A U-statistic closer to 0 indicates higher accuracy.

- Mean Squared Error (): It evaluates the average magnitude of errors in the model’s predictions by calculating the squared differences between predicted and actual values.

- The Memory Consumption (): It measures the memory used by the prediction model when it runs. Memory use is important because it shows how complex the model is and how much computing power it needs. A lower MiB value means the model uses less memory, so it is more lightweight and efficient. This is very important when working with large datasets.

4.2.3. Procedure for RQ3

4.3. Experimental Process

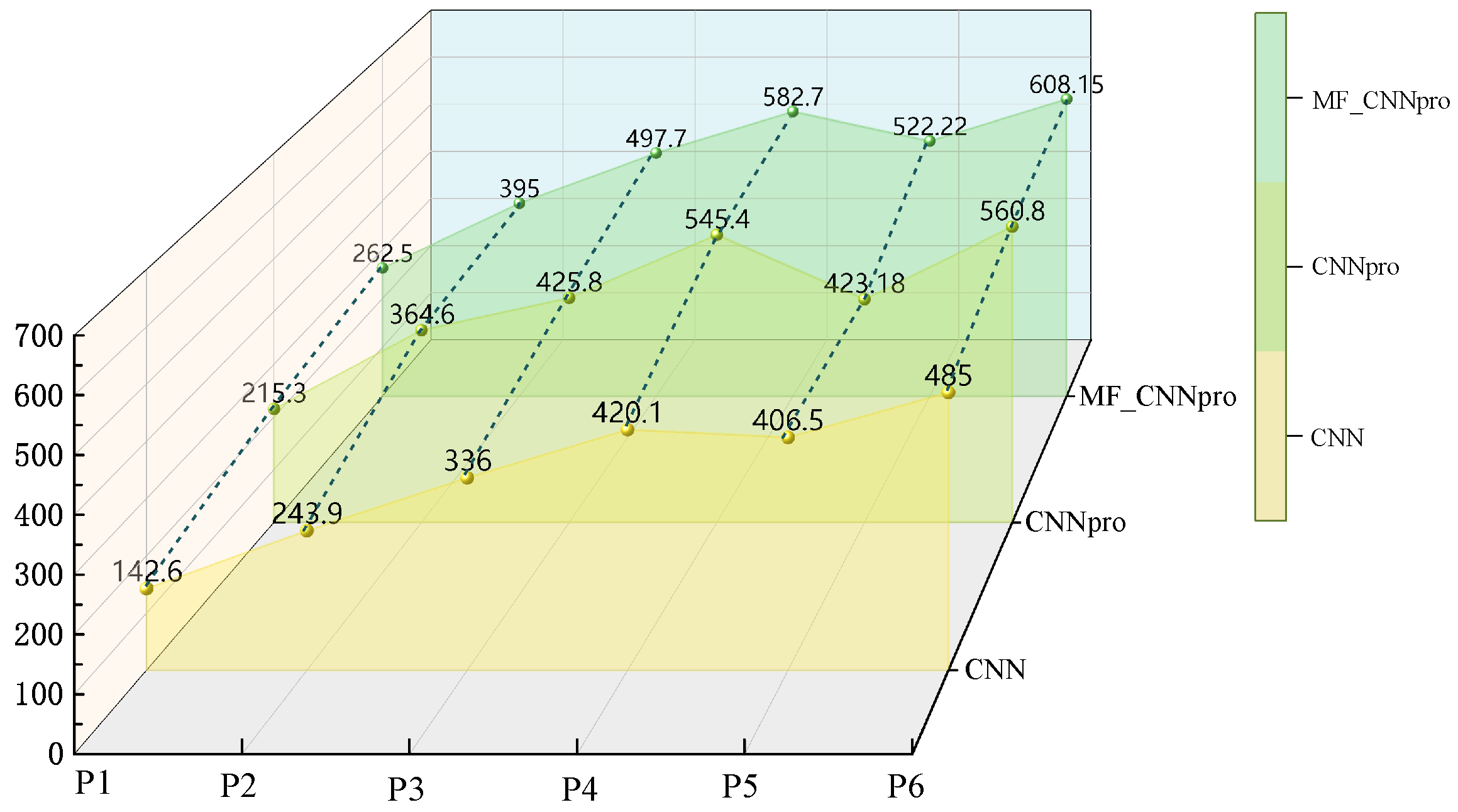

4.3.1. Answer to RQ1

4.3.2. Answer to RQ2

4.3.3. Answer to RQ3

5. Complexity and Limitations

5.1. Complexity

Fuzzy Clustering of Mutation Paths

- c is the number of clusters (determined by the threshold U, which is far smaller than the total number of paths n);

- ite is the number of iterations.

5.2. MF_CNNpro Model Construction Stage

- k is the number of training epochs (usually set between 10–30, a small constant);

- s is the parameter size of the MF_CNNpro model (the CNN architecture is fixed, so s is a constant).

5.3. Test Case Generation Stage (MF_CNNpro + PSO)

5.4. Limitations

5.4.1. Dependency on Clustering Threshold in Specific Scenarios

5.4.2. Sensitivity to Cluster Size in Model Construction

5.4.3. Lack of Cross-Cluster Collaboration

6. Related Work

6.1. Mutation Testing

6.2. Test Case Generation Based on Evolutionary Algorithms

6.3. Surrogate Model-Based Software Testing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papadakis, M.; Kintis, M.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Le Traon, Y.; Harman, M. Mutation testing advances: An analysis and survey. Adv. Comput. 2019, 112, 275–378. [Google Scholar]

- Kintis, M.; Papadakis, M.; Papadopoulos, A. How effective are mutation testing tools?—An empirical analysis of Java mutation testing tools with manual analysis and real faults. In Empirical Software Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tufano, M.; Watson, C.; Bavota, G.; Penta, M.D.; White, M.; Poshyvanyk, D. Learning how to mutate source code from bug-fixes. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME), Cleveland, OH, USA, 29 September–4 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, A.; Jovanovic, L.; Bacanin, N.; Antonijevic, M.; Savanovic, N.; Zivkovic, M.; Milovanovic, M.; Gajic, V. Exploring metaheuristic optimized machine learning for software defect detection on natural language and classical datasets. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-W.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, K.-Q. Test case generation for multiple paths based on PSO algorithm with metamorphic relations. IET Softw. 2018, 12, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, G.; Untch, R.H.; Chu, C.; Harrold, M.J. Prioritizing test cases for regression testing. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2001, 27, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; West, M.; Escalona, A.; Liu, X. Mutation testing in practice using ruby. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Eighth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW), Graz, Austria, 13–17 April 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan, J.R.; Mathur, A.P. Weak mutation is probably strong mutation. In Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, Technical Report SERC-TR-83-P; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Howden, W.E. Weak mutation testing and completeness of test sets. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1982, 8, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, M.; Malevris, N. Automatically performing weak mutation with the aid of symbolic execution, concolic testing and search-based testing. Softw. Qual. J. 2011, 19, 691–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-J.; Gong, D.-W.; Yao, X.-J. Mutation testing based on statistical dominance analysis. Ruan Jian Xue Bao/Journal Softw. 2015, 26, 2504–2520. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dang, X.-Y.; Li, J.-J.; Nie, C.-H.; Xu, B.-W. Test data generation for covering mutation-based path using MGA for MPI program. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 210, 111962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Dang, X.-Y.; Nie, C.-H.; Xu, B.-W. Optimizing test data generation using SI_CNNpro-enhanced MGA for mutation testing. J. Syst. Softw. 2025, 230, 112517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhlif, M.; Hanine, M.; Kharmoum, N. A decade of intelligent software testing research: A bibliometric analysis. Electronics 2023, 12, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojdanić, M.; Ma, W.; Laurent, T.; Papadakis, M. On the use of commit-relevant mutants. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2022, 27, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, R.; Kennedy, J.; Blackwell, T. Particle swarm optimization: An overview. Swarm Intell. 2007, 1, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hla, K.H.S.; Choi, Y.; Park, J.S. Applying particle swarm optimization to prioritizing test cases for embedded real time software retesting. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE 8th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology Workshops, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 8–11 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Allawi, H.M. A greedy particle swarm optimization (GPSO) algorithm for testing real-world smart card applications. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 2020, 22, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-Q.; Wang, W.-W.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, R.-L. Weak mutation test case set generation based on dynamic set evolutionary algorithm. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 37, 2659–2664. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, M. Search based software testing for Android. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 10th International Workshop on Search-Based Software Testing (SBST), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–23 May 2017; IEEE/ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- López-Martín, C. Machine learning techniques for software testing effort prediction. Softw. Qual. J. 2022, 30, 65–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, O.; Gunes, B.; Chen, T.-Y.; Khatiri, S. Empirically evaluating flaky test detection techniques combining test case rerunning and machine learning models. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2023, 28, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S. Optimal harvesting for a logistic growth model with predation and a constant elasticity of variance. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 260, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.-W.; Sun, B.; Yao, X.-J.; Tian, T. Test Data Generation for Path Coverage of MPI Programs Using SAEO. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 30, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Wong, T.T. Testing Deep Learning Models: A First Comparative Study of Multiple Testing Techniques. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.-J.; Gong, D.-W.; Li, B. Evolutional test data generation for path coverage by integrating neural network. Ruan Jian Xue Bao/Journal Softw. 2016, 27, 828–838. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Lu, M.; Xu, B.; Gao, H. An Improved CNN Model for Within-Project Software Defect Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, C.; Zhu, W. Module-Aware Optimization for Auxiliary Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Offutt, A.J.; Lee, A.; Rothermel, G. An experimental determination of sufficient mutant operators. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 1996, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugazhenthi, A.; Kumar, L.S. Selection of optimal number of clusters and centroids for k-means and fuzzy c-means clustering: A review. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS), Patna, India, 14–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oskouei, A.G.; Samadi, N.; Khezri, S.; Moghaddam, A.N.; Babaei, H.; Hamini, K.; Nojavan, S.F.; Bouyer, A.; Arasteh, B. Feature-weighted fuzzy clustering methods: An experimental review. Neurocomputing 2025, 619, 129176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-W. Mutation testing cost reduction by clustering overlapped mutants. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 115, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.B.; Parejo, J.A.; Segura, S.; Durán, A.; Papadakis, M. Mutation Testing in Practice: Insights From Open-Source Software Developers. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2024, 50, 1130–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.R.S.; Brito, M.A.S.; Silva, R.A.; Souza, P.S.L.; Zaluska, E. Research in concurrent software testing. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Systems Testing, Analysis, and Debugging (PADTAD ’11), Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–21 July 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, X.; Gong, D.; Yao, X.; Tian, T.; Liu, H. Enhancement of mutation testing via fuzzy clustering and multi-population genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlet, R.G. Testing programs with the aid of a compiler. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1977, 3, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMillo, R.A.; Lipton, R.J.; Sayward, F.G. Hints on test data selection: Help for the practicing programmer. Computer 1978, 11, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Mutation-based data augmentation for software defect prediction. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2024, 36, e2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekam, T.T.; Papadakis, M.; Le Traon, Y.; Harman, M. An empirical study on mutation, statement and branch coverage fault revelation that avoids the unreliable clean program assumption. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 20–28 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Derezinska, A.; Kowalski, K. Object-oriented mutation applied in common intermediate language programs originated from C. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops, Berlin, Germany, 21–25 March 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Harman, M. An analysis and survey of the development of mutation testing. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2010, 37, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, M.; Agrawal, R. Mutation Testing and Test Data Generation Approaches: A Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Trends for Information Technology and Computer Communications, Singapore, 6–7 August 2016; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.-J.; Gong, D.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L. Orderly generation of test data via sorting mutant branches based on their dominance degrees for weak mutation testing. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2020, 48, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gu, Q. Mutation testing: Principal, optimization and application. J. Front. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 1057–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Offutt, A.J.; Lee, S.D. How strong is weak mutation? In Proceedings of the Symposium on Testing, Analysis, and Verification; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.M.J.; Arasteh, B.; Isazadeh, A.; Mohabbati, B. An error-propagation aware method to reduce the software mutation cost using genetic algorithm. Data Technol. Appl. 2021, 55, 118–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod Chandra, S.S.; Anand, H.S. Nature inspired meta heuristic algorithms for optimization problems. Computing 2022, 104, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, F.; Anwer, F. A systematic literature review on software security testing using metaheuristics. Autom. Softw. Eng. 2024, 31, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.B.; Acharya, A.A.; Mishra, R. Evolutionary algorithms for path coverage test data generation and optimization: A review. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2019, 15, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.; Babar, M.I.; Butt, R.; Khan, S. An optimized test case minimization technique using genetic algorithm for regression testing. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 6789–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.-J.; Gong, D.-W.; Li, B.; Tian, T. Testing method for software with randomness using genetic algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 61999–62010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.A.; Akila, C.; Raja, S.P. Guided Intelligent Hyper-Heuristic Algorithm for Critical Software Application Testing Satisfying Multiple Coverage Criteria. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2024, 33, 2450029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Gong, D.-W.; Tian, T.; Yao, X.-J. Integrating an ensemble surrogate model’s estimation into test data generation. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2020, 48, 1336–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalfitano, D.; Fasolino, A.R.; Tramontana, P. Artificial intelligence applied to software testing: A tertiary study. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Eleneen, A.; Palliyali, A.; Catal, C. The role of Reinforcement Learning in software testing. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2023, 164, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input X | Predicted Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.26 | ||

| 1.43 | ||

| 0.67 | ||

| 1.1 | ||

| 0.11 |

| Input X | Predicted Value | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.42 | ||

| 0.32 | ||

| 0.37 | ||

| 0.35 | ||

| 0.37 |

| ID | Program | Lines | Statement Under Test | Function | Non-Equivalent Mutant | Paths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Triangle | 26 | 17 | Triangle Classification | 34 | 9 |

| P2 | Cal | 68 | 22 | Date Calc | 44 | 9 |

| P3 | Number | 276 | 72 | Data Analysis | 142 | 24 |

| P4 | Energy | 2312 | 112 | Energy Analysis | 330 | 34 |

| P5 | Supply | 9533 | 206 | Material Flow | 1030 | 113 |

| P6 | monitor | 11,935 | 320 | System Monitoring | 1640 | 136 |

| ID | SC (%) | NO-SC (%) | Clustering Rate Difference (pp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 22.00 | 24.32 | −2.32 |

| P2 | 55.56 | 58.00 | −2.44 |

| P3 | 50.00 | 54.10 | −4.10 |

| P4 | 19.41 | 22.90 | −3.49 |

| P5 | 16.78 | 27.78 | −11.00 |

| P6 | 15.38 | 20.00 | −4.62 |

| Avg | 29.86 | 34.52 | −4.66 |

| Iterations | Execution Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF_CNNpro+PSOpro vs. PSO(%) | MF_CNNpro+PPSOpro vs. PSO(%) | MF_CNNpro+PSOpro vs. PSO(%) | MF_CNNpro+PPSOpro vs. PSO(%) | |

| p1 | 91.40 | 93.73 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| p2 | 86.20 | 87.70 | 91.32 | 93.28 |

| p3 | 73.53 | 76.47 | 82.35 | 94.12 |

| p4 | 98.60 | 95.81 | 96.10 | 97.60 |

| p5 | 83.50 | 89.32 | 89.50 | 93.71 |

| p6 | 87.30 | 91.15 | 90.60 | 94.68 |

| Ave. | 86.75 | 89.03 | 91.65 | 95.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qu, Q.; Dang, X.; Xia, H.; Tao, L. Efficient Multiple Path Coverage in Mutation Testing with Fuzzy Clustering-Integrated MF_CNNpro_PSO. Mathematics 2026, 14, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010047

Qu Q, Dang X, Xia H, Tao L. Efficient Multiple Path Coverage in Mutation Testing with Fuzzy Clustering-Integrated MF_CNNpro_PSO. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Qian, Xiangying Dang, Heng Xia, and Lei Tao. 2026. "Efficient Multiple Path Coverage in Mutation Testing with Fuzzy Clustering-Integrated MF_CNNpro_PSO" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010047

APA StyleQu, Q., Dang, X., Xia, H., & Tao, L. (2026). Efficient Multiple Path Coverage in Mutation Testing with Fuzzy Clustering-Integrated MF_CNNpro_PSO. Mathematics, 14(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010047