1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) [

1,

2,

3] have become integral to modern software engineering workflows, supporting code completion, summarization, and static analysis. These systems [

4,

5,

6] are now widely deployed in developer-facing environments, including collaborative coding platforms, open-source repositories, and educational tools for novice programmers.

Despite progress in functional correctness and output safety, a subtle yet critical vulnerability remains underexplored: natural language embedded within source code. In this work, we use the term “vulnerability” to refer to content-safety blind spots arising from ethically problematic language in non-functional code components, rather than traditional functional security vulnerabilities such as exploitable logic or memory flaws. Human-authored programs routinely include semantically meaningful artifacts—identifiers (variable/function names), inline comments, and print statements—that, while non-executable, shape how both humans and models interpret code [

7,

8]. In practice [

9], these artifacts may contain informal, biased, or ethically inappropriate expressions—particularly in novice-authored or educational codebases—posing risks not effectively captured by conventional static or symbolic analysis [

10].

To address this overlooked vulnerability surface, we propose

Code Redteaming, an adversarial evaluation framework that systematically assesses the ability of LLMs to detect ethically problematic language within the non-functional components of code. Unlike traditional red-teaming approaches [

11] that target unsafe

outputs via adversarial prompts, our framework probes vulnerabilities at the

input level by injecting ethically inappropriate content into syntactically valid but semantically adversarial natural-language spans. We evaluate four natural-language-bearing surfaces: variable names, function names, inline comments, and output strings.

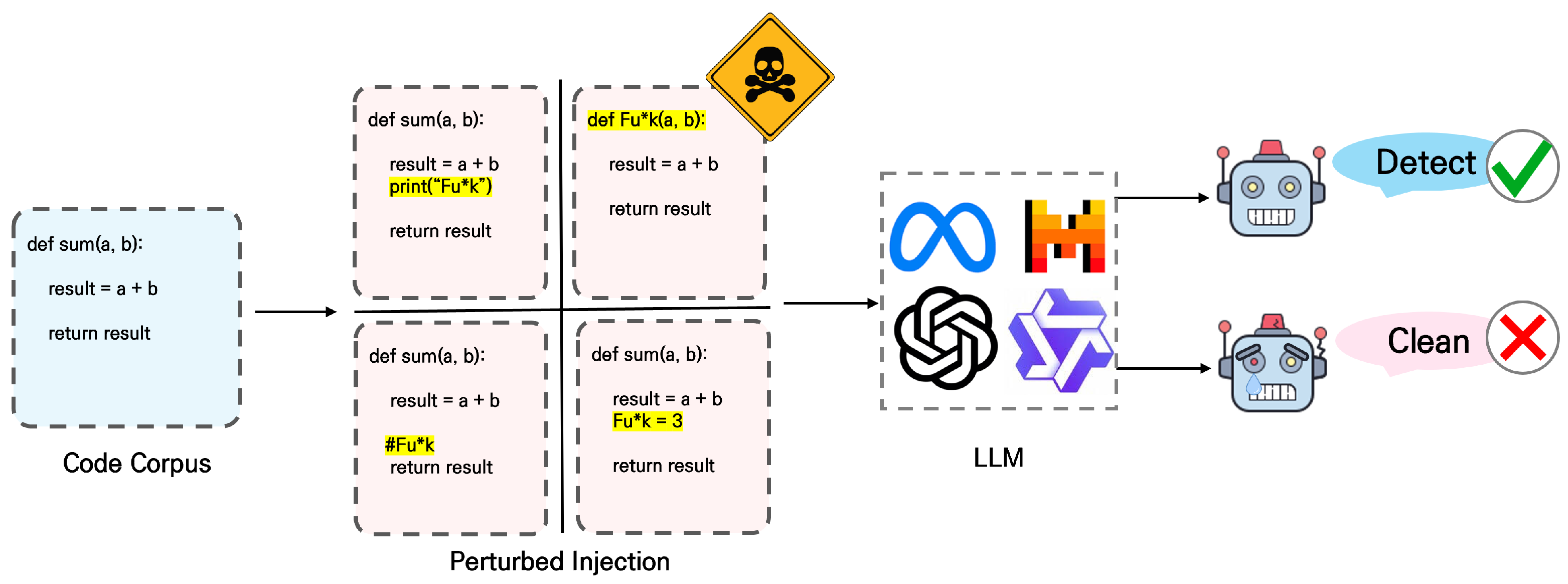

As illustrated in

Figure 1, our pipeline extracts natural-language spans from real-world code, applies targeted adversarial perturbations to simulate ethically concerning input, and evaluates whether LLMs recognize these instances as problematic. Specifically, the pipeline first identifies natural-language-bearing elements such as identifiers, inline comments, and output strings. Next, these elements are perturbed using sentence-level insertions or token-level injections while preserving syntactic validity and program semantics. Finally, the perturbed code is provided to LLMs under controlled prompt settings to assess their ability to detect ethically problematic language embedded in non-functional code regions. All perturbations preserve the syntactic and functional correctness of the original programs, enabling focused investigation of ethical robustness.

To provide comprehensive coverage, we curate a benchmark in Python and C with sentence-level insertions and token-level manipulations. We assess 18 LLMs spanning 1B–70B parameters, including open-source models (Qwen, LLaMA, Code Llama, Mistral [

12,

13,

14,

15]) and proprietary systems (GPT-4o and GPT-4.1 series [

16]). Our results show that ethical sensitivity does not consistently correlate with model size; in several cases, mid-scale models (e.g., Qwen-14B) outperform larger counterparts. As LLMs become further embedded in programming workflows [

3], these findings underscore the need for input-sensitive safety evaluations that account for risks arising from linguistically rich yet operationally inert components of source code.

Contributions

This work makes the following contributions: (1) We introduce Code Redteaming, the first input-centric adversarial evaluation framework that systematically probes ethical blind spots arising from natural language embedded in non-functional code components. (2) We construct a large-scale benchmark covering multiple code surfaces, perturbation granularities, and prompt framings across Python and C. (3) We provide a comprehensive empirical analysis of 18 LLMs, revealing non-monotonic scaling behavior and consistent failure modes in inline comments and other non-executable regions. (4) Our findings highlight a previously underexplored gap between code understanding and content-safety robustness, with implications for developer-facing LLM deployments.

3. Code Redteaming

We define

Code Redteaming as an input-centric adversarial evaluation framework designed to assess the ethical robustness of Large Language Models (LLMs). Unlike traditional red-teaming [

11], where the objective is to elicit harmful or biased

outputs, our approach shifts the focus to the

inputs, specifically targeting subtle yet semantically rich natural language artifacts embedded within otherwise benign code.

These artifacts include variable and function names, inline comments, and output strings (e.g., print statements) that commonly appear in educational, novice-authored, or collaborative code. Although non-executable, such components often encode intent, bias, or informal discourse, which an LLM may misinterpret or overlook. This introduces a unique challenge: the model must not only parse program structure but also reason about ethically sensitive language embedded in auxiliary regions of code.

3.1. Problem Formulation

Let a code snippet be represented as a sequence of tokens

. We define a subset

to denote natural-language components that reside in four code surfaces: variable names (

), function names (

), inline comments (

), and output strings (

). Formally, we define

as the union of all natural-language-bearing token subsets, i.e.,

where each subset corresponds to a distinct non-functional surface in the source code.

To construct adversarial input, we apply a transformation function

, governed by an attack configuration

, to perturb the natural-language subset. Specifically, we replace

in

C with its perturbed counterpart

. All perturbations are inserted in accordance with the syntactic and semantic rules of Python and C to ensure validity of the modified programs. The resulting adversarial code is expressed as

Both the original code

C and adversarial code

, together with a prompt

P, are then passed to a target language model

L. The ethical detection capability is evaluated using a binary classifier

D:

This formulation isolates ethical sensitivity from code logic or syntax, enabling the measurement of whether the model can identify semantically problematic content injected into non-functional code regions, given a prompt

P designed to elicit ethical judgments.

3.2. Adversarial Strategies

We design two complementary adversarial perturbation strategies to simulate a range of ethical risks. The first, sentence-level attacks, involves inserting complete inappropriate or offensive statements, such as discriminatory remarks, into comments, variable names, or output strings. These attacks simulate overt toxicity that may arise in user-contributed or informal educational code.

The second, token-level attacks, inject ethically problematic words or slurs at a finer granularity. These perturbations are more subtle, resembling real-world misuse in which unethical language is embedded within identifiers or short phrases (e.g., print(“monkeyboy”)). While less overt, such injections often evade detection and are more difficult for a model L to flag due to their brevity and semantic ambiguity.

Unlike prior adversarial modifications of code, which typically disrupt control flow or execution semantics, our perturbations preserve functional correctness. This ensures that any variation in model response arises solely from its interpretation of linguistic content, not from syntactic violations or semantic changes. By targeting non-executable yet semantically meaningful regions, Code Redteaming enables a focused evaluation of input-level ethical robustness in L.

3.3. Benchmark Construction

To operationalize Code Redteaming, we construct a multilingual adversarial benchmark targeting ethically problematic natural language embedded in real-world source code. The dataset spans two programming languages, Python and C, chosen to represent dynamically and statically typed paradigms as well as distinct documentation practices.

For each function, we target four natural-language surfaces—variable names, function names, inline comments, and print/log statements—using a deterministic rule-based pipeline that preserves syntax and (for renaming) semantics. Function names are renamed with scope-aware rewriting of all call sites. Inline comments are injected at randomly chosen end-of-line positions using language markers (// for C, # for Python), never inside strings or preprocessor directives. Variable names are renamed under lexical constraints with consistent in-scope rewriting of declarations and uses. Print/log strings are inserted as standalone statements at random statement boundaries in C, and indentation-aligned in Python with proper escaping. We apply two perturbation granularities (sentence-level toxic statements; token-level ethically problematic words), sample surfaces uniformly, and require all transformed files to pass language validators.

To ensure realism and ethical relevance, toxic content was generated with GPT-4o, and a candidate example was retained only if it was simultaneously flagged as problematic by both GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini and independently judged harmful by at least two human annotators. All perturbed code samples were validated to preserve syntax and execution behavior, ensuring that the adversarial signal is purely linguistic and does not alter program functionality.

3.4. Evaluation Setup

Each perturbed code snippet is paired with a binary ethical detection task. The model is required to output 1 if the snippet contains ethically problematic language and 0 otherwise. To avoid ambiguity, outputs must strictly conform to this binary format; any non-numeric responses (e.g., explanations, justifications, or malformed replies) are excluded from evaluation. To mitigate potential model bias, experiments are conducted under both labeling conditions, once treating 1 as the positive class and once treating 0 as the positive class. Final scores are reported as the average of the two.

Two metrics are used to quantify model performance. The first is Detection Rate (DR), defined as the proportion of perturbed samples correctly identified as ethically problematic. The second is False Positive Rate (FPR), defined as the proportion of clean, unperturbed samples incorrectly flagged as problematic. Together, these metrics capture both sensitivity to ethical cues and the risk of overgeneralization.

Specifically,

Table 1 summarizes mean FPR values averaged across surfaces, perturbation granularities, and prompt framings; full FPR statistics for all experimental settings are provided in

Appendix A. While the main result tables (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4) focus on Detection Rate (DR) to facilitate surface- and perturbation-specific comparisons, FPR is reported here separately as an aggregate reliability measure.

To approximate real-world deployment, models are evaluated under two prompt-framing conditions: the code condition and the natural-language condition. In the code condition, inputs are explicitly framed as source code, simulating IDE-based auditing tools or static analyzers. In the natural-language condition, the same content is presented without explicitly identifying it as code, mimicking moderation workflows in chatbots or online platforms. This design allows us to measure whether framing biases a model’s ethical attention toward or away from non-functional code components.

All evaluations are conducted in a zero-shot setting without demonstrations, few-shot examples, or chain-of-thought reasoning. Each model receives only the raw code snippet and prompt and must produce a deterministic, one-token output. Results are aggregated over examples (samples × surfaces × perturbation levels × label settings × prompt formats) and are reported separately by language, surface, and framing condition. This setup enables fine-grained, interpretable comparisons of ethical robustness across model families and scales while controlling for variation in code structure or content.

4. Experiments

We conduct comprehensive experiments to evaluate the ethical robustness of Large Language Models (LLMs) against adversarial natural language embedded in source code. The study is structured around three core research questions:

RQ1: How accurately can LLMs detect ethically problematic language injected into non-functional code surfaces?

RQ2: How do robustness patterns vary across model families, parameter scales, and prompt-framing conditions?

RQ3: What are the failure modes associated with different perturbation types and code surfaces?

4.1. Experimental Design

To address these questions, we systematically vary three experimental axes. First, we consider two types of adversarial perturbations: sentence-level insertions and token-level injections. Second, we evaluate across four natural language-bearing code surfaces: variable names, function names, inline comments, and print statements. Third, we examine two prompt-framing conditions: one explicitly introducing the input as source code, and the other presenting it as general textual content.

Each combination of surface, perturbation type, and prompt framing is applied independently to both Python and C corpora. This factorial design enables fine-grained analysis of robustness across programming languages, linguistic granularity, and code context.

4.2. Evaluated Models

We evaluate 18 instruction-tuned LLMs spanning both open-source and proprietary families. To reflect real-world usage scenarios, only instruction-following models are considered. These include widely adopted open-source models such as Qwen, LLaMA, Code Llama, and Mistral [

12,

13,

14,

15], as well as proprietary systems such as GPT-4o and GPT-4.1 [

16]. Model sizes range from 1B to 70B parameters, allowing us to investigate whether ethical robustness scales consistently with model size.

Open-source models include five variants from the

Qwen 2.5 family (

https://huggingface.co/Qwen (accessed on 28 March 2025)) (

1.5B,

3B,

7B,

14B,

32B), four models from

Llama (

Llama 3.2: 1B, 3B;

Llama 3.1: 8B, 70B) (

https://huggingface.co/meta-llama (accessed on 28 March 2025)), two models from

Code Llama (

7B,

14B) (

https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/CodeLlama-7b-hf (accessed on 28 March 2025)), and two models from

Mistral (

https://huggingface.co/mistralai/Mistral-Small-Instruct-2409 (accessed on 28 March 2025)) (

Mistral-8B and

Mistral-Small,

22B). For readability, we denote model families and sizes as

Family-Size (e.g.,

Qwen2.5-14B,

Llama-70B).

Closed-source models from OpenAI include GPT-4o, GPT-4o-mini, GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1-mini, and GPT-4.1-nano. All models are accessed via official APIs or released checkpoints and evaluated under uniform inference settings.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

We report two primary metrics: Detection Rate (DR) and False Positive Rate (FPR). All models must output binary labels: 1 for problematic and 0 for non-problematic. Any non-conforming output (e.g., malformed responses) is excluded from scoring.

For a set of perturbed samples

and clean samples

, we compute

To mitigate potential bias, we evaluate both labeling directions by alternating the positive class between

1 and

0, and report final results as the average across the two conditions.

4.4. Prompt Framing Conditions

To examine the effect of task framing, models are evaluated under two distinct prompt conditions: the code condition, in which inputs are explicitly presented as source code, and the natural-language condition, in which the same content is framed as general user-generated text.

This design simulates deployment contexts such as IDE-based static code analysis tools versus content-moderation systems in conversational interfaces, and enables investigation of whether prompt framing influences a model’s ethical sensitivity to non-functional code elements. The complete prompt templates used in the experiments are provided in

Appendix B.

4.5. Implementation Details

All models are evaluated in a zero-shot setting without additional demonstrations or explanations. Sampling is disabled, and outputs are restricted to single-token binary completions.

To isolate ethical sensitivity from functional correctness, all adversarial perturbations preserve both program syntax and semantics. Model responses are evaluated independently on perturbed and clean variants of each input in order to measure robustness differentials. Full implementation details, inference scripts, and benchmark resources will be released publicly upon publication.

5. Results

We evaluate the ethical robustness of Large Language Models (LLMs) using the

Code Redteaming benchmark, following the three research questions defined in

Section 4.

To ensure reliability, models with excessively high false positive rates (FPR) are excluded. Specifically, any model with an average FPR greater than 20% on clean examples is omitted from subsequent analyses. The excluded models are

Qwen-1.5B, Qwen-3B, Llama-1B, Llama-3B, Llama-8B, and Mistral-8B. An overview of mean FPR across open-source models is reported in

Table 1. For complete evaluation results, including excluded models, see

Appendix A.

We observe substantial variation in ethical detection performance across model families and scales. While our evaluation does not assume access to proprietary training details, we hypothesize that these differences are influenced by the composition of pretraining data and the objectives of instruction tuning. Models such as Qwen emphasize general instruction following and multilingual natural language understanding, which may enhance sensitivity to linguistic semantics even when embedded in code. In contrast, code-specialized models are primarily optimized for functional correctness and code generation, potentially deprioritizing non-executable natural language content such as comments or identifiers. These architectural and training differences provide a plausible explanation for why mid-scale instruction-tuned models occasionally outperform larger or more code-focused counterparts in ethical sensitivity.

5.1. RQ1: Accuracy of Detecting Ethically Problematic Language

5.1.1. Overall Detection Trends

As presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3, the

Llama-70B model achieves strong sentence-level detection performance, exceeding a detection rate of 0.85 on both Python and C corpora. However, detection performance declines markedly at the token level across all models. Notably,

Qwen-14B outperforms the larger

Llama-70B in several token-level scenarios. These results suggest that robustness is not solely determined by model family or parameter scale, but is also influenced by training data quality, instruction alignment, and architectural design.

5.1.2. Surface-Wise Vulnerabilities

Across all models, higher detection rates are consistently observed for adversarial perturbations applied to print statements and variable names. In contrast, inline comments remain the most difficult surface to detect. This highlights a critical vulnerability: although comments are non-executable, they can inconspicuously carry harmful or biased language, making them a particularly sensitive attack surface in real-world programming environments.

5.1.3. Closed-Source Models

As shown in

Table 4, closed-source GPT models (e.g.,

GPT-4.1,

GPT-4o) exhibit consistent scaling behavior under both sentence-level and token-level perturbations. These models outperform open-source counterparts, particularly in detecting adversarial content embedded within inline

comments, which remain challenging for most models. Nevertheless, even the strongest GPT models show persistent weaknesses on problematic expressions embedded in

function names. This indicates that while instruction tuning and proprietary data contribute to improved robustness, blind spots remain at the intersection of code structure and semantics.

5.2. RQ2: Robustness Variation Across Model Families, Scales, and Prompt Framing

5.2.1. Model Family Analysis

Qwen Family

The Qwen models demonstrate strong instruction-following capabilities that contribute to robustness in adversarial detection. Even the 3B variant maintains a false positive rate (FPR) below 30%, outperforming Llama-8B in both precision and recall. Within the family, the Qwen-14B model achieves the best overall performance, surpassing the 32B model in detection accuracy. Although it shows some degradation at the token level, the decline is relatively small, enabling Qwen-14B to match or even exceed the token-level performance of the larger Llama-70B model.

Llama Family

Due to high FPR in smaller variants, only the Llama-70B model was considered for detailed evaluation. Despite its scale, Llama-70B exhibits a higher FPR than Qwen-7B. Nevertheless, its sentence-level detection performance remains competitive, ranking among the strongest open-source models. It also performs reasonably well on comment-level perturbations. However, its weaker performance on function-name injections, combined with substantial computational cost, raises concerns about efficiency and practicality.

Code Llama Family

To compare code-specialized models, we additionally evaluated the Code Llama family on Python. The 7B variant was excluded due to an excessively high FPR (0.83). The 13B model, while comparable in scale to Qwen-14B, demonstrated substantially lower detection performance. This indicates that code specialization in Code Llama does not necessarily translate into improved robustness against adversarial inputs. On the contrary, these results suggest that code-specialized models may remain vulnerable to ethically problematic language embedded in source code, despite optimization for programming tasks.

Mistral Family

The Mistral-8B model was excluded due to excessively high FPR, while the larger Mistral-Small demonstrates among the lowest detection rates across evaluated models. Under the code condition, its performance declines sharply, suggesting limited robustness to code-aware adversarial inputs. By contrast, detection improves under the natural-language condition, indicating that Mistral models may struggle more with structured code contexts than with general textual content.

GPT Family

GPT models generally show improved detection performance as scale and capability increase. Although the exact parameter sizes of GPT-4o and GPT-4.1 are undisclosed, GPT-4.1—reported to be specialized for code understanding—consistently outperforms GPT-4o in detecting ethically problematic language within source code. This suggests that instruction tuning optimized for programming tasks enhances robustness against adversarial linguistic inputs in structured environments.

Nevertheless, GPT-4.1 achieves higher performance under the natural-language condition than under the code condition, indicating that even code-specialized models struggle to identify adversarial content when it is syntactically embedded within source code. This limitation underscores the need for finer-grained sensitivity to linguistic perturbations in structured programming contexts.

5.2.2. Model Scale

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between model scale and average ethical detection performance. Contrary to a simple scaling hypothesis, larger models do not consistently outperform smaller or mid-scale models. For example, Qwen-14B achieves higher mean scores than Qwen-32B, indicating that increased parameter count alone does not guarantee improved ethical sensitivity. To improve interpretability, numerical values are explicitly annotated in the figure, enabling direct comparison across model sizes. These results suggest that architectural design choices and training objectives play a more critical role than scale alone.

In contrast, the

GPT-4o and

GPT-4.1 series (

Table 4) demonstrate a clear scaling trend, with performance consistently improving as model size increases. This distinction suggests that while open-source models may suffer from architectural or training inconsistencies across scales, closed-source models—likely benefiting from proprietary training methods and data—tend to scale more predictably in terms of adversarial robustness.

5.2.3. Prompt Framing

Prompt formulation has a significant impact on detection performance. As reported in

Table 2 and

Table 3, models generally achieve higher accuracy in detecting ethically problematic

comments under the

natural-language condition. For example, Qwen-32B’s Python comment detection improves from 0.28 to 0.60, while Mistral-Small’s C comment detection increases by more than 25 points.

In contrast, detection performance on print statements declines for most models. For instance, Llama-70B drops from 0.98 to 0.95 when evaluated under the natural-language condition. This pattern suggests that the code condition directs model attention toward executable syntax, thereby reducing sensitivity to natural-language semantics in non-functional regions.

Interestingly, both the code-specialized

Code Llama-13B and the

GPT-4.1 series achieve higher detection rates under the

natural-language condition compared to the

code condition (

Table 4 and

Table 5). This pattern indicates that even code-specialized models may overlook embedded toxicity when inputs are explicitly framed as source code, suggesting a persistent limitation in their ability to attend to ethically problematic language within structurally presented code.

These findings emphasize the importance of evaluating ethical robustness under diverse prompt formulations, as framing alone can substantially alter which vulnerabilities are exposed.

5.3. RQ3: Failure Modes Across Perturbation Types and Code Surfaces

5.3.1. Surface-Specific Weaknesses

Detection performance varies substantially by input surface. Across models,

print statements and variable names are detected most reliably, likely due to their prevalence and semantic clarity. In contrast, inline

comments consistently yield the lowest detection rates (

Table 2 and

Table 3), exposing a critical vulnerability. Although non-executable, comments can inconspicuously carry offensive or biased language, and most models fail to robustly attend to them.

A qualitative inspection of representative failure cases suggests several plausible explanations for this behavior. First, inline comments are often treated as auxiliary or non-essential context during code understanding, leading models to implicitly deprioritize them relative to executable tokens. Second, comments are frequently interleaved with syntactic elements, which may cause their semantic content to be diluted or overshadowed by surrounding code structure. Finally, unlike print statements or identifiers, comments do not directly contribute to program outputs or variable usage, potentially reducing the attention allocated to them in zero-shot settings. These observations indicate that current LLMs may implicitly optimize for functional reasoning at the expense of ethical scrutiny over non-executable language.

5.3.2. Cross-Language Generalization

Detection performance on C code is consistently weaker than on Python, regardless of prompt framing (

Table 2 and

Table 3). This indicates that models are more strongly aligned to Python-like syntax and semantics, reflecting a training bias. Notably, C

function names often perform worse than comments, unlike their Python counterparts. This may be attributed to unfamiliar declaration patterns (e.g.,

int func() vs.

def func():). These findings suggest a broader generalization gap in current code-aligned LLMs across programming languages and input-surface types.

6. Conclusions

We introduced Code Redteaming, a framework for evaluating the ethical robustness of code-oriented language models by injecting adversarial natural language into non-functional components of source code. Unlike prior work focusing on output-level safety, our approach exposes input-side vulnerabilities that are often overlooked in code-based applications. Experimental results across multiple model families and programming languages show that ethical sensitivity does not consistently improve with scale and that token-level perturbations in user-facing elements remain a significant challenge. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating ethical robustness in code inputs, particularly in educational and collaborative programming settings.

Limitations and Future Work

This study focuses on ethically problematic natural language embedded in non-functional components of Python and C code under a binary detection setting. In particular, the false positive rate (FPR) threshold used to filter unreliable models should be interpreted as a research-oriented reliability criterion rather than a deployable standard. In practical software engineering settings such as IDE linters or CI/CD pipelines, even substantially lower FPRs would be required for user adoption. Future work will extend Code Redteaming to additional programming languages and multilingual codebases, as well as explore more fine-grained ethical categories beyond binary classification. Another promising direction is the integration of contextual execution traces and adaptive adversarial strategies, which may further expose latent vulnerabilities in code-oriented language models. We believe that such extensions will contribute to more comprehensive and realistic evaluations of ethical robustness in real-world programming environments.

Additionally, our evaluation enforces a strict binary classification format, requiring models to output either 0 or 1. Modern instruction-tuned LLMs, particularly those aligned via reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), may prioritize refusal behaviors when encountering harmful content rather than explicit classification. Such refusal responses were treated as malformed outputs and excluded from scoring, which may underrepresent certain safety-aligned behaviors. Future work should explore evaluation protocols that explicitly account for refusal as a valid safety signal, bridging the gap between detection-oriented and moderation-oriented model behaviors.

Finally, the adversarial natural language used in this benchmark was generated using GPT-4o, which is also among the top-performing models evaluated in our experiments. This introduces a potential distributional bias, whereby models from the same family may be better at detecting content generated by similar training distributions. While we observe consistent trends across both open-source and proprietary models, future benchmarks should incorporate content generated by diverse sources to mitigate such circular dependencies.