Analysis of Discretization Errors in the Signal Model of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The output signal model of the integrate-and-dump filter is derived using the discrete-time accumulation computation method. To investigate navigation spoofing techniques, a more precise integrate-and-dump filter output signal model was provided.

- From a qualitative perspective, it is demonstrated that the discretization error in the traditional integrate-and-dump filter output signal model derived via the continuous-time integration approach is negligible only under the ideal condition where the receiver tracks the input satellite signal without any error. In practical scenarios, however, the discretization error inevitably exists.

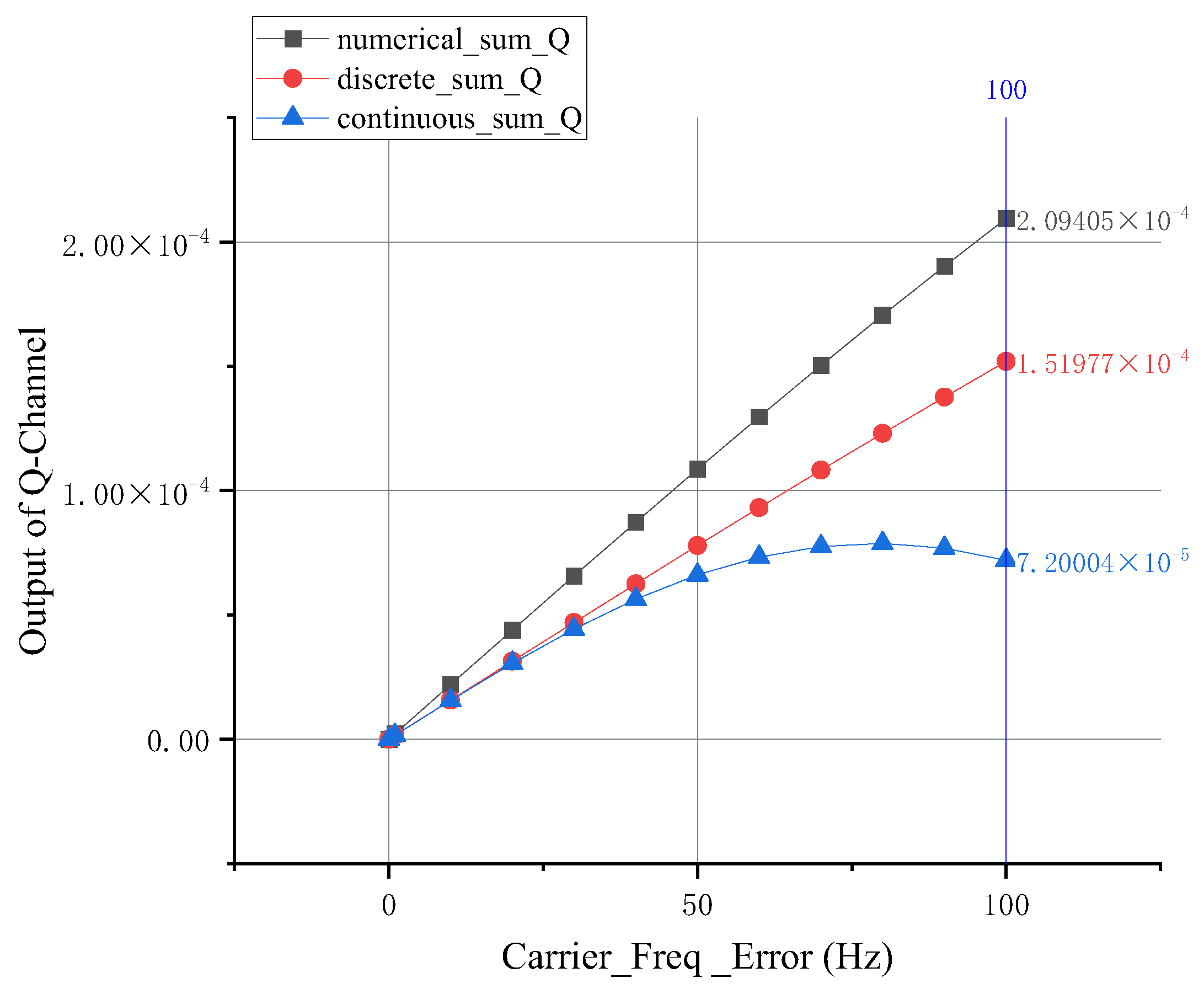

- Quantitative simulations reveal that when only ranging code phase error and initial carrier phase error are present, the results from the traditional integrate-and-dump filter output signal model, derived from continuous-time integration, align closely with the computational outcomes of the discrete-time accumulation-based model proposed in this paper, as well as with reference values obtained through numerical calculations. This consistency suggests that under these conditions, the discretization error is negligible. However, when carrier frequency error is introduced, the accuracy of the proposed model significantly exceeds that of the traditional model, indicating that the discretization error becomes pronounced and increases markedly with the magnitude of the frequency error.

2. Input Signal Model and Tracking Loop of Satellite Navigation Receivers

2.1. Input Signal Model of Satellite Navigation Receivers

2.2. The Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers

3. Output Signal Modeling of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Continuous-Time Integration

3.1. Modeling the Output Signal of the In-Phase Channel Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Continuous-Time Integration

3.2. Modeling the Output Signal of the Quadrature-Phase Channel Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Continuous-Time Integration

4. Output Signal Modeling of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Discrete-Time Summation

4.1. Discretization of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter Output Signal Model and Definition of Discretization Error

4.2. Modeling the Output Signal of the In-Phase Channel Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Discrete-Time Summation

4.3. Modeling the Output Signal of the Quadrature-Phase Channel Integrate-And-Dump Filter via Discrete-Time Summation

4.4. Qualitative Analysis of Discretization Error in Integrate-And-Dump Filters Under Steady-State Conditions

5. Experiments

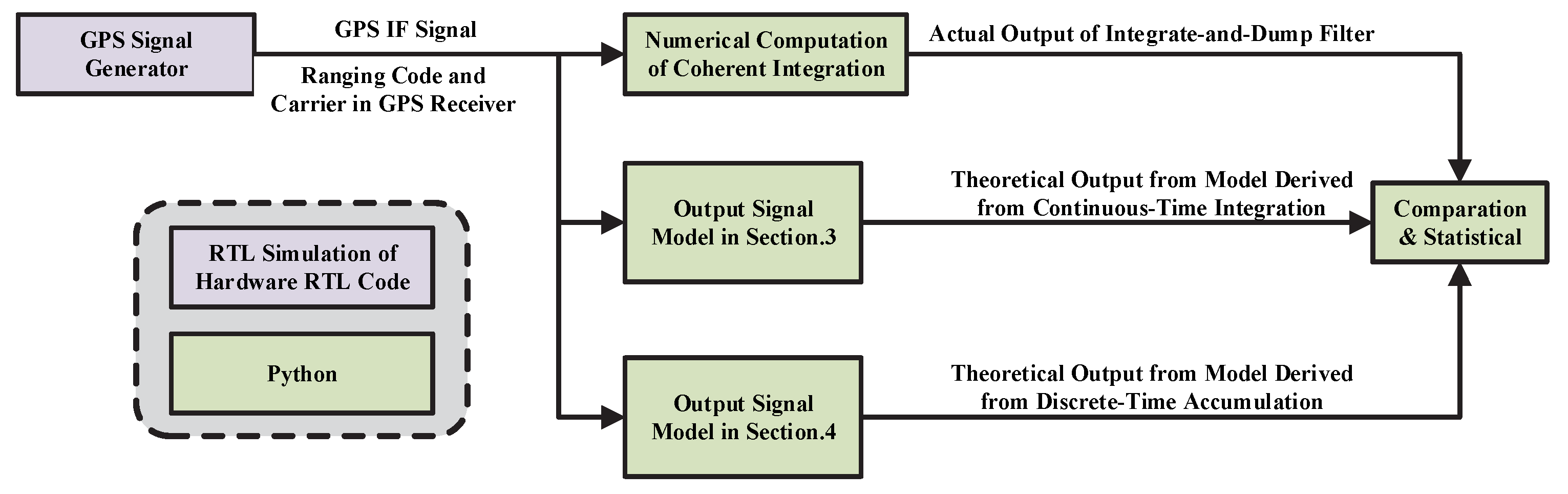

5.1. Experimental Objectives and Design

5.2. Experimental Environment and Setup

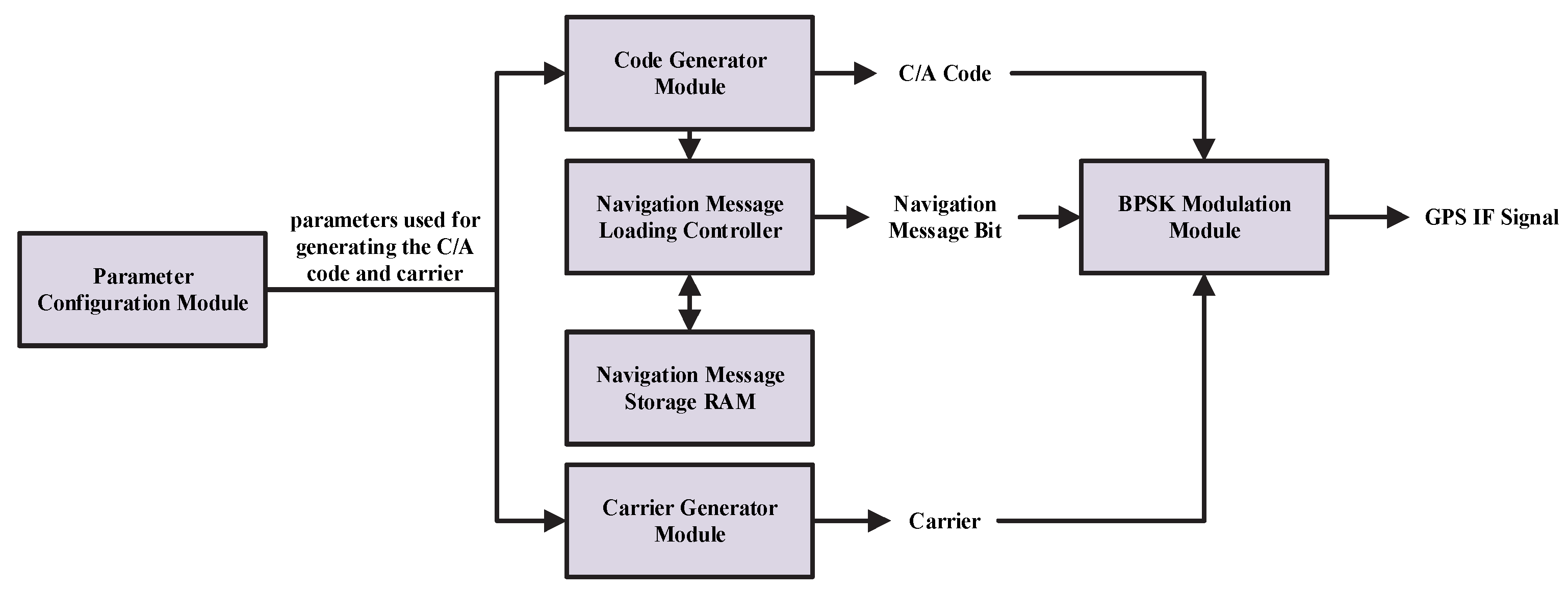

5.3. Intermediate Frequency Signal Generation Based on a GPS Satellite Signal Generator

5.4. Validation Results of the Derived Integrate-And-Dump Filter Output Signal Model

- (1)

- Parameter Settings of the Integrator-and-Dump Filter

- (2)

- Verification Method

- (3)

- Experimental Results Under Different Ranging Code Phase Error Conditions

- (4)

- Experimental Results Under Different Initial Carrier Phase Error Conditions

- (5)

- Experimental Results Under Different Carrier Frequencies

5.5. Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L. A survey of GNSS spoofing and anti-spoofing technology. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Radke, K.; Camtepe, S.; Foo, E.; Ren, M. A survey and analysis of the GNSS spoofing threat and countermeasures. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2016, 48, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.G.; Closas, P.; Broumandan, A.; Volakis, J.L. Vulnerabilities, threats, and authentication in satellite-based navigation systems. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psiaki, M.L.; Humphreys, T.E. GNSS spoofing and detection. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Fu, Q.; Liu, B. Research progress of GNSS spoofing and spoofing detection technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Xi’an, China, 16–19 October 2019; pp. 1360–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Broumandan, A.; Siddakatte, R.; Lachapelle, G. An approach to detect GNSS spoofing. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2017, 32, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani-Darian, P.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Closas, P. Detecting GNSS spoofing using deep learning. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2024, 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmaier, F.; Chen, Y.; Lo, S.; Walter, T. GNSS spoofing detection through spatial processing. Navigation 2021, 68, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoš, K.; Brkić, M.; Begušić, D. Recent advances on jamming and spoofing detection in GNSS. Sensors 2024, 24, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q. Analysis of Kalman filter innovation-based GNSS spoofing detection method for INS/GNSS integrated navigation system. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 5167–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Bian, S.; Cao, K.; Ji, B. GNSS spoofing detection based on new signal quality assessment model. GPS Solut. 2018, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-K.; Miralles, D.; Akos, D.; Konovaltsev, A.; Kurz, L.; Lo, S.; Nedelkov, F. Detection of GNSS spoofing using NMEA messages. In Proceedings of the 2020 European Navigation Conference (ENC), Dresden, Germany, 23–24 November 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Borhani-Darian, P.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Closas, P. Deep neural network approach to detect GNSS spoofing attacks. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2020), Online, 22–25 September 2020; pp. 3241–3252. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, C.; Liu, R. Spoofing and anti-spoofing technologies of global navigation satellite system: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165444–165496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Sun, F.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Cui, J. GNSS spoofing mitigation with a multicorrelator estimator in the tightly coupled INS/GNSS integration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Tian, M.; Ji, Y.; Cheng, J.; Xie, Z.; Shao, S. Research on GNSS spoofing mitigation technology based on spoofing correlation peak cancellation. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 26, 3024–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oligeri, G.; Sciancalepore, S.; Di Pietro, R. GNSS spoofing detection via opportunistic IRIDIUM signals. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, Linz, Austria, 8–10 July 2020; pp. 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M.; Chowdhury, M. A sensor fusion-based GNSS spoofing attack detection framework for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 23559–23572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, D.; Xiao, K.; Dou, S.; Lu, X.; Sun, J. GNSS spoofing detection based on multicorrelator distortion monitoring. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, L. Asynchronous lift-off spoofing on satellite navigation receivers in the signal tracking stage. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 8604–8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, J.W. Engineering Satellite-Based Navigation and Timing: Global Navigation Satellite Systems, Signals, and Receivers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen, P.J.G.; Montenbruck, O. (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, G.; Schmidt, T.; Trainotti, C.; Mata-Calvo, R.; Fuchs, C.; Hoque, M.; Berdermann, J.; Furthner, J.; Günther, C.; Schuldt, T.; et al. Advanced technologies for satellite navigation and geodesy. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 64, 1256–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.W. Status, perspectives and trends of satellite navigation. Satell. Navig. 2020, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madry, S. Global Navigation Satellite Systems and Their Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, R.T.; Pany, T.; Gibbons, G. Known vulnerabilities of global navigation satellite systems, status, and potential mitigation techniques. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1174–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Space Force. Interface Control Documents (ICDs) & Interface Specifications (ISs). GPS.gov. Available online: https://www.gps.gov/interface-control-documents-icds-interface-specifications-iss (accessed on 26 November 2025).

| Parameters Used for Generating the C/A Code | Parameters Used for Generating Carrier | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SV ID | No. 1 | frequency of carrier | 5.0 Mhz |

| initial code count | 0 chip | initial phase of carrier | 0 rad |

| initial phase of the initial code chip | 0 chip | amplitude of carrier | 1.0 V |

| CA_Code_Error/Chip | Numerical_Sum_I | Discrete_Sum_I | Continuous_Sum_I |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.999999997158 × 10−4 | 5.000000000000 × 10−4 | 5.000000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.125 | 4.376312525976 × 10−4 | 4.375000000000 × 10−4 | 4.375000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.25 | 3.751753314078 × 10−4 | 3.750000000000 × 10−4 | 3.750000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.375 | 3.127238640510 × 10−4 | 3.125000000000 × 10−4 | 3.125000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.5 | 2.500419028446 × 10−4 | 2.500000000000 × 10−4 | 2.500000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.625 | 1.871505947997 × 10−4 | 1.875000000000 × 10−4 | 1.875000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.75 | 1.244553337907 × 10−4 | 1.250000000000 × 10−4 | 1.250000000000 × 10−4 |

| 0.875 | 6.206546844291 × 10−5 | 6.250000000000 × 10−5 | 6.250000000000 × 10−5 |

| 1 | −5.136220313802 × 10−8 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| CA_Code_Error/Chip | Numerical_Sum_Q | Discrete_Sum_Q | Continuous_Sum_Q |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1.163311852706 × 10−16 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.125 | 2.292335467488 × 10−8 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.25 | 9.480574595260 × 10−8 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.375 | −1.517970746122 × 10−7 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.5 | −3.117096183879 × 10−7 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.625 | −3.030659114376 × 10−7 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.75 | −1.378690759851 × 10−8 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 0.875 | 1.432603077285 × 10−7 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| 1 | −1.163311852706 × 10−16 | 0.000000000000 | 0.000000000000 |

| Carrier _Initial_Phase_Error/° | Numerical_Sum_I | Discrete_Sum_I | Continuous_Sum_I |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 |

| 60 | 2.50000000 × 10−4 | 2.50000000 × 10−4 | 2.50000000 × 10−4 |

| 120 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 |

| 180 | −5.00000000 × 10−4 | −5.00000000 × 10−4 | −5.00000000 × 10−4 |

| 240 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 | −2.50000000 × 10−4 |

| 360 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 | 5.00000000 × 10−4 |

| Carrier_Initial_Phase_Error/° | Numerical_Sum_Q | Discrete_Sum_Q | Continuous_Sum_Q |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1.16331185 × 10−16 | 0.00000000 | 0.00000000 |

| 60 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 |

| 120 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 | 4.33012702 × 10−4 |

| 180 | 5.58719301 × 10−16 | 6.12323400 × 10−20 | 6.12323400 × 10−20 |

| 240 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 |

| 300 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 | −4.33012702 × 10−4 |

| 360 | 2.34492444 × 10−16 | −1.22464680 × 10−19 | −1.22464680 × 10−19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tie, J.; Xun, C.; Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L. Analysis of Discretization Errors in the Signal Model of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers. Mathematics 2026, 14, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010188

Tie J, Xun C, Guo Y, Luo L, Lu M, Wang Y, Zhou L. Analysis of Discretization Errors in the Signal Model of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleTie, Junbo, Changqing Xun, Yan Guo, Li Luo, Menglong Lu, Yongwen Wang, and Li Zhou. 2026. "Analysis of Discretization Errors in the Signal Model of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010188

APA StyleTie, J., Xun, C., Guo, Y., Luo, L., Lu, M., Wang, Y., & Zhou, L. (2026). Analysis of Discretization Errors in the Signal Model of the Integrate-And-Dump Filter in Satellite Navigation Receivers. Mathematics, 14(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010188