Optimization Techniques for Improving Economic Profitability Through Supply Chain Processes: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Which optimization techniques have been applied to improve economic profitability through supply chain processes?

- Which Value Drivers are being addressed through the application of optimization techniques?

- In which Supply Chain processes are the proposed optimization techniques being applied?

2. Background

2.1. Supply Chain

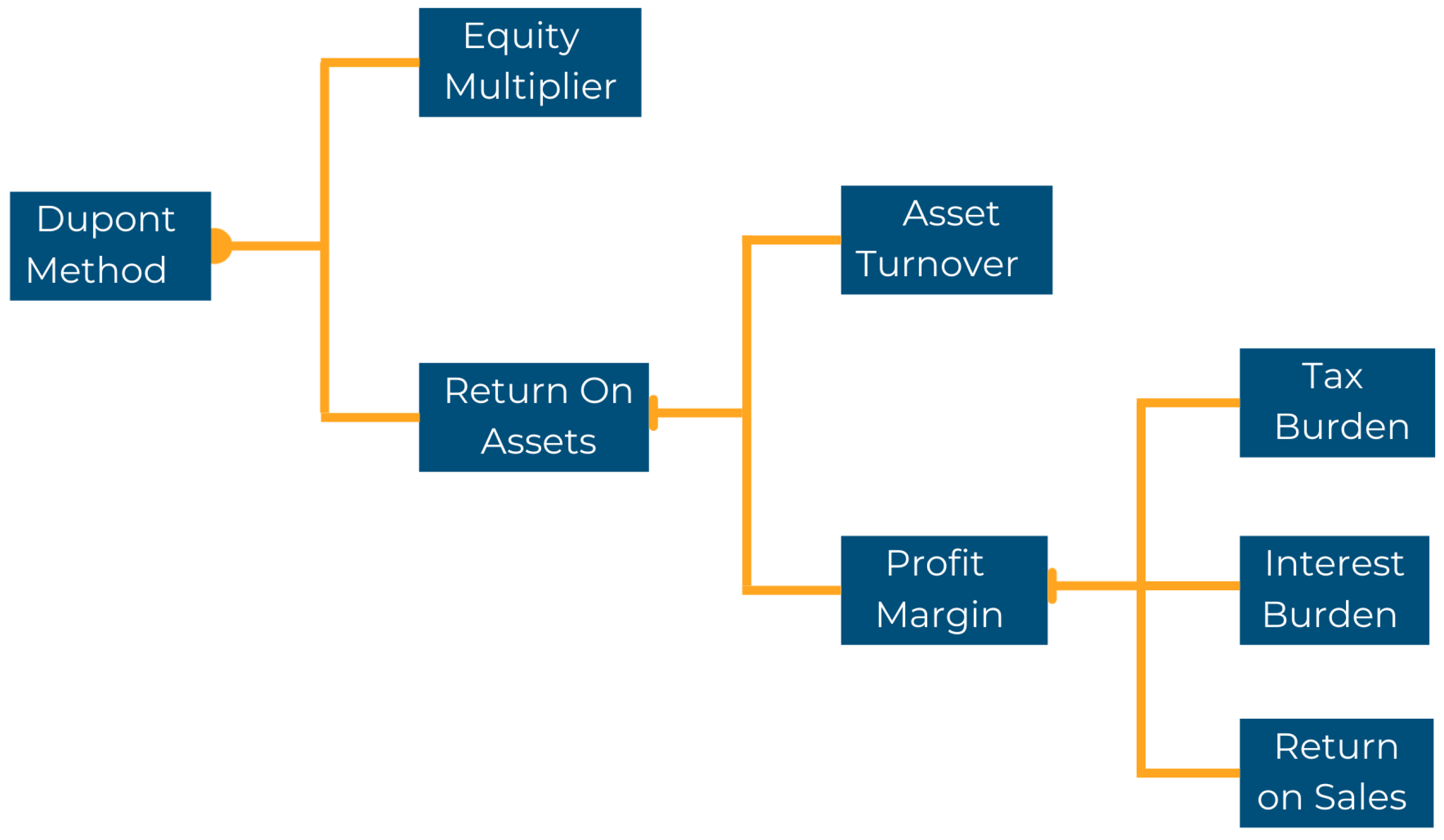

2.2. Economic Profitability

- Financial profitability: It is a measure, referred to a specific period of time, of the company’s own funds (equity).

- Economic profitability: It is a measure referred to a specific period of time, independent of its financing.

- Operating Income = Revenue − Cost of Good Sold − Operating Expenses − Depreciation − Amortization

- Tax Rate = The relevant income or profit tax rate in the country.

- E = Market value of the firm’s equity.

- D = Market value of the firm’s debt.

- V = E + D.

- Re = Cost of equity.

- Rd = Cost of debt.

- Tc = Corporate tax rate.

- TD & Leases = Total Debt + Leases.

- TE & EE = Total Equity & Equity Equivalents = Common stock + Retained Earnings.

- Non-Operating Cash & Investments = Cash from Financing + Cash from Investing.

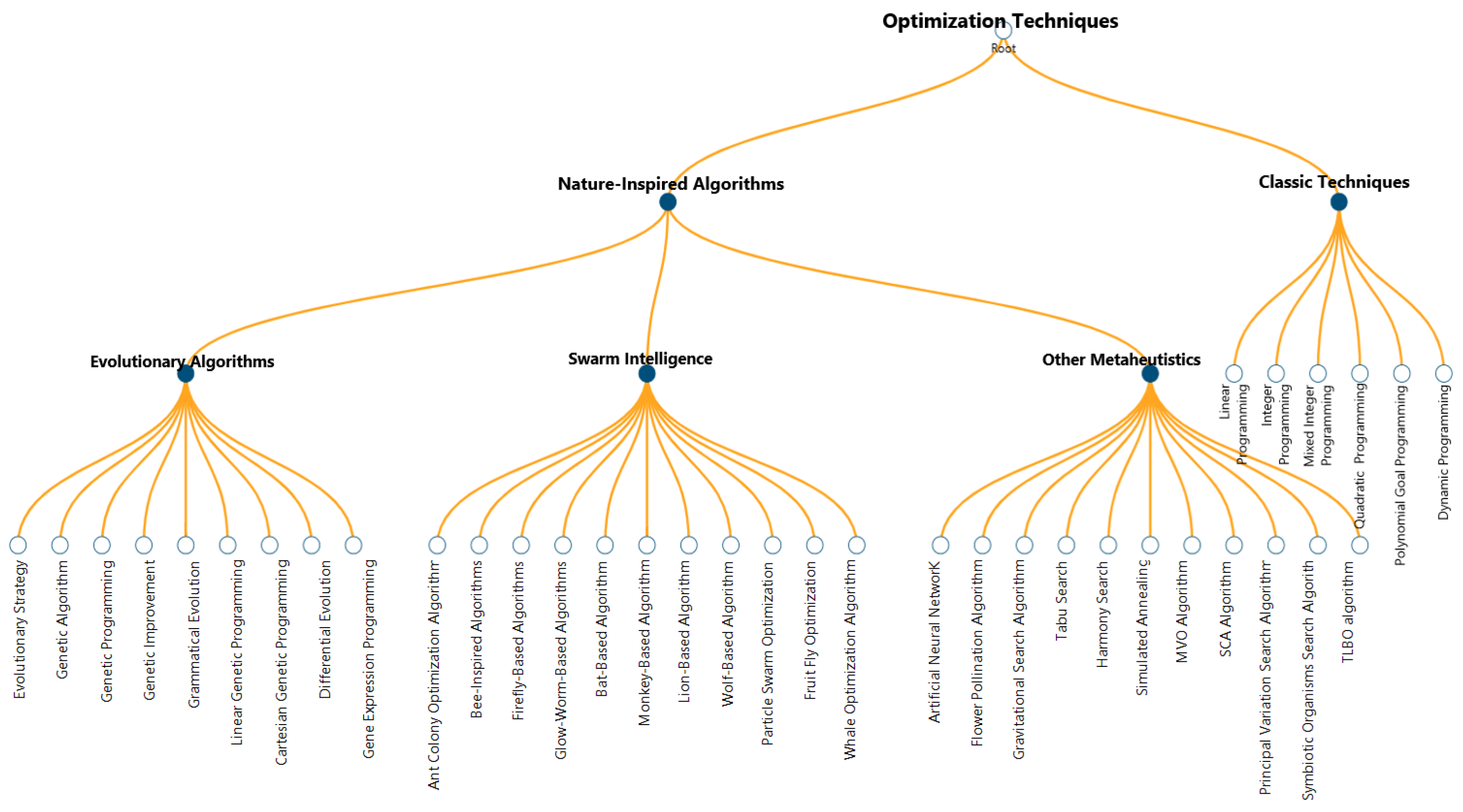

2.3. Optimization Techniques

- Conceptualization and problem definition;

- Mathematical formulation and representation;

- Solution and interpretation.

- Continuous Variables: This type of variable is suitable for representing quantities that can take any real value within a specific range, such as production quantities, inventory levels, or financial flows [45].

- Integer Variables: These variables are used in optimization problems where the decision variables must be whole numbers. This is common in scenarios such as programming, routing, and assignment, where fractional solutions are not feasible or do not make sense, such as the number of trucks or planes assigned to routes [46,47,48].

- Binary Variables: These variables naturally represent decisions that are binary in nature, such as whether an element should be included in a set or if a particular process should be activated. This simplifies the modeling of problems where decisions are inherently discrete, such as facility location, product assortment, and security games [49,50]. They allow for the representation of constraints and logical relationships within optimization models, which can be crucial for accurately capturing the problem structure [50].

- Stochastic Variables: In stochastic programming, decision variables can be classified as first-stage variables (here-and-now) or second-stage variables (wait-and-see), reflecting the timing of decisions in relation to the resolution of uncertainty [51].

- The weighted sum approach, which assigns a predefined weight to each objective [54].

- The epsilon-constraint method , which optimizes a main objective while restricting the values of the others [55].

- Goal programming, which seeks to minimize the deviation with respect to a predefined target value [45].

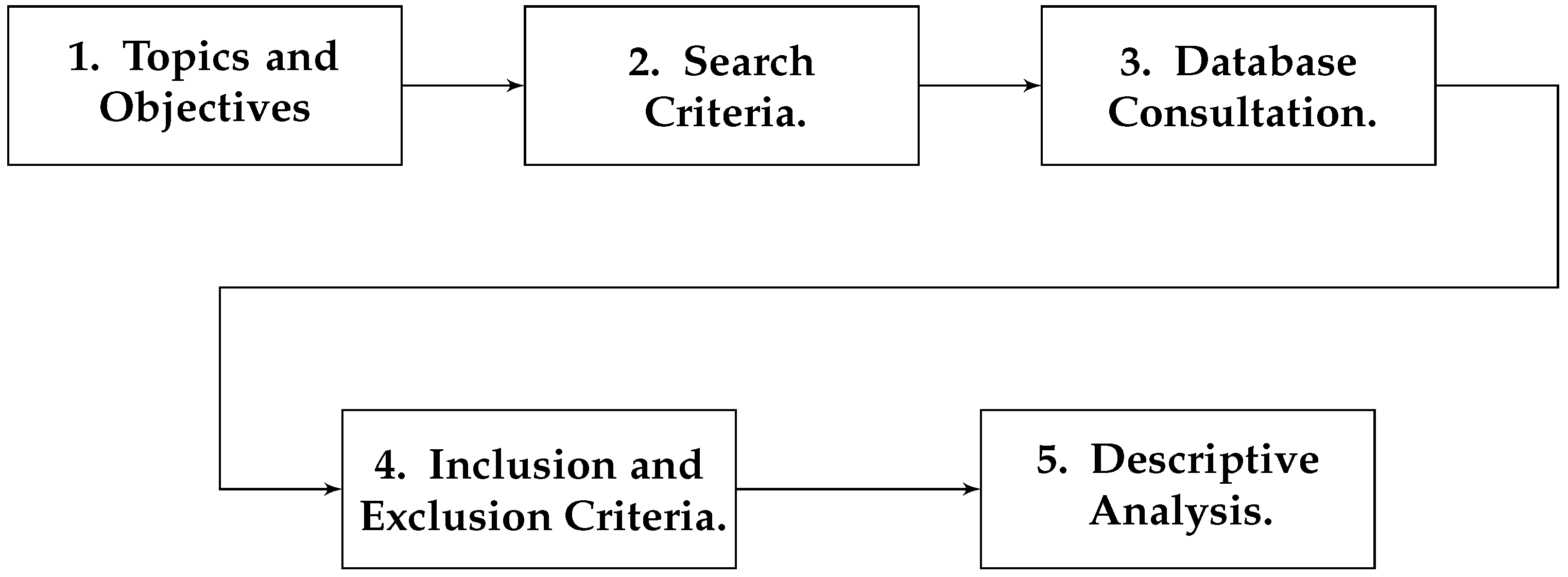

3. Methodology

3.1. Topics and Objectives

- To identify and classify the optimization techniques applied to supply chains to improve economic profitability.

- To determine the Value Drivers addressed through the application of the identified optimization techniques.

- To identify the Supply Chain processes in which the classified optimization techniques are applied.

3.2. Search Criteria

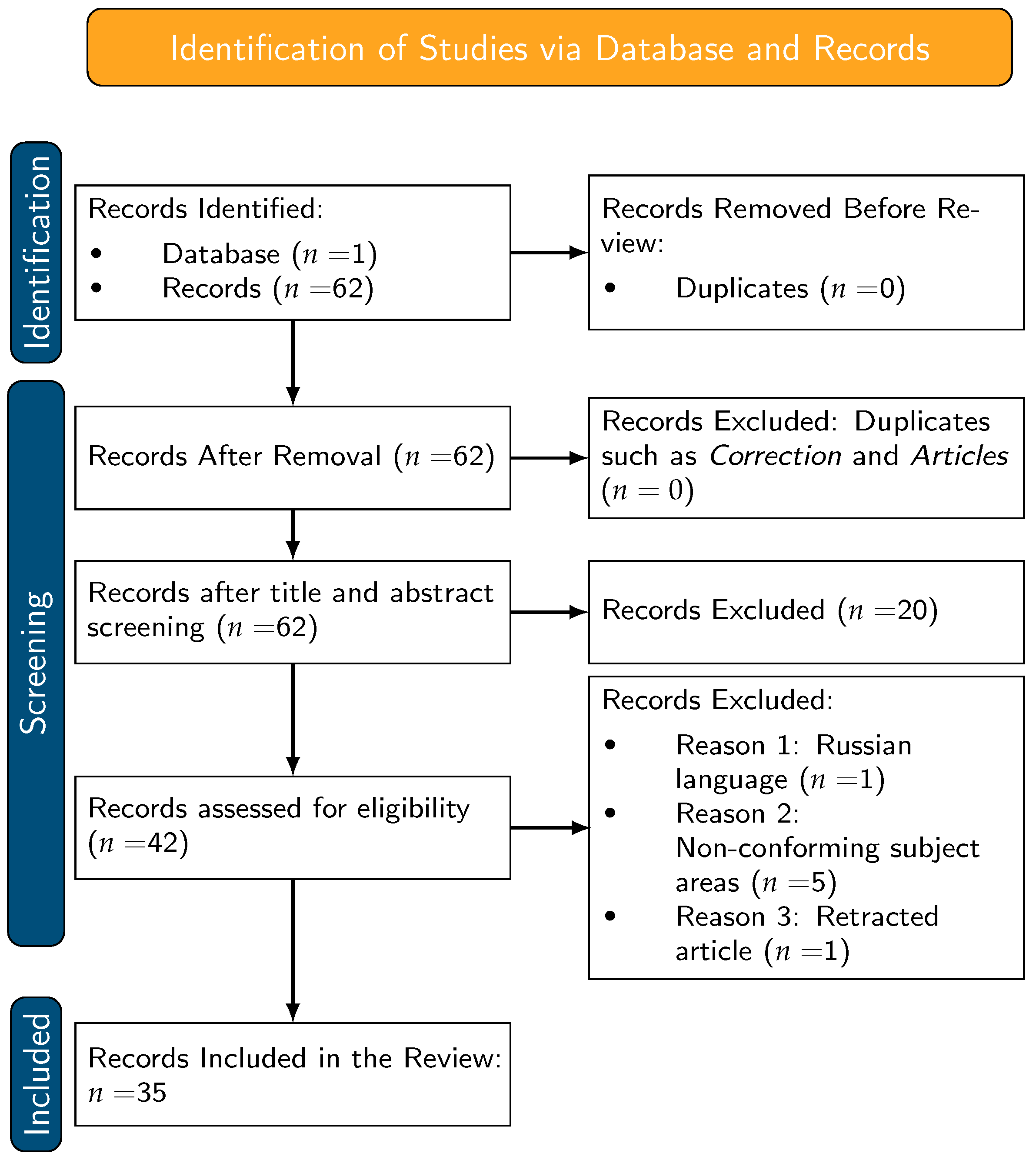

3.3. Database Consultation

- Key words: “supply chain*” OR “logistics” OR “supply network*” OR “value chain*” (Author Keywords) AND “supply chain*” OR “logistics” OR “supply network*” OR “value chain*” (Author Keywords) AND “financial impact” OR “financial performance” OR “economic performance” OR “cost reduction” OR “cost optimization” OR “revenue generation” OR “profitability” OR “working capital” OR “liquidity” OR “financial risk*” OR “cash flow” OR “return on investment” OR “ROI” (Author Keywords) AND “mathematical model*” OR “optimization” OR “optimisation” OR “algorithm*” OR “simulation” OR “predictive model*” OR “data analytic*” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “stochastic model*” OR “control theory” OR “game theory” OR “network model*” OR “forecasting model*” OR “statistical model*” OR “computational method*” OR “quantitative method*” (Author Keywords) and 2025 or 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 (Publication Years).

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

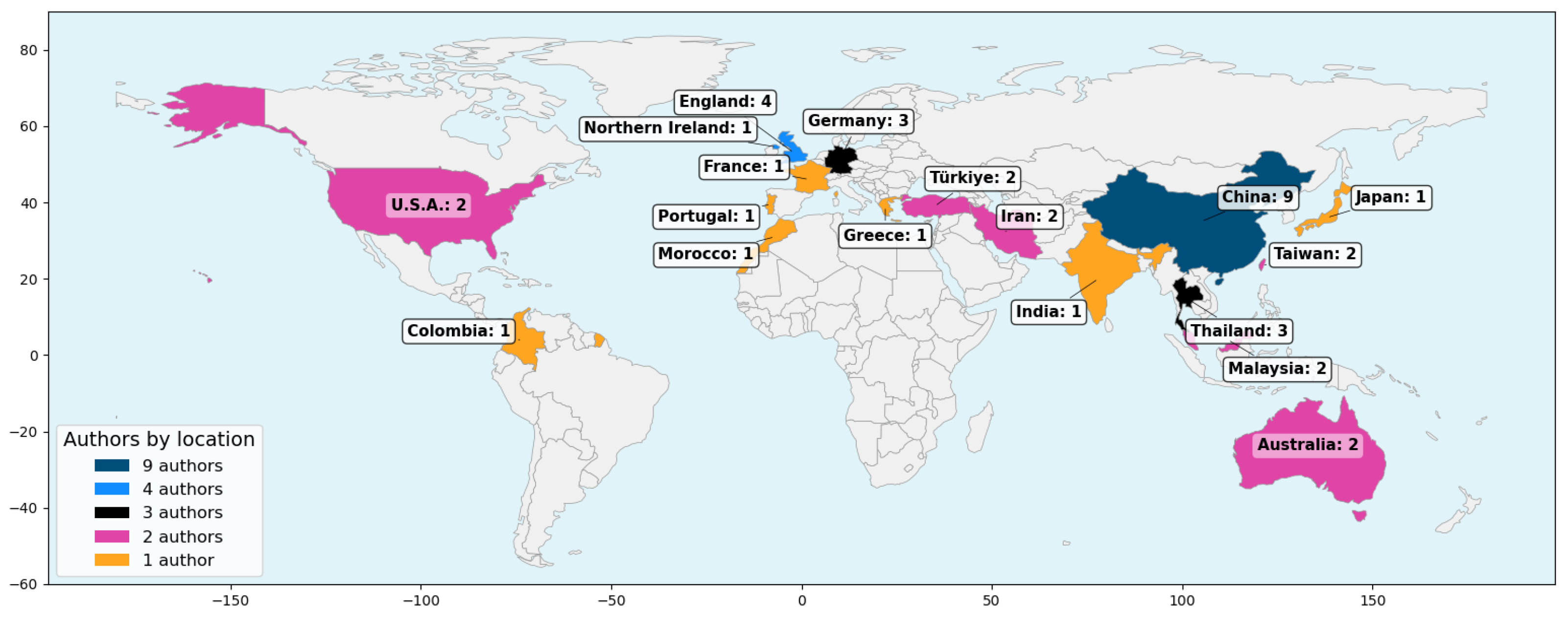

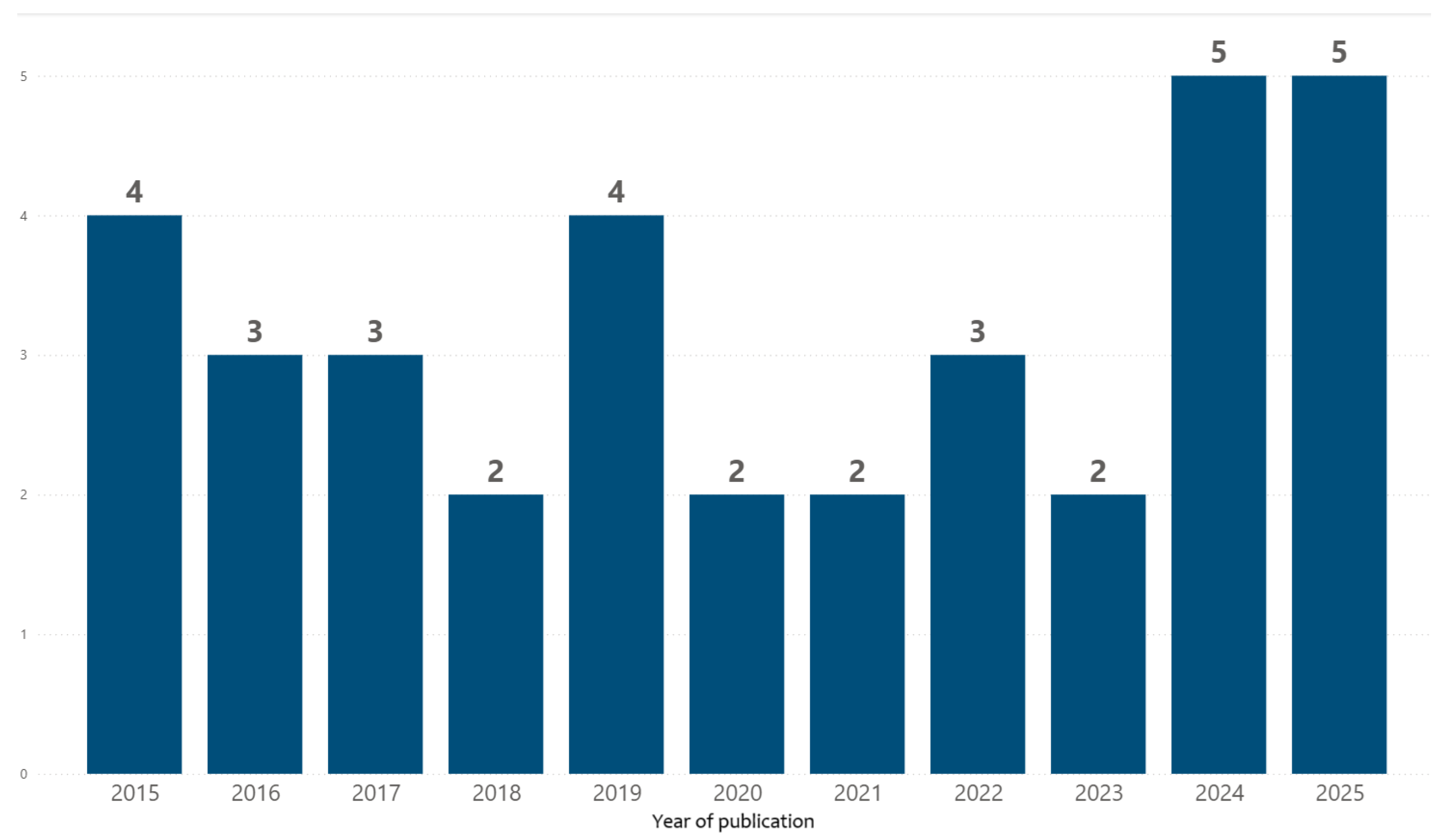

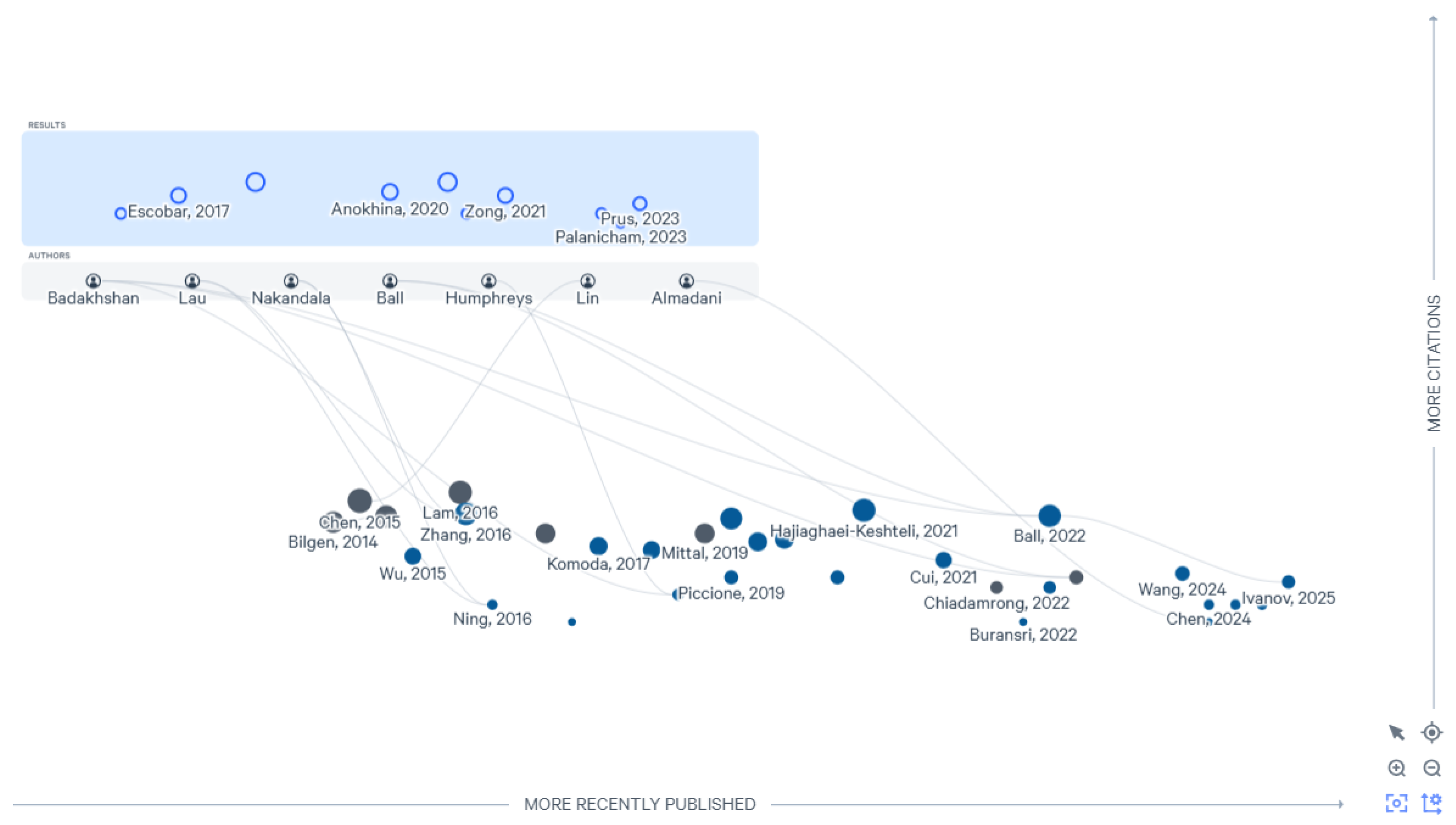

3.5. Descriptive Analysis

4. Findings

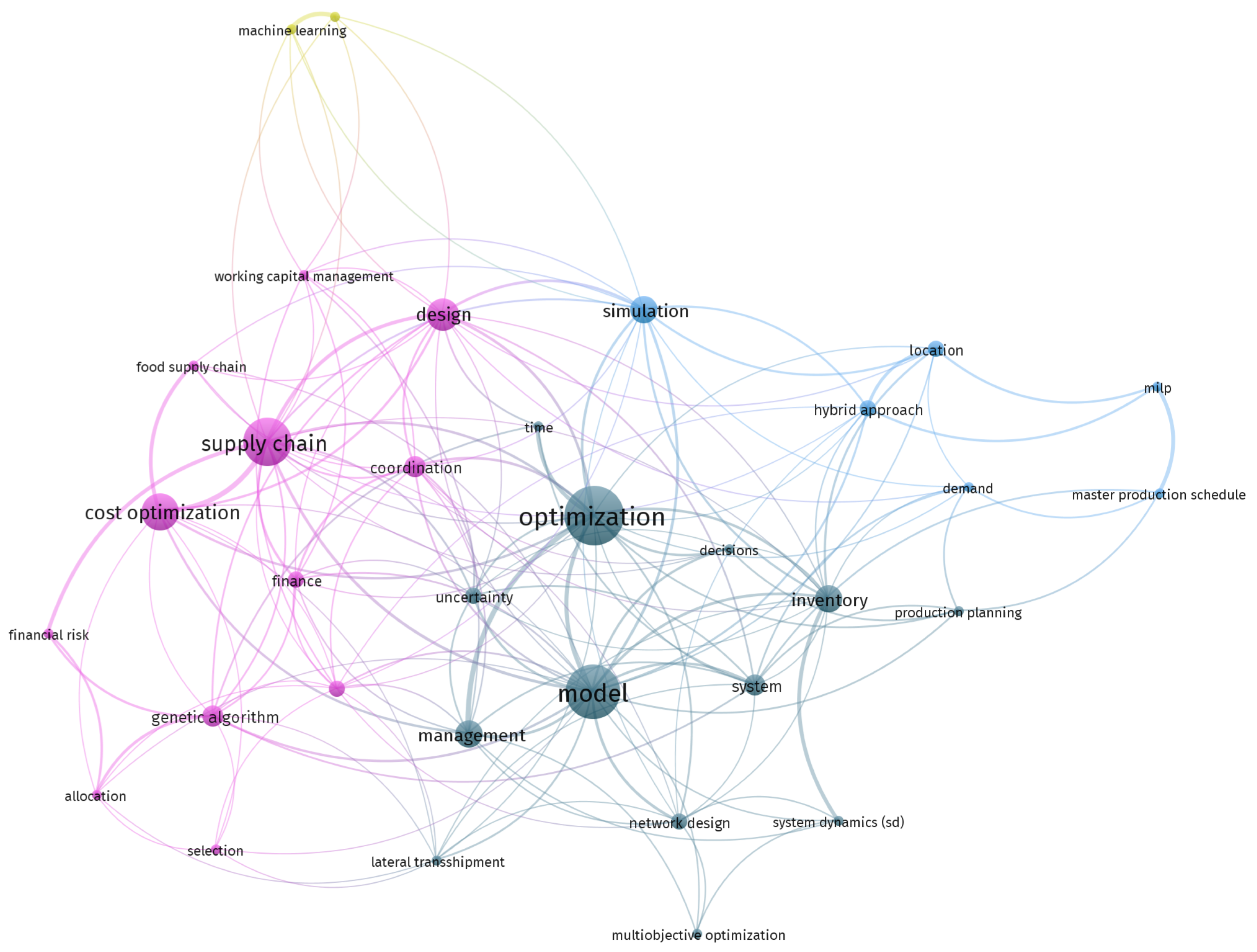

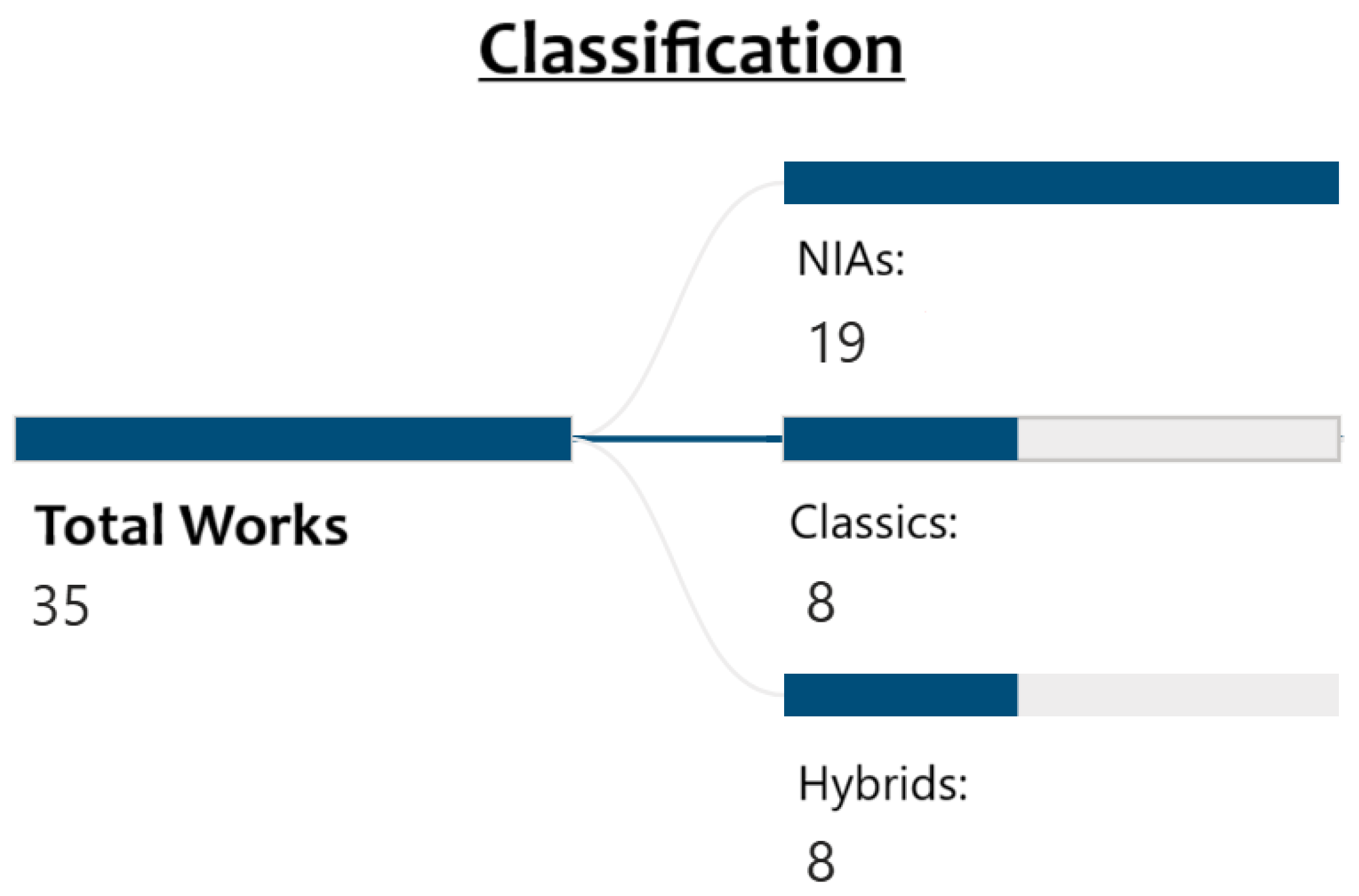

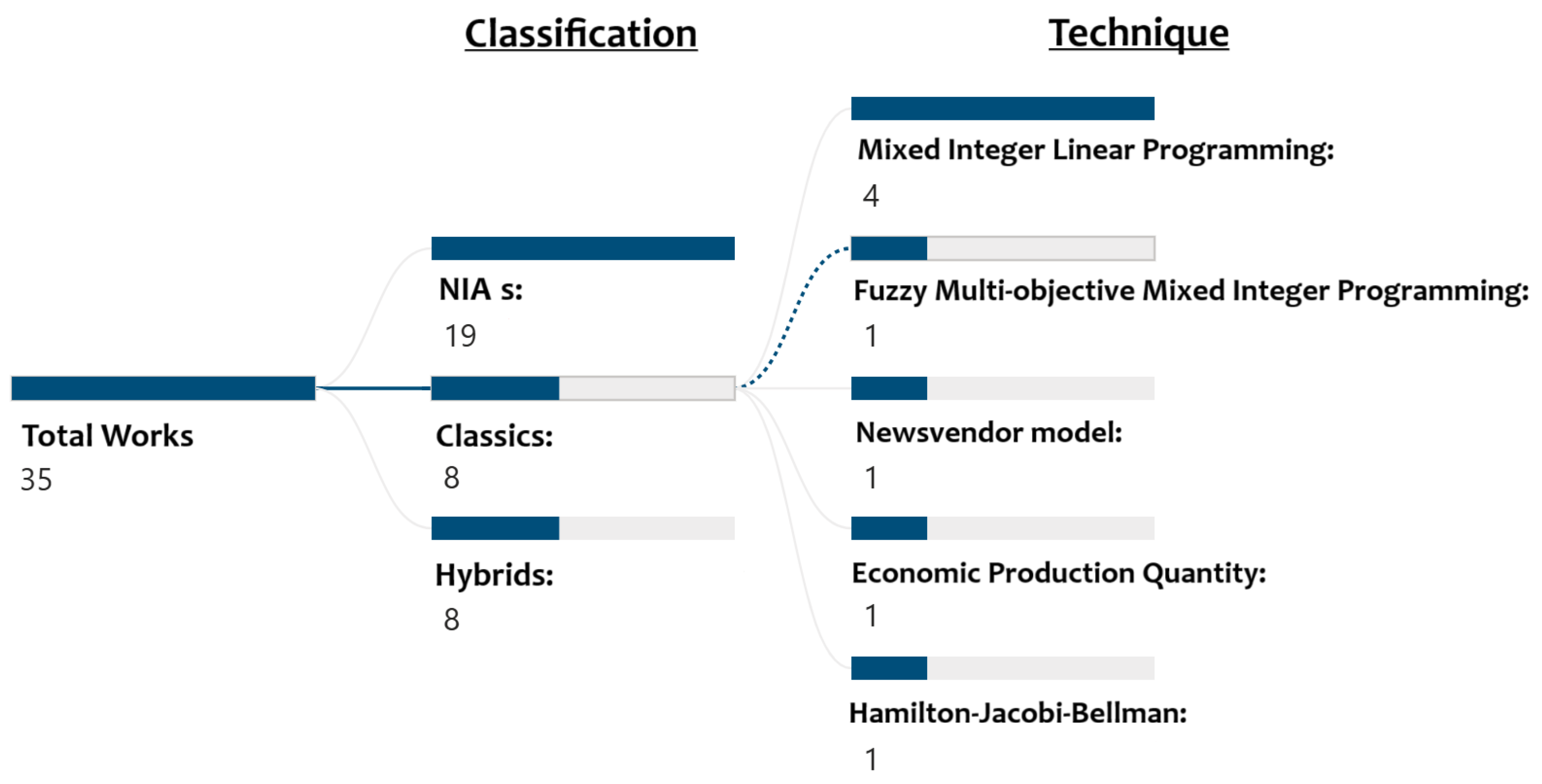

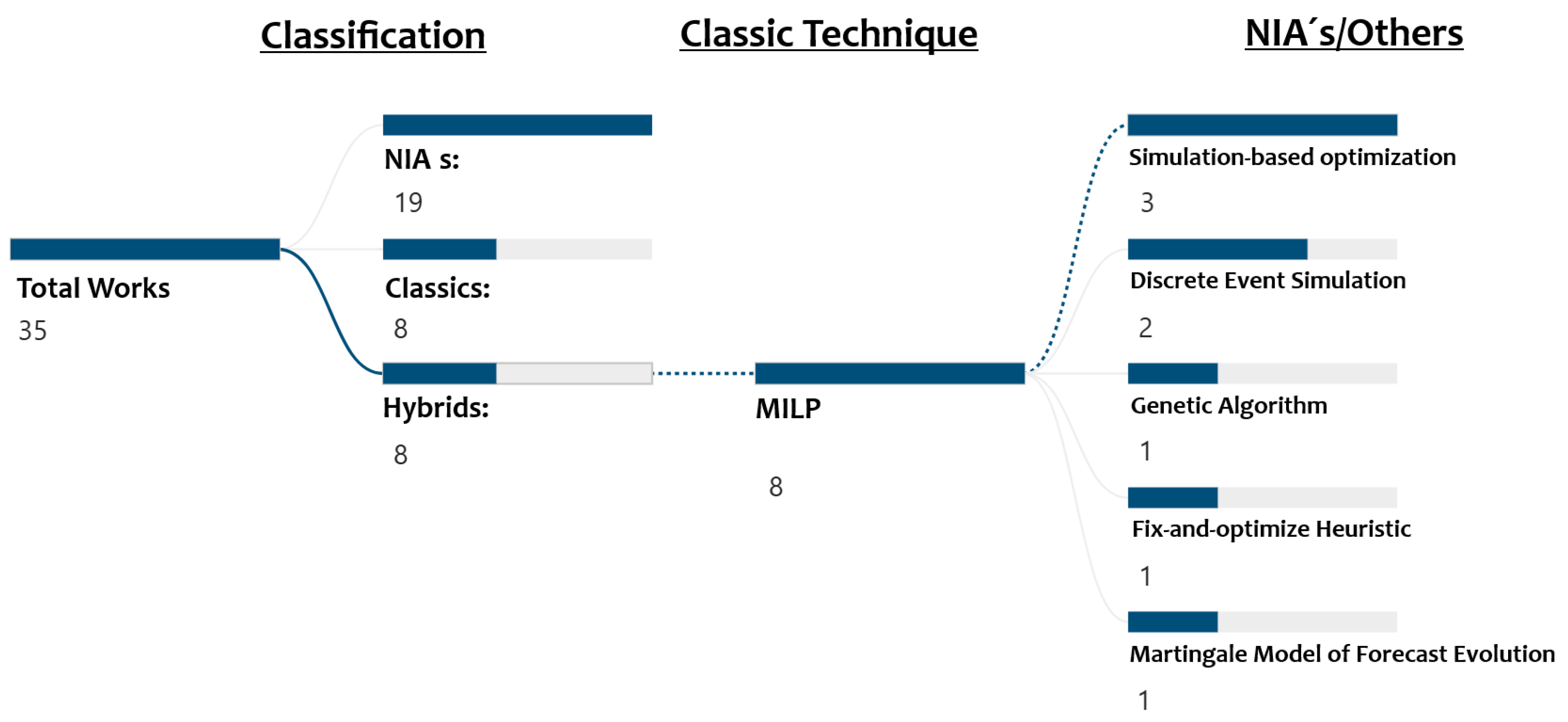

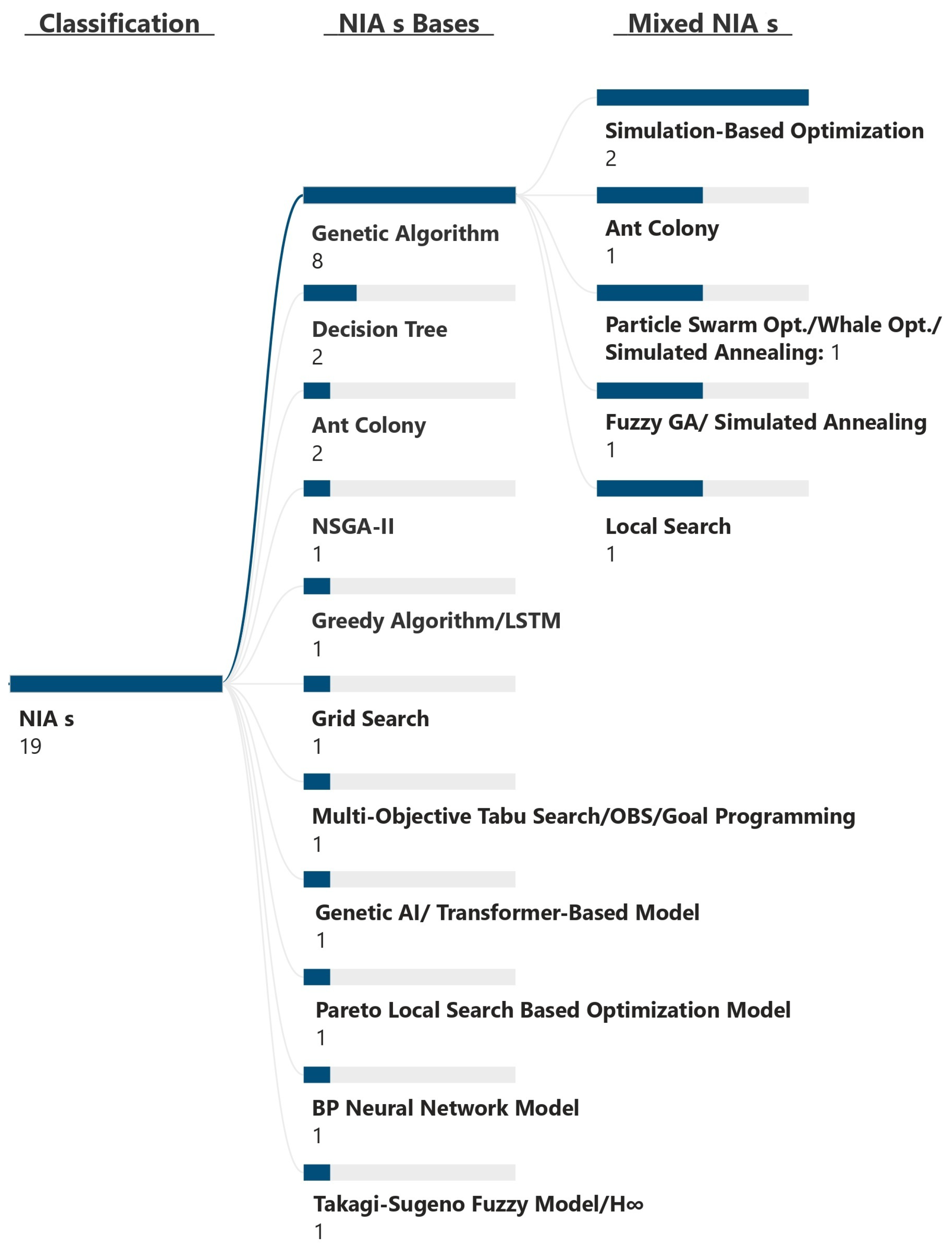

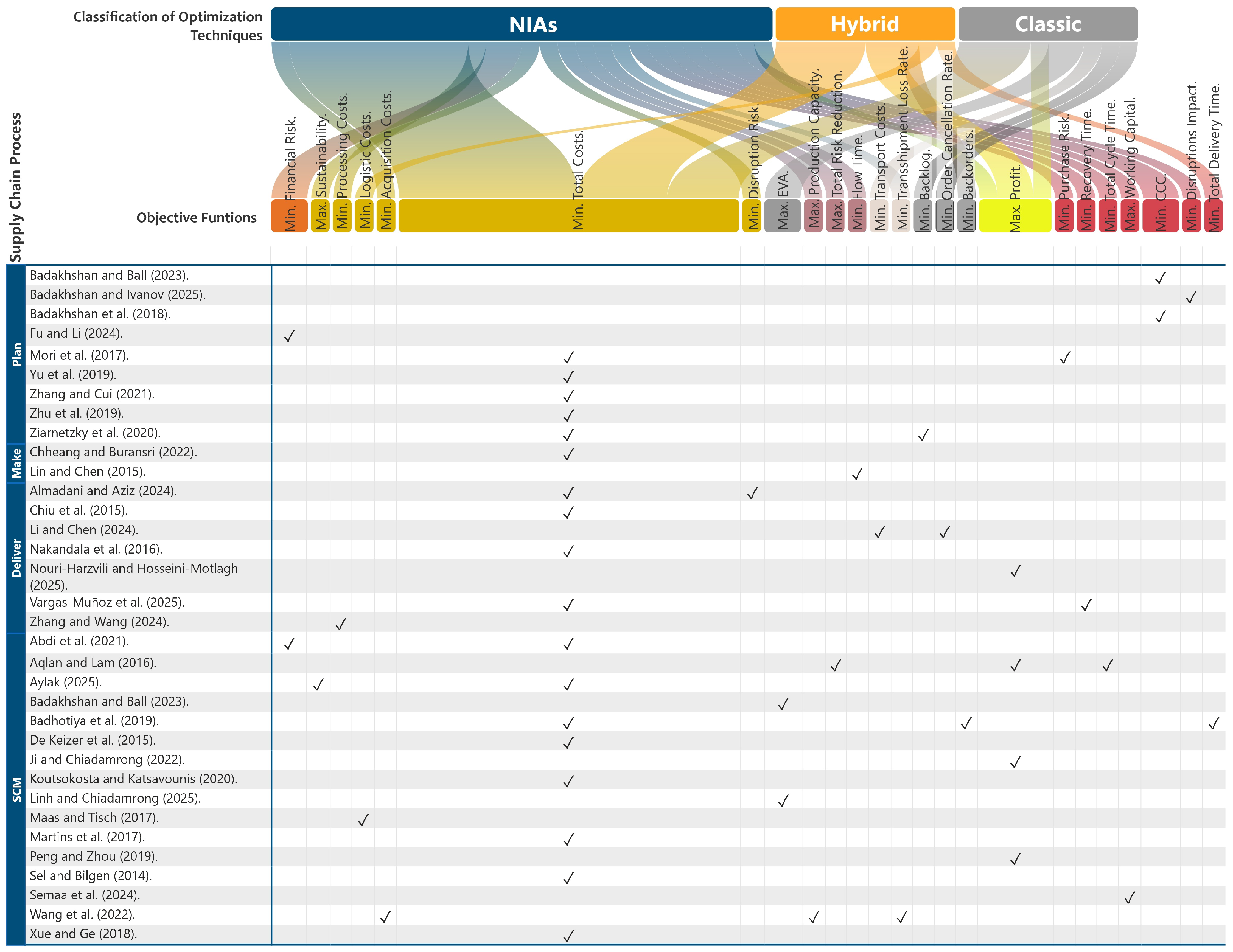

4.1. Optimization Techniques

4.2. Value Drivers

4.3. Supply Chain Processes

5. Research Gaps

- Lack of exploration of classical optimization techniques in economic performance: Overall, there is a significant opportunity to systematically apply and compare classical optimization techniques to complex problems that address economic performance and supply chain processes.

- Fragmentation and Limited Application of NIAs: Within the NIA category, there is a high fragmentation of techniques. The Genetic Algorithm is the most common, either individually or in combination, while the benefits of advanced artificial intelligence and optimization methods have yet to be explored for improving economic performance in supply chain contexts.

- Lack of Accessible and Interpretable Approaches in Resource-Constrained Contexts: Despite the growing sophistication of nature-inspired algorithms (NIAs), current research predominantly emphasizes complex techniques (such as genetic algorithms) without adequately addressing the operational constraints of small and medium-sized enterprises. These firms often lack the computational resources and technical expertise required to implement such methods, and instead demand solutions that are both cost-effective and interpretable. This gap suggests a need for future studies to explore rule-based heuristics (IF-THEN systems) and approximation methods tailored to financially constrained supply chain environments.

- Insufficient Focus on Strategic Financial Metrics: The predominant objective in the 35 works, regardless of the technique classification, is the Minimization of Total Costs or cost variants, neglecting more robust and strategic financial metrics such as EVA, the Cash Conversion Cycle, or Cash Flow.

- Lack of Models for Disruption and Resilience Scenarios: Although financial and disruption risk is mentioned, few models address it dynamically or adaptively. Thus, a gap exists in the design and development of predictive models that integrate digital twins, blockchain, and simulation to manage physical and financial disruptions in quasi real time.

- Imbalance in the Addressing of Supply Chain Processes: Regarding the relationship between supply chain processes, it is observed that the Plan, Make, Deliver, and SCM processes concentrate the majority of the works. And, although the SCM classification encompasses two or more supply chain processes, the Source and Return processes are underexplored—yet they are key processes in corporate financial metrics.

- Technological Maturity of Optimization Techniques: Finally, a formal assessment of the technological maturity of the identified optimization techniques would enable a distinction between mature applications and research frontiers. Such an evaluation could assist researchers in identifying emerging areas and help practitioners assess implementation risks and expected returns. Future studies may address this gap by combining literature reviews with commercial software analyses or industry surveys, aiming to map the maturity status of various optimization techniques applied to enhancing economic profitability within the supply chain.

6. Theorical and Practical Implications

6.1. Practical Implications

- Linking Decision Levels with Optimization Techniques: This review clarifies which families of optimization methods are most suitable for distinct decision-making levels (see Appendix A). Managers can observe that for strategic decisions aimed at maximizing robust metrics such as Economic Value Added (EVA), hybrid techniques—such as Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) combined with simulation—are particularly appropriate, as prior studies have already addressed these approaches. In contrast, for tactical or operational decisions focused on cost minimization, classical techniques remain both fundamental and effective

- Enhancing Economic Performance Beyond Cost Reduction: This study highlights the inherent complexity involved in aligning key strategic elements—such as value drivers—with supply chain processes. While cost reduction remains a commonly used metric to establish this connection, the review identifies additional supply chain activities and optimization techniques that can be leveraged to support the creation of economic value through operational processes.

- Consideration of Accessible Methods: This study reveals that current research predominantly focuses on advanced algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms and Deep Learning. This emphasis carries important implications for small and medium-sized enterprises, as it highlights the lack of lightweight methods (simple heuristics or IF-THEN rules) within high-impact literature. Such a gap not only suggests a promising direction for future research but also provides guidance for preparation and investment strategies among firms operating with limited resources.

- Focus on Investment in Technologies: This study identifies that certain rising technologies such as artificial intelligence, digital twins, and blockchain serve not only operational efficiency purposes but also represent valuable tools for managing financial resilience. This insight provides executives with a compelling rationale to invest in these technologies not merely as IT expenditures but as strategic assets for protecting working capital, fostering economic value creation, and mitigating financial risk.

6.2. Theorical Implications

- Moving Beyond Cost Minimization: This study identifies a theoretical need to transcend the prevailing cost-centric paradigm, signaling the maturation of the research field. The vast majority of the reviewed literature focuses on Total Cost Minimization or its variants essentially tactical metrics. In contrast, this work advocates for a shift in academic focus toward models that optimize strategic financial indicators capable of generating real economic value, such as Economic Value Added and the Cash Conversion Cycle.

- Integrating Operational and Financial Resilience: The study identifies a scarcity of models capable of dynamically managing disruptions. This implies that future theoretical frameworks should not only pursue operational robustness but also incorporate financial resilience that extends beyond cost and expenditure metrics. Such resilience should be enabled by key emerging technologies (such as digital twins, blockchain, artificial intelligence, and others) within the context of supply chain management.

- Contribution to the Economic Value Debate: This study expands the theoretical discourse on how logistics processes can be designed not only for operational efficiency but also for measurable economic value creation. Furthermore, it advocates for the exploration of rule-based heuristics, hybrid methods, and classical approaches capable of linking strategic indicators, such as Economic Value Added, with operational activities across the supply chain.

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations

- This study is constrained by its reliance on a single database. The literature search was conducted exclusively within the Web of Science database, which, while ensuring high-quality sources, systematically excluded potentially relevant studies indexed in other major repositories such as Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ProQuest, or EBSCO.

- Although the final 35 studies met the established inclusion criteria—namely, the presence of a financial objective function, the analysis of a supply chain process, and the application of an optimization technique—this review did not assess potential bias or the internal methodological quality of those studies. In other words, it is assumed that all 35 articles possess comparable methodological rigor, yet no formal evaluation was conducted to confirm this assumption.

- The classification of optimization techniques into Classical, Nature-Inspired Algorithms, and Hybrid approaches provides a clear structure grounded in the origin and nature of the methods. However, this framework may overlook other relevant classificatory dimensions. For instance, a secondary categorization based on the type of problem addressed (deterministic vs. stochastic) or the structure of the objective function (single-objective vs. multi-objective) could yield additional insights into the specific applicability scenarios of each technique family. The present review does not systematically explore these secondary dimensions within its primary classification framework, which may limit the reader’s ability to directly match specific problem types with the most suitable algorithm classes based on such structural characteristics.

- Another limitation of this study is the exclusion of non-English publications as well as studies focused on specific domains such as energy and transportation. It is possible that the excluded articles may contain relevant models or approaches that could enrich the findings and broaden the scope of analysis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCM | Supply Chain Management |

| NIAs | Nature-inspired algorithms |

| EVA | Economic Value Added |

| ROE | deváty |

| ROA | Return On Assets |

| NOPAT | Net Operating Profit After Tax |

| WACC | Weighted Average Cost of Capital |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| KKT | Karush–Kuhn–Tucker |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optmization |

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| ABC | Artificial Bee Colony |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| CCC | Cash Conversion Cycle |

| SBO | Simulation-Based Optimization |

| DES | Discrete Event Simulation |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

Appendix A

References

- Marmolejo-Saucedo, J.A. Digital Twin Framework for Large-Scale Optimization Problems in Supply Chains: A Case of Packing Problem. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2022, 27, 2198–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, S.; Mukhyi, M.A.; Veronica, D.; Ahyar, M.; Timisela, S.I. Corporate Financial Management, Risk Assessment, and Investment Strategies: Analyzing Their Effects on Business Sustainability. Glob. Int. J. Innov. Res. 2024, 2, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, M.; Ambroz, K. A Plea for Long-term Orientation in Organizations. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1303, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafuse, E.M. Working capital management an urgent need to refocus. Manag. Decis. 1996, 34, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padachi, K. Trends in Working Capital Management and Its Impact on Firms’ Performance: An Analysis of Mauritian Small Manufacturing Firms. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2006, 2, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, E.; Kotzab, H. A supply chain-oriented approach of working capital management. J. Bus. Logist. 2010, 31, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Martínez, D.; Acevedo-Suárez, A.; Amaro-Martínez, D. The integration of finance to logistic flow. Application: Feeding process. Ing. Ind. 2019, 40, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Świerczek, A. The impact of supply chain integration on the “snowball effect” in the transmission of disruptions: An empirical evaluation of the model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 157, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, R.; Shapir, O.M. Cash conversion cycle and value-enhancing operations: Theory and evidence for a free lunch. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 45, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toušek, Z.; Hinke, J.; Gregor, B.; Prokop, M. Vulnerability Within the Czech Automotive Supply Chain. Danube 2025, 16, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Ravipati, R. A Liquidity-Profitability Trade-Off Model for Working Capital Management. SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Triana, S.; Gutierrez, J.C.; Leon-Becerra, J. Integration of Machine Learning in the Supply Chain for Decision Making: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2024, 17, 344–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, J.A.C.; Junior, O.F.L.; Novaes, A.G.N.; Moreno, G.N.M. Supply chain integration in the industry 4.0 era: A systematic literature review. Braz. J. Dev. 2022, 8, 67536–67569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmolejo-Saucedo, J.A. Design and Development of Digital Twins: A Case Study in Supply Chains. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2020, 25, 2141–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Meindl, P.; Salas, R.N.; Elmer, J.; Murrieta, M.; Porras, E.; Montúfar Benítez, M.A. Administración de la Cadena de Suministro. Estrategia, Planeación y Operación, 5th ed.; Pearson Educación: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Slone, R.; Dittmann, P.J.; Mentzer, J.T. The New Supply Chain Agenda: The 5 Steps That Drive Real Value; Harvard Business Review Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 1, p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Agus, A. The Importance of Supply Chain Management on Financial Optimization. J. Tek. Ind. 2013, 15, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Rezaei, A.R.; Wong, K.Y.; Azami, M.M. Integrated modeling and optimization of material flow and financial flow of supply chain network considering financial ratios. Control Optim. 2019, 9, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehar, N. Decisions Making Based on Numerous Factors Improves Financial Management. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambly, B.; Xu, R.; Yang, H. Recent Advances in Reinforcement Learning in Finance. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2112.04553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H.; Pattanaik, L.N. Quantitative Optimization Models in Supply Chains: Taxonomy, Trends and Analysis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 3787–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S.; Choi, T.Y. Toward the theory of the supply chain. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2015, 51, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Analytics and Model-Based Decision-Making Support. In Introduction to Supply Chain Analytics: With Examples in AnyLogic and anyLogistix Software; Ivanov, D., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, R.R.; Pinto, J.K. Integrating Cost and Value in Projects. In Cost and Value Management in Projects; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, J.T. Fundamentals of Supply Chain Management: Twelve Drivers of Competitive Advantage; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Montoya, L.; MARGARITA PORTILLA Administradora Financiera, L.; Sc Profesor Auxiliar, M. TEORÍA ECONÓMICA CLÁSICA ACERCADA A LA ACTUALIDAD. Sci. Tech. 2009, XV, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dumrauf, G.L. Finanzas Corporativas: Un Enfoque Latinoamericano, 3rd ed.; Alfaomega Grupo Editor Argentino: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra García, M.L.; Saavedra García, M.J. Evolución y aportes de la teoría financiera y un panorama de su investigación en México: 2003–2007. Cienc. Adm. 2012, 2, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lizcano Álvarez, J.; Castelló Taliani, E. Rentabilidad Empresarial: Una Propuesta Práctica de Análisis y Evaluación; Cámaras de Comercio: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De La Hoz Suárez, B.; Ferrer, M.A.; De La Hoz Suárez, A. Indicadores de rentabilidad: Herramientas para la toma decisiones financieras en hoteles de categoría media ubicados en Maracaibo. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2008, 14, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppson, N.H.; Ruddy, J.A.; Salerno, D.F. The influence of social media usage on the DuPont method of analysis. J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2021, 32, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saus-Sala, E.; Farreras-Noguer, À.; Arimany-Serrat, N.; Coenders, G. Compositional DuPont Analysis: A Visual Tool for Strategic Financial Performance Assessment. In Advances in Compositional Data Analysis: Festschrift in Honour of Vera Pawlowsky-Glahn; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A.C.; West, T. Economic Value-Added: A Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature. Asian Rev. Account. 2001, 9, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limarev, P.V.; Petrov, A.; Zinovyeva, E.G.; Limareva, J.A.; Chang, R.I.S. “Added Economic Value” Calculation for the Higher Education Providers’ Services. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 272, 032147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.H. Dissecting Eva: The Value Drivers Determining the Shareholder Value of Industrial Companies. SSRN Electron. J. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluszcz, A.; Kijewska, A. Factors Creating Economic Value Added of Mining Company. Arch. Min. Sci. 2016, 61, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Sánchez, J.M. Introduction to modelling in mathematical programming. In Modelling in Mathematical Programming; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 298, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, W.L. Operations Research: Applications and Algorithms, 4th ed.; Brooks/Cole–Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Duraiappah, A.K. The Mathematical Model. In Global Warming and Economic Development; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzig, G.B. Maximization of a linear function of variables subject to linear inequalities. In Activity Analysis of Production and Allocation; Koopmans, T.C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1951; pp. 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig, G.B. Linear Programming. Oper. Res. 2002, 50, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic Programming; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1972; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K.L.; Ralphs, T.K. Integer and Combinatorial Optimization. In Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science; Gass, S.I., Fu, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.W.; Tucker, A.W. Nonlinear Programming. In Traces and Emergence of Nonlinear Programming; Giorgi, G., Kjeldsen, T., Eds.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D.G.; Ye, Y. Basic Properties of Linear Programs. In Linear and Nonlinear Programming; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsey, L.A. Formulations. In Integer Programming, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Wang, S. Integer optimization. In Applications of Machine Learning and Data Analytics Models in Maritime Transportation; Institution of Engineering and Technology: Stevenage, UK, 2022; pp. 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerapen, N.; Ochoa, G.; Harman, M.; Burke, E.K. An Integer Linear Programming approach to the single and bi-objective Next Release Problem. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.G.; Duong, N.H.; Mai, T.; Ta, T.A. Near-optimal Approaches for Binary-Continuous Sum-of-ratios Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2211.02152. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, C.S. Modeling Framework. In Model-Based Optimization for Petroleum Refinery Configuration Design; Wiley-VCH GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2024; pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birge, J.R.; Louveaux, F. Stochastic Integer Programs. In Introduction to Stochastic Programming, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.F.; Florentino, H.O. Multi-Objective Optimization: Methods and Applications. In The Palgrave Handbook of Operations Research; Salhi, S., Boylan, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrgott, M. Introduction to Multicriteria Linear Programming. In Multicriteria Optimization, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Optimality and Non-Scalar-Valued Performance Criteria. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1963, 8, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita-Cunha, M.; Figueira, J.R.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P. New ϵ—Constraint methods for multi-objective integer linear programming: A Pareto front representation approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Sahay, K.B.; Singh, R.K. Optimization Techniques in Modern Times and Their Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), Krabi, Thailand, 7–9 March 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Optimization Techniques in the Field of Engineering and Technology. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.K. A review of classical methods and Nature-Inspired Algorithms (NIAs) for optimization problems. Results Control Optim. 2023, 13, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloss, A.N.; Gustafson, S. 2019 Evolutionary Algorithms Review. In Genetic Programming Theory and Practice XVII; Banzhaf, W., Goodman, E., Sheneman, L., Trujillo, L., Worzel, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 307–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Kar, A.K. Swarm intelligence: A review of algorithms. In Modeling and Optimization in Science and Technologies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.; Abdelhamid, A.A.; Ibrahim, A. Metaheuristic Optimization Review: Algorithms and Applications. J. Artif. Intell. Metaheuristics 2023, 3, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE. IEEE Thesaurus; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.ieee.org/content/dam/ieee-org/ieee/web/org/pubs/ieee-thesaurus.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Clarivate. Web of Science Core Collection: Author Search Rules. Available online: https://support.clarivate.com/ScientificandAcademicResearch/s/article/Web-of-Science-Core-Collection-Author-Search-Rules?language=en_US (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.; Hoefnagels, R.; Junginger, M. Wood pellet supply chain costs—A review and cost optimization analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 118, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marak, Z.R.; Pillai, D. Factors, Outcome, and the Solutions of Supply Chain Finance: Review and the Future Directions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2019, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, M.J.; Gerber, R.; Goedhals-Gerber, L.L.; van Eeden, J. Shaping the Future of Freight Logistics: Use Cases of Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiah, E.T.; Meutia; Bastian, E.; Retnowati, W. Sustainable Logistics and Supply Chain Management through Environmental Management Accounting and Distribution Innovation: A Review. J. Distrib. Sci. 2024, 22, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.; Kolte, A.; Sangvikar, B.V.; Jain, S. Analysis of Reverse Logistics Functions of Small and Medium Enterprises: The Evaluation of Strategic Business Operations. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024, 25, 1129–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xiao, T.; Chai, C. Choice of Cost Reduction Mode in a Contract Manufacturing Supply Chain with Substitutable Products. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 4351–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambadapudi, H.; Matai, R. Benefits of a collaborative liquidity management approach: A simulation study for the Indian auto value chain. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 1795–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, A.; Liu, C.G.; Xu, Y.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, S. Untangling the cumulative impact of big data analytics, green lean six sigma and sustainable supply chain management on the economic performance of manufacturing organisations. Prod. Plan. Control 2025, 36, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotia, V.; Sharma, P.; Alofaysan, H.; Agarwal, V.; Mammadov, A. Fintech Adoption and Financial Performance: The Unrecognized Contributions of Supply Chain Finance and Supply Chain Risk. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, R.; Silva, C.; Costa, E. Eco-efficiency assessment in the agricultural sector: The Monte Novo irrigation perimeter, Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glišić, S.; Stamenković, P. PERCEPTION OF SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED HOTEL MANAGERS ON THE ECONOMIC FEASIBILITY OF PROCURING LOCAL AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS. Ekon. Poljopr. 2025, 72, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguedou, E.; Narra, S.; Afrakoma Armoo, E.; Agboka, K.; Kongnine Damgou, M. E-Technology Enabled Sourcing of Alternative Fuels to Create a Fair-Trade Circular Economy for Sustainable Energy in Togo. Energies 2023, 16, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Tang, J.; Pan, Z. Learning-Based Bundling Strategy for Two Products Under Uncertain Consumer’s Valuations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 1970–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibañez-Aguilar, J.E.; Guillen-Gosálbez, G.; Morales-Rodriguez, R.; Jiménez-Esteller, L.; Castro-Montoya, A.J.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Financial Risk Assessment and Optimal Planning of Biofuels Supply Chains under Uncertainty. Bioenergy Res. 2016, 9, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balussou, D.; Heffels, T.; McKenna, R.; Möst, D.; Fichtner, W. An evaluation of optimal biogas plant configurations in Germany. Waste Biomass Valorization 2014, 5, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egieya, J.M.; Čuček, L.; Zirngast, K.; Isafiade, A.J.; Pahor, B.; Kravanja, Z. Synthesis of biogas supply networks using various biomass and manure types. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2019, 122, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri Lavassani, K.; Iyengar, R.; Movahedi, B. Multi-tier analysis of the medical equipment supply chain network: Empirical analysis and simulation of a major rupture. Benchmarking 2023, 30, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, H.; Lai, K.K.; Ram, B. A City Logistics Distribution Model: A Physical Internet Approach. Processes 2023, 11, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boșcoianu, M.; Toth, Z.; Goga, A.S. Sustainable Strategies to Reduce Logistics Costs Based on Cross-Docking—The Case of Emerging European Markets. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cai, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Zeng, H. The optimization of reverse logistics cost based on value flow analysis—A case study on automobile recycling company in China. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 34, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyashevich, I.P. Optimization of the order size concerning losses from the immobilization of working capital in the reserves of material resources. Econ. Math. Methods 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulah, A.; Rajadurai, K.R.; Anitha, T.; Rajangam, J.; Maanchi, S. Postharvest handling and value added products of tomato to enhance the profitability of farmers. Plant Sci. Today 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.; Meyer, P. Electrifying the Last-Mile Logistics (LML) in Intensive B2B Operations—An European Perspective on Integrating Innovative Platforms. Logistics 2024, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, S.; Abdulqader, H.; Al Wahedi, Y.; Berrouk, A.S. Countrywide optimization of natural gas supply chain: From wells to consumers. Energy 2020, 196, 117125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Martins, P. Integrating Weather and Orography Information in Trip Planning Systems for Heavy Goods Vehicles. In New Trends in Disruptive Technologies, Tech Ethics and Artificial Intelligence; de la Iglesia, D.H., de Paz Santana, J.F., López Rivero, A.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Pei, X.; Xu, P.; Yue, Y.; Han, C. Reinforcement Learning-Driven Intelligent Truck Dispatching Algorithms for Freeway Logistics. Complex Syst. Model. Simul. 2024, 4, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C.; Tisch, A.; Intra, C.; Fottner, J. Integrated Optimization of Transportation and Supply Concepts in the Automotive Industry. In Proceedings of the 31st European Conference on Modelling and Simulation (ECMS 2017); Zoltay Paprika, Z., Horák, P., Váradi, K., Zwierczyk, P.T., Vidovics-Dancs, Á., Rádics, J.P., Eds.; European Council for Modeling and Simulation: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chheang, H.; Buransri, N. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Model for Stochastic Capacitated Lot-Sizing Problem Under Static-Dynamic Uncertainty Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications, DASA, Chiangrai, Thailand, 23–25 March 2022; pp. 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shah, N.; Carré, G.; Lemaire, S.; Gatignol, E.; Piccione, P.M. Continent-wide planning of seed production: Mathematical model and industrial application. Optim. Eng. 2019, 20, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsokosta, A.; Katsavounis, S. A Dynamic Multi-Period, Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Model for Cost Minimization of a Three-Echelon, Multi-Site and Multi-Product Construction Supply Chain. Logistics 2020, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhotiya, G.K.; Soni, G.; Mittal, M.L. Fuzzy multi-objective optimization for multi-site integrated production and distribution planning in two echelon supply chain. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.W.; Huang, C.C.; Chiang, K.W.; Wu, M.F. On intra-supply chain system with an improved distribution plan, multiple sales locations and quality assurance. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri-Harzvili, M.; Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M. Optimizing Discount Offers in Online Retail Marketplaces: Roles of Inventory and Goodwill Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhou, Z. Working capital optimization in a supply chain perspective. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 277, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, E.; Ball, P. A simulation-optimization approach for integrating physical and financial flows in a supply chain under economic uncertainty. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2023, 10, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, T.T.U.; Chiadamrong, N. Maximizing EVA in a Cocoa Supply Chain Network Design with a Hybrid Optimization Approach: A Case Study in Vietnam. Eng. J. 2025, 29, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Chiadamrong, N. Integrating Mathematical and Simulation Approach for Optimizing Production and Distribution Planning With Lateral Transshipment in a Supply Chain. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Supply Chain. Manag. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keizer, M.; Haijema, R.; Bloemhof, J.M.; Van Der Vorst, J.G. Hybrid optimization and simulation to design a logistics network for distributing perishable products. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 88, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Amorim, P.; Figueira, G.; Almada-Lobo, B. An optimization-simulation approach to the network redesign problem of pharmaceutical wholesalers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 106, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sel, Ç.; Bilgen, B. Hybrid simulation and MIP based heuristic algorithm for the production and distribution planning in the soft drink industry. J. Manuf. Syst. 2014, 33, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarnetzky, T.; Mönch, L.; Uzsoy, R. Simulation-Based Performance Assessment of Production Planning Models with Safety Stock and Forecast Evolution in Semiconductor Wafer Fabrication. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2020, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T. ISCCO: A deep learning feature extractionbased strategy framework for dynamic minimization of supply chain transportation cost losses. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaa, H.; Semma, A.; Bouzarra, L.; Kerrouch, H.; Semma, Z.; Hou, M.A. Assessing the Efficacy of Genetic Algorithm-Based Heuristics in Optimizing Working Capital Through Flexible Cash Receipt Scheduling. In Proceeding of the 7th International Conference on Logistics Operations Management, GOL’24; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1105, pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Ge, L. Cost Optimization Control of Logistics Service Supply Chain Based on Cloud Genetic Algorithm. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 3171–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadani, K.S.; Aziz, N.A.B. Modelling a Dual-Objective Optimization Model for Cost Reduction and Disruption Risk Minimization in Automotive Supply Chains. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2024, 20, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakandala, D.; Lau, H.; Ning, A. A hybrid approach for cost-optimized lateral transshipment in a supply chain environment. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2016, 22, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Abdi, A.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. A set of calibrated metaheuristics to address a closed-loop supply chain network design problem under uncertainty. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2021, 8, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakandala, D.; Lau, H.; Zhang, J. Cost-optimization modelling for fresh food quality and transportation. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; Chen, C.M. Simulation optimization approach for hybrid flow shop scheduling problem in semiconductor back-end manufacturing. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2015, 51, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. A Dynamic Scheduling Method for Logistics Supply Chain Based on Adaptive Ant Colony Algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Li, H. Application of BP neural network model in supply chain financial risk control. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2024, 20, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, E.; Ball, P. Applying digital twins for inventory and cash management in supply chains under physical and financial disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 5094–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, E.; Ivanov, D. Integrating digital twin and blockchain for responsive working capital management in supply chains facing financial disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 7800–7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hou, G.; Xia, P.; Li, J. Supply chain joint inventory management and cost optimization based on ant colony algorithm and fuzzy model. Teh. Vjesn. 2019, 26, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Muñoz, J.C.; Sanchez-Nitola, F.A.; Adarme Jaimes, W.; Rios, R. Enhancing Logistical Performance in a Colombian Citrus Supply Chain Through Joint Decision Making: A Simulation Study. Logistics 2025, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqlan, F.; Lam, S.S. Supply chain optimization under risk and uncertainty: A case study for high-end server manufacturing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 93, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylak, B.L. SustAI-SCM: Intelligent Supply Chain Process Automation with Agentic AI for Sustainability and Cost Efficiency. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Z. Supply Chain Optimization Strategy Research Based on Deep Learning Algorithm. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 9058490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, Y. Research on Robust Financing Strategy of Uncertain Supply Chain System Based on Working Capital. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, E.; Humphreys, P.; Maguire, L.; McIvor, R. Simulation-based system dynamics optimization modelling of supply chain working capital management under lead time uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Funchal, Portugal, 25–27 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Kobayashi, R.; Samejima, M.; Komoda, N. Risk-cost optimization for procurement planning in multi-tier supply chain by Pareto Local Search with relaxed acceptance criterion. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 261, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Base Word | Thesaurus |

|---|---|

| Supply Chain | Supply Chain, logistics, supply network, value chain. |

| Economic Profitability | Financial performance, cost reduction, cost optimization, revenue generation, profitability, working capital, liquidity, financial risk, cash flow, return on investment, ROI. |

| Optimization Technique | Mathematical model, optimization, optimisation, algorithm, simulation, predictive model, data analytic, machine learning, deep learning, artificial intelligence, stochastic model, control theory, game theory, network model, forecasting model, statistical model computational method, quantitative method. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jarquin-Segovia, R.; Marmolejo-Saucedo, J.A. Optimization Techniques for Improving Economic Profitability Through Supply Chain Processes: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics 2026, 14, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010185

Jarquin-Segovia R, Marmolejo-Saucedo JA. Optimization Techniques for Improving Economic Profitability Through Supply Chain Processes: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010185

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarquin-Segovia, Ricardo, and José Antonio Marmolejo-Saucedo. 2026. "Optimization Techniques for Improving Economic Profitability Through Supply Chain Processes: A Systematic Literature Review" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010185

APA StyleJarquin-Segovia, R., & Marmolejo-Saucedo, J. A. (2026). Optimization Techniques for Improving Economic Profitability Through Supply Chain Processes: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics, 14(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010185