Spatiotemporal Pattern Selection in a Modified Leslie–Gower Predator–Prey System with Fear Effect and Self-Diffusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- Fear shifts the location of the codimension-2 Bogdanov–Takens cusp in the temporal system, generating enhanced multistability with up to six equilibria (Section 3).

- (ii)

- Fear raises the critical predator diffusion coefficient required for Turing instability and modulates the wavelength of emergent patterns (Section 4).

- (iii)

2. Equilibria and Their Properties of the Temporal System

- (1)

- if , is a saddle-node;

- (2)

- if and , is a cusp of codimension-2 (see Figure 2).

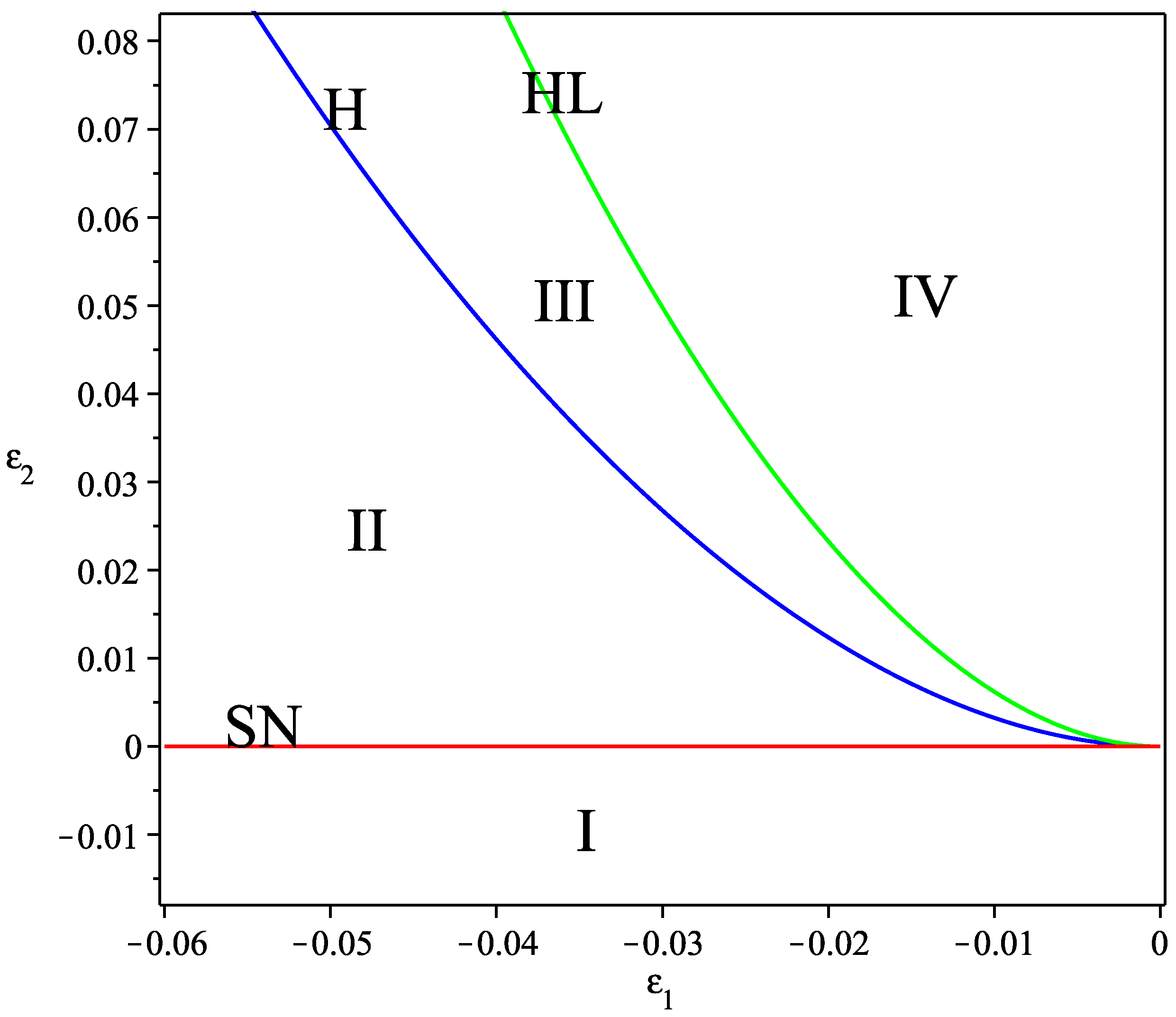

3. Bogdanov–Takens Bifurcation Analysis of the Temporal System

- (1)

- The saddle-node bifurcation curve SN ;

- (2)

- The Hopf bifurcation curve H ;

- (3)

- The homoclinic bifurcation curve

4. Dynamics of the Spatiotemporal System

5. Amplitude Equations

- (i)

- Steady state: ; it is stable as and is unstable when .

- (ii)

- Stripe pattern: ; it is stable when and is unstable when .

- (iii)

- Spot pattern:Its existence condition is . The solution is stable as , while is always unstable, where

- (iv)

- Mixed structural state: . It exists when and is always unstable as The explicit thresholds areThe bifurcation diagram of Turing patterns is given in Figure 7. These analytical predictions are fully confirmed by direct numerical simulations of the original system (4) in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Lotka, A.J. Analytical note on certain rhythmic relations in organic systems. Biol. Sci. 1921, 6, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volterra, V. Variazionie fluttuazioni del numero d’individui in specie animali conviventi. Mem. R. Accad. Naz. Lincei 1923, 6, 31–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Banerjee, M. Hopf and steady state bifurcation analysis in a ratio-dependent predator-prey model. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017, 44, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Yang, P.; Luo, Z.L.; Lin, Y.P. Bogdanov-Takens bifurcation in a delayed Michaelis-Menten type ratio-dependent predator-prey system with prey harvesting. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2019, 9, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.P.; Cao, H.J. Stability and bifurcation analysis in a predator-prey system with Michaelis-Menten type predator harvesting. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2017, 33, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Ruan, S.G.; Xiao, D.M. Bifurcations analysis of a mosquito population model with a saturated release rate of sterile mosquitoes. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2019, 18, 939–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.T.; Zhao, M.; Huang, K.L. Bifurcation analysis and simulations of a modified leslie-gower predator-prey model with constant-type prey harvesting. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 18789–18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Alaoui, M.A.; Daher Okiye, M. Boundedness and global stability for a predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower and Holling-type II schemes. Appl. Math. Lett. 2003, 16, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.T.; Huang, K.L.; Li, C.P. Bifurcation analysis of a modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey system. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2023, 33, 2350024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.L.; Jia, X.T.; Li, C.P. Analysis of modified Holling-Tanner model with strong allee effect. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 15524–15543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M. Effect of a protection zone in the diffusive Leslie predator-prey model. J. Differ. Equ. 2009, 246, 3932–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K. Existence and global attractivity of positive periodic solutions for a predator-prey model with modified Leslie-Gower Holling-type II schemes. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2011, 384, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.P.; Chandra, P. Bifurcation analysis of modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with Michaelis-Menten type prey harvesting. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2013, 398, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, H.; Luo, D. The effects of harvesting on the dynamics of a Leslie-Gower model. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 5520758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanette, L.Y.; White, A.F.; Allen, M.C.; Clinchy, M. Perceived predation risk reduces the number of offspring songbirds produce per year. Science 2011, 334, 1398–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salti, N.; Al-Musalhi, F.; Gandhi, V.; Al-Moqbali, M.; Elmojtaba, I. Dynamical analysis of a prey-predator model incorporating a prey refuge with variable carrying capacity. Ecol. Complex. 2021, 45, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, W. Predation in bird populations. J. Ornithol. 2011, 152, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zanette, L.; Zou, X. Modelling the fear effect in predator-prey interactions. J. Math. Biol. 2016, 73, 1179–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P.P.; Fan, M.; Zou, X.F. Dynamics of a three-species food chain model with fear effect. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2021, 99, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S.K. Population dynamics with multiple Allee effects induced by fear factors-A mathematical study on prey-predator interactions. Appl. Math. Model. 2018, 64, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Tan, Y.P.; Cai, Y.L.; Wang, W.M. Impact of the fear effect on the stability and bifurcation of a Leslie-Gower predator-prey model. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Banjerdpongchai, D.; Park, P. Stability and Hopf-bifurcation analysis of diffusive Leslie-Gower prey-predator model with the Allee effect and carry-over effects. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 227, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, S.; Vadivel, R.; Hu, N.T.; Chen, C.S.; Gunasekaran, N. Bifurcation Analysis in a Harvested Modified Leslie-Gower Model Incorporated with the Fear Factor and Prey Refuge. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoth, S.; Sivasamy, R.; Sathiyanathan, K.; Unyong, B.; Rajchakit, G.; Vadivel, R.; Gunasekaran, N. The dynamics of a Leslie type predator-prey model with fear and Allee effect. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, 2021, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Zhang, J.F. Dynamic complexity of a modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey system with fear effect. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2023, 119, 107109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Momen, S.; Naji, R.K. The dynamics of modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey model under the influence of nonlinear harvesting and fear effect. Iraqi J. Sci. 2022, 63, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 1952, 237, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausmeier, C.A. Regular and irregular patterns in semiarid vegetation. Science 1999, 284, 1826–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.C.; Hohenberg, P.C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Petrovskii, S. Self-organised spatial patterns and chaos in a ratio-dependent predator-prey system. Theor. Ecol. 2011, 4, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshu; Dubey, B.; Kumar Sasmal, S.; Sudarshan, A. Consequences of fear effect and prey refuge on the Turing patterns in a delayed predator-prey system. Chaos 2022, 32, 123132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Kesh, D.; Mukherjee, D. Qualitative study of cross-diffusion and pattern formation in Leslie–Gower predator–prey model with fear and Allee effects. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 167, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.N.; Li, C.Z.; Wang, D. Normal Forms and Bifurcation of Planar Vector Fields; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, L. Differential equations and dynamical systems. In Texts in Applied Mathematics, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Asai, R. A reaction-diffusion wave on the skin of the marine angelfish pomacanthus. Nature 1995, 376, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, R.A.; Wollkind, D.J.; Kealy-Dichone, B.J.; Chaiya, I. Nonlinear stability analyses of Turing patterns for a mussel-algae model. J. Math. Biol. 2015, 70, 1249–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrots, A.; Langlais, M. A singular reaction-diffusion system modelling prey-predator interactions: Invasion and co-extinction waves. J. Differ. Equ. 2012, 253, 502–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherratt, J.A.; Eagan, B.T.; Lewis, M.A. Oscillations and chaos behind predator-prey invasion: Mathematical artifact or ecological reality. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 1997, 352, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Biology Interpretation |

|---|---|

| r | Birth rates of the prey |

| s | Birth rates of the predator |

| k | Environment carrying capacity of the prey |

| M | Strength of Allee effect on the prey |

| m | Environmental protection on both species |

| The consumption rate of the prey | |

| Competition coefficient | |

| Diffusion rate of the prey | |

| Diffusion rate of the predator |

| Pattern | ||

|---|---|---|

| 5.5 | Spot | |

| 7 | Mixed (Spot and Stripe) | |

| 16 | Stripe |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jia, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Huang, K. Spatiotemporal Pattern Selection in a Modified Leslie–Gower Predator–Prey System with Fear Effect and Self-Diffusion. Mathematics 2026, 14, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010190

Jia X, Zhao L, Zhang L, Huang K. Spatiotemporal Pattern Selection in a Modified Leslie–Gower Predator–Prey System with Fear Effect and Self-Diffusion. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010190

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Xintian, Lingling Zhao, Lijuan Zhang, and Kunlun Huang. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Pattern Selection in a Modified Leslie–Gower Predator–Prey System with Fear Effect and Self-Diffusion" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010190

APA StyleJia, X., Zhao, L., Zhang, L., & Huang, K. (2026). Spatiotemporal Pattern Selection in a Modified Leslie–Gower Predator–Prey System with Fear Effect and Self-Diffusion. Mathematics, 14(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010190