1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the most significant areas of technological development, built on three main components: devices, networks, and controls. This complex system requires not only the development of each component but also the evaluation of conditions for their coexistence. A critical aspect of this task is assessing communication networks regarding the feasibility of control implementation. Since control decisions rely heavily on device feedback, the relevance and timeliness of this information are paramount. As information relevance depends on delivery speed and reliability, careful network-level analysis is required for various systems.

The Age of Information (AoI) has been proposed as a formal metric to evaluate update freshness [

1]. In continuous-time systems, the AoI is defined as the time elapsed since the generation of the last successfully delivered update. Additionally, the discrete-time process formed by the local maxima of the AoI is analyzed to evaluate the delivery timeliness. This metric, known as the Peak AoI (PAoI), is defined as the sum of the inter-arrival time and the sojourn time for each update [

1]. By exploring the AoI and PAoI, it is possible to assess the freshness of the information and optimize the network to ensure timely updates.

A leading recent technology enabling URLLC for energy-efficient devices using machine-type communication (MTC) is Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications New Radio (DECT-2020 NR), developed by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) [

2]. The DECT-2020 is designed to operate over a mesh topology with multi-hop transmission. It is applicable in scenarios such as Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANET) [

3,

4], Maritime Wireless Networks (MWN) [

5], professional audio systems [

6], and so on [

7,

8].

Specifically, we model the network layer behavior of a DECT-2020 link, abstracting the underlying TDMA frame structure and HARQ mechanisms into stochastic service times. A detailed mapping of these system features to the queueing model parameters is provided in

Section 3.

Consequently, a tandem queueing model is an effective representation of such systems, as updates traverse multiple processing stages before reaching their destination. In this paper, we focus on analyzing the PAoI in a tandem queueing model. Specifically, we study the system, characterized by Poisson arrivals and exponential service times.

The research problem addressed in this paper is the derivation of the exact distribution properties (LST and moments) of the Peak Age of Information in a two-phase tandem network with random service times and the quantification of how service time variance affects information freshness.

The primary contribution of this work includes the following:

A detailed theoretical framework for computing PAoI using Laplace–Stieltjes transforms (LST), accounting for four mutually exclusive events based on the state of the system at the arrival of an update.

Derivation of analytical expressions for PAoI in the exponential case, specifically moments of PAoI.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the recent advances in AoI and PAoI analysis for tandem queueing systems.

Section 3 formalizes the mathematical model.

Section 4 details the proposed PAoI framework and underlying theorems. This framework is applied in

Section 5 to derive the PAoI LST for the exponential two-phase tandem system, followed by the derivation of moments in

Section 6. Numerical analysis is presented in

Section 7, and the paper concludes with a discussion in the final section.

2. Tandem Queueing System Related Work

The analysis of AoI in tandem with multiple exponential queueing systems with queue capacities equal to 1 was established by Kam and Molnar [

9], who derived expressions for the average AoI using a stochastic hybrid systems (SHS) model. Their work revealed the dependence of AoI metrics on the number of queues and service rates, providing guidelines for minimizing the AoI in such configurations. SHS was also employed in [

4] to assess the average AoI in an

network representing a VANET system.

Later, Kam [

10] derived the mean AoI for an exponential tandem system with two infinite-capacity queues and equal service rates using a graphical approach. The same system is used in [

3] as a VANET model. Here, the authors also utilize a graphical approach to obtain the average AoI.These results provide deep insights into VANETs, as the model incorporates wireless signal propagation and device placement parameters. Sinha et al. [

11] expanded on these ideas by introducing a recursive framework to calculate the PAoI in tandem systems with memoryless arrivals, variable service policies, and bufferless servers. This work highlighted the impact of preemptive and non-preemptive service disciplines on PAoI.

Recent studies have explored more nuanced aspects of tandem queueing systems. Chiariotti et al. [

12] investigated PAoI distributions in tandem queues

and

, emphasizing the relevance in satellite communication systems with relay nodes. Their results provided insights into the probabilistic characteristics of PAoI, extending beyond the mean values. Another notable contribution is by Koukoutsidis [

13], who examined the AoI in overtaking-free networks of quasi-reversible tandem queues, deriving expressions for multiple

First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) systems. Champati et al. [

14] considered a tandem of multiple FCFS queues with constant update generation times and independent random service times. The authors examined the AoI violation probability and optimized its upper bound. In [

15], the unreliable exponential tandem queueing system and the tandem of unreliable bufferless services with a general distributed service time were considered. For both models, the authors obtained the LSTs of the AoI by deriving them from the LSTs of the sojourn times.

Studies [

16,

17,

18] consider featured tandem systems that capture an edge computing-enabled network. Specifically, the authors of [

16] assume that the first stage of processing corresponds to computing and is carried out by a power-efficient and, hence, unreliable server. The second stage relates to transmission. It is executed for updates that do not exceed the deadline, and the buffer, where such updates are stored, has a unit-capacity. In this study, the input flow is assumed to be Poisson, the service time for the first stage is generally distributed, and the service time for the second stage follows an exponential distribution. The authors derive the average AoI and PAoI, and optimize the update deadline value.

The authors of [

17,

18], on the other hand, let the first server stage represent the transmission from the end device to the fog/edge server, and the second stage corresponds to the computing service. They also assume Poisson arrivals, exponentially distributed service times, and unlimited FCFS queues. As an additional feature, the authors of [

18] consider a scenario in which the end device does not generate updates if the current one is not being transmitted. Moreover, they analyze a system with additional input for the second stage. The authors examine a timeliness of information metric, which is defined similarly to the AoI. They propose a framework for timeliness of information minimization by optimizing the task generation, bandwidth allocation, and computation resource allocation.

In [

17], a model of partial computation is examined in which packets are processed partially on end devices and partially on edge servers. The study considers multiple sources, single transmission unit, and multiple receivers, where the last processing is performed. The authors derive the mean AoI by combining a graphical approach with a method that involves dividing packets into mutually exclusive groups; in the present paper, a variation of this method is used. They then optimize the fraction of processing performed on the end devices to minimize the mean AoI.

This review highlights the importance of AoI and PAoI analysis in exponential tandem queueing systems, which model a wide range of communication networks. However, most existing works focus on average characteristics rather than full distributions, such as Cumulative Distribution Functions (CDFs), which are necessary for flexible optimization and more nuanced performance insights. Addressing the PAoI PDF in an queue tandem will expand the range of available tools for system analysis and provide insights into the performance of state-update systems with two-stage processing.

3. Model Formalization

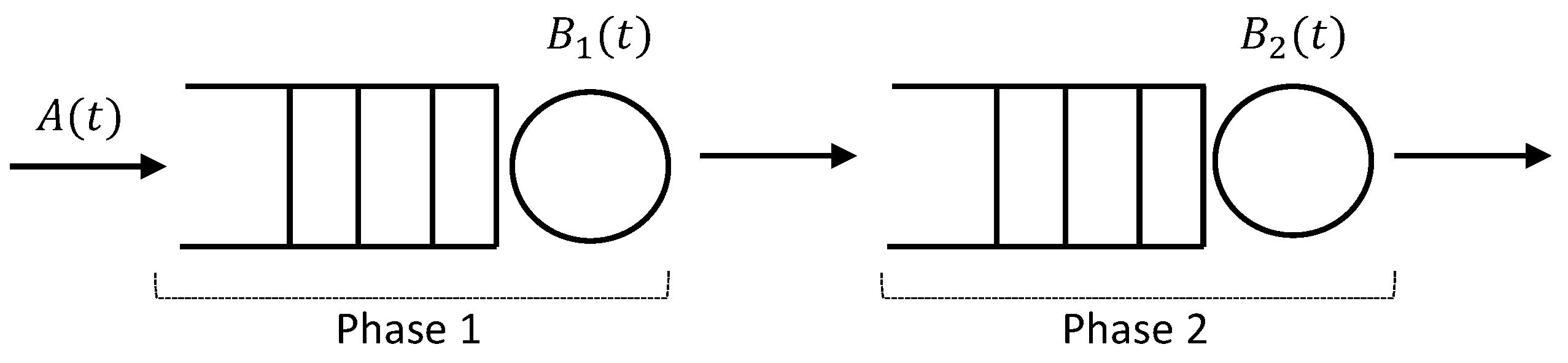

We consider a system in which every update consecutively passes through two sequential service phases, denoted as phase 1 and phase 2. In phase

j (

), an update waits in an infinite-capacity FCFS queue before being processed for an exponentially distributed service time

, with CDF

and LST

. We assume that the inter-arrival time of updates, denoted by

G, is exponentially distributed with CDF

and LST

. Hence, we note that each phase is a queueing system

, and we illustrate the considered tandem in

Figure 1.

For the analysis of the system, we will use the following random variables.

: the waiting time experienced by an update in phase j, with the CDF and LST .

: the waiting time in phase j, conditional on the server being busy on arrival of the update, with CDF and LST .

: the sojourn time (total time spent) in phase j, defined as ; its CDF and LST are denoted as and , respectively.

: the sojourn time in phase j, conditional on the server being busy upon the update’s arrival, with CDF and LST .

The purpose of the paper is to examine the PAoI

Z, defined as the sum of the generation and sojourn times of an update, i.e.,

The primary challenge in direct PAoI analysis is the dependence among its components

G,

, and

[

1]. To overcome this, we analyze the conditioned PAoI for four mutually exclusive update groups and combine them using the Law of Total Probability.

To justify the applicability of the

model to the DECT-2020 NR system, we consider the abstraction of the physical and MAC layer processes shown in

Table 1.

While the physical medium is time-slotted, the variations in channel quality, retransmissions (up to several frames), and scheduling wait times result in a randomized service interval at the application layer, which we approximate as exponential for analytical tractability.

4. Conditioned PAoI Framework

Let the number of updates in the j-th phase be denoted by , and introduce four outcomes indicating the state of the server (idle or busy):

: The first server is idle, i.e., there are no updates in the first phase (). The probability of this event is .

: The first server is busy, meaning that there is at least one update in the first phase (). The probability of this event is .

: The second server is idle, i.e., there are no updates in the second phase (). The probability of this event is .

: The second server is busy, meaning that there is at least one update in the second phase (). The probability of this event is .

We categorize the updates into mutually exclusive groups based on the system state observed upon arrival at the corresponding phases:

Updates observing both servers busy upon arrival to the appropriate phase, i.e., updates observing state (or event) , implying outcomes and .

Updates observing server 1 busy and server 2 idle, i.e., updates observing state (or event) , implying outcomes and .

Updates observing server 1 idle and server 2 busy, i.e., updates observing state (or event) , implying outcomes and .

Updates observing both servers idle, i.e., updates observing state (or event) , implying outcomes and .

We denote by the PAoI for updates from the i-th group, and we denote its LST by . For PAoI calculations, the four mutually exclusive events , , each leading to corresponding combinations of outcomes and , require separate consideration of the conditional probability distributions for the busy and idle server states. For these considerations, we will use the previously introduced random variables for the waiting time and the sojourn time of an update in the j-th phase, conditional on the server being busy.

The conditions for an update to observe states (events)

–

, together with the conditioned PAoI formulas, are described in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 2.

To clarify the classification of updates into these four groups, we present the decision logic in

Figure 3. This tree illustrates how the state of the servers observed by an arriving update determines the specific PAoI components.

The probabilities of events are derived based on their conditions and the independence of the involved random variables. Their detailed derivation is given below.

The derivation of these probabilities relies on the fundamental properties of tandem

queues. According to Burke’s Theorem [

19], the departure process of the first stable

queue is a Poisson process with rate

. Consequently, the second queue behaves as an independent

system in equilibrium. Furthermore, Reich’s Theorem [

20] establishes that the sojourn times

and

of a customer in a tandem of exponential queues are mutually independent. These properties justify the factorization of probabilities involving

,

, and the service times.

For event

, where an incoming update finds both servers busy (

, and

):

Using the independence of

G,

,

, and

, this can be expressed as

Then, evaluating

and

we obtain

Finally, expressing

and

in terms of the probability density function (PDF), we get

The remaining values

, can be obtained by applying the procedure described above. Then,

are calculated using the Formulas (

3)–(5).

Now, combining all conditional PAoI-obtained , we obtain an LST of PAoI Z in the following theorem.

Theorem 1. The LST of PAoI in the tandem queueing system is calculated using the formulawhere —LST of PAoI for the updates observing event upon arrivals to queues, . It should be noted that the described framework can be applied in more complicated networks, such as .

5. LST of PAoI in

To derive the LST of the PAoI, we proceed as follows:

Determine the conditional LSTs of waiting and sojourn times for busy/idle states (Lemma 1).

Calculate the probabilities of the four mutually exclusive events – (Lemma 2).

Combine these components using the law of total probability (Theorem 2) to obtain the final closed-form expression.

In this section, we apply Theorem 1 to obtain the LST of the PAoI in an

tandem queue and subsequently derive expressions for the PAoI mean and variance. To this end, we first find

, letting the rate of input flow be denoted by

and the service times rates be denoted by

and

, respectively. We assume

and

to ensure the system is ergodic and a stationary distribution exists. Recall that the LSTs for generation and service times are given by

The loads for each server are defined as

where

to ensure the stability of the system.

To determine , we utilize the following lemma:

Lemma 1. The LST of is expressed as Proof. Let the probability that there are

k updates in the queue during the

j-th phase be

. The previously introduced probability is that the server being busy in phase

j is

, while the probability that the server being idle is

. Consequently, the conditional probability

that there are exactly

k updates in the system (

for phase

j) during phase

j, given that the server is busy, is given by

Note that

, as it is impossible for the system to be empty under the condition that it is busy.

The CDF

of the random variable

, representing the waiting time in phase

j, can be expressed using the law of total probability and the unconditional probability distribution

, as

where

denotes the

j-fold convolution of the service time distribution at phase

j. Consequently, the LST of

is

Similarly, the CDF of

, representing the waiting time in phase

j under the condition of arrival to a busy system, can be expressed using the conditional probability distribution

, as

and its LST is given by

From this, we derive

□

With the LST of the waiting time under the condition of arrival to a busy system determined, the LST of the sojourn time under the same condition can be easily derived as

As a result, for the exponential tandem queueing system, we obtain

For implementing Theorem 1, we specify using the following Lemma.

Lemma 2. For the exponential tandem queueing system , the probabilities of events defined by (2)–(5) have the form of Finally, we present the following theorem determining the form of the PAoI LST, .

Theorem 2. The LST is given by Since the derived LST

in Theorem 2 is a rational function of

s, the Probability Density Function (PDF)

can be obtained exactly via the inverse Laplace transform. We rewrite

as a ratio of polynomials:

where the constant

, the numerator polynomial

, and the characteristic polynomial

are defined as

The roots of

correspond to five distinct poles of the system:

Using the Residue Theorem for distinct poles, the PDF is a sum of exponential functions:

The coefficients (residues)

are calculated analytically by

This formula provides the exact distribution of PAoI, enabling the direct calculation of tail probabilities without numerical inversion.

6. Moments of PAoI

The moments of the PAoI can be derived from its Laplace–Stieltjes Transform (LST),

, using the standard moment-generating properties of the LST. The

n-th moment is given by

In particular, for the mean and the second moment, we have the following identities:

Using the expressions obtained, we can find the mean value of the PAoI

Next, we find the expression of the second moment, for which, we explicitly express the derivatives of the PAoI LST

. The first derivative is expressed as

and the second derivative will take the form

The second moment

of the PAoI is expressed as

Thus, we have the following expressions for the first and second moments of the PAoI in a tandem queueing system

from which, we can express the variance

and standard deviation

of PAoI.

As a quick self-check, we can examine the first two Taylor series terms of the LST

around

. A Taylor expansion yields

where

and

are given by (

30) and (

31), respectively. Substituting the expressions for

and

confirms the consistency of our derived LST.

To minimize the average Peak Age of Information, we formulate the optimization problem with respect to the arrival rate

, subject to the stability condition

. The objective function is defined by Equation (

30):

To find the critical points, we take the derivative with respect to

and set it to zero:

Rearranging terms, we isolate the arrival rate component:

Multiplying by

to clear the denominators yields

Let

, and

. Expanding both sides reveals that the fourth-order terms

and the third-order terms

on both sides cancel out. The resulting equation simplifies to a depressed quartic polynomial:

Substituting back

and

, the optimal arrival rate

is the unique real root of the following polynomial in the interval

:

Special case (symmetric system): If the service rates are equal (

), the condition simplifies to

, yielding the closed-form solution:

This analytical result allows for precise system tuning without an exhaustive numerical search.

7. Case Study

Consider a two-hop wireless network based on DECT-2020, as shown in

Figure 4. We analyze the network performance by focusing on the update process of a Portable Termination (PT) device. The PT generates updates according to a Poisson process and packs them into Transport Blocks (TBs) for transmission to a Fixed Termination (FT), with the transmission time following an exponential distribution. The FT receives the TBs and queues them for subsequent transmission to the sink, which also entails an exponentially distributed amount of time.

According to the ETSI standard [

21], 60 TBs can be transmitted within a frame consisting of 12 time slots. Assuming that there are six homogeneous PTs associated with the FT, the mean transmission speed is 10 TBs per frame. Assuming the sink has two directly connected FT devices receiving data from 6 PT devices, the average transmission rate on the second hop is 5 TBs per frame. Therefore, we model the DECT-2020 network as an exponential tandem queueing system with

and

.

These rates are derived from the standard’s frame capacity. With a maximum of 60 Transport Blocks (TBs) per frame:

Hop 1 (PT to FT): Six PTs share the channel. Assuming fair resource division, the service rate is updates/frame.

Hop 2 (FT to Sink): The sink supports multiple streams. The reduced rate updates/frame reflects the effective throughput after accounting for backhaul contention at the concentration point.

The numerical validation was performed using a custom discrete-event simulation (DES). For each data point, the system was simulated for a horizon of

T = 400,000 frames. A warm-up period of 1000 frames was discarded to remove transient initial conditions. The simulation parameters are summarized in

Table 3.

To validate the analytical expressions, we conducted simulations in which the arrival rate

was systematically varied to examine its influence on the system’s performance. The first and second moments of PAoI obtained from (

30) and (

31), respectively, are illustrated by solid red lines in

Figure 5 along with blue circles representing the first and second moment of PAoI obtained from simulations. For each

value used in simulations, we collect an empirical distribution of the PAoI and demonstrate a percentile-based interval for this distribution using vertical blue lines, so that 95% of the obtained PAoI values are within the bounds of the vertical line. The analytical model accurately captures the behavior of the system. In particular, the mean PAoI is estimated with a mean relative error of less than 1% and a maximum relative error of less than 5%. This agreement validates the theoretical framework and highlights its robustness in predicting PAoI under various load conditions.

As we mentioned earlier, the mean values without information about the deviation allow for limited analysis. For example, we consider a “three-sigma interval” from

to

in

Figure 6, using (

30) and (

33). This interval serves as a metric for PAoI variability, covering approximately 99.7% of the probability mass if the distribution were normal, and provides a heuristic bound for the tail behavior.

To extend our analysis beyond the exponential assumption and formally validate the impact of service time variability, we conducted a rigorous statistical comparison. We simulated systems where service times follow Erlang and hyperexponential distributions alongside the baseline Exponential case, calculating the mean and standard deviation of the PAoI. For each configuration, we collected independent batch means, where each batch consisted of 10,000 updates after a warm-up period of 500 updates.

An Erlang-distributed service time () implies that each update in each phase undergoes five sequential processing stages with exponentially distributed durations. For the first phase, the individual stage rate is set to 50, and for the second phase, it is set to 25, preserving the aggregate mean service rates of and . Technically, the Erlang distribution explicitly models the cumulative delay of multiple processing steps, such as wireless transmission, acknowledgment, digital-to-analog conversion, header addition, and data processing.

Conversely, the hyperexponential service time models a system with high variability. We assume that each update, with probability , is processed at one of two distinct rates. In the first phase, these rates are 30 and 6; in the second phase, they are 15 and 6. From a DECT-2020 perspective, this distribution captures the stochastic nature of updates with different TB lengths or varying numbers of retransmissions required due to channel conditions.

We denote the mean PAoI for the systems with Erlang, hyperexponential, and exponential service times by , , and , respectively. Similarly, , , and denote their standard deviations. While all three distributions share the same mean service time, they possess distinct coefficients of variation ( for Erlang, for Exponential, and for Hyperexponential).

First, we assessed the normality of the sample means using Q-Q plots.

Figure 7 presents the Quantile–Quantile (Q-Q) plots for the sample means under low (

), medium (

), and high (

) load conditions. While the distribution of means approximates normality in most regimes, deviations were observed at high loads due to the heavy-tailed nature of queueing delays near saturation. To ensure robustness, we employed two distinct statistical tests:

The results are summarized in

Table 4. At low loads (

), the

p-values are high (>0.05), indicating no significant difference. This is physically expected, as queueing is negligible in this regime, and the PAoI is dominated by the mean service time, which is identical across all distributions. However, as the load increases (

), both tests consistently yield

p-values well below the

threshold (with only exception of the Erlang distribution for

, where the difference is also statictically insignificant), often reaching values as low as

. This confirms that the service time variance has a statistically significant impact on information freshness whenever queueing dynamics are present.

To optimize the information freshness, we formulate the minimization problem for the mean PAoI with respect to the arrival rate

:

where

is given by Equation (

30).

Figure 8 illustrates the optimal arrival rate

obtained by solving the polynomial Equation (

40) for varying bottleneck capacities

. As predicted by the analytical derivation,

increases non-linearly with

, allowing the system to support higher update frequencies and lower PAoI as the service capacity improves.

8. Discussion

This study provides a framework for the analysis of PAoI in a two-phase exponential queueing system that represents the DECT-2020 network segment. The key idea for the analysis is to divide updates into four mutually exclusive groups based on the system states they observe upon arrival to the corresponding queue: (1) both servers are busy, (2) the first server is busy, and the second is idle, (3) the first server is idle, and the second is busy, and (4) both servers are idle. Once the updates have been divided, and the probability of belonging to each group has been identified, the LST of the PAoI is calculated for each group of packets. Then, by grouping the PAoI of different updates according to the law of total probability, an LST for the complete PAoI is obtained. This result allows us to estimate not only the mean values but also the variance and full distribution of the metric. The closed-form expressions accurately describe the system behavior under various configurations, and the analytical results demonstrate close alignment with simulations, showing a relative error of less than 1%. Furthermore, the analysis highlights the impact of the service time coefficient of variation. The hyperexponential distribution, having a higher coefficient of variation than the exponential distribution, leads to a higher mean PAoI. Conversely, the Erlang distribution results in a lower mean PAoI due to its lower coefficient of variation.

This study has limitations. First, the assumption of infinite queue capacity ignores packet drops, which are critical in high-load scenarios. Second, while the exponential approximation allows for analytical tractability, it may overestimate the tail latency compared to the deterministic components of TDMA slots.

Future work will focus on the following: (1) extending the analytical framework to general tandem networks to model deterministic service times more accurately; (2) analyzing the impact of finite buffer sizes on PAoI.